Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether minor depression differs from major depression in clinically relevant ways.

Method:

Structured interviews, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) scores, and physicians' treatment recommendations were obtained systematically from 1,458 admissions to an outpatient teaching clinic during a 5-year period from 1981 to 1986. Of these, 1,002 (69%) satisfied inclusive DSM-III lifetime criteria for a major depressive episode. Of the 456 outpatients who did not formally satisfy criteria for a major depressive episode, 79 (17%) acknowledged significant depressive symptoms that caused major interference in their lives. These 79 outpatients were classified as suffering from minor depression.

Results:

No gender or other sociodemographic differences were found between the 2 outpatient groups except that the minor depression group had achieved a higher level of education. No differences were found for a family history of psychiatric illness among first-degree relatives, including a family history of depression. Ratings of childhood unhappiness/problems did not distinguish the 2 groups. The major depression group endorsed more lifetime depressive symptoms and met criteria for more co-occurring disorders, principally mania and the anxiety disorders. The group with major depression reported poorer psychosocial functioning when first seen and more past psychiatric treatment. The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) profile was significantly elevated in both groups. The type of initial treatment recommended did not distinguish the major from minor depression groups.

Conclusions:

Minor depression seems to represent the same illness as major depression but in a less severe form that, nevertheless, requires the attention of professional health care providers in both primary and specialized care settings.

Many individuals who seek help from mental health professionals suffer from significant depressive symptoms but do not formally satisfy the DSM inclusive criteria for a diagnosis of major depression. In the DSM-III1 and DSM-IV,2 the diagnostic option for individuals suffering from subthreshold or subsyndromal depression is “NOS” or “depression, not otherwise specified.” However, the “depression, NOS” designation covers other subthreshold conditions including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, recurrent brief depressive disorder, postpsychotic depressive disorder of schizophrenia, and major depressive episode superimposed on a delusional disorder. Many clinicians find the NOS designation unsatisfactory, and some third-party payers will not cover a NOS diagnosis. Several clinicians have proposed the adoption of a unique term and specific diagnostic code for subthreshold conditions, such as minor depression.

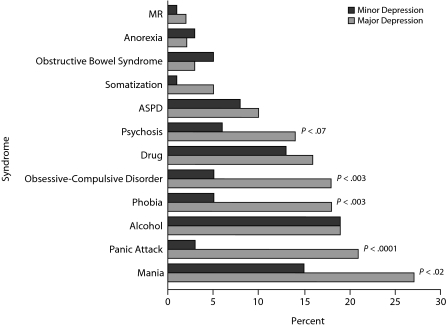

Figure 1.

Psychiatric Comorbidity in the Major and Minor Depression Groupsa,b

aNumber of positive syndromes: mean = 0.8 for minor depression and mean = 1.5 for major depression.

bExcluding depression, p < .001.

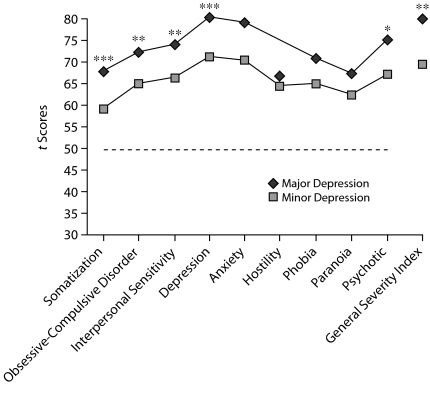

Figure 2.

Major Versus Minor Depression for Male Patientsa

aSCL-90-R t scores using norms from nonpatient males (mean = 50, SD = 10).

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

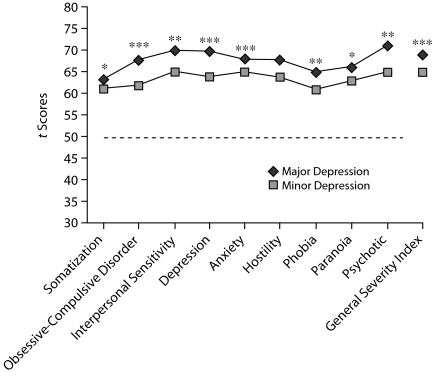

Figure 3.

