Abstract

We report a single-step, single reagent, label-free, isothermal electrochemical DNA sensor based on the phenomenon of target-recycling. The sensor exploits strand-specific exonuclease activity to achieve selective enzymatic digestion of target/probe duplexes. This results in a permanent change in the probe structure that yields an increased faradaic current and liberates the intact target molecule to interact with additional detection probes to achieve further signal amplification. Using this architecture, we achieve improved detection limit in comparison to hybridization-based sensors without amplification. We also demonstrate greater than 16-fold amplification of signal at low target concentrations. Combined with the advantages of electrochemical detection and its ready integration with microelectronics, our approach may represent a promising path towards direct DNA detection at the point of care.

Recent years have witnessed the development of DNA biosensors capable of rapid detection of trace amounts of DNA to address increasingly important applications in molecular diagnostics,1, 2 pathogen detection,3-6 forensic investigations7 and environmental monitoring.8-11 Strategies based on the isothermal amplification of signal produced by hybridization events have demonstrated especially great potential for the direct detection of small amounts of DNA with impressive limits of detection (LOD). Examples of such techniques include target-catalyzed transfer reactions for DNA detection,12-14 catalytic silver deposition or stripping assays,15-17 gold nanoparticle (AuNP)-based bio-bar-code assays,18 and enzyme-linked electrochemical assays.19-23 Unfortunately, these methods generally involve multiple assay steps and require the addition of many exogenous reagents. For example, the bio-bar-code assay18 relies on a combination of two-component oligonucleotide-modified AuNPs and single-component oligonucleotide-modified magnetic microparticles, with subsequent detection of amplified bar-code DNA achieved via a chip-based silver deposition assay. Target detection with enzyme-linked, electrochemical sensor15 entails a five-step process involving an enzyme-conjugated secondary probe, enzymatic reduction of p-aminophenyl phosphate, concomitant reductive deposition of silver and, finally, anodic stripping voltammetry to quantify the deposited silver. As such, there is a compelling need for simple, single-step assays for sensitive and specific nucleic acid detection at the point-of-care.

“Target recycling”, wherein signal amplification is achieved by allowing a single DNA target molecule to interact with multiple nucleic acid-based signaling probes, represents an interesting alternative. In this approach, target-probe hybridization catalyzes selective enzymatic digestion of the signaling probe, releasing the intact DNA target to initiate the digestion of other probe molecules, thereby generating multiple signaling events and achieving signal amplification. This approach has previously been demonstrated using exonucleases,24-28 nicking enzymes29, 30 and DNAzymes.31, 32 However, to date, sensor response has been measured predominantly through optical methods (e.g., fluorescence intensity, surface plasmon resonance imaging or capillary electrophoresis). As an alternative, we sought to combine target recycling with electrochemical detection,33-36 which offers numerous advantages for rapid detection including relatively low background, simpler instrumentation and ready integration with microelectronics37, 38—making it a promising detection modality for use in point-of-care settings.

Here we present a single-step, single reagent, isothermal, label-free electrochemical DNA detection assay based on exonuclease/target-catalyzed transformation (ExTCT) of signaling probes bound to the surface of a gold electrode. The assay is designed such that, in the absence of target and exonuclease, the methylene blue (MB)-modified signaling probe assumes a stem-loop structure that sequesters the MB tag away from the electrode, producing a reduced faradaic current. Hybridization of the DNA target to the signaling probe enables selective exonuclease digestion of the target/probe duplex, permanently transforming the probe into a flexible, MB-tagged single-stranded fragment that can efficiently collide with and transfer electrons to the electrode, giving rise to an increased faradaic current. After the digestion of the probe, the target DNA is recycled into solution, allowing hybridization with a new, undigested probe. In this way, a single DNA target can catalyze the transformation of multiple signaling probes, giving rise to an amplified electrochemical signal.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

The DNA signaling probe (1, 5’-PHOS-GATTGAAGTGGATCGGCGTCTCTCCAGGTTT-T(MB)-TTTTTTTTTTTTGACGCCGT-(CH2)6-HS-3’) with 3’ C6-linked thiol, internal methylene blue (MB) label, and 5’ phosphate modification was synthesized by Biosearch Technologies, Inc. (Novato, CA), purified by C18 dual HPLC, and confirmed by mass spectrometry. Here, the underlined sequences represent the complementary bases to the matched target. The 29-base perfectly-matched target (2, 5’-ACCTGGAGAGACGCCGATCCACTTCAATC-3’) and non-cognate target (3, 5’-CTAGTTCTCTCATAATGTAACATGACTAA-3’) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, IA), and purified by HPLC. Tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). 6-mercaptohexanol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Lambda exonuclease (specific activity: 100,000 units/mg; concentration: 5,000 units/ml; extinction coefffiecient: 46,660 cm-1M-1) and its 10× reaction buffer were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). All chemicals were used as received without further purification. 1× reaction buffer for lambda exonuclease contains 67 mM glycine-KOH, 2.5 mM MgCl2 and 50 μg·μL-1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) (pH = 9.4). A phosphate buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 1.0 M NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, pH = 7.2) was prepared and used for all electrochemical measurements.

