Abstract

We determined the acute effects of oxidative stress on glucose uptake and intracellular signaling in skeletal muscle by incubating muscles with reactive oxygen species (ROS). Xanthine oxidase (XO) is a superoxide-generating enzyme that increases ROS. Exposure of isolated rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles to Hx/XO (Hx/XO) for 20 min resulted in a dose-dependent increase in glucose uptake. To determine whether the mechanism leading to Hx/XO-stimulated glucose uptake is associated with the production of H2O2, EDL muscles from rats were preincubated with the H2O2 scavenger catalase or the superoxide scavenger superoxide dismutase (SOD) prior to incubation with Hx/XO. Catalase treatment, but not SOD, completely inhibited the increase in Hx/XO-stimulated 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake, suggesting that H2O2 is an intermediary leading to Hx/XO-stimulated glucose uptake with incubation. Direct H2O2 also resulted in a dose-dependent increase in 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles, and the maximal increase was threefold over basal levels at a concentration of 600 μmol/l H2O2. H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake was completely inhibited by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin, but not the nitric oxide inhibitor NG-monomethyl-L-arginine. H2O2 stimulated the phosphorylation of Akt Ser473 (7-fold) and Thr308 (2-fold) in isolated EDL muscles. H2O2 at 600 μmol/l had no effect on ATP concentrations and did not increase the activities of either the α1 or α2 catalytic isoforms of AMP-activated protein kinase. These results demonstrate that acute exposure of muscle to ROS is a potent stimulator of skeletal muscle glucose uptake and that this occurs through a PI3K-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: hydrogen peroxide, Akt phosphorylation, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

DISRUPTION OF THE GLUCOSE TRANSPORT SYSTEM in skeletal muscle can lead to alterations in glucose homeostasis (19). Although for many years it has been known that there are numerous physiological and pharmacological perturbations that can increase glucose transport in skeletal muscle, the signaling mechanisms that lead to transport activation are still poorly defined. What is well established is that there is more than one signaling cascade of intracellular proteins that mediate glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Insulin signaling to glucose transport is the best understood, as a variety of approaches, including studies using the inhibitor compounds wortmannin and LY-294002, have demonstrated that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) is necessary for insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle (23, 33, 36, 56). Physical exercise, the other major physiological stimulator of muscle glucose transport is not as well defined. Studies using isolated muscles contracted in vitro, a model of exercise, have shown that contraction-stimulated glucose transport is wortmannin insensitive and additive with insulin (23, 33). Muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout mice (55) and Akt2 knockout mice (49) have normal exercise-stimulated glucose transport, and, taken together, these studies suggest that exercise signaling to glucose transport is PI3K independent and distinct from insulin signaling.

There are many other stimuli that can increase glucose transport in skeletal muscle, including, but not limited to, hypoxia (6, 23), hyperosmotic stress (18, 22), 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribonucleoside (AICAR) (23, 42), metformin (57), leptin (3), bradykinin (30), the nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (14, 25), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (7, 53). Many of these stimuli are widely believed to utilize the same signaling network by which exercise increases glucose transport, and in recent years this has been hypothesized to involve the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). However, it is now clear that AMPK may mediate some but not all of these insulin-independent stimuli, and there are likely to be several distinct or overlapping signaling pathways leading to glucose transport in skeletal muscle (1, 25, 28, 43–45). For example, we have shown that the nitric oxide donor SNP increases skeletal muscle glucose uptake through a mechanism that is distinct from both the insulin- and contraction-signaling pathways (25).

Oxidative stress occurs in a cellular system when the production of free radical moieties exceeds the antioxidant capacity of that system. To date, two biochemical pathways have been identified as potential sources of intracellular free radical generation in skeletal muscle. Mitochondria continually produce free radicals in response to conditions, such as exercise, that increase oxygen uptake, via a reaction involving complexes I and III of the respiratory chain (8). Another source for free radicals is generation by xanthine oxidase (XO) (41), a ubiquitously expressed enzyme that is present in skeletal muscle (24). XO produces free radicals in the presence of oxygen and hypoxanthine (Hx) or XO, ATP degradation products that can be generated during skeletal muscle contraction (24). H2O2 can be generated from this reaction, and H2O2 has been shown to increase glucose transport under some experimental conditions (7). Thus, although H2O2 may be an important positive regulator of glucose transport in skeletal muscle, little is known about the signaling mechanisms that may mediate this process.

In the current study, we determined the effects of acute exposure of skeletal muscle to pharmacological agents that produce ROS and then assessed potential signaling mechanisms that might mediate the effects of these agents on glucose transport. We first used exogenous Hx/XO exposure of isolated skeletal muscle, a model system that has been proposed to reproduce what occurs in vivo where XO has been found in the blood vessel walls. We found that Hx/XO resulted in a dose-dependent increase in 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake in isolated EDL muscles, likely due to the generation of H2O2 in vitro. Direct incubation of muscles with H2O2 also resulted in dose-dependent increase in glucose transport, which occurred via an AMPK-independent, but PI3K-dependent signaling mechanism. Thus, ROS can positively mediate glucose transport in skeletal muscle.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing ~40 g were purchased from Kyudo (Tosu, Japan) and Taconic Farms (Germantown, MA). Animals were housed in an animal room maintained at 23°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and fed standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum. All protocols for animal use and euthanasia were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Saga Medical School and the Joslin Diabetes Center.

Materials

XO, H2O2, wortmannin, catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), D-glucose, and pyruvic acid were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Hx was purchased from Wako Chemical (Osaka, Japan). NG-nitro-L-arginine monomethyl ester (L-NMMA) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). 2-Deoxy-D-[1,2-3H]glucose and D-[14C]mannitol were purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA).

