Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can super-infect persistently infected hosts despite CMV-specific humoral and cellular immunity; however, how it does so remains undefined. Here, we demonstrate that super-infection of rhesus CMV-infected rhesus macaques (RM) requires evasion of CD8+ T cell immunity by virally-encoded inhibitors of MHC-I antigen presentation, particularly the homologues of human CMV US2, 3, 6 and 11. In contrast, MHC-I interference was dispensable for primary infection of RM, or for the establishment of a persistent secondary infection in CMV-infected RM transiently depleted of CD8+ lymphocytes. These findings demonstrate that US2-11 glycoproteins promote evasion of CD8+ T cells in vivo thus supporting viral replication and dissemination during super-infection, a process that complicates the development of preventative CMV vaccines, but that can be exploited for CMV-based vector development.

A general characteristic of the adaptive immune response to viruses is its ability to prevent or rapidly extinguish secondary infections by identical or closely related viruses. A notable exception is the herpesvirus family member CMV, which can repeatedly establish persistent infection in immunocompetent hosts (1-3). Sequential infections are likely the reason for the presence of mutiple human CMV (HCMV) genotypes in the human host (4). This ability to establish secondary persistent infections despite the pre-existence of persistent virus (heretofore referred to as “super-infection”) is particularly remarkable since healthy CMV-infected individuals develop high titer neutralizing antibody responses and manifest very high frequency CD4+ and CD8+ CMV-specific T cells responses (>10% of circulating memory T cells can be CMV-specific) (5). This evasion of pre-existing immunity has frustrated attempts to develop preventative CMV vaccines (6, 7), but can be exploited for the development of CMV vectors capable of repeatedly initiating de novo T cell responses to heterologous pathogens in CMV positive hosts (3).

