Abstract

With the analysis of complex, messy data sets, the statistics community has recently focused attention on “reproducible research,” namely research that can be readily replicated by others. One standard that has been proposed is the availability of data sets and computer code. However, in some situations, raw data cannot be disseminated for reasons of confidentiality or because the data are so messy as to make dissemination impractical. For one such situation, we propose 2 steps for reproducible research: (i) presentation of a table of data and (ii) presentation of a formula to estimate key quantities from the table of data. We illustrate this strategy in the analysis of data from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, which investigated the effect of the drug finasteride versus placebo on the period prevalence of prostate cancer. With such an important result at stake, a transparent analysis was important.

Keywords: Categorical data, Maximum likelihood, Missing data, Multinomial–Poisson transformation, Propensity-to-be-missing score, Randomized trials

1. INTRODUCTION

The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) investigated the effect of finasteride versus placebo on the period prevalence of prostate cancer determined by biopsy (Thompson and others, 2003). The PCPT randomized 18 882 men to receive either placebo or finasteride over 7 years. At annual intervals, men in both arms were scheduled to receive tests for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and also a digital rectal examination (DRE). If PSA was elevated or DRE indicated an abnormal finding, a biopsy was recommended. A biopsy was also offered at the end of the study to all living participants who had not been previously diagnosed with prostate cancer. A nonrandom sample of participants with prostate cancer on biopsy received surgery. The original endpoint was prostate cancer on biopsy. However, due to problems with interpreting this endpoint, it was later decided that a more relevant endpoint was prostate cancer determined on surgery and classified as either low grade (less severe) or high grade (more severe) based on a Gleason score (GS). The analysis is complicated because endpoint data were missing in 2 stages, biopsy and surgery following biopsy, both of which depended on whether or not biopsy was recommended and the grade on biopsy.

Three recent papers proposed different ways to estimate the effect of finasteride on high-grade prostate cancer ascertained by surgery in the presence of missing data (Pinsky and others, 2008; Redman and others, 2008; Shepherd and others, 2008). However, none of these papers was conducive to reproducibility. A reproducible and transparent analysis is important because the data are very complex and the results could affect a large number of men who currently receive finasteride for benign conditions.

One standard for reproducibility is the availability of data sets and computer code (Peng, 2009). However, due to confidentiality considerations and the messiness of the data, it was not feasible to disseminate the raw data. Instead, we chose another approach to reproducible research, namely presenting tables of counts and reporting simple closed-form maximum likelihood estimates. Please also see the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online for additional clinical background and important documentation for reproducible research on definitions, classification of subjects, derivations, and calculations.

2. DATA TABLES

We define

X = randomization group with x = 0 if placebo and x = 1 if finasteride,

A = indicator of biopsy recommendation with a = 1 if positive recommendation and 0 otherwise,

Y = the prostate cancer outcome if everyone were biopsied, with y = 0 if no cancer, y = 1 if low-grade cancer, and y = 2 if high-grade cancer,

D = “definitive” (for this study) prostate cancer outcome with d = 0 if no cancer on biopsy, 1 if low-grade prostate cancer on surgery, and 2 if high-grade prostate cancer on surgery,

MY = 0 if missing the biopsy and 1 otherwise,

MD = 0 if missing the surgery and 1 otherwise.

The data involve 3 types of counts:

mxa = the number of persons in randomization group x with biopsy recommendation a, missing a biopsy outcome and missing a surgery outcome,

nxay = the number of persons in randomization group x with biopsy recommendation a, biopsy outcome y, and missing surgery outcome,

kxayd = the number of persons in randomization group x with biopsy recommendation a, biopsy outcome y, and surgery outcome d.

