Abstract

This study examined the relations among involvement in intimate partner psychological abuse, alcohol-related problems, and suicide proneness as measured by the Life Attitudes Schedule – Short Form (LAS-SF) in college women (N = 709). Results revealed that, as expected, being involved in a psychologically abusive relationship was significantly and positively correlated with alcohol-related problems and alcohol-related problems were significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness. Additionally, the intimate partner psychological abuse involvement-suicide proneness link was significantly mediated by alcohol-related problems. Implications are offered for the improved identification and treatment of young women at risk for suicidal and health-diminishing behaviors.

Keywords: Psychological abuse, Alcohol problems, Suicide, College women

Involvement in Intimate Partner Psychological Abuse and Suicide Proneness in College Women: Alcohol Related Problems as a Potential Mediator

Suicidal behavior and involvement in intimate partner abuse are two major public health concerns for women in the United States (American College Health Association, 2004; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Suicide is a leading cause of death for young women and women engage in many types of suicidal behaviors (ideation and attempts) more frequently than men (Baca-Garcia, Perez-Rodriguez, Mann, & Oquendo, 2008; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Friend, & Powell, in press; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Sanders, Crane, & Monson, 1998). Moreover, research has shown that approximately one third of college women have experienced physical partner abuse, as perpetrators and/or victims (Smith, Thompson, Tomaka, & Buchanan, 2005; Straus & Ramirez, 2007). Involvement in intimate partner psychological abuse is even more common as research indicates that as many as 75% of college women have reported being victims of intimate partner psychological abuse (Neufield, McNamera, & Ertl, 1999) while approximately 61% reported perpetrating psychological abuse towards an intimate partner (Fossos, Neighbors, Kaysen, & Hove, 2007). Given that dating violence has often been shown to be reciprocal in nature among college students (Follingstad, Bradley, Laughlin, & Burke, 1999; Gover, Kaukinen, & Fox, 2008, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2009), these similar prevalence rates are not surprising. Furthermore, psychological abuse has been identified as a risk factor for suicidal behaviors in women (e.g., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Snarr, Slep, & Heyman, 2009; Kaslow et al., 2000; Leiner, Compton, Houry, & Kaslow, 2008). College women are the focus of the present work as both suicidal behaviors and involvement in intimate partner abuse have been shown to be prevalent on university campuses (Straus, 2004; Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2004).

Research suggests that there is a strong positive association between involvement in partner abuse (either as a victim or perpetrator) and suicidal behaviors in women (e.g., Coker et al., 2000; Kernic, Wolf, & Holt, 2000). In a sample of African-American women, Kaslow and colleagues (2000) found that suicide attempters were 2.5 times more likely to report experiencing physical abuse and 2.8 times more likely to report experiencing psychological abuse than non-attempters. In keeping with these findings, Coker and associates (2002) found that women who had experienced psychological abuse were significantly more likely to have ever considered suicide or made a suicide attempt. Moreover, many women who physically or psychologically abuse their intimate partner also engage in suicidal behaviors (Kreiter et al., 1999). Although several studies have documented an association between partner abuse and suicide, not all women who are involved in abusive relationships engage in subsequent suicidal behaviors. Thus, it is important to further characterize this relationship by examining potential mechanisms through which involvement in partner abuse may lead to later suicidality.

Prior research has considered several possible mediating factors that may help delineate the partner abuse-suicide link. However, little research has investigated the association between involvement in intimate partner abuse and engagement in suicidal behaviors on university campuses, and no research to our knowledge has examined mediating variables for this relationship among college women. The previous research in this area has identified social support (Thompson, Kaslow, Short, & Wyckoff, 2002), PTSD (Thompson et al., 1999, Weaver et al., 2005), depression (Leiner et al., 2008), and substance use (Kaslow et al., 1998) as potential mediating factors for the partner abuse-suicidal behaviors relation among non-college women. Considering the substantial occurrence of alcohol use on college campuses (Sher & Rutledge, 2007), the mediating variable focused on in the current study is college women’s alcohol use and related problems.