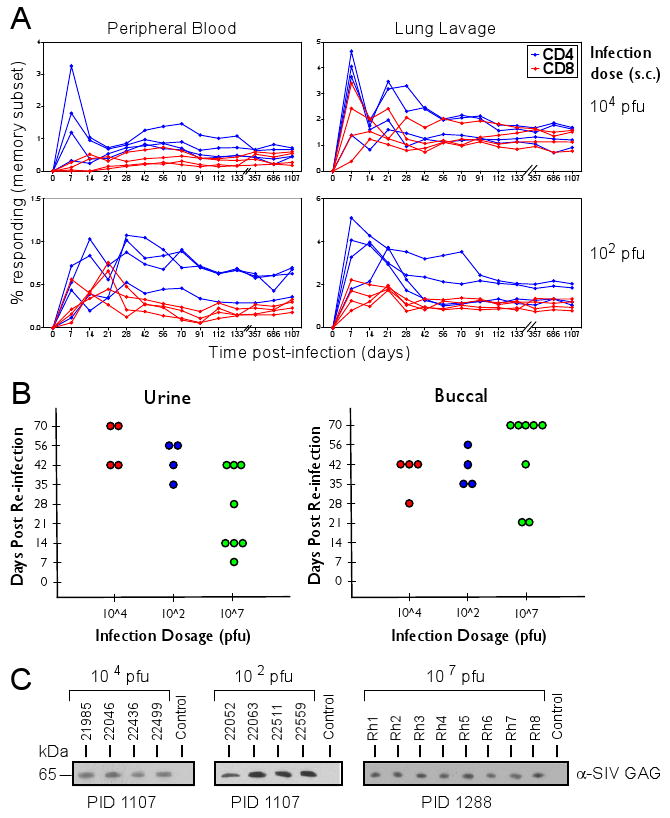

The biologic importance of this super-infection capability has prompted our investigation of its extent and mechanism. We previously showed that inoculation of RhCMV+ RM with 107 PFU of genetically modified RhCMV (strain 68-1) expressing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) antigens resulted in super-infection manifested by the persistent shedding of the genetically modified CMV in the urine and saliva and by the induction and long term maintenance of de novo CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses specific for the SIV insert (3). To determine whether RhCMV would be able to overcome immunity at lower, more physiologic doses of infection, as reported for HCMV (7), a recombinant RhCMV containing a loxP-flanked expression cassette for SIVgag (RhCMV(gagL), fig. S1) was inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) at doses of 104 or 102 plaque forming units (PFU) into four RM naturally infected by RhCMV, as manifested by the presence of robust RhCMV-specific T cell responses (table S1A). The SIVgag-specific T cell responses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or in broncho-alveolar lavage lymphocytes (BAL) were monitored by flow cytometric analysis of intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) (fig. S2, S3) after stimulation with consecutive overlapping 15-mer peptides corresponding to SIVgag (21). Reduction of the inoculating dose had minimal impact on super-infection dynamics: all animals developed SIVgag-specific T cell responses within two weeks (Fig. 1A), and secretion of SIVgag-expressing virus in urine or buccal swabs was observed within 4-10 weeks of infection in both cohorts (Fig. 1B). The time to first detection of secreted virus in these low dose challenged RM was not materially different from that of eight RhCMV+ animals infected with 107 PFU of RhCMV(gagL) (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the SIVgag-specific T cell responses and RhCMV(gagL) secretion were stable for more than three years regardless of initial dose (Fig. 1A,C). These data indicate that, consistent with HCMV in humans, RhCMV is able to overcome high levels of CMV-specific immunity and to establish secondary persistent infections, even with low doses of challenge virus.

Fig. 1.

Re-infection of RhCMV-positive animals is independent of viral dose. (A) At day 0, two cohorts of four RhCMV+ animals each were infected s.c. with 102 or 104 PFU of RhCMV(gagL). The SIVgag-specific T cell responses in PBMC or in BAL were monitored by flow cytometric analysis of ICCS for CD69 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α (21) (fig. S2, S3). (B) Day of first detection of SIVgag-expressing virus in the urine or buccal swabs of each animal in the two cohorts shown in (A). Also included are results from a third cohort of eight RhCMV+ animals inoculated with 107 PFU of RhCMV(gagL). Expression of SIVgag was determined by immunoblot using anti-SIVgag antibody from viral co-cultures (21). Each circle represents an individual animal. (C) Longterm secretion of SIVgag-expressing virus. Urine was isolated at the indicated days post-infection (PID) from each of the RhCMV(gagL)-infected RM and SIVgag-expression was detected from co-cultured virus by immunoblot. For control, a RhCMV-positive animal that did not receive RhCMV(gagL) was included.

We hypothesized that an essential step during CMV super-infection is the ability of the virus to clear an initial immunological checkpoint. A likely candidate for such an immunological barrier is CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL), because they are crucial for controlling CMV-associated diseases (8). The importance of CTL control for CMV is also suggested by viral expression of multiple proteins that inhibit presentation of viral peptide antigens to CD8+ T cells via major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules (9). HCMV encodes at least four related glycoproteins, each with a unique mechanism to prevent antigen presentation: US2 and US11 mediate the retrograde translocation of MHC-I into the cytosol for proteasomal destruction (10), US3 retains MHC-I in the endoplasmic reticulum by interfering with chaperone-controlled peptide loading (11), and US6 inhibits the translocation of viral and host peptides across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane by the dedicated peptide transporter TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) (12). RhCMV encodes sequence and functional homologues of these genes in a genomic region spanning Rh182 (US2) to Rh189 (US11) (fig. S1) (13). Furthermore, the Rh178 gene encodes the RhCMV-specific viral inhibitor of heavy chain expression (VIHCE) which prevents signal-sequence dependent translation/translocation of MHC-I (14).

