Abstract

Background

In the U.S., prostate cancer incidence is higher among Black than white males, with a higher proportion of Blacks diagnosed with advanced stage cancer.

Methods

Prostate cancer incidence (1999–2001) and census tract data were obtained for 66,468 cases in four states that account for 20% of U.S. Blacks: Georgia, Florida, Alabama and Tennessee. Spatial clusters of localized-stage prostate cancer incidence were detected by spatial scan. Clusters were examined by relative risk, population density, socioeconomic and racial attributes.

Results

Overall prostate cancer incidence rates were higher in Black than white men and a lower proportion of Black cases were diagnosed with localized-stage cancer. Strong associations were seen between urban residence and high relative risk of localized-stage cancer. Highest relative risks generally occurred in clusters with lower percent Black population than the national average. Conversely, of eight non-urban clusters with significantly elevated relative risk of localized-disease, seven had a higher proportion of Blacks than the national average. Furthermore, positive correlations between percent Black population and relative risk of localized-stage cancer were seen in Alabama and Georgia.

Conclusion

Association between urban residence and high relative risk of localized-stage disease (favorable prognosis) persisted after spatial clusters were stratified by percent Black population. Unexpectedly, seven of eight non-urban clusters with high relative risk of localized-stage disease had a higher percentage of Blacks than the U.S. population.

Impact

Although evidence of racial disparity in prostate cancer was found, there were some encouraging findings. Studies of community-level factors that might contribute to these findings are recommended.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, spatial statistics, race

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer and second leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States. Despite declines in prostate cancer incidence and mortality since the early 1990s, Black men continue to be disproportionately affected by prostate cancer. Between 1997 and 2001, prostate cancer incidence rates were approximately 60% higher in Black men compared to white men (1, 2). Black men also have the highest death rate from prostate cancer of any racial group in the United States, with recent data indicating that the death rate for Black men is 2.4 times higher than for white men (1).

Clinical disease characteristics, including stage at diagnosis and tumor grade, are key predictors of survival following a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Between 1999 and 2005, the 5-year relative survival rate for both white and Black men diagnosed with local or regional stage prostate cancer approached 100%. When diagnosed with distant stage disease, 5-year survival decreased to 30.6% for white and 28.5% for Black men (3). Recent population-based epidemiologic studies indicate that Black men are approximately twice as likely as white men to be diagnosed with advanced stage prostate cancer (4) and men of low socioeconomic status are more likely than men of higher socioeconomic status to be diagnosed with advanced-stage prostate cancer (4–6).

The mechanisms by which racial category influences the stage at which a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer are unclear. Hypotheses relate to location-specific factors such as access to and utilization of healthcare including screening services (4) and area-level characteristics including poverty, education level, and population density along the urban-rural continuum; 7–9). Within the United States, age-adjusted prostate cancer incidence rates vary at the local, state, and regional level, and are generally highest in the upper Midwest and southeastern states (10). In a study of localized-stage prostate cancer in Maryland, Kentucky, Georgia, and Florida (11), compared to white men, Black men had lower odds of being diagnosed with localized-stage disease in each state, reaching statistical significance in the largest state, Florida. In another recent study of spatial trends in prostate cancer incidence in the United States, large clusters of counties were found within the southeastern United States where prostate cancer incidence was lower than expected (12). These findings warrant further investigation of the spatial clustering of prostate cancer in the southeast. To our knowledge, no published study has evaluated spatial clustering of prostate cancer incidence by race and stage at diagnosis within this region.

The objective of the current study was to utilize prostate cancer incidence data obtained from state cancer registries to identify stage of diagnosis- and race- specific spatial clustering of prostate cancer incidence among men living in the four southeastern states of Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Tennessee, which accounted for 20% of the United States Black population in the year 2000 (13). We hypothesized that proportions of white and Black men would differ between spatial clusters with statistically high versus low risk ratios of localized-stage prostate cancer.

