Abstract

Drug treatment courts (DTCs) provide substance abuse treatment and case management services to offenders with substance use disorders as an alternative to incarceration. Studies indicate that African-Americans less frequently complete DTC programming. The current study analyzed data from the Dane County Drug Treatment Court (n = 573). The study ascertained factors associated with failure to complete treatment among African-American DTC participants. Significant factors were unemployment (p = 0.011), previous criminal history (p = 0.013), and, possibly, the presence of a cocaine use disorder (p = 0.064). Treatment plans for DTC participants should incorporate services addressing needs specific to African-Americans, who are over-represented in the U.S. correctional system. The current results indicate that employment, prior corrections involvement, and the presence of a cocaine use disorder may be specific issues to consider.

Keywords: drug court, drug offenders, substance abuse, health disparities, African-Americans

Introduction

Criminal justice involvement and incarceration occur disproportionately among African-Americans vs. other ethnic groups in the U.S. In 2001, the lifetime rate of prison time for African-American males was nearly 17%, over six times higher than the lifetime rate for Caucasian males.(Bonczar 2003) African-American females were similarly over-represented (nearly 6 times more likely to be incarcerated) when compared to their white counterparts. Between nine and ten percent of U.S. African-American males age 15–29 were in prison at year-end 2003. This contrasts starkly from 1.1% of white males, and 2.6% of Hispanic males in the same age group.(Harrison and Beck 2006)

Substance use and underlying substance use disorders account for a plurality, if not the majority, of an increasing burden on the U.S. criminal justice system. In 2002, 75% of convicted drug offenders met substance dependence or abuse criteria, and 25% of drug offenders reported committing their crime in order to get money for drugs.(Mumola and Karberg 2006) African-Americans are dramatically over-represented among this segment of the criminal justice population, as well. In 2002, 43% of felons convicted of drug offenses were African-American.(Durose and Langan 2004) Twenty-four percent of African-American inmates in state prisons were incarcerated for drug offenses, markedly higher than rates for Caucasian inmates (14%). This disproportion persists despite similar rates of illicit drug use among whites and African-Americans. The 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found rates of substance abuse and dependence which were virtually indistinguishable at 9.3 and 9.5 percent respectively. Rates of past month use were marginally higher for African-Americans (9.7%) than for whites (8.4%), but certainly not to an extent that explains the dramatic differences in corrections involvement for drug-related offenses.(SAMHSA 2007)

As the number of arrests for drug offenses continues to rise, treatment-based alternatives to incarceration for drug-involved offenders, such as drug treatment courts (DTCs), gain more attention. The drug court system is based on a treatment rather than punishment model and aims to reduce criminal recidivism by treating the often underlying substance abuse or dependence.

A review of multiple DTCs determined that both crime and relapse to regular drug use are diminished during participation, and that re-arrest rates are lower among drug court participants than among typically adjudicated drug offenders.(Belenko 2001) Unfortunately, it appeared in this systematic review that African-Americans may have lower graduation rates from these programs than do other ethnic groups. While small cross-sectional studies and process evaluations within individual DTCs have failed to discover a difference in completion rates by ethnicity,(Harrell and Smith 1996; Fetros 1998) a large national study(Roman, Townsend et al. 2002) obtained contrary results. Regression analysis of a national sample (N = 2021) of drug court participants found that African-American ethnicity related significantly to increased rates of post-program recidivism vs. whites and vs. other minority groups. This is a concerning finding, particularly in a large sample where the majority (55%) were African-American.

Given the potential effectiveness of alternatives to incarceration and apparent racial disparities in their success, closer examination of the drug court experiences of African-Americans is warranted. Prior studies have shown reduced graduation rates among those with less education and those with cocaine use disorders(Peters, Haas et al. 1999; Brown 2009); both characteristics have previously been associated with African-American race in the general adult population.(Ma and Shive 2000)

African-Americans in the drug court system are more likely to be unemployed at time of entry, and employment status has been shown to be a significant factor in predicting substance abuse treatment completion among drug court participants (Dannerbeck, Harris et al. 2006). In addiction treatment research employment is viewed as both a desired outcome as well as an element of treatment (Platt 1995). Substance users who are employed and/or have access to employment related services have a higher likelihood of drug and alcohol treatment success (Platt 1995). Employment has also been found to minimize relapse and reduce involvement in criminal activity for the recovering drug addict (Vaillant 1988; Platt 1995; Butzin, Martin et al. 2002). Separate studies have also indicated that being Caucasian (Sechrest and Schicor 2001) and being employed before and during DTC is a predictor of drug court graduation (Hartley and Phillips 2001). While these individual studies have identified employment and race as key variables in drug treatment court success, the particulars of ethnicity in combination with employment status as an outcome for DTC has rarely been undertaken in published studies.