Muscle incubations

Rats were fed ad libitum until 8:00 AM on the day of the experiment, and the experiment commenced at 1:00 PM. Animals were killed by decapitation, and the EDL muscles were rapidly dissected. Both ends of each muscle were tied with suture (4–0 silk) and mounted on an incubation apparatus. The muscles were preincubated in 5 ml of Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (KRB; 117 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, and 24.6 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.5) containing 2 mmol/l pyruvate at 37°C for 30 min in the presence or absence of insulin (50 mU/ml) or AICAR (2 mM), and then incubated in the presence or absence of XO (0.2–200 mU/ml) with Hx (1 mmol/l) or H2O2 (0.03–24 mmol/l) at 37°C for 20 min. When added, the inhibitors catalase (3,000 mU/ml), SOD (300 U/ml), wortmannin (100 nmol/l), or L-NMMA (100 nmol/l) were present throughout the entire incubation and present at least 30 min prior to stimulation. The buffers were continuously gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2. Muscles were then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and used for the measurement of 2-DG uptake or analyzed for muscle enzymes and metabolites. For the measurement of H2O2 in the incubation buffer in the presence or absence of XO with Hx, the BIOXYTECH H2O2-560 assay was used (Portland, OR).

2-DG uptake

2-DG uptake was measured in 2 ml of KRB containing 1 mmol/l 2-deoxy-D-[1,2-3H]glucose (1.5 μCi/ml) and 7 mmol/l D-[14C]mannitol (0.45 μCi/ml) at 30°C for 10 min. Muscles were processed, radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting for dual labels, and 2-DG uptake was calculated as previously described (5). Isolated EDL muscles from rat were used for the current experiments. Mice were not used for these studies because the effects of H2O2 exposure on glucose uptake under our incubation conditions were not observed in mouse EDL muscles. The lack of stimulation by H2O2 is similar to other findings in our laboratory where stimuli that increase glucose uptake in the rat (e.g., metformin), have no effect in the mouse (N. Fujii and L. J. Goodyear, unpublished observation). We suspect this may be due to the much higher level of spontaneous activity of mice compared with rats or humans, activating the glucose transport system in the basal state.

Assays for muscle enzymes and metabolites

To measure ATP, ADP, and AMP concentrations, frozen muscles were weighed and then homogenized using a polytron (Kinematica, Switzerland) in trichloroacetic acid at −10°C, and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant of the homogenates was neutralized with 0.5 N tri-n-octylamine and then centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C. The supernatant was passed through a membrane filter with a 0.45 μm pore size and the sample was then analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (51).

For the measurement of isoform-specific AMPK activity, muscles were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (1:20 wt/vol) containing 20 mmol/l Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, 50 mmol/l NaCl, 250 mmol/l sucrose, 50 mmol/l NaF, 5 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mmol/l DTT, 4 mg/l leupeptin, 50 mg/l trypsin inhibitor, 0.1 mmol/l benzamidine and 0.5 mmol/l PMSF and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants (200 μg protein) were immunoprecipitated with isoform-specific antibodies to the α1 or α2 catalytic subunits of AMPK and protein A/G beads. These are anti-peptide antibodies made to the amino acid sequences DFYLATSPPDSFLDDHHLTR (339–358) of α1 and MDDSAMHIPPGLKPH (352–366) of α2 and protein A/G beads. Immnoprecipitates were washed twice in lysis buffer and twice in wash buffer (240 mmol/l HEPES and 480 mmol/l NaCl). Kinase reactions were performed in 40 mmol/l HEPES (pH 7.0), 0.2 mmol/l SAMS peptide (synthetic substrate for AMPK), 0.2 mmol/l AMP, 80 mmol/l NaCl, 0.8 mmol/l DTT, 5 mmol/l MgCl2, and 0.2 mmol/l ATP (2 μCi [γ-32P]ATP) in a final volume of 40 μl for 20 min at 30°C (13). At the end of the reaction, a 20-μl aliquot was removed and spotted on Whatman P81 paper. The papers were washed six times in 1% phosphoric acid and once with acetone. 32P incorporation was quantitated with a scintillation counter, and kinase activity was expressed as fold increases compared with basal samples.

Immunoblotting for AMPK Thr172 phosphorylation

Equal amounts of muscle lysates (40 μg protein) prepared as described above were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and blocked in TBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with phospho-AMPK (Thr172) antibody (Upstate Biotechnology). Bound primary antibodies were detected with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin-horseradish-peroxidase-linked whole antibody. The membranes were washed with TBS-T and then incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and exposed to film. Bands were visualized and quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunoblotting for Akt Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation

Pulverized muscle was homogenized with a Polytron in an ice-cold buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na3PO4, 100 mMNaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10 μM leupeptin, 3 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Homogenates were rotated end over end for 1 h at 4°C and then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

Akt Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation was assessed by immunoblotting. An equal amount of muscle protein (80 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and blocked in TBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with an antibody specific for Akt phosphorylated on Ser473 (1:1,000 dilution) or specific for Akt phosphorylated on Thr308 (1:2,000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000) in TBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature, and antibody binding was visualized as described above.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. For comparison of two means, an unpaired Student's t-test was performed. The effect of H2O2 on insulin or AICAR-stimulated 2-DG uptake was compared by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's protected least significant difference-test.

RESULTS

Effects of Hx/XO on glucose uptake in isolated EDL muscles

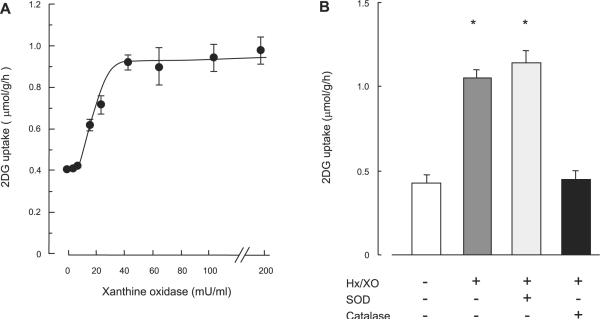

To determine whether ROS stimulates muscle glucose uptake, isolated EDL muscles were first incubated in buffer containing Hx in the presence of XO (Hx/XO). Incubation of EDL muscles with Hx/XO for 20 min resulted in a dose-dependent increase in 2-DG uptake (Fig. 1A). The maximal increase was 2.4-fold over basal levels at a concentration of 40 mU/ml XO in the presence of 1 mM Hx and did not increase further with 200 mU/ml XO. XO or Hx alone did not affect 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscle (data not shown), suggesting that reaction product(s) that appears in response to exposure of the combination of Hx and XO leads to increased muscle glucose uptake.

