Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this review was to examine the risk of depression onset in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, discuss the importance and rationale for screening for major depressive disorder (MDD) in women in the menopausal transition, and review therapeutic options for management of MDD in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Data Sources:

PubMed was searched (1970 to 2008) using combinations of the following terms: major depressive disorder, perimenopause, postmenopause, mood disorder, risk factors, reproductive period, family practice, differential diagnosis, hormone, estrogen replacement therapy, reuptake inhibitors, and neurotransmitter.

Study Selection:

All relevant articles identified via the search terms reporting original data and published in English were considered for inclusion. Twenty-two cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were utilized to evaluate the relationship between the menopausal transition and risk of mood disorders and to formulate recommendations for screening and management of MDD in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Data Extraction:

Research studies utilized the following measures: postal questionnaires, Women's Health Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale, Modified Menopause Symptom Inventory, 12-item symptom questionnaire, or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Data Synthesis:

Menopause is a normal, and for most women largely uneventful, part of life. For some women, however, the menopausal transition is a period of biologic vulnerability with noticeable physiologic, psychological, and somatic symptoms. The perimenopausal period is associated with a higher vulnerability for depression, with risk rising from early to late perimenopause and decreasing during postmenopause. Women with a history of depression are up to 5 times more likely to have a MDD diagnosis during this time period.

Conclusions:

Routine screening of this at-risk population followed by careful assessment for depressive symptoms can help identify the presence of MDD in the menopausal transition. Recognition of menopausal symptoms, with or without depression, is important given their potential impact on quality of life.

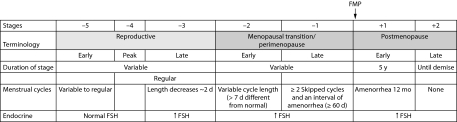

Reproductive aging is more of a progression than a series of discrete events.1 Events associated with reproductive aging (ie, perimenopause, postmenopause), though distinct when observed retrospectively, are indistinct when viewed prospectively. The duration of the stages of the menopausal transition is variable (Figure 1).1 The menopausal transition begins with changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which typically coincide with observable alterations in the menstrual cycle.2–4 However, hormonal fluctuations may occur without associated changes in the menstrual cycle; it is thus important to recognize that menopausal symptoms may precede noticeable menstrual cycle changes in midlife women. The median age at onset of the perimenopause in the United States is 47.5 years of age,5 the median age at menopause is approximately 51.3 years,5,6 and “early postmenopause” is defined as the 5 years post–final menstrual period (FMP).1

Figure 1.

Staging System for Menopausal Statusa

aReproduced with permission from Soules et al.1

Abbreviations: FMP=final menstrual period, FSH=follicle-stimulating hormone.

The menopausal transition is often marked by somatic symptoms (aches and pains, myalgia, fatigue), physiologic symptoms (vasomotor symptoms [VMS] of hot flashes and nighttime awakenings), other symptoms (sleep disturbances, sexual arousal disorders, and urogenital complaints), and psychological symptoms (irritability, anxiety, low libido).2,7,8 Overall, this period may represent a time of higher vulnerability for psychiatric problems and generally poorer quality of life.9,10

It is established that, from menarche to menopause, women experience monthly fluctuations of gonadal steroids such as estrogen and progesterone, which have some degree of neuromodulatory effects.11 During the perimenopausal period, these normally cyclic hormonal fluctuations become increasingly erratic followed by progressively longer periods of estrogen withdrawal.6,12,13 It has been postulated that changes in these hormonally mediated neuromodulatory effects may heighten the risk for mood disorders in women with sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations (eg, during the premenstrual period, puerperium, and perimenopause). Thus, it is important to be aware of the potential links between reproductive events and the risk for development of depressive disorders and to assess for the presence of depression in women as they progress through the various stages of reproductive aging.

Clinical Points

♦ Women in the menopausal transition are at increased risk of major depressive disorder (MDD).

♦ Routine screening for MDD and menopausal symptoms in this at-risk population is crucial for effective management.

♦ Potential interventions include estrogen therapy, antidepressant medications, or both.

In this review, we examine the risk of depressive onset in women during the menopausal transition and beyond, comparing and describing the clinical presentation of women experiencing depression who are premenopausal, perimenopausal, early postmenopausal, and late postmenopausal (> 5 years post-FMP). We also discuss the importance and rationale for screening for major depressive disorder (MDD) in women in the menopausal transition, identify key factors and assessments used to recognize MDD during this time, and review therapeutic options for the management of MDD in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

To achieve these objectives, a literature review was performed. was searched (1970 to 2008) using combinations of the following key search terms: major depressive disorder, perimenopause, postmenopause, mood disorder, risk factors, reproductive period, family practice, differential diagnosis, hormone, estrogen replacement therapy, reuptake inhibitors, and neurotransmitter. All relevant articles identified via the search terms reporting original data and published in English were considered for inclusion. Twenty-two cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of depression and menopause were utilized to evaluate the relationship between the menopausal transition and an increased risk of mood disorders and to formulate recommendations for the screening and management of MDD in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (see Table 1). Research studies were utilized with the following measures: postal questionnaires, Women's Health Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale, Modified Menopause Symptom Inventory, 12-item symptom questionnaire, or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Table 1.

Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies of Depression and Menopausea

| Authors, Year, Setting | Study Type | n at Baseline (%)b | Follow-Up, y | Measure | Results | Limitations |

| McKinlay and Jefferys, 1974, United Kingdom40 | Cross-sectional | Premenopausal: 134 (21) | ∼1 | Postal questionnaire | Depression most frequent symptom all groups; hot flashes and night sweats peak during perimenopause | 8 postmenopausal groupings requiring age at last menses, possible recall errors, self-report |

| Perimenopausal: 234 (37) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 270 (42) | ||||||

| Ballinger, 1975, United Kingdom21 | Cross-sectional | Premenopausal: 228 (45) | ∼1 | Postal questionnaire | Preponderance of “psychiatric cases” in perimenopausal group and women aged 45–49 y | Self-report, smallest number in perimenopausal group |

| Perimenopausal: 81 (16) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 193 (38) | ||||||

| Bungay et al, 1980, United Kingdom7 | Cross-sectional | 806 women stratified in 5-y age groups, aged 30–64 y | ∼ 1 | Postal questionnaire | Peaks of prevalence of psychiatric symptoms just before mean age of menopause | Self-report, no clear indication of association of chronological age and menopausal age |

