Abstract

Diisocyanate is a leading cause of occupational asthma (OA). Diisocyanate-induced OA is an inflammatory disease of the airways that is associated with airway remodelling. Although the pathogenic mechanisms are unclear, oxidative stress may be related to the pathogenesis of diisocyanate-induced OA. In our previous report, we observed that the expression of ferritin light chain (FTL) was decreased in both of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum of patients with diphenyl-methane diisocyanate (MDI)-induced OA compared to those of asymptomatic exposed controls and unexposed healthy controls. In this study of toluene diisocyanate (TDI)-OA, we found identical findings with increased transferrin and decreased ferritin levels in the serum of patients with TDI-OA. To elucidate whether diisocyanate suppresses FTL synthesis directly, we tested the effect of TDI on the FTL synthesis in A549 cells, a human airway epithelial cell line. We found that haem oxygenase-1 as well as FTL was suppressed by treatment with TDI in dose- and time-dependent manners. We also found that the synthesis of other anti-oxidant proteins such as thioredoxin-1, glutathione peroxidase, peroxiredoxin 1 and catalase were suppressed by TDI. Furthermore, TDI suppressed nuclear translocation of Nrf2 through suppressing the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs); extracellular-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2); p38; and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonists, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone rescued the effect of TDI on HO-1/FTL expression. Collectively, our findings suggest that TDI suppressed HO-1/FTL expression through the MAPK–Nrf2 signalling pathway, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of TDI-induced OA. Therefore, elucidating these observations further should help to develop the therapeutic strategies of diisocyanate-induced OA.

Keywords: asthma, ferritin, HO-1, Nrf2, toluene diisocyanate

Introduction

Diisocyanate chemicals, such as toluene diisocyanate (TDI), diphenyl-methane diisocyanate (MDI) and hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), are highly reactive chemicals used in a variety of chemical manufacturing processes, including the production of polyurethane forms and paints, and among these, TDI is the most commonly identified cause of occupational asthma (OA) [1,2].

TDI-induced OA (TDI-OA) is characterized by hyperresponsiveness, inflammation and remodelling of the airways [3]. Although the pathogenic mechanisms of TDI-OA have not yet been elucidated completely, several immunological and non-immunological mechanisms have been suggested [2,4]. Gathering evidence suggests that diisocyanate binds to airway epithelial cell proteins and are taken up by epithelial cells [5,6]. These interactions lead to airway inflammation comprising cytokine and chemokine production and cellular recruitment [2].

Oxidative stress has been speculated to play an essential role in the pathogenesis of airway inflammation [7]. The airway epithelium is exposed constantly to oxidants in the ambient air, including ozone, nitrogen dioxide, diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke. Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels have been implicated in initiating inflammatory responses in the lungs through a variety of signalling pathways [8]. Therefore, the lung contains many anti-oxidant defences in order to protect itself from oxidant-induced tissue damage. The anti-oxidant defence system in the airway includes glutathione, vitamins C and E as non-enzymatic anti-oxidants, and superoxide dismutases (SODs) and catalase (CAT) as enzymatic anti-oxidants. Recently, haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and small molecular weight redox proteins, such as peroxiredoxin (PRDX) and thioredoxins (TXNs), have also been found to play a crucial role in lung anti-oxidant defence mechanisms [9]. The imbalance in oxidant and anti-oxidant systems has been well known to play a role in a variety of respiratory diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [7,10].

In our recent previous study, using a proteomic approach, we found that the ferritin light chain (FTL) was down-regulated whereas transferrin was up-regulated in the MDI-induced OA group, compared with the asymptomatic exposed control (AEC) group [11]. Ferritin is an iron storage protein consisting of two subunits, a heavy chain and light chain, that sequester iron in the ferric (Fe3+) state [12]. Ferritin synthesis is regulated by intracellular iron at both the transcriptional and translation levels. In addition, ferritin expression is regulated by oxidative stress that acts either directly on gene expression or indirectly via modifications of iron regulatory protein activity [12]. The ability of cells to induce rapid ferritin synthesis prevents the effects of free radical damage to cellular components [12]. Therefore, the dysregulation of ferritin expression could cause tissue damage in the airway, followed by airway inflammatory diseases such as asthma.

HO-1 is the inducible isoform of haem oxygenase and catalyses the degradation of haem, a potent oxidant, to generate biliverdin, iron and carbon monoxide [13]. Biliverdin is converted to bilirubin, a potent endogenous anti-oxidant, while iron is sequestered by ferritin, leading to an additional anti-oxidant effect [13]. CO has anti-inflammatory properties [13], suggesting that HO-1 plays a critical role in defending the lung against inflammatory and oxidant-induced cellular and tissue injury and is considered to be a potential therapeutic target in allergic inflammation [14].