Fig. 1.

Hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase (Hx/XO)-stimulated 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake (A) and effects of catalase or superoxide dismutase (SOD) on Hx/XO-stimulated 2-DG uptake (B) in isolated extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. A: isolated EDL muscles were stimulated in the absence or presence of 0.2–200 mU/ml XO with 1 mM Hx for 20 min followed by measurement of 2-DG uptake, as described in RESEARCH AND METHODS; n = 5–7 per group. B: isolated EDL muscles were preincubated in KRB buffer containing 3,000 U/ml catalase or 300 U/ml SOD for 30 min and then stimulated in 40 mU/ml XO with 1 mM Hx for 20 min followed by the measurement of 2-DG uptake. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. basal condition.

Hx/XO stimulates glucose uptake through production of H2O2 in isolated EDL muscles

The combination of Hx and XO produces H2O2 and superoxide anions. To determine whether this occurs in our system, we measured H2O2 concentration in the incubation buffer containing XO and Hx and observed a significant increase (basal buffer: 0.9 ± 0.2, Hx/XO buffer; 9.1 ± 0.9 μmol/l). We next determined whether the increase in H2O2 and/or superoxide anions was responsible for the increase in glucose uptake by preincubation with the H2O2 scavenger catalase or the ROS scavenger SOD prior to incubation with Hx/XO. Figure 1B shows that catalase treatment, but not SOD, completely inhibited the increase in Hx/XO-stimulated glucose uptake, suggesting that H2O2 production leads to Hx/XO-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.

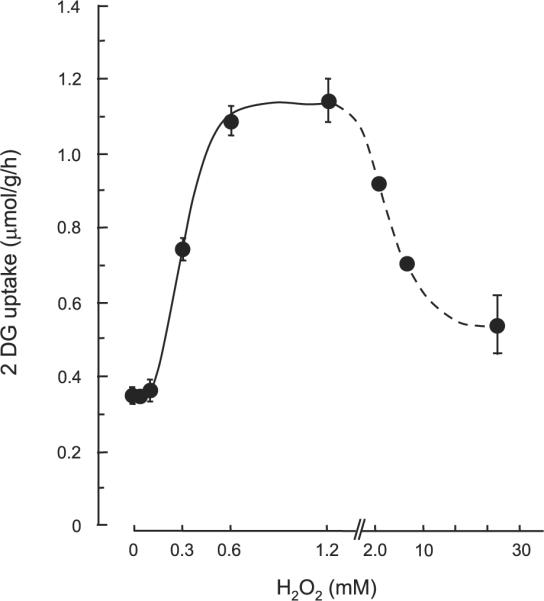

We next determined the effects of direct H2O2 incubation on skeletal muscle glucose uptake. H2O2 exposure for 20 min resulted in a dose-dependent increase in 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles (Fig. 2). The maximal increase was threefold over basal levels at H2O2 concentrations of 600 μmol/l and 1,200 μmol/l. With concentrations greater than 2.0 mmol/l there was a reduction in glucose uptake, and by 24 mmol/l H2O2 glucose uptake was at basal levels. These findings suggest that there is an optimal concentration of H2O2 for the stimulation of glucose uptake and that at higher concentrations H2O2 is either ineffective or inhibitory.

Fig. 2.

Effects of H2O2 (0.1–24 mM) on 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles. Isolated EDL muscles were stimulated in the absence or presence of 0.1–24 mM H2O2 for 20 min followed by the measurement of 2-DG uptake, as described in RESEARCH AND METHODS. Data are means ± SE; n = 5–7 per group.

In the present experiments, we added H2O2 to the incubation buffer immediately before the stimulation period. When we measured the H2O2 level in the buffer following 20 min of stimulation, the level (0.7 ± 0.2 μmol/l) was similar to that of the control buffer (0.9 ± 0.2 μmol/l), meaning that the incubated muscles were exposed to rapidly decreasing H2O2 levels over the course of the 20-min incubation period. We speculate that the degradation rate of H2O2 may be high under our incubation conditions containing isolated EDL muscles. The Hx/XO system is continuously generating H2O2 and achieving a steady state, while the added H2O2 is being rapidly degraded.