| Hunter and Whitehead, 1989, United Kingdom46 | Cross-sectional | Premenopausal: 248 | Not clear | Postal questionnaire | Depressed mood was significantly increased in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women; distress greatest among younger postmenopausal women | Population sample was volunteer based |

| Perimenopausal: 351 | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 761 | ||||||

| Hunter, 1990, United Kingdom80 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 6 (13) | 3 | WHQ | Depressed mood significantly increased between premenopause and perimenopause or postmenopause | Small sample size |

| Perimenopausal: 31 (66) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 10 (21) | ||||||

| Matthews et al, 1990, United States62 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 541 | 2.5 | BDI | No significant changes in depressive symptoms from premenopause to postmenopause | Short follow-up |

| Kaufert et al, 1992, United States22 | Longitudinal | Total: 469 | 3 | CES-D | Natural menopause does not appear to increase odds of depression | Initial sample of women not random |

| Koster and Davidsen, 1993, Denmark47 | Retrospective, longitudinal | Premenopausal: 205 (39) | 4 | Postal questionnaire | Depression increased slightly during perimenopause | Study population recruited from metropolitan suburb areas in Denmark |

| Perimenopausal: 67 (13) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 51 (10) | ||||||

| Avis et al, 1994, United States23 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 485 (21) | 5 | CES-D | Onset of menopause not significantly associated with increased risk of depression; significant increased risk of depression associated with perimenopause vs postmenopause (in model that excluded menopausal symptoms) | Symptoms and depression measured by self-report |

| Perimenopausal: 1549 (66) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 240 (10) | ||||||

| Surgical: 78 (3) | ||||||

| Collins and Landgren, 1994, Sweden81 | Cross-sectional | Premenopausal: 967 (73) | Not clear | MMSI | Small but significant differences between premenopausal and postmenopausal women regarding negative mood | Self-report, few perimenopausal subjects included |

| Perimenopausal: 79 (6) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 278 (21) | ||||||

| Bromberger et al, 2001, United States24 | Cross-sectional,longitudinal | Premenopausal: 4483 (43) | 5 | 12-item symptom questionnaire | Highest rates of psychological distress in early perimenopause, lowest in premenopause and postmenopause; odds of distress varied by ethnic group | No hormonal data to validate menopausal status; checklist used was not a validated instrument |

| Perimenopause: | ||||||

| Early: 3534 (34) | ||||||

| Late: 609 (6) | ||||||

| Postmenopause: 1748 (17) | ||||||

| Avis et al, 2001, United States48 | Prospective, observational | Premenopausal: 129 | Not clear | CES-D | CES-D score not significantly associated with premenopause, perimenopause, or postmenopause | Symptoms of depression measured by self- report |

| Perimenopausal: 99 | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 64 | ||||||

| Maartens et al, 2002, Netherlands49 | Cross-sectional, longitudinal | Premenopausal: 475 (23) | 2.8–4.7 | EDS | Transition from perimenopause to postmenopause significantly associated with increased EDS score | Measured depressive symptoms rather than assessing diagnosis of depression |

| Perimenopausal: 982 (47) | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 646 (31) | ||||||

| Bromberger et al, 2003, United States30 | Community- based, cross- sectional, longitudinal | Premenopausal: 1688 (53) | Not clear | Symptom questionnaire | Early perimenopause associated with increased odds of dysphoric mood, irritability, and nervousness compared with premenopause | Overall measure of dysphoric mood was not validated; no prospective menstrual diary data |

| Perimenopausal: 1473 (47) | ||||||

| Freeman et al, 2004, United States25 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 436 | 4 | CES-D | Increased risk of depression during transition to menopause, which decreased during postmenopause; risk of depression decreased with rapidly increasing FSH levels | Less than 5% of patients reached menopausal status during the 4-year study; only measured hormone levels during follicular phase; patient sample limited to African American and white women |

| Schmidt et al, 2004, United States39 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 29 | 5 | SCID | Events related to the late and early perimenopause as well as early postmenopause may be associated with an increased susceptibility to develop depression in some women | Small sample size; inability to prospectively confirm incidence of depression during other periods of life |

| Travers et al, 2005, Australia41 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 88 | Not clear | GCS | Premenopausal and perimenopausal women had higher depression scores vs postmenopausal women; women in earlypostmenopause had higher depression scores vs women in intermediate or late postmenopause | In this normative study, population evaluated was derived from a geographical sector of a large Australian city, leaving some racial and ethnic groups underrepresented |

| Perimenopausal: 34 | ||||||

| Postmenopausal: 314 | ||||||

| Cohen et al, 2006, United States28 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 460 | 3, then 6 | CES-D | In women with no history of depression, those who enter the menopausal transition earlier have significant risk for first-onset depression | Prospective assessment of depression not based on structured clinical interviews; at end of initial 3-y period, follow-up interval was 59–92 mo; result is imprecise temporal relationship between menopausal transition and new onset of depression |

| Freeman et al, 2006, United States29 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 231 | 8 | CES-D | Transition to menopause strongly associated with new onset of depressed mood among women with no history of depression, especially with greater hormonal flux | Fixed intervals of follow-up assessments may lack precision |

| Bromberger et al, 2007, United States26 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 3,302 | 5 | CES-D | Change in menopausal status associated with increased risk of significant depressive symptoms, independent of relevant demographic, psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors | Measured current depressive symptoms rather than diagnosis of clinical depression |

| Freeman et al, 2007, United States50 | Longitudinal | Premenopausal: 367 | 9 | Symptom questionnaire | Depressed mood higher through late premenopause and early and late perimenopause; decreased postmenopause | Findings based on participants' self-reporting of symptom occurrence and severity rather than diagnosis of symptoms |

| Perimenopausal: 37 | ||||||

| Woods et al, 2008, United States 82 | Longitudinal | Total: 302 | 15 | CES-D | Age, late menopause, and hot flashes were significantly associated with depressed mood | Symptoms of depression measured by self-report |

Data from Burt et al.79

Percentages were not provided for all groups.

Abbreviations: BDI=Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale, EDS=Edinburgh Depression Scale, FSH=follicle-stimulating hormone, GCS=Greene Climacteric Scale, MMSI=Modified Menopause Symptom Inventory, SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, WHQ=Women's Health Questionnaire.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DEPRESSION IN PERIMENOPAUSAL AND POSTMENOPAUSAL WOMEN

MDD is a chronic and frequently disabling disorder. The risk for MDD is approximately 1.5 to 3 times higher in women than in men,14 with an estimated lifetime prevalence in women of 21.3%.15 Notably, the difference in prevalence emerges around the time of puberty,16 suggesting a hormonal influence on the risk for depression.

