Abstract

Pathological gambling is a widespread problem with major implications for society and the individual. There are effective treatments, but little is known about the relative effectiveness of different treatments. The aim of this study was to test the effectiveness of motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and a no-treatment control (wait-list) in the treatment of pathological gambling. This was done in a randomized controlled trial at an outpatient dependency clinic at Karolinska Institute (Stockholm, Sweden). A total of 150 primarily self-recruited patients with current gambling problems or pathological gambling according to an NORC DSM-IV screen for gambling problems were randomized to four individual sessions of motivational interviewing (MI), eight sessions of cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT), or a no-treatment wait-list control. Gambling-related measures derived from timeline follow-back as well as general levels of anxiety and depression were administered at baseline, termination, and 6 and 12 months posttermination. Treatment showed superiority in some areas over the no-treatment control in the short term, including the primary outcome measure. No differences were found between MI and CBGT at any point in time. Instead, both MI and CBGT produced significant within-group decreases on most outcome measures up to the 12-month follow-up. Both forms of intervention are promising treatments, but there is room for improvement in terms of both outcome and compliance.

Keywords: gambling, motivational interviewing, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), psychotherapy outcome

Pathological gambling is a widespread problem with major implications for society and the individual (Kessler et al., 2008). However, according to a recent meta-analysis, there are effective psychological treatments for pathological gambling (Pallesen, Mitsem, Kvale, Johnsen, & Molde, 2005). Specifically, it was concluded that treatments were more effective than no-treatment control conditions, and that the overall effect size was large at both posttreatment (Cohen's d = 2.01) and follow-up (d = 1.59). However, interpreting and generalizing the findings is complicated because most studies included were either single-group designs with pre-post measurements or an active treatment versus an inactive no-treatment control. Hence, little is known about the relative effectiveness of different treatments. From the meta-analysis, we know that individual cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), CBGT, self-help, aversive therapy, eclectic therapy based on Gamblers Anonymous, imaginal desensitization, and imaginal relaxation all render medium to large effect sizes. However, little is known about MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) as a single treatment for pathological gambling.

MI is a treatment approach that has promising results on other dependency disorders, such as alcohol consumption (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005) and drug use (Rubak, Sandbæk, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005). In brief, MI consists of a skilled style of counseling for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence. It includes showing empathy, developing discrepancy between current behavior and an alternative lifestyle behavior, reinforcing the patient's sense of self-efficacy and rolling with the client's resistance to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI is typically provided as a brief intervention, within one to four sessions (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003). An adaption of MI, to give the client feedback on an earlier examination, referred to as motivational enhancement therapy (MET), has been tested as an adjunct to other treatments of pathological gambling. For example, Hodgins et al. (Hodgins, Currie, & el-Guebaly, 2001; Hodgins, Currie, el-Guebaly, & Peden, 2004) found that adding 20 to 45 min of telephone-administered MET to a self-help book treatment had a significant advantage compared with only self-help book treatment both at posttest and at 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups. Carlbring and Smit (2008) replicated these findings up to 36 months after treatment in a similar study, with the difference being that they provided the treatment as an Internet-based self-help program with telephone support. In addition, in Petry, Weinstock, Ledgerwood, and Morasco's (2008) exploration of the efficacy of MET, participants were randomized to an assessment-only control, brief advice, one session of MET, or one session of MET plus three sessions of CBT. Again, the MET was a restricted and brief intervention, lasting on average only 50 min. It included personalized feedback followed by exploration of the positive and negative consequences of gambling and the participant's goals and values. In contrast to the Hodgins studies, the results were less straightforward. Although participants treated with MET or MET plus CBT improved, so did those who were only assessed to a large extent. In sum, there is some evidence in support of MET. However, to our knowledge, there has not been any randomized trial on a more comprehensive MI treatment program for pathological gambling. The purpose of the present study was, therefore, to compare the effectiveness of eight sessions of CBGT with four sessions of individual MI. To control for spontaneous remission, a no-treatment control group was included in the initial phase.