In the present study, we extended our previous clinical findings in patients with TDI-OA and evaluated the mechanism of how the regulation of FTL expression is associated with the pathogenesis of diisocyanate-induced OA.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

We enrolled 74 patients with TDI-OA, determined by positive responses to TDI bronchoprovocation tests. The control subjects included 144 asymptomatic exposed subjects (AECs) from similar working environments (i.e. spray-painting or polishing in the furniture, musical instrument or car industries). Ninety-two unexposed healthy controls (NCs) were recruited from among out-patients at Ajou University Hospital in Suwon, Korea. Atopy was determined by a positive skin prick test to at least one common inhalant allergen, such as house dust mites, tree and pollen mixtures, mugwort, ragweed pollens or Alternaria (Bencard, Bradford, UK). Sera from all participants were collected at initial examination. All subjects underwent an interview, chest radiography and skin prick test with common inhalant allergens. To confirm TDI-OA, we subjected patients to lung function measurements and inhalation challenges with methacholine and TDI. The methacholine challenge and TDI bronchoprovocation tests were performed as described previously [15,16]. Their clinical features are summarized in Table 1. All participants provided their informed consent, which was regulated by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Medical Center.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the study subjects.

| TDI-OA (n = 74) | AEC (n = 144) | NC (n = 92) | TDI-OA versus AEC | TDI-OA versus NC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 48 (65·8%) | 104 (72·2%) | 27 (32·1%) | 0·326 | <0·001 |

| Age (years) | 42·5 ± 9·9 | 41·2 ± 8·3 | 29 ± 6·2 | 0·354 | <0·001 |

| Working duration (years) | 6·8 ± 4·2 | 11·6 ± 6·7 | – | 0·004 | NA |

| % predicted FEV1 | 82·9 ± 23·3 | – | – | NA | NA |

| PC20 (mg/ml) | 6·1 ± 9·2 | – | – | NA | NA |

| Log total IgE (IU/ml) | 4·8 ± 1·4 | 4·5 ± 1·4 | 3·5 ± 1·4 | 0·227 | 0·003 |

| Atopy (%) | 27 (44·3%) | – | 6 (37·5%) | NA | 0·627 |

| Smoking history (%) | 19 (28·4%) | 53 (42·7%) | 0 (0%) | 0·117 | 0·419 |

All values were presented as mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Pearson's χ2 and t-test. AEC, asymptomatic exposed workers; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; Ig, immunoglobulin; NC, unexposed healthy control; TDI-OA, toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma.

Measurement of ferritin and transferrin in sera

The serum levels of FTL (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX, USA) and transferrin (Alpha Diagnostic International) in the subjects from the 74 TDI-OA, 144 AEC and 92 NC groups were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, as described previously [11].

Materials

TDI, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), and SB203580 were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). TDI was thawed in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) (1 : 20, v/v). When we treated cells with TDI, we treated with an equivalent amount of DMSO as a control. Tin-protoporphyrin-IX (SnppIX) was obtained from Porphyrin Products (Logan, UT, USA). U0126 and SP600125 were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Rosiglitazone and 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) were purchased from Biomol (Cayman, MI, USA).

Cell culture

A549 cells and Beas-2B cells, human airway epithelial cell lines, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). They were grown in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from A549 cells using an Easy-BLUE Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnologies, Seoul, Korea). Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse-transcribed using the oligodeoxythymidylic acid (oligo-dT) primer and Moloney murine leukaemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 42°C for 90 min. Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7500 instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification kinetics were recorded as sigmoid progress curves for which fluorescence was plotted against the number of amplification cycles. The threshold cycle number (CT) was used to define the initial amount of each template. The CT was the first cycle for which a detectable fluorescence signal was observed. The mRNA expression levels were determined and standardized to that of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Preparation of whole, cytosolic and nuclear extracts

The whole cell lysates were prepared by radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0·25% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)] containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared using 200 µl of lysis buffer [10 mM HEPES, pH 7·9, 10 mM KCl, 0·1 mM EDTA, 0·1 mM ethyleneglycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)] and incubated on ice for 15 min. At the end of this incubation, 10 µl of 10% NP-40 was added and the tube was vortexed for 10 s. After centrifugation at 12 000 g for 10 min at 4°C, supernatants were used as cytosolic extract. The pellets were processed further to obtain nuclear extracts. The pellets were resuspended in the extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 M glycerol, 0·4 M Nacl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Nuclear extracts were isolated by centrifugation at 12 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatants were stored at 80°C until used for Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