The current study sought to examine participant historical factors (sociodemographic, legal, and substance use) associated with failure to complete substance abuse treatment among African-Americans in the Dane County Drug Treatment Court. We hypothesize that specific factors (unemployment, educational attainment, primary substance of misuse) often associated with ethnicity in previous studies, rather than ethnicity per se, will predict treatment completion vs. failure.

Methods

Setting/sample

The data for this study is derived from administrative information collected by a single DTC in a Midwestern U.S. state from 1996–2004. The DTC for the current study was established in 1996. A single drug court judge presided over all cases during the years in question (1996–2004). Though abstinence from illicit substances is a goal and contracting community treatment facilities are abstinence-based in philosophy, participants may not receive sanctioning due to a single positive urine drug screen, if making progress in other areas, such as attendance to treatment visits, education, or employment. In this sense, the DTC could be considered more closely affiliated with harm reduction than abstinence-based philosophies. The case load for the Dane County DTC has ranged from 70–100 participants in each year of its existence from 1996–2004. Assignment to treatment modality and other case management is guided by the clinical impression of the assessor at the Clinical Assessment Unit as to the addiction severity of the individual. To date, specific services based upon ethnicity or gender have not been available.

Data were obtained from administrative information collected by staff of the Dane County DTC and the Treatment Alternatives Program, the community-based organization providing case management services to participants in the Dane County DTC. African-American participants during program years 1996–2004 were included in the analysis (n = 97).

Analysis

Means comparisons using independent Student’s t-testing (continuous variables) and cross-tabulations using Pearson’s chi-squared (categorical variables) were conducted versus Caucasian participants (n = 454). Data included demographic characteristics, legal history, and substance use history from questionnaire and interview at the time of referral as well as information from the DTC program database, which tracks progress of participants through the drug court.

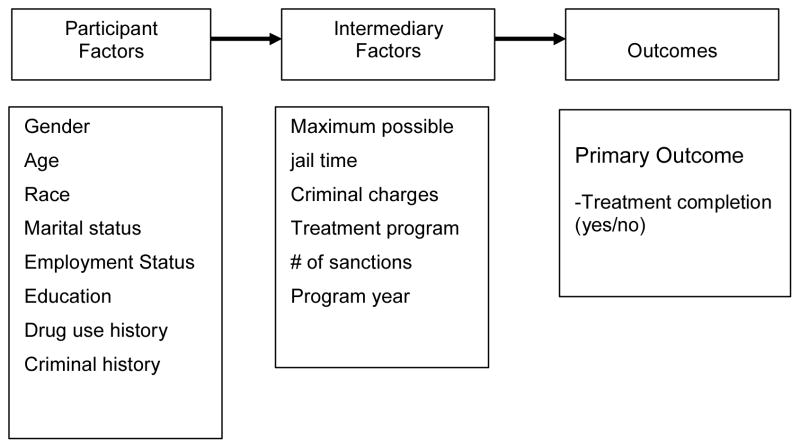

Measures in the dataset and the theoretical framework guiding stepwise logistic regression analysis are shown diagrammatically in Figure 1. Specific variables included: age at admission, self-reported ethnicity, marital status, gender, educational attainment in years, employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed), criminal history (numbers of felonies/misdemeanors, numbers of jail/prison sentences), substance use history (substances used, frequency of use, duration of use, route of use, number and type of prior treatment contacts), and program variables as shown in Figure 1 (program year, treatment modality, criminal charge, maximum possible jail time, sanctions during participation, and treatment completion/failure to complete treatment).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model guiding addition of variables to logistic regression model.