Method

Design

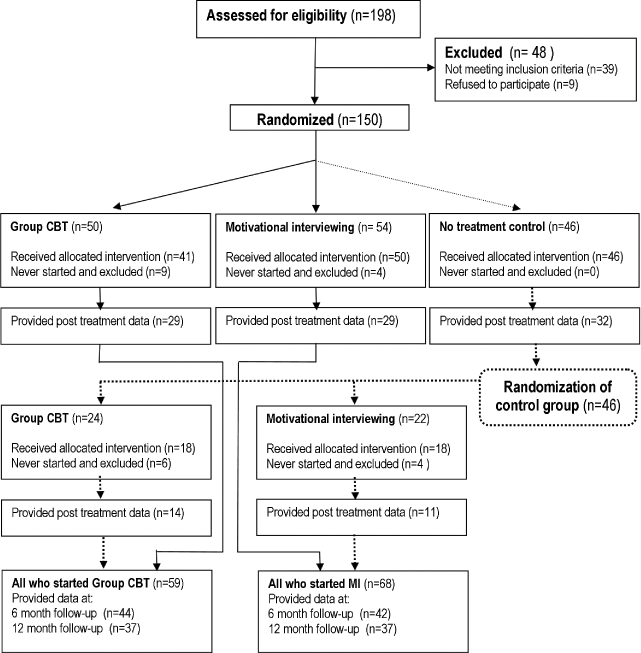

As outlined in the CONSORT flowchart in Figure 1, the study was designed as a randomized controlled trial with three parallel groups with measurements at baseline and 9 weeks. After 9 weeks, the no-treatment control group received the allotted treatment, and participants were included in the two active treatment arms. The intervention groups were subjected to two prolonged follow-ups at 6 and 12 months. The intervention was provided at no cost, and participation was voluntary. The only compensation that was provided was two movie theater tickets per occasion for completing the posttreatment and follow-up measures.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of study participants, point of random assignment, and drop-outs at each stage.

Based on the most recent meta-analysis of treatment outcomes on pathological gambling (Pallesen et al., 2005), a large effect size was anticipated between treatment and the no-treatment control (Cohen's d = 0.80). However, between the two active treatments, we expected a small effect because it has been shown that group treatment is somewhat less effective than individual treatment (Dowling, Smith, & Thomas, 2007). Instead, we powered the comparisons between the two active treatments as a noninferiority trial (Piaggio, Elbourne, Altman, Pocock, & Evans, 2006). We assumed that a mean standardized difference (Cohen's d) of ≧ 0.50 would be of clinical value (medium effect size according to Cohen, 1988). This would necessitate a group size of 128 to achieve a power of 0.80 to detect a significant difference in a two-tailed test at the conventional α < .05. Thus, the study was adequately powered.

Recruitment and participants

To recruit 150 patients who were willing to be randomized, 198 patients went through a 60- to 90-min in-person interview at an outpatient dependency clinic between June 2005 and December 2006. The interview was conducted by a clinical psychologist and was partly based on the structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling (Grant, Steinberg, Kim, Rounsaville, & Potenza, 2004) adapted for Swedish use. It also included timeline follow-back (Weinstock, Whelan, & Meyers, 2004), demographic questions, and a set of self-report measures described shortly.

Exclusion criteria included suicidal ideation (n = 13), unwillingness to be randomized (n = 6), recently commenced medication for anxiety and/or depression or being in a parallel treatment for gambling problems (n = 6), not having an ongoing gambling problem (n = 5), primary drug and/or alcohol dependence (n = 4), ongoing severe depression (n = 3), unwillingness to participate (n = 3), ongoing bipolar disorder (n = 2), imprisonment (n = 2), inability to speak Swedish (n = 2) or complete self-report questionnaires (n = 1), and ongoing psychosis (n = 1).

Randomization was conducted by a true random-number service independent of the investigators and therapists. Participants randomly selected an envelope, the contents of which indicated their assigned condition. For natural reasons, participants could not be blind to conditions. Of the 150 patients who were randomized, 23 participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria but did not start treatment for various reasons (MI: n = 8; CBGT: n = 15). The difference between groups was not significant (two-sided Fisher's exact p = 0.12). Only the participants who attended at least one session were included in the analysis (n = 127).

The sample included 21 (16.5%) women and 106 (83.5%) men; 84 (66%) were native Swedes, and 65 (51.2%) had at least one parent who was born in another country. At the time of the initial interview, the mean age of the participants was 40.5 years (SD = 12.3). Most of the 127 participants were self-referred (69.3%); the remaining were encouraged by significant others or other contacts to seek help. The average number of years with self-reported gambling problems was 7.1 (SD 8.3). Inspite of this, most participants had not sought any previous treatment for their gambling problem. However, 56 (44.1%) had received previous treatment but 42 (75%) had been unhappy with it.

The most frequent primary problematic game for the 127 participants was state-sanctioned video lottery terminals in restaurants (37.8%), at legal casinos (7.1%), or at unregulated clubs (2.4%). Poker on the Internet (15.7%) and various types of horse betting (13.4%) were also common. Classic casino-type games at casinos (6.3%) or restaurants (3.1%) were less frequent. The gambling had resulted in current debts for 85% (n = 108) of the participants, with an average amount of $40,436 (US) (SD = $128,619; mdn = $12,043) due. Most participants described their financial status as very bad (53.5%, n = 68) or bad (16.5%, n = 21). Only 3.2% (n = 4) judged it to be very good or good (11.8%, n = 15), whereas 15% (n = 19) described it as neither good nor bad.

