Abstract

Background

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is more severe and occurs at an earlier age in type 1 diabetes. Risk factors for this subclinical marker of atherosclerotic burden, like coronary artery disease (CAD) itself, are not fully identified. One postulated mechanism for the increased CAC observed in type 1 diabetes is the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). As certain collagen AGEs fluoresce, skin intrinsic fluorescence (SIF) can act as a novel marker of levels of collagen AGEs. We thus sought to determine the relationship between skin intrinsic fluorescence and CAC in type 1 diabetes.

Methods

One hundred five participants in the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications study of childhood-onset (age <17 years) type 1 diabetes who had previously undergone electron beam tomography scanning for CAC (80 of whom had follow-up data) had SIF measurements taken using the SCOUT DM® (VeraLight, Inc., Albuquerque, NM). Mean age and diabetes' duration were 49 and 40 years, respectively, at the time of SIF measurement.

Results

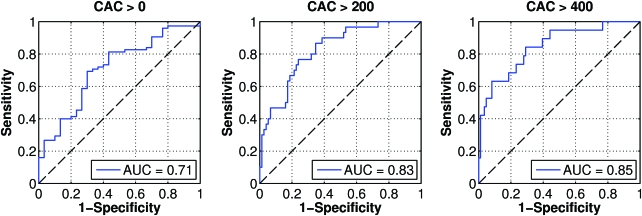

Seventy-one percent of the study participants had some measurable CAC that was univariately (but not after age adjustment) cross-sectionally associated with SIF (odds ratio = 2.51, 1.37–4.59). However, for CAC severity using natural logarithmically transformed scores, SIF was both univariately (P < 0.0001) and multivariably (P = 0.03) associated with CAC. This relationship was independent of age, a history of CAD, renal function, or renal damage. Receiver operator characteristic analyses revealed that the discriminative ability of SIF to detect CAC went from an area under the curve of 71% for the presence of any CAC to 85% for those with a CAC score >400.

Conclusions

The relationship between SIF and CAC appears stronger with more severe calcification. Given the strong relationship of CAC with CAD this finding has important implications and suggests that SIF maybe a useful marker of CAC/CAD risk and potentially a therapeutic target.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death in type 1 diabetes; however, risk factors for CAD in this population are incompletely understood. Coronary artery calcification (CAC), more severe and occurring at an earlier age in type 1 diabetes,1 is a subclinical marker of atherosclerotic burden2 and correlated with prevalent3 and future clinical CAD events.4–7 One postulated mechanism for the increased CAC observed in type 1 diabetes is the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Both AGEs8–10 and CAC are increased in type 1 diabetes, and AGEs have been shown to induce osteoblastic differentiation of microvascular pericytes,11 thereby increasing vascular calcification.

AGEs are macroprotein complexes formed by the Malliard reaction of reducing sugars with free amino groups on proteins, amino acids, or lipids.12 Many AGEs form molecular cross-links and fluoresce. As certain dermal collagen AGEs, such as pentosidine and crosslines, contain fluorescent cross-links,12 skin intrinsic fluorescence (SIF) can be quantified and act as a novel marker of collagen AGEs.13 SIF, determined by the SCOUT DM® (VeraLight, Inc., Albuquerque, NM) skin fluorescence reader, was recently found to be cross-sectionally associated with neuropathy, micro- and macroalbuminuria, and CAC and marginally with CAD in a preliminary analysis of 47 participants of the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications (EDC) study.14 However, only for CAC and neuropathy was a relationship observed independent of renal function, which is important because accumulation of AGEs and CAC is greatly accelerated in renal disease15 and renal function is tightly tied to AGE clearance.16 Accordingly, we sought to determine, in a larger sample, the relationship between SIF and CAC in type 1 diabetes; the participants from the earlier report are included in the present analyses. This work was presented in part in abstract form at the 68th and 69th annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.14 In a subsequent article we will report the results of the relationship between neuropathy and SIF.

Subjects and Methods

The EDC study cohort is a well-defined population (n = 658) with type 1 diabetes diagnosed before the age of 17 years at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA).17,18 Mean age and diabetes' duration at study baseline (1986–1988) were 28 and 19 years, respectively. Participants have been followed biennially by survey and medical examination. One hundred five participants (96% Caucasian) from the EDC study who had previously undergone electron beam tomography (EBT) scanning (C-150 scanner, GE Imatron, South San Francisco, CA) for CAC in either the 16th or 18th year of follow-up consented to participate in the Noninvasive Skin Spectroscopy Substudy for Diabetes Complications, a cross-sectional study, during the 20th year of the follow-up period. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh.