Dummy variables were created for categorical variables for purposes of logistic regression analysis. Continuous variables were examined for distributional characteristics and, if severely non-normal, transformed as appropriate to approximate normal distribution for purposes of initial bivariate associations and for regression modeling. Definitions of substance use variables were dummy-coded such that 0 = the substance was not a primary substance of abuse/dependence for the participant, 1 = the substance was a primary substance of abuse/dependence.

The primary dependent variable was coded such that 1 = failure to complete treatment and 0 = successful completion of treatment.

Statistical and theoretical considerations guided multivariate logistic regression modeling of significant associations between client characteristics and the binary outcome variable of treatment completion/failure. Bivariate associations achieving statistical significance were first added to the model in stepwise fashion for indicators of participant historical characteristics. After achieving a final model for the associations between participant factors and treatment completion, intermediary variables (treatment/case management factors) achieving significance were then added to achieve a final overall regression model.

SAS Version 9.1 statistical software was used to run all analyses.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the population of all participants in the Dane County DTC from 1996–2004 is predominantly Caucasian (79 percent). This prevalence is greater than some drug court samples,(Gottfredson and Exum 2002; Banks and Gottfredson 2003; Gottfredson, Najaka et al. 2003; Listwan, Sundt et al. 2003; Banks and Gottfredson 2004) but predominantly Caucasian samples are common in the literature on DTCs.(Brewster 2001; Sechrest and Schicor 2001; Carey and Marchand 2005; Marlowe, Festinger et al. 2005; Marchand, Waller et al. 2006)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at entry to drug treatment court, all participants during program years 1996–2004 (N=573).

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–20 | 162 (28.3) | |

| 21–25 | 102 (17.8) | |

| 26–30 | 82 (14.3) | |

| 31–35 | 73 (12.8) | |

| (x̄ = 29.27, sd = 9.85) | ||

| 36–40 | 63 (11.0) | |

| 41–45 | 52 (9.1) | |

| Over 45 | 38 (6.6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 454 (79.4) | |

| African-American | 97 (17.0) | |

| Latino | 17 (3.0) | |

| Asian/Pacific | 4 (0.7) | |

| Islander | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 383 (67.0) | |

| Female | 189 (33.0) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 378 (66.1) | |

| Married | 140 (24.5) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 54 (9.4) | |

| Educational Attainment | ||

| < 12 years | 155 (27.1) | |

| High School Grad | 288 (50.3) | |

| GED | 63 (11.0) | |

| Associate’s Degree | 33 (5.8) | |

| At Least Some College | 33 (5.8) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Unemployed | 205 (35.8) | |

| Part-Time | 94 (16.4) | |

| Full-Time | 264 (46.2) | |

The percentage of clients who are male and the mean age of the sample aligns with the majority of study samples. Other sample socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age, educational attainment, marital status, and employment status are comparable to other programs and other treatment-seeking samples.

The legal history and substance use history of samples are rarely presented in literature to date, making comparison on many parameters between this sample and others difficult to attain.

Power analysis for chi-squared testing for categorical variables indicated that the sample size provided greater than 87% power to detect a statistically significant difference between African-Americans versus Caucasians at a type 1 error rate (α) of 0.05. For means comparisons, equal variances were not assumed for purposes of power analysis. For the log number of offenses, the sample provided greater than 83% power to detect a difference equal to ¼ of one standard deviation from the mean at a type 1 error rate (α) of 0.05.

Means comparisons for continuous variables indicated a significant difference for age between African-American and Caucasian participants (African-American mean age = 31.4, Caucasian mean age = 28.8; p = 0.011). Differences between groups were non-significant for duration of use and the log number of prior offenses and log number of previous treatment contacts.

Pearson’s chi-squared testing of categorical variables is presented in Table 2. Variables achieving a statistically significant difference in African-American versus Caucasian participants were employment status (p = 0.011) and presence/absence of a past offense (p = 0.013). The mean for log number of offenses, however, did not differ between these groups (p = 0.11). The finding for a difference in primary substance of abuse/dependence trended toward significance. On chi-squared analysis of dummy variables created for individual substances, this trend appeared to be driven primarily by a nearly statistically significant difference in the likelihood of cocaine being the primary substance of abuse/dependence (p = 0.064). The prevalence of other substances did not approach significance.

Table 2.