Not only is excessive alcohol consumption relatively common on college campuses (Sher & Rutledge, 2007), researchers have substantiated that college students are a specific group who are at high risk for alcohol-related problems (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). College women, in particular, have shown a recent increase in heavy alcohol consumption (Wechsler et al., 2002). Young and colleagues (2005) found that 25% of women in their college student sample (N = 1,231) engaged in frequent binge drinking. Moreover, multiple studies (e.g., Anderson, 2002; Caetano, Cunradi, Schafer, & Clark, 2000; Caetano, Schafer, & Cunradi, 2001; Chase, O’Farrell, Murphy, Fals-Stewart, & Murphy, 2003; El-Bassel et al., 2003; Field & Caetano, 2004; Fossos et al., 2007; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004; Temple, Weston, Stuart, & Marshall, 2008; White & Chen, 2002) have demonstrated that women’s alcohol use and alcohol-related problems have a strong association with women’s experiences of both intimate partner abuse perpetration and victimization. For instance, DeKeseredy and Schwartz (1998) found that 61.9% of college women who were heavy drinkers compared to only 37.7% of light drinkers reported adult intimate partner victimization. To explain this relationship, Testa and Leonard (2001) suggest that alcohol may be used as a coping mechanism for the physical and emotional pain associated with being abused by an intimate partner. Similarly, Luthra and Gidycz (2006) reported that partner abuse perpetrators are five times more likely than non-perpetrators to use alcohol. Some researchers have suggested that women who are involved in psychologically abusive relationships may be more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as problem drinking (Stuart, Moore, Ramsey, & Kahler, 2004), which in turn may put them at an increased risk for subsequent life-threatening and impulsive behavior, such as suicide (Ellis & Trumpower, 2008; McFarlane et al., 2005). This proposed model informs the analyses conducted in the current paper.

In keeping with this proposed model, alcohol use has already been recognized as a significant risk factor for suicide ideation and suicide attempts among college students (Shaffer, Jeglic, & Stanley, 2008; Stephenson, Pena-Shaff, & Quirk, 2006). Moreover, college students who reported higher rates of alcohol use relative to other students were at an increased risk of engaging in suicidal behaviors (Brener, Hassan, & Barrios, 1999). Lamis, Malone, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, and Ellis (in press) found that frequency of alcohol use was associated with suicide proneness in a sample of 318 college students. Additionally, Powell and colleagues (2001) found that drinking frequency, drinking quantity, binge drinking, alcoholism, and immediate prior drinking were all directly and significantly associated with nearly lethal suicide attempts. These findings suggest that the use of alcohol may have both proximal and distal effects on suicidal behavior. Further, among alcohol-dependent individuals, younger age and female gender have been associated with suicide attempts (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., in press; Preuss et al., 2002).

Thus, there have been several previous studies examining involvement in intimate partner psychological abuse and alcohol use (e.g., Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Shannon, Logan, Cole, & Walker, 2008), alcohol use and suicidal behaviors (e.g., Lamis, Ellis, Chumney, & Dula, 2009), and involvement in intimate partner psychological abuse and suicidal behaviors (e.g., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, et al., 2009; Reviere et al., 2007); however, few existing studies have simultaneously considered the relationships among these three variables in women and none have simultaneously considered these relationships among college women. Moreover, the findings that have previously been obtained with adult women have been inconclusive. Specifically, some studies have failed to find associations among involvement in partner abuse, alcohol use, and suicidal behaviors (e.g., Heru, Stuart, Rainey, Eyre, & Recupero, 2006; Kaslow et al., 1998); whereas others have documented significant relationships among these variables (e.g., Kaslow et al., 2002; Gerevich & Bácskai, 2006; Wingwood, DiClemente, & Raj, 2000). In addition to these self-report investigations, one study (Olson et al., 1999) examined autopsy reports and related medical files for 313 female suicide deaths over a five-year period. Results indicated that experiences of intimate partner abuse or interpersonal conflict were associated with almost half of suicide deaths in women under the age of 40 years (Olson et al., 1999). Furthermore, Olson and colleagues found that approximately one-third of the women had alcohol present in their bodies at the time of death and twenty percent had a documented history of alcohol and/or drug abuse.