ExTCT DNA Sensor Preparation

The ExTCT DNA sensor was fabricated by modifying the clean surface of polycrystalline gold disk electrodes (1.6-mm diameter; BASi, West Lafayette, IN) with thiolated probe DNA (1) as detailed in previous work.39 Briefly, the gold electrodes were polished with 1.0-μm diamond polish and 0.05-μm alumina polish (Buehler LTD., Lake Bluff, IL), sonicated in ethanol and deionized (DI) water, and electrochemically cleaned in a series of oxidation and reduction steps in 0.5 M NaOH, 0.5 M H2SO4, 0.01 M KCl/0.1 M H2SO4, and 0.05 M H2SO4. Prior to attachment to the gold surface, the thiolated probe DNA (1) was incubated with 100 mM TCEP for 1 h to reduce disulfide bonds, and subsequently diluted to 1.0 μM with phosphate buffer. The clean gold electrodes were incubated in this reduced probe solution for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The probe-functionalized surface was subsequently passivated with 6 mM 6-mercaptohexanol (diluted in phosphate buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. The electrodes were rinsed with DI water, and stored in phosphate buffer for at least 1 h to equilibrate the probe structures prior to electrochemical measurements.

DNA Target Hybridization, Exonuclease Digestion and Electrochemical Measurements

All electrochemical measurements were performed on a CHI 730 potentiostat (CH Instruments, Austin, TX) in a standard cell with a platinum wire counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (saturated with 3.0 M NaCl). The measurements were conducted with alternating-current voltammetry (ACV) in phosphate buffer using a step potential of 10 mV, amplitude of 25 mV, and a frequency of 10 Hz. The ExTCT sensors were first tested in phosphate buffer to establish the baseline of the MB redox current. The enzymatic reaction buffer consists of 1× lambda exonuclease reaction buffer augmented with MgCl2 (final concentration 10 mM). Reactions were prepared by adding DNA targets and 50 units (0.25 U/μL) of lambda exonuclease to the enzymatic reaction buffer (300 μl of final reaction volume). The ExTCT sensor was then incubated in the reaction solution to allow the surface probe DNA (1) to react with the target DNA and exonuclease in solution. All reactions were conducted in a 37 °C water-bath in the dark for 1 h (except for the time-course study). After the reaction, the sensor was switched to phosphate buffer and allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for at least 20 minutes prior to measurements. The signal gain in MB redox current was determined as the relative difference between the baseline and post-incubation redox currents. Relative sensor response (%) was employed in the interest of reproducibility. Of note, the present ExTCT sensor architecture is designed for single-use; therefore, multiple electrodes were used to collect the various data sets presented in this work.

Time-Course Response Experiments

Measurements were taken after 10, 30, 60, and 120 minutes of enzymatic reaction. At each time point, the sensor was switched to the phosphate buffer to equilibrate at room temperature for 20 minutes prior to ACV measurements. After measurement, the sensor was returned to the same reagent-containing reaction solution to continue the enzyme reaction. All other reaction conditions and reagents in the time course response experiments were the same as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design of ExTCT DNA Sensor