Participants reported their education as follows: university education, 31 (24.4%); 9-year compulsory primary school, 25 (19.7%); secondary school, 71 (55.9%). Most participants either had a job (n = 81 [63.8%]) or were students (5 [4%]), whereas 37 were unemployed (14.1%) or on sick leave (14.9%). The remaining were either retired (n = 3 [2.4%]) or “miscellaneous” (n = 1 [0.8%]). Most participants were living alone with children (n = 45 [35.4%]) or without children (n = 14 [11%]), 28 (22%) were cohabiting with a partner with children, and 25 (19.7%) had a joint household with their partner but without children. The rest (n = 15 [11.9%]) typically lived with friends or parents. About 33% of the participants had at least one child younger than age 18.

The study was approved by the regional ethical committee at Karolinska Institute and was subsequently registered in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN92322614).

Outcome measures

The NORC DSM-IV Screen for gambling problems (NODS; Gerstein et al., 1999), modified to assess gambling at 1 month instead of 1 year, was used as the primary outcome measure. The use of NODS instead of the more widely-used South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987) was motivated by the fact that the NODS uses Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition [DSM-IV]; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) criteria as opposed to the SOGS, which is based on the third edition (APA, 1980). Furthermore, the NODS has been reported to show promise as an outcome measure of gambling problems (Hodgins, 2004; Wickwire, Burke, Brown, Parker, & May, 2008). In addition, measures derived from timeline follow-back (Weinstock et al., 2004), Beck Depression Inventory-2 (BDI-2; Beck & Steer, 1996), and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988) constituted the secondary outcome measures. Finally, participants were given a five-item, 10-point treatment credibility scale adapted from Borkovec and Nau (1972). This was done at the end of the interview, after they had received a full description of the two methods.

Treatments

The CBGT treatment (n = 59) was administered in closed groups with one 3-hr session per week for 8 weeks. When time for scheduled coffee breaks and short bathroom pauses are excluded, the effective therapist time was 135 min/week, totaling 18 hr as a maximum. During the treatment phase, 14 groups were started. The mean number of participants in each group, across all eight sessions, was 3.1 (SD = 1.5). The mean number of therapists per session was 1.7 (SD = 0.5). The unique therapist investment, or cost, was 9.87 hr/participant (total therapist time divided by number of participants attending and number of sessions). In addition to the 8 weeks of treatment, participants were offered participation in an open monthly relapse prevention group. However, only eight of 59 (13.6%) CBGT patients attended at least one of those four booster sessions.

The CBGT treatment was manualized (Ortiz, 2006), and each session focused on a set theme. Psychoeducation, exercises, and homework were included in all sessions. The treatment was partly focused on cognitive restructuring and partly on encouraging clients to try alternative behavioral strategies. In addition, another important treatment component dealt with identifying the personal high-risk situations for gambling and increasing skills to cope with those situations in a better way. A recurrent feature throughout the treatment was to reduce the urge for gambling by imaginary exposure and response prevention. Treatment goals were individually set by each client. Clients were strongly encouraged to refrain from gambling activities during the treatment period. The therapists (one licensed clinical psychologist with psychotherapist training, two licensed clinical psychologists, one licensed social worker, and one licensed psychiatric nurse) received continuous supervision and exclusively provided the treatment in the CBGT condition. All 112 sessions were audiotaped and 22 (20%) were randomly selected to be coded by an independent licensed clinical psychologist with psychotherapist training and experience in the specific treatment method. According to the treatment manual, a total of 375 agenda points should be covered. The result showed a 93% adherence to the manual.

The manualized (Forsberg, Forsberg, & Knifström, 2008) motivational interviewing condition (n = 68) was shorter, on average 50 min per session, but spaced out to cover the same number of weeks as CBGT. The first two sessions were close in time, about 7 days apart. The following two sessions had an average of 3 to 4 weeks between them. The sessions used standard MI principles (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and explored the positive and negative consequences of gambling, including mapping the reasons for gambling. Finally, the patient was encouraged to make a decision about gambling. If matching patient readiness to change status, the patient was encouraged to make a decision about gambling as well as a change plan. Because the MI sessions were delivered one-on-one, only one patient was treated at the time. The total therapist time, or cost, per patient was 2.45 hr in total since the average patient attended a total of 2.94 (SD = 1.08) sessions.