Theories of Menopausal Mood Changes

Several theories have been employed to explain perimenopausal mood changes. The neurobiologic theory, also known as the estrogen withdrawal theory, posits that the hypoestrogenic state drives the onset or worsening of pre-existing mood symptoms in perimenopausal women at risk of depression. Mood symptoms occur secondary to changes in reproductive hormones.17 Theory supporters point out that estrogen affects brain levels and metabolism of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, β-endorphin, and serotonin, all of which can affect emotional pathways.18

In the domino theory, the hypoestrogenic state is again implicated, but indirectly; decreased estrogen levels are believed to be responsible for somatic symptoms (ie, hot flashes and night sweats) that lead to sleep disturbances, which cause daytime mood changes.18,19 In contrast, the psychosocial theory focuses on factors outside of biologic changes; mood symptoms are viewed as a response to altered roles and relationships associated with age-related life changes (eg, health problems or caring for aging parents).17,18 A combination of etiologies is likely in most women. It is reasonable to consider that changes in the presence of reproductive hormones could affect neurotransmitter activity in the central nervous system. Similarly, although the relationship between mood-related symptoms and somatic symptoms remains unclear, it is likely a bidirectional relationship, thus underscoring the importance of recognizing when 1 or both are present. Finally, causality between psychosocial factors and MDD is difficult to demonstrate conclusively, particularly when studied retrospectively; however, it is prudent to question patients about the presence and impact of such life stressors.

Risk of Depression During the Perimenopausal Period

A number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Table 1) have evaluated the relationship between the menopausal transition and an increased risk of mood disorder.20 Unsurprisingly, such a link has been documented for decades. In the 1970s, in a population sample of 539 women, there was a high prevalence of minor psychiatric illness in women 40 to 55 years old and evidence of an increase in psychiatric morbidity before menopause lasting approximately 1 year after FMP.21 Some studies, however, suggested that the increase in symptoms is more closely related to other factors, such as physical health or psychosocial stressors, rather than the transition to menopause.22,23 In 1994, Avis and colleagues23 reported that a long perimenopausal period was associated with a slight increase in risk for depression but that this was explained by increased somatic menopausal symptom reporting. Although the authors concluded that the onset of the menopausal transition alone was not associated with an elevated risk of depression, more recent evidence suggests otherwise.23

Further studies suggest that perimenopause does represent a time of higher vulnerability for psychiatric problems.24,25 In a national, multiethnic study of menopause and aging (10,374 women aged 40 to 55 years), early perimenopausal women had higher odds of reporting distress compared with postmenopausal women.24 Researchers found that psychological distress during the transition to menopause is transient for most women but not all.24

Freeman and colleagues25 conducted a longitudinal, population-based cohort study and concluded that depressive symptoms increased during the transition to menopause and decreased following menopause after controlling for variables such as previous depression, age, sleep patterns, VMS, ethnicity, and work status. Another study by Kumari et al10 found that the association between perimenopausal depression and functional decline was statisically significant on all health functioning scales for women in the menopausal transition, suggesting a noticeable decrease in health functioning for a subset of women. A socially or health-compromised position contributed to a more symptomatic transition.10

Most recently, an analysis of data from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation research also found a correlation between the menopausal transition and an increased risk of clinically relevant depressive symptoms.26 Bromberger and colleagues26 examined the association between change in menopausal status and the risk of depressive symptoms in a multiethnic, longitudinal, prospective cohort study that followed 3,302 women aged 42 to 52 years over 5 years. The authors found that the risk for depressive symptoms increased with the beginning of the menopausal transition and stayed elevated through early postmenopause and was independent of relevant demographic, psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors.26

The risk for recurrence of MDD during the perimenopausal period in women with a history of depression has been well documented.27 However, many studies reporting a link between menopausal status and depressive symptoms did not specifically exclude women with a history of depression, leading to some controversy. Two recent studies have independently demonstrated that the perimenopausal period was indeed associated with an increased risk for the development of depressive symptoms, even among women with no previous history of depression.28,29 Cohen and colleagues28 conducted a longitudinal, prospective cohort study in 460 women aged 36 to 45 years (premenopausal at enrollment) without a history of MDD. Compared with women who remained premenopausal, perimenopausal women were twice as likely to develop clear symptoms of depression,28 indicating a significant increase in risk.

Similarly, Freeman and colleagues29 examined 8 years of longitudinal data from a cohort of 231 women from their previous study25 who had no history of depression. They found that women were 4 times as likely to develop depressive symptoms and were 2.5 times more likely to have a diagnosis of MDD during the transition to menopause than when they were premenopausal.29 Moreover, they observed that the greater the degree of hormonal flux, the greater the risk for MDD, thus strengthening the proposed biologic link between the hormonal fluctuations and depressive vulnerability.29

In summary, numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown some evidence of increased risk of depressive symptoms during the perimenopausal period. More recently, 2 longitudinal, cohort studies that prospectively tracked initially premenopausal women for 5 to 8 years as they transitioned through menopause28,29 documented an increase in risk for the development of depressive symptoms among women with no history of depression.

Risk Factors for Depressive Onset

Although it has been demonstrated that the menopausal transition is an independent risk factor for the development of MDD,28,29 numerous other factors can modify this risk. These risk factors can be grouped into several somewhat overlapping categories (Table 2): demographic (eg, ethnicity, educational level), psychiatric (eg, history of depressed mood or depression, comorbidity), psychosocial (eg, stressful life events, unhealthy lifestyle, marital concerns, negative attitudes regarding aging/menopause), and menopausal (eg, VMS and other physical symptoms, premenstrual syndrome [PMS], early natural menopause, menopausal transition ≥ 27 months, abrupt/surgical menopause). This section will examine a number of these factors with an emphasis on those that appear to impart the greatest influence on the risk for depression.

Table 2.