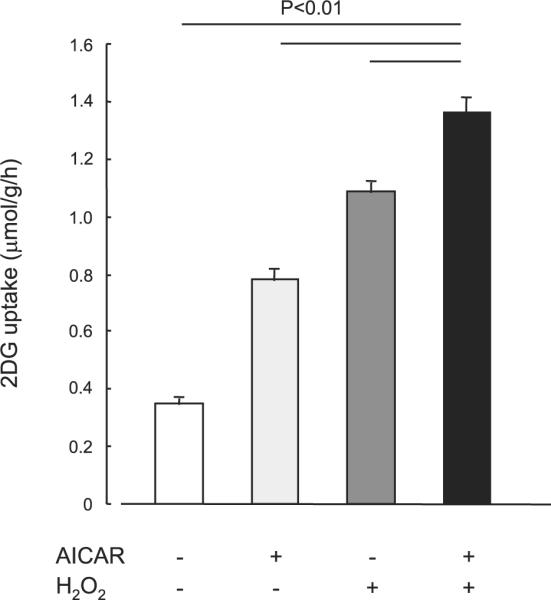

Effects of H2O2 on AICAR-stimulated glucose uptake and AMPK activity

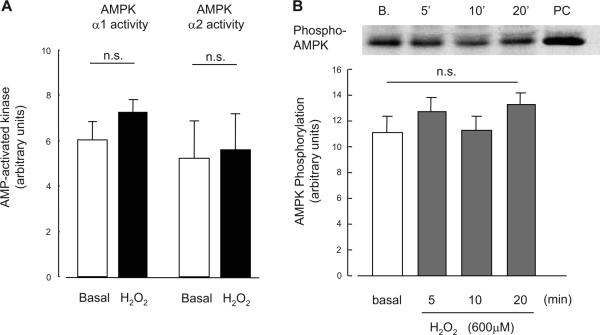

There are multiple mechanisms that increase glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, and in recent years AMPK has been suggested to be a key signaling protein regulating insulin-independent glucose uptake. To address the hypothesis that H2O2 stimulates glucose uptake through activation of AMPK, we carried out several experiments assessing glucose uptake and AMPK activity. First, we determined whether the combination of a maximally stimulating dose of H2O2 plus maximal AICAR had additive effects on glucose uptake. Isolated EDL muscles were incubated in KRB buffer in the absence or presence of 2 mmol/l AICAR for 50 min. H2O2 (600 μmol/l) was added during last 20 min of the 50-min incubation period. The combination of H2O2 plus AICAR had partially additive effects on skeletal muscle glucose uptake (Fig. 3), suggesting different mechanisms for H2O2- and AICAR-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. There was also a partially additive effect of the combination Hx/XO plus AICAR on skeletal muscle glucose uptake (data not shown). Consistent with this finding, incubation of isolated EDL muscles with H2O2 (600 μmol/l) for a total of 50 min had no effect on either AMPKα1 or AMPKα2 activities assessed using an immune complex assay (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylation of AMPK on Thr172, a key regulatory site for AMPK activity, was also unchanged with H2O2 incubation for 5, 10, or 20 min (Fig. 4B). H2O2 incubation did not enhance AICAR-stimulated AMPK phosphorylation (data not shown). Finally, H2O2 had no effect on the muscle metabolites ATP, ADP, and AMP (Table 1). Collectively, these data suggest that AMPK is not involved as an intermediary in the signaling cascade leading to H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.

Fig. 3.

Effects of H2O2 on 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribonucleoside (AICAR)-stimulated 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles. Isolated EDL muscles were incubated in KRB buffer in the absence or presence of 2 mmol/l AICAR for 50 min. H2O2 incubation was at a concentration (600 μmol/l) that elicited maximal increase in glucose uptake, as indicated in Fig. 2, and was added during the last 20 min the of 50-min incubation period. Data are means ± SE; n = 6–8 per group.

Fig. 4.

Effects of H2O2 on AMPKα1 and -α2 activity (A) and effects of H2O2 on phosphorylation level of AMPKα (Thr172)(B) in isolated EDL muscles. Isolated EDL muscles were incubated in KRB buffer in the presence of H2O2 at a concentration (600 μmol/l) that elicited maximal increase in glucose uptake, as indicated in Fig. 2. Data are means ± SE; n = 6 per group.

Table 1.

Effect of H2O2 on ATP, ADP, and AMP concentrations and the AMP/ATP ratio in isolated EDL muscles

| ATP | ADP | AMP | AMP/ATP Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.5±0.2 | 0.80±0.02 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.011±0.002 |

| H2O2 | 5.5±0.1 | 0.83±0.02 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.017±0.005 |

Data for concentrations are means ± SE in μmol/g wet wt; n = 5 per group.

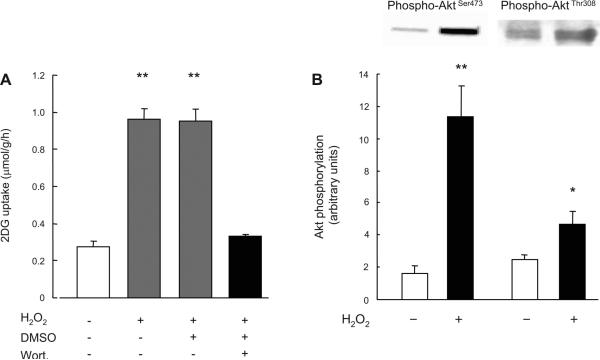

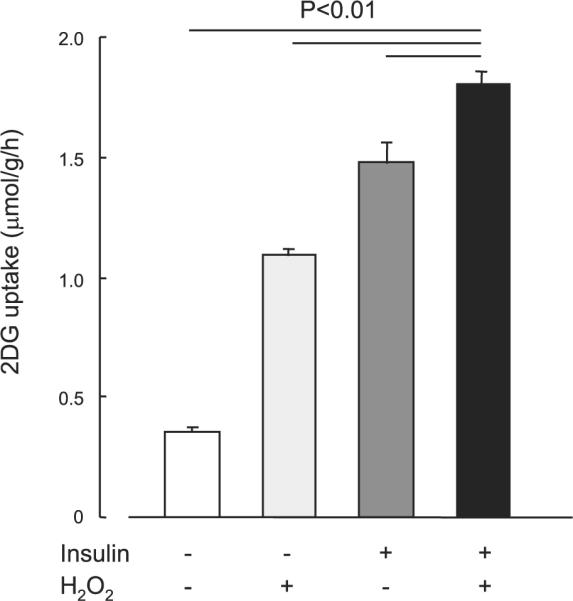

H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake is wortmannin sensitive

We next determined whether the mechanism leading to H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake involved similar signaling molecules as insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Isolated EDL muscles were incubated in the absence or presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (100 nmol/l) for 30 min and then incubated with H2O2 (600 μmol/l) for 20 min. Wortmannin treatment completely inhibited the increase in H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake (Fig. 5A), suggesting that H2O2 stimulates glucose uptake through a PI3K-dependent pathway. We further determined whether H2O2 stimulates Akt phosphorylation, which is a downstream target of PI3K. As shown in Fig. 5B, H2O2 stimulated Akt Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation sevenfold and about twofold, respectively. If H2O2 and insulin stimulate glucose uptake through the same mechanism, then the combination of H2O2 plus insulin should not be additive. However, we were surprised to find that the combination of maximal H2O2 plus maximal insulin had partially additive effects on skeletal muscle glucose uptake (Fig. 6). This partially additive effect on skeletal muscle glucose uptake was also observed with the combination of Hx/XO plus maximal insulin (data not shown). This finding suggests that H2O2 and insulin signaling to glucose uptake are at least partially divergent and that H2O2 signaling involves an insulin-independent as well as a PI3K-dependent protein.

