Abstract

Research interest in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) has grown dramatically in the past decade, particularly among cancer biologists. There are at least two reasons for this: first, the discovery in the year 2000 that LAM cells carry TSC2 gene mutations, linking LAM with cellular pathways including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis, and allowing the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)-regulated pathways that are believed to underlie LAM pathogenesis to be studied in cells, yeast, Drosophila, and mice. A second reason for the rising interest in LAM is the discovery that LAM cells can travel to the lung, including repopulating a donor lung after lung transplantation, despite the fact that LAM cells are histologically benign. This “benign metastasis” underpinning suggests that elucidating LAM pathogenesis will unlock a set of fundamental mechanisms that underlie metastatic potential in the context of a cell that has not yet undergone malignant transformation. Here, we will outline the data supporting the metastatic model of LAM, consider the biochemical and cellular mechanisms that may enable LAM cells to metastasize, including both cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous factors, and highlight a mouse model in which estrogen promotes the metastasis and survival of TSC2-deficient cells in a MEK-dependent manner. We propose a multistep model of LAM cell metastasis that highlights multiple opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Taken together, the metastatic behavior of LAM cells and the involvement of tumor-related signaling pathways lead to optimism that cancer-related paradigms for diagnosis, staging, and therapy will lead to therapeutic breakthroughs for women living with LAM.

Introduction

A“perfect storm,” according to Wikipedia, is the simultaneous occurrence of weather events which, taken individually, would be far less powerful than the storm resulting of their chance combination. Our current understanding suggests that LAM cells exist in an unusual milieu of cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous events, including mTOR pathway-driven proliferation as a consequence of TSC2 gene mutations, VEGF-D-driven lymphatic recruitment facilitating dissemination, and estrogen-driven cellular survival, which allows disseminated cells to resist anoikis and persist in the circulation. We hypothesize that this simultaneous occurrence of pro-metastatic cellular events allows LAM cells to despite the fact that they are histologically benign. Therapeutically disrupting even one of these pro-metastatic factors could dramatically reduce the metastatic potential of LAM cells.

Genetic Data Support a Metastatic Model of LAM Pathogenesis

LAM can occur in women with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), who carry germline TSC1 or TSC2 gene mutations (TSC-LAM), or in women who do not have TSC (sporadic LAM). TSC is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by seizures, mental retardation, autism, cerebral cortical tubers, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas facial angiofibromas, cardiac rhabdomyomas, renal angiomyolipomas, renal cysts, and LAM.1 Cystic lung disease consistent with LAM occurs in about 30% of women with TSC, although in most cases it is asymptomatic.2,3 TSC is caused by germline mutations in the TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34 or the TSC2 gene on chromosome 16p13.1

Angiomyolipomas are benign tumors found in the kidneys of about 50% of women with the sporadic form of LAM and in the vast majority of patients with TSC.4 The first evidence of a genetic link between TSC and sporadic LAM was from studies of renal angiomyolipomas from women with the sporadic form of LAM, when it was found that these angiomyolipomas have loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the TSC2 region of chromosome 16p13.5 Interestingly, in this first paper, TSC2 LOH was also found in multiple lymph nodes from a woman with extrapulmonary LAM. In retrospect, these genetic findings in extrapulmonary LAM may have been the first clue of LAM cell metastasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetic Evidence Support that LAM Is a Metastatic Disease

| References | |

|---|---|

| TSC1 or TSC2 mutations | |

| TSC2 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in sporadic LAM and angiomyolipomas | 5 |

| Somatic bi-allelic TSC2 mutations in microdissected sporadic LAM cells | 6 |

| Metastatic evidence | |

| LAM cells and angiomyolipoma cells from sporadic LAM patients have identical TSC2 mutations; mutations are not found in normal lung or kidney, or in lymphocytes | 6, 10 |

| LAM and angiomyolipoma cells from sporadic LAM patients have LOH of the same alleles in the TSC2 region | 11 |

| Recurrent LAM cells after lung transplantation are derived from the recipient's original LAM cells | 12, 13 |

LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

After identifying TSC2 gene region LOH in sporadic LAM-associated angiomyolipomas, we used single-stand conformation polymorphism analysis (SSCP) to search for mutations in all 41 exons of TSC2. TSC2 mutations (point mutations or small deletions) were identified in five of seven angiomyolipomas from women with sporadic LAM in which TSC2 LOH had been previously found.6 Some of these were identical to germline mutations that had been previously reported in TSC patients. This work clearly established that inactivation of both alleles was involved in sporadic LAM angiomyolipomas, consistent with the two-hit tumor suppressor gene model,7 which was originally proposed by Alfred Knudson. Dr. Knudson was an early advocate of TSC and LAM research at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, PA, and working with Raymond Yeung, identified the Tsc2 gene mutation in the Eker rat model, which develops renal carcinomas and uterine leiomyomas.8

After identifying bi-allelic TSC2 mutations in sporadic LAM-associated angiomyolipomas, laser capture microdissection was used to isolate LAM cells from these patients. TSC2 mutations identical to those in the angiomyolipomas were found in the microdissected LAM cells of four of the patients.6 The presence of same TSC2 mutation in LAM cells and angiomyolipoma cells, but not in normal kidney, normal lung, or peripheral blood lymphocytes, led to the “benign metastasis” model of LAM pathogenesis.9 Subsequently, Sato et al. confirmed these findings in Japanese patients with LAM,10 and Yu et al. demonstrated with the use of multiple microsattelite markers across chromosome 16p13 that the region of LOH appeared to be the same between the angiomyolipomas and the microdissected LAM cells from the same patient.11

These data were consistent with a metastatic model. However, there were several published case reports of recurrent LAM after lung transplantation in which a woman with LAM had received a male donor lung, and in which Y chromosome fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) appeared to indicate that the recurrent LAM cells contained a Y chromosome and therefore arose from the donor lung. To address the genetic origin of recurrent LAM cells more definitively, we studied microdissected recurrent LAM cells from a woman who had received a male-donor lung transplantation, and compared them with her “native” LAM cells prior to the transplantation. The same somatic TSC2 mutation, in exon 18 of TSC2, was present in LAM cells before and after the lung transplantation,12 thereby establishing that the recurrent LAM cells were genetically related to the original LAM, pretransplantation. In addition, Y-chromosome FISH combined with HMB-45 immunofluorescent staining revealed that her recurrent LAM cells lacked a Y chromosome, consistent with the mutational data and a model in which the recurrent LAM cells arose from her original LAM cells, and not from the male donor lung. In retrospect, in the earlier studies in which it appeared that the recurrent LAM cells contained a Y chromosome, it seems likely that the close interdigitation of LAM cells with reactive stromal cells made the in situ hybridization studies difficult to interpret, a conclusion which Bittman et al. have now validated.13

LAM Cells Are Present in Blood and Other Body Fluids

The mechanisms through which LAM cells metastasize were mysterious until 2004, when a major finding was made by Crooks et al. (Table 2).14 Using a density gradient centrifugation separation designed for circulating cancer cell enrichment, they isolated LAM cells from the peripheral blood of women with the sporadic form of LAM. LAM cells, validated by the presence of chromosome 16p13 LOH, were found in blood from 33 of 60 (55%) women with LAM, in urine from 11 of 14 (79%) sporadic LAM patients with angiomyolipomas, and in chylous fluid from one of three (33%) women with LAM. Further work by this group used the expression of surface glycoprotein CD44 and its splice variant CD44V6 to isolate LAM cells from primary cultures derived from explanted lungs of 12 women with the sporadic form of LAM.15 A great deal remains to be learned about these circulating LAM cells, including their origin, their relationship to pathogenesis, their potential use diagnostically, and their role as a biomarker of disease severity and/or response to therapy.

Table 2.