Eighty participants had previously had CAC measured during the 10-year follow-up period (1996–1998) and are included in a subanalysis of CAC progression. Threshold calcium determination was set using a density of 130 Hounsfield units in a minimum of two contiguous sections of the heart. Scans were triggered by electrocardiogram signals at 80% of the R-R interval. Total volume CAC scores were calculated based on isotropic interpolation19 and are used for analyses.

SIF covariate data were collected, as previously described, at the time of CAC assessment.17,18 Blood samples were assayed for lipids, lipoproteins, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and creatinine. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was determined by a heparin and manganese procedure, a modification20 of the Lipid Research Clinics method.21 Cholesterol was measured enzymatically.22 Non-HDL cholesterol was calculated as the difference between the total cholesterol and the HDL cholesterol. Original A1c was measured with the DCA 2000 analyzer (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY) and converted to Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)-aligned HbA1c values using regression formulas derived from duplicate analyses: DCCT HbA1c = (EDC HbA1c − 1.13)/0.81. Urinary albumin was determined immunonephelometrically. Height was measured using a stadiometer and weight using a balance beam scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (in kg) divided by the square of the height (in m). Blood pressure was measured by a random-zero sphygmomanometer according to a standardized protocol after a 5-min rest period. Blood pressure levels were analyzed, using the mean of the second and third readings. A history of CAD was defined as myocardial infarction, ischemia (Minnesota Codes 1.1–1.3, 4.1–4.3, 5.1–5.3, and 7.1), revascularization, or EDC clinic-diagnosed angina.

SIF was noninvasively measured from the skin of the volar forearm using three SCOUT DM skin fluorescence spectrometers.23,24 Skin fluorescence was excited with a light-emitting diode (LED) light source centered at 375 nm and was detected over the range of 441–496 nm. Skin reflectance measurements were acquired using the 375-nm LED as well as a broadband white LED as light sources in order to provide a characterization of light absorption in the skin, which is dominated by melanin and hemoglobin. These reflectance spectra were used in the intrinsic correction equation to compensate for distortion of the raw fluorescence by skin absorption25:

|

where λ is the emission wavelength. The measured fluorescence, F(λ), is divided by reflectance values at the excitation and emission wavelengths, Rx and Rm (λ), respectively. The reflectance values are adjusted by the dimensionless exponents, kx and km.14 For these analyses, kx = 0.6 and km = 0.2.

The resulting intrinsic fluorescence, f(λ), was integrated over the 441 to 496 nm spectral region to give the SIF score. Intra-subject skin variation in SIF assessed by the SCOUT DM had previously been determined in a large diabetes screening study of 2,589 individuals without preexisting diagnosis of diabetes, but at risk for developing type 2 diabetes. The age range of this cohort was 18–88 years old, 40% male and 60% female, with an ethnic breakdown of 62% white, 22% African American, 11% Hispanic, and 5% other. The inter-day Hoorn coefficient of variation (fasting vs. nonfasting) was 6.9% for SCOUT DM-measured SIF.

Statistical analyses

CAC volume scores were natural logarithmically transformed after adding 1 to their value. Student's t test and χ2 tests were used to examine univariate correlates of CAC prevalence. Logistic regression analysis with stepwise selection was used to determine the independent association of SIF with the prevalence of CAC. Receiver operator characteristic curves were used to determine the discriminative ability of SIF to detect CAC at thresholds of total volume CAC score of >0, >200, and >400. Spearman's correlation was used to determine the association of SIF with the severity of CAC, i.e., the total volume CAC score. Linear regression analysis with stepwise selection was used to determine the independent association of SIF with the severity of CAC. For the analysis of CAC progression, progression was defined as >2.5 change in the square-root transformed CAC score.26 Odds ratios (OR) and regression coefficients are expressed as per SD change in the continuous variables. The Hoorn coefficient of variation27 was used to determine intra-subject variation in the SIF measurement in a subset of participants.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants by the prevalence of CAC (at latest assessment) are presented in Table 1. Seventy-one percent of the study participants had some measureable CAC. Participants with CAC were older, had diabetes of longer duration, a higher SIF, a higher albumin excretion rate (AER), a greater prevalence of long-term complications of diabetes, and a marginally lower diastolic blood pressure, and were marginally more likely to be taking lipid or hypertension medication.