The cell extracts were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked in blocking solution [5% non-fat dried milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)] for 2 h at room temperature and then probed with anti-HO-1 (Stressgen Biotechnologies, Victoria, BC, Canada), anti-PRDX1, anti-TXN-1, anti-Nrf2, anti-actin, anti-ferritin light chain, anti-lamin B (Santa Cruz Technology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-CAT (Ab Frontier, Seoul, Korea), anti-extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK), anti-phospho ERK, anti-p38, anti-phospho p38, anti-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), anti-phospho JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) and anti-tubulin (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0·1% Tween-20 (PBS-T), the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing an additional three times in PBS-T, the membranes were developed using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and exposed to Kodak X-ray film.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA for Nrf2–ARE binding was performed as described previously [17]. In brief, a synthetic double-strand oligonucleotide corresponding to a human HO-1 ARE site (in italics), 5′-GCATTTCTGCTGCGTCATGTTTGGGAGG-3′ was radiolabelled with [γ32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and purified using Sephadex G-25 Quick Spin Columns (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). DNA–protein complexes were separated on 6% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels in Tris/glycine buffer, pH 8·3. The dried gels were exposed to X-ray film.

Immunocytochemistry

Two × 104 A549 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h at 37°C. After washing briefly, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min and permeabilized with 0·1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. After washing three times in PBS, the cells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with anti-Nrf2 antibody for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS, and reacted with a fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody (Cappel, Durham, NC, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was evaluated using t-test, analysis of variance (anova) or Mann–Whitney U-test unless stated otherwise (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Comparison of serum ferritin and transferrin

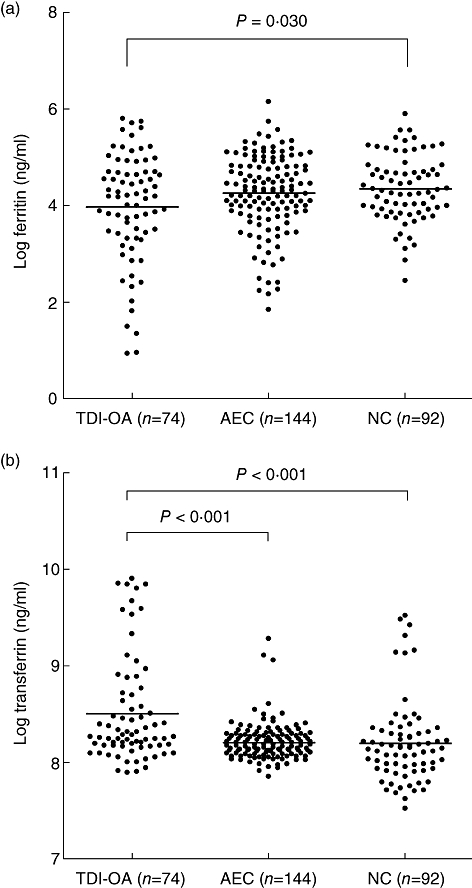

Table 1 summarizes the relevant demographic data. The patients with TDI-OA and asymptomatic exposed subjects (AEC) groups had significantly older age and male predominance. In addition, exposure duration was significantly longer in the AEC than the TDI-OA group. Although smoking history was predominant in the TDI-OA and AEC groups compared to those of unexposed healthy controls (NC), there were no significant differences (P = 0·419, Table I). The serum ferritin level of patients with TDI-OA was lowered significantly compared to those of AEC and NC, while the serum transferrin level was significantly higher than those of two control groups (P < 0·05, respectively, Fig. 1), which is in agreement with our previous study of patients with MDI-OA [11].

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the serum concentrations of log ferritin (a) and log transferrin (b) in subjects with toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma (TDI-OA), asymptomatic exposed control (AEC) and unexposed healthy controls (NC). Statistical significances were noted in both ferritin and transferrin levels among the three study groups (P < 0·05). All values were presented as log-transformed. Horizontal bars indicate mean value of each group. P-value was applied to analysis of variance (anova) with Bonferroni. AEC, asymptomatic exposed workers.