Because persons who had surgery must have had prostate cancer on biopsy and hence had to be diagnosed with prostate cancer at surgery, kxayd is only defined for y ≠ 0 and d ≠ 0. Investigators were interested in 2 possible definitions for high-grade prostate cancer, either a GS greater than or equal to 7 or a GS greater than or equal to 8 (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Data from PCPT using GS greater than or equal to 7 as the definition of high-grade prostate cancer

| Persons without a biopsy and without surgery (mxa) | ||||

| Randomization group (x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | |||

| Placebo | No | 3955 | ||

| Yes | 215 | |||

| Finasteride |

No | 4169 | ||

| Yes |

214 |

|||

| Persons with biopsy but no surgery (nxay) | ||||

| Randomization group (x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | Biopsy outcome (y) |

||

| No cancer | GS < 7 | GS ≥ 7 | ||

| Placebo | No | 3675 | 417 | 78 |

| Yes | 479 | 249 | 104 | |

| Finasteride |

No | 3791 | 230 | 75 |

| Yes |

458 |

145 |

132 |

|

| Persons with biopsy and surgery (kxayd) | ||||

| Randomization group (x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | Surgery outcome (d) |

||

| Biopsy outcome (y) | GS < 7 | GS ≥ 7 | ||

| Placebo | No | GS < 7 | 83 | 19 |

| GS ≥ 7 | 8 | 13 | ||

| Yes | GS < 7 | 83 | 33 | |

| GS ≥ 7 | 9 | 46 | ||

| Finasteride | No | GS < 7 | 50 | 6 |

| GS ≥ 7 | 7 | 14 | ||

| Yes | GS < 7 | 44 | 23 | |

| GS ≥ 7 | 10 | 55 | ||

Table 2.

Data from PCPT using GS greater than or equal to 8 as the definition of high-grade prostate cancer

| Persons without a biopsy and without surgery (mxa) | ||||

| Randomization group (x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | |||

| Placebo | No | 3955 | ||

| Yes | 215 | |||

| Finasteride | No | 4169 | ||

| Yes | 214 | |||

| Persons with biopsy but no surgery (nxay) | ||||

| Randomization group (x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | Biopsy outcome (y) |

||

| No cancer | GS < 8 | GS ≥ 8 | ||

| Placebo | No | 3675 | 488 | 7 |

| Yes | 479 | 316 | 37 | |

| Finasteride | No | 3791 | 291 | 14 |

| Yes | 458 | 231 | 46 | |

| Persons with biopsy and surgery (kxayd) | ||||

| Randomization group(x) | Biopsy recommendation (a) | Surgery outcome (d) |

||

| Biopsy outcome (y) | GS < 8 | GS ≥ 8 | ||

| Placebo | No | GS < 8 | 120 | 0 |

| GS ≥ 8 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Yes | GS < 8 | 152 | 4 | |

| GS ≥ 8 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Finasteride | No | GS < 8 | 70 | 1 |

| GS ≥ 8 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Yes | GS < 8 | 101 | 6 | |

| GS ≥ 8 | 12 | 12 | ||

3. A TRANSPARENT ANALYSIS

We analyzed the data in the tables using a transparent approach involving closed-form maximum likelihood estimates. The parameter of interest is the probability of “definitive” prostate cancer outcome d conditional on randomization group x,

| (3.1) |

Other parameters are the probability of cancer outcome y on biopsy conditional on randomization group x and definitive prostate cancer outcome d,

| (3.2) |

and the probability of biopsy recommendation a conditional on randomization group x, biopsy outcome y, and definitive prostate cancer outcome d,

| (3.3) |

We make 2 reasonable assumptions.

ASSUMPTION 3.1

The probability of missing a biopsy outcome depends on randomization group x and biopsy recommendation a, but not biopsy outcome y, namely πxa = pr(MY = 0|x,a) = pr(MY = 0|x,a,y).

ASSUMPTION 3.2

The probability of missing a surgery outcome following a biopsy depends on randomization group x, biopsy recommendation a, and outcome of biopsy y, but not the outcome of the surgery d, namely γxay = pr(MD = 0|x,a,y,MY = 1) = pr(MD = 0|x,a,y,d,MY = 1).

