Abstract

Studies of person perception (people's impressions and beliefs about others) have developed important concepts and methods that can be used to help improve the assessment of personality disorders. They may also inspire advances in our knowledge of the nature and origins of these conditions. Information collected from peers and other types of informants is reliable and provides a perspective that often differs substantially from that obtained using questionnaires and interviews. For some purposes, this information is quite useful. Much remains to be learned about the incremental validity (and potential biases) associated with data from various kinds of informants.

Keywords: assessment, personality disorders, person perception, self-knowledge

Personality disorders are enduring patterns of behavior and emotion that bring a person into repeated conflict with others and prevent the person from performing expected social and occupational roles. People with personality disorders often make their own interpersonal problems worse because they are rigid and inflexible, unable to adapt to social challenges. Nevertheless, they may not see themselves as being disturbed, attributing their problems instead to the behavior of other people. Many forms of personality disorder, such as paranoid, narcissistic, antisocial, and histrionic personality disorder, are defined primarily in terms of problems that people create for others rather than in terms of the person's own subjective distress (Westen & Heim, 2003).

Studies of person perception (how people perceive other people, especially their personality characteristics) raise challenging issues and interesting opportunities for the assessment of personality disorders (Clark, 2007; Widiger & Samuel, 2005). There is, at best, only a modest correlation between individuals' descriptions of themselves and descriptions of them provided by others (Biesanz, West, & Millevoi, 2007; Watson, Hubbard, & Weise, 2000). It is therefore surprising that most knowledge of personality disorders is based on evidence obtained from self-report measures (questionnaires and diagnostic interviews). The person is asked to answer questions such as “Are you stubborn and set in your ways?”, “Do you behave in an arrogant and haughty way?”, and “Is it easy for you to lie if it serves your purpose?” Data from these instruments should be supplemented by other sources of information regarding personality, such as informant reports, observations of behavior in structured situations, and life-outcome data. The goal of this article is to describe evidence about the relations among, and relative merits of, assessments of personality disorders based on self-report measures and information provided by informants who know that person well.

Our research group has studied interpersonal perception of pathological personality traits in two large samples of young adults—approximately 2,000 military recruits and 1,700 college freshmen (Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2006). The participants were identified and tested in groups. Military training groups included between 27 and 53 recruits, and college dormitory groups included between 12 and 22 students. Each group was composed of previously unacquainted young adults who had many opportunities to observe each other's behavior after living together in close proximity for a standard period of time (6 weeks for the recruits and 5 to 7 months for the students). Although these were not clinical samples of patients being treated for mental disorders, they did include people with significant personality problems. Diagnostic interviews indicated that, consistent with data from other community samples, approximately 10% of our participants qualified for a diagnosis of at least one personality disorder.

All participants in each group completed self-report questionnaires, and they also nominated members of their group who exhibited specific features of personality disorders. Everyone served as both a judge and a possible target. Serving as a judge for each specific item, the participant rated only those people whom he or she viewed as showing the characteristics in question. Exactly the same items were included in both the self-report and peer nomination scales. All were lay translations of specific diagnostic features used to define personality disorders in the official psychiatric classification system. Examples include: “Is stuck up or `high and mighty'” (narcissistic PD), “Needs to do such a perfect job that nothing ever gets finished” (obsessive-compulsive PD), and “Has no close friends, other than family members” (schizoid PD).

This design allowed us to examine four issues regarding interpersonal perception: consensus, self–other agreement, accuracy, and metaperception (Funder, 1999; Kenny, 2004). Consensus is concerned with whether different judges agree in their perceptions of the target person's personality. Self–other agreement involves the extent to which people view themselves in the same ways they are described by other people. Accuracy refers to the validity of self- and other judgments. In other words, is either source of information related in a meaningful way to outcomes in the person's life, such as social adjustment or occupational impairment? Metaperception describes the extent to which people are aware of the impressions that other people have of them. In other words, regardless of my own description of myself, am I aware of what others think of me?

CONSENSUS AMONG PEERS IS MODEST

Studies of person perception report acceptable levels of consensus among laypeople when making judgments of normal personality traits, especially when ratings are aggregated across a large number of judges (Funder, 1999; Vazire, 2006). Data from our study indicate modest consensus among peers in judgments of other people's personality pathology. Reliability of composite peer-based scores—averaged across a number of judges—was good (Clifton, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2005; Thomas, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2003). Their judgments were presumably based on opportunities they had had to observe each other's behavior, often in challenging situations, over a period of several weeks. Peers developed meaningful perspectives on the personality problems of other group members, and they tended to agree about which members exhibited those problems.