Cellular Process that May Contribute to LAM Cell Metastasis

| References | |

|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton and motility | |

| TSC1/TSC2 regulate Rho and cell motility | 16–19 |

| Circulating LAM cells | |

| LAM cells with TSC2 LOH detected in blood of LAM patients | 14,15 |

| Expression of cell surface markers and chemokines | |

| LAM cells express CD44, CD44v6, CCR2, CCR10, CXCR1, CSCR2, and CSCR4 | 15, 46 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 enhances migration of LAM cells | 46 |

| Proteinases | |

| LAM cells express cathepsin-K, MMP-2, − 9, − 14, and TIMP-1, − 2, − 3 | 20–24, 27 |

| MMP inhibition by doxycycline improves pulmonary function | 25 |

| MMP-2 expression in TSC2-null cells is TSC2-dependent but rapamycin insensitive | 26 |

| Lymphatic recruitment | |

| LAM are surrounded by lymphatic endothelial cells | 39–41, 47 |

| VEGF-D is expressed by LAM cells and is elevated in the serum of LAM patients | 41–43 |

| Role of estrogen | |

| Estrogen stimulates growth of TSC2-null ELT3 cells | 33–35, 38 |

| Estrogen activated MAPK and stimulated growth of angiomyolipoma cells from a sporadic LAM patient | 36 |

| LAM and antiomyolipoma cells express estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) and progesterone receptor (PgR) | 28–32 |

| Estrogen promotes survival, metastsis, and lung colonization of ELT3 cells, and inhibits anoikis | 38 |

LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Loss of TSC1 and/or TSC2 Enhances Cell Migration and Invasion

The cell autonomous mechanisms underlying the metastasis of LAM cells are likely to include abnormalities of the actin cytoskeleton. Lamb et al. reported that TSC1 expression increases Rho activity, enhances focal adhesion and stress fiber formation via a direct interaction with the ezrin–radixin–moesin family of cytoskeletal proteins.16 We found that cells lacking Tsc2 have lower levels of Rho activity, enhanced chemotactic cell migration, and decreased cell adhesion.17 Goncharova et al. 18,19 found that TSC2 regulates cell migration and impacts the activity of both Rac and Rho. Interestingly, they found that the N-terminus of TSC2 was sufficient to inhibit cell migration and activate Rac1, suggesting that this is independent of the GTPase-activiating protein (GAP) activity of tuberin and independent of Rheb.

Expression of Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Circulation of LAM Cells

Numerous studies have shown that MMPs or regulators of MMPs are expressed in LAM cells. These include expression of MMP-2,20–22 MMP-2 activator, membrane type (MT) MT-1-MMP or MMP-14,22–24 and MMP9.21 The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase TIMP-1, TIMP − 2, and TIMP − 3 were expressed at low level in LAM cells.21,22 Doxycycline treatment to block MMP activity resulted in an improvement in the respiratory function of one patient.25 A recent study by Lee et al. found that cells derived from a LAM-associated angiomyolipoma exhibited higher of MMP2 activity, and that this was not sensitive to rapamycin, suggesting mTORC1-independence.26

Cathepsin-K is a cysteine protease that can degrade extracellular matrix (ECM). Chilosi et al. studied 12 cases of pulmonary LAM and found strong immunoreactivity for cathepsin-K in LAM cells in all cases.27 These studies suggest that expression and/or activation of proteases may contribute to ECM remodeling, facilitating the entry of LAM cells to the circulation. Protease expression and activation may also contribute to cystic degeneration of the lung in LAM patients.

Estrogen Promotes the Survival and Metastasis of Tsc2-null Cells

The role of estrogen in LAM pathogenesis remains a key research question, highlighted by the exceptionally high female predominance of LAM and the possibility of therapeutic benefit of targeting the estrogen axis. Many studies have shown estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression by LAM cells,28–32 and our group has found that angiomyolipomas from sporadic LAM patients also express ERα and PR.31 Howe et al. found that estrogen promotes the proliferation of Tsc2-null ELT3 cells in vitro and the growth of xenograft subcutaneous tumors in vivo.33 Estrogen treatment of Tsc2-null ELT3 cells or TSC2-null LAM-associated angiomyolipoma cells is associated with strong and rapid (5 min) ERK-1/2 activation, suggesting that estrogen may have cytoplasmic “nongenomic” effects on LAM cells as well as genomic effects.34–36 An interaction between tuberin and the estrogen receptor has been observed,35–37 although its role in LAM pathogenesis remains unknown.