Therefore, the current study will address a gap in the literature by focusing on college women. It will also expand on the available research by investigating alcohol-related problems as a possible mediator in the relation between involvement in intimate partner psychological abuse (hereafter referred to as psychological abuse involvement) and suicide proneness in college women. Suicide proneness was assessed by the Life Attitudes Schedule (LAS-SF; Rohde, Lewinsohn, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Langford, 2004), which is a recently developed instrument that has been successfully used to identify individuals who have previously engaged in suicidal and life-threatening behaviors (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Lamis, 2008). The LAS-SF consists of items pertaining to various health-related thoughts, behaviors, and emotions that have been shown to correlate with a variety of health-compromising behaviors, including suicidality (Ellis & Trumpower, 2008; Rohde, Seeley, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Rohling, 2003). Use of this measure to assess suicide proneness and its associations with alcohol-related problems and psychological abuse in college students will thus extend the existing literature on the suicidal behavior of young adults. Specifically, on the basis of existing literature and consistent with theory, we hypothesized that: (1) reports of involvement in psychological abuse would be significantly and positively correlated with alcohol-related problems; (2) alcohol-related problems would be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness; and (3) alcohol-related problems would mediate the relation between involvement in psychological abuse and suicide proneness in college women.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 709 undergraduate women at a large southeastern university who volunteered to participate in the study in return for extra credit. Demographic characteristics of the sample were as follows: 100% female, 76.2% European American, 15.0% African-American, 4.2% Asian-American, <1% Native-American, <1% Hispanic, and 3.7% “Other”. The average age was 19.6 years (Median = 19.0, SD = 2.46) and ages ranged from 18 to 47 years. The sample consisted of college freshmen (46.3%), sophomores (27.4%), juniors (15.9%), and seniors (10.6%). Seventy-three percent of the students reported that were a member of a fraternity or sorority and the majority of them indicated that they either lived in residence halls on campus (53.2%) or off campus, but not with their parents (33.4%). Last, current relationship status was assessed for the total sample. Fifty-two percent of the participants reported they were single, 41.3% reported they were in a relationship, 2.4% were engaged, 1.8% were married, and less than one percent were divorced.

Measures

The Conflict Tactics Scales-2 (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) consists of 78 self-report items arranged in 39 item pairs, assessing both positive and negative relationship behaviors that may occur in the context of relationship conflict. The CTS2 includes 5 subscales designed to tap into abusive behaviors (psychological aggression, physical aggression, sexual coercion), positive conflict resolution strategies (negotiation), and outcomes associated with physical forms of abuse (injury). The psychological aggression subscale of the CTS2 was used in the present study, although participants completed the entire scale. Because of the high occurrence rate of involvement in psychologically abusive relationship behaviors, it was possible to use responses to these items to derive a continuous index of involvement in psychological abuse that had reasonable psychometric properties as described below.

The paired items on the CTS2 psychological aggression scale ask participants to report acts that they have committed towards a partner (perpetration), as well as acts committed by a partner towards them (victimization). The psychological aggression perpetration subscale consists of 8 items (e.g., “I called my partner fat or ugly”) and the psychological aggression victimization subscale also consists of 8-items (e.g., “My partner insulted or swore at me”). Although the two scales measure different psychologically aggressive behaviors (i.e., perpetration vs. victimization), they were highly correlated with one another in the current sample (r = .89; p < .001), and indicated that there was a large amount of reciprocity and bi-directionality between these behaviors, we created a combined index that would avoid Type I error inflation.1 Thus, the newly formed variable (psychological abuse involvement) reflects the totality of each college woman’s involvement in a psychologically abusive relationship (perpetration and victimization). As described by the authors of the CTS2, each question on the measure is rated on a scale of 0 to 6 (has never happened, happened 1 time, 2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, 11–20 times, more than 20 times). In the current study, the raw responses were summed and then averaged to reflect the frequency of psychological abuse involvement during the last year. The midpoint substitution method suggested by Straus et al. (1996) was not used for the frequency scores because it exacerbates the skew inherent in the distributions of the psychological aggression variable and thereby further violates the assumption of normal distribution underlying tests of statistical significance. In this study, the internal consistency reliability estimate for women’s reports of being involved in a psychologically aggressive relationship on the CTS2 was .90.

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) was used to assess alcohol-related problems common among college students (e.g., missing class, getting into fights or arguments, driving after drinking). The RAPI assesses the occurrence of 23 alcohol-related problems within the last year using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 1 = 1–2 times, 2 = 3–5 times, 3 = 6–10 times, 4 = more than 10 times). Scores can range from 0 to 92. In the current study, the total score on the RAPI was positively skewed (1.71) and leptokurtic (3.76), so we conducted a natural log transform of the score (plus one) to address normality issues with resulting skewness being acceptable (−.36) and slightly negative kurtosis (−1.04). The RAPI has regularly demonstrated good internal consistency in college student samples (e.g., Cronbach’s α = 0.92, Carey & Correia, 1997). Similarly, in the present study, the internal consistency reliability estimate for the RAPI was .94.