Methods

Data Set Development

The census tract of residence was reported for incident prostate cancer cases over varying years from state cancer registries in four southeastern states: Tennessee (1989–2001), Alabama (1996–2002), Georgia (1999–2002), and Florida (1996–2003). Census tracts varied in size, with urban and suburban tracts typically covering smaller geographic areas than rural tracts, reflecting their higher population density. Case reports were restricted to non-Hispanic white and Black men, respectively. Individual level data available for cases included race, age and stage at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, and year 2000 census tract of residence (14). The multistate dataset included all cases diagnosed during the three years from 1999 to 2001, bracketing the 2000 U.S. population census. Five cases were excluded from analyses because of missing census tracts of residence (four from Georgia and one from Florida) yielding 66,468 cases. A total of 51,093 cases (76.9%) with localized-stage disease were included in spatial analyses. Analyses of the remaining 15,375 cases (23.1%) with regional and distant stage disease (10.7%) or missing stage disease (12.4%) respectively were less informative. Because the analytic dataset provided a robust sample for analysis, the focus of this report is the spatial clustering and demographic attributes of men who were diagnosed with localized stage prostate cancer.

Cluster Identification

A Poisson-model based spatial scan statistic (SatScan, ™ SaTScan.org, Boston, MA; 15) was used to detect spatial clusters within the four-state study area. Analyses of each state were also performed to find patterns that could be masked in the overall analysis. All clusters detected were age-adjusted to the U.S. standard 2000 population, according to its age distribution (18 age groups: 0–4, 5–9, …, 80–84, and 85+).

The spatial statistic used windows of variable shape and size to scan across a geographical region. Each shape, size and location defined a candidate cluster of census tracts. Statistically significant clusters were defined by a p-value < 0.05 based on the Monte Carlo method. The spatial scan statistic adjusted for age. It also adjusted for the multiple testing inherent when large numbers of candidate cluster areas are considered. (15) Thus, type I error was well controlled. Both circular and elliptic windows can be used to search for possible clusters. The elliptical window used in this report has been shown to provide favorable power and sensitivity compared with other window shapes when the maximum window is not too large (16). The elliptical window is also a reasonable shape since spatial clusters can take many forms. The scan window searched for ellipses of varying sizes and angles defined by the ratio of their long to short axes to obtain representative ellipse shapes. Axis ratios of 1.5, 2, 3, and 4 were selected for this analysis. Ellipse orientations around centroids were chosen based on prior specifications (16). The allowable numbers of equal-sized angles in a 360-degree rotation were set at 4, 6, 9, and 12 for ellipse axis ratios of 1.5, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. To choose an optimal search window size, a 50% maximum search window of the total population was initially used followed by smaller search windows (e.g., 25%, 5%, and 0.5%). Large clusters were often found to include demographically diverse census tracts. The 0.5% maximum window size provided added resolution in suburban areas without loss of detail in urban centers. Because some census tracts accounted for 0.3% of state population, smaller window sizes could not be used.

Demographic characterization of clusters

Census tract-level socioeconomic data were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau for the year 2000 (17). Socioeconomic status (SES) was estimated by cluster with values of SES variables for tracts within clusters, weighted by each tract’s population. Variables used in analyses included percent of adults without a high school diploma, percent of adults with bachelor degrees, percent of families living below poverty level, percent of people living below poverty level, median household income in dollars, percent unemployment, and percent Black population. The rural urban continuum score was based on county-level data. The most urban counties were assigned a score of 1 and the most rural counties given a score of 9. Cluster population density was estimated with the weighted index of the tracts in the cluster (18). A three level categorical variable was used to define population density. Urban clusters were defined as clusters having a weighted urban-rural index of 2 or less, indicating a population density corresponding with a metropolitan county of at least 250,000 people. Suburban clusters had rural-urban continuum index values greater than two and less than six (i.e., density ranging from a metropolitan county with less than 250,000 people to a county with an urban population of at least 2,500 located adjacent to a metropolitan area. Clusters with population density corresponding to a county with fewer than 20,000 urban residents that was not adjacent to metropolitan areas were classified as rural.

