Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cumulative incidence of self-reported influenza vaccination (“vaccination coverage”) and investigate predictors in HIV-infected women.

Methods

In an ongoing cohort study of HIV-infected women in five US cities, data from two influenza seasons (2006-07 n=1,209 and 2007-08 n=1,161) were used to estimate crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals ([,]) from Poisson regression with robust variance models using generalized estimating equations (GEE).

Results

In our study, 55% and 57% of HIV-infected women reported vaccination during the 2006-07 and 2007-08 seasons, respectively. Using data from both seasons, older age, non-smoking status, CD4 T-lymphocyte (CD4) count ≥200 cells/mm3, and reporting at least one recent healthcare visit was associated with increased vaccination coverage. In the 2007-08 season, a belief in the protection of the vaccine (aPR=1.38 [1.18, 1.61]) and influenza vaccination in the previous season (aPR=1.66 [1.44, 1.91]) most strongly predicted vaccination status.

Conclusion

Interventions to reach unvaccinated HIV-infected women should focus on changing beliefs about the effectiveness of influenza vaccination and target younger women, current smokers, those without recent healthcare visits, or a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, highly active antiretroviral therapy, influenza vaccine, vaccine coverage, multi-center study, cohort study, United States, adult, female

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), seasonal influenza infection causes an estimated 226,000 hospitalizations and 36,000 deaths annually (Thompson et al., 2003, Thompson et al., 2004). Case studies and series have described prolonged illness and associated complications of influenza in HIV-infected individuals (Evans and Kline, 1995, Radwan et al., 2000, Safrin et al., 1990, Thurn and Henry, 1989). Further, three retrospective cohort studies have shown a substantial increase in influenza-associated morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected individuals (Lin and Nichol, 2003, Neuzil et al., 1999, Neuzil et al., 2003). Since 1988, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended annual influenza vaccination for HIV-infected individuals in the US (Immunization Practices Advisory Committee, 1988). HIV-infected individuals were also recommended to receive the monovalent 2009 H1N1 vaccine and were indicated for antiviral treatment in cases of likely H1N1 infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Among HIV-infected individuals, the influenza vaccine reduces symptomatic influenza illness by 66% (Anema et al., 2008).

A report of annual influenza vaccination coverage in HIV-infected individuals from 1990-2002 found <50% compliance with the ACIP recommendation (Gallagher et al, 2007). Few studies have had the ability to examine medical and social factors with vaccination in the HIV population. The Adult and Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease (ASD) study relied on medical records and showed the combination of healthcare, HIV markers, and use of therapy were associated with influenza vaccination (Gallagher et al., 2007, Sorvillo and Nahlen, 1995, Wortley and Farizo, 1994). They did not have the opportunity to examine factors such as vaccination and illness beliefs that have been strongly associated with vaccine receipt among the elderly (Chi and Neuzil, 2004, Hornby et al., 2005, Janz and Becker, 1984, Lau et al., 2006, Lau et al., 2007, Nexøe et al., 1999).

The objectives of this study were two-fold: 1) to estimate the cumulative incidence of self-reported influenza vaccination (“vaccination coverage”) in the 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons in the largest cohort study of HIV-infected women in the US: the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS); and 2) to identified predictors of reported influenza vaccination.

METHODS

Study population

The WIHS enrolled a total of 3,766 women, of whom 2,902 were HIV-infected, in two recruitment waves (1994-5 and 2000-2001) at six clinical centers to study the natural history of HIV infection and has been described elsewhere (Bacon et al., 2005, Barkan et al., 1998). All participants were ≥13 years of age at study entry, reported high HIV transmission risk and gave informed consent. Although the response rate to recruitment is unknown, the demographics of the WIHS cohort reflect the characteristics of HIV-infected women in the general US population (Barkan et al., 1998). Participants completed study visits every six months that include detailed interviews, a physical examination, and collection of blood and other specimens. Study protocols and consent forms have been approved by institutional review boards at each study site.

Our nested influenza study investigated the 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons. HIV-infected WIHS participants were eligible if they completed at least one study visit between April 2006-September of 2007 or 2008, i.e. the study periods for the 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons, respectively. Women were included in our study if they completed three consecutive study visits and had complete vaccination reports during one or both of those influenza seasons; thus a participant could contribute information to one or both influenza seasons. Participants who seroconverted or transferred study sites during the 2007-07 or 2007-08 season were excluded from the analysis of that season.