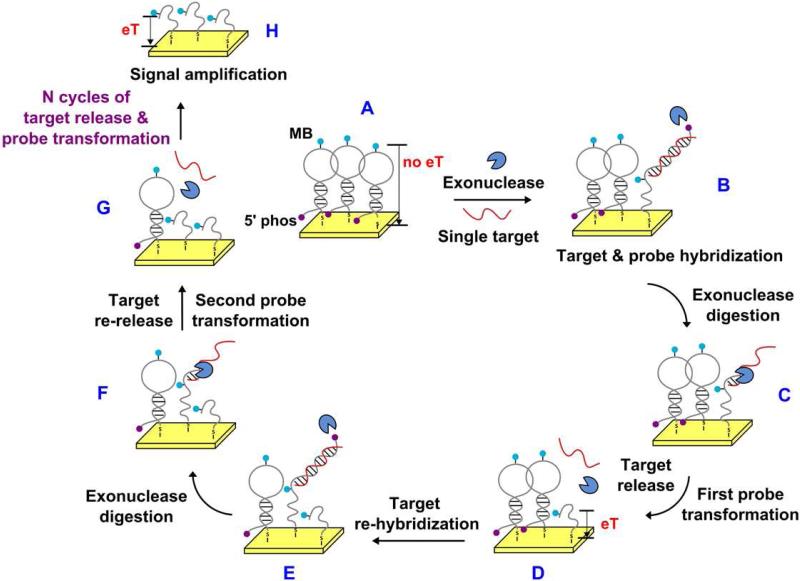

The ExTCT probe (1) consists of a 52-nucleotide (nt) DNA strand that has been modified with a thiol group at its 3’ terminus and a phosphate group at its 5’ terminus, and contains an MB tag at an internal position. In the absence of target, the probe self-hybridizes into a stem-loop structure consisting of a 7-base-pair (bp) stem and 25-nt loop, with the MB situated at the center of the loop. Signaling current arises from electron transfer between the MB redox tag and the gold electrode surface (Figure 1), and the magnitude of the faradaic current depends on the configuration of the probe. In the absence of target, the rigid stem-loop probe configuration fixes the MB tag away from the electrode, generating a relatively small faradaic current (Figure 1, Step A), presumably arising due to limited, long-range electron transfer from MB to the electrode40 or due to short-range electron transfer from the probes which are not in the stem-loop conformation. Upon addition of target DNA (29-nt) and lambda exonuclease (Figure 1, Step B), the target DNA hybridizes with the signaling probe to form a 29-bp DNA duplex at the 5’ end, while the 3’ end retains a 23-nt single-stranded structure. The lambda exonuclease41-43 in turn preferentially binds to the duplex region and selectively hydrolyzes the 5’ phosphate-modified probe strand in the 5’-to-3’ direction (Figure 1, Step C), with digestion terminating after the duplex is fully consumed. The probe is thereby transformed into a flexible 23-nt single-stranded fragment with MB affixed to its distal end (Figure 1, Step D), allowing the MB to efficiently transfer electrons and generate an increased faradaic current.33, 35 Digestion releases the intact target DNA, which is now able to hybridize with a new, undigested ExTCT probe and catalyze a new cycle of probe transformation (Figure 1, Steps E through G). In this way, a single DNA target is able to trigger permanent transformation of multiple signaling probes from rigid stem-loop conformation to flexible linear structure and thereby generate an amplified faradaic current (Figure 1, Step H).

Figure 1.

Overview of the ExTCT sensor scheme. The ExTCT sensor consists of surface-bound, stem-loop DNA probes modified with a 5’ terminal phosphate, a 3’ terminal thiol group and an internal MB tag. In the absence of target, the relatively rigid stem-loop probe produces a small faradaic current (step A). In the presence of target DNA, a target-probe complex is formed that consists of a single-stranded region and a double-stranded duplex region (step B). Lambda exonuclease subsequently binds to the duplex and selectively hydrolyzes the phosphate-modified probe in the 5’-to-3’ direction (step C), effectively digesting the probe. Because the nuclease preferentially digests double-stranded DNA, the enzyme activity is halted as it reaches the single-stranded region. Digestion releases the intact target DNA, leaving behind a permanently “transformed” MB-labeled single-stranded probe (step D). The released target DNA can then hybridize and initiate digestion of another probe (steps E though G). As such, a single target DNA can trigger the transformation of multiple DNA probes, resulting in signal amplification (step H).