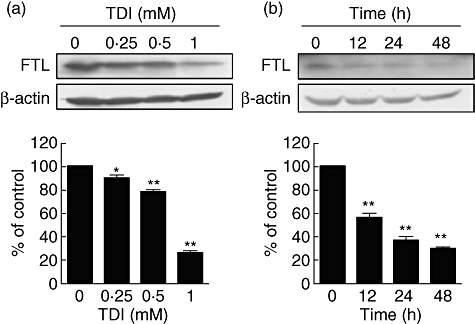

TDI down-regulated FTL expression in A549 cells

To evaluate the direct effect of TDI on the expression of ferritin light chain (FTL) in airway epithelial cells, we performed Western blot analysis in A549 cells. When A549 cells were incubated with TDI, FTL expression was down-regulated in time- and dose-dependent manners (Fig. 2), suggesting that TDI down-regulates FTL expression in airway epithelial cells directly. We did not find any cytotoxicity by TDI in our experimental condition (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) down-regulated ferritin light chain (FTL) expression in A549 cells. (a) A549 cells were incubated with the indicated doses of TDI for 48 h, and then Western blot against FTL was performed. (b) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for the indicated times, and then Western blot against FTL was performed. The intensities of Western blot were analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01 versus control.

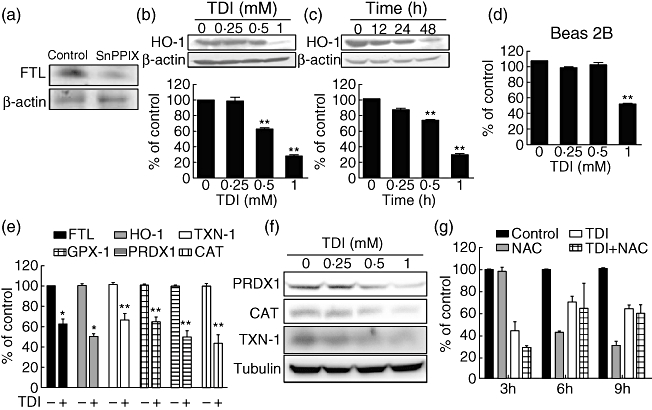

TDI down-regulated HO-1 expression in A549 cells

The expression of ferritin is regulated in part by intracellular iron levels at both the transcriptional and translational levels [12]. Moreover, HO-1 generates intracellular iron as haem metabolites [18]. Tin-protoporphyrin-IX (SnppIX), a specific inhibitor of HO-1, suppressed FTL expression in A549 cells (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the activity of HO-1 is linked to FTL expression. We performed Western blot analysis to evaluate whether TDI also regulates HO-1 expression in airway epithelial cells. Interestingly, TDI also down-regulated HO-1 expression in A549 cells in dose- and time-dependent manners (Fig. 3b,c). In addition, TDI also down-regulated HO-1 expression in Beas-2B cells (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, real-time RT–PCR and Western blot analysis indicated that TDI also down-regulated the mRNA and protein levels of several anti-oxidant proteins such as TXN-1, GPX-1, PRDX1 and CAT, as well as FTL and HO-1 (Fig. 3e,f), suggesting that TDI down-regulates the expression of anti-oxidant proteins in airway epithelial cells. Previous reports demonstrated that TDI exposure induces ROS generation [19,20]. Oxidative stress such as ROS has been known to up-regulate anti-oxidant enzymes [18,21]. To identify the effect of ROS generated by TDI on the regulation of anti-oxidant proteins, A549 cells were treated with TDI in the absence or presence of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger [22], and then real-time RT–PCR analysis was performed. NAC did not abrogate TDI's down-regulation of HO-1 expression; rather, it caused the expression of HO-1 to be reduced further (Fig. 3g), suggesting that ROS generated by TDI are independent of TDI's effect on down-regulating anti-oxidant protein expression and that the other properties of TDI could down-regulate anti-oxidant proteins.

Fig. 3.

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) down-regulated the expression of several anti-oxidant proteins in A549 cells. (a) A549 cells were incubated with 20 µM SnPP IX for 3 h, and then Western blot against ferritin light chain (FTL) was performed. (b) A549 cells were incubated with the indicated doses of TDI for 48 h, and then Western blot against haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) was performed. (c) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for the indicated times, and then Western blot against HO-1 was performed. The intensities of Western blot were analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. (d) Beas 2B cells were incubated with indicated doses of TDI for 48 h, and then Western blot against HO-1 was performed. Intensities of Western blot were then analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. (e) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was performed as described in Methods. (f) A549 cells were incubated with the indicated doses of TDI for 48 h, and then Western blot against peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1), catalase (CAT) and thioredoxin 1 (TXN-1) was performed. (g) A549 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 1 mM TDI or 20 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for the indicated times, then real-time RT–PCR was performed. The values were normalized by those of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 versus control.