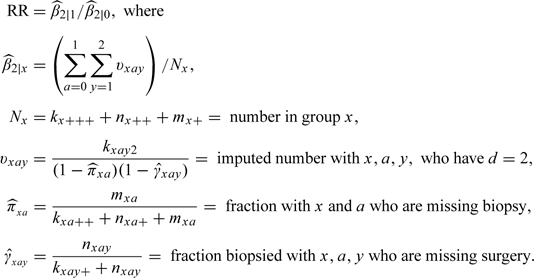

Because the model is saturated, we computed maximum likelihood estimates by setting observed cell counts equal to their expected values. Let “+” in a subscript denote summation. The maximum likelihood estimate of the relative risk (RR) for finasteride versus placebo group of high-grade prostate cancer (d = 2) is

|

(3.4) |

The estimated variance of RR was computed using the multinomial–Poisson transformation (Baker, 1994). We also computed estimates after adjusting for baseline variables using propensity-to-be-missing scores (Baker and others, 2006).

4. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results in Table 3, we draw 2 clinically important conclusions. First, finasteride likely lowers the risk of high-grade prostate cancer defined as a GS of 7 or greater, with a point estimate indicating a lower risk under finasteride and an upper bound of the 95% confidence interval indicating a very slight increase in risk (hence borderline statistical significance). Second, finasteride possibly increases the risk of high-grade prostate cancer defined as a GS of 8 or greater, with a point estimate indicating higher risk under finasteride but a lower bound of the 95% confidence interval indicating a substantial decrease in risk (hence statistically not significant). The main caveats, shared by all analyses of the PCPT data, are unmeasured confounders, misclassification of data, and lack of a definitive prostate cancer mortality endpoint. Although the results are qualitatively similar to previous results, it does not diminish the clinical importance of this analysis. Because our basic analysis is transparent and reproducible, it should carry extra weight with the clinical community.

Table 3.

Estimated RRs for high-grade prostate cancer for finasteride versus placebo (95% confidence intervals)

| Definition of high-grade prostate cancer as GS |

||

| 7 or above | 8 or above | |

| Our method unadjusted† | 0.83 (0.65, 1.05) | 1.53 (0.85, 2.75) |

| Adjusted‡ | 0.82 (0.64, 1.06) | 1.40 (0.71, 2.76) |

| Redman and others (2008) | 0.73 (0.56,0.96) | 1.25§ |

| Pinsky and others (2008) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.06) | 1.39 (0.79, 2.50) |

Based on family history, race, age. See supplementary material available at Biostatistics online.

No confidence interval reported, said to be imprecise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org.

FUNDING

National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Prevention (5U10CA037429-25); Southwest Oncology Group CCOP Research Base, PCPT/PCPT LTFU, and SELECT Programs; Division of Cancer Prevention in the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Thompson, the principal investigator for PCPT, for facilitating our use of the data, Cathy Tangen and Phyllis Goodman for assistance in processing the data, and Mary Redman for helpful comments. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Baker SG. The multinomial-Poisson transformation. The Statistician. 1994;43:495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SG, Fitzmaurice G, Freedman LS, Kramer BS. Simple adjustments for randomized trials with nonrandomly missing or censored outcomes arising from informative covariates. Biostatistics. 2006;7:29–40. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky P, Parnes H, Ford L. Estimating rates of true high-grade disease in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Cancer Prevention Research. 2008;1:182–186. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-07-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RD. Reproducible research and Biostatistics. Biostatistics. 2009;10:405–408. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman MW, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Lucia S, Coltman CA, Jr, Thompson IM. Finasteride does not increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer: a bias-adjusted modeling approach. Cancer Prevention Research. 2008;1:174–181. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd BE, Redman MW, Ankerst DP. Does finasteride affect the severity of prostate cancer? A causal sensitivity analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103:1392–1404. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Miller GJ, Ford LG, Lieber MM, Cespedes RD, Atkins JN, Lippman SM and others. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.