The therapists (one licensed clinical psychologist with psychotherapist training and 20 years MI experience, one licensed clinical psychologist with 2 years clinical MI experience, and two licensed social workers, one of whom one 10 years experience and the other was newly trained in MI) supervised themselves as a group once a month based on assessing their own audiotaped sessions, using the results from the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Code 2.0 (MITI; Forsberg, Källmén, Hermansson, Berman, & Helgason, 2007) to facilitate specific feedback (Bennett, Roberts, Vaughan, Gibbins, & Rouse, 2007; Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2008). They exclusively delivered the treatment in the MI condition. To test the integrity of the MI (Forsberg et al., 2008), all 200 sessions were audiotaped and 40 (20%) were randomly selected to be coded according to MITI by one of four independent and blinded coders. The following subvariables of the MITI were observed (values are means, with proportion of competency in sessions in parenthesis): global empathy M = 5.45 (88% of all MI sessions above reference value 5) and global MI spirit M = 5.38 (80% above reference value 5), with no value below 4 in any session for the two global values; ratio reflections to questions M = 4.72 (100% above reference value 1.0); ratio open questions/total questions M = 0.34 (45% above reference value 0.50); complex reflections/total reflections M = 0.59 (90% above reference value 0.40); and MI-adherent statement/MI-adherent and not MI-adherent statements M = 0.80 (75% above reference value 0.90). The MI competency in the delivered sessions is considered good (Moyers, Martin, Manual, & Miller, 2003), with almost complete fulfillment of the given reference values for MI proficiency in the coding manual.

Statistical analyses

A mixed-effect model approach (Gueorguieva & Krystal, 2004) was used because in the analysis of longitudinal data repeated observations for the same individual are correlated. This correlation violates the assumption of independence necessary for more traditional, repeated measure analysis and leads to bias in regression parameters. Typically, ignoring the correlation of observations leads to smaller standard errors and increases the likelihood for significant differences when there are none, which might lead to the wrong conclusion (Brown & Prescott, 1999; Gueorguieva & Krystal, 2004). Furthermore, mixed-effect models are able to accommodate missing data and the integration of time-varying factors, which are issues in the present study.

To compare CBGT and MI according to the outcome measures at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months and to compare the effect of immediate treatment compared with waiting 3 months, we used a covariance pattern model (Brown & Prescott, 1999), which is a special case of mixed-effects models. A separate model was estimated for each of the 13 outcome factors, listed in Tables 1 and 2. The variance–covariance for each model was assumed to be block diagonal but unstructured within a block defined by participants. To study whether the effect of treatment differed across the time points, we tested the interaction between time and treatment. We used the restricted maximum likelihood as our model estimation method and present the estimated means and difference between treatments and their respective standard error means. All participants who attended at least one MI or GCBT session are included in the analysis. All analysis was performed in SPSS version 16.0.1 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Table 1.

Comparisons between motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral group therapy vs. no-treatment control at pre- and posttreatment

| Measure/time | Estimatesa | p(time) | Treatment differenceb | p (difference) | p (Time × Treatment) |

| NODS | .036∗ | ||||

| Pre | 5.5 (0.2) | .000 | 0.53 (0.5) | .241 | |

| Post | 3.0 (0.3) | −0.88 (0.6) | .165 | ||

| Days gambled in past 30 days | .218 | ||||

| Pre | 11.5 (0.9) | .094 | 2.3 (1.9) | .215 | |

| Post | 9.1 (1.3) | −1.1 (2.5) | .659 | ||

| Days binge gambling | .547 | ||||

| Pre | 4.8 (0.7) | .000 | 1.3 (1.4) | .351 | |

| Post | 1.8 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.8) | .664 | ||