Major Versus Minor Depression for Female Patientsa

aSCL-90-R t scores using norms from nonpatient females (mean = 50, SD = 10).

*P < .05.

**P < .001.

***P < .0001.

Minor depression is one of the proposed, but not currently accepted, subthreshold conditions described in Appendix B of the DSM-IV.2 It is defined as the presence of at least 2, but fewer than 5, depressive symptoms (1 symptom must be either depressed mood or loss of interest) during the same 2-week period, with no history of a major depressive episode or dysthymia. In contrast, major depression is defined in both the DSM-III and DSM-IV as the presence of either depressed mood or loss of interest or irritability (if 18 years or younger) with 5 or more depressive symptoms, lasting at least 2 weeks, with no history of a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode. A criterion for both major and minor depression includes the requirement that depressive symptoms significantly impair the individual's ability to function.

Regier and colleagues3,4 have argued that diagnoses in the DSM-IV should be restricted to those cases that are in need of treatment. However, Kessler et al5 suggest that mild cases of mental illness should be retained in the DSM, regardless of an immediate treatment requirement, because they reflect a significant number of undiagnosed but distressed individuals. The controversy between Kessler et al and Regier et al is focused on the amount of suffering, the degree of impairment, and the need for treatment in so-called “subthreshold” or “minor” cases.3–6

Clinical Points

♦ Minor depression seems to be a milder presentation on a continuum of severity of the same illness called major depression and is highly predictive of the latter.

♦ Primary care settings are commonly the first point of contact for depressed patients where monitoring and periodic reassessment of depressive symptoms can be done.

♦ When symptoms of minor depression persist or worsen or when there is increasing functional impairment, antidepressant medication should be considered.

The lifetime prevalence of minor depression ranges from a low of 4.5% to a high of 10.9%,7 largely because the definitions for subthreshold depression vary considerably. Pincus et al8 conclude that the definitions of subthreshold in mental health are extremely varied and inconsistent. They suggest that explicit definitional standards will need to be established before the issues surrounding subthreshold mental illness can be resolved.8 In another major review, Sherbourne et al9 concluded that “subthreshold depression appeared to be a variant form of affective disorder and was treated as such in the mental health specialty sector but not in the general medical sector.”(p1777) Rapaport et al10 found that minor depression may occur “either independently of a lifetime history of major depressive disorder or as a stage of illness in the course of recurrent unipolar depressive disorder.”(p637)

In a more recent prospective study that involved a 15-year follow-up, Fogel et al11 found that minor depression was a strong predictor of major depression. In the primary care setting, in which patients with depressive symptoms are commonly seen, Wagner et al12 found that patients with minor depression were substantially more impaired, including in health and functional status, than those without depressive symptoms. In addition, they were qualitatively similar to patients with major depression.

We ask whether minor depression can be considered a distinct clinical entity from major depression or part of a symptom severity continuum. We applied the Washington University Model of Clinical Validity13–15 whenever possible to address this issue. This model states that, when the pathophysiology and etiology of a clinical condition are unknown, then indirect methods can be applied to “validate” that clinical condition. Thus, a clinical condition is more likely to be an independent entity when it differs from other similar conditions according to family history of the illness, onset and course of the illness, and treatment response. Clinical measures such as these were used to compare subjects assigned to major and minor depression groups.

METHOD

Procedure and Instruments

Over a 5-year period from 1981 to 1986, the majority of new admissions (96.7%) to the outpatient psychiatry service at the University of Kansas Medical Center (Kansas City) were included in the study. Before seeing the clinic psychiatrist, they were administered the structured Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview (PDI),16,17 the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R),18 and a Psychosocial Questionnaire that included a family history form. A total of 1,458 patients who received the structured diagnostic interview served as the subjects in this study.