Summary statistics

The Fisher’s exact test statistic was used to examine associations between relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer and population density in the 97 spatial clusters from the multistate analyses, with further analyses of clusters stratified by percent Black population based on a cut point of 12.3%, the percent “Black only” population estimated from the 2000 U.S. census. (13) For clusters with statistically significant relative risks of localized-stage prostate cancer, Pearson’s correlations were performed to examine associations between relative risk and demographic variables (P<0.05, t-test, correlation coefficient significantly different from zero; 19). Correlations were examined by state and for all four states combined.

Results

Incidence

Among Black and white men in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, from 1999 to 2001 a total of 51,093 of 66468 (76.9%) reported incident cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed at localized-stage (Table 1). Overall incidence rates of prostate cancer were more than 50% higher in Black than white males, with a higher proportion of white than Black cases diagnosed with localized-stage disease in each of the four states and during each diagnosis year (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Incident cases of prostate cancer by stage, race, state and year with overall age-adjusted incidence rates-- Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, 1999 to 2001

| Black | White | Both races | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | Late/Missing | All Cases | Localized | Late/Missing | All Cases | All Cases | ||||||||

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | Incidence† | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | Incidence† | No. | Incidence† | |

| State | ||||||||||||||

| Alabama | 1343 | 80% | 326 | 20% | 1669 | 158.27 | 4006 | 85% | 688 | 15% | 4694 | 97.36 | 6363 | 108.47 |

| Florida | 3164 | 71% | 1290 | 29% | 4454 | 239.07 | 27958 | 75% | 9375 | 25% | 37333 | 147.51 | 41787 | 154.21 |

| Georgia | 2736 | 75% | 898 | 25% | 3634 | 221.49 | 7325 | 82% | 1570 | 18% | 8895 | 130.73 | 12529 | 148.3 |

| Tennessee | 608 | 71% | 253 | 29% | 861 | 117.84 | 3953 | 80% | 975 | 20% | 4928 | 74.38 | 5789 | 78.8 |

| Diagnosis Year | ||||||||||||||

| 1999 | 2442 | 72% | 931 | 28% | 3373 | 191.61 | 14417 | 77% | 4374 | 23% | 18791 | 129.67 | 22164 | 136.76 |

| 2000 | 2662 | 73% | 960 | 27% | 3622 | 204.69 | 14777 | 77% | 4417 | 23% | 19194 | 132.88 | 22816 | 141.11 |

| 2001 | 2747 | 76% | 876 | 24% | 3623 | 204.28 | 14048 | 79% | 3817 | 21% | 17865 | 123.69 | 21488 | 132.88 |

| Total | 7851 | 74% | 2767 | 26% | 10618 | 200.19 | 43242 | 77% | 12608 | 23% | 55850 | 128.74 | 66468 | 136.9 |

Age-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000

Spatial clusters of census tracts

When cases in all four states were examined with the spatial scan method, 97 clusters of census tracts were found with statistically significant relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer incidence (Figure 1). Four of these clusters contained only one census tract and 26 contained less than 10 census tracts. The median number of census tracts per cluster was 28 and the maximum number of census tracts was 75. More clusters with higher relative risks were detected in Florida and Georgia than in Alabama or Tennessee, suggesting that there was interstate variation in localized-stage prostate cancer incidence.