We have studied Tsc2-deficient Eker rat derived ELT3 cells that are estrogen-receptor positive and estrogen responsive,33 found that estrogen promotes a five-fold increase in the number of pulmonary metastasis in ovariectomized mice carrying subcutaneous tumors. In male mice, estrogen treatment results in a three-fold increase in lung metastasis of ELT3 cells. Estrogen also enhances the number of circulating tumor cells and the survival of intravenously injected ELT3 cells.38 In vitro, estrogen-treated ELT3 cells exhibit induced resistance to anoikis and decreased levels of caspase-3 cleavage. Using the Xenogen bioluminescent imaging (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA), estrogen treatment causes a two-fold increase in lung colonization of intravenously injected ELT3-luciferase cells at 3 h, and a five-fold increase at 24 h (Fig. 1). Estrogen treatment of the ELT3 cells is associated with activation of MAPK both in vitro and in vivo, and the MEK inhibitor CI-1040 completely blocks estrogen-promoted lung metastasis.38 These data suggest that a major mechanism underlying the female predominance of LAM may be estrogen-enhanced survival and resistance to anoikis, thereby promoting the survival of circulating LAM cells.

FIG. 1.

Estrogen promotes the lung colonization of Tsc2-null ELT3 cells. Female ovariectomized CB17-SCID mice were implanted with estradiol (E2) (n = 3) or placebo (n = 3) pellets (2.5 mg, 90-day release) one week prior to cell injection. 2 × 105 ELT3-luciferase cells were injected intravenously. Lung colonization was measured using bioluminescence at 1, 3, and 24 h after injection. (A) Representative images are shown. (B) Total photon flux/second present in the chest regions was quantified and compared between E2 and placebo-treated animals. At 1 h, the bioluminescence in the chest region was similar. By 3 h, the photon flux in the chest region was 2-fold higher in the E2-treated mice, and by 24 h it was 5-fold higher. *p = 0.05, Student's t test. (C) Lungs were dissected 24 h post-cell injection and bioluminescence was imaged in Petri dishes. From Yu et al. (38).

Role of the Lymphatic System

Kumasaka et al. found that lymphatics were extremely abundant in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAM, using a specific marker for lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) Flt-4 (VEGFR-3). In contrast, only modest evidence of capillary endothelial cells was observed based on CD31 staining. In addition, expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C was detected in LAM cells, and clusters of LAM cells surrounded by Flt-4 positive cells were observed in the dilated lymphatic vessels, suggesting a specific recruitment of LEC to LAM cells.39

Subsequently, the same group found LAM cell clusters lined by LEC in chylous fluid, the thoracic duct, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes in five of five LAM patients.40 These findings suggested that LAM cells are surrounded by and may recruit lymphatic capillaries, providing entry to the lymphatic circulation and promoting metastasis.

Seyama et al. found that the serum level of VEGF-D was significantly higher in 44 LAM patients (average 1069.3 pg/mL) compared to 22 healthy controls (average 295.9 pg/mL). All LAM cells from 44 pulmonary LAM specimens exhibited immunoreactivity for VEGF-D, suggesting that LAM cells are secreting VEGF-D.41 Glasgow et al.42 and Young et al 43 also found that VEGF-D levels are higher in LAM patients than healthy volunteers. In addition to its potential role in LAM pathogenesis and as a target for LAM therapy, VEGF-D may be useful diagnostically and/or as a biomarker of disease in LAM patients with lymphatic involvement.