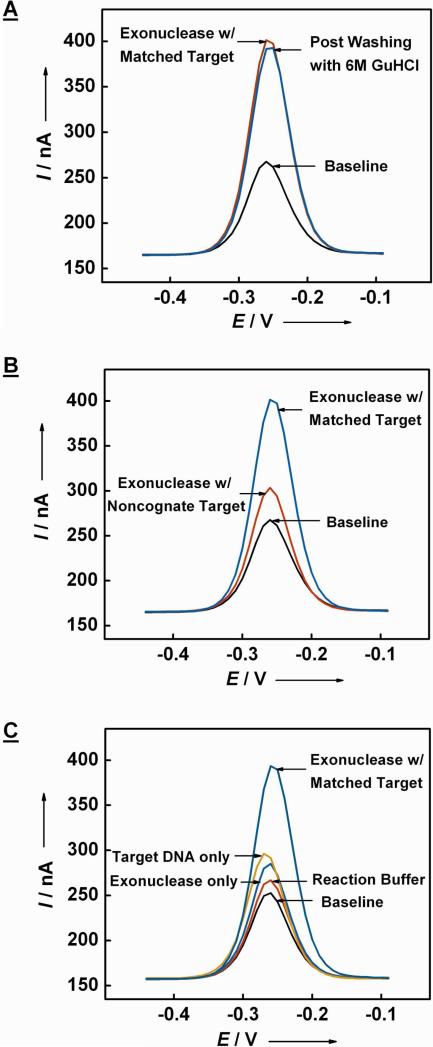

Upon challenging the ExTCT sensor with 200 nM perfectly-matched target (2) and 50 units of exonuclease, we obtained 170% signal gain (Figure 2A, with target). This signal gain persisted even after washing the sensor with 6.0 M guanidine hydrochloride (Figure 2A, post washing), confirming that the electrochemical signal is indeed the result of a permanent change in the structure of the signaling probe (1). Furthermore, when the transformed sensor was re-challenged with 200 nM target DNA (2), it showed negligible change in electrochemical signal, indicating that all immobilized hairpin probes became digested and the target DNA can no longer hybridize to the digested probes (data not shown). The ExTCT sensor is also sequence-specific; when challenged with 200 nM non-cognate 29-nt target (3), the resulting signal was 26% of the signal obtained with the perfectly-matched target (2) (Figure 2B). When we further investigated the specificity of our sensor with mismatched targets, we found that the ExTCT sensor was limited to the discrimination of five or more mismatches (data not shown) due to the thermodynamic characteristic that is inherent in the stem-loop structure, consistent with the previous work on hybridization-based electrochemical stem-loop DNA sensor.33, 34

Figure 2.

The ExTCT sensor selectively responds to its target DNA. (A) AC voltammograms reveal 180% signal gain in faradaic current after enzymatic amplification. This increased current persists after washing the sensor in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) solution, verifying that the probe's structural transformation is permanent. (B) When the ExTCT sensor is challenged with a non-cognate target and exonuclease, we observe only 26% of the signal obtained with the perfectly-matched target. (C) Compared to faradaic currents obtained with a perfectly-matched target and exonuclease, negative-control reactions with reaction buffer only, lambda exonuclease only or target DNA only yield significantly smaller signals (10%, 29% and 26% of the positive control, respectively).

In order to explore the limits of the signal amplification mechanism, we performed three control experiments (Figure 2C). First, we incubated the sensor in the reaction buffer alone, and observed ~10% of the faradaic current obtained from the positive control reaction with the target DNA and exonuclease. This background signal could not be regenerated with 6.0 M guanidine hydrochloride washing (data not shown), suggesting that it may result from the non-specific adsorption of bovine serum albumin in the reaction buffer onto the sensor surface. Second, we challenged the sensor with 200 nM target DNA in the absence of exonuclease, and observed a signal equivalent to ~29% of the positive control, which presumably originates from direct hybridization between the signaling probe and target. We estimate that the open hairpins constituted approximately 0.35 pmol/cm2 since the surface coverage of the total immobilized probes was ~1.2 pmol/cm2. Finally, when we challenged the sensor with exonuclease without the target, the observed signal was ~26% of the positive control (Figure 2C). The signal change observed in the third control experiment suggests that: due to the imperfect selectivity of the lambda exonuclease, undesired digestion of the native ExTCT probe occurs under the experimental conditions. This parasitic phenomenon was also confirmed by gel electrophoresis experiments (see supporting information Figure S1).

Effect of Probe Density on ExTCT Sensor Performance

The surface density of the ExTCT probes is an important parameter contributing to signal gain, and it can be controlled by varying the probe concentration during sensor fabrication.39, 44 In order to optimize the gain, we characterized the performance of sensors fabricated with various concentrations of signaling probe (1) under standard reaction conditions with 200 nM perfectly-matched target DNA (2). The observed probe density increased monotonically with increasing probe concentration, and optimal signal gain was obtained from sensors fabricated with 1 μM signaling probe, which translates to a packing density of ~1.2 pmol/cm2 (see supporting information, Figure S2). Above this concentration, no further increases in signal gain were observed, presumably because the probe is saturated on the surface.