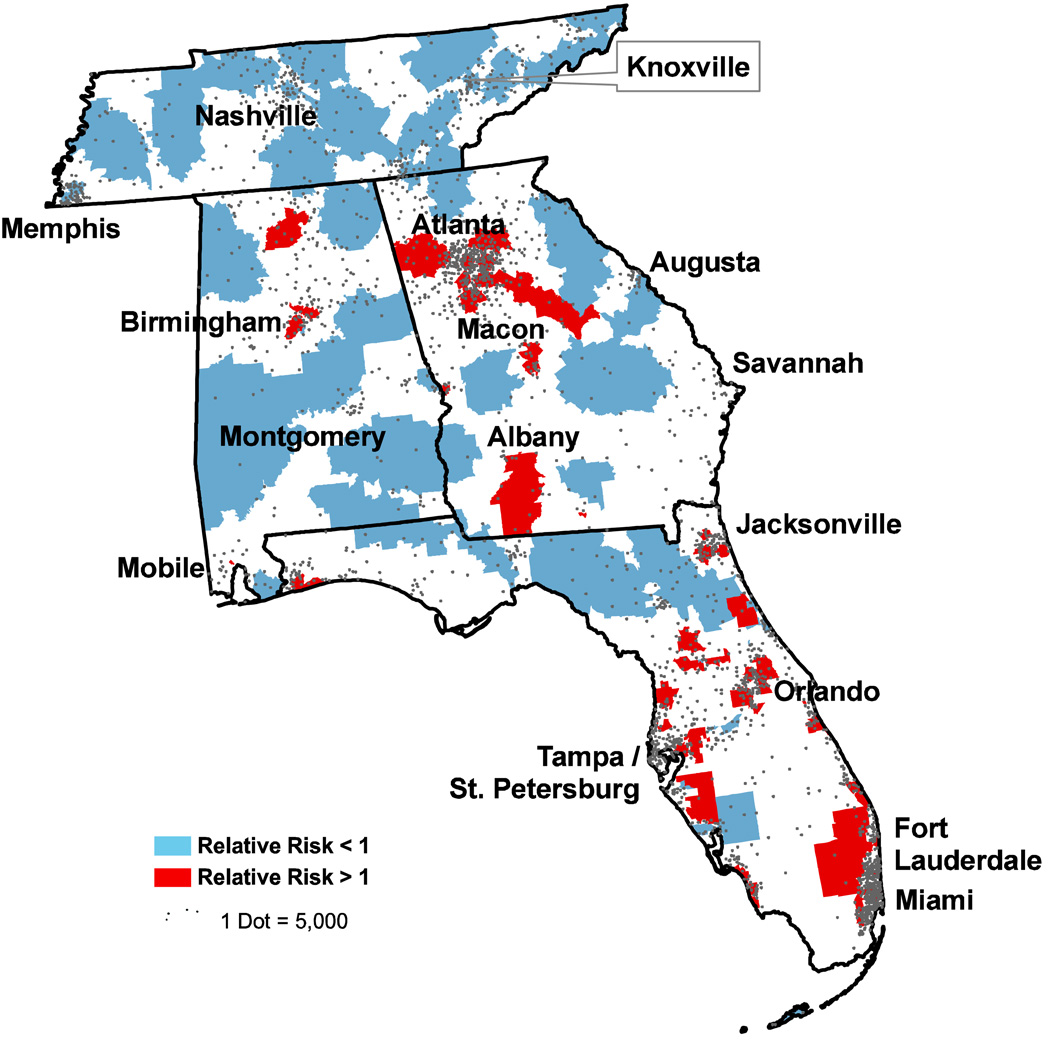

Figure 1.

Multistate analysis of spatial clusters with statistically significant relative risks of localized-stage prostate cancer compared to the background incidence rate - Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida: 1999 to 2001*

* Cases restricted to Black and white males only

There were strong associations between urban density and high relative risk of prostate diagnosis at localized-stage (Table 2). The associations persisted after clusters were stratified at a cut point of >12.3% percent “Black only” population (national average, 2000 U.S. Census). Among urban clusters with a lower percent of Black residents than the national average, the highest relative risk values ranged from 8.2 to 3.5 (Table 3). These clusters were all located in Florida. The highest relative risk values for urban clusters with higher percentages of Black residents were lower, ranging from 2.3 to 2.0. Furthermore, these clusters were dispersed across Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. Of the 49 clusters with higher relative risks of localized-stage prostate cancer, only eight were non-urban clusters, all of which occurred in suburban areas. Seven of the eight clusters had higher proportions of Black population than the national average (Table 1) and six had relatively favorable SES (i.e., education and income levels; Table 2). Compared with the overall analysis, general patterns of spatial clusters across the four-state study area persisted in analyses restricted to whites, with loss of detail in analyses restricted to Blacks owing to small numbers of cases (data not shown). However, spatial patterns in race-specific maps were consistent with the overall pattern: high urban and low rural relative risks of localized-stage prostate cancer.