Risk Factors for the Onset of Depression During the Menopausal Transition

| Category | Risk Factor |

| Demographic | White ethnicity30 |

| Lower educational level30 | |

| Psychiatric | History of depressed mood/depression25 |

| Comorbidity10 | |

| Psychosocial | Stressful life events22 |

| Unhealthy lifestyle83 | |

| Marital concerns31,32 | |

| Negative attitudes toward aging/menopause33 | |

| Menopausal | Vasomotor symptoms and other physical symptoms23,34,35 |

| Premenstrual syndrome37 | |

| Early natural menopause42 | |

| Stage of menopausal transition25,39,82 | |

| Greater hormonal fluctuations changes during menopausal transition25 | |

| Longer menopausal transition (≥ 27 mo)23 | |

| Abrupt/surgical menopause22 |

The menopausal transition is not uniformly perceived; one individual's stressful life event (eg, empty nest) may be viewed by another as liberation from decades-long duties. In a multiethnic community study in the United States, Bromberger and investigators24 found a significant association between distress and the transition to menopause, with greater odds of psychological distress during the transition to menopause among white women than among women of other ethnicities (African-American, Hispanic, Chinese, Japanese).24 The authors further reasoned that overall, the perimenopause was associated with a heightened risk for psychological distress that also could be influenced by psychosocial aspects of women's lives potentially related to their ethnicity.24 A follow-up report to this study investigated the relationship between persistent mood symptoms and menopause and found that middle-aged women of African-American and Asian descent had lower risks than white women for several of the individual mood symptoms examined.30

A history of depression has been shown to heighten the risk of MDD during perimenopause. In the Penn Ovarian Aging Study, a cohort of 436 premenopausal women was followed for 4 years.25 Women with a history of depression were more than twice as likely to report depressive symptoms and nearly 5 times as likely to have an MDD diagnosis in the menopausal transition compared with women with no history of depression.25

Stressful life events, perceptions of poor health, and surgical menopause have similarly been associated with an elevated risk of depressive onset in perimenopausal women.22 Other factors linked to depressive onset include marital concerns,31,32 poor health or medical illness,10 smoking,10 lower levels of educational attainment,30 and negative attitudes toward aging and menopause.33

Menopausal symptoms themselves are also predictors of depression or MDD. For example, in the Penn Ovarian Aging Study, hot flashes and poor sleep independently predicted MDD.25 Other studies have found that women who reported vasomotor and other physical symptoms had elevated rates of depression23,28 and a higher intensity of anxiety and depression.34 In another study, the presence of VMS in perimenopausal women increased the risk of depression 4-fold compared with the group of women without hot flashes.35

Reproductive Events and Depression

Some evidence suggests that women who experience depression associated with one reproductive event may be at risk for recurrence at a later event.36 For example, in a population-based cohort study of early perimenopausal women (aged 35 to 47 years at enrollment), Freeman and colleagues37 observed that women with PMS at enrollment were more likely to experience depressed mood than women without PMS.

It is possible that some women may be more vulnerable to depression during times of gonadal hormone flux throughout the reproductive life cycle (eg, late luteal phase, pregnancy, postpartum, and perimenopause).38 In addition, evidence suggests that gonadal hormone fluctuations, increased with ovarian aging, may be an important factor for the onset and continuation of depressive symptoms.28,29

Finally, the risk of depression varies during different stages of the menopausal transition28,39 and is heightened by the presence of VMS.28 The risk of depressive onset starts increasing in early perimenopause, is greatest in late perimenopause,39 and decreases after menopause,25 with some evidence suggesting the risk is higher in early postmenopause (≤ 5 years post-FMP) and decreases 5 to 10 years after menopause.23,40,41 A lengthy or early menopausal transition may increase the risk for depression.23,42 Conversely, women with a history of MDD experience earlier transition to menopause or ovarian failure.43

Thus, multiple physical, psychological, and psychosocial factors may predispose women to depression during otherwise normal fluctuations in hormone levels that occur throughout the reproductive life cycle.38 In general, external stressors have a greater impact on depression onset during the early reproductive years, whereas the underlying biology appears to be more important during the menopausal transition.25 The combination of physiologic, psychological, and somatic changes during this transition can lead to frequent visits to primary care physicians, requiring clinician awareness.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND CHALLENGES IN RECOGNITION OF DEPRESSION IN PRIMARY CARE

Specific Aspects of Depression During the Menopausal Transition

The depression experienced by women throughout the menopausal transition and beyond may be different from that of premenopausal women; both the time course of symptom presentation and the nature of symptoms may vary. For example, in premenopausal women, depressive symptoms are often associated with or exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle,44 suggesting an association with hormonal changes. In perimenopausal women, however, hormonal changes are not necessarily limited to the luteal phase, and, therefore, symptoms may not follow a predictable cyclical pattern. In elderly women, depression may be primarily associated with symptoms of impaired cognitive function that is followed by cognitive decline.45

Depressive symptoms may also differ substantially during the various stages of menopausal transition,30,40,41,46–50 and the age at which a woman experiences the menopausal transition may also affect the degree of distress related to symptoms.46 In the early 1970s, McKinlay and Jefferys40 reported an increase in symptoms of sleeplessness, depression, weight increase, and palpitations in women transitioning from premenopause to menopause. In addition, the latter 2 symptoms were decreased in women in late postmenopause (ie, ≥ 9 years post-FMP).

Additional studies have demonstrated increased depressed mood and irritability during the transition from premenopause to perimenopause30,46,47,49 and the subsequent decrease of depressive symptoms during postmenopause in some samples47,50 but not others.46,49 A longitudinal cohort study of 500 premenopausal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal women conducted in Australia reported that women in early postmenopause (2–3 years post-FMP) experienced greater vasomotor, depressive, and sexual dysfunction symptoms compared with women in intermediate (4–9 years post-FMP) or late (≥ 10 years post-FMP) postmenopause (P ≤ .03 for each comparison).41

Presenting symptoms of MDD in primary care patients are often relatively nonspecific somatic symptoms making recognition and diagnosis of MDD challenging.51 This is particularly relevant in the case of midlife women, in that physical symptoms associated with the menopausal transition may be the primary presenting complaint or may overshadow emotional or cognitive complaints.

Even if the constellation of symptoms of depression experienced by women throughout the menopausal transition (and beyond) is different from that of premenopausal women, there is no specific diagnosis of perimenopausal MDD per se. MDD that occurs during the perimenopausal period should be viewed and diagnosed using the same criteria as in any other patient.

