Abstract

Trifluoromethyl-substituted superelectrophiles were generated in superacid (CF3SO3H) and their chemistry was examined. The strong electron withdrawing properties of the trifluoromethyl group are found to enhance the electrophilic character at cationic sites in superelectrophiles. This leads to greater positive charge-delocalization in the superelectrophiles. These effects are manifested by the superelectrophiles showing unusual chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity in reactions.

The trifluoromethyl (-CF3) group is one of the most powerful electron withdrawing groups in structural organic chemistry.1 This property is often manifested by increasing reactivities of adjacent acidic or electrophilic functional groups. The -CF3 group primarily activates electrophilic sites by inductive electron withdrawing effects. Similar electrophilic activation has been observed from cationic functional groups and structures.2 Depending on the cationic group, very strong electron withdrawing effects may occur via inductive, resonance, or other electrostatic effects. Multiply charged cationic electrophiles (i.e., dications or trications) have even been described as superelectrophiles, based on their high electrophilic reactivities.3 In this communication, we report the results of our studies on trifluoromethyl-substituted superelectrophiles. Despite their high electrophilic reactivities, these species exhibit well-defined chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivities in their reactions.

Our initial experiments examined the superacid-promoted reaction of 2-(trifluoroacetyl)pyridine (1) with benzene (eq 1). In contrast to 2-acetylpyridine (3; eq 2), which gives the condensation product (4),4 compound 1 gives an intermediate alcohol product (2). Rather than enhancing the electrophilic

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

condensation with benzene, the -CF3 group slows the final substitution step and the hydroxy group is relatively stable in the superacid. For this type of condensation (the hydroxyalkylation reaction5), selective formation of the intermediate alcohol is rare. Other N-heterocyclic systems (Table 1, entries 1-3) were studied and the heterocyclic alcohols (13-15) were obtained as the only major products in reactions at 25°C.

Table 1.

Products and yields for reactions of trifluoromethyl substrates with CF3SO3H and C6H6.

Reaction done at 25°C;

reaction done at 60°C.

We propose that the -CF3 derivatives show this chemoselectivity due to the increased reactivities of the intermediate carbenium-based superelectrophiles, leading to strengthening of carbon-oxygen bond. In the case of 2-(trifluoroacetyl)pyridine (1), reaction with benzene leads to formation of the pyridinium-oxonium dication 22a (eq 3). Loss of water from 22a is inhibited, because cleavage of the carbon-oxygen bond requires separation of a relatively strong

|

(3) |

nucleophile (H2O) from a very powerful electrophile (23a). This effect is similar to the well-known kinetic stabilities of uncharged, -CF3 substituted systems.6 Likewise, several reports have described chemistry with small, highly charged ions and their tendencies to retain good leaving groups (i.e. halogens or protonated hydroxy groups), even in superacidic media.7 The effect of the -CF3 group in 22a is apparent, as the closely related system (from 2-acetylpyridine) 22b cleaves rapidly at 25°C to the carbocationic superelectrophile (23b). Thus, the observed chemoselectivity is the result of a strengthening of the carbon-oxygen bond by the −CF3 group in the pyridinium-oxonium dication.

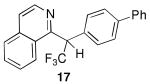

With heating in superacid, the N-heterocyclic alcohols do lead to formation of a condensation product with benzene, however it is not the expected product from the hydroxyalkylation reaction. Instead, regioselective functionalization at a remote site is observed (Table 1, entries 4-6). Reactions of alcohols 2, 8-9 in CF3SO3H and C6H6 at 60°C lead to compounds 16-18 (respectively) as the only major products.8 These conversions can be contrasted with the hydroxyalkylation product observed from 2-acetylpyridine, where nucleophilic attack by benzene occurs at the site of alcohol ionization (i.e. 22b) and the gem-diphenyl group is produced (eq 2). This unusual regioselectivity is clearly the result of the inductive effects from the −CF3 group. In compound 2, ionization of the alcohol group leads to 23a and delocalization of the π-electrons lead to positive charge accumulating in the 4-position of the phenyl group (eq 4).

|

(4) |

Nucleophilic attack by benzene gives 24 and proton transfer steps give the final product 16. The present results suggest that −CF3 substituents can increase the importance of charge-charge repulsive effects in superelectrophiles.