Table 2.

Clusters of localized-stage prostate cancer and associations between relative risk and population density, with stratification by percent-Black population* – Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee, 1999 to 2001

| Relative Risk, early-stage prostate cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Population Density | No. Clusters | > 1.0 | < 1.0 | P-value† |

| All Census Tract Clusters | ||||

| County population ≥ 250,000 | 53 | 41 | 12 | <0.0001 |

| County population < 250,000 | 44 | 8 | 36 | |

| Clusters with > 12.3% black population* | ||||

| County population ≥ 250,000 | 23 | 18 | 5 | 0.0005 |

| County population < 250,000 | 25 | 7 | 18 | |

| Clusters with ≤ 12.3% black population* | ||||

| County population ≥ 250,000 | 30 | 23 | 7 | <0.0001 |

| County population < 250,000 | 19 | 1 | 18 | |

| Total No. Clusters | 97 | 49 | 48 | |

12.3% of the United States population reported race as “Black only” in the 2000 Census

Fisher’s Exact Test

Table 3.

Top five urban spatial clusters with the highest risk ratios of localized-stage prostate cancer and all non-urban clusters with risk ratios greater than 1.0, by percent-Black population

| Percent Black Population in Cluster | Population Density |

Relative Risk |

Cluster Location |

No. Tracts in Cluster |

>16.5% Adults College Degrees |

Median household income>$36,500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than U.S. (12.3%) | Urban | 8.2 | West Central FL | 1 | No | No |

| 4.8 | Central FL | 2 | No | No | ||

| 3.8 | Metro Miami FL | 8 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 3.7 | Southwest FL | 2 | No | Yes | ||

| 3.5 | East Central FL | 1 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Suburban | 1.5 | Northwest GA | 37 | Yes | Yes | |

| Greater than U.S. (12.3%) | Urban | 2.3 | Southeast FL | 10 | No | No |

| 2.1 | Metro Atlanta GA | 49 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2.1 | Southwest AL | 12 | No | No | ||

| 2.1 | North Central FL | 28 | No | Yes | ||

| 2.0 | Metro Atlanta GA | 61 | Yes | No | ||

| Suburban | 5.4 | North Central FL | 2 | No | No | |

| 2.6 | South Central GA | 7 | Yes | No | ||

| 2.3 | Northeast FL | 2 | No | Yes | ||

| 1.9 | Northern AL | 27 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1.7 | Southwest GA | 54 | No | No | ||

| 1.6 | Central GA | 51 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1.5 | East of Atlanta | 27 | Yes | Yes | ||