To determine whether MHC-I interference and CTL evasion played a role in the ability of CMV to super-infect CMV+ animals, we replaced the entire RhUS2-11 region with a SIVgag expression cassette using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis resulting in virus ΔUS2-11(gag) (21). We also deleted Rh178 to generate ΔVIHCEΔUS211(gag) (fig. S1). We previously showed that MHC-I expression is partially restored upon US2-11 deletion whereas additional deletion of Rh178 fully restores MHC-I expression in RhCMV-infected fibroblasts (14). In vitro analysis showed that all viruses were deleted for the targeted RhCMV ORFs, did not contain any unwanted mutations, and replicated comparably to WT RhCMV (fig. S4, S5). First, we examined whether these viruses were able to infect animals that were CMV-naïve as shown by lack of CMV-specific T cell responses (table S1B). Three groups of animals were challenged with 107 PFU of each ΔUS2-11(gag) (n=2), ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) (n=2) or BAC-derived (wildtype) RhCMV(gag) (n=2). T cell responses against both CMV and SIVgag in PBMC and against SIVgag in BAL were comparable between animals infected with the deletion mutants and the wildtype RhCMV(gag) control (Fig. 2A). Moreover, all animals secreted SIVgag-expressing virus from day 56 onward for the duration of the experiment (>700 days) (Fig. 2B). PCR analysis of DNA isolated from urine co-cultured virus at day 428 confirmed that the secreted viruses lacked the respective gene regions and were able to persist in the host (Fig. 2C). Together these results show that viral MHC-I interference is dispensable for primary infection and the establishment and maintenance of persistent infection, despite the development of a substantial CMV-specific T cell response.

Fig. 2.

Interference with MHC-I assembly is not required for primary infection of CMV-naïve animals. Three cohorts of two RM each were inoculated s.c. with 107 PFU of recombinant ΔUS2-11(gag), ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) or RhCMV(gag). (A) The RhCMV-specific T cell response in PBMC and the SIVgag-specific T cell response in PBMC and BAL were determined at the indicated days post infection using overlapping peptides to RhCMV immediate early genes IE1 and IE2 (IE) or SIVgag by flow cytometric analysis of ICCS for CD69, TNFα and IFNγ (21) (fig. S2, S3). (B) Immunoblot of RhCMV-IE2 or SIVgag expressed in co-cultures of urine samples obtained from animals infected with ΔUS2-11(gag) or ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag). The IE2-blot confirms that the animals were negative for RhCMV prior to infection consistent with results from T cell assays (table S1B). (C) PCR-analysis of viral genomic DNA isolated from viral co-cultures at 428 days post infection. The presence or absence of indicated open reading frames (ORFs) was determined by PCR using specific primers (21). One of the animals infected with RhCMV(gag) served as control.