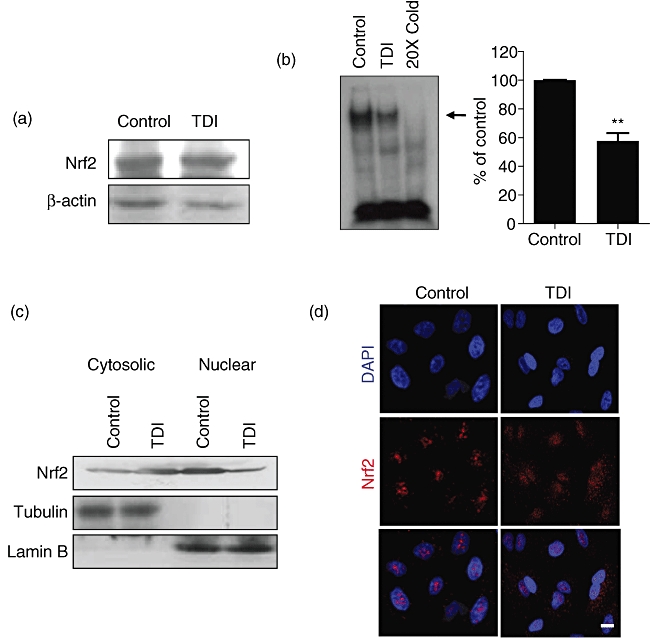

TDI inhibited Nrf2 translocation into nucleus

The expression of several anti-oxidant proteins is regulated by transcription factor Nrf2 by binding the anti-oxidant response element (ARE) in the promoter of target genes [21]. We speculated that TDI could regulate the expression of anti-oxidant proteins by regulating the expression or translocation of Nrf2. Initially, we performed Western blot analysis to identify the expression of Nrf2. As shown in Fig. 4a, the total level of Nrf2 was not changed by TDI treatment. Next, we determined the change of binding between Nrf2 and the ARE region of HO-1 promoter by EMSA. EMSA analysis indicated that the treatment of TDI suppressed the binding of Nrf2 to the ARE region of HO-1 promoter (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, we determined the effect of TDI on Nrf2 translocation between the nuclear and cytosolic fractions. In our experimental condition, Western blot analysis indicated that Nrf2 was located mainly in the nuclear fraction in the resting state, while Nrf2 was located mainly in the cytosolic fraction in the TDI-treated state in A549 cells (Fig. 4c). Immunofluorescence data also indicated that Nrf2 was located mainly in the nucleus in the resting state, while Nrf2 was located both in the nucleus and cytoplasma in the TDI-treated state (Fig. 4d), suggesting that TDI suppresses Nrf2–ARE binding by inhibiting the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus in A549 cells.

Fig. 4.

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) inhibited the translocation of Nrf2. (a) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then Western blot against Nrf2 was performed. (b) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described in Methods. The arrow indicates the binding between Nrf2 and ARE of haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) 1. The intensities of the binding between Nrf2 and ARE of HO-1 were analysed. (c) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then separated into nuclear and cytosolic fractions as described in Methods. Western blot against Nrf2 was performed. Tubulin and lamin B were used as controls for the cytosolic fraction and nuclear fraction, respectively. (d) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then immunofluorescence assay for Nrf2 (red) was performed as described in Methods. **P < 0·01 versus control.

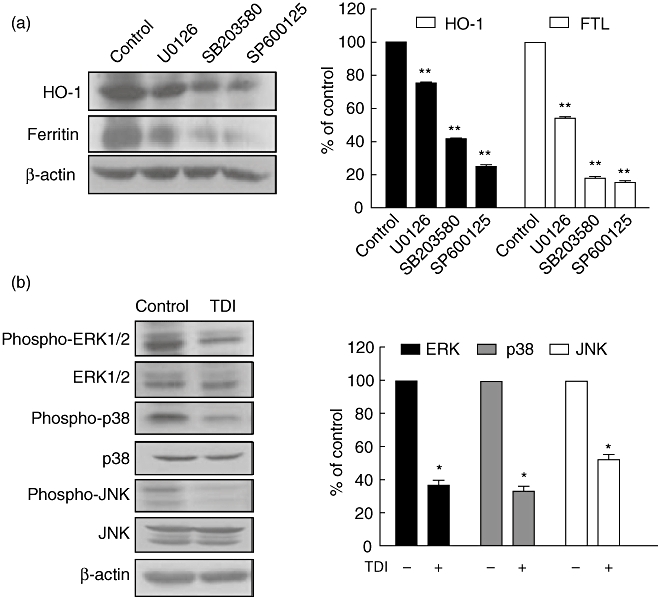

TDI inhibited the activation of MAPKs

The translocation of Nrf2 is regulated by several upstream signalling kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC), phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs; ERK1/2, JNK and p38) [23]. In order to confirm this, A549 cells were incubated with MAPK inhibitors: U0126 (an inhibitor of ERK1/2), SB203580 (an inhibitor of p38) and SP600125 (an inhibitor of JNK), respectively. Inhibition of MAPKs by specific inhibitors down-regulated the expression of HO-1/FTL (Fig. 5a), suggesting that the activities of MAPKs regulate the downstream expression of Nrf2, such as HO-1 and FTL. Next, when A549 cells were incubated with TDI, we observed that the phosphorylation of MAPKs was suppressed (Fig. 5b), suggesting that TDI down-regulated HO-1/FTL expression by inhibiting the activity of MAPKs.