Outcome: Influenza vaccination

Self-reports of the occurrence and date of influenza vaccination were collected via the interviewer-administered questionnaire. If a woman reported an influenza vaccination occurring between October 1 and April 30 she was categorized as vaccinated. In a review of 159 Chicago participants, 138 (87%) of the self-reported influenza vaccinations were confirmed using outpatient medical records (A. French, personal communication).

Predictors of influenza vaccination

Predictors were measured prior to the start of each influenza season (i.e. April – September). Mode of transmission, year of birth, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income, country of birth, drug and alcohol use in the prior six months, cigarette smoking status, medical insurance status, reporting at least one visit with a healthcare professional in the prior 6 months and pneumonia in the prior six months (excluding Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia) were self-reported. Subjects were classified as having depressive symptoms if they had a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) score ≥23 for injection drug users and ≥16 for all others (Golub et al., 2004). Participants who reported receiving vaccination to prevent any of the following conditions were classified as having received another vaccination in the prior six months: hepatitis A, hepatitis B, Pneumococcal disease including pneumonia, varicella, tetanus or the human papillomavirus vaccine.

We used ACIP recommendations to categorize the following conditions as clinical indications for influenza vaccination: pregnancy (tested at each visit), diabetes mellitus (current or prior measure of fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL measured at two consecutive study visits, or self-reported diabetes mellitus, or use of anti-diabetic medication), chronic kidney disease (estimated MDRD glomerular filtration rate <60mL/min/1.73m2), and self-reported asthma, congestive heart failure, or immunosuppression due to chemotherapy (Fiore, et al., 2009). Information regarding chronic lung disease was not available.

Self-reported clinical AIDS used the 1993 CDC surveillance definition, excluding CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1992). CD4 count was measured using standard flow cytometry techniques and dichotomized at 200 cells/mm3. Plasma HIV viral loads were measured using the isothermal nucleic acid sequence-based amplification method (NucliSens, BioMerieux, Boxtel, NC). Current therapy use was self-reported using a standard definition consistent with the US DHHS Guidelines (Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV infection from the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1998). Medication photo-ID cards and the option to bring medications to study visits assist in recall and accurate identification of self-reported HIV treatment.

Beliefs about influenza illness and vaccination were only available for the 2007-08 season. Belief predictors were measured using questions modified from vaccination coverage studies in the elderly that utilized the Health Belief Model and a 5-category Likert scale (Chi and Neuzil, 2004, Nexøe et al., 1999, Rosenstock, 1974, Schwartz et al., 2006) (see Supplement).

Statistical Analyses

Data were combined for the two influenza seasons and examined with person-seasons used as the denominator of vaccination coverage. Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR and aPR, respectively), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using Poisson approximations to log-binomial regression models with robust variance and the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach to adjust for within-individual correlations from women contributing information for both seasons (Skov et al., 1998, Spiegelman and Hertzmark, 2005, Zeger et al., 1988, Zocchetti et al., 1997). All demographic and clinical characteristics previously shown to be associated with influenza vaccination were included in multivariate models (Gallagher et al., 2007). We also included non-clinical predictors with scientific plausibility of an association with influenza vaccination, many of which have not been previously examined in HIV-infected individuals. We created parsimonious models with statistically significant variables and compared the point estimates to those from saturated models (that included all predictors examined) to determine estimate stability.

Data regarding influenza vaccination and illness beliefs and vaccination in the previous influenza season were only collected during the 2007-08 season and examined separately using similar methods. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (Carey, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of n=1,462 HIV-infected women completed at least one study visit from April 2006-September 2007 or April 2007-September 2008. Of these eligible women, n=1,293 (88%) met our inclusionary and exclusionary criteria. Compared to women who contributed data to one or both seasons, women who did not meet our eligibility criteria in either season (n=169) were more likely to be non-Hispanic White or of another race/ethnic group (31% vs.15%, p<0.01), had attained a greater level of education (education after high school: 46% vs. 31%, p<0.01), annual household income (income ≥$36,000: 37% vs. 14%, p<0.01), and were more likely to have private medical insurance (34% vs. 17%, p=<0.01). Excluded women were less likely to report cigarette smoking (33% vs. 41%, p=0.05). Excluded and included women were similar by HIV characteristics. N=1,077 women contributed to both seasons, n=132 and n=84 women contributed solely to the 2006-07 and 2007-08 seasons, respectively, for a total of n=2,370 person-seasons. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of HIV-infected participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) at enrollmenta, 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons, United States

| Characteristics | Participants n= 1,293 n %b |

Number of person- seasons of observationc n=2,370 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <30 years | 73 6 | 118 |

| 30-<40 years | 372 29 | 638 |

| 40-<50 years | 544 42 | 1,017 |

| ≥50 years | 304 24 | 597 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 740 57 | 1,357 |