Importance and Rationale for Screening

Despite the high prevalence of depression, studies have shown that family physicians may fail to recognize up to 30%–50% of patients with MDD,52–54 particularly when patients present with somatic symptoms,51 perhaps due to time constraints. Primary care physicians need reliable methods for identifying patients with depression so that they can assess patients quickly and efficiently and improve identification and patient outcomes.54 Thus, it is important to identify factors that can serve as “flags” for a potential increased risk for MDD. Women who are at or approaching menopausal age, particularly those with changes in menstrual patterns and/or menopausal symptoms, may represent such a group. In addition, clinicians also should inquire about a history of any depression or reproductive cycle–related mood disturbance, which may help predict vulnerabilities during this time period. It is also important to ascertain the presence and severity of menopausal symptoms, given the documented increase in risk among women experiencing VMS. Such symptoms are often the primary reason for seeking treatment among midlife women, offering primary care physicians an opportunity to screen for the presence of psychiatric conditions.

In summary, it is possible that the symptoms of depression experienced by perimenopausal and postmenopausal women differ somewhat from those of premenopausal women. Nevertheless, it may be difficult to recognize depression in midlife women because of the nonspecific nature of many symptoms and the lack of specific criteria for diagnosis based on menopausal status.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Key Factors

It is well known that the menopausal transition is marked by changes in the female hormonal profile, with perimenopausal women reporting a variety of somatic, physiologic, and psychological symptoms. The outcomes of numerous cross-sectional and prospective community-based studies indicate that perimenopausal women are more likely to report depressive symptoms than premenopausal women.20 Life stressors such as marital issues, changes in caretaking (eg, children departing the home, aging parents) or career responsibilities, issues related to aging, and feelings of being “overextended” also have been linked to perimenopausal depression.18 Symptoms often cited as common to both depression and the transition to menopause include low energy, poor concentration, sleep problems, weight changes, and decreased libido.8,18,55 Routinely inquiring about these factors may help clinicians identify perimenopausal women with depression.

Assessments

In a primary care setting, it is useful to assess the number and severity of symptoms at presentation. There may be subtle qualitative differences in certain symptoms common to both depression and the transition to menopause, which may aid in recognition of other related symptoms or potentially affect treatment strategies (eg, sleep disruption secondary to night sweats might be approached differently than anxiety or mood-driven sleep problems). However, to achieve an accurate diagnosis, it is imperative that initial screening for the presence of MDD in perimenopausal women focus on the overall number and type of symptoms, their duration, and associated impairment according to DSM-IV criteria.55 If a woman experiences 5 or more symptoms on most days for 2 or more weeks with resultant impairment of functioning, the diagnosis of MDD can be made.55 Moreover, a diagnosis of MDD should be made if the criteria are met regardless of whether 1 or more of these symptoms might overlap with what might be considered “menopausal” symptoms.

Table 3 lists essential elements for assessment in midlife women (aged 40 to 55 years) who present with depressive or anxious symptoms. These assessments help ascertain the presence of depression in women with potentially confounding symptoms and to identify risk factors for individual women.

Table 3.

Essential Elements for Assessment in Midlife Womena

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) | |||

| Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? | 0=not at all | ||

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 1=several days | ||

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 2=more than half the days | ||

| 3=nearly every day | |||

| Total Score Items 1 & 2 | Probability of MDD (%) | Probability of Any Depressive Disorder (%) | |

| 1 | 15.4 | 36.9 | |

| 2 | 21.1 | 48.3 | |

| 3 | 38.4 | 75.0 | |

| 4 | 45.5 | 81.2 | |

| 5 | 56.4 | 84.6 | |

| 6 | 78.6 | 92.9 | |

| Symptoms of Depression (DSM-IV)b | Yes | No | |

| Are you experiencing sleep problems (sleeping too much or too little)?† | |||

| Do you have a lack of interest (a deficit) in doing things you previously enjoyed? | |||

| Are you experiencing feelings of guilt, worthlessness,† hopelessness,† or regret? | |||

| Do you have an energy deficit† or are you suffering from fatigue? | |||

| Do you have difficulty concentrating?† | |||

| Has your appetite either increased or decreased† recently? | |||

| Do you have difficulty concentrating? | |||

| Do you have recurrent thoughts of death or suicide? | |||

| Reproductive History | Yes | No | |

| Are you menstruating regularly? | |||

| Have you had a period in the last year? | |||

| Are you taking birth control pills? | |||

| Are you on hormone replacement therapy? | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with postpartum depression? | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with premenstrual dysphoric disorder? | |||

To meet a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a patient must have 4 of the symptoms plus depressed mood or anhedonia for at least 2 weeks. To meet a diagnosis of dysthymic disorder, the patient must have 2 of 6 symptoms marked with † plus depressed mood for at least 2 years.

The patient's reproductive and psychiatric history are also important factors that may influence the risk of depression or confound diagnosis and treatment.56 This should include an assessment of the patient's reproductive status, including past or current use of hormone-replacement therapy, a history of prior hormone- or reproductive event–related mood disturbances, and prior or current psychiatric diagnoses.56

Assessment Tools

In primary care, the initial assessment of depression should be practice based (ie, questionnaires administered to all patients) and case finding (ie, questionnaires administered to established patients considered at high risk).54 Although these approaches can be time consuming and, depending on the tools used, may yield a large number of “false positives,”54 the menopausal transition may be a time during which the increased risk for depression warrants both initial and repeat screening of patients.

Assessment tools that are accurate and quick to administer are necessary.54 Serial questionnaires (eg, a short, easy-to-score test with high sensitivity followed by a longer test with high specificity) may be more efficient and accurate than a single longer questionnaire such as the Beck Depression Inventory or Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D).54,57

In particular, the use of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2 followed by the PHQ-9 may prove appropriate54 and is relatively easy to incorporate into daily practice. The PHQ-2 assesses for the presence and degree of anhedonia and dysphoria, which are criteria for MDD.54,55 The PHQ-9 serves to confirm the diagnosis.54,58,59 Serial screening with the PHQ-2 followed by the PHQ-9 yields accurate results (95.1%) and a low enough pass-through rate of screened patients (19.3%) so that the process does not get bogged down.54

Perhaps an even more practical option is the use of a brief verbal inquiry as an alternative to the written form of the PHQ-2. A cross-sectional study found that 2 questions (“During the past month have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?”), which correspond to the items in the PHQ-2, had a sensitivity and a specificity60 similar to that of the written PHQ-2.54 The questions detected most cases of depression in a community setting with a reasonable tradeoff in false positives.60

Confirmation of a diagnosis of major depressive episode using the PHQ-2 and the PHQ-9 should be followed by verification that there are no physical or medical causes of symptoms, no other symptoms that may mimic depression, and no manic episodes that could confound the diagnosis.54 Table 4 is a summary of selected assessment tools to consider for both MDD and menopause in primary care settings, including the PHQ and patient self-rating questionnaires such as the CES-D.61 Despite their use in studies of women in the menopausal transition,22,23,28,29,62 some of the older instruments may be difficult to use or require too much time to administer54 to be practical for screening in routine primary care practice. These instruments might be better suited for ongoing symptom monitoring in patients who have been diagnosed with MDD.54

Table 4.