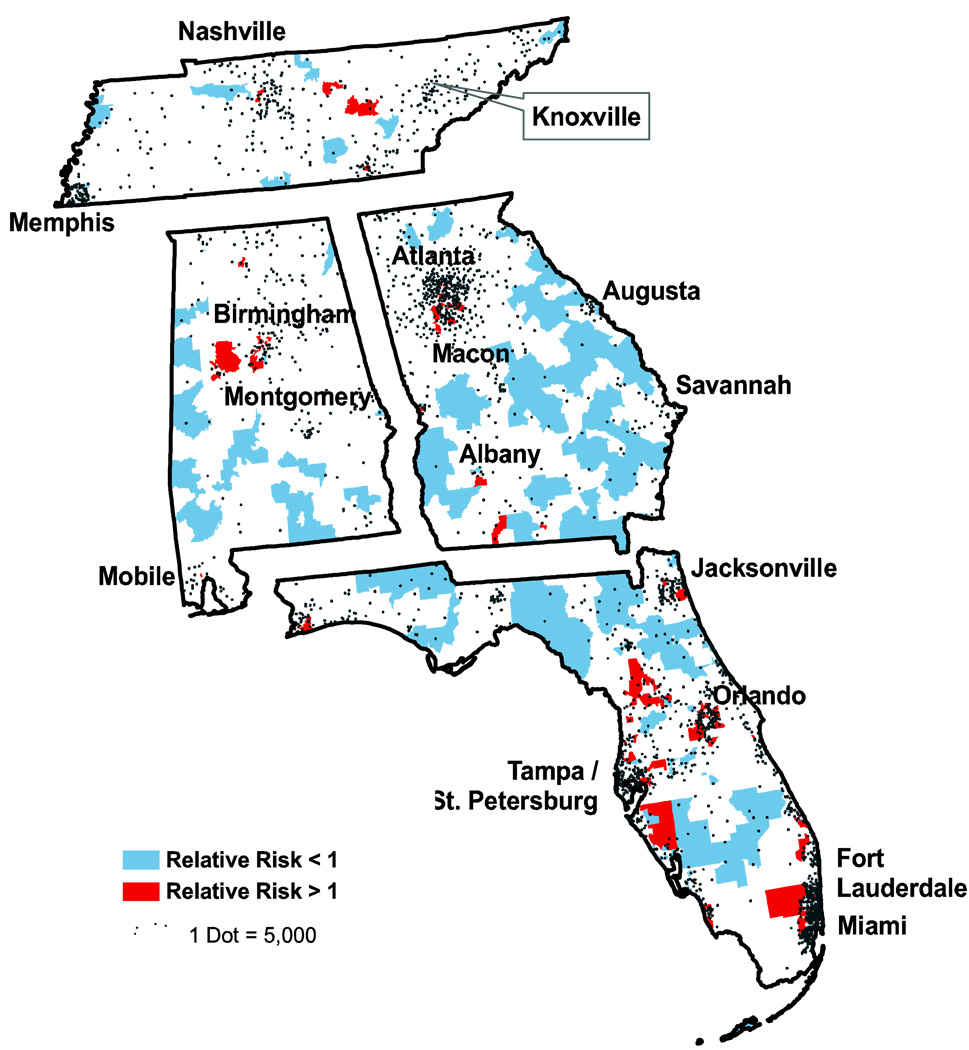

When clusters in individual states were examined separately (Figure 2), the spatial patterns of clusters in Florida and Alabama resembled those in the analysis of all four states combined (Figure 1). In Northwest Georgia however, near the Alabama border, a cluster of high relative risk of localized-stage disease was not observed in the Georgia-only analysis, and two clusters of high relative risk of localized-stage cancer were seen in east-central Tennessee. Furthermore, the number and size of clusters with low relative risk in Tennessee decreased.

In correlations between census tract-level socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer, low population density was inversely correlated with high relative risk of localized-stage disease (Table 4). This correlation was observed in both the four-state study area and the individual states: Alabama (−0.71), Florida (−0.36), Georgia (−0.67), and Tennessee (−0.35), although it was not statistically significant in the latter state. The correlation between the percent Black population within clusters and relative risk for localized-stage disease was close to 0 in the multistate analysis; however, statistically significant positive correlations between the percent Black population and the relative risk were found in Alabama and Georgia, and a non-significant positive correlation was found in Tennessee. A correlation was seen between census tract-level measures of household income and relative risk of localized-stage disease, which was statistically significant in analyses restricted to Florida and Georgia. In Georgia a significant correlation was observed between tract-level measures of college graduation rates and relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients between relative risk and demographic attributes for statistically significant spatial clusters of localized stage prostate cancer*

| Area | AL | FL | GA | TN | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Clusters | 26 | 72 | 38 | 13 | 97 |

| Rurality | −0.63* | −0.30* | −0.57* | −0.25 | −0.42* |

| Black population (%) | 0.41* | 0.01 | 0.62* | 0.34 | 0.04 |

| Household Income | 0.17 | 0.32* | 0.33* | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| Adults with no high school diploma (%) | −0.22 | −0.09 | −0.4* | −0.48 | −0.13 |

| Adult college graduates (%) | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.48* | 0.61 | 0.09 |

| Family poverty (%) | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.22 | −0.09 |

| Poverty (%) | 0.09 | −0.1 | −0.05 | −0.17 | −0.11 |

| Unemployment (%) | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.26 | −0.06 | −0.07 |