Table 1.

Characteristics of EDC Scout Participants by CAC (Total Volume Calcification Score) Status

| Characteristica | CAC positive (n = 75) | CAC negative (n = 30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIF | 0.033 (0.007) | 0.028 (0.006) | 0.0009 |

| Age (years) | 46.4 (6.6) | 39.1 (6.5) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes' duration (years) | 36.7 (6.7) | 31.5 (7.2) | 0.0006 |

| Sex (% female) | 57.33 (43) | 53.33 (16) | 0.71 |

| HbA1c (%) (n = 74; 28) | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.6 (1.4) | 0.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (74; 30) | 26.17 (4.64) | 25.14 (3.06) | 0.18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) (n = 74; 29) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.14 |

| AER (μg/min) (n = 73; 28) | 8.4 (4.0–47.3) | 4.1 (2.3–7.5) | 0.004 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| HDL (n = 73; 29) | 59.5 (17.0) | 59.4 (15.1) | 0.99 |

| Non-HDL (n = 73; 29) | 124.5 (28.0) | 125.9 (25.6) | 0.82 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic (n = 72; 29) | 118.8 (16.9) | 116.0 (10.3) | 0.31 |

| Diastolic (n = 72; 29) | 66.3 (9.3) | 70.1 (9.7) | 0.07 |

| CAD | 36.0 (27) | 16.7 (5) | 0.05 |

| Proliferative retinopathy | 64.0 (48) | 26.7 (8) | 0.0005 |

| Overt nephropathy | 32.0 (24) | 10.0 (3) | 0.03b |

| Distal symmetrical polyneuropathy | 69.3 (52) | 30.0 (9) | 0.0002 |

| Lower extremity arterial disease | 40.0 (3) | 10.0 (3) | 0.002b |

| History of smoking | 32.9 (24) | 24.1 (7) | 0.39 |

| ACE/ARB medication use (n = 73; 29) | 49.3 (36) | 27.6 (8) | 0.05 |

| Statin use (n = 73; 29) | 42.5 (31) | 20.7 (6) | 0.04 |

Data are mean (SD) or median (interquartile range) values or % (n). Risk factors, with the exception of SIF, were measured at the time of CAC assessment. ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blocker.

Values for n represent numbers of patients in the CAC-positive and CAC-negative groups.

By Fisher's exact P value.

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that each SD change in SIF was associated with a 2.5 greater likelihood for the prevalence of CAC (P = 0.003). However, after accounting for age, this relationship was only of marginal significance (OR = 1.88, 0.96–3.67; P = 0.07). Correlates of the prevalence of CAC were thus age and serum creatinine in fully stepwise multivariable analysis in which SIF and other previously identified univariate correlates, including BMI, from Table 1 were made available for modeling.

Figure 1 demonstrates the median (log 10) CAC score by tertiles of SIF. There was a marked increase in the severity of CAC with each increasing tertile of SIF. Figure 2 shows the discriminative ability to detect CAC at threshold scores of >0, >200, and <400, representing 71%, 30%, and 19% of the population, respectively. Although SIF shows minimal ability to detect the presence of any CAC, its discriminative ability increases with increasing threshold scores of total CAC. The area under the curve for the presence of CAC (a CAC score >0) is 71%. This increases to 82% at a threshold score of >200 and to 85% at a threshold score of >400. The Hoorn CV (intra-subject variance) of SIF was 4%.

FIG. 1.

Median (log 10) CAC by tertiles of SIF. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/dia.

FIG. 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curves for the detection of CAC in those with a total volume CAC score >0, >200, and >400. The SIF score was swept from 0.018 to 0.052 arbitrary units to generate each of the ROC curves, and the equal error rates (EERs) and associated SIF thresholds were as follows: for CAC volume score >0, EER = 0.31 at SIF = 0.029; for CAC volume score >200, EER = 0.24 at SIF = 0.033; and for CAC volume score >400, EER = 0.26 at SIF = 0.034. AUC, area under the curve. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/dia.

When looking at the severity of CAC, i.e., CAC score, SIF demonstrated a strong association with the most recent CAC score (r = 0.54, P < 0.0001), which remained even after adjusting for age (r = 0.38, P < 0.0001). In multivariable analysis allowing for age, sex, HbA1c, BMI, serum creatinine (renal function), AER (renal damage), HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, hypertension medication use, and a history of smoking, SIF still remained independently associated with the severity of CAC, i.e., the most recent CAC score (Table 2). Other independent correlates were age, CAD, AER, and a history of smoking.