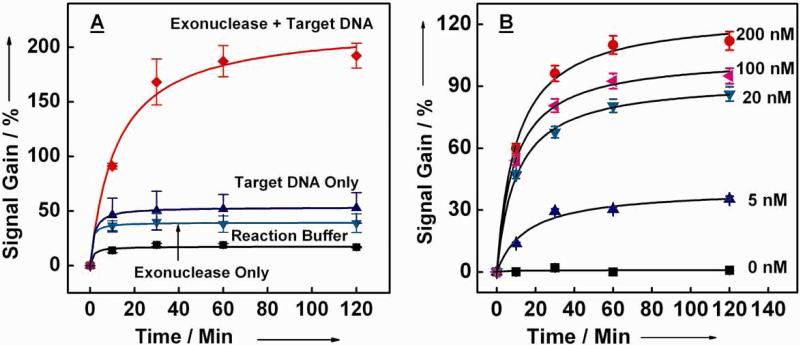

Efficiency of Target Recycling and Signal Amplification

Transformation of the surface-bound ExTCT probe in the presence of target DNA and exonuclease is relatively rapid, as illustrated by time-course experiments (Figure 3). Under standard reaction conditions with 200 nM target DNA (2), we observed signal gain saturation at ~160% within ~60 minutes. However, in the absence of exonuclease or target DNA, the sensor achieved saturation after 10 minutes at a much lower signal gain (Figure 3A). The observed delay in signal saturation in the presence of target suggests that multiple cycles of target hybridization, exonuclease digestion and probe transformation are indeed taking place during the reaction. Since direct DNA hybridization reaches saturation within ~ 10 minutes, we hypothesize that the exonuclease reaction is the rate-limiting step. Furthermore, differences in the reaction rates during the initial stage of the reactions are also evident. For example, during the first 10 min, the exonuclease–amplified enzymatic reaction yielded ~9% signal gain per minute. However, smaller rates of signal gain were observed with reactions containing target only (5% increase per minute) or exonuclease only (4.5% per minute) (Figure 3A). After the first ten minutes of digestion, the velocity of exonuclease/target-catalyzed probe transformation began to decelerate, presumably because the concentration of undigested, surface-bound probe had decreased. In Figure 3B, we collected time courses of the ExTCT sensor at different target concentrations (5 nM, 20 nM, 100 nM and 200 nM). We observe that the enzymatic reaction slowed down with decreasing target concentration. The reaction time required to reach 50% of the saturated signal increased from 8.20 to 8.76 and 12.3 min when the target concentration decreased from 100 to 20 and 5 nM, respectively (Figure 3B). Since the DNA hybridization step is relatively rapid,45 we estimated the rate constants of the enzymatic reaction by fitting the time course data to the Michaelis/Menten equation. We note that the background signal caused by nonspecific cleavage was subtracted from the total signal for this calculation (Figure 3B). Assuming a diffusion layer thickness of 5 μm,46 the calculated rate constants of lambda exonuclease for our ExTCT sensor were: the surface Michaelis-menten constant (Km) = 9.13 ± 2.7 nM, the apparent turn-over number of target DNA on the surface (kcat) = 0.030 s-1 and the efficiency (kcat/Km) of exonuclease = 3.29 × 106 M-1s-1. The apparent turn-over number of target DNA on the surface is ~100-fold lower than that observed in the solution reaction of the lambda exonuclease,43 suggesting that the efficiency of the enzyme is significantly hampered by the steric and electrostatic hindrance, as well as conformational restriction of the surface-tethered strands.

Figure 3.

Time-course experiments reveal the kinetic response of the ExTCT sensor to the perfectly-matched target and 50 units of exonuclease. (A) Sensors challenged with only target DNA (200 nM) or exonuclease reached saturation in approximately 10 minutes. In contrast, delayed signal saturation (~60 min) is observed when both target (200 nM) and exonuclease are present, presumably because multiple probes are being transformed by a single DNA target. (B) Time courses of the ExTCT sensor at different target concentration (5 nM, 20 nM, 100 nM and 200 nM).

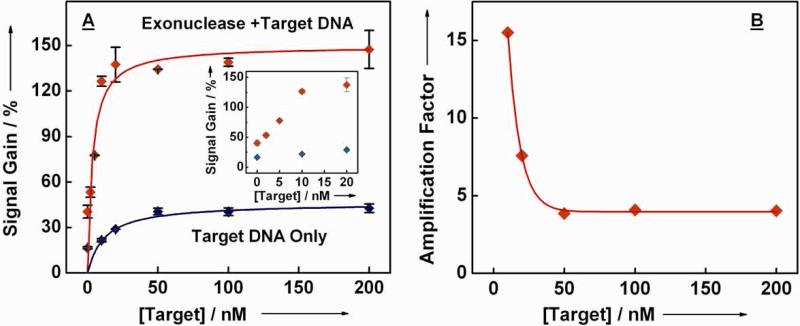

The ExTCT sensor responds sensitively and reproducibly to its target, as shown in the dose-response curve (Figure 4A). Without any background subtraction, the limit of detection (LOD) of the ExTCT sensor (~2 nM) marks a five-fold improvement over the hybridization-based sensor without the amplification mechanism (~10 nM). In an effort to quantitatively characterize the amplification effect of the ExTCT sensor, we define the amplification factor as the ratio of the net signal gain obtained with enzyme/target-catalyzed reaction to that obtained with target only after subtraction of background current; thus, a larger amplification factor is indicative of greater amplification and sensitivity. We observed that amplification factors of 16 and 8 were obtained at 10 nM and 20 nM target concentrations, respectively (Figure 4B). Of note, although amplification factor could not be calculated below 10 nM target concentrations, it is evident that even greater signal amplification factor could be attained. The amplification factor is limited to ~4 at high target concentrations (above 20 nM), presumably because of the enzyme-limited nature of the reaction.

Figure 4.