| Minutes spent on gambling in past 30 days | .277 | ||||

| Pre | 1976 (234) | .571 | 227 (469) | .629 | |

| Post | 1760 (408) | 1063 (817) | .201 | ||

| Dollars wagered in past 30 days | .866 | ||||

| Pre | 2347 (431) | .009 | 249 (862) | .773 | |

| Post | 1055 (227) | 84 (453) | .853 | ||

| Win/lost | .766 | ||||

| Pre | –1293 (232) | .003 | 22 (463) | .962 | |

| Post | – 579 (183) | 157 (366) | .670 | ||

| Typical gambling day ($) | .431 | ||||

| Pre | 245 (33) | .000 | – 74 (67) | .272 | |

| Post | 90 (14) | –18 (28) | .533 | ||

| Typical gambling day (minutes) | .390 | ||||

| Pre | 177 (14.8) | .001 | –10.6 (29.7) | .722 | |

| Post | 101 (18.2) | 27.1 (36.4) | .460 | ||

| BDI-2 | .036∗ | ||||

| Pre | 24.1 (1.0) | .000 | 3.2 (2.1) | .127 | |

| Post | 17.6 (1.4) | −2.0 (2.7) | .461 | ||

| BAI | .225 | ||||

| Pre | 18.3 (1.0) | .000 | 1.4 (2.1) | .505 | |

| Post | 13.3 (1.3) | −1.8 (2.6) | .496 | ||

| Planned money to bet | .644 | ||||

| Pre | 1281 (396) | .232 | 423 (792) | .594 | |

| Post | 764 (184) | 24 (367) | .949 | ||

| Number of drinks/gambling day | .756 | ||||

| Pre | 0.65 (0.13) | .421 | −0.45 (0.26) | .084 | |

| Post | 0.53 (0.17) | −0.36 (0.30) | .303 | ||

| Intoxicated gambling days | .136 | ||||

| Pre | 1.1 (0.24) | .840 | 0.29 (0.48) | .553 | |

| Post | 1.1 (0.38) | −0.82 (0.77) | .291 |

Note. NODS = NORC DSM-IV Screen for Gambling Problems; BDI-2 = Beck Depression Inventory-2; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

aValues represent M ± SE.

bMotivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral group therapy vs. no-treatment control (wait list). Values represent M ± SE.

∗p < .05.

Table 2.

Comparisons between motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral group therapy at pre- and posttreatment and 6- and 12-month follow-up

| Measure/time | Estimatesa | Significant pairwise comparisonsb | Treatment differencec | P(difference) | P (Time × Treatment) |

| NODS | .108 | ||||

| Pre | 5.5 (0.2) | Pre > post, 6 & 12 mo | 0.6 (0.4) | .188 | |

| Post | 2.1 (0.3) | −0.8 (0.6) | .170 | ||

| 6 mo | 2.4 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.6) | .821 | ||

| 12 mo | 2.0 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.6) | .553 | ||