The Life Attitudes Schedule-Short Form (LAS-SF; Rohde et al., 2004) was used to assess current suicide proneness. The LAS-SF short form is a 24-item version of the original Life Attitudes Schedule (LAS; Lewinsohn, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Rohde, & Langford, 2004); both measures are at the 4th-grade reading level and have been shown to relate significantly to a wide variety of unhealthy and risk taking behavior (Rohde et al., 2003). Underlying the LAS measures is a theoretical model in which suicide proneness is defined broadly to consist of: 1) overtly suicidal behavior and death-related behaviors (e.g., I enjoy thinking about death); 2) risk and injury behaviors (e.g., sometimes I think about injuring myself); 3) lack of health and illness-prevention behaviors (I try to eat foods that are good for me); and 4) lack of self-enhancement behaviors (e.g., I rarely do things that violate my standards). Participants report whether each item was true or mostly true, or false or mostly false, for them during the past seven days. To score the LAS-SF, negative responses to positive items are reversed so that higher scores indicate greater engagement in suicide-prone behavior. The LAS-SF has been shown to have good psychometric properties (α = .78) and correlates significantly with both current suicide ideation (r = .23, p < .001) and a history of past suicide attempts (r = .32, p < .001; Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Lamis, 2008). It has been used successfully with college students in previous studies (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Arata, Bowers, O’Brien, & Morgan, 2004). The coefficient alpha for the 24 LAS-SF items in the current sample was .73.

In addition to demographic variables (age, race), participants self-reported on social club membership (i.e., fraternity/sorority affiliation), relationship status, and residency status (e.g., Greek housing, off-campus apartment), all of which may provide social support and a sense of belonging to an individual experiencing distress during college life. These support networks may serve as protective factors against one’s propensity to engage in suicidal behaviors (Joiner, 2005) and were included in the mediation model as possible covariates.

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained from the university’s Institutional Review Board and ethical procedures were followed in the collection of these data. Data collection was conducted over the course of two semesters with approximately equal numbers of participants completing the study during the fall semester and spring semester. Participants voluntarily chose to complete this online survey outside of class time in return for modest extra credit in one of their psychology courses. Students were told of the study in regularly scheduled classes and through posting on the online participant pool. Participants completed a demographic survey and the measures, which were presented in a randomized order. Prior to data collection, electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were advised that some items in the survey were personal in nature but that the study was anonymous and the information gathered would not be traceable to specific individuals. At the same time, participants were advised that they were free to leave any items blank that they were not comfortable answering honestly. No negative reactions were reported by any participants or observed by the investigators.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the three primary study variables – involvement in psychological abuse in a relationship, (log-) alcohol-related problems, and suicide proneness, are presented above the diagonal in Table 1. Partial correlations of the three variables, covarying age, race/ethnicity, living situation, social club membership, and relationship status appear below the diagonal. All three correlations are positive and significant, p’s < .01, regardless of the inclusion of covariates. These results are consistent with Hypothesis One (psychological abuse involvement would be significantly and positively correlated with alcohol-related problems) and Hypothesis Two (alcohol-related problems would be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness).

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix, Means, and Standard Deviations of Study Measures

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological Abuse Involvement | -- | .26 | .25 |

| 2. Alcohol Related Problems (log-transformed) |

.31 | -- | .42 |

| 3. Suicide Proneness | .27 | .41 | -- |

| Mean | 1.03 | 12.27a | 4.76 |

| SD | 0.88 | 13.45a | 3.26 |

| Range | 0 – 4.25 | 0 – 80a | 0 – 21 |

Note. N = 709. Tabled values are zero-order correlations (above diagonal) and partial correlations (below diagonal) after covarying out age, ethnicity, living situation, social club membership, and relationship status. All values are significant, p’s < .01.

Non-transformed

The third hypothesis, that alcohol-related problems would mediate the relation between psychological abuse involvement and suicide proneness in college women, is a conventional three-variable mediation system, as described in any standard treatment of indirect effects (e.g., MacKinnon, 2008), with the addition of the suite of covariates. The null hypothesis is that the product of the two paths – from the predictor (psychological abuse involvement) to the mediator (alcohol-related problems) and from the mediator to the outcome (suicide proneness) is equal to zero, indicating no indirect effect.