Table 2.

Correlates of the Severity of CAC (Total Volume Score)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIF | 1.45 ± 0.22 (<0.0001) | 1.01 ± 0.24 (<0.0001) | 0.89 ± 0.23 (0.0002) | 0.56 ± 0.26 (0.03) |

| Age (years) | 0.92 ± 0.25 (0.0004) | 0.79 ± 0.25 (0.002) | 0.97 ± 0.25 (0.0002) | |

| Total CAD | 1.36 ± 0.49 (0.006) | 1.08 ± 0.49 (0.03) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.34 ± 0.21 (0.11) | |||

| (log) AER (μg/min) | 0.48 ± 0.24 (0.05) | |||

| History of smoking | 0.83 ± 0.45 (0.07) |

Data are mean ± SE values (P value).

Model 4, the stepwise selection model, allowed for the following variables: SIF, age, sex, CAD, HbA1c, BMI, ln-serum creatinine, ln-AER, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, use of hypertension medication, use of statins, and a history of smoking.

In subanalyses of the 80 participants who had previously undergone EBT scanning for CAC in 1996–1998 (CAC baseline), correlates of the progression of CAC (assessed between 2000 and 2007) were investigated. Table 3 demonstrates the relationship of SIF in the 20th year of the follow-up period with the progression of CAC (from the 12th year of follow-up to the 16th–18th year of follow-up) in the participants with any data on progression, those with a baseline CAC score of 0, and in those with a CAC score >0 at baseline, respectively. SIF was significantly associated with CAC progression (OR = 2.2, 1.09–4.45), even after allowing for age and baseline CAC score, serum creatinine, AER, and other univariately or clinically significant correlates (including BMI). Final multivariable correlates of CAC progression were SIF and baseline CAC score. In those with a baseline CAC score = 0, SIF was the only variable selected in the stepwise selection model, demonstrating a marginal association with CAC progression (P = 0.08). In those with a CAC score >0 at baseline, SIF was neither univariately nor multivariately associated with CAC progression. In the final multivariable model, only the baseline age was associated with the progression of CAC in those with a baseline CAC score greater >0.

Table 3.

Correlates of CAC Progression, Overall and After Stratification by Baseline CAC Score

| |

OR (95% confidence interval) for progression |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | In those with baseline CAC score > 0 | (Incidence) in those with baseline CAC score = 0 | |

| SIF | 2.20 (1.09–4.45) | NS | 2.42 (0.91–6.46) |

| Age (years) | N/S | 3.95 (1.00–15.54) | NS |

| Baseline CAC score | 3.02 (1.55–5.89) | NS | NA |

The stepwise selection model allowed for the following variables: SIF, age, baseline CAC score, sex, HbA1c, BMI, ln-serum creatinine, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, use of hypertension medication, and a history of smoking. NA, not applicable; NS, not selected.

Finally, age-adjusted SIF was significantly higher in those with a history of CAD (P = 0.01, data not shown). However, in the multivariable model (fully adjusted for age, sex, log-transformed [ln]-CAC, HbA1c, ln-AER, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, blood pressure medication use, BMI, and a history of smoking), SIF was not independently related to CAD, with only ln-CAC (OR = 1.28, P = 0.02) and ln-AER (OR = 1.34, P = 0.04) being associated. When the definition of CAD was restricted to myocardial infarction or revascularization (n = 20), only ln-CAC was significantly associated with CAD (OR = 2.00, P < 0.0001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document an association between SIF, a marker of skin collagen AGEs, and CAC. Increased levels of AGEs have been associated with arterial calcification of the coronary arteries in hemodialysis patients,15 with medial wall calcification of the internal thoracic artery of diabetes patients with CAD,28 and with medial wall calcification of the limbs of diabetes patients with neuropathy.29,30 In the current study we observed an age- and renal damage-independent relationship between SIF, a marker of AGEs, and the severity of calcification of the coronary arteries. We have also shown a relationship with the progression of CAC, independent of age and renal function (serum creatinine) and renal damage (AER). Finally, we have shown a strong association between SIF and CAC at clinically significant thresholds associated with CAD.