Summary of Selected Questionnaires for the Detection of Major Depressive Episode in Primary Care Settingsa

| Instrument | Date of Introduction, Time Frame for Questions | Self-Report or Clinician Administered | Items | Administration Time (min) |

| PHQ-2 | 2003, last 2 wk | Clinician administered | 2 | < 1 |

| PHQ-9b | 1999, last 2 wk | Clinician administered | 9 | < 3 |

| MOS-D | 1995, last wk | Self-report | 8 | < 2 |

| BDIb | 1961, last 2 wk | Self-report | 21 | 2–5 |

| CES-Db | 1977, last wk | Self-report | 20 | 2–5 |

| GHQ | 1972, last few wk | Self-report | 28 | 5–10 |

| Zung Depressionb | 1983, recently | Self-report | 20 | 2–5 |

Based on Mulrow et al.84

Validated for repeated administration to monitor change/treatment response.

Abbreviations: BDI=Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale, GHQ=General Health Questionnaire, MOS-D=Medical Outcomes Study-Depression scale, PHQ=Patient Health Questionnaire.

In diagnosing depression during the menopausal transition, a family physician should consider that there may be unique symptoms associated with depression or perimenopause. In addition, even symptoms that could reasonably be attributed to the menopausal transition (such as low energy, reduced concentration, problems with sleep and weight, and decreased sexual drive) should be considered potential symptoms of depression. Assessment tools that are quick and easy, with high sensitivity and specificity, and in written or verbal form exist and may prove beneficial.

MANAGEMENT

Hormone Level Measurement

Hormonal levels (eg, follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH] and serum estradiol) can serve as indicators of menopausal status. Typically, elevated FSH levels (> 10 IU/L on cycle days 2–4) occur early in the perimenopause and may be the first sign of reproductive aging1; later, estradiol levels begin to decrease (< 80 pmol/L).2 FSH levels are rarely elevated in women with regular menstrual cycles and typically do not change once they are elevated.1 Assessment of hormone levels may be reassuring to the patient, although this information alone is generally not sufficient to precisely determine the specific stage of the perimenopause. For example, circulating FSH levels can vary substantially among women, irrespective of menopausal status and across menstrual cycles within the same patient.63,64 Moreover, decreases in estradiol may be difficult to detect during the transition to menopause, as much of the reduction in estradiol occurs during the postmenopausal period. However, along with clinical presentation and psychiatric history, the measurement of hormone levels can be used to help assess the appropriateness of potential interventions such as psychiatric treatment, psychotherapy, or hormonal therapy.

Estrogen Replacement Therapy and Psychiatric Treatments

Estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) may be appropriate for improving the menopausal symptoms in some perimenopausal women with depression. Although the role of gonadal hormones as neuromodulators has been established, their efficacy in improving the symptoms of depression during the menopausal transition remains unclear. Results of separate randomized controlled trials showed that 6 to 12 weeks of treatment with transdermal estradiol 50 to 100 μg/d in perimenopausal women effectively improved remission rates from depressive symptoms compared with placebo (68%–80% versus 20%–23%, respectively).65,66 However, another randomized controlled study demonstrated that transdermal estradiol 100 μg/d for 8 weeks was not efficacious in improving symptoms of depression in postmenopausal women.67 Additional large-scale controlled studies are needed to clearly define the efficacy of hormonal treatment strategies for depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Some studies have suggested that ERT may improve the response to antidepressant treatment. In 1 study of depressed women over age 60 years, response to fluoxetine appeared to be greater among women who were also taking ERT.68 In another study with a similar population, ERT augmented the response to sertraline in terms of quality of life and general improvement.69 However, other studies have not found such an effect. For example, a study by Amsterdam and colleagues70 showed no difference between women aged 45 years and over taking fluoxetine plus ERT (n=40) compared with patients taking fluoxetine alone (n=790).

ERT is associated with other risks, such as breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Thus, it is not likely to be an appropriate therapy for older postmenopausal women or younger women with a familial risk for breast cancer or cardiovascular disease.20 Moreover, the 2002 Women's Health Initiative study of estrogen plus progestin therapy in postmenopausal women71 changed attitudes toward hormone replacement therapy, making women in general more reluctant to utilize this intervention.72 ERT may be appropriate for women in perimenopause who do not take hormonal contraceptives and are willing to take hormones to improve their menopausal symptoms. The role of hormone replacement therapy in the treatment of mood disorders remains unconfirmed.

As is true for MDD in other patient populations, antidepressants may be considered appropriate first-line therapy for moderate-to-severe depression in perimenopausal women. Antidepressants are generally effective in women across the lifespan, and few studies have prospectively assessed whether menopausal status influences antidepressant efficacy. However, there is some evidence of variability in the efficacy of some antidepressants (in particular, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) when used to treat depression in the context of perimenopausal hormonal changes.

Kornstein and colleagues73 reported that younger and older women had differential responsiveness to treatment with an SSRI versus a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA). In general, the data suggest that the effects of SSRIs in younger women are more robust compared with TCAs, but no differences were seen in older women.73 A 2006 study74 evaluated the effect of gender and menopausal status in antidepressant treatment response to various SSRIs in a primary care setting. Gender comparisons, which were adjusted for age, education, employment status, diagnosis, SSRI administered, baseline score, and treatment compliance, did not reveal significant differences. In contrast, menopausal status was a factor; menopausal women were less responsive to treatment with SSRIs compared with premenopausal women, a finding that was independent of age, education, SSRI taken, time, baseline PHQ-9 score, and treatment compliance (Table 5), suggesting that menopausal status could affect the response to SSRI treatment of MDD.74

Table 5.

Differences in Antidepressant Treatment Response as Measured With the PHQ-9a

| Comparison | Odds Ratio of Response (95% CI) |

| Women vs men | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) |

| Premenopausal vs postmenopausal | 2.1* (1.1 to 4.2) |

Based on Pinto-Meza et al.74

P < .05.