The PDI is a criterion-based instrument based upon the descriptive, syndromatic model of psychiatric diagnosis. Representing an elaboration and refinement of the diagnostic system proposed by Feighner et al,19 the version administered to these patients in the early and mid 1980s was modified for compatibility with DSM-III criteria. The face-to-face interview was developed to determine whether an individual currently meets or has ever met lifetime inclusive diagnostic criteria for any of 15 major psychiatric disorders including major depression, mania, schizophrenia (psychosis), alcoholism, drug abuse, and others. Extensive tests of the instrument's reliability and validity can be found in its manual and elsewhere.20,21 Interviewers were clinic professional staff and individually supervised third-year medical students. The PDI and all other instruments described here were part of the routine clinic procedures.

The SCL-90-R is a 90-item, self-administered, psychiatric symptom checklist. Subjects rated each symptom experienced in the past week on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The instrument yields 9 subscales and a General Severity Index that reflects current level of emotional distress.

The paper-and-pencil Psychosocial Questionnaire reviewed sociodemographic characteristics, various self-rating scales of functioning, family history of psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives, and past treatments received. Self-report of functioning in 7 life areas during the 6 months prior to treatment were rated on a 4-point scale and were included in this instrument. Data for this psychosocial questionnaire were available for only 76% of the subjects.

Subjects

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the total sample. The mean (SD) age of the 1,458 subjects was 38.1(14.31) years, 64% were female, and 78.5% were white, 15.5% were black, and 6% reported other racial heritage.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients With Major or Minor Depression

| Items | Minor Depression (n = 79)a | Major Depression (n = 1,002)a | Total (n = 1,081)a |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.6 (14.26) | 37.9 (13.85) | 39.25 (14.05) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (28) | 335 (33) | 357 (33) |

| Female | 57 (72) | 667 (67) | 724 (67) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 51 (75) | 602 (80) | 653 (60) |

| Black | 13 (19) | 105 (14) | 118 (11) |

| Other | 4 (6) | 37 (5) | 41 (4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Never | 15 (22) | 203 (30) | 218 (20) |

| Married | 32 (47) | 310 (41) | 342 (32) |

| Divorced/separated/widow | 21 (31) | 245 (32) | 266 (25) |

| Education, n (%)b | |||

| < High school | 6 (9) | 139 (18) | 145 (13) |

| GED/high school | 14 (21) | 197 (26) | 211 (20) |

| > High school | 48 (71) | 420 (56) | 468 (43) |

| Employment status (past mo), n (%) | |||

| Full-time | 28 (41) | 310 (41) | 438 (41) |

| Part-time | 8 (12) | 63 (12) | 71 (6) |

| Unemployed | 32 (47) | 379 (50) | 411 (38) |

| Months employed (past 6 mo), mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.85) | 2.8 (2.70) | |

Data were missing for some categories.

P < .05.

Formation of the Groups

Of the total 1,458 patients, 1,002 or 68.7% fulfilled inclusive DSM-III criteria for major depression and 79 or 17.3% for minor depression. The major depression group (n = 1,002) comprised patients who met lifetime diagnostic criteria for at least 1 major depressive episode on the PDI. The minimum duration requirement for depressive symptoms was 1 month as stipulated in the DSM-III instead of 2 weeks as stipulated in the DSM-IV. The minor depression group (n = 79) was defined according to the research criteria proposed in the DSM-IV for minor depressive disorder. Thus, patients having reported dysphoric mood or anhedonia with significant life interference and at least 2 but no more than 4 depressive symptoms were included in the minor depression group. Subjects in the minor depression group did not have to meet the 1-month duration criteria required for subjects in the major depression group.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were performed to compare major and minor depression groups for categorical data. Wilcoxon tests were used to compare ordinal data, and group means were compared using F tests calculated with the general linear model procedure. All statistical analyses were completed using the SAS Software System, version 8 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics

As noted in there were no significant differences found between the major and minor depression groups across age, gender, race, marital status, and employment variables. However, the highest level of education achieved was significantly lower in the major depression group; only 56% in the major depression group finished high school compared to 71% in the minor depression group (P = .04).

Childhood Ratings

Retrospective ratings reported by subjects of personal happiness and problems in childhood, including ability to make friends and dating, were similar in both groups. For example, 11% in the major depression group compared to 19% in the minor depression group reported having been unusually happy as children; 14% in the major depression group reported that it was very hard to make friends during teen years compared to 11% in the minor depression group.