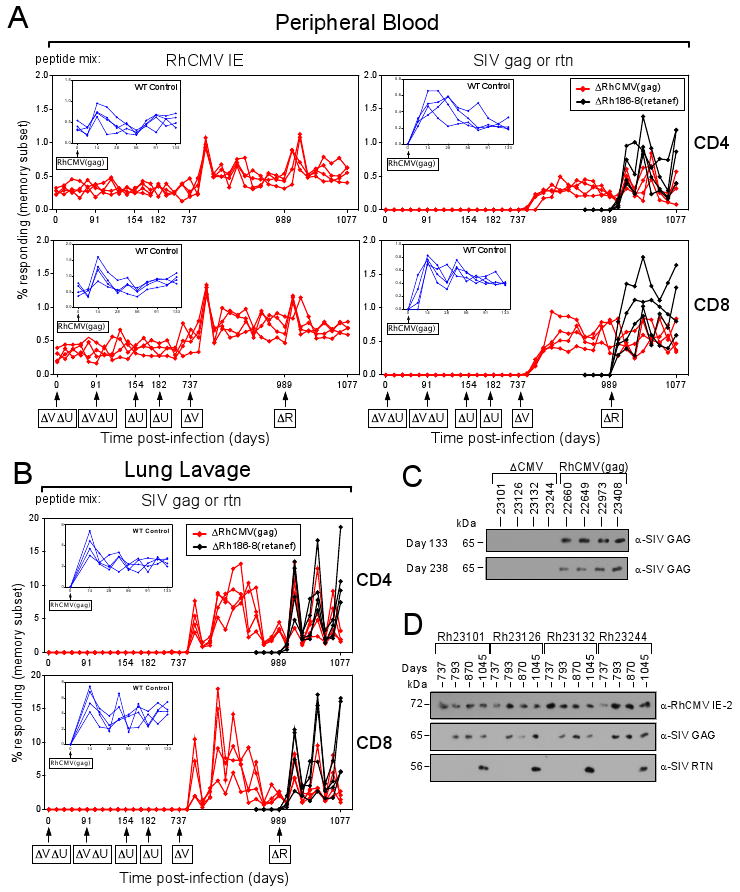

To examine whether viral MHC-I interference was required for super-infection of RhCMV+ RM, we challenged two cohorts of four naturally infected RM each with 107 PFU of ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) or RhCMV(gag). All animals displayed immediate early gene (IE)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses prior to challenge (Fig. 3A; table S1C). In keeping with previous results (3), RM inoculated with wildtype RhCMV(gag) developed a SIVgag-specific immune response (Fig. 3A,B inset) and secreted SIVgag-expressing virus (Fig. 3C). In contrast, we did not detect SIVgag-specific T cell responses in PBMC or BAL in RM inoculated with ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag), even following repeated inoculation (Fig. 3A,B), and SIVgag-expressing virus was not detected in secretions (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that MHC-I interference was essential for super-infection. Inoculation of the same animals with ΔUS2-11(gag), and later, ΔVIHCE(gag) demonstrated that super-infection required the conserved US2-11 region but not the VIHCE region. The development of SIVgag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in blood and BAL (Fig. 3A,B), as well as the boosting of pre-existing RhCMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in blood (Fig. 3A), or shedding of SIVgag-expressing RhCMV (Fig. 3D) were only detectable after challenge with ΔVIHCE(gag) but not with ΔUS2-11(gag).

Fig. 3.

US2-11 deleted RhCMV is unable to super-infect RhCMV+ rhesus macaques. (A) A cohort of four RhCMV+ RM was inoculated s.c. with 107 PFU of ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) (ΔVΔU) at days 0 and 91. The CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response to SIVgag or RhCMV-IE was monitored by flow cytometric analysis of ICCS for CD69, TNFα and IFNγ in PBMC. The percentage of the responding, specific T cells within the overall memory subset is shown for each time point. At day 154 and again on day 224, the same cohort was inoculated with 107 PFU of ΔUS2-11(gag) (ΔU) and RhCMV-IE and SIVgag-specific T cell responses were monitored bi-weekly. At day 737, the cohort was inoculated with ΔVIHCE(gag) (ΔV) and the T cell response was monitored as before. At day 989 the cohort was inoculated with ΔRh186-8(retanef) (ΔR). Besides SIVgag, a T cell response to SIVrev/nef /tat was detected by ICCS in all four animals (black lines) using corresponding overlapping peptides. Inset: A separate cohort of four animals was infected with wildtype RhCMV(gag) and the RhCMV-IE and SIVgag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response was monitored as described above at the indicated time points for 133 days. (B) The CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response to SIVgag in BAL was measured in parallel to the PBMC T cell responses shown in (A). (C) RhCMV secreted in the urine collected from the cohort infected with RhCMV(gag), or deletion viruses ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) or ΔUS2-11(gag), labeled ΔCMV. Virus was isolated at the indicated days by co-culture with telomerized rhesus fibroblasts (TRFs) and cell lysates were probed for expression of SIVgag by immunoblot. (D) Expression of RhCMV-IE2, SIVgag and SIVretanef by virus secreted in urine collected at the indicated days. Note that all animals were IE2-positive at the onset of the experiment confirming their RhCMV-positive T cell status (table S1D).