Previous studies indicate that the level of consensus among judges varies as a function of many considerations, such as the extent of acquaintance between judges and the target person (Letzring, Wells, & Funder, 2006). Many decisions about personality disorders, including those made by clinicians, as well as those made by family members, friends, and the peers in our studies, are based on thoughtful deliberation following extended observations of inconsistent, puzzling, annoying, and occasionally disturbing behaviors. It is also clear, however, that some personality judgments about other people are formed quickly and without conscious effort or reason (Ambady, Bernieri, & Richeson, 2000).

Data from our lab suggest that, on the basis of minimal information, observers can form reliable impressions of people who qualify for diagnoses of various types of personality disorder. Untrained raters watched only the first 30 seconds of videotaped interviews with target persons from our study. Based only on these thin slices of behavior, the raters generated reliable judgments regarding broad personality traits using the Five Factor Model, a widely accepted system for describing personality. Higher levels of consensus were found for extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness, while lower agreement was found for neuroticism. The judges' ratings were also accurate in some ways. People who were otherwise unacquainted with our target persons detected the low extraversion of individuals with features of schizoid and avoidant personality disorders and the high extraversion of individuals with histrionic personality features. They were also reliable in rating specific features of personality disorders (such as “Is stuck up or `high and mighty'” with regard to narcissistic personality disorder), and these judgments were significantly correlated with more extensive diagnostic information collected from the persons and from their peers (Friedman, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2007).

Perceptions of pathological personality traits also influenced the extent to which the thin-slice raters liked the people they had watched. They were less interested in meeting people with schizoid and avoidant personality traits and were more interested in getting to know people who exhibited traits associated with histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. These patterns suggest possible mechanisms that may maintain or exacerbate personality difficulties. To the extent that people who are avoidant create a negative first impression, they may become even more anxious about their interactions with other people. On the other hand, histrionic and narcissistic behaviors may be perpetuated by the way in which they attract others, at least temporarily. These traits may not become interpersonally disruptive until relationships become more intimate.

SELF-OTHER AGREEMENT IS ALSO MODEST

One primary issue in our study involved the correspondence between self-report and peer nominations for characteristic features of personality disorders. Table 1 presents results from our sample of military recruits using scores based on a factor analysis of self-report and peer-nomination data (Thomas et al., 2003). The factors correspond closely to diagnostic categories for personality disorders: histrionic-narcissistic, dependent-avoidant, detachment (similar to schizoid), aggression-mistrust (similar to paranoia), antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, and schizotypal (an enduring pattern of discomfort with other people coupled with peculiar thinking and behavior). The data show a modest level of convergent and discriminant validity (i.e., measures of the same concept are more highly correlated with each other than measures of different concepts) for peer- and self-perception on these particular traits. Within-trait cross-method correlations appear on the diagonal. In every case, the within-trait cross-method correlation (e.g., between self-report for antisocial personality features and peer nominations for antisocial personality features) was higher than any of the cross-trait correlations. The highest correlations fell on the diagonal, but they were also modest in size, suggesting disagreement between the ways in which people described themselves and the ways in which they were described by their peers. These data and the results of studies from other labs suggest that self-reports provide a limited view of personality problems (Furr, Dougherty, Marsh, & Matthias, 2007; Miller, Pilkonis, & Clifton, 2005).

TABLE 1.

Correlations Between Peer and Self-Report Scores for Personality Pathology Factors in a Military Sample

| Peer |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | HN | DA | DET | AM | ANT | OC | STY |

| HN | .22 | −.09 | .02 | −.07 | .01 | −.07 | .07 |

| DA | −.18 | .30 | −.07 | −.08 | −.01 | −.07 | .05 |

| DET | −.08 | −.03 | .21 | .03 | .19 | .03 | −.07 |

| AM | −.07 | .10 | −.04 | .29 | .10 | .08 | −.08 |

| ANT | −.17 | .08 | .03 | .07 | .30 | .12 | −.04 |

| OC | −.08 | .00 | .03 | .08 | .05 | .27 | −.02 |

| STY | .07 | −.01 | −.01 | −.07 | .03 | −.02 | .24 |

Note. HN = Histrionic/Narcissistic; DA = Dependent/Avoidant; DET = Detachment; AM = Aggression/Mistrust; ANT = Antisocial; OC = Obsessive-Compulsive; STY = Schizotypal.

Correlations can vary from 0 to 1.0, with 0 meaning that there is no relationship between two variables and 1.0 meaning that there is a perfect relationship. Positive correlations indicate that as one variable increases, the other also increases. Correlations between .10 and .30 are often considered to be small, and correlations between .30 and .50 are interpreted as being medium in size.