T-test, correlation coefficient differs from zero, P<0.05

Conclusion

As expected based on previous studies illustrating social disparities related to prostate cancer, this study found higher incidence rates of prostate cancer among Black compared to white males with a lower proportion of cases diagnosed at the localized-stage among Black men. Furthermore, the absolute values of high relative risks of localized-stage prostate cancer were highest in urban clusters with relatively low percent Black population. Despite these findings, the present study also revealed encouraging evidence that could facilitate progress in reducing these previously described racial disparities in prostate cancer incidence and mortality. In Georgia and Alabama, for example, localized-stage prostate cancer was positively correlated with Black racial category. The correlation between localized-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis and percent Black population could be interrelated with several factors including but not limited to income, education, urban residence, or health promotion efforts. Studies are recommended of community-level factors that may have contributed to the positive correlations between Black race and early stage prostate cancer in these two states. In addition several clusters with high relative risks and greater than the median Black population were found outside major metropolitan areas. Most of these clusters had relatively high proportions of people with college degrees or favorable income levels. Results in the four-state and individual-state analyses suggest that state-level interventions may be having differential effects in the individual states. Future studies should focus on evaluating small area-level characteristics, including health education campaigns and access to healthcare facilities within clusters with more favorable prognosis that are located outside major metropolitan areas.

Prostate cancer clusters with high relative risk of localized-stage disease tended to occur in urban areas, while clusters with low relative risk of localized-stage disease tended to occur in less urban areas. These associations, which persisted after stratifying clusters by percent-Black population, may reflect other evidence of urban versus rural differences in access to prostate cancer screening. This finding may provide context for other studies of prostate cancer incidence and mortality. In one study of prostate cancer incidence and mortality data in Illinois, age-adjusted prostate cancer incidence significantly decreased with decreasing population density (20). Similarly, urban residence was positively associated with prostate cancer incidence in another recent study (21). The results of those studies may reflect an increased likelihood of being screened for prostate cancer in an urban area compared to a rural one, owing to increased availability of medical services. This increased surveillance also may explain our finding of higher relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer in urban than non-urban areas. In a study of prostate cancer incidence from 1950–2000 in the northern Plains states, investigators found higher mortality in rural compared to urban counties (22), which could also reflect a lower relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer incidence in rural areas. This explanation almost certainly would not apply uniformly across all populations. In Illinois, for example, a pronounced urban/rural gradient in regional/distant stage prostate cancer diagnoses was described, with the highest odds of late-stage diagnosis in the city of Chicago (9). In that study, after controlling for demographic variables, the effect was no longer observed. The authors suggested that the urban/rural gradient might be explained by heterogeneous racial and demographic characteristics across urban and rural areas of Illinois. Future research should focus on region-specific individual- and area-level characteristics that could influence prostate cancer screening behavior.

Findings from this study support the utility of both large- and small-area spatial analyses to assess cancer clustering. Results from the multistate analysis suggested that several primarily rural areas have lower relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer while several primarily urban areas have higher relative risk of localized-stage diagnosis. A separate analysis of cases in Tennessee alone revealed additional clusters with comparatively high relative risks of localized-stage disease that were obscured in the multistate analyses. An analysis of Georgia cases alone eliminated a cluster near the Alabama border that was present in the multistate map. Insights gained from combined spatial analyses within and across regions could inform cancer control efforts at local, regional and national levels.

There are some limitations of this study. We were unable to adjust for individual-level socioeconomic status, which was not available from the cancer registries. Thus, inferences regarding demographic variables in this analysis are ecological and may not reflect case attributes. Second, the data utilized for this study were obtained from multiple cancer registries and are subject to variation in methodology. Within the study region, Georgia and Florida received NAACR gold-level certification, Alabama received silver-level certification, and Tennessee was not certified. Differential case reporting could have affected multistate analyses. Third, the ability to detect clusters among Black males alone was limited by small numbers of cases. Nonetheless, results for Black males were consistent with urban versus rural patterns in the overall analysis.