Fig. 5.

Effects of wortmannin on H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake (A) and effects of H2O2 on Akt Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation (B) in isolated EDL muscles. A: isolated EDL muscles were preincubated in KRB buffer in the presence or absence wortmannin (100 nM) followed by treatment with H2O2 at a concentration (600 μmol/l) that elicited maximal increase in H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake, as indicated in Fig. 2. Since wortmannin was dissolved in DMSO, which may act as a scavenger of superoxide anion, 2-DG uptake was measured in the presence of 0.2% DMSO for another control; n = 5–6 per group. B: isolated EDL muscles were incubated in KRB buffer in the presence or absence of H2O2 (600 μmol/l); n = 6 per group. Data are means ± SE. **P < 0.01 vs. control.

Fig. 6.

Effects of H2O2 on insulin-stimulated 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles. Isolated EDL muscles were preincubated in KRB buffer in the presence or absence of insulin at a concentration (300 nM) that induced maximal increase in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. H2O2 incubation was at a concentration (600 μmol/l) that elicited maximal increase in glucose uptake, as indicated in Fig. 2, and was added during last 20 min of the 50-min incubation period. Data are means ± SE; n = 7–8 per group.

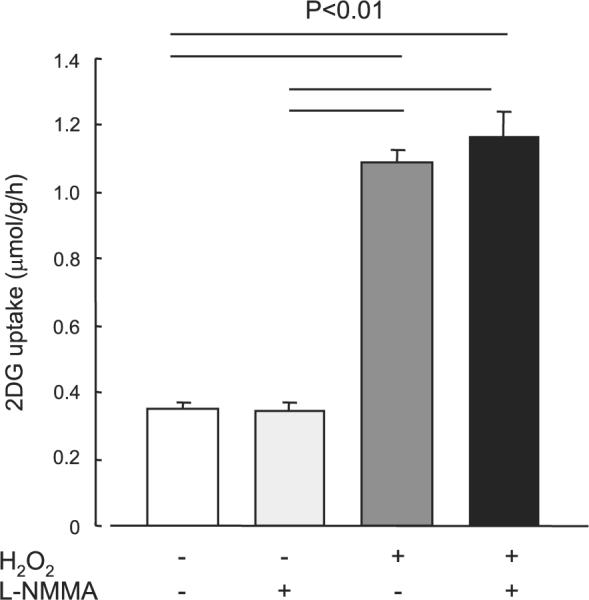

Nitric oxide synthase inhibition does not affect H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake

We (25) have previously demonstrated that wortmannin partially decreases glucose uptake stimulated by the nitric oxide donor SNP. To determine whether H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake is similar to, or distinct from, nitric oxide-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, isolated EDL muscles were incubated in the absence or presence of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NMMA (100 nmol/l) for 30 min and then incubated with H2O2 (600 μmol/l) for 20 min. L-NMMA had no effect on H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake (Fig. 7), suggesting different mechanisms for H2O2- and nitric oxide-stimulated glucose uptake.

Fig. 7.

Effects of NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA) on H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles. Isolated EDL muscles were preincubated in KRB buffer in the presence or absence of L-NMMA (100 nmol/l) for 30 min, followed with treatment with H2O2 at a concentration (600 μmol/l) that induces maximal increase in H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake, as indicated in Fig. 2. Data are means ± SE; n = 5–6 per group.

DISCUSSION

Skeletal muscles are continuously exposed to oxidative stress, and it is well established that a number of different enzymes involved in skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism are regulated by the redox state of the cell (10). Physical exercise causes redox changes in various cells and tissues, and the ROS generated from the oxidation processes can regulate a variety of key molecular mechanisms that are linked with important cellular processes, such as immune function, cell proliferation, inflammation, and metabolism (52). Despite the importance of understanding how oxidative stress regulates glucose metabolism, previous reports have been inconclusive in determining the effects of oxidative stressors on glucose uptake. Incubation of L6 myotubes in Hx/XO in the absence of insulin for 1 h did not increase glucose uptake, whereas longer-term incubation for more than 8 h was effective in increasing rates of uptake (31, 32). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, an 18-h exposure to glucose oxidase, an H2O2 generating enzyme, was necessary to increase 2-DG uptake (48). These findings suggest that transcriptional regulation to increase glucose transporter proteins is necessary to increase glucose transport in L6 cells and 3T3-L1 adipocytes in response to oxidative stress (4). In contrast, the current study, as well as other previous reports, suggest that acute exposure to oxidative stress can increase glucose uptake. In M07 cells, a human leukemic megakaryocytic cell line, rapid enhancement of glucose transport occurred with a 20-min exposure to a low dose of H2O2, an effect lost at higher doses (16). This later study is consistent with our current findings, where an acute exposure of H2O2 increased glucose transport in isolated EDL muscles at doses up to 1.2 mM H2O2, but higher doses of H2O2 returned glucose transport to basal levels. H2O2 has also been reported to increase glucose transport in isolated epitrochlearis muscles with a 30-min exposure at 3.0 mM (7). Taken together, these studies suggest that there may be an optimal range of oxidative stress that results in enhancement of glucose transport. In relating this to a physiologically relevant system, it may be that the optimal level of H2O2 occurs in muscle during physical exercise, promoting glucose uptake, although this will need to be addressed experimentally in future studies.