Characteristics of African-American and Caucasian participants in the Dane County DTC and results of chi-squared testing for significant differences between African American versus Caucasian participants.

| African American N (%) | Caucasian N (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | p = 0.20 | ||

| Male | 59 (61) | 307 (68) | |

| Female | 38 (39) | 147 (32) | |

| Education | p = 0.39 | ||

| < 12 years | 31 (32) | 117 (26) | |

| High school grad | 52 (54) | 288 (63) | |

| Education beyond HS | 14 (14) | 49 (11) | |

| Employment | p = 0.029 | ||

| Full time | 39 (40) | 214 (47) | |

| Part time | 12 (12) | 78 (17) | |

| Unemployed | 46 (48) | 162 (36) | |

| Marital Status | p = 0.57 | ||

| Married | 28 (29) | 108 (24) | |

| Single | 60 (62) | 302 (66) | |

| Divorced/separated | 9 (9) | 44 (10) | |

| Primary substance | p = 0.066 | ||

| Alcohol | 24 (25) | 152 (33) | |

| Marijuana | 40 (41) | 155 (34) | |

| Cocaine | 23 (24) | 71 (16) | |

| Opioids | 10 (10) | 70 (16) | |

| Other | 0 | 6 (1) | |

| > 1 Substance Use Disorder | p = 0.11 | ||

| Yes | 80 (82) | 340 (75) | |

| No |

17 (18) | 114 (25) | |

| First Offense |

p = 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 33 (35) | 217 (48) | |

| No | 64 (65) | 237 (52) | |

Fifty-two percent (n = 50) of the African-American participants failed to complete substance abuse treatment. This did not differ significantly from the failure rate (42 percent) for Caucasian participants (p = 0.094).

A logistic regression model of treatment completion/failure was constructed based upon the significance of bivariate correlations between treatment completion/failure and each of the covariates appearing in Table 2. After stepwise iterative model building, the final logistic regression model of failure to complete treatment versus treatment completion found only the presence of prior offenses to be significantly predictive of failure to complete treatment (odds ratio for failure = 0.39 for no prior offenses versus presence of prior offenses).

Discussion

The current study failed to demonstrate a significant difference in treatment retention for African-Americans versus Caucasian participants. There were indications that group characteristics and, hence, service needs may differ between groups. African Americans in the sample were significantly more likely to be unemployed and to have prior criminal justice involvement. Though non-significant, a trend (p = 0.064) toward greater likelihood of cocaine as a primary substance of abuse or dependence existed for African-American participants. To provide further and clearer illustration of substance use by ethnicity, these data are summarized in Table 3. Previous findings of an association between cocaine use disorders and impulsivity provide a potential explanation for greater likelihood of treatment failure among cocaine using correctional clients. Cocaine use disorders have been associated with impulsive behavior, which would logically predispose to difficulty with treatment adherence and recidivism.(Moeller, Dougherty et al. 2001) Cocaine use has also been associated with other potentially detrimental social factors, such as lesser educational attainment, less social support, higher unemployment rates, concurrent alcohol consumption, and use of other illicit drugs.(Braun, Murray et al. 1996)

Table 3.

Poly-drug use in African American and Caucasian DTC participants with cocaine as primary substance.

| African American N (%) | Caucasian N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary substance | ||

| Cocaine | 23 (24) | 71 (16) |

| > 1 Substance Use Disorder | ||

| Yes | 19 (83) | 58 (82) |

| No | 4 (17) | 13 (18) |

The overall finding of similar rates of treatment completion for African-American and white participants in DTCs is in line with previous smaller studies,(Harrell and Smith 1996; Fetros 1998; Saum, Scarpitti et al. 2001)but contradicts findings in systematic review(Belenko 2001) and a large national sample.(Roman, Townsend et al. 2002) The sample size analysis (see Methods) provides some evidence that this result of the current study is not simply due to type 2 error, though this remains a possibility. The relatively small size of the Dane County DTC relative to more urban locales may explain this finding in part. A smaller offender case load could certainly foster more intensive individualized attention and potentially improve success rates in a subpopulation which would normally be at greater risk of failure to complete treatment. Additionally, continuity with a single drug court judge appears to foster improved outcomes.(Barton 2007)