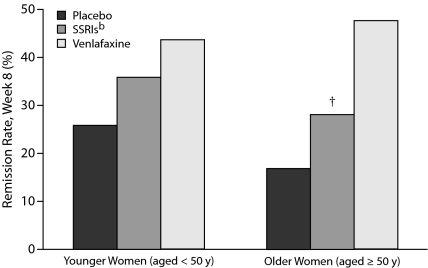

Menopausal or hormonal status does not seem to have the same degree of influence on the treatment response to other classes of antidepressants, such as the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).75,76 In a meta-analysis of 31 placebo-controlled trials of the SNRI venlafaxine and various SSRIs, age was used as a proxy for menopausal status.76 Although remission rates with SSRIs were significantly greater than with placebo in the group of younger women (aged 40 years and younger), there was not a significant difference among older women (over 55 years old).76 In contrast, remission rates with venlafaxine were significantly greater than with placebo among both younger and older women.76 An analysis of 8 placebo-controlled trials of venlafaxine and various SSRIs showed similar differences between younger and older women treated with SSRIs but not for those treated with venlafaxine (Figure 2).75 An analysis of the effects of hormone therapy on response75 showed that SSRI efficacy in older women was better if they were taking hormone therapy.

Figure 2.

Remission Rates With SNRIs/SSRIs for Younger Versus Older Womena,b

aAdapted with permission from Thase et al.75

bSSRIs include fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine.

†P < .05 vs. younger women.

Abbreviations: SNRI=selective-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

An analysis of pooled data from 2 studies evaluated the efficacy of acute treatment of MDD with the SNRI duloxetine in cohorts of women aged < 40 years, 40 to 55 years, and > 55 years.77 The degree of symptom improvement with duloxetine was comparable for all 3 groups, suggesting no differences in efficacy related to age or menopausal status.77 Comorbid conditions may make treatment of depression more difficult78 and may include migraine, fibromyalgia, menopausal somatic symptoms, and other medical comorbidities.

In summary, although estrogen therapy helps relieve menopausal symptoms in women, its role in the treatment of MDD has not been confirmed by large prospective studies. Generally, estrogen has not been consistently efficacious as monotherapy in the treatment of MDD, although women in the menopausal transition may be more responsive than postmenopausal women. The use of antidepressants to treat MDD is appropriate for women regardless of menopausal status; the efficacy of some antidepressants may vary depending on the presenceor absence of estrogen. Treatment selection for MDD in midlife women should take into account not only menopausal status, but also any comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions, as well as patient preferences.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence supports a link between female gonadal steroids and MDD. Women are at increased risk for MDD compared with men. In addition, depressive symptoms and MDD are evident during periods of hormonal flux (eg, premenstrual period).

Most women transition to menopause without mood disturbance, but the perimenopause may represent a period of higher vulnerability for depression with risk increasing from early to late perimenopause and decreasing during postmenopause. An early or lengthy perimenopause has been associated with a higher rate of depression. There is a bidirectional relationship between MDD and VMS. Additional risk factors include adverse life events or a history of depression. Women with a history of MDD may experience an earlier menopausal transition.

The recognition of MDD during the menopausal transition can be challenging given the constellation of symptoms and the overlap between depression and the transition to menopause. Assessment strategies may assist the physician in detecting depression and determining appropriate treatment strategies in perimenopausal women.

Drug names: duloxetine (Cymbalta), fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem, and others), fluvoxamine (Luvox and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), venlafaxine (Effexor and others).

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Clayton has received grant/research support from BioSante, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis; has served on the advisory boards of and as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, PGxHealth, and Sanofi-Aventis; has served on the speaker's bureau of and received honoraria from Eli Lilly; and has received royalties from Ballantine Books/Random House, Guilford Publications, and Healthcare Technology Systems, Inc. Dr Ninan is an employee of Pfizer Inc, formerly Wyeth Research.