Family History

A family history of psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives did not distinguish the 2 groups. Included were a family history of depression, mania, panic attack, sustained psychosis, alcoholism, drug abuse, and attempted or completed suicide. Thirty-six percent of subjects in the major depression group reported a family history of depression versus 25% in the minor depression group (P < .001).

Psychiatric Comorbidity

As seen in significantly more subjects in the major depression group satisfied the DSM-III inclusive lifetime criteria for panic attack, mania, phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder than in the minor depression group. Even when the depression syndrome is excluded, the major depression group had a mean of 1.5 positive comorbid syndromes compared to a mean of 0.8 in the minor depression group, a highly significant difference (P = .0001).

Depressive Symptoms

Twenty-six lifetime symptoms of depression were reviewed with each subject. Each one of these depressive symptoms was endorsed significantly more often in the major depression group than in the minor depression group, as expected. For example, reports of trouble sleeping, loss of energy, thoughts about death or dying, and attempted suicide were significantly higher in the major depression group. The total number of lifetime depressive symptoms was significantly higher in the major depression group. The mean (SD) number of lifetime depressive symptoms in the major depression group was 17.0 (4.55) versus 10.2 (6.44) in the minor depression group. This difference was highly significant (F1,1080 = 152.55; P = .0001).

Psychosocial Functioning

Subjects in the major depression group reported significantly more problems in daily life during the 6-month period prior to clinical evaluation than did the minor depression group (Table 2). These problems included getting along with others, managing finances, ability to relax, happiness ratings, and stress ratings. For example, the major depression group reported more difficulty managing their finances (P = .0005), with 23% reporting a very big problem versus only 5% in the minor depression group. Fifty-five percent of subjects in the major depression group versus 36% in the minor depression group reported high levels of stress. A summary variable (sum of the rank scores) of the 7 items evaluating daily life problems revealed a mean (SD) of 2.8 (0.68) for the major depression group and 2.3 (0.58) for the minor depression group, a significant difference (F1,783 = 25.18; P = .0001).

Table 2.

| Depression (N = 1,081) |

|||

| Item | Minor (n = 66) | Major (n = 742) | Pde |

| Getting along with people | |||

| No problem | 29 (44) | 208 (28) | .009 |

| Little problem | 20 (30) | 286 (39) | |

| Pretty big problem | 15 (23) | 150 (20) | |

| Very big problem | 2 (3) | 98 (13) | |

| Getting along with family | |||

| No problem | 25 (38) | 190 (26) | .07 (.02) |

| Little problem | 28 (42) | 307 (42) | |

| Pretty big problem | 7 (11) | 155 (21) | |

| Very big problem | 6 (9) | 86 (12) | |

| Managing financial affairs | |||

| No problem | 26 (39) | 162 (22) | .0005 |

| Little problem | 22 (33) | 239 (32) | |

| Pretty big problem | 15 (23) | 169 (23) | |

| Very big problem | 3 (5) | 173 (23) | |

| Ability to relax /enjoy | |||

| No problem | 8 (12) | 56 (8) | .003 |

| Little problem | 27 (41) | 205 (28) | |

| Pretty big problem | 23 (35) | 236 (32) | |

| Very big problem | 8 (12) | 243 (33) | |

| Satisfied with self | |||

| Very satisfied | 7 (11) | 43 (6) | .0001 |

| Pretty satisfied | 23 (35) | 111(15) | |

| Not very satisfied | 26 (39) | 320 (44) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 10 (15) | 259 (35) | |

| Happiness rating | |||

| Very happy | 4 (6) | 13 (2) | .0001 |

| Pretty happy | 22 (33) | 106 (14) | |

| Little unhappy | 23 (35) | 245 (33) | |

| Very unhappy | 17 (26) | 372 (52) | |

| Tension and stress | |||

| Very little stress | 4 (6) | 30 (4) | .01 (.002) |

| Some stress | 22 (33) | 150 (20) | |

| Pretty much stress | 16 (24) | 149 (20) | |

| A lot of stress | 24 (36) | 409 (55) | |

Data are presented as n (%).

Data were missing for some categories.