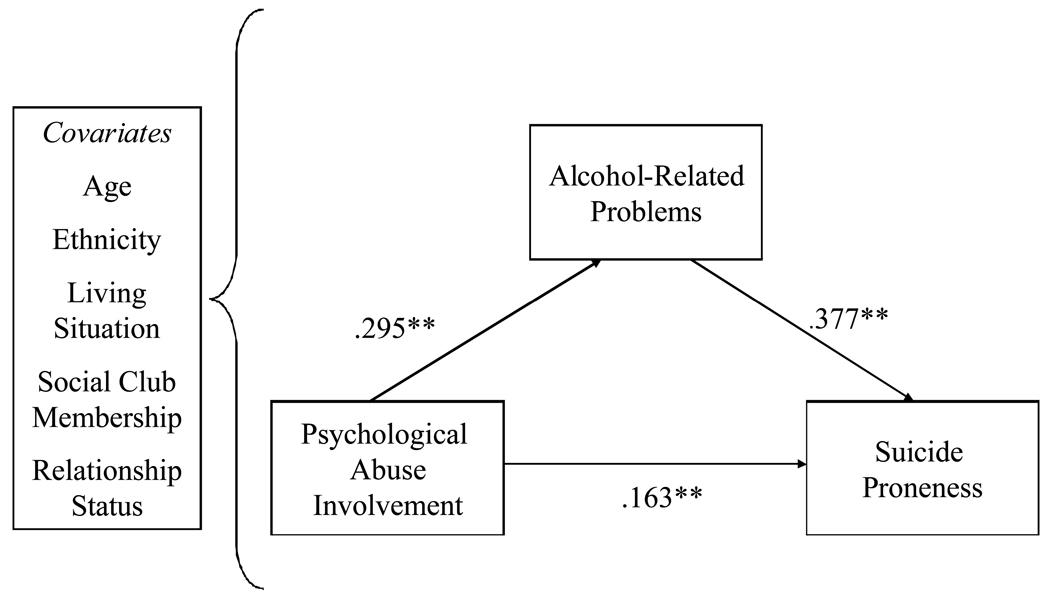

We estimated the mediation model as a path analysis in Mplus v.5.2 (L. K. Muthén & B. O. Muthén, 2009), with the covariates modeled as exogenous variables predicting each of the three study variables in a saturated model and using that software’s facility for maximum likelihood estimation in the context of missing data. The direct effect between relationship psychological abuse involvement and suicide proneness was significant, b = 0.60, SE = 0.15, Est./SE = 4.13, p < .001; the direct effect between relationship psychological abuse involvement and alcohol-related problems was also significant, b = 0.41, SE = 0.05, Est./SE = 8.69, p < .001; and the direct effect between alcohol-related problems and suicide proneness was significant as well, b = 0.99, SE = 0.11, Est./SE = 9.09, p < .001. Key results appear in Figure 1. Consistent with the recommendations of Mackinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004), we used the asymmetric confidence limits for the indirect effect, as computed by the software PRODCLIN (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). The unstandardized point estimate of the indirect effect was 0.41, 95% confidence interval: 0.29 – 0.55. The confidence interval excluded zero, indicating a significant indirect effect of psychological abuse involvement on suicide proneness via alcohol-related problems. This result is consistent with our third hypothesis. As noted in Footnote 1, and as would be expected on the basis of the strong positive correlation obtained between reports of psychological abuse perpetration and victimization, the model remained significant and the findings reported above were essentially unchanged when reports of perpetration and victimization were considered separately.

Figure 1.

Mediational model with standardized regression coefficients.

Note. ** p< .01.

Discussion

The present study explored the associations among psychological abuse involvement, alcohol-related problems, and suicide proneness in college women. Past research (e.g. Kaslow et al., 2002) has suggested that these variables are related; however, the results have been inconclusive. Further, previous studies have not reported findings investigating alcohol-related problems as a potential mediator in the relation between psychological abuse and suicide proneness among college women and no existing studies have used a measure that assesses current suicide proneness rather than past suicidal behaviors. Consequently, the current study addresses an important gap in the literature by examining this mediational model in college student women.

The results indicated that screening individuals for psychological abuse involvement and alcohol-related problems has the potential to aid in the prediction of suicide prone behaviors among college women. As expected, being involved in a psychologically abusive relationship was significantly positively correlated with experiencing alcohol related problems. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that women with alcohol-related problems are at an increased risk for being perpetrators and/or victims of intimate partner abuse (e.g., Caetano et al., 2001; Stuart et al., 2004). One interpretation of this finding is that women who use alcohol more frequently may increase their likelihood of partnering with more aggressive, abusive, and/or impulsive men. A second interpretation of this result is that alcohol may function to disinhibit college men and women such that they are more likely to express their relationship distress more destructively and abusively to one another. A third explanation of this finding is that the relationship between alcohol-related problems and psychological abuse involvement is the result of a third factor (e.g., personality characteristics, socioeconomic circumstances) that encourages the expression of both drinking and partner psychological abuse. A fourth interpretation of this finding, in keeping with our proposed model, is that women who are victims and/or perpetrators of psychological abuse in their intimate relationships may turn to alcohol as a coping mechanism for the emotional pain associated with their abusive experiences, which may then place them at an increased risk of developing and experiencing alcohol-related problems. This explanation is in accordance with Testa and Leonard’s (2001) initial supposition that women may use alcohol to cope with or escape the interpersonal conflict which may arise from continuous psychological abuse in the intimate relationship. The current research advanced this supposition a step by showing a relation between psychological abuse involvement and self-reported alcohol-related problems, given that studies have consistently shown an association between initial alcohol consumption and the development of later alcohol problems in college students (Neighbors, Walker, & Larimer, 2003; Park, 2004). However, further work is needed to tease out the precise relationships between either perpetration of psychological abuse or victimization from psychological abuse; the high correlation between these behaviors in the current sample precluded this.