Funding/support: This study was supported by Pfizer Inc, formerly Wyeth Research, Collegeville, Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Climacteric. 2001;4(4):267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. WHO Technical Report Series. Research on the Menopause in the 1990s. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall JE. Neuroendocrine changes with reproductive aging in women. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(5):344–351. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vadakkadath Meethal S, Atwood CS. The role of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal hormones in the normal structure and functioning of the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(3):257–270. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4381-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner JG. The normal menopause transition. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):103–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(92)90003-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison JH, Brinton RD, Schmidt PJ, et al. Estrogen, menopause, and the aging brain: how basic neuroscience can inform hormone therapy in women. J Neurosci. 2006;26(41):10332–10348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3369-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bungay GT, Vessey MP, McPherson CK. Study of symptoms in middle life with special reference to the menopause. BMJ. 1980;281(6234):181–183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6234.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holte A, Mikkelsen A. The menopausal syndrome: a factor analytic replication. Maturitas. 1991;13(3):193–203. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(91)90194-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utian WH. Psychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:47–56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumari M, Stafford M, Marmot M. The menopausal transition was associated in a prospective study with decreased health functioning in women who report menopausal symptoms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(7):719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yonkers KA. Special issues related to the treatment of depression in women. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 18):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santoro N. The menopausal transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall JE, Gill S. Neuroendocrine aspects of aging in women. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001;30(3):631–646. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle K.A, et al. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Menopause-related affective disorders: a justification for further study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(7):844–852. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.7.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasgon N, Shelton S, Halbreich U. Perimenopausal mental disorders: epidemiology and phenomenology. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(6):471–478. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff I, Regestein Q, Tulchinsky D, et al. Effects of estrogens on sleep and psychological state of hypogonadal women. JAMA. 1979;242(22):2405–2414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares CN, Cohen LS. Perimenopause and mood disturbance: an update. CNS Spectr. 2001;6:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballinger CB. Psychiatric morbidity and the menopause: screening of general population sample. BMJ. 1975;3(5979):344–346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5979.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufert PA, Gilbert P, Tate R. The Manitoba Project: a re-examination of the link between menopause and depression. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):143–155. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(92)90006-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avis NE, Brambilla D, McKinlay SM, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the association between menopause and depression: results from the Massachusetts Women's Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4(3):214–220. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bromberger JT, Meyer PM, Kravitz HM, et al. Psychologic distress and natural menopause: a multiethnic community study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1435–1442. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman E.W, Sammel MD, Liu L, et al. Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):62–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, et al. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Affect Disord. 2007;103(1-3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hay AG, Bancroft J, Johnstone EC. Affective symptoms in women attending a menopause clinic. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(4):513–516. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, et al. Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bromberger JT, Assmann SF, Avis NE, et al. Persistent mood symptoms in a multiethnic community cohort of pre- and perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(4):347–356. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reimherr F.W, Strong RE, Marchant BK, et al. Factors affecting return of symptoms 1 year after treatment in a 62-week controlled study of fluoxetine in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 22):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harlow BL, Cohen LS, Otto MW, et al. Early life menstrual characteristics and pregnancy experiences among women with and without major depression: The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1-3):167–176. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avis NE, McKinlay S.M. A longitudinal analysis of women's attitudes toward the menopause: results from the Massachusetts Women's Health Study. Maturitas. 1991;13(1):65–79. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(91)90286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumel JE, Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, et al. Relationship between psychological complaints and vasomotor symptoms during climacteric. Maturitas. 2004;49(3):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joffe H, Hall JE, Soares C.N, et al. Vasomotor symptoms are associated with depression in perimenopausal women seeking primary care. Menopause. 2002;9(6):392–398. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart DE, Boydell KM. Psychologic distress during menopause: associations across the reproductive life cycle. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1993;23(2):157–162. doi: 10.2190/026V-69M0-C0FF-7V7Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PJ, et al. Premenstrual syndrome as a predictor of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5, pt 1):960–966. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000124804.81095.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feld J, Halbreich U, Karkun S. The association of perimenopausal mood disorders with other reproductive-related disorders. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(6):461–470. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt PJ, Haq N, Rubinow DR. A longitudinal evaluation of the relationship between reproductive status and mood in perimenopausal women. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2238–2244. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKinlay SM, Jefferys M. The menopausal syndrome. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28(2):108–115. doi: 10.1136/jech.28.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Travers C, O'Neill SM, King R, et al. Greene Climacteric Scale: norms in an Australian population in relation to age and menopausal status. Climacteric. 2005;8(1):56–62. doi: 10.1080/13697130400013443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao KL, Wood N, Conway GS. Premature menopause and psychological well-being. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21(3):167–174. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harlow BL, Wise LA, Otto MW, et al. Depression and its influence on reproductive endocrine and menstrual cycle markers associated with perimenopause: The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Man MS, MacMillan I, Scott J, et al. Mood, neuropsychological function and cognitions in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychol Med. 1999;29(3):727–733. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Gore R, et al. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in nondemented elderly women: a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):425–430. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunter MS, Whitehead MI. Psychological experience of the climacteric and postmenopause. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;320:211–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koster A, Davidsen M. Climacteric complaints and their relation to menopausal development: a retrospective analysis. Maturitas. 1993;17(3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(93)90043-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avis NE, Crawford S, Stellato R, et al. Longitudinal study of hormone levels and depression among women transitioning through menopause. Climacteric. 2001;4(3):243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maartens LW, Knottnerus JA, Pop VJ. Menopausal transition and increased depressive symptomatology: a community-based prospective study. Maturitas. 2002;42(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2, pt 1):230–240. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams J.B, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerber PD, Barrett J, Barrett J, et al. Recognition of depression by internists in primary care: a comparison of internist and "gold standard" psychiatric assessments. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):7–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02596483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(2):99–105. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thibault JM, Steiner RW. Efficient identification of adults with depression and dementia. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(6):1101–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kahn DA, Moline ML, Ross RW, et al. Depression during the transition to menopause: a guide for patients and families. Postgrad Med. 2001:114–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nease DE, Jr., Maloin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract. 2003;52(2):118–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams J.B. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327(7424):1144–1146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(1):41–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matthews KA, Wing RR, Kuller LH, et al. Influences of natural menopause on psychological characteristics and symptoms of middle-aged healthy women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(3):345–351. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burger HG, Robertson DM, Baksheev L, et al. The relationship between the endocrine characteristics and the regularity of menstrual cycles in the approach to menopause. Menopause. 2005;12(3):267–274. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000147172.21183.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burger HG, Dudley EC, Robertson DM, et al. Hormonal changes in the menopause transition. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:257–275. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, et al. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(2):414–420. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, et al. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):529–534. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morrison MF, Kallan MJ, Ten Have T, et al. Lack of efficacy of estradiol for depression in postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(4):406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schneider LS, Small GW, Hamilton SH, et al. Estrogen replacement and response to fluoxetine in a multicenter geriatric depression trial. Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5(2):97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schneider LS, Small GW, Clary CM. Estrogen replacement therapy and antidepressant response to sertraline in older depressed women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amsterdam J, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, et al. Fluoxetine efficacy in menopausal women with and without estrogen replacement. J Affect Disord. 1999;55(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hersh AL, Stefanick M.L, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, et al. Gender differences in treatment response to sertraline versus imipramine in chronic depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1445–1452. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pinto-Meza A, Usall J, Serrano-Blanco A, et al. Gender differences in response to antidepressant treatment prescribed in primary care: does menopause make a difference? J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1-3):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thase ME, Entsuah R, Cantillon M, et al. Relative antidepressant efficacy of venlafaxine and SSRIs: sex-age interactions. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14(7):609–616. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cohen L, Kornstein S, Entsuah R. Puerto Rico: San Juan; Age and gender differences in antidepressant treatment: a comparative analysis of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Poster presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. December 12–16, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burt VK, Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, et al. Duloxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder in women ages 40 to 55 years. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(4):345–354. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Leskela US, et al. Severity and comorbidity predict episode duration and recurrence of DSM-IV major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(6):810–819. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burt VK, Altshuler LL, Rasgon N. Depressive symptoms in the perimenopause: prevalence, assessment, and guidelines for treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1998;6(3):121–132. doi: 10.3109/10673229809000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hunter MS. Psychological and somatic experience of the menopause: a prospective study. (corrected) Psychosom Med. 1990;52(3):357–367. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collins A, Landgren BM. Reproductive health, use of estrogen and experience of symptoms in perimenopausal women: a population-based study. Maturitas. 1994;20(2-3):101–111. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woods NF, Smith-Dijulio K, Percival DB, et al. Depressed mood during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Menopause. 2008;15(2):223–232. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181450fc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bosworth HB, Bastian L.A, Kuchibhatla MN, et al. Depressive symptoms, menopausal status, and climacteric symptoms in women at midlife. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):603–608. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Jr., Gerety MB, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(12):913–921. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]