Fig. 5.

Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) inhibited the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). (a) A549 cells were incubated with 20 µM U0126, 20 µM SB203580 or 20 µM SP600125 for 3 h, and then Western blot against haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and ferritin light chain (FTL) was performed. The intensities of Western blot were analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. (b) A549 cells were incubated with 1 mM TDI for 3 h, and then Western blot was performed. The intensities of Western blot were analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01 versus control.

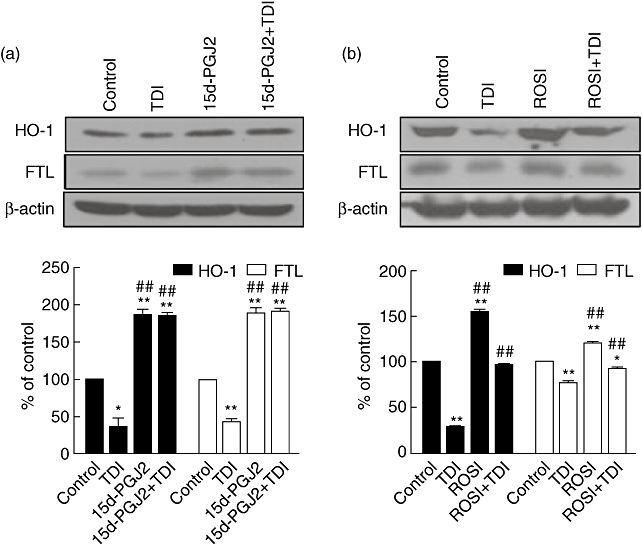

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonists rescued the effect of TDI on the expression of HO-1/FTL

15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2), a type of PPAR-γ agonist, has been known to up-regulate HO-1 expression via the MAPK signalling pathways [18,24]. To evaluate whether PPAR-γ agonists could rescue the effect of TDI on the expression of HO-1/ferritin, A549 cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 in the presence of TDI. The effect of TDI on the expression of HO-1/FTL was rescued by 15d-PGJ2, which further up-regulated the expression of HO-1/FTL higher than the basal level of HO-1/FTL (Fig. 6a). In addition, rosiglitazone, another PPAR-γ agonist, also up-regulated HO-1/FTL and rescued the effect of TDI on the expression of HO-1/FTL, although it was less effective than 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone could rescue the effect of toluene diisocyanate (TDI) on the expression of haem oxygenase-1/ferritin light chain (HO-1/FTL). A549 cells were incubated with 15 µM 15d-PGJ2 (a) or 15 µM rosiglitazone (ROSI) (b) in the absence or presence of 1 mM TDI for 48 h, and then Western blot against FTL and HO-1 was performed. The intensities of Western blot were analysed and normalized by those of β-actin. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01 versus control; ## P < 0·01 versus TDI-treated samples.

Discussion

Increased oxidative stress has been implicated in the aetiology of a number of acute and chronic diseases, including asthma, linked to exposure to environmental toxicants. Although the pathogenic mechanism of diisocyanate-induced OA is not currently understood completely, oxidative stress is likely to be a major candidate for explaining the pathogenesis of diisocyanate-induced OA [25,26]. A previous report demonstrated that TDI exposure induces ROS generation [19]. We also observed that human serum albumin-conjugated TDI induced ROS generation in A549 cells [20]. Furthermore, in our recent previous report, we found that decreased ferritin expression in association with increased transferrin was noted in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum of patients with MDI-OA [11]. In this study of TDI-OA, we found identical findings with increased transferrin and decreased ferritin levels in the serum of patients with TDI-OA. Ferritin and transferrin have different roles; ferritin is used for detoxification during oxidative stress-induced inflammation [27], whereas hypotransferrinaemia is associated with resistance to oxidant injury [28]. These findings suggest that the imbalance between oxidative stress and the anti-oxidant system may contribute to the development of airway inflammation in TDI-OA subjects. In the present study, however, we could not exclude the influence of smoking on the oxidative stress of subjects, although there were no significant differences among groups statistically.