| Hispanic | 362 28 | 667 |

| Non-Hispanic White & other | 191 15 | 346 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| < High school | 507 39 | 936 |

| High school diploma | 380 29 | 698 |

| More than high school | 404 31 | 764 |

| Annual household income | ||

| ≤$12,000 | 594 46 | 1,148 |

| $12,001-$24,000 | 299 23 | 544 |

| $24,001-$36,000 | 142 11 | 276 |

| ≥$36,000 | 173 13 | 313 |

| Country of birth | ||

| United States & territories | 1,005 78 | 1,837 |

| Other | 287 22 | 531 |

| Center | ||

| Bronx | 245 19 | 454 |

| Brooklyn | 264 20 | 490 |

| Washington, D.C. | 187 14 | 334 |

| Los Angeles | 234 18 | 426 |

| San Francisco | 180 14 | 333 |

| Chicago | 183 14 | 333 |

| Mode of HIV transmission | ||

| Intravenous drug use | 298 23 | 540 |

| Heterosexual contact | 542 42 | 997 |

| Transfusion | 23 2 | 44 |

| None identified | 422 33 | 774 |

| Clinical AIDSd | 521 40 | 962 |

| CD4 T-lymphocyte count | ||

| ≥200 cells/mm3 | 1,094 85 | 2,031 |

| <200 cells/mm3 | 194 15 | 329 |

| Taking HAART | 837 65 | 1,560 |

Abbreviations: AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency virus; HAART: highly-active antiretroviral therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

Participants could contribute independent information to one or both influenza seasons examined. Enrollment is the first season to which the participant contributes.

Percentages may not add to 100% due to missing data.

Numbers may not total to n=2,370 person-seasons due to missing data.

Clinical AIDS was classified as a prior report of a clinical diagnosis defined by the 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance definition, excluding CD4 count <200 cells/mm3.

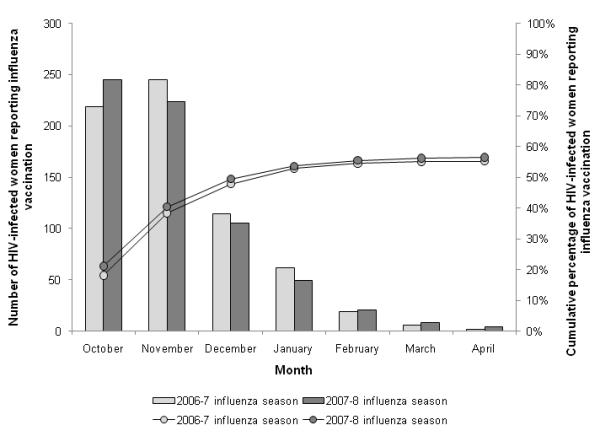

In the 2006-07 (n=1,209) and 2007-08 (n=1,161) seasons, similar percentages of HIV-infected women in our study population reported being vaccinated (55% and 57%, respectively; p-value=0.54), with vaccinations occurring primarily in October and November with slower uptake of vaccine in December, January and February (Figure 1). In the 2006-07 season, n=3 (<1%) women reported receiving the live attenuated intranasal vaccine (LAIV), which is contraindicated in HIV-infected individuals; no women reported LAIV in the 2007-08 season. Of the n=656 women reporting vaccination in the 2007-08 season, n=503 (77%) were asked to report a location of vaccination. The majority of vaccinations were received in a clinical setting (91% or 495/503).

Figure 1.

Month of influenza vaccination reported by HIV-infected women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, 2006-07 (n=1,209) and 2007-08 (n=1,161) influenza seasons, United States

In the analysis of data for both seasons, vaccination coverage increased with increasing age in a dose-response pattern (p-value for trend <0.01) (Table 2). Women attending visits at study sites in San Francisco and Los Angeles, CA, were significantly less likely to report influenza vaccination compared to women attending visits in Bronx, NY. Cigarette smokers were significantly less likely to report being vaccinated than non-smokers. Women who reported at least one healthcare visit in the prior 6 months were more likely to report influenza vaccination. Finally, women with lower CD4 counts were less likely to report influenza vaccination compared to those with a higher CD4 count. Point estimates in the parsimonious model changed <10% points compared to the saturated model estimates, with the exception of the point estimates for age, which attenuated by 14%.

Table 2.