| Days gambled in past 30 days | .583 | ||||

| Pre | 12.0 (0.9) | Pre > post, 6 & 12 mo | −1.2 (1.8) | .502 | |

| Post | 8.0 (1.5) | – 2.4 (3.1) | .436 | ||

| 6 mo | 8.4 (1.1) | 1.6 (2.2) | .459 | ||

| 12 mo | 7.6 (1.0) | 0.9 (2.0) | .664 | ||

| Days binge gambling | .539 | ||||

| Pre | 4.9 (0.7) | Pre > post, 6 & 12 mo | 0.4 (1.3) | .769 | |

| Post | 2.2 (0.4) | Post > 12 mo | 0.5 (0.8) | .544 | |

| 6 mo | 2.6 (0.6) | 6 mo > 12 mo | −0.3 (1.3) | .799 | |

| 12 mo | 1.0 (0.3) | −0.5 (0.6) | .417 | ||

| Minutes spent on gambling in past 30 days | .999 | ||||

| Pre | 2028 (232) | Pre > 6 & 12 mo | −17.5 (463) | .970 | |

| Post | 2464 (546) | Post > 6 & 12 mo | −10.1 (1092) | .993 | |

| 6 mo | 984 (187) | 6.6 (374) | .986 | ||

| 12 mo | 840 (157) | 36.5 (314) | .908 | ||

| Dollars wagered in past 30 days | .265 | ||||

| Pre | 2400 (405) | Pre > post, 12 mo | 1337 (809) | .101 | |

| Post | 1081 (243) | – 324 (486) | .513 | ||

| 6 mo | 1520 (541) | – 377 (1081) | .728 | ||

| 12 mo | 940 (282) | – 588 (564) | .301 | ||

| Win/lost | .304 | ||||

| Pre | −1351 (228) | Pre < post, 6 & 12 mo | – 862 (455) | .061 | |

| Post | – 589 (211) | −174 (422) | .683 | ||

| 6 mo | – 565 (187) | 115 (374) | .759 | ||

| 12 mo | – 675 (216) | 250 (432) | .566 | ||

| Typical gambling day ($) | .847 | ||||

| Pre | 232 (33) | Pre > post, 6 mo | 69(66) | .294 | |

| Post | 101 (14) | 17 (28) | .550 | ||

| 6 mo | 149 (24) | 6 mo > post | 5 (48) | .914 | |

| 12 mo | 206 (53) | 12 mo > post | 52 (105) | .622 | |

| Typical gambling day (minutes) | .337 | ||||

| Pre | 173 (15) | Pre > 6 mo | – 24.7 (29.0) | .397 | |

| Post | 128 (22) | 62.6 (44.6) | .172 | ||

| 6 mo | 103 (16) | 2.1 (32.0) | .949 | ||

| 12 mo | 131 (24) | – 4.3 (47.7) | .929 | ||

| BDI-2 | .196 | ||||

| Pre | 24.4 (1.1) | Pre > post, 6 & 12 mo | 1.7 (2.1) | .425 | |

| Post | 14.3 (1.2) | – 3.9 (2.4) | .112 | ||

| 6 mo | 13.7 (1.1) | −1.2 (2.3) | .613 | ||

| 12 mo | 12.1 (1.4) | −1.5 (2.8) | .602 | ||

| BAI | .323 | ||||

| Pre | 18.7 (1.0) | Pre > post, 6 & 12 mo | 2.0 (2.1) | .346 | |

| Post | 11.0 (1.2) | – 2.7 (2.4) | .248 | ||

| 6 mo | 10.2 (1.0) | 0.3 (2.0) | .886 | ||

| 12 mo | 10.4 (1.2) | −0.5 (2.3) | .835 | ||

| Planned money to bet ($) | .275 | ||||

| Pre | 1,339 (370) | No differences | 951 (741) | .202 | |

| Post | 768 (191) | −177 (382) | .645 | ||

| 6 mo | 766 (252) | – 227 (505) | .655 | ||

| 12 mo | 585 (196) | – 626 (393) | .117 | ||

| Number of drinks/gambling day | .610 | ||||

| Pre | 0.57 (0.13) | No differences | 0.06 (0.27) | .809 | |

| Post | 0.89 (0.32) | 0.84 (0.63) | .195 | ||

| 6 mo | 0.72 (0.23) | −0.14 (0.47) | .773 | ||

| 12 mo | 0.85 (0.29) | 0.35 (0.59) | .554 | ||

| Intoxicated gambling days | .155 | ||||

| Pre | 1.3 (0.24) | No differences | 0.01 (0.48) | .988 | |

| Post | 1.0 (0.37) | 1.44 (0.73) | .055 | ||

| 6 mo | 0.84 (0.18) | 0.14 (0.37) | .709 | ||

| 12 mo | 0.85 (0.24) | −0.11 (0.48) | .820 |

Note: NODS = NORC DSM-IV Screen for gambling problems; BDI-2 = Beck Depression Inventory-2; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

aValues represent M ± SE.

bp < .05 (time).

cCognitive behavioral group therapy vs. motivational interviewing.

Results

Pretreatment measures and credibility

There were no significant differences between the two treatments conditions and the no-treatment control group at the baseline assessment on any measure or demographic variable. To be able to draw unequivocal conclusions about differences between treatment groups, it is essential that the groups are equivalent as to the credibility perceived in the treatment methods they receive. The scores for the credibility ratings were summed across the five items, resulting in a single score with a possible range of 0 to 50. Five participants failed to answer the questions. Hence, the analysis is based on the answers from 122 patients. The average estimate of the treatment's credibility on the Treatment Credibility Scale (Borkovec & Nau, 1972) was moderate to high, with a mean score of 37.2 (SD = 9.5) for the CBGT condition and 38.1 (SD = 9.4) for the MI, a nonsignificant difference, t(121) = 0.87, p = .39.

Attrition

Even though automatic SMS reminders were sent out to the participants’ cellular phones the day before each of the MI or CBGT sessions throughout the entire treatment, compliance was generally low. In CBGT the average number of attended sessions was 5.6 (SD = 2.3). Hence, the average dose was 70%. The frequency of session participation among the 59 individuals who started CBGT treatment is as follows: one session, 100%; two, 91.5%; three, 81.4%; four, 81.4%; five, 71.2%; six, 62.7%; seven, 45.8%; eight, 28.8%. Among the reasons for not attending all sessions or for dropping out, were not liking being in a group treatment, lack of motivation, or practical issues such as having the flu or difficulty traveling to treatment, including lack of time.

In the MI condition, numbers are slightly, but not significantly, higher: 29 (42.6%) patients attended all four treatment sessions (two-sided Fisher's exact p = .14). In addition, the proportion of participants attending at least one session did not differ between the two treatment conditions (two-sided Fisher's exact p = .12). The frequency of session participation among the 68 individuals who started MI treatment is as follows: one session, 100%; two, 88.20%; three, 63.2%; four, 42.6%. The average number of sessions was 0.9 (SD = 1.1). Hence, the average dose was 72.5%. Lack of motivation and practical difficulties coming to treatment were among reasons for missing sessions or discontinuing. The drop-outs did not differ significantly from the completers on any demographic or pretreatment measure.

Outcome

As evident from Table 1, which presents the immediate results of treatment versus no-treatment control, there was a significant Time × Treatment interaction for the primary outcome measure (NODS) and for one of the secondary measures (BDI-2).