The ExTCT sensor responds sensitively and reproducibly to its target DNA. (A) Target DNA concentration calibration data (with and without exonuclease) show that the addition of lambda exonuclease greatly improves the limit of detection. Insert shows the calibration curve at low target concentrations. (B) The signal amplification factor, defined as the ratio of the net signal gain obtained with enzyme/target-catalyzed reaction to that obtained with target only after subtraction of background current, is ~16 at low target concentrations (< 10 nM) but decreases to ~4 at high target concentrations (> 20 nM).

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated a single step, single-reagent, isothermal, label-free DNA sensor architecture that utilizes a target recycling mechanism to achieve amplified electrochemical signals. In this assay, a single target DNA interacts with multiple probes to permanently transform their structure, yielding a large increase in signal amplitude. Interestingly, this mechanism operates more efficiently at low target concentrations (< 10 nM) where we observe over 16-fold signal amplification. The sensitivity of the current probe design cannot achieve sufficient sensitivity for direct detection of genomic DNA derived by phenol:chloroform extraction from physiological samples (typically ~30 ng/μl).47 However, we have identified a number of limiting factors that can be optimized to improve the performance. For example, the sensitivity of our sensor is primarily limited by the stability of the employed probe, exhaustion of available probes on the surface and limited selectivity of the lambda exonuclease, which produces background signal through non-specific digestion of probes even at single-stranded segments.41-43 However, with further optimization of the probe structure to incorporate different types of modified nucleotides—for example, peptide nucleic acids (PNA) or locked nucleic acids (LNA)—and through the use of more selective exonucleases or utilizing solution-based, rather than surface-based reaction, we believe the ExTCT architecture could offer an interesting alternative approach for convenient electrochemical DNA detection at the point of care.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for the article: “Electrochemical DNA Detection via Exonuclease and Target-Catalyzed Transformation of Surface-Bound Probe” by Kuangwen Hsieh, Yi Xiao* and H. Tom Soh*

Probe Density Optimization. Signal gain for the ExTCT sensor was optimized by controlling the concentration of signaling probe (1) during sensor fabrication. Sensors fabricated with various concentrations of probe (1) were challenged with 200 nM 29-base perfectly-matched target (2) and 50 units of lambda exonuclease in 1× lambda exonuclease reaction buffer with 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 1 h. We found that the signal gains we obtained reached a plateau of ~160% with sensors fabricated with 1 μM probe (1) or more (Supplementary Figure S3). The signaling probe packing density was calculated using Eqn. 1 [1], in which Iavg(Eo) is the average ac peak current in the voltammogram, n is the number of electrons transferred per redox event, F is the Faraday constant, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature, and Eac is the peak amplitude, and f is the frequency of the applied ac voltage perturbation.

| Eqn. 1 |

The electrode area was measured from the reduction peak area during electrode cleaning in 0.05 M H2SO4 solution. Experimental results demonstrated that the optimal probe packing density was ~1.2 pmol cm-2, as achieved when 1 μM signaling probe was used for preparation. Based on these findings, we used 1 μM signaling probe to fabricate all of our ExTCT sensors in this work.

Exonuclease and Target-Catalyzed Transformation of Probe in Solution. To visualize probe transformation and enzymatic amplification, we performed exonuclease and target-catalyzed probe transformation in solution and analyzed the resulting products by gel electrophoresis. We tested 400 nM target DNA, 1.6 μM probe DNA, or a combination of the two in reaction buffer with or without 50 units of lambda exonuclease. The total reaction volume was 25 μL. The reaction was carried out in a benchtop thermocycler (Eppendorf Master Gradient) at 37 °C for 90 minutes. After the reaction, 10 μL of reaction product were loaded onto a 4.5% low melting-point 1× TAE agarose gel with 1.5× GelStar dye, and then run in 1× TAE buffer at 80 V for 50 minutes. Gel imaging revealed that lambda exonuclease minimally digests single-stranded nonphosphorylated target DNA (Figure S2, lanes 2 and 3), and partially digests phosphate-modified probes (lanes 4 and 5). When target and four-fold excess probe are combined, duplexes are observed in addition to excess un-hybridized probe (lane 6). Addition of lambda exonuclease to this mixture enables probe transformation (lane 7). At the end of the reaction, a faint band of target-probe duplex is still observed, but the probe band has disappeared, indicating that most of the original probe was transformed. The bright, fast-migrating band on the gel represents both released DNA targets and transformed linear probes.

Reference:

(1) Sumner, J. J.; Weber, K. S.; Hockett, L. A.; Creager, S. E. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 7449-7454.

Figure S1. Gel image of reaction products of enzymatic digestion and probe transformation. Lanes 1 and 8 are 20-base double-stranded ladder. From the gel, we observe minor digestion of single-stranded nonphosphorylated target DNA (lanes 2 and 3), and some digestion of phosphate-modified probes (lanes 4 and 5). When target and four-fold excess probe are mixed, target-probe duplexes are observed in addition to excess probe (lane 6). Addition of lambda exonuclease to the target/probe mixture enables both enzymatic digestion and probe transformation, yielding a bright, fast-moving band comprising released DNA targets and linear, transformed probes (lane 7). A faint band of target-probe duplex can still be observed after the reaction is complete.