During the past 6 months.

P values based on the χ2 test; Wilcoxon tests were also performed and differed as indicated in parentheses.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Past Utilization of Psychiatric Services

Over two thirds of the major depression group, compared to one third of the minor depression group, reported using previous psychiatric services, including treatment in the past 6 months or over their lifetime (P < .001). Thirty-nine percent of subjects in the major depression group had been hospitalized for psychiatric problems versus 21% in the minor depression group, also a significant difference (P = .05). However, no differences were noted for age at first psychiatric hospitalization, the total number of psychiatric hospitalizations, or the response to medications in the past 6 months.

Symptomatic Distress Reported at Time of Evaluation

Results from the SCL-90-R18 are shown in for males and females separately because SCL-90-R norms differ widely as a function of gender. Raw scores, calculated for each of the 2 groups for the 9 Primary Symptom Dimensions and the single General Severity Index summary score, were converted into standardized t scores based on nonpatient male and female norms. The use of nonpatient norms as the point of reference provides the opportunity to examine the relative differences between the 2 groups on the basis of normative nonpsychiatric populations.

The raw scores for all of the primary symptom dimensions and the General Severity Index (an average of the elevation for all 90 symptoms ranging from 0.00 to 4.00) among males in the major depression group exceeded those for males in the minor depression group. In 6 of 10 comparisons, these differences were significant at P < .05 (somatization, obsessive-compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, psychosis, and General Severity Index). When the raw scores were transformed to t scores, males in the major depression group also scored higher than males in the minor depression group. More importantly, as seen in the scores for males in the minor depression group, compared to nonpsychiatric males, were approximately 1 standard deviation higher. Clearly, males in the minor depression group experienced considerable symptomatic distress compared to nonpatient males.

As shown in the same pattern was observed for female patients. Female patients with major depression scored significantly higher than those with minor depression on 9 of 10 SCL-90-R symptom scales and on the General Severity Index (P < .05). Like the males, female patients with minor depression produced T scores indicating very high levels of symptomatic distress and discomfort when compared to nonpatient females in the normative groups.

Initial Treatment Recommendations

The type of treatment recommended by the clinicians at the initial visit did not distinguish the 2 clinical groups (Table 3). An equal percentage in both groups was prescribed a psychotropic medication. Sixty-five percent in the major depression group compared to 54% in the minor depression group were prescribed an antidepressant medication. An equal percentage of patients in both groups were prescribed anxiolytic medications. Psychotherapy was recommended for 16% of subjects in the major depression group compared to 23% in the minor depression group, a difference that is not significant.

Table 3.

| Medication Class | Minor (n = 57) | Major (n = 791) |

| Antidepressants | 54 (95) | 65 (8) |

| Anticonvulsants | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Lithium | 12 (21) | 9 (1) |

| Antipsychotics | 11 (19) | 14 (2) |

| Anxiolytics | 25 (43) | 25 (3) |

| Others | 16 (28) | 16 (2) |

| Psychotherapy | 23 (40) | 16 (2) |

All data are presented as n (%).

Information on medication was not available for all subjects.

No significant differences were found.

DISCUSSION

This study found many similarities between minor and major depression along important clinical dimensions that included family history of psychiatric illness, childhood ratings, and treatment history. The short-term response to medication within the month before coming to the clinic was almost identical for both groups. Psychotropic medication was prescribed equally often to both groups after their initial evaluation.

Differences found between major and minor depression included greater psychiatric distress and poorer psychosocial functioning in patients who met criteria for major depression. The amount of symptomatic distress reported in the minor depression group for both male and female patients was much greater than that of the normative population of males and females. The major depression group consistently reported more problems in psychosocial functioning over several life areas: getting along with others, managing financial affairs, self-satisfaction, happiness, tension, and stress. These similarities and differences found between major and minor depression supported the hypothesis that the 2 groups do not reflect separate clinical entities, but, rather, represent differences in severity of the same illness.