Though significant on initial bivariate analysis, the lack of a significant association between treatment failure and employment status when other factors are held constant is of interest. In previous studies, unemployment has been predictive of failure to complete substance abuse treatment and of future recidivism.(Sechrest and Schicor 2001; Sung, Belenko et al. 2004; Sung and Belenko 2005) Additionally, interventions specifically targeting employment status have been shown to improve DTC outcomes.(Leukefeld, Webster et al. 2007) That unemployment dropped out of the regression model in the current study when criminal history was statistically controlled may indicate that employment status, in addition to being an important factor and outcome in and of itself, is also a marker for underlying factors which are more powerful drivers of the likelihood of treatment completion. Such unmeasured factors in the current study might include substance use disorder severity and/or the presence and severity of mental illness. The only experimental study to date which has examined mental health factors among drug court participants found that specifically anti-social personality disorder was associated with a need for more intensive supervision to attain positive outcomes.(Festinger, Marlowe et al. 2002) Factors potentially underlying employment status, such as mental illness presence and severity, may be more important contributors to or detractors from success in drug court than employment itself.

Similarly, criminal justice history is likely an indicator of other underlying factors. The presence and severity of mental illness, particularly anti-social personality disorder, is one such likely factor.(Marlowe, Festinger et al. 2006; Marlowe, Festinger et al. 2007) The presence of a cocaine use disorder is also a potential associated underlying factor.(Dannerbeck, Harris et al. 2006) To address and prevent recidivism effectively likely requires treatment and services particular to these underlying factors rather than, or in addition to, addressing criminal behavior per se. Studies examining the provision of employment training interventions to drug court participants indicate that improvement in employment outcomes (e.g. percent of income derived from illicit sources) is associated with reductions in recidivism, as well.(Leukefeld, Webster et al. 2007) In the setting of cocaine dependence, it appears that treatment matching may be an issue of importance. Specific interventions (manual-guided individual drug counseling(Crits-Christoph, Siqueland et al. 1999) and contingency management,(Poling, Oliveto et al. 2006) for example) may be more effective than others in the setting of cocaine dependence. Unfortunately, unlike opioid dependence or alcohol dependence, no pharmacologic agents have attained robust improvements for cocaine dependent subjects.(Arndt, Dorozynsky et al. 1992; Grabowski, Rhoades et al. 2000; Malcolm, Kajdasz et al. 2000; Schmitz, Averill et al. 2001; Brown, Nejtek et al. 2002; de Lima, Soares et al. 2002; Brown, Nejtek et al. 2003; Reid, Casadonte et al. 2005)

Limitations of the current study include the use of administrative data. Interview for obtaining measure of several of the study covariates, however, has been widely used and validated in previous studies. Measures in the current study of demographic and socioeconomic indicators are less likely to be open to such concerns. The lack of a specific validated measure of substance dependence severity, such as the Addiction Severity Index(McLellan, Kushner et al. 1992)or the Substance Dependence Severity Scale(Miele, Carpenter et al. 2001) may be a concern. The presence of multiple potential measures and the parallel nature of the assessments in the current study to validated measures may allay this concern to some degree. Measures on the ASI which are replicated by the interview conducted by drug court staff include employment status, marital status, ethnicity, educational attainment, lifetime substance use, primary problematic substance, route of use, prior treatment contacts, and previous legal charges. The structure of data in the current study parallels the structure of these items on the ASI. Items not present in the current data which would be assessed by an instrument such as the ASI include withdrawal symptoms, consequences (medical, occupational, legal, social) of substance use and their severity, and rater confidence in the client’s representation of information.

In summary, the findings of the current study indicated similar rates of substance abuse treatment completion for African-American and Caucasian participants in a drug treatment court. African-Americans in the sample, however, presented with a different set of historical concerns (unemployment, greater likelihood of prior criminal justice involvement, and, possibly, a greater prevalence of cocaine use disorders) which likely warrant specific services or modification of supervisory conditions. Vocational skills assessment and job placement services, mental health assessments and appropriate follow-up, and access to therapies shown to achieve positive outcomes in the setting of cocaine use disorders (such as cognitive behavioral therapy(Covi, Hess et al. 2002; Schmitz, Mooney et al. 2008) or contingency management(Tracy, Babuscio et al. 2007)) constitute services of likely importance in this subpopulation. Additionally, culturally sensitive case management and outreach with same-ethnicity staff(Terrell and Terrell 1984; Sussman, Robins et al. 1987; De Leon, Melnick et al. 1993; Beckerman, Fontana et al. 2001) may be important considerations for a population which may have reason to believe that the system has not treated them fairly in the past.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse 1 K23 DA017283-01A1