There were no other measures indicating the superiority of treatment over no-treatment control. Hence, the frequency, time, and amount of money spent on gambling were not dependent on treatment; neither was general level of anxiety or alcohol consumption in relation to gambling.

However, there were clear time effects for a number of outcome measures for the whole study population, including general level of anxiety and depression, days binge gambling, total amount wagered, as well as less money lost gambling. In addition, a typical gambling day lasted a shorter period and the total amount spent on a typical gambling day was lower. No time effects were observed for the number of days or total time spent on gambling in the past 30 days. The frequency and magnitude of alcohol use in combination with gambling were also unchanged.

As seen in Table 2, there are no significant Time × Treatment interactions, indicating that there were no differences in relative effects between the two active treatments at any time. However, both treatments generally yielded significant pre- to posttreatment effects that were maintained or continued to improve. Specifically, the primary outcome measure (NODS) showed a significant reduction that was maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Also improved was the number of days gambled in the past 30 days, including binge gambling, and the amount of time and money spent as well as net cost. In addition, depression and anxiety levels dropped. However, the number of days gambling while intoxicated and the number of drinks consumed while gambling did not decrease. Neither did the fixed predetermined amount of money intended to be spent on gambling.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to compare the effectiveness of CBGT and MI. It was expected that both treatments would do better than no-treatment control, and that the effects of both treatments would be maintained at the 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments. As expected, there was a significant difference between treatment versus no-treatment control on the primary outcome measure as well as on one of the secondary outcome measures. However, given the relatively large sample size, it was expected that more secondary outcome measures should show improvement. The explanation could be a combination of natural recovery (Slutske, 2006) and the possibility that once a person has decided that he or she has a problem so severe that it requires professional treatment, he or she is more or less determined to stop and can sometimes do so by him- or herself (Petry, 2005). Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that a thorough in-person assessment interview might be what is needed for a person to stop gambling. This is not the first study to report similar results. In fact, when active treatment is compared with no-treatment control, the literature frequently shows that no-treatment control can be rather effective, at least in the short term (Hodgins et al., 2001). Unfortunately, because people on the wait-list, for ethical reasons, received treatment before the follow-up data were collected, there is no between-group comparison at follow-up. Hence, the robustness of the no-treatment control findings is unknown. The phenomenon that patients often do change in the very early phase of treatments, without having had much exposure to what is supposed to be effective ingredients in the treatments, is repeatedly reported in the field of alcohol use (Bien, Miller, & Tonigan, 1993; Stout et al., 2003).

When looking at the relative effectiveness of CBGT versus MI, no significant results emerged. Instead, both treatments showed improvements in most of the areas, including the primary outcome measure and several gambling-related domains. In addition, the level of depression decreased from a moderate to a mild level at posttreatment and 6-month follow-up, which then continued to decrease to reach a minimal level at 12 months. Hence, treatment allocation did not seem to influence outcome. However, in real life not everyone accepts randomization, which hampers the generalization of the results to a wider population. It could be that treatment preferences interact with the outcome, and by necessity randomization results in potential mismatches between the preferred treatment and the actual treatment received.

On a group level, there were no differences in treatment credibility. However, on an individual level some participants refused group therapy, while others preferred group treatment. Hence, future studies could investigate outcome in relation to receiving the preferred treatment. On the other hand, preferences do not always relate to outcome (Leykin et al., 2007). Another obvious comparison would be individual CBT compared with MI, not least because the group format is inappropriate outside urban areas, where few patients are likely to ask for treatment.

Although there were no outcomes favoring one treatment over the other, there was a clear difference in time spent and cost of treatments. CBGT was four times as time-consuming as MI treatment. This was a consequence of difficulties forming groups, which resulted in unusually small groups. Hence, had the groups been filled as intended, the cost per patient would have been equivalent.

It could be argued that the treatments were delivered by incompetent clinicians, which, in turn, reduced the effectiveness of one or both treatments. However, when using the MITI as a tool for assessing MI competence, nearly all sessions were assessed above reference values given. In addition, the MITI is known for having high standards (Bennett et al., 2007; Mash et al., 2008), and we know that high MI proficiency is needed to make client responses predicting behavior change outcomes (Forsberg et al., 2008; Martino et al., 2008). Thus, the MI treatment seems to be delivered competently. In the CBGT, only the quantity, not the quality, of the delivered treatment was measured. Thus, we have somewhat less knowledge about the CBGT competency in the sessions. However, high motivation and competence were present. In addition, one CBGT therapist had authored the treatment manual.