These results are consistent with Judd et al,22 who suggested that “depressive symptoms, minor depression/dysthymia, and MDD represent a continuum of depressive symptom severity in unipolar MDD each level of which is associated with significant stepwise increment in psychosocial disability.”(p375) Our conclusion is also supported by other authors11,23 who have conducted long-term, prospective studies that have demonstrated that symptom severity in depressive patients fluctuates markedly over time, and that corresponding diagnoses can vary greatly within the same patient.

Our study also supports the argument of Kessler et al5 that mild cases of mental illness should be retained in the DSM-V, regardless of a treatment requirement, because they reflect a significant number of undiagnosed but distressed cases of depression. There may well be value in treatment of those cases. Primary care settings are commonly the first point of contact for depressed patients. Primary care physicians frequently provide the majority of, at least, the initial treatment for these patients. Although the evidence supporting the effectiveness of antidepressant medication for minor depression is not as strong as that for major depression, close monitoring and periodic reassessment of depressive symptoms is recommended for patients with minor depression. When symptoms of minor depression persist or worsen or when there is increasing functional impairment, antidepressant medication should be considered.24

With the reminder that it is incumbent upon physicians to do no harm, efforts in both primary and specialized care settings to screen for, assess, diagnose, and treat subjects with minor depression are consistent with good clinical practice. Furthermore, accepting minor depression as a diagnostic code in the DSM will be a very important step that would increase the accuracy and detection of cases, allow insurance coverage for those patients who might not otherwise receive treatment, and might possibly prevent or limit future morbidities and decrease the mortality of the illness. This is especially important in light of a recent, large prospective study that suggested minor depression is highly predictive of major depression later in time.11

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional and retrospective design. Course characteristics and treatment response were not available. Some of the data are based upon the self-reports of treatment-seeking patients. Moreover, even those patients who are categorized as having minor depression were individuals who presented to a psychiatric clinic for some reason.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that the diagnosis of minor depression seems to be a milder presentation on a continuum of severity of the same illness called major depression. Reaching a consensus on this point should help reduce stigma and assure therapeutic help for many people suffering from a mood disorder.

Potential conflicts of interest: None reported.

Funding support: None reported.

Previous presentation: These data were presented, in part, at the 158th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 21–26, 2005; Atlanta, Georgia.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robbins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile two surveys' estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(2):115–123. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regier DA, Narrow WE. Defining clinically significant psychopathology with epidemiologic data. In: Helzer JE, Hudziak JJ, editors. Defining Psychopathology in the 21st Century: DSM-V and Beyond. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002. pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Burglung P, et al. Mild disorders should not be eliminated from the DSM-V. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1117–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merikangas KR, Ernst C, Maier W, et al. Minor depression. In: Widiger T, Frances A, Pincus H, et al., editors. DSM-IV Sourcebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2005. pp. 97–108. Vol 2, Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Zhao S, Balzer DG, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and course on minor depression and major depression in the national comorbidity survey. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(1–2):19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pincus HA, Davis WW, McQueen LE. Subthreshold" mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:288–296. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Hays RD, et al. Subthreshold depression and depressive disorder: clinical characteristics of general medical and mental health specialty outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(12):1777–1784. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapaport MH, Judd LL, Schettler PJ, et al. A descriptive analysis of minor depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):637–643. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Broadhead WE, et al. Minor depression in family practice: functional morbidity, co-morbidity, service utilization and outcome. Psychol Med. 2000;30(6):1377–1390. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126(7):983–987. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guze SB. The need for toughmindedness in psychiatric thinking. South Med J. 1970;63(6):662–671. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guze SB. Why Psychiatry Is a Branch of Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Othmer E, Penick EC, Powell BJ. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview (PDI) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Othmer E, Penick EC, Powell BJ, et al. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derogatis LR. Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1975. Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90-R) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750190059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weller RA, Penick EC, Powell BJ, et al. Agreement between two structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews: DIS and the PDI. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(85)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell BJ, Penick EC, Othmer E. The discriminate validity of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(8):320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judd LL, Akiskal H, Zeller PJ, et al. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(4):375–380. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiskal HS, Judd LL, Gillin JC, et al. Subthreshold depression: clinical and polysomnographic validation of dysthymic, residual and masked forms. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(1-2):53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams JW, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care, a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000;284(12):1519–1526. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]