In summary, in this study, urban residence was a major predictor of localized-stage diagnosis of prostate cancer for both Black and white men. Evidence of continuing racial disparity included higher incidence rates of prostate cancer among Blacks than whites with a lower proportion of Black men diagnosed at localized-stage. Furthermore, clusters with highest relative risks of localized-stage generally had low percent Black population. Encouragingly, positive correlations between percent-Black population and high relative risk of localized stage prostate cancer were found in three states (not Florida). In addition, almost all non-urban clusters with high relative risk of localized-stage cancer had higher than the national percent Black population and most of these clusters had favorable levels of educational attainment or income. These findings may be useful in design and evaluation of cancer control programs effectiveness.

Figure 2.

Spatial clusters with statistically significant relative risk of localized-stage prostate cancer compared to the background incidence rate by individual state – Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee: 1999–2001

* Cases restricted to Black and white males only

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. 2006. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; Cancer facts and figures for African Americans; 2005–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz KL, Crossley-May H, Vigneau FD, Brown K, Banerjee M. Race, socioeconomic status and stage at diagnosis for five common malignancies. Cancer Causes Control. 2003 Oct;14(8):761–766. doi: 10.1023/a:1026321923883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2006. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones BA, Liu WL, Araujo AB, et al. Explaining the race difference in prostate cancer stage at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Oct;17(10):2825–2834. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the united states : Findings from the national program of cancer registries patterns of care study. Cancer. 2008 Aug 1;113(3):582–591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National longitudinal mortality study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 May;20(4):417–435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenlee RT, Howe HL. County-level poverty and distant stage cancer in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 Aug;20(6):989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DC, Litwin MS, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer severity among low income, uninsured men. J Urol. 2009 Feb;181(2):579–583. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLafferty S, Wang F. Rural reversal? Rural-urban disparities in late-stage cancer risk in Illinois. Cancer. 2009 Jun 15;115(12):2755–2764. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prostate cancer rates by state [Internet] 2009 June 8; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/Prostate/statistics/state.htm.

- 11.Oliver MN, Stukenborg GJ. Race and the likelihood of localized prostate cancer at diagnosis among men in 4 southeastern states. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009 Aug;101(8):750–757. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandal R, St-Hilaire S, Kie JG, Derryberry D. Spatial trends of breast and prostate cancers in the United States between 2000 and 2005. Int J Health Geogr. 2009 Sep 29;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKinnon J. Black population: 2000. 2001 August; Available from http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-5.pdf.

- 14.Determining census 2000 tract numbers for HMDA/CRA reporting [Internet] 2006 June 29; Available from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/hmda_cra.html.

- 15.Kulldorff M. A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 1997;26(6):1481. doi: 10.1080/03610927708831932. [cited December 23, 2008] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulldorff M, Huang L, Pickle L, Duczmal L. An elliptic spatial scan statistic. Stat Med. 2006 Nov 30;25(22):3929–3943. doi: 10.1002/sim.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census 2000, summary file 3 [Internet] 2009 August 8; Available from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2002/sumfile3.html.

- 18.Rural-urban continuum codes [Internet] 2004 November 3; Available from http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/RuralUrbanContinuumCodes/

- 19.Kenney JF, Keeping ES. Mathematics of statistics, pt. 2, 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand; 1951. pp. 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe HL, Keller JE, Lehnherr M. Relation between population density and cancer incidence, Illinois, 1986–1990. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Jul 1;138(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver MN, Smith E, Siadaty M, Hauck FR, Pickle LW. Spatial analysis of prostate cancer incidence and race in Virginia, 1990–1999. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Feb;30 2 Suppl:S67–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusiecki JA, Kulldorff M, Nuckols JR, Song C, Ward MH. Geographically based investigation of prostate cancer mortality in four U.S. northern plain states. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Feb;30 2 Suppl:S101–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]