Predictors of influenza vaccination in n=1,293 HIV-infected participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), the 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons, United States

| No. of person- seasons |

Vaccinated women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictorsa | n %b | aPRc | 95% CI | |

| Influenza season | ||||

| 2006-07 | 1209 | 667 55 | REF | |

| 2007-08 | 1161 | 656 57 | 1.02 | 0.96 , 1.09 |

| Age | ||||

| <30 years | 118 | 49 42 | REF | |

| 30-<40 years | 638 | 336 53 | 1.39 | 1.05 , 2.04 |

| 40-<50 years | 1017 | 579 57 | 1.48 | 1.13 , 1.96 |

| ≥50 years | 597 | 359 60 | 1.54 | 1.16 , 1.84 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1357 | 734 54 | REF | |

| Hispanic | 667 | 400 60 | 1.07 | 0.89 , 1.16 |

| Non-Hispanic White & other | 346 | 189 55 | 1.01 | 0.96 , 1.19 |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 936 | 520 56 | REF | |

| High school diploma | 698 | 392 56 | 1.02 | 0.92 , 1.14 |

| More than high school | 764 | 410 54 | 1.02 | 0.91 , 1.14 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≤$12,000 | 1148 | 627 55 | REF | |

| $12,001-$24,000 | 544 | 327 60 | 1.07 | 0.98 , 1.17 |

| $24,001-$36,000 | 276 | 152 55 | 0.95 | 0.83 , 1.08 |

| ≥$36,000 | 313 | 174 56 | 0.97 | 0.84 , 1.12 |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| United States & territories | 1837 | 1009 55 | REF | |

| Other | 531 | 314 59 | 1.05 | 0.92 , 1.20 |

| Center | ||||

| Bronx | 454 | 277 61 | REF | |

| Brooklyn | 490 | 289 59 | 1.04 | 0.91 , 1.19 |

| Washington, D.C. | 334 | 178 53 | 0.92 | 0.79 , 1.07 |

| Los Angeles | 426 | 227 53 | 0.83 | 0.71 , 0.97 |

| San Francisco | 333 | 163 49 | 0.82 | 0.69 , 0.96 |

| Chicago | 333 | 189 57 | 1.01 | 0.88 , 1.17 |

| Depressive Symptomsd | ||||

| No | 920 | 504 55 | REF | |

| Yes | 1428 | 812 57 | 1.01 | 0.93 , 1.10 |

| Drug use in last 6 monthse | ||||

| No | 1954 | 1115 57 | REF | |

| Yes | 416 | 208 50 | 0.95 | 0.83 , 1.07 |

| Alcohol use in prior 6 months | ||||

| Abstainer / Light (<3 drinks/week) | 2112 | 1205 57 | REF | |

| Moderate / Heavy (≥3 drinks/week) | 248 | 117 47 | 0.90 | 0.77 , 1.05 |

| Current cigarette smoker | ||||

| No | 1407 | 825 59 | REF | |

| Yes | 953 | 497 52 | 0.90 | 0.82 , 1.00 |

| Received another vaccination in the prior 6 monthsf | ||||

| No | 1983 | 1088 55 | REF | |

| Yes | 337 | 202 60 | 1.07 | 0.97 , 1.18 |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Publicg | 1593 | 883 55 | REF | |

| Private or other | 408 | 236 58 | 1.05 | 0.92 , 1.21 |

| None | 359 | 201 56 | 1.06 | 0.93 , 1.20 |

| At least one healthcare visit in the prior 6 months | ||||

| No | 159 | 59 37 | REF | |

| Yes | 2141 | 1227 57 | 1.46 | 1.13 , 1.88 |

| One or more indications for influenza vaccinationh | ||||

| No | 1229 | 674 55 | REF | |

| Yes | 1141 | 649 57 | 1.00 | 0.92 , 1.09 |

| Pneumonia in the prior 6 monthsi | ||||

| No | 2257 | 1254 56 | REF | |

| Yes | 113 | 69 61 | 1.13 | 0.96 , 1.34 |

| Mode of HIV transmission | ||||

| Intravenous drug use | 540 | 307 57 | REF | |

| Heterosexual contact | 997 | 585 59 | 0.97 | 0.87 , 1.09 |

| Transfusion | 44 | 28 64 | 1.01 | 0.76 , 1.35 |

| None identified | 774 | 399 52 | 0.87 | 0.76 , 1.00 |

| Clinical AIDS diagnosisj | ||||

| No | 1408 | 0 | REF | |

| Yes | 962 | 538 56 | 0.98 | 0.90 , 1.07 |

| CD4+ T-lymphocyte count | ||||

| ≥200 cells/mm3 | 2031 | 1163 57 | REF | |

| <200 cells/mm3 | 329 | 154 47 | 0.86 | 0.97 , 0.99 |

| HIV viral load | ||||

| ≤80 copies/mL | 1282 | 747 58 | REF | |

| 81-9,999 copies/mL | 657 | 345 53 | 1.03 | 0.94 , 1.14 |

| ≥10,000 copies/mL | 411 | 217 53 | 1.07 | 0.94 , 1.22 |

| Taking HAART | ||||

| No | 810 | 407 50 | REF | |

| Yes | 1560 | 916 59 | 1.09 | 0.99 , 1.21 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency virus; aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Predictors were measured prior to the influenza season (between April 1 and September 30).