Putative mechanisms of vascular calcification include: calcium deposition into the arterial wall as a result of increased parathyroid hormone activity and elevated extraosseous calcium and phosphorus levels, as observed in kidney disease; vascular smooth muscle cell and calcifying vascular cell differentiation into osteoblastic cells; macrophage ingestion of elevated oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, which induces vascular smooth muscle cell migration from the media to intima layer and secretion of collagen fibers that trap calcium and apatite crystals; and effects of AGEs indirectly via low-density lipoprotein cholesterol or directly by inducing osteblastic differentiation of pericytes/vascular smooth muscle cells. We did not have measures of parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, or phosphorus levels and thus were unable to determine whether the relationship of SIF was independent of or interacted with that of calcium and phosphorus, although lipids, i.e., HDL cholesterol or non-HDL cholesterol, did not demonstrate a relationship with CAC nor did calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the 70% of participants with fasting data. Nevertheless, SIF, a marker of AGEs, was associated with the presence (univariately) and severity of CAC and demonstrated a marginal association in detecting those who had shown a progression in CAC.

AGEs have been shown to induce vascular calcification and to up-regulate mRNAs coding for markers of early- and late-phase osteoblastic differentiation. For example, Yamagishi et al.11 demonstrated that AGEs up-regulate osteoblastic differentiation of vascular pericytes. We have previously observed in this population a direct relationship between measures of abdominal adiposity and BMI and the prevalence of any CAC, but inverse relationships between these body fat indices and the severity of CAC, in those with CAC.31 In the current analyses, even after controlling for SIF, little relationship was seen between BMI in either the prevalence or the severity of CAC, which may reflect the smaller sample size assessed for SIF. In a previous report from our type 1 diabetes population we showed a strong relationship between radiographically determined medial wall calcification of the ankle and EBT-determined calcification of the coronary arteries.32 Sakata et al.28 observed higher levels of calcification of the medial wall of the internal thoracic artery in diabetes patients. In their population, internal thoracic calcification was associated with AGEs in those with diabetes but not in those without diabetes.

It is possible that the association between SIF and CAC is due to confounding by renal damage, as both increase with declining renal function and increasing renal damage, but our association with the severity of CAC was independent of renal function, i.e., serum creatinine, although not of renal damage, i.e., AER. In hemodialysis patients,15 independent of duration on dialysis, the fluorescent AGE, pentosidine, was associated with CAC.

CAC is a measure of atherosclerotic burden, and even medial wall CAC is associated with atherosclerotic disease. Rumberger et al.6 were able to use EBT-determined calcification to discriminate between ≥50% stenosis and no obstructive disease, but not the extent of stenosis, in 139 men and women. Higher levels of the soluble receptor for AGEs were cross-sectionally associated with cardiovascular disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes in the EURODIAB study.33 Skin autofluorescence, as detected by the AGE Reader™ (DiagnOptics BV, Gröningen, The Netherlands), has very recently been shown to predict cardiovascular events in a cohort of 973 subjects with type 2 diabetes.34 Although the relationship between SIF and clinical CAD, after accounting for CAC and renal damage, was not significant multivariably in our population, it is likely in this population that both CAC and renal damage are part of the mediating pathway between SIF and clinical CAD. Interestingly, AGEs have been postulated to play an etiologic role in diabetic nephropathy.35 Furthermore, it is quite possible that the association between SIF and CAD may have been underestimated in this partially survivor cohort because those with the greatest SIF may have already died with CAD and/or renal events.

The current results are of potential clinical significance in at least two ways. First, they may help more clearly define the specific role of hyperglycemia, and consequent AGE formation, in the pathogenesis of CAD in type I diabetes and thus facilitate disentangling this component from the multiple other factors at play, including standard risk factors and renal disease. Second, these results if confirmed by others, and in prospective studies, would suggest that periodic assessments of SIF may help identify those most prone to complications. Use of SIF may be more efficient than currently available cumulative HbA1c measures and for CAD, as indicated here, may be more feasible, cheaper, and safer than, for example, periodic CAC scanning. The optimal assessment of this approach will come from prospective studies that are currently underway.

As indicated, a major limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the study design. The calcification data were collected prior to our ability to measure SIF, so our results show only an association at best. However, as our major outcome in this study was CAC, which also shows a strong relationship with all-cause mortality,36 this cross-sectional association in living participants still has important implications. Further follow-up is planned to determine the association of SIF with future cardiovascular events and mortality.