Figure S2. Optimization of probe packing density on the electrode. Sensors fabricated with 1 μM probe (a converging probe packing density of ~1.2 pmol cm-2) or more during fabrication produced optimal signal gains in enzyme-amplified reaction. (A) The dependence of probe concentrations on signal gain. (B) The relation of probe density to signal gain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Office of Naval Research, National Institutes of Health, and the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies through the U.S. Army Research Office. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Xinhui Lou for inspiring conversations. The authors are especially grateful to Dr. Ryan White, Kareem Ahmad, Dr. Andrew Csordas, Kory Plakos, Scott Ferguson, Steven Buchsbaum, Jonathan Adams and Seung Soo Oh for their assistance and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Umek RM, Lin SW, Vielmetter J, Terbrueggen RH, Irvine B, Yu CJ, Kayyem JF, Yowanto H, Blackburn GF, Farkas DH, Chen YP. J. Mol. Diagn. 2001;3:74–84. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao JC, Mastali M, Gau V, Suchard MA, Moller AK, Bruckner DA, Babbitt JT, Li Y, Gornbein J, Landaw EM, McCabe ERB, Churchill BM, Haake DA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:561–570. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.561-570.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JG, Cheong KH, Huh N, Kim S, Choi JW, Ko C. Lab Chip. 2006;6:886–895. doi: 10.1039/b515876a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeung SW, Lee TMH, Cai H, Hsing IM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palchetti I, Mascini M. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;391:455–471. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1876-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csordas AI, Delwiche MJ, Barak JD. Sens. Actuators, B. 2008;134:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey L, Mitnik L. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:1386–1397. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200205)23:10<1386::AID-ELPS1386>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Rivas G, Cai X, Palecek E, Nielsen P, Shiraishi H, Dontha N, Luo D, Parrado C, Chicharro M, Farias PAM, Valera FS, Grant DH, Ozsoz M, Flair MN. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1997;347:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardeniers JGE, van den Berg A. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004;378:1700–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Mozaz S, de Alda MJL, Barcelo D. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006;386:1025–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palchetti I, Mascini M. Analyst. 2008;133:846–854. doi: 10.1039/b802920m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf N, Goritz M, Kramer R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4013–4015. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossmann TN, Roglin L, Seitz O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7119–7122. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saghatelian A, Guckian KM, Thayer DA, Ghadiri MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:344–345. doi: 10.1021/ja027885u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Polsky R, Xu DK. Langmuir. 2001;17:5739–5741. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SJ, Taton TA, Mirkin CA. Science. 2002;295:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1067003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Science. 2000;289:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam JM, Stoeva SI, Mirkin CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5932–5933. doi: 10.1021/ja049384+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caruana DJ, Heller A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:769–774. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu G, Wan Y, Gau V, Zhang J, Wang LH, Song SP, Fan CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6820–6825. doi: 10.1021/ja800554t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei F, Wang JH, Liao W, Zimmermann BG, Wong DT, Ho CM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patolsky F, Weizmann Y, Willner I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:770–772. doi: 10.1021/ja0119752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao Y, Pavlov V, Niazov T, Dishon A, Kotler M, Willner I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7430–7431. doi: 10.1021/ja031875r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duck P, Alvarado-Urbina G, Burdick B, Collier B. Biotechniques. 1990;9:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekkaoui F, Poisson I, Crosby W, Cloney L, Duck P. Biotechniques. 1996;20:240–248. doi: 10.2144/96202rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodrich TT, Lee HJ, Corn RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4086–4087. doi: 10.1021/ja039823p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodrich TT, Lee HJ, Corn RM. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:6173–6178. doi: 10.1021/ac0490898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HJ, Li Y, Wark AW, Corn RM. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:5096–5100. doi: 10.1021/ac050815w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiesling T, Cox K, Davidson EA, Dretchen K, Grater G, Hibbard S, Lasken RS, Leshin J, Skowronski E, Danielsen M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li JJ, Chu Y, Lee BY-H, Xie XS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sando S, Sasaki T, Kanatani K, Aoyama Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15720–15721. doi: 10.1021/ja0386492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sando S, Narita A, Sasaki T, Aoyama Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:1002–1007. doi: 10.1039/b418078j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan CH, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:9134–9137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lubin AA, Lai RY, Baker BR, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5671–5677. doi: 10.1021/ac0601819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ricci F, Lai RY, Plaxco KW. Chem. Commun. 2007:3768–3770. doi: 10.1039/b708882e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Y, Qu XG, Plaxco KW, Heeger A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11896–11897. doi: 10.1021/ja074218y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gooding JJ. Electroanaylsis. 2002;14:1149–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2002;469:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao Y, Lai RY, Plaxco KW. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2875–2880. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly SO, Barton JK. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997;8:31–37. doi: 10.1021/bc960070o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sriprakash KS, Lundh N, Mooonhuh M, Radding CM. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:5438–5445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Little JW. Gene Amplif. Anal. 1981;2:135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitsis PG, Kwagh JG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3057–3063. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ricci F, Lai RY, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW, Sumner JJ. Langmuir. 2007:6827–6834. doi: 10.1021/la700328r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao Y, Wolf LK, Georgiadis RM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3370–3377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karlsson R, Roos H, Fagerstam L, Persson B. Methods. 1994;6:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pilcher KE, Pascale G, Fey P, Kowal AS, Chisholm RL. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1329–1332. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information for the article: “Electrochemical DNA Detection via Exonuclease and Target-Catalyzed Transformation of Surface-Bound Probe” by Kuangwen Hsieh, Yi Xiao* and H. Tom Soh*