Denominator is person-seasons.

Adjusted for all the predictors in the table.

Depressive symptoms is defined as a CESD score ≥16 for women not reporting injection drug use and ≥23 for women reporting injection drug use.

Drug use includes reporting injection or non-injection use of any of the following: marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroine, methadone, amphetamines, methamphetamine, non-prescription methadone or narcotics.

Vaccination to prevent the following conditions were classified as having received another vaccination in the prior six months: hepatitis A, hepatitis B, Pneumococcal disease including pneumonia, varicella, tetanus or the human papillomavirus vaccine

Public medical insurance includes Medicaid/Medi-CAL (California only), Medicare and Veteran’s medical insurance.

Indicated if currently pregnant, or have any of the following: diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, asthma or received chemotherapy.

Excludes Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia.

Clinical AIDS was classified as a prior report of clinical diagnosis defined by the 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance definition, excluding CD4 count <200 cells/mm3.

Influenza illness and vaccination belief predictors in the 2007-08 influenza season

Beliefs about influenza illness and vaccination strongly predicted reported influenza vaccination (Table 3). In the crude analysis, all influenza illness and vaccination beliefs statistically significantly predicted reported influenza vaccination, except a dislike for needle sticks in a health-care setting and knowledge of where to access an influenza vaccination free-of-charge. Women who agreed with “The flu shot made me sick” were less likely to report vaccination; however the relationship had borderline statistical significance (p=0.06).

Table 3.

Influenza vaccination and illness belief predictors, and other significant predictors, of influenza vaccination in n=1,161 HIV-infected participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), 2007-08 influenza season, United States

| No. of person- seasons |

Immunized women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictorsa | n %b | PR | 95% CI | aPRc | 95% CI | |

| At least one healthcare visit in the prior 6 months |

||||||

| No | 77 | 28 36 | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 1023 | 564 55 | 1.60 | 1.17 , 2.18 | 1.34 | 1.00 , 1.79 |

| CD4+ T-lymphocyte count | ||||||

| ≥200 cells/mm3 | 997 | 585 59 | REF | REF | ||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 157 | 67 43 | 0.71 | 0.58 , 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.63 , 0.94 |

| Vaccinated in the previous (2006-07) season |

||||||

| No | 471 | 171 36 | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 690 | 485 70 | 1.86 | 1.63 , 2.13 | 1.66 | 1.44 , 1.91 |

| The flu shot protects me | ||||||

| Disagree | 274 | 115 42 | REF | REF | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 179 | 97 54 | 1.29 | 1.05 , 1.58 | 1.26 | 1.03 , 1.54 |

| Agree | 705 | 442 63 | 1.54 | 1.32 , 1.81 | 1.38 | 1.18 , 1.61 |

| Flu is not a serious disease | ||||||

| Disagree | 860 | 508 59 | REF | REF | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 109 | 55 50 | 0.89 | 0.73 , 1.08 | 0.98 | 0.80 , 1.20 |

| Agree | 189 | 91 48 | 0.78 | 0.66 , 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.72 , 1.01 |

| I am not at high risk for getting the flu | ||||||

| Disagree | 794 | 471 59 | REF | REF | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 129 | 59 46 | 0.79 | 0.65 , 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.74 , 1.10 |

| Agree | 235 | 124 53 | 0.86 | 0.74 , 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.84 , 1.12 |

| The flu shot made me sick | ||||||

| Disagree | 732 | 436 60 | REF | REF | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 103 | 54 52 | 0.85 | 0.68 , 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.80 , 1.22 |

| Agree | 322 | 134 42 | 0.89 | 0.78 , 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.87 , 1.12 |

| I do not like to be study by needles in a healthcare setting |

||||||

| Disagree | 466 | 267 57 | REF | REF | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 175 | 97 55 | 0.96 | 0.82 , 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.86 , 1.16 |

| Agree | 517 | 290 56 | 1.01 | 0.90 , 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.93 , 1.16 |

| I had a discussion with my healthcare professional about the flu shot |

||||||

| No | 823 | 444 54 | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 337 | 211 63 | 1.16 | 1.04 , 1.29 | 1.08 | 0.97 , 1.20 |

| I know where to get a free flu shot | ||||||

| No | 270 | 159 59 | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 890 | 496 56 | 0.97 | 0.86 , 1.10 | 0.94 | 0.84 , 1.06 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency virus; aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PR: crude prevalence ratio.