How Can the Metastatic Model Contribute to Early Detection, Biomarker Development, Therapy?

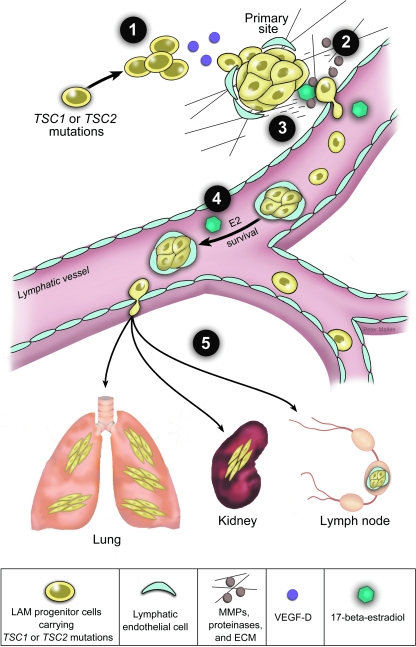

The original “perfect storm” hit the northeast United States on October 31, 1991, driven by three separate weather systems: warm air coming from one direction, cool dry air coming from another, and moisture provided by a hurricane. That same year, a study by Shepherd et al. found that LAM was the fourth most common cause of TSC-associated death.44 At that point, the TSC genes had not yet been cloned, the genetic links between TSC and sporadic LAM were unknown, and the possibility that LAM cells were metastatic had not been considered. We now believe that LAM is driven by a confluence of prometastic factors that include mTOR activation, lymphatic recruitment, extracellular matrix remodeling, and estrogen promoted cell survival (Fig. 2). Like the perfect storm, even a modest change in any one event contributing to LAM pathogenesis could lessen the overall severity considerably. There are multiple potential sites of therapeutic intervention, including blocking the recruitment of lymphatic vasculature, inhibiting proteases, and inducing apoptosis by inhibiting estrogen or the estrogen receptor.

FIG. 2.

Multistep model of lymphatic-mediated and estrogen-promoted metastasis of LAM progenitor cells. Genetic studies indicate that LAM progenitor cells carrying TSC1 or TSC2 mutations metastasize to lymph nodes, kidneys, and lungs. Collective studies suggest that LAM cell metastasis is driven by several distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms. We propose a multistep model of lymphatic and estrogen-associated metastais. Step 1: LAM-progenitor cells secrete VEGF-D and recruit lymphatic endothelial cells. Step 2: Estrogen induces expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) facilitating invasion. Step 3: LAM cells enter the lymphatic vessels in clusters covered by lymphatic endothelial cells. Step 4: Estrogen enhances the survival of LAM cells in circulation. Step 5: Metastatic lesions develop in distant organs including lungs, kidney. and lymph nodes.