Despite the finding nearly 15 years ago that H2O2 can stimulate glucose transport in isolated rat epitrochlearis muscles (7), in recent years there has been little focus on elucidating cell signaling mechanisms that may mediate the metabolic effects of oxidative stress. There are distinct signaling cascades that stimulate glucose transport in muscle, including insulin-dependent signaling, exercise or muscle contraction, AMPK, and nitric oxide-mediated signaling. In the present study, H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles was completely inhibited in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin. This finding is similar to that of another study that found that the treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with wortmannin completely blocks the subsequent activation of Akt phosphorylation in response to cell stimulation with exogenous H2O2 (38). Since wortmannin could theoretically act through nonspecific inhibition of a PI3K-independent signaling mechanism(11), we assessed Akt phosphorylation, a downstream kinase in PI3K signaling. Our findings that Akt Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation was significantly increased in muscle in the presence of H2O2 at a concentration that increased glucose transport, reinforces the concept that H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake involves PI3K-Akt signaling in skeletal muscles.

The mechanism by which H2O2 increases Akt phosphorylation in our system is not clear. One possibility is that protein tyrosine phosphates (PTPases) are inactivated in our system, as has been shown in other cell types (2, 37, 39). PTP1B, in particular, is considered to be a major candidate for the negative regulation of insulin action, functioning to decrease insulin receptor and IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation. Although we cannot rule out a role for PTPB1 in H2O2-stimulated PI3K/Akt signaling because we did not measure phosphatase activity, we think this is unlikely, because we did not observe any effect of H2O2 on IRS-1 Tyr612 phosphorylation (data not shown). Thus, the mechanism by which H2O2 increases PI3K/Akt signaling will be an interesting area for future investigation.

Exogenous oxidants such as H2O2 have been known to be capable of directly activating the insulin receptor and consequently downstream signaling targets in liver (20) and adipocytes (12, 29, 35). However, the effects of oxidative stress on insulin-stimulated glucose transport and signaling have been inconsistent, raising questions as to whether oxidative stress is a positive or negative regulator of insulin signaling and glucose transport. The effect of H2O2 on insulin signaling is complex and could be dependent on the sequence in which cells or tissues are exposed to H2O2 or insulin. If administered prior to insulin, micromolar concentrations of H2O2 exposure to cultured cells can inhibit insulin action (4, 21, 27). In L6 muscle cells, insulin-stimulated glucose transport was suppressed when muscle cells were incubated with insulin and H2O2 (4) or with insulin following the prior stimulation of H2O2-producing glucose oxidase (27), suggesting that H2O2 is likely to down-regulate insulin signaling. Consistent with this hypothesis, in NIH-B cells, H2O2 potently inhibited insulin signaling and resulted in the development of insulin resistance (21). On the other hand, mice overexpressing glutathione peroxidase-1, an intracellular selenoprotein that reduces H2O2, developed insulin resistance (40), suggesting that H2O2 is a positive mediator of insulin action. If H2O2 is given on its own or following insulin, it can be an insulin mimetic or partly additive to insulin (7), and in the current study, we found that H2O2 stimulates glucose transport in isolated muscles and that the combination with insulin and H2O2 had partially additive effects on muscle glucose transport. These results suggest that H2O2 does not impair maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport and that skeletal muscle plays a role in glucose handling in response to H2O2 stimulation.

A recent study showed that ROS have a causal role in different forms of insulin resistance (26). In vivo, this becomes even more complex when physical exercise, stress, disease state, and circulating systemic factors are all interacting. The incidence of insulin resistance and diabetes is inversely correlated with tissue antioxidant enzyme activities and blood antioxidant concentrations (15, 17, 54). In contrast, exercise generates nitric oxide and ROS and has a key role in the prevention of diabetes and improved insulin action in skeletal muscle. One explanation of these conflicting results is that excessive and/or chronic oxidative stress would induce insulin resistance in various cell types, whereas optimal and acute oxidative stress can have positive effects on glucose transport. In future studies, it will be important to determine the different mechanisms by which acute exposure of oxidative stress caused by exercise and chronic exposure of oxidative stress caused by hyperglycemia alters glucose homeostasis.

Nitric oxide and ROS exert complex effects on muscle contraction, metabolism, and gene expression (47). We previously reported that SNP, a nitric oxide donor, enhances glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and is associated with activation of the α1 catalytic subunit of AMPK (25). AMPK is a key regulatory enzyme in the control of cell-energy homoeostasis, acting as a “fuel gauge” and functioning to increase ATP generation under conditions of increased energy expenditure (22, 46). Recent studies report increased AMPK activity in response to oxidative stress in NIH-3T3 cells (9) and in isolated rat epitrochlearis (53) and EDL muscles (50). AMPKα1 activity increased in a time- and dose-dependent manner in H2O2-stimulated epitrochlearis muscles, whereas AMPKα2 activity was unaffected (53). The activation of AMPKα1 was blocked in the presence of the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), whereas NAC only partially (~50%) decreased H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake (53). Sandstrom et al. (50) also showed that NAC reduced contraction-stimulated glucose uptake as well as AMPK activity and phosphorylation in EDL by ~50%, but NAC did not alter insulin-, hypoxia-, or AICAR-stimulated glucose uptake. These findings suggest that endogenous H2O2 production may play an important role in contraction-stimulated glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle that may partially be mediated by AMPK activation. In contrast to these studies, we found no effect of H2O2 on either AMPKα1 or -α2 activities in isolated EDL muscles. Furthermore, we show no effect of H2O2 on AMPK Thr172 phosphorylation.