Predictors were measured prior to the influenza season (between April 1 and September 30).

Denominator is person-seasons.

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, country of birth, center, depressive symptoms (defined as a CESD score ≥16 for women not reporting injection drug use and ≥23 for women reporting jection drug use), drug (including injection or non-injection use of any of the following: marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroin, methadone, amphetamines, methamphetamine, non-prescription methadone or narcotics) and alcohol use in the prior 6 months, current cigarette smoking, receiving any other vaccination in the prior 6 months, medical insurance type (public medical insurance including Medicaid/Medi-CAL (California only), Medicare and Veteran’s medical insurance, private or other), having an indication for influenza vaccination other than HIV (i.e. currently pregnant or have any of the following: diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, asthma or received chemotherapy), pneumonia (excluding Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia) in the prior 6 months, mode of HIV transmission, clinical AIDS diagnosis (classified as a prior report of a clinical diagnosis defined by the 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance definition, excluding CD4 count <200 cells/mm3), HIV viral load, and taking highly-active antiretroviral therapy.

After adjustment for other predictors, women with neutral or affirmative beliefs that influenza vaccination protects them from influenza illness were more likely to report influenza vaccination (Table 3). Also in the adjusted analysis, the strongest predictor of reported influenza vaccination was reporting an influenza vaccination in 2006-07. Among women who contributed to the 2007-08 season (n=1,161), n=485 (42%) reported vaccination in 2007-08 and 2006-07 seasons, n=300 (26%) reported no vaccination in either season, n=171 (15%) reported vaccination in 2007-08 but not 2006-07, and n=205 (18%) reported no vaccination in 2007-08 but previous vaccination in 2006-07. Vaccination coverage was higher among women who had at least one healthcare visit in the prior 6 months, and lower among women with a lower CD4 count. Point estimates in the parsimonious model changed <10% points compared to the saturated model estimates. Estimates were similar in a sensitivity analysis that restricted to women contributing in both seasons (i.e. n=84 women that did not contribute data to the 2006-07 season were excluded).

DISCUSSION

Despite current vaccination guidelines (Fiore et al., 2009), and evidence of benefit from influenza vaccination (Ranieri et al., 2005, Tasker et al., 1999, Yamanaka et al., 2005), 55% and 57% of HIV-infected women reported receiving influenza vaccination during the 2006-07 and 2007-08 influenza seasons, respectively. Our findings indicate beliefs about influenza illness and vaccination, access to healthcare, and CD4 count are important predictors of reported influenza vaccination.

During the 2007-08 influenza season, 30% and 50% of 19-to-49-year-olds and 50-to-64-year-olds who were recommended for vaccination self-reported influenza vaccination, respectively (National Health Interview Survey, 2008). Our estimates of vaccination coverage in HIV-infected women are greater than these estimates, however they are congruent with a previous report of an increasing trend in influenza vaccination among HIV-infected adults (21% to 42% from 1995 to 2002, p-value for trend <0.01) (Gallagher, 2007); further, the demographics of the WIHS cohort reflect the characteristics of HIV-infected women in the general US population (Barkan et al., 1998). HIV-infected individuals may have a higher vaccination coverage compared to individuals of similar age who are recommended to receive the annual vaccine due to contact with infectious disease physicians, as our studies and previous studies have shown health care visits are an important predictor of vaccination (Gallagher et al, 2007, Wortley and Farizo,1994, Sorvillo and Nahlen, 1995). Further, infectious disease physicians may have greater access to vaccine and/or a greater focus on preventing infections in those who have deficient immune systems compared to other specialists caring for individuals who are recommended to receive influenza vaccine. In addition, compared to other groups recommended for vaccination, HIV-infected individuals maybe more conscientious about vaccination to prevent illness due to their immune deficiency. Another source of bias resulting in overestimation of vaccine coverage in our population may be the high sensitivity and low specificity of self-reported influenza vaccination, as seen in the elderly (Zimmerman et al., 2003). Sensitivity and specificity could not be assessed because women who did not report influenza vaccination were not included in the medical record review. Conversely, the WIHS participants who did not meet our study criteria and were excluded had a higher socioeconomic position were less likely to report cigarette smoking than those who were included in our study. If the HIV-infected non-smoking women of higher socioeconomic position have higher influenza vaccination coverage, our results are underestimated. Despite these potential biases, our estimates suggest the attainability of the Health People 2010 goal of 60%, but also substantial non-compliance with ACIP recommendations (Fiore et al., 2009).