Reprinted from “Factorial Structure of Pathological Personality Traits as Evaluated by Peers,” by C. Thomas, E. Turkheimer, & T.F. Oltmanns, 2003, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, p. 8. Copyright 2003, American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

The level of agreement between self-report and peer report is fairly good and is actually no better or worse than the level of agreement between any two specific peers. One advantage of informant reports is that there are many possible sources. Composite scores, averaged across several friends, family members, or peers, are likely to be more reliable than a single self-report score. But the most important issue is incremental validity: Do peer reports add important information beyond that which is provided in self-report measures?

METAPERCEPTIONS ARE NOT BASED EXCLUSIVELY ON SELF-PERCEPTIONS

The fact that people do not always agree with others' perceptions of them does not necessarily imply that they are unaware of what others think. They may simply hold a different view. The literature on metaperception for normal personality traits suggests that people do, in fact, have some accurate, generalized knowledge of what others think of them (Kenny, 1994).

Participants in our study were asked to anticipate the ways in which most other members of their group would describe them. These “expected peer” scores were highly correlated with the participants' own descriptions of themselves (i.e., “What are you really like?”). People believe that others share the same view that they hold of their own personality characteristics. On the other hand, we also found that expected peer scores predicted some variability in peer report over and above self-report for all of the different forms of personality disorder (Oltmanns, Gleason, Klonsky, & Turkheimer, 2005). This finding suggests that people do have at least some small amount of incremental knowledge regarding how they are viewed by others. They are sometimes aware of the fact that other people think they have personality problems, but they usually don't tell you about it unless you ask them.

INFORMANT REPORTS ARE ACCURATE FOR SOME PROBLEMS

Perhaps the most important issue in the field of interpersonal perception involves accuracy, or validity. Disagreement between sources of information (self and informant) does not suggest that one kind of measure is more valid than the other. The most important question is, which source of data is most useful, and for what purpose? One relevant study examined self- and informant reports of personality disorders in a follow-up study with depressed patients (Klein, 2003). Both self-report and informant reports regarding personality disorders were associated with a worse outcome in terms of depressed symptoms and global functioning. However, informants' reports of personality pathology were the most useful predictor of future social impairment.

Similar results have been found in our research with regard to job success following successful completion of basic military training (Fiedler, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2004). All of the recruits had enlisted to serve for a period of 4 years. At the time of follow-up, we divided the recruits into two groups: (a) those still engaged in active duty employment, and (b) those given an early discharge from the military. Early discharge is typically granted by a superior officer on an involuntary basis, and is most often justified by repeated disciplinary problems, serious interpersonal difficulties, or a poor performance record.

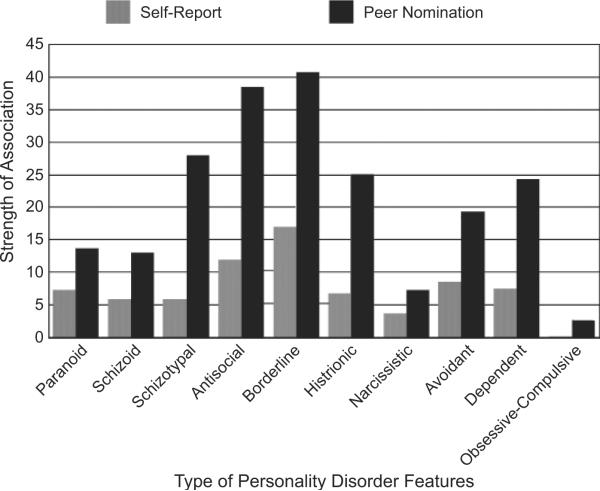

We conducted a survival analysis of “time to failure”—that is, an analysis of the predictors of how much time it took recruits to be discharged early. We used standard rank-based procedures (using ordinal as opposed to interval data) to estimate the univariate relations between self- and peer-report of the 10 personality disorders and early discharge from the military. Results are shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the magnitude of the relation between each disorder and risk for discharge. For all of the disorders except obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, higher scores were associated with greater risk of early discharge. The figure shows that in general, peer reports of personality disorders were better predictors than self-reports were. When we combined the self-report and peer-based information, using them together to identify recruits who were discharged early from the military, the best predictor variables were peer scores for antisocial and borderline personality disorders.

Fig. 1.

Relative strength of self-report and peer report in predicting early separation from military service, for 10 types of personality-disorder features. (Strength of association between self- and peer-nominated traits and risk for early termination is expressed as a chi-square test of the log-rank Wilcoxon.)

These results point to several general conclusions. Both self-report and peer nominations were able to identify meaningful connections between personality problems and adjustment to military life. Self-report measures emphasized features that might be described as internalizing problems (subjective distress and self-harm) while the peer-report data emphasized externalizing problems (antisocial traits). Considered together, the peer-nomination scores were more effective than the self-report scales were in predicting occupational outcome. The relative merits of self- and peer reports probably differ with regard to the measure of functioning or outcome that is being predicted, and future research ought to focus on those comparisons across a wide range of constructs.