Our results show that genes within the US2-11 region are essential for super-infection, which is consistent with the known function of US2, US3, US6, and US11 as inhibitors of MHC-I antigen presentation. There are, however, three genes of unknown function (Rh186-Rh188) encoded between US6 and US11. Rh186 and Rh187 are most closely related to the HCMV glycoproteins US8 and US10, respectively (13), whereas Rh188 is an uncharacterized RhCMV-specific ORF. Although binding of HCMV-US8 and US10 to MHC-I has been reported it is unclear whether this affects antigen presentation since MHC-I surface expression is not reduced by US8 or US10 from either HCMV or RhCMV (13, 15, 16). To determine whether Rh186, Rh187 or Rh188 are required for super-infection we generated deletion virus ΔRh186-8. To enable us to monitor super-infection by this recombinant in the same cohort of animals that had already been re-infected with ΔVIHCE(gag), we applied a distinct immunological marker, SIVretanef, a fusion-protein consisting of SIV rev, tat and nef (3). ΔRh186-8(retanef) is deleted for Rh186-188 and contains the Retanef expression cassette between the ORFs Rh213 and Rh214 (fig. S1). We inoculated the same cohort with ΔRh186-8(retanef) and monitored the T cell response to this fusion protein as well as to RhCMV-IE and SIVgag using corresponding peptides. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, all four RM developed a SIVretanef-specific T cell response within two weeks post-challenge indicating successful super-infection. Moreover, virus expressing SIVretanef was shed in the secretions of infected animals together with SIVgag-expressing ΔVIHCE(gag) (Fig. 3D). We thus conclude that the Rh186-8 region is dispensable for super-infection.

Together, our results suggested that RhCMV was unable to super-infect in the absence of the homologues of US2, US3, US6 and US11, because the virus was no longer able to avoid elimination by CTL. To further examine this hypothesis, a new group of RhCMV+ RMs (table S1D) was depleted for CD8+ lymphocytes by treatment with the humanized anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody cM-T807 prior to super-infection with ΔUS2-11(gag) or ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag). Flow cytometric analysis of total CD8+ T cells revealed that depletion was extensive, but transient, with detectable CD8 +T cell recovery beginning on day 21 after challenge (Fig. 4A, B). After challenge with ΔUS2-11(gag) or ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag), SIVgag-specific CD4+ T cell responses were recorded as early as day 7 post-challenge showing the ability of the deletion viruses to super-infect these animals (Fig. 4C). Moreover, SIVgag-specific CD8+ T cells were observed within the rebounding CD8+ T cells in blood and BAL at day 21 in two RM and at day 28 in a third; in the fourth RM, such responses were only observed in BAL after day 56. From these data we conclude that CD8+ lymphocytes, most likely CD8+ T cells, were essential for preventing super-infection by ΔUS2-11 virus, strongly indicating that the MHC-I inhibitory function of these molecules is necessary for super-infection of the CMV-positive host. Importantly, CMV-specific CD8+ T cells were unable to eliminate RhCMV lacking MHC-I inhibitors once persistent infection had been established (Fig. 4D), providing additional evidence that persistent infection is insensitive to CD8+ T cell immunity, even when the ability of the virus to prevent MHC-I presentation is compromised.

Fig. 4.

CD8+ T cells protect rhesus macaques from infection by RhCMV lacking MHC-I inhibitors. (A) Four CMV-positive RM were treated at the indicated days with the anti-CD8 antibody CM-T807 prior to and after inoculation with 107 PFU of ΔVIHCEΔUS2-11(gag) (2 animals, black line) or ΔUS2-11(gag) (two animals, red line). The absolute counts of CD8+ T cells in the blood of each animal are shown over time. (B) The presence of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in PBMC of one representative animal is shown for the indicated days. (C) SIVgag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in PBMC and BAL of CD8+ T cell-depleted animals were monitored by ICCS for CD69, TNFα and IFNγ and are shown as a percentage of total memory CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Note the delayed appearance of SIVgag-specific CD8+ T cells. (D) Expression of SIVgag or IE2 by RhCMV secreted in the urine of animals infected upon CD8+ depletion.

Our data imply that T cell evasion is not required for establishment of primary CMV infection or once the sites of persistence (e.g. kidney and salivary gland epithelial cells) have been occupied, but rather it is essential to enable CMV to reach these sites of persistence from the peripheral site of inoculation in the CMV-immune host. One possible scenario is that viral infection of circulating cells, e.g. monocytes, can only succeed if the virus prevents elimination of these cells by virus-specific CTLs. More work, however, will be required to identify the cell type supporting super-infection.