Footnotes

Research in our laboratory is supported by grants from The Adler Foundation, the LAM Treatment Alliance, the LAM Foundation, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Mallen (Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard Medical School) for the graphic art. This article is dedicated to Alfred Knudson, M.D., Ph.D., Ann Petri, Ph.D., and William A. Petri.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Crino PB. Nathanson KL. Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franz DN. Brody A. Meyer C. Leonard J. Chuck G. Dabora S. Sethuraman G. Colby TV. Kwiatkowski DJ. McCormack FX. Mutational and radiographic analysis of pulmonary disease consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia in women with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:661–668. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2011025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss J. Avila NA. Barnes PM. Litzenberger RA. Bechtle J. Brooks PG. Hedin CJ. Hunsberger S. Kristof AS. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:669–671. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2101154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henske EP. Tuberous sclerosis and the kidney: From mesenchyme to epithelium, and beyond. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:854–857. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1795-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolarek TA. Wessner LL. McCormack FX. Mylet JC. Menon AG. Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: Chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:810–815. doi: 10.1086/301804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carsillo T. Astrinidis A. Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6085–6090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudson A. Mutation and cancer: Statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeung RS. Xiao GH. Jin F. Lee WC. Testa JR. Knudson AG. Predisposition to renal carcinoma in the Eker rat is determined by germ-line mutation of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11413–11416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henske EP. Metastasis of benign tumor cells in tuberous sclerosis complex. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:376–381. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato T. Seyama K. Fujii H. Maruyama H. Setoguchi Y. Iwakami S. Fukuchi Y. Hino O. Mutation analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Hum Genet. 2002;47:20–28. doi: 10.1007/s10038-002-8651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu J. Astrinidis A. Henske EP. Chromosome 16 loss of heterozygosity in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1537–1540. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2104095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karbowniczek M. Astrinidis A. Balsara BR. Testa JR. Lium JH. Colby TV. McCormack FX. Henske EP. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:976–982. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-969OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bittmann I. Rolf B. Amann G. Löhrs U. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis after single lung transplantation: New insights into pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:95–98. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crooks DM. Pacheco–Rodriguez G. DeCastro RM. McCoy JP Jr. Wang JA. Kumaki F. Darling T. Moss J. Molecular and genetic analysis of disseminated neoplastic cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17462–17467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407971101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pacheco–Rodriguez G. Steagall WK. Crooks DM. Stevens LA. Hashimoto H. Li S. Wang JA. Darling TN. Moss J. TSC2 loss in lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells correlated with expression of CD44v6, a molecular determinant of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10573–10581. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb RF. Roy C. Diefenbach TJ. Vinters HV. Johnson MW. Jay DG. Hall A. The TSC1 tumour suppressor hamartin regulates cell adhesion through ERM proteins and the GTPase Rho. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:281–287. doi: 10.1038/35010550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astrinidis A. Cash TP. Hunter DS. Walker CL. Chernoff J. Henske EP. Tuberin, the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 tumor suppressor gene product, regulates Rho activation, cell adhesion, and migration. Oncogene. 2002;21:8470–8476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goncharova E. Goncharov D. Noonan D. Krymskaya VP. TSC2 modulates actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion through TSC1-binding domain and the Rac1 GTPase. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1171–1182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goncharova EA. Goncharov DA. Lim PN. Noonan D. Krymskaya VP. Modulation of cell migration and invasiveness by tumor suppressor TSC2 in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:473–480. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0374OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferri N. Carragher NO. Raines EW. Role of discoidin domain receptors 1 and 2 in human smooth muscle cell-mediated collagen remodeling: Potential implications in atherosclerosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi T. Fleming MV. Stetler–Stevenson WG. Liotta LA. Moss J. Ferrans VJ. Travis WD. Immunohistochemical study of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhe X. Yang Y. Jakkaraju S. Schuger L. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 downregulation in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Potential consequence of abnormal serum response factor expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:504–511. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0124OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsui K. Takeda K. Yu ZX. Travis WD. Moss J. Ferrans VJ. Role for activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:267–275. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0267-RFAOMM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsui KK. Riemenschneider W. Hilbert SL. Yu ZX. Takeda K. Travis WD. Moss J. Ferrans VJ. Hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1642–1648. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1642-HOTIPI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moses MA. Harper J. Folkman J. Doxycycline treatment for lymphangioleiomyomatosis with urinary monitoring for MMPs. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2621–2622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc053410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee PS. Tsang SW. Moses MA. Trayes–Gibson Z. Hsiao LL. Jensen R. Squillace R. Kwiatkowski DJ. Rapamycin-insensitive up-regulation of MMP2 and other genes in TSC2-deficient LAM-like cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:227–234. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0050OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chilosi M. Pea M. Martignoni G. Brunelli M. Gobbo S. Poletti V. Bonetti F. Cathepsin-k expression in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:161–166. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger U. Khaghani A. Pomerance A. Yacoub MH. Coombes RC. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and steroid receptors. An immunocytochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:609–614. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brentani MM. Carvalho CR. Saldiva PH. Pacheco MM. Oshima CT. Steroid receptors in pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis. Chest. 1984;85:96–99. doi: 10.1378/chest.85.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham ML., 2nd Spelsberg TC. Dines DE. Payne WS. Bjornsson J. Lie JT. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis: with particular reference to steroid-receptor assay studies and pathologic correlation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logginidou H. Ao X. Russo I. Henske EP. Frequent estrogen and progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in renal angiomyolipomas from women with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 2000;117:25–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tawfik O. Austenfeld M. Persons D. Multicentric renal angiomyolipoma associated with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Case report, with histologic, immunohistochemical, and DNA content analyses. Urology. 1996;48:476–480. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howe SR. Gottardis MM. Everitt JI. Walker C. Estrogen stimulation and tamoxifen inhibition of leiomyoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4996–5003. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finlay GA. Hunter DS. Walker CL. Paulson KE. Fanburg BL. Regulation of PDGF production and ERK activation by estrogen is associated with TSC2 gene expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C409–C418. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00482.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finlay GA. York B. Karas RH. Fanburg BL. Zhang H. Kwiatkowski DJ. Noonan DJ. Estrogen-induced smooth muscle cell growth is regulated by tuberin and associated with altered activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta and ERK-1/2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23114–23122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J. Astrinidis A. Howard S. Henske EP. Estradiol and tamoxifen stimulate LAM-associated angiomyolipoma cell growth and activate both genomic and nongenomic signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L694–L700. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00204.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.York B. Lou D. Panettieri RA Jr. Krymskaya VP. Vanaman TC. Noonan DJ. Cross-talk between tuberin, calmodulin, and estrogen signaling pathways. FASEB J. 2005;19:1202–1204. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3142fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu JJ. Robb VA. Morrison TA. Ariazi EA. Karbowniczek M. Astrinidis A. Wang C. Hernandez–Cuebas L. Seeholzer LF. Nicolas E. Hensley H. Jordan VC. Walker CL. Henske EP. Estrogen promotes the survival and pulmonary metastasis of tuberin-null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2635–2640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810790106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumasaka T. Seyama K. Mitani K. Sato T. Souma S. Kondo T. Hayashi S. Minami M. Uekusa T. Fukuchi Y. Suda K. Lymphangiogenesis in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Its implication in the progression of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1007–1016. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126859.70814.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumasaka T. Seyama K. Mitani K. Souma S. Kashiwagi S. Hebisawa A. Sato T. Kubo H. Gomi K. Shibuya K. Fukuchi Y. Suda K. Lymphangiogenesis-mediated shedding of LAM cell clusters as a mechanism for dissemination in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1356–1366. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000172192.25295.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seyama K. Kumasaka T. Souma S. Sato T. Kurihara M. Mitani K. Tominaga S. Fukuchi Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D is increased in serum of patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2006;4:143–152. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2006.4.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glasgow CG. Avila NA. Lin JP. Stylianou MP. Moss J. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor-D levels in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis reflect lymphatic involvement. Chest. 2009;135:1293–1300. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young LR. Inoue Y. McCormack FX. Diagnostic potential of serum VEGF-D for lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:199–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0707517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shepherd CW. Gomez MR, Lie JT, Crowson CS. Causes of death in patients with tuberous sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:792–796. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strizheva GD. Carsillo T. Kruger WD. Sullivan EJ. Ryu JH. Henske EP, et al. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1, TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis, lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):253–258. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pacheco–Rodriguez G. Kumaki F. Steagall WK. Zhang Y. Ikeda Y. Lin JP. Billings EM. Moss J. Chemokine-enhanced chemotaxis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells with mutations in the tumor suppressor TSC2 gene. J Immunol. 2009;182:1270–1277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirama M. Atsuta R. Mitani K. Kumasaka T. Gunji Y. Sasaki S. Iwase A. Takahashi K. Seyama K. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis diagnosed by immunocytochemical and genetic analysis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis cell clusters found in chylous pleural effusion. Intern Med. 2007;46:1593–1596. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]