As anticipated, reporting alcohol-related problems was shown to be significantly and positively correlated with suicide proneness. This result suggests that college women who experience problems in their lives related to alcohol may be at an increased risk for suicide or suicide-related behaviors. This finding is not surprising in light of prior research (e.g., Windle & Windle, 2006) documenting an association between alcohol-related problems and suicidal behaviors in college students. One potential explanation of this finding is that the negative consequences that may arise from alcohol use and abuse (e.g., legal problems, serious injury) could possibly cause enough distress in an individual’s life that he/she contemplates suicide. However, other researchers (e.g., Ellis & Trumpower, 2008; Strosahl, 2004) propose that problem drinking is a subtle form of suicidality, and so these variables will naturally cluster together. It is also possible that individuals who feel hopeless about their lives contemplate suicide and fail to regulate their drinking behaviors. Likewise, impulsivity might be a third variable that explains both a greater likelihood of experiencing alcohol problems and a greater tendency toward engaging in suicide prone and life-threatening behaviors. Continued research disentangling the nature of these relations across time will be essential.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine alcohol-related problems as a mediator between psychological abuse involvement and suicide proneness in a sample of college women. One previous study (Kaslow et al., 1998) utilized a similar mediational analysis in a sample of 285 hospitalized African-American women. This study failed to find mediation; however, there were a number of measurement and methodological differences between the two studies. One particular difference included comparing hospitalized suicide attempters to non-attempters in the Kaslow et al. sample versus utilizing a convenience sample of college women who reported on their current suicide proneness in the present study. Another important difference was that suicide attempt status was the outcome variable in the Kaslow et al. study, whereas a more indirect measure of suicide risk (i.e., LAS-SF) was used in the current study.

Consistent with our third hypothesis, alcohol-related problems emerged in the current study as a significant mediator of the relation between psychological abuse involvement and suicide proneness. This finding provides support for the proposed mediational model and suggests that college women involved in a psychologically abusive relationship may be more prone to engage in suicidal behaviors due in part to their encounters with alcohol-related problems. Specifically, it is possible that college women initially use alcohol to cope with the negative response of being in an abusive relationship, which may make them more susceptible to experiencing problems associated with alcohol, which may ultimately increase their negative mood and promote their likelihood of engaging in suicidal behaviors. However, future longitudinal research will be needed to clarify the causal relationships among these variables.

Several limitations in the present study should be noted. First, the sample consisted predominantly of young adult European-American college women. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to other populations, such as older students and minorities. Replication of these results across samples and populations will be necessary. Second, there may be several other possible mediators that could help account for the obtained relation between psychological abuse involvement and suicide proneness. Variables to consider might include social support, depression, PTSD, drug use, and hopelessness. Future research should examine these other possible mediators in greater detail. Third, the current study was limited to self-report data, which raises the potential problem of bias due to socially desirable responding and increases the chances of finding associations that are due to shared method variance, rather than demonstrating real relationships among constructs. Future studies should utilize a multi-modal data collection strategy with college women. Fourth, participants were asked to report on relationship and alcohol-related behaviors that occurred within the past year, which, given the large proportion of freshmen in our sample, could have happened while they were still in high school. Future researchers should consider a timeline for asking the target population when certain behaviors may have occurred and inquire about these behaviors accordingly. Last and perhaps most importantly, this study relied exclusively on data collected using a cross-sectional research design. Although mediational analyses were conducted, the methodology used to collect these data precludes a causal interpretation of associations among variables. More sophisticated methodologies and longitudinal designs should be employed before causal inferences can be made regarding the directional and developmental pathways that connect these variables in college women.