Although the biochemical and cell biological functions of US2, US3, US6 and US11 have been studied extensively (17), their role in viral pathogenesis had remained enigmatic. Analogous gene functions in murine CMV had been similarly found to be dispensable for both primary and persistent infection (9), although reduced viral titers have been reported for MCMV deleted for these genes (18). Thus, the reason why all known CMVs dedicate multiple gene products to MHC-I downregulation had remained elusive. Our current results now identify a critical role for these immunomodulators to enable super-infection of the CMV-positive host. Furthermore, these results suggest that the ability to super-infect is an evolutionary conserved function among CMVs, and therefore might play an important role in the biology of these viruses. Super-infection could promote the maintenance of genetic diversity of CMV strains in a highly infected host population, which could provide an evolutionary advantage. However, there is another possibility. CMV is a large virus with thousands of potential T cell epitopes, and therefore a high potential for CD8+ T cell cross-reactivity (19). Indeed, in a study of pan-proteome HCMV T cell responses, 40% of HCMV seronegative subsets manifested one or more cross-reactive CD8+ T cell responses to HCMV-encoded epitopes (5). As CMV recognition by cytotoxic T cells appears to effectively block primary CMV infection, individuals with cross-reactive CD8+ T cell immunity might be resistant to CMV. Thus, US2-11 function may be necessary to evade such responses and establish infection in this large population of individuals that might otherwise be CMV-resistant.

Our results also may explain why, so far, it has not been possible to develop a vaccine that efficiently protects humans from HCMV infection. Although antibody-mediated mucosal immunity might reduce the rate of super-infection (7, 20), once this layer of defense is breached, CMV-specific CTLs seem to be unable to prevent viral dissemination, due to MHC-I downregulation by US2-11. Thus, although CMV-vaccines might be able to limit CMV-viremia and associated morbidity, this MHC-I interference renders it unlikely that sterilizing protection against CMV infection is an achievable goal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to P. Barry for providing the RhCMV-GFP and RhCMV-BAC and M. Messerle for plasmid ori6k-F5. The NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource Program provided the CD8α-specific antibody cM-T807 used in this work (contracts AI040101 and RR016001), which was originally obtained from Centocor, Inc.. We thank A. Townsend for help with the graphics. We thank D. Drummond, L. Coyne-Johnson, M. Spooner Lewis, C. Hughes, N. Whizin, M.Giday, J. Clock, J. Cook, J. Edgar, J. Dewane and A. Legasse for technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (RO1 AI059457 to K.F. and RO1 AI060392 to L.P.), the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (to L.P.) the National Center for Research Resources (RR016025 and RR18107 to M.K.A; RR00163 supporting the Oregon National Primate Research Center), the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards T32 AI007472 (to C.J.P.) and T32 HL007781 (to R.R.), the OHSU Tartar Trust fellowship (to C.J.P.) and the Achievement Reward for College Scientists (to R.R.). The CMV vector technology has been patented by OHSU (US2008/0199493A1) with Louis Picker, Jay A.Nelson and Michale Jarvis as co-inventors. This patent has been licensed to the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.. The comparative genome sequencing data shown in fig. S5 were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE20308).

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.”

References and Notes

- 1.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorman S, et al. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1123. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen SG, et al. Nat Med. 2009;15:293. doi: 10.1038/nm.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer-König U, Ebert K, Schrage B, Pollak S, Hufert FT. Lancet. 1998;352:1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sylwester AW, et al. J Exp Med. 2005;202:673. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler SP, et al. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:26. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plotkin SA, Starr SE, Friedman HM, Gonczol E, Weibel RE. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:860. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walter EA, et al. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto AK, Hill AB. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:434. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Wal FJ, Kikkert M, Wiertz E. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;269:37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59421-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z, Winkler M, Biegalke B. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009 Mar;41:503. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt EW, Gupta SS, Lehner PJ. Embo J. 2001;20:387. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pande NT, Powers C, Ahn K, Früh K. J Virol. 2005;79:5786. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5786-5798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powers CJ, Früh K. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tirabassi RS, Ploegh HL. J Virol. 2002 Jul;76:6832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6832-6835.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furman MH, Dey N, Tortorella D, Ploegh HL. J Virol. 2002;76:11753. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11753-11756.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers C, DeFilippis V, Malouli D, Früh K. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:333. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krmpotic A, et al. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1285. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selin LK, et al. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:164. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pass RF, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.