Contributor Information

Randall T. Brown, Department of Family Medicine PhD Candidate, Department of Population Health Sciences; University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Megan Zuelsdorff, Department of Family Medicine University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

- Arndt IO, Dorozynsky L, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP. Desipramine treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(11):888–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110052008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks D, Gottfredson DC. The Effects of Drug Treatment and Supervision on Time to Rearrest Among Drug Treatment Court Participants. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(2):385–412. [Google Scholar]

- Banks D, Gottfredson DC. Participation in drug treatment court and time to rearrest*. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21(3):637–658. [Google Scholar]

- Barton G. Baltimore City Drug Treatment Court: Process Evaluation. Portland, OR: NPC Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman A, Fontana L, Hennessy JJ, Pallone NJ. Drug courts in operation: Current research. New York, NY, US: Haworth Press; 2001. Issues of race and gender in court-ordered substance abuse treatment; pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S. Research on drug courts: A critical review, 2001 update. New York, NY: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974 –2001. Bureau of Justice Special Report 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Braun BL, Murray D, Hannan P, Sidney S, Le C. Cocaine use and characteristics of young adult users from 1987 to 1992: the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(12):1736–1741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster MP. An evaluation of the Chester County (PA) Drug Court Program. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31(1):177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Brown ES, V, Nejtek A, Perantie DC, Bobadilla L. Quetiapine in bipolar disorder and cocaine dependence. Bipolar Disorders. 2002;4(6):406–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ES, V, Nejtek A, Perantie DC, Orsulak PJ, Bobadilla L. Lamotrigine in patients with bipolar disorder and cocaine dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64(2):197–201. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009. Associations with substance abuse treatment completion among participants in drug court. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzin CA, Martin SS, Inciardi JA. Evaluating component effects of a prison-based treatment continuum. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2002;22(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey S, Marchand G. Malheur County Adult Drug Court (SAFE Court) Outcome Evaluation 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Covi L, Hess JM, Schroeder JR, Preston KL. A dose response study of cognitive behavioral therpy in cocaine abusers. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2002;23(3):191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, Muenz LR, Thase ME, Weiss RD, Gastfriend DR, Woody GE, Barber JP, Butler SF, Daley D, Salloum I, Bishop S, Najavits LM, Lis J, Mercer D, Griffin ML, Moras K, Beck AT. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(6):493–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannerbeck A, Harris G, Sundet P, Lloyd K. Understanding and Responding to Racial Differences in Drug Court Outcomes. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;5(2):1–22. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannerbeck A, Harris G, Sundet P, Lloyd K. Understanding and Responding to Racial Differences in Drug Court Outcomes. 2006;5(2):1–22. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leon G, Melnick G, Schoket D, Jainchill N. Is the therapeutic community culturally relevant? Findings on race/ethnic differences in retention in treatment. Journal of psychoactive drugs. 1993;25(1):77–86. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1993.10472594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima MS, Soares BG, Reisser AAP, Farrell M. Pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence: A systematic review. Addiction. 2002;97(8):931–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durose MR, Langan PA. Felony Sentences in State Courts, 2002. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Lee PA, Kirby KC, Bovasso G, McLellan AT. Status hearings in drug court: when more is less and less is more. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2002;68(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetros C. The Los Angeles County Drug Courts: Correlates of success. Long Beach, CA: California State University. M.S; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson D, Najaka SS, Kearley B. Effectiveness of drug courts: Evidence from a randomized trial. Criminology and Public Policy. 2003;2:171–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Exum ML. The Baltimore City Drug Treatment Court: One-Year Results From a Randomized Study. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39(3):337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Silverman P, Schmitz JM, Stotts A, Creson D, Bailey R. Risperidone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: randomized, double-blind trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;20(3):305–10. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell A, Smith B. Evaluation of the District of Columbia Superior Court Drug Intervention Program: Focus group interviews. Washington DC: National Institute of Justice; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Beck A. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2005. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2006 October 23 2007 from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/pjim05.pdf.