Regarding the mechanism of how ferritin could be decreased with TDI exposure, in this study we observed that TDI down-regulated FTL expression in A549 cells, a human airway epithelial cell line. In addition several anti-oxidant proteins, including HO-1, TXN-1, GPX-1, PRDX1 and CAT, were also down-regulated by TDI. Several anti-oxidant proteins that we observed in this study are regulated by Nrf2 transcription factor. Nrf2 is a member of the family of basic leucine zipper transcription factors and recognizes ARE in the promoter of target genes [21]. It is well known that Nrf2 regulates the expression of a network of cytoprotective enzymes, including anti-oxidant enzymes such as SOD, HO-1, PRDX, GPX and CAT, resulting in protection against toxicity following exposure to oxidative chemicals. HO-1 (an Nrf2 target enzyme) expression protects cells from physical, chemical and biological stress [18]. Disruption of the Nrf2 gene leads to susceptibility to severe allergen-induced asthma in mice [29]. HO-1-deficient mice developed severe physiological lung dysfunction [30]. Furthermore, polymorphisms of the HO-1 promoter associated with reduced HO-1 expression have been linked recently with increased susceptibility to a variety of respiratory diseases, including emphysema and pneumonia [31,32]. Accordingly, inhibition of inducible anti-oxidant proteins upon stress could aggravate the severity of diseases. In the present study TDI inhibited the expression of several anti-oxidant proteins, which may result in OA. In agreement with our speculation, a previous study has demonstrated a lowering of the intracellular glutathione concentration following TDI exposure with subsequent symptoms of oxidative stress to those cells [33].

The transcriptional activation of Nrf2 is regulated by several upstream signalling kinases [23]. In our experimental condition, the inhibition of MAPKs suppressed Nrf2/ARE-driven HO-1/FTL expression. Furthermore, TDI inhibited the phosphorylation of MAPKs, which may cause the suppression of Nrf2/ARE-driven HO-1/FTL expression. Currently, we could not demonstrate how TDI suppressed MAPK activity. However, TDI binds to airway epithelial cell proteins and is taken up by epithelial cells [5,6], which may modulate several signalling molecules and cause the inhibition of MAPKs. Further studies will be needed to elucidate how TDI modulates intracellular signalling pathways.

HO-1 is known to be up-regulated by a variety of stress stimuli, including ROS, ultraviolet A radiation, heat shock and heavy metals, endogenous mediators including 15d-PGJ2, lipoxin A4 and therapeutic compounds such as curcumin and resveratrol [18]. Among them, the effect of 15d-PGJ2 on HO-1 induction was reported to be involved in MAPKs and Nrf2 activation [18]. 15d-PGJ2 has been recognized as the endogenous ligand for PPAR-γ and is thought to be responsible for many of its anti-inflammatory actions [34]. Gathering evidence indicates that PPAR-γ acts as an anti-inflammatory gene induced in response to inflammatory cell activation [35]. Thus, PPAR-γ agonists have been suggested as a novel anti-inflammatory target for airway diseases such as asthma and COPD [35]. In the present study, we demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 could rescue the effect of TDI on the expression of HO-1/FTL. It has been proposed that the effect of 15d-PGJ2 on the induction of HO-1 is independent of PPAR-γ[36]. We also observed that 15d-PGJ2 is more effective than rosiglitazone. However, rosiglitazone was also capable of rescuing the effect of TDI, although less effective than 15d-PGJ2. In addition, it was also reported that epigallocatechin-3-gallate, which is known to be an inducer of HO-1 [18,37], protects TDI-induced airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma [19].