SUMMARY AND ISSUES FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Informants can provide reliable and valid information about an individual that is largely independent of that obtained from the person's own self-report. Correlations between self-report and informant reports are consistently modest, and the independent information provided by informants tells us something important about personality problems. This conclusion is consistent with the more general observation that personality disorders are frequently defined and experienced in terms of interpersonal conflict and problems in person perception. Although most investigators rely on self-report measures to assess personality disorders, a more complete description of the person would be obtained by also considering data from informants. The most comprehensive approach would be one that assembled and integrated data from many different people, including the self, thus reflecting the widest possible range of impressions of the target person's behavior in different contexts.

Of course, it is difficult to collect data from a large number of people who know the target person, and it is seldom possible to contact people who are not selected by (and may not like) the target person. Therefore, to whatever extent they are able to gather data from informants, most researchers will rely on a small number of informants chosen by the subject. Future studies need to investigate these issues. How many informants are needed in order to provide a useful perspective that complements the person's own description of himself or herself? What kind of bias is introduced by various kinds of self-selected informants (parents, spouses, friends)? How are data that these people provide different from those that might be obtained from informants who are not selected by the target person? And perhaps most important, how does the validity of informant reports compare to that of self-report measures when a broader range of outcome measures is considered?

Longitudinal studies of person perception in the context of specific relationships will also be important. Thin-slice studies suggest that people with different kinds of personality problems can create marked impressions (both positive and negative) on others at the outset of a relationship. It will be interesting to learn how these impressions affect the progression of the relationship and how such perceptions may change over time.

Recommended Readings.

Achenbach, T.M., Krukowski, R.A., Dumenci, L., & Ivanova, M.Y. (2005). Assessment of adult psychopathology: Meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 361–382. A thorough and critical review of issues regarding limitations of self-report instruments for the purpose of measuring psychopathology, across many different types of mental disorder.

Klonsky, E.D., Oltmanns, T.F., & Turkheimer, E. (2002). Informant reports of personality disorder: Relation to self-reports and future research directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 300–311. A summary of research evidence from studies that have specifically compared self- and informant reports of personality disorders regarding the same target persons.

Wilson, T.D., & Dunn, E.W. (2004). Self knowledge: Its limits, value, and potential for improvement. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 493–518. A comprehensive summary of evidence regarding the ability of individuals to understand what others think of them.

REFERENCES

- Ambady N, Bernieri FJ, Richeson JA. Toward a histology of social behavior: Judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the behavioral stream. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2000;32:201–271. [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, West SG, Millevoi A. What do you learn about someone over time? The relationship between length of acquaintance and consensus and self-other agreement in judgments of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:119–135. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton A, Turkheimer E, Oltmanns TF. Self and peer perspectives on pathological personality traits and interpersonal problems. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:123–131. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler ER, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Traits associated with personality disorders and adjustment to military life: Predictive validity of self and peer reports. Military Medicine. 2004;169:207–211. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JNW, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Interpersonal perception and personality disorders: Utilization of a thin slice approach. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:667–688. [Google Scholar]

- Funder DC. Personality judgment: A realistic approach to person perception. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Furr RM, Dougherty DM, Marsh DM, Mathias DW. Personality judgment and personality pathology: Self-other agreement in adolescents with conduct disorder. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:629–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis. Guilford; New York: 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. PERSON: A general model of interpersonal perception. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:265–280. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN. Patients' versus informants' reports of personality disorders in predicting 7 1/2-year outcome in outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:216–222. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letzring TD, Wells SM, Funder DC. Information quantity and quality affect the realistic accuracy of personality judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:111–123. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Pilkonis PA, Clifton A. Self- and other-reports of traits from the five-factor model: Relations to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:400–419. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Gleason MEJ, Klonsky ED, Turkheimer E. Meta-perception for pathological personality traits: Do we know when others think that we are difficult? Consciousness and Cognition. 2005;14:739–751. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Perceptions of self and others regarding pathological personality traits. In: Krueger RF, Tackett JL, editors. Personality and psychopathology. Guilford; New York: 2006. pp. 71–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Turkheimer E, Oltmanns TF. Factorial structure of pathological personality traits as evaluated by peers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire S. Informant reports: A cheap, fast, and easy method for personality assessment. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Hubbard B, Weise D. Self-other agreement in personality and affectivity: The role of acquaintanceship, trait visibility, and assumed similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:546–558. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Heim AK. Disturbances of self and identity in personality disorders. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of self and identity. 2003. pp. 643–664. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Samuel DB. Evidence-based assessment of personality disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:278–287. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]