In summation, MI and CBGT treatments showed superiority in some areas over the no-treatment control in the short term, and both MI and CBGT demonstrated promising within-group results on most outcome measures up to the 12-month follow-up.

Acknowledgments

The Swedish National Institute of Public Health is acknowledged for funding this study. We thank the following individuals for their involvement in the project: Anders Stymne, Anna Lehndal, Annika Sonnenstein, Frida Fröberg, Helena Lindqvist, Jenny Jakobsson, Kerstin Forsberg, Kristina Sundkvist, Lars Bergström, Liria Ortiz, Marie Risbeck, Owe Berglind, Peter Wirbing, and Torbjörn Sjölund.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1980. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G., Steer R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A. Fagernes Norway: Psykologiförlaget AB; 1996. Beck Depression Inventory. Manual (Swedish version) [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G.A., Roberts H.A., Vaughan T.E., Gibbins J.A., Rouse L. Evaluating a method of assessing competence in motivational interviewing: A study using simulated patients in the United Kingdom. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien T.H., Miller W.R., Tonigan J.S. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction. 1993;88(3):315–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec T.D., Nau S.D. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Brown H., Prescott R. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. Applied mixed models in medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Burke B.L., Arkowitz H., Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P., Smit F. Randomized trial of Internet delivered self-help with telephone support for pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:1090–1094. doi: 10.1037/a0013603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling N., Smith D., Thomas T. A comparison of individual and group cognitive-behavioural treatment for female pathological gambling. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(9):2192–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L., Forsberg K., Knifström E. Stockholm: Statens Folkhälsoinstitut; 2008. Motiverande samtal vid skadligt spelande och spelberoende [Motivational interviewing for at risk and pathological gambling] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L., Källmén H., Hermansson U., Berman A., Helgason A. Coding counsellor behaviour in motivational interviewing sessions: Inter-rater reliability for the Swedish Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI) Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36(3):162–169. doi: 10.1080/16506070701339887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein D.S., Murphy M., Toce J., Hoffmann A., Palmer R., Johnson C., et al. Chicago: National Gambling Impact Study Commission; 1999. Gambling impact and behaviour. [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.E., Steinberg M.A., Kim S.W., Rounsaville B.J., Potenza M.N. Preliminary validity and reliability testing of a structured clinical interview for pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research. 2004;128(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R., Krystal J.H. Move over ANOVA: Progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J., Steele J., Miller W. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C. Using the NORC DSMScreen for Gambling Problems as an outcome measure for pathological gambling: Psychometric evaluation. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(8):1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Currie S.R., el-Guebaly N. Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(1):50–57. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Currie S., el-Guebaly N., Peden N. Brief motivational treatment for problem gambling: A 24-month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(3):293–296. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Hwang I., Labrie R., Petukhova M., Sampson N.A., Winters K.C., et al. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(9):1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H.R., Blume S.B. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): Anew instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(9):1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leykin Y., DeRubeis R.J., Gallop R., Amsterdam J.D., Shelton R.C., Hollon S.D. The relation of patients’ treatment preferences to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S., Ball S.A., Nich C., Frankforter T.L., Carroll K.M. Community program therapist adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(1-2):37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash R., Baldassini G., Mkhatshwa H., Sayeed I., Ndapeua S., Mash B. Reflections on the training of counsellors in motivational interviewing for programmes for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. South African Family Practice. 2008;50(2):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Rollnick S. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T., Martin T., Manual J., Miller W. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 2003. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz L. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur; 2006. Till spelfriheten! Kognitiv beteendeterapi vid spelberoende [CBT for pathological gambling] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S., Mitsem M., Kvale G., Johnsen B.-H., Molde H. Outcome of psychological treatments of pathological gambling: A review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1412–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M. Stages of change in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(2):312–322. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Weinstock J., Ledgerwood D.M., Morasco B. A randomized trial of brief interventions for problem and pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):318–328. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaggio G., Elbourne D.R., Altman D.G., Pocock S.J., Evans S.J. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: An extension of the CONSORT statement. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1152–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S., Sandbæk A., Lauritzen T., Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W.S. Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two U.S. national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):297–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout R., Del Boca F., Carbonari J., Rychtarik R., Litt M., Cooney N. Babor T., Del Boca F. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. Primary treatment outcomes and matching effects: Outpatients arm. Treatment matching in alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock J., Whelan J.P., Meyers A.W. Behavioral assessment of gambling: An application of the timeline followback method. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16(1):72–80. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickwire E.M., Jr., Burke R.S., Brown S.A., Parker J.D., May R.K. Psychometric evaluation of the National Opinion Research Center DSM-IV Screen for Gambling Problems (NODS) American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(5):392–395. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]