A strength of this study was the use of SIF. Although the SCOUT DM has the unique ability to measure both skin autofluorescence and intrinsic fluorescence, intrinsic fluorescence is a more reliable measure of fluorescence across varying skin types and pigmentation because it compensates for optical absorption by hemoglobin and melanin in the emission region, whereas autofluorescence does not.

The relationship of this spectroscopically determined marker of AGEs with CAC appears stronger with more severe calcification. Given the strong relationship of CAC with CAD, and its even stronger relationship with mortality, our finding of a relationship of SIF with CAC, independent of age, a history of CAD, renal function, or renal damage has important implications. To what degree SIF and AGEs formation are truly causative in the pathways to CAC and CAD cannot be determined by observational data such as these alone. These data suggest that SIF may be a useful marker of CAC/CAD risk; however, further studies are needed to determine whether it is a potential therapeutic target. In conclusion, SIF shows a cross-sectional association with both CAC and recent progression of CAC in type 1 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant DK 34818 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors would also like to thank the participants of the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes study for their dedication and support and for making this work possible.

Author Disclosure Statement

N.M. and J.M. are employees of VeraLight, Inc., the manufacturer of the SCOUT DM used to determine skin intrinsic fluorescence levels in this study. B.C., D.E., and T.O. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Dabelea D. Kinney G. Snell-Bergeon JK. Hokanson JE. Eckel RH. Ehrlich J. Garg S. Hamman RF. Rewers M. Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes Study: Effect of type 1 diabetes on the gender difference in coronary artery calcificaion: a role for insulin resistance? The Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:2833–2839. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumberger JA. Brundage BH. Rader DJ. Kondos G. Electron-beam tomographic coronary calcium scanning: a review and guidelines for use in asymptomatic persons. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:243–252. doi: 10.4065/74.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson JC. Edmundowicz D. Becker DJ. Kuller LH. Orchard TJ. Coronary calcium in adults with type 1 diabetes: a stronger correlate of clinical coronary artery disease in men than in women. Diabetes. 2000;49:1571–1578. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arad Y. Spadaro LA. Goodman K. Newstein D. Guerci AD. Prediction of coronary events with electron-beam tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1253–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raggi P. Callister TQ. Cooil B. He ZX. Lippolis NJ. Russo DJ. Zelinger A. Mahmarian JJ. Identification of patients at increased risk of unheralded myocardial infarction by electron-beam computed tomography. Circulation. 2000;101:850–855. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumberger JA. Sheedy PF., 3rd Breen JF. Schwartz RS. Coronary calcium, as determined by electron beam computed tomography, and coronary disease on arteriogram. Circulation. 1995;91:1363–1367. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detrano R. Guerci AD. Carr JJ. Bild DE. Burke G. Folsom AR. Liu K. Shea S. Szklo M. Bluemke DA. O'Leary DH. Tracy R. Watson K. Wong ND. Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makita Z. Bucala R. Rayfield EJ. Friedman EA. Kaufman AM. Korbet SM. Barth RH. Winston JA. Fuh H. Manogue KR. Cermai A. Vlassara H. Reactive glycosylation endproducts in diabetic uraemia and treatment of renal failure. Lancet. 1994;343:1519–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92935-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawnay A. Millar DJ. The pathogenesis and consequenves of AGE formation in uraemia and its treatment. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1998;44:1081–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verzijl N. DeGroot J. Thorpe SR. Bank TA. Shaw JN. Lyons TJ. Bijlsma JW. Lafeber FP. Baynes JW. TeKoppele JM. Effect of collagen turnover on the accumulation of advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem. 2000;50:39027–39031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamagishi S. Fujimori H. Yonekura H. Tanaka N. Yamamoto H. Advanced glycation endproducts accelerate calcification in microvascular pericytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:353–357. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monnier VM. Bautista O. Kenny D. Sell DR. Fogarty J. Dahms W. Cleary PA. Lachin J. Genuth S. Skin collagen glycation, glycoxidation, crosslinking are lower in subjects with long-term intensive versus conventional therapy of type 1 diabetes: relevance of glycated collagen products versus HbA1c as markers of diabetic complications. DCCT Skin Collagen Ancillary Study Group. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1999;48:870–880. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meerwaldt R. Graaff R. Oomen PH. Links TP. Jager JJ. Alderson NL. Thorpe SR. Baynes JW. Gans RO. Smit AJ. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1324–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway B. Wang J. Ediger W. Orchard T. Skin fluorescence and type 1 diabetes: a new marker of complication risk [abstract] Diabetes. 2008;57(Suppl 11):A287. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taki K. Takayama F. Tsuruta Y. Niwa T. Oxidative stress, advanced glycation end product, and coronary artery calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;70:218–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makita Z. Radoff S. Rayfield EJ. Yang Z. Skolnik E. Delaney V. Friedman EA. Cerami A. Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end products in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:836–842. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109193251202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orchard TJ. Dorman JS. Maser RE. Becker DJ. Drash AL. Ellis J. LaPorte RE. Kuller LH. The prevalence of complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus by sex and duration: Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study II. Diabetes. 1990;39:1116–1124. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.9.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchard TJ. Dorman JS. Maser RE. Becker DJ. Ellis J. LaPorte RE. Kuller LH. Wolfson SK Jr. Drash AL. Factors associated with the avoidance of severe complications after 25 yr of IDDM: Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study I. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:741–747. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callister TQ. Cooil B. Raya SP. Lippolis NJ. Russo DJ. Raggi P. Coronary artery disease: improved reproducibility of calcium scoring with an electron-beam CT volumetric method. Radiology. 1998;208:807–814. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.3.9722864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warnick GR. Albers JJ. Heparin-Mn2+ quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol: an ultrafiltration procedure for lipemic samples. Clin Chem. 1978;24:900–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institutes of Health: Lipid Research Clinics Program. NIH publication number 75–628. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allain CC. Poon LS. Chan CS. Richmond W. Fu PC. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20:470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maynard JD. Rohrscheib M. Way JF. Nguyen CM. Ediger MN. Noninvasive type 2 diabetes screening: superior sensitivity to fasting plasma glucose and A1c. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1120–1124. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ediger MN. Olson BP. Maynard JD. Noninvasive optical screening for diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;4:776–780. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hull E. Ediger M. Unione A. Deemer E. Stroman M. Baynes J. Noninvasive, optical detection of diabetes: model studies with porcine skin. Opt Express. 2004;12:4496–4510. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.004496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hokanson JE. MacKenzie T. Kinney G. Snell-Bergeon JK. Dabelea D. Ehrlich J. Eckel RH. Rewers M. Evaluating changes in coronary artery calcium: an analytic method that accounts for interscan variability. AM J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1327–1332. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mooy JM. Grootenhuis PA. de Vries H. Kostense PJ. Popp-Sijders C. Bouter LM. Heine RJ. Intra-individual variation of glucose, specific insulin and proinsulin concentrations measured by two oral glucose tolerance tests in a general Caucasian population: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 1996;39:298–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00418345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakata N. Takeuchi K. Noda K. Keijrp S. Tachikawa Y. Tashiro T. Nagai R. Horiuchi S. Calcification of the medial layer of the internal thoracic artery in diabetic patients: relevance of glycoxidation. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:467–574. doi: 10.1159/000075807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edmonds ME. Morrison N. Laws JW. Watkins PJ. Medial arterial calcification and diabetic neuropathy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:928–930. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6320.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goebel FD. Füessl HS. Möckenberg's sclerosis after sympathetic denervation in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetologia. 1983;24:347–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00251822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conway B. Miller RG. Costacou T. Fried L. Kelsey S. Evans RW. Edmundowicz D. Orchard TJ. Double-edged relationship between adiposity and coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2007;4:332–339. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2007.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costacou T. Huskey ND. Edmundowicz D. Stolk R. Orchard TJ. Lower-extremity arterial calcification as a correlate of coronary artery calcification. Metabolism. 2006;55:1689–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nin JW. Ferreira I. Schalkwijk CG. Prins MH. Chaturvedi N. Fuller JH. Stehouwer CD. EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study Group: Levels of soluble receptor for AGE are cross-sectionally associated with cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes, and this association is partially mediated by endothelial and renal dysfunction and by low-grade inflammation: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:705–714. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutgers HL. Gerrits EG. Graaff R. Links TP. Sluiter WJ. Gans RO. Bilo HJ. Smit AJ. Skin autofluorescence provides additional information to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk score for the estimation of cardiovascular prognosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2009;52:789–797. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamagishi S. Nakamura K. Imaizumi T. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and diabetic vascular complications. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:93–106. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niskanen L. Sitonen O. Suhonen M. Uusitupa M. Medial artery calcification predicts cardiovascular mortality in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1252–1756. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.11.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]