- Hartley RE, Phillips RC. Who graduates from drug courts? Correlates of client success. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2001;26(1):107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld C, Webster JM, Staton-Tindall M, Duvall J. Employment and drug use. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2007. Employment and work among drug court clients: 12-month outcomes; pp. 1109–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listwan SJ, Sundt JL, Holsinger AM, Latessa EJ. The Effect of Drug Court Programming on Recidivism: The Cincinnati Experience. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49(3):389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Ma GX, Shive S. A comparative analysis of perceived risks and substance abuse among ethnic groups. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(3):361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R, Kajdasz DK, Herron J, Anton RF, Brady KT. A double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient trial of pergolide for cocaine dependence. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60(2):161–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand G, Waller M, Carey SM. Kalamazoo County Adult Drug Treatment Court: Outcome and cost evaluation 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Lee PA. Are judicial status hearings a “key component” of drug court? Six and twelve months outcomes. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2005;79(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Dugosh KL, Lee PA, Benasutti KM. Adapting judicial supervision to the risk level of drug offenders: discharge and 6-month outcomes from a prospective matching study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Lee PA, Dugosh KL, Benasutti KM. Matching Judicial Supervision to Clients’ Risk Status in Drug Court. Crime Delinq. 2006;52(1):52–76. doi: 10.1177/0011128705281746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele GM, Carpenter KM, Cockerham MS, Trautman KD, Blaine J, Hasin DS. Substance Dependence Severity Scale: reliability and validity for ICD-10 substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(4):603–12. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J. The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2001;21(4):193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ, Karberg JC. Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisoners, 2004. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Peters RH, Haas AL, Murrin MR. Predictors of retention and arrest in drug courts. National Drug Court Institute Review. 1999;2:33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Platt JJ. Vocational rehabilitation of drug abusers. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):416–433. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling J, Oliveto A, Petry N, Sofuoglu M, Gonsai K, Gonzalez G, Martell B, Kosten TR. Six-month trial of bupropion with contingency management for cocaine dependence in a methadone-maintained population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):219–228. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Casadonte P, Baker S, Sanfilipo M, Braunstein D, Hitzemann R, Montgomery A, Majewska D, Robinson J, Rotrosen J. A placebo-controlled screening trial of olanzapine, valproate, and coenzyme Q10/L-carnitine for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100(Suppl 1):43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman J, Townsend W, Bhati AS. Recidivism rates for drug court graduates: Nationally based estimates. Washington DC: The Urban Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Accessed 3/30/09]. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/reports.htm#2k6. [Google Scholar]

- Saum CA, Scarpitti FR, Robbins CA. Violent offenders in drug court. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31(1):107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Averill P, Stotts AL, Moeller FG, Rhoades HM, Grabowski J. Fluoxetine treatment of cocaine-dependent patients with major depressive disorder. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63(3):207–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Mooney ME, Moeller FG, Stotts AL, Green C, Grabowski J. Levodopa pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: Choosing the optimal behavioral therapy platform. Drug and alcohol dependence Netherlands, Elsevier Science. 2008;94:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechrest DK, Schicor D. Determinants of graduation from a day treatment drug court in California: A preliminary study. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31(1):129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sung HE, Belenko S. Failure after success: Correlates of recidivism among individuals who successfully completed coerced drug treatment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation US, Haworth Press. 2005;42:75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sung HE, Belenko S, Feng L, Tabachnick C. Predicting treatment noncompliance among criminal justice-mandated clients: A theoretical and empirical exploration. Journal of substance abuse treatment Netherlands, Elsevier Science. 2004;26:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-seeking for depression by Black and White Americans. Social science & medicine. 1987;24(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S. Race of counselor, client sex, cultural mistrust level, and premature termination from counseling among Black clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31(3):371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy K, Babuscio T, Nich C, Kiluk B, Carroll KM, Petry NM, Rounsaville BJ. Contingency Management to Reduce Substance Use in Individuals Who are Homeless with Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disorders. 2007;33(2):253–258. doi: 10.1080/00952990601174931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. What can long-term follow-up teach us about relapse and prevention of relapse in addiction? British journal of addiction. 1988;83(10):1147–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]