Probe Density Optimization. Signal gain for the ExTCT sensor was optimized by controlling the concentration of signaling probe (1) during sensor fabrication. Sensors fabricated with various concentrations of probe (1) were challenged with 200 nM 29-base perfectly-matched target (2) and 50 units of lambda exonuclease in 1× lambda exonuclease reaction buffer with 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 1 h. We found that the signal gains we obtained reached a plateau of ~160% with sensors fabricated with 1 μM probe (1) or more (Supplementary Figure S3). The signaling probe packing density was calculated using Eqn. 1 [1], in which Iavg(Eo) is the average ac peak current in the voltammogram, n is the number of electrons transferred per redox event, F is the Faraday constant, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature, and Eac is the peak amplitude, and f is the frequency of the applied ac voltage perturbation.

| Eqn. 1 |

The electrode area was measured from the reduction peak area during electrode cleaning in 0.05 M H2SO4 solution. Experimental results demonstrated that the optimal probe packing density was ~1.2 pmol cm-2, as achieved when 1 μM signaling probe was used for preparation. Based on these findings, we used 1 μM signaling probe to fabricate all of our ExTCT sensors in this work.

Exonuclease and Target-Catalyzed Transformation of Probe in Solution. To visualize probe transformation and enzymatic amplification, we performed exonuclease and target-catalyzed probe transformation in solution and analyzed the resulting products by gel electrophoresis. We tested 400 nM target DNA, 1.6 μM probe DNA, or a combination of the two in reaction buffer with or without 50 units of lambda exonuclease. The total reaction volume was 25 μL. The reaction was carried out in a benchtop thermocycler (Eppendorf Master Gradient) at 37 °C for 90 minutes. After the reaction, 10 μL of reaction product were loaded onto a 4.5% low melting-point 1× TAE agarose gel with 1.5× GelStar dye, and then run in 1× TAE buffer at 80 V for 50 minutes. Gel imaging revealed that lambda exonuclease minimally digests single-stranded nonphosphorylated target DNA (Figure S2, lanes 2 and 3), and partially digests phosphate-modified probes (lanes 4 and 5). When target and four-fold excess probe are combined, duplexes are observed in addition to excess un-hybridized probe (lane 6). Addition of lambda exonuclease to this mixture enables probe transformation (lane 7). At the end of the reaction, a faint band of target-probe duplex is still observed, but the probe band has disappeared, indicating that most of the original probe was transformed. The bright, fast-migrating band on the gel represents both released DNA targets and transformed linear probes.

Reference:

(1) Sumner, J. J.; Weber, K. S.; Hockett, L. A.; Creager, S. E. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 7449-7454.

Figure S1. Gel image of reaction products of enzymatic digestion and probe transformation. Lanes 1 and 8 are 20-base double-stranded ladder. From the gel, we observe minor digestion of single-stranded nonphosphorylated target DNA (lanes 2 and 3), and some digestion of phosphate-modified probes (lanes 4 and 5). When target and four-fold excess probe are mixed, target-probe duplexes are observed in addition to excess probe (lane 6). Addition of lambda exonuclease to the target/probe mixture enables both enzymatic digestion and probe transformation, yielding a bright, fast-moving band comprising released DNA targets and linear, transformed probes (lane 7). A faint band of target-probe duplex can still be observed after the reaction is complete.

Figure S2. Optimization of probe packing density on the electrode. Sensors fabricated with 1 μM probe (a converging probe packing density of ~1.2 pmol cm-2) or more during fabrication produced optimal signal gains in enzyme-amplified reaction. (A) The dependence of probe concentrations on signal gain. (B) The relation of probe density to signal gain.