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that TDI inhibited FTL/HO-1 expression in A549 cells directly by regulating the MAPK–Nrf2 signalling pathway, which may contribute to the development of airway inflammation in TDI-OA. In addition, 15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone rescued the inhibitory effect of TDI on FTL/HO-1 expression, suggesting that these agents and the elucidation of these signalling pathways should help to develop the therapeutic target for treatment of TDI-OA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation through Chronic Inflammatory Disease Research Center Ajou University Grant (R13-2003-019 to S. M. P.) and a grant of the Korean Health 21 R&D project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, ROK (A030001 to H. S. P.).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lee CT, Ylostalo J, Friedman M, Hoyle GW. Gene expression profiling in mouse lung following polymeric hexamethylene diisocyanate exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;205:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisnewski AV, Redlich CA. Recent developments in diisocyanate asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1:169–75. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000011003.36723.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mapp CE, Boschetto P, Zocca E, et al. Pathogenesis of late asthmatic reactions induced by exposure to isocyanates. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1987;23:583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park HS, Cho SH, Hong CS, Kim YY. Isocyanate-induced occupational asthma in far-east Asia: pathogenesis to prognosis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:198–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange RW, Day BW, Lemus R, Tyurin VA, Kagan VE, Karol MH. Intracellular S-glutathionyl adducts in murine lung and human bronchoepithelial cells after exposure to diisocyanatotoluene. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:931–6. doi: 10.1021/tx990045h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisnewski AV, Srivastava R, Herick C, et al. Identification of human lung and skin proteins conjugated with hexamethylene diisocyanate in vitro and in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2330–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowler RP, Crapo JD. Oxidative stress in allergic respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:349–56. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkham P, Rahman I. Oxidative stress in asthma and COPD: antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:476–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kode A. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airway diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:222–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riedl MA, Nel AE. Importance of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and treatment of asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:49–56. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f3d913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hur GY, Choi GS, Sheen SS, et al. Serum ferritin and transferrin levels as serologic markers of methylene diphenyl diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. Ferritin in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredenburgh LE, Perrella MA, Mitsialis SA. The role of heme oxygenase-1 in pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:158–65. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0331TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pae HO, Lee YC, Chung HT. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide: emerging therapeutic targets in inflammation and allergy. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2008;2:159–65. doi: 10.2174/187221308786241929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye YM, Kim CW, Kim HR, et al. Biophysical determinants of toluene diisocyanate antigenicity associated with exposure and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:885–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HS, Kim HY, Nahm DH, Son JW, Kim YY. Specific IgG, but not specific IgE, antibodies to toluene diisocyanate–human serum albumin conjugate are associated with toluene diisocyanate bronchoprovocation test results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:847–51. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogborne RM, Rushworth SA, O'Connell MA. Alpha-lipoic acid-induced heme oxygenase-1 expression is mediated by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human monocytic cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2100–5. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000183745.37161.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrandiz ML, Devesa I. Inducers of heme oxygenase-1. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:473–86. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SH, Park HJ, Lee CM, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate protects toluene diisocyanate-induced airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1883–90. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hur GY, Kim SH, Park SM, et al. Tissue transglutaminase can be involved in airway inflammation of toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:786–94. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osburn WO, Kensler TW. Nrf2 signaling: an adaptive response pathway for protection against environmental toxic insults. Mutat Res. 2008;659:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji KA, Yang MS, Jou I, Shong MH, Joe EH. Thrombin induces expression of cytokine-induced SH2 protein (CIS) in rat brain astrocytes: involvement of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and lipoxygenase. Glia. 2004;48:102–11. doi: 10.1002/glia.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JS, Surh YJ. Nrf2 as a novel molecular target for chemoprevention. Cancer Lett. 2005;224:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez-Maqueda M, El Bekay R, Alba G, et al. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces heme oxygenase-1 gene expression in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner in human lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21929–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown WE, Burkert AL. Biomarkers of toluene diisocyanate exposure. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 2002;17:840–5. doi: 10.1080/10473220290107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan SG, Mali RG, Mehta AA. Effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. seed extract on toluene diisocyanate-induced immune-mediated inflammatory responses in rats. J Immunotoxicol. 2007;4:85–96. doi: 10.1080/15476910701337472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juckett MB, Balla J, Balla G, Jessurun J, Jacob HS, Vercellotti GM. Ferritin protects endothelial cells from oxidized low density lipoprotein in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:782–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang F, Coalson JJ, Bobb HH, Carter JD, Banu J, Ghio AJ. Resistance of hypotransferrinemic mice to hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1999;277:L1214–L1223. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. J Exp Med. 2005;202:47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fredenburgh LE, Baron RM, Carvajal IM, et al. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 expression in the lung parenchyma exacerbates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury and decreases surfactant protein-B levels. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2005;51:513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Exner M, Minar E, Wagner O, Schillinger M. The role of heme oxygenase-1 promoter polymorphisms in human disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1097–104. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuda H, Okinaga S, Yamaya M, et al. Association of susceptibility to the development of pneumonia in the older Japanese population with haem oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e17. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lantz RC, Lemus R, Lange RW, Karol MH. Rapid reduction of intracellular glutathione in human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to occupational levels of toluene diisocyanate. Toxicol Sci. 2001;60:348–55. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/60.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. 15d-PGJ2: the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin? Clin Immunol. 2005;114:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belvisi MG, Hele DJ, Birrell MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists as therapy for chronic airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim HJ, Lee KS, Lee S, et al. 15d-PGJ2 stimulates HO-1 expression through p38 MAP kinase and Nrf-2 pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;223:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owuor ED, Kong AN. Antioxidants and oxidants regulated signal transduction pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:765–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]