Our combined data from two influenza seasons suggest influenza vaccination promotion efforts to HIV-infected women should target younger, current smokers with lower CD4 counts and those who have not have recent access to healthcare. Vaccination coverage increased in a dose-response pattern with increasing age, as seen in other studies (Gallagher et al., 2007, Wortley and Farizo, 1994). Reported influenza vaccination was lower among cigarette smokers, a novel predictor among HIV-infected individuals. Previous studies have reported frequency of healthcare visits during the influenza season as a strong predictor of influenza vaccination (Gallagher et al, 2007, Wortley and Farizo,1994, Sorvillo and Nahlen, 1995). This variable was not available here, but having a recent healthcare visit was a strong predictor of vaccination status. Although the mechanisms of these relationships were not investigated, these predictors can inform interventions. Data from both seasons also showed reduced vaccination coverage in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA. Self-reported influenza vaccination coverage during the 2005-06 season among adults aged 18-64 who are recommended to receive annual influenza vaccine was lower in California (25%) than the states in which the other WIHS study sites were located (Maryland 28%, Illinois 29%, New York 32%, Washington DC 33%) (Lu et al., 2007). Further research is needed to understand the lower vaccination coverage in California.

Belief in the protection of the vaccine and vaccination in the previous season were strong predictors of influenza vaccination. Interventions that provide education about vaccine effectiveness in HIV-infected individuals may alter beliefs and increase vaccination coverage. Although non-clinical interventions are also needed, healthcare providers clearly play an important role in influenza vaccination.

The strengths of this study include: 1) updated estimates of vaccination coverage among HIV-infected women in two recent influenza seasons; 2) the availability of non-clinical predictors, especially beliefs regarding influenza illness and vaccination; 3) the utility in the identified predictors to describe unvaccinated women and inform interventions. Limitations to this study beyond self-reported influenza vaccination include the inability to infer temporality of belief predictors with vaccination status. One previous study showed women were 11% more likely to receive the influenza vaccine compared to men (Gallagher et al., 2007); generalizability of these findings to HIV-infected men is restricted.

CONCLUSION

Our data supports the attainability of the Health People 2010 goal of 60% influenza vaccination coverage among HIV-infected women; however, there was a large proportion (approximately 44%) who were not vaccinated, demonstrating non-compliance with ACIP recommendations. Interventions to reach unvaccinated HIV-infected women should focus on changing beliefs about the effectiveness of the influenza vaccination and target younger, current smokers, without recent healthcare visits and CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [grant numbers UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590]; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant number UO1-HD-32632]. The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources [UCSF-CTSI grant number UL1 RR024131]. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the Johns Hopkins Training Program in Sexually Transmitted Infections [T32-AI050056] to [KNA].