In spite of these limitations, the current findings support the value of conducting research in this understudied area. The results from the present work take a step toward elucidating the nature of the relations among psychological abuse involvement, alcohol-related problems, and suicide proneness in women attending college. The obtained findings may have practical implications. For example, college counseling centers should assess students for their involvement in psychologically abusive intimate relationships as well as their experiences with alcohol-related problems if and when a student is suspected of being at risk for suicidal and/or health-diminishing behaviors. In addition to assessment, prevention programs which target these identified risk factors for suicidality should be developed specifically for college women. The degree to which existing drug and alcohol prevention programs work to reduce suicide proneness should also be studied empirically. Improved programs that can be shown to empirically reduce the likelihood of a number of negative health outcomes are needed for college women.

Footnotes

We ran both the psychological abuse perpetration and victimization analyses separately and found the same pattern of significant results as we did for the combined score.

Contributor Information

Dorian A. Lamis, University of South Carolina.

Patrick S. Malone, University of South Carolina

Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling, University of South Alabama.

References

- American College Health Association. National college health assessment: Reference group executive summary spring. Baltimore: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. Perpetrator or victim? Relationships between intimate partner violence and well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez M, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Suicidal behavior in young women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener DA, Hassan S, Barrios L. Suicidal ideation among college students in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:1004–1008. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi C. Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health. 2001;25:58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi C, Schafer J, Clark C. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide trends among youths and young adults aged 10–24 years—United States, 1990–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56:905–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase K, O'Farrell T, Murphy C, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Factors associated with partner violence among female alcoholic patients and their male partners. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:137–149. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker A, McKeown R, Sanderson M, Davis K, Valois R, Huebner E. Severe dating violence and quality of life among South Carolina high school students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:220–227. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker A, Smith P, Thompson M, McKeown R, Bethea L, Davis K. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11:465–476. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy W, Schwartz M. Woman abuse on campus. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Gaeta T, Schilling R, et al. Intimate partner violence and substance abuse among minority women receiving care from an inner-city emergency department. Women’s Health Issues. 2003;13:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TE, Trumpower D. Health risk behaviors and suicidal ideation: A preliminary study of cognitive and developmental factors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:251–259. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C, Caetano R. Ethnic differences in intimate partner violence in the U.S. general population: The role of alcohol use and socioeconomic status. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5:303–317. doi: 10.1177/1524838004269488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D, Bradley R, Laughlin J, Burke L. Risk factors and correlates of dating violence: The relevance of examining frequency and severity levels in a college sample. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:365–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary D. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossos N, Neighbors C, Kayesen D, Hove MC. Intimate partner violence perpetration and problem drinking among college students: The Roles of expectancies and subjective evaluations of alcohol aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:706–713. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerevich J, Bácskai E. Intimate partner violence, suicidal intent, and alcoholism. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:2033–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover A, Kaukinen C, Fox K. The relationship between violence in the family of origin and dating violence among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heru AM, Stuart GL, Rainey S, Eyre J, Recupero PR. Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence and associations with family functioning and alcohol abuse in psychiatric inpatients with suicidal intent. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:23–29. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U. S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of the Studies of Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE., Jr . Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow N, Thompson M, Meadows L, Jacobs D, Chance S, Gibb B, et al. Factors that mediate and moderate the link between partner abuse and suicidal behavior in African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Thompson M, Meadows L, Chance S, Puett R, Hollins L, et al. Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American Women. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12:13–20. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<13::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow N, Thompson M, Okun A, Price A, Young S, Bender M, et al. Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:311–319. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernic M, Wolf M, Holt V. Rates and relative risk of hospital admission among women in violent intimate partner relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1416–1420. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP, Woods CR, Sinal SH, Lawless MR, DuRant RH. Gender differences in risk behaviors among adolescents who experience date fighting. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1286–1292. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Ellis JB, Chumney FL, Dula CS. Reasons for living and alcohol use among college students. Death Studies. 2009;33:277–286. doi: 10.1080/07481180802672017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Malone PS, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Ellis TE. Body investment, depression, and alcohol use as risk factors for suicide proneness in college students. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000012. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Controversies involving gender and intimate partner violence in the United States. Sex Roles. 2009 Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9628-2. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Arata C, Bowers D, O’Brien N, Morgan A. Suicidal behavior, negative affect, gender, and self-reported delinquency in college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:255–266. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.3.255.42773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Friend J, Powell A. Adolescent suicide, gender, and culture: A rate and risk factor analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Lamis DA. Current suicide proneness and past suicidal behavior in adjudicated adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:415–426. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Sanders A, Crane M, Monson CM. Gender and history of suicidality: Are these factors related to U.S. college students’ current suicidal thoughts, feelings, and actions? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1998;28:127–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Snarr JD, Slep AMS, Heyman R. Using a large-scale survey to determine individual, family, work, and community correlates of suicide ideation for U.S. air force members; Poster presented at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Suicidology; San Fransisco, CA. 2009. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Leiner AS, Compton MT, Houry D, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence, psychological distress, and suicidality: A path model using data from African-American women seeking care in an urban emergency department. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Rohde P, Langford RA. Attitudes Schedule (LAS): A risk assessment for suicidal and life-threatening Behaviors. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 2004. Technical Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Watson K, Batten E, Hall I, et al. Intimate partner sexual assault against women and associated victim substance use, suicidality, and risk factors for femicide. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:953–967. doi: 10.1080/01612840500248262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, v.5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Expectancies and evaluations of alcohol effects among college students: Self-determination as a moderator. Journal on the Studies of Alcohol. 2003;64:292–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufield J, McNamera JR, Ertl M. Incidence and prevalence of dating partner abuse and its relationship to dating practices. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Olson L, Huyler F, Lynch A, Fullerton L, Werenko D, Sklar D, et al. Guns, alcohol, and intimate partner violence: The epidemiology of female suicide in New Mexico. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 1999;20:121–126. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.20.3.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell K, Kresnow J, Mercy J, Potter L, Swann A, Frankowski R, et al. Alcohol consumption and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;32:30–41. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.30.24208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss U, Schuckit M, Smith L, Danko G, Buckman K, Bierut L, et al. Comparison of 3190 alcohol-dependent individuals with and without suicide attempts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reviere S, Farber E, Twomey H, Okun A, Jackson E, Zanville H, et al. Intimate partner violence and suicidality in low-income African American women: A multimethod assessment of coping factors. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:1113–1129. doi: 10.1177/1077801207307798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Langford R. Life Attitudes Schedule: Short Form (LAS-SF): A risk assessment for suicidal and life-threatening behaviors. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 2004. Technical Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Seeley JR, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Rohling ML. The Life Attitudes Schedule-Short Form: Psychometric properties and correlates of adolescent suicide proneness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:249–260. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.3.249.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer M, Jeglic EL, Stanley B. The relationship between suicidal behavior, ideation and binge drinking among college students. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12:124–132. doi: 10.1080/13811110701857111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon L, Logan T, Cole J, Walker R. An examination of women's alcohol use and partner victimization experiences among women with protective orders. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:1110–1128. doi: 10.1080/10826080801918155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BA, Thompson S, Tomaka J, Buchanan AC. Development of the Intimate Partner Violence Attitude Scales (IPVAS) with a predominantly Mexican American college sample. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson H, Pena-Shaff J, Quirk P. Predictors of college student suicidal ideation: Gender differences. College Student Journal. 2006;40:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Stith S, Smith D, Penn C, Ward D, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Ramirez I. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:281–290. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosahl KD. ACT with the multi-problem patient. In: Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, editors. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Springer; 2004. pp. 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Moore T, Ramsey S, Kahler C. Hazardous drinking and relationship violence perpetration and victimization in women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:46–53. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Newton, MA: Education Development Center, Inc; 2004. Promoting mental health and preventing suicide in college and university settings. [Google Scholar]

- Temple J, Weston R, Stuart G, Marshall L. The longitudinal association between alcohol use and intimate partner violence among ethnically diverse community women. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1244–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Leonard KE. The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed simple. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ, Kingree JB, Pruett R, Thompson NJ, Meadows L. Partner abuse and posttaumatic stress disorder as risk factors for suicide attempts in a sample of low-income, inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:59–72. doi: 10.1023/A:1024742215337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Kaslow N, Short L, Wyckoff S. The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:942–949. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T, Allen J, Hopper E, Maglione M, McLaughlin D, McCullough M, et al. Mediators of suicidal ideation within a sheltered sample of raped and battered women. Health Care for Women International. 2007;28:478–489. doi: 10.1080/07399330701226453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson T, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Chen P. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle R. Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults: Epidemiology, neurobiology, prevention, and treatment. New York, NY US: Springer Science; 2006. Alcohol consumption and its consequences among adolescents and young adults; pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wingwood GM, Diclemente RJ, Raj A. Adverse consequences of intimate partner abuse among women in non-urban domestic violence shelters. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:270–275. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A, Morales M, McCabe S, Boyd C, D'Arcy H. Drinking like a guy: Frequent binge drinking among undergraduate women. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40:241–267. doi: 10.1081/ja-200048464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]