Besides effecting chemoselectivity and regioselectivity, we have found evidence that −CF3 substituents may also influence the stereoselectivity in superelectrophilic condensation reactions. Trifluoromethyl-substituted 1,3-diketones (10-12) were reacted with benzene in superacidic CF3SO3H and substituted indanes (19-21) were formed stereoselectively in excellent yields (Table 1, entries 7-9). For example, compound 25a gives product 26 by reaction with three molecules of benzene (eq 5). NMR spectroscopy and

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

X-ray crystallography indicates exclusive formation of the syn stereoisomer (26). The influence of the −CF3 groups is clearly significant, as 2,4-pentanedione (25b) in CF3SO3H does not react with benzene.9 The preference for syn stereochemistry is also thought to be a consequence of the −CF3 group(s). Condensation at one of the carbonyl centers produces a gem-diphenyl group, while the other carbonyl gives the intermediate carbocation (i.e., 27 eq 6). With cyclization of the carbocation, the indane ring system is formed. The observed stereochemistry suggests conformer 27 is strongly preferred and dictates the stereochemical outcome of the reaction (cyclization into either of the adjacent phenyl rings will give the observed syn stereochemistry). Cationic π-stacking is known for its ability to produce ordered structures and to even influence stereochemistry.10 Evidently, the −CF3 group leads to significant charge delocalization into the phenyl group and the resulting cationic π-stacking stabilizes conformer 27.

In conclusion, the results indicate that −CF3 groups (and presumably other perfluoroalkyl groups) can have profound effects on the chemistry of superelectrophiles. The strong electron withdrawing properties lead to increased charge delocalization and they greatly enhance the electrophilic reactivities of these ions. Despite the high electrophilic reactivities, these systems have shown interesting chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivities in their conversions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the National Science Foundation (CHE-0749907) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH, GM085736-01A1).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, characterization data for new compounds, and crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Olah GA, Chambers RD, Prakash GKS. Synthetic Flourine Chemistry. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]; b Schlosser M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1496. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980619)37:11<1496::AID-ANIE1496>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Olah GA, Prakash GKS, Molnar A, Sommer J. Superacid Chemistry. 2nd. Wiley & Sons; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klumpp DA, Activation of Electrophilic Sites by Adjacent Cationic Groups . Recent Developments in Carbocation and Onium Ion Chemistry. In: Laali K, editor. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 395. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2007. pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olah GA, Klumpp DA. Superelectrophiles and Their Chemistry. Wiley & Sons; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klumpp DA, Garza G, Sanchez GV, Lau S, DeLeon S. J Org Chem. 2000;65:8997. doi: 10.1021/jo001035k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash GKS, Panja C, Shakhmin A, Shah E, Mathew T, Olah GA. J Org Chem. 2009;74:8659. doi: 10.1021/jo901668j. and reference cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Allen AD, Kanagasabapathy VM, Tidwell TT. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:3470. [Google Scholar]; b Allen AD, Fujio M, Mohammed N, Tidwell TT, Tsuji Y. J Org Chem. 1997;62:246. doi: 10.1021/jo961387k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Creary X. Chem Rev. 1991;91:1625. [Google Scholar]; d Begue JP, Benayoud F, Bonnet-Delpon D, Allen AD, Cox RA, Tidwell TT. Gazz Chim Ital. 1995;125:399. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Olah GA, Prakash GKS, Shih JG, Krishnamurthy VV, Mateescu GD, Liang G, Sipos G, Buss V, Gund TM, Schleyer PvR. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:2764. [Google Scholar]; b Prakash GKS, Krishnamurthy VV, Arvanaghi M, Olah GA. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3985. [Google Scholar]; c Olah GA, Comisarow MB. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3313. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For somewhat related examples of biphenyl group formation, see: Ohwada T, Okabe K, Ohta T, Shudo K. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:7539.Shudo K, Ohta T, Ohwada T. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:645.Nakamura S, Sugimoto H, Ohwada T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1724. doi: 10.1021/ja067682w.

- 9.The exact role of dicationic superelectrophiles in the condensation of 25a has not been determined, however by analogy to other diketones (reference 3, pp 140-142), the reaction may be initiated by protonation of both carbonyl groups. The final cyclization step occurs via the monocationic electrophile 27. Substrates 11 and 12 react via distonic superelectrophiles.

- 10.a Cakir SP, Stokes S, Sygula A, Mead KT. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7529. doi: 10.1021/jo901436u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ma JC, Dougherty DA. Chem Rev. 1997;97:1303. doi: 10.1021/cr9603744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.