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington, DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Anema A, Mills E, Montaner J, Bronstein JS, Cooper C. Efficacy of influenza vaccination in HIv-positive patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2008;9:57–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, Gange S, Barranday Y, Holman S, Weber K, Young MA. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, Young M, Greenblatt R, Sacks H, Feldman J. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;41:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Use of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi RC, Neuzil KM. The association of sociodemographic factors and patient attitudes on influenza vaccination rates in older persons. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:113–117. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans KD, Kline MW. Prolonged influenza A infection responsive to rimantadine therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:332–334. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199504000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine AD, Bridges CB, De Guzman AM, Zeller B, Wong SJ, Baker I, Regnery H, Fukuda K. Influenza A among patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Chest. 2001;98:33–37. doi: 10.1086/320747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-8):1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KM, Juhasz M, Harris NS, Teshale EH. Predictors of influenza vaccination in HIV-infected patients in the United States, 1990-2002. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:339–346. doi: 10.1086/519165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub ET, Latka M, Hagan H, Havens JR, Hudson SM, Kapadia F, Campbell JV, Garfein RS, Thomas DL, Strathdee SA. Screening for depressive symptoms among HCV-infected injection drug users: examination of the utility of the CES-D and the Beck Depression Inventory. J Urban Health. 2004;81:278–290.1. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessol NA, Schenider M, Greenblatt RM, Bacon M, Barranday Y, Holman S, Robison E, Williams C, Cohen M, Webber K. Retention of women enrolled in a prospective estudy of human immunodeficiency virus infection: ipace of race, unstable housing, and use of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:563–573. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornby PW, Williams A, Burgess MA, Wang H. Prevalence and determinants of influenza vaccination in Australians aged 40 years and over: A national survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:35–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunization Practices Advisory Committee Recommendations of the immunization practices advisory committee prevention and control of influenza. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon FP, Rimmelzwaan GF, Roos MT, Osterhaus AD, Hamann D, Miedema F, van Dissel JT. Restored humoral immune response to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected adults treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:F217–F223. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199817000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JTF, Yang X, Tsui HY, Kim JH. Prevalence of influenza vaccination and associated factors among comunity-dwelling Hong Kong residents of age 65 or above. Vaccine. 2006;24:5526–5534. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JTF, Kim JH, Choi KC, Tsui HY, Yang X. Changes in the prevalence of influenza vaccination and strength of association of factors predicting influenza vaccination over time: Results of two population-based surveys. Vaccine. 2007;25:8279–8289. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JC, Nichol KL. Excess mortality due to pneumonia or influenza during influenza seasons among persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;161:441–446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PJ, Euler GL, Mootre GT, Ahmed F, Singleton JA. State-specific influenza vaccination coverage among adults aged ≥18 years – United States, 2003-04 and 2005-06 influenza seasons. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:953–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina A, Moir S, Orsega SM, Vasquez J, Miller NJ, Donoghue ET, Kottilil S, Gezmu M, Follmann D, Vodeiko GM, Levandowski RA, Mican JM, Fauci AS. Compromised B cell responses to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1442–1450. doi: 10.1086/429298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Interview Survey [Accessed October 10, 2009];Self-reported influenza vaccination coverage trends 1989-2008 among adults by age group, risk group, race/ethnicity, heath-care worker status, and pregnancy status, United States. 2008 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/pdf/NHIS89_08fluvaxtrendtab.pdf.

- Nexøe J, Kragstrup J, Sogaard J. Decision on influenza vaccination among the elderly: A questionnaire study based on the Health Belief Model and the Multidimensional Locus of Control Theory. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1999;17:105–110. doi: 10.1080/028134399750002737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuzil KM, Reed GW, Mitchel EF, Jr., Griffin MR. Influenza-associated morbidity and mortality in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 1999;281:901–907. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuzil KM, Coffey CS, Mitchel EF, Griffin MR. Cardiopulmonary hospitalizations during influenza season in adults and adolescents with advanced HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:304–307. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200311010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV infection from the US Department of Health and Human Services and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1 Infected Adults and Adolescents. Bethesda, MD; National Institute of Health: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan HM, Cheeseman SH, Lai KK, Ellison RT. Influenza in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients during the 1997-1998 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:604–606. doi: 10.1086/313985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri R, Veronelli A, Santambrogio C, Pontiroli AE. Impact of influenza vaccine on response to vaccination with pneumococcal vaccine in HIV patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:407–409. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and preventive health behavior. In: Becker MH, editor. The Health Belief Model and personal health behavior. Charles B. Slack Inc; Thorofare, New Jersey: 1974. pp. 27–59. [Google Scholar]

- Safrin S, Rush JD, Mills J. Influenza in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Chest. 1990;98:33–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KL, Neale AV, Northrup J, Monsur J, Patel DA, Tobar R, Wortley PM. Racial similarities in response to standardized offer of influenza vaccination. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:346–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skov T, Deddens J, Petersen MR, Endahl L. Prevalence proportion ratios: estimation and hypothesis testing. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:91–95. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorvillo FJ, Nahlen BL. Influenza immunization for HIV-infected persons in Los Angeles. Vaccine. 1995;13:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)98261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker SA, Treanor JJ, Paxton WB, Wallace MR. Efficacy of influenza vaccination in HIV-infected persons: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:430–433. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-6-199909210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;249:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurn JR, Henry K. Influenza A pneumonitis in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Chest. 1989;95:807–810. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington DC: Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. (2nd ed) 2008

- Wortley PM, Farizo KM. Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination levels among HIV-infected adolescents and adults receiving medical care in the United States. AIDS. 1994;8:941–944. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka H, Teruya K, Tanaka M, Kikuchi Y, Takahashi T, Kimura S, Oka S. Efficacy and immunologic responses to influenza vaccine in HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RK, Raymund M, Janosky JE, Nowalk MP, Fine MJ. Sensitivity and specificity of patient self-report of influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccinations among elderly outpatients in diverse patient care strata. Vaccine. 2003;21:1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocchetti C, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA. Relationship between prevalence rate ratios and odds ratios in cross-sectional studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:220–223. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.