The lack of AMPK activation with H2O2 is also consistent with our data showing that H2O2 did not significantly alter ATP concentrations and the AMP/ATP ratio in the incubated muscles. A recent study demonstrated that addition of pyruvate to the perfusate prevented the H2O2-mediated reduction in cardiac mechanical dysfunction, activation of myocardial AMPK activity, increase in AMPK phosphorylation, and the increase in the Cr/PCr ratio (34). This may suggest that an effect of H2O2 on lowering energy levels in heart muscle was prevented by addition of pyruvate to the buffer. When we measured the dose response curve for H2O2-stimulated 2-DG uptake in isolated EDL muscles, we observed that higher doses (>2 mM) of H2O2 induced a dose-dependent decrease in 2-DG uptake and an increase in muscle stiffness. Since the dose (0.6 mM) of H2O2 in our experiment was much lower than that in previous studies (3 mM) (50, 53), the control of cell-energy homoeostasis might have been better regulated in our muscles. Therefore, the difference compared with previous studies in terms of AMPK activity and ATP levels in H2O2-stimulated muscles may be due to a different dose of H2O2. Our finding that the combination of H2O2 plus AICAR had additive effects on skeletal muscle glucose uptake suggests that the H2O2 doses of 0.6 mM do not stimulate glucose transport through an AMPK-dependent mechanism. Our finding that the NOS inhibitor L-NMMA had no effect on H2O2-stimulated glucose uptake in isolated skeletal muscles demonstrates that the nitric oxide signaling mechanism is also not functioning to increase glucose transport with H2O2.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that Hx/XO-stimulated glucose uptake in isolated EDL muscles is associated with the production of H2O2 and that H2O2 stimulates muscle glucose transport. The mechanism by which H2O2 increases glucose uptake does not involve AMPK or nitric oxide signaling. Instead, PI3K is necessary for H2O2-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Interestingly, this signaling mechanism is likely to be only partially overlapping with insulin signaling to glucose uptake. In contrast to the hypothesis that there are two signaling pathways to glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, it is now apparent that there are multiple mechanisms, some distinct and some overlapping. Elucidating these pathways will be important for understanding optimal treatments for muscle in insulin resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by KAKENHI 13780027 and 16500412 (Y. Higaki), Saga Medical School Grants (Y. Higaki), and National Institutes of Health Grants AR-45670 and AR-42238 (L. J. Goodyear).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes BR, Ryder JW, Steiler TL, Fryer LG, Carling D, Zierath JR. Isoform-specific regulation of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle from obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats in response to contraction. Diabetes. 2002;51:2703–2708. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett WC, DeGnore JP, Keng YF, Zhang ZY, Yim MB, Chock PB. Roles of superoxide radical anion in signal transduction mediated by reversible regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34543–34546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berti L, Gammeltoft S. Leptin stimulates glucose uptake in C2C12 muscle cells by activation of ERK2. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;157:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair AS, Hajduch E, Litherland GJ, Hundal HS. Regulation of glucose transport and glycogen synthesis in L6 muscle cells during oxidative stress. Evidence for cross-talk between the insulin and SAPK2/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36293–36299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruning JC, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Hayashi T, Horsch D, Accili D, Goodyear LJ, Kahn CR. A Muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout challenges the current concepts of glucose disposal and NIDDM pathogenesis. Mol Cell. 1998;2:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartee GD, Douen AG, Ramlal T, Klip A, Holloszy JO. Stimulation of glucose transport in skeletal muscle by hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1593–1600. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartee GD, Holloszy JO. Exercise increases susceptibility of muscle glucose transport to activation by various stimuli. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1990;258:E390–E393. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.2.E390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SL, Kim SJ, Lee KT, Kim J, Mu J, Birnbaum MJ, Soo KS, Ha J. The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by H2O2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connett RJ, Sahlin K. Handbook of Physiology. Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Am. Physiol. Soc.; Bethesda, MD: 1996. Control of glycolysis and glycogen metabolism; pp. 870–911. sect. 12, part III, chapt. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross MJ, Stewart A, Hodgkin MN, Kerr DJ, Wakelam MJ. Wortmannin and its structural analogue demethoxyviridin inhibit stimulated phospholipase A2 activity in Swiss 3T3 cells. Wortmannin is not a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25352–25355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czech MP, Lawrence JC, Jr, Lynn WS. Evidence for the involvement of sulfhydryl oxidation in the regulation of fat cell hexose transport by insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4173–4177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies SP, Carling D, Hardie DG. Tissue distribution of the AMP-activated protein kinase, and lack of activation by cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase, studied using a specific and sensitive peptide assay. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:123–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etgen GJ, Jr, Fryburg DA, Gibbs EM. Nitric oxide stimulates skeletal muscle glucose transport through a calcium/contraction- and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-independent pathway. Diabetes. 1997;46:1915–1919. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes. 2003;52:1–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorentini D, Hakim G, Bonsi L, Bagnara GP, Maraldi T, Landi L. Acute regulation of glucose transport in a human megakaryocytic cell line: difference between growth factors and H(2)O(2) Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:923–931. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Giles WH, Brown DW. The metabolic syndrome and antioxidant concentrations: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes. 2003;52:2346–2352. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsayeth J, Gould MK. Effects of hyperosmolarity on basal and insulin-stimulated muscle sugar transport. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1981;240:E263–E267. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.3.E263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodyear LJ, Kahn BB. Exercise, glucose transport, and insulin sensitivity. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:235–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.235. 235–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadari YR, Tzahar E, Nadiv O, Rothenberg P, Roberts CT, Jr, LeRoith D, Yarden Y, Zick Y. Insulin and insulinomimetic agents induce activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase upon its association with pp185 (IRS-1) in intact rat livers. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17483–17486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen LL, Ikeda Y, Olsen GS, Busch AK, Mosthaf L. Insulin signaling is inhibited by micromolar concentrations of H(2)O(2). Evidence for a role of H(2)O(2) in tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25078–25084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Fujii N, Habinowski SA, Witters LA, Goodyear LJ. Metabolic stress and altered glucose transport: activation of AMP-activated protein kinase as a unifying coupling mechanism. Diabetes. 2000;49:527–531. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Kurth EJ, Winder WW, Goodyear LJ. Evidence for 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase mediation of the effect of muscle contraction on glucose transport. Diabetes. 1998;47:1369–1373. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellsten Y, Frandsen U, Orthenblad N, Sjodin B, Richter EA. Xanthine oxidase in human skeletal muscle following eccentric exercise: a role in inflammation. J Physiol. 1997;498:239–248. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higaki Y, Hirshman MF, Fujii N, Goodyear LJ. Nitric oxide increases glucose uptake through a mechanism that is distinct from the insulin and contraction pathways in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2001;50:241–247. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.JeBailey L, Wanono O, Niu W, Roessler J, Rudich A, Klip A. Ceramide- and oxidant-induced insulin resistance involve loss of insulin-dependent Rac-activation and actin remodeling in muscle cells. Diabetes. 2007;56:394–403. doi: 10.2337/db06-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorgensen SB, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Frosig C, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Vaulont S, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF. Knockout of the alpha2 but not alpha1 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase isoform abolishes 5-amino-imidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranosidebut not contraction-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1070–1079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadota S, Fantus IG, Deragon G, Guyda HJ, Hersh B, Posner BI. Peroxide(s) of vanadium: a novel and potent insulin-mimetic agent which activates the insulin receptor kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;147:259–266. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishi K, Muromoto N, Nakaya Y, Miyata I, Hagi A, Hayashi H, Ebina Y. Bradykinin directly triggers GLUT4 translocation via an insulin-independent pathway. Diabetes. 1998;47:550–558. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozlovsky N, Rudich A, Potashnik R, Bashan N. Reactive oxygen species activate glucose transport in L6 myotubes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozlovsky N, Rudich A, Potashnik R, Ebina Y, Murakami T, Bashan N. Transcriptional activation of the Glut1 gene in response to oxidative stress in L6 myotubes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33367–33372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee AD, Hansen PA, Holloszy JO. Wortmannin inhibits insulin-stimulated but not contraction-stimulated glucose transport activity in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1995;361:51–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leon H, Atkinson LL, Sawicka J, Strynadka K, Lopaschuk GD, Schulz R. Pyruvate prevents cardiac dysfunction and AMP-activated protein kinase activation by hydrogen peroxide in isolated rat hearts. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82:409–416. doi: 10.1139/y04-050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludvigsen C, Jarett L. Similarities between insulin, hydrogen peroxide, concanavalin A, and anti-insulin receptor antibody stimulated glucose transport: increase in the number of transport sites. Metabolism. 1982;31:284–287. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund S, Holman GD, Schmitz O, Pedersen O. Contraction stimulates translocation of glucose transporter GLUT4 in skeletal muscle through a mechanism distinct from that of insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5817–5821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahadev K, Motoshima H, Wu X, Ruddy JM, Arnold RS, Cheng G, Lambeth JD, Goldstein BJ. The NAD(P)H oxidase homolog Nox4 modulates insulin-stimulated generation of H2O2 and plays an integral role in insulin signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1844–1854. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1844-1854.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahadev K, Wu X, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Lawrence JT, Goldstein BJ. Hydrogen peroxide generated during cellular insulin stimulation is integral to activation of the distal insulin signaling cascade in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48662–48669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahadev K, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Goldstein BJ. Insulin-stimulated hydrogen peroxide reversibly inhibits protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1b in vivo and enhances the early insulin action cascade. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21938–21942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClung JP, Roneker CA, Mu W, Lisk DJ, Langlais P, Liu F, Lei XG. Development of insulin resistance and obesity in mice overexpressing cellular glutathione peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8852–8857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308096101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCord JM, Fridovich I. The reduction of cytochrome c by milk xanthine oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5753–5760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merrill GF, Kurth EJ, Hardie DG, Winder WW. AICA riboside increases AMP-activated protein kinase, fatty acid oxidation, and glucose uptake in rat muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1997;273:E1107–E1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.6.E1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mu J, Brozinick JT, Jr, Valladares O, Bucan M, Birnbaum MJ. A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in contraction- and hypoxia-regulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Musi N, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase and muscle glucose uptake. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;178:337–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musi N, Hirshman MF, Nygren J, Svanfeldt M, Bavenholm P, Rooyackers O, Zhou G, Williamson JM, Ljunqvist O, Efendic S, Moller DE, Thorell A, Goodyear LJ. Metformin increases AMP-activated protein kinase activity in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2074–2081. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponticos M, Lu QL, Morgan JE, Hardie DG, Partridge TA, Carling D. Dual regulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase provides a novel mechanism for the control of creatine kinase in skeletal muscle. EMBO J. 1998;17:1688–1699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reid MB. Nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and skeletal muscle contraction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:371–376. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudich A, Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Hemi R, Kanety H, Bashan N. Prolonged oxidative stress impairs insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1562–1569. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakamoto K, Arnolds DE, Fujii N, Kramer HF, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Role of Akt2 in contraction-stimulated cell signaling and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E1031–E1037. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00204.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandstrom ME, Zhang SJ, Bruton J, Silva JP, Reid MB, Westerblad H, Katz A. Role of reactive oxygen species in contraction-mediated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2006;575:251–262. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seino T, Higaki Y, Koyama K, Ogasawara M. Continuous production of Hx in slow-twitch muscles contributes to exercise-induced prolonged hyperuricemia. Purine Pyrimidine Metab. 1998;22:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sen CK. Antioxidant and redox regulation of cellular signaling: introduction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:368–370. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toyoda T, Hayashi T, Miyamoto L, Yonemitsu S, Nakano M, Tanaka S, Ebihara K, Masuzaki H, Hosoda K, Inoue G, Otaka A, Sato K, Fushiki T, Nakao K. Possible involvement of the alpha1 isoform of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase in oxidative stress-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E166–E173. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00487.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vincent AM, Russell JW, Low P, Feldman EL. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:612–628. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wojtaszewski JF, Higaki Y, Hirshman MF, Michael MD, Dufresne SD, Kahn CR, Goodyear LJ. Exercise modulates postreceptor insulin signaling and glucose transport in muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1257–1264. doi: 10.1172/JCI7961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeh JI, Gulve EA, Rameh L, Birnbaum MJ. The effects of wortmannin on rat skeletal muscle. Dissociation of signaling pathways for insulin- and contraction-activated hexose transport. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2107–2111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, Musi N, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Moller DE. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]