Abstract

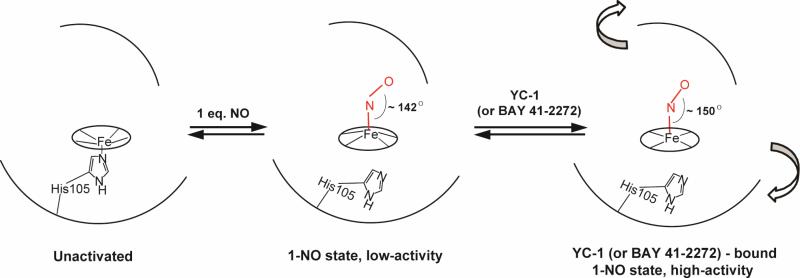

Modulation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) activity by nitric oxide (NO) involves two distinct steps. Low level activation of sGC is achieved by the stoichiometric binding of NO (1-NO) to the heme cofactor, while much higher activation is achieved by the binding of additional NO (xsNO) at a non-heme site. Addition of the allosteric activator YC-1 to the 1-NO form leads to activity comparable to xsNO state. In this study the mechanisms of sGC activation were investigated using electronic absorption and resonance Raman (RR) spectroscopic methods. RR spectroscopy confirmed that the 1-NO form contains 5-coordinate NO-heme and showed that the addition of NO to the 1-NO form has no significant effect on the spectrum. In contrast, addition of YC-1 to either the 1-NO or xsNO forms alters the RR spectrum significantly, indicating a protein-induced change in the heme geometry. This change in the heme geometry was also observed when BAY 41-2272 was added to the xsNO form. Bands assigned to bending and stretching motions of the vinyl and propionate substituents change intensity in a pattern suggesting altered tilting of the pyrrole rings to which they are attached. In addition, the N-O stretching frequency increases, with no change in the Fe-NO frequency, an effect modeled via DFT calculations as resulting from a small opening of the Fe-N-O angle. These spectral differences demonstrate different mechanisms of activation by synthetic activators, such as YC-1 and BAY 41-2272, and excess NO.

Introduction

The gaseous signaling molecule nitric oxide (NO) powerfully modulates a large range of physiological responses (1-3). In eukaryotes NO signaling is transduced by the hemoprotein soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) (4) which generates the second messenger cyclic GMP (cGMP) at a rate that is strongly up-regulated by NO. cGMP in turn regulates a host of other enzymes including phosphodiesterases, cGMP-gated ion channels, and cGMP-regulated protein kinases (4, 5).

sGC is a heterodimer consisting of two homologous subunits, α1 and β1. The β1 subunit contains the heme cofactor present within a Heme Nitric oxide - OXygen binding (H-NOX) domain (6). This domain has been localized to the N-terminal ~200 residues of the β1 subunit and is a conserved heme-binding domain found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (7). NO has long been known to bind the heme prosthetic group of sGC, forming a transient 6-coordinate adduct, which then dissociates the proximal histidine ligand, leaving 5-coordinate NO-heme (8, 9). Formation of the 5-coordinate NO complex has been shown to coincide with increased enzyme activity, suggesting that the histidine dissociation is an integral step in sGC regulation by NO (9-11). However, it has recently been shown that the Fe-NO adduct formed in the presence of stoichiometric NO (1-NO) is activated only modestly from the basal enzyme rate, while the Fe-NO adduct formed in the presence of excess NO (xsNO) exhibits high activity (12, 13). Experiments done with methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) suggest that this second NO binding event involves one or more cysteine residues (14). Additionally, the high activity state is transient, and persists under anaerobic conditions, suggesting that the activating species is not a nitrosothiol, but possibly a direct adduct of NO with thiol (14).

The low-activity 1-NO adduct can be further activated by the allosteric activator YC-1 (5-[1-(phenylmethyl)-1H-indazol-3-yl]-2-furanmethanol) (13, 15). YC-1 was discovered in a pharmaceutical screen searching for molecules that would increase cGMP levels in the cellular lysate (16). Following characterization of YC-1 activation of sGC, BAY 41-2272 (5-cyclopropyl-2-{1-(2-fluorobenzyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-3-yl}pyrimidin-4-ylamine) was synthesized in an effort to improve the solubility and efficacy of YC-1 (17). Both compounds weakly activate unligated sGC and synergistically activate the carbon monoxide (CO)- and NO-bound forms of the enzyme (4, 18). Additionally, YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 lead to similar changes in the EPR and RR spectra of the sGC-NO complex (19), indicating that they induce a similar structural change in the protein and likely bind to the same site. While the exact binding site of these molecules is unknown, there is evidence that they bind to the N-terminus of the α1 subunit (20). To date, no endogenously produced sGC activators have been found; however, it remains an intriguing possibility that there may be endogenous small molecules that mediate CO, as well as NO signaling.

In this report electronic absorption and resonance Raman (RR) spectroscopic methods have been used to detect changes in the heme environment when the activators are added to sGC. The spectra establish that the proximal His ligand dissociates from the heme in the 1-NO adduct, and that the addition of excess NO to the 1-NO adduct has no further effect on the heme structure. This observation indicates that the molecular events that increase cGMP synthesis in response to excess NO do not directly involve the heme. In contrast YC-1 does cause changes in the heme environment of both the 1-NO and xsNO adducts. While the NO complex remains 5-coordinate, intensity changes of RR bands associated with the heme vinyl and propionate substituents, together with a shift in a porphyrin vibrational frequency, suggest alterations in the heme out-of-plane distortion. In addition, the N-O stretching frequency shifts in a direction that suggests the Fe-N-O angle opens upon YC-1 binding. These effects point to protein-induced heme alteration associated with YC-1 binding, whose mechanism of activation is clearly different from that of xsNO. Thus sGC has alternative routes for achieving high activity levels.

Experimental Details

Protein expression, purification and activity assay

Rat sGC α1β1 was purified as described previously (21). Rat β1(1-194) and β1(1-385) were purified according to a previously published protocol (22). The β1(1-194) mutants Pro118Ala (P118A) and Ile145Tyr (I145Y) were generated and purified by a method that will be described elsewhere. Additionally, β1(1-194) P118A was purified without heme and reconstituted according to a method that will be described elsewhere.

The 1-NO and xsNO sGC forms were assayed in the presence and absence of YC-1 (Cayman Chemical) at a final concentration of 150 μM. The 1-NO form was made by adding 50 μM DEA/NO to the protein and then removing excess NO by 3 cycles of dilution/concentration using a 10 K Ultrafree-0.5 centrifugal filter device (Millipore) into 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT (19). Electronic absorption spectra of the samples were collected before each assay. Duplicate end-point assays were then initiated by addition of 3 mM MgCl2 and 1.5 mM GTP at 25 °C. Samples were quenched after 3 min by the addition of 400 μL of 125 mM Zn(CH3CO2)2 and 500 μL of 125 mM Na2CO3. cGMP was quantified using a cGMP enzyme immunoassay kit, Format B (Biomol), per the manufacturer's instructions. All experiments were repeated 2-3 times to ensure reproducibility.

Resonance Raman and electronic absorption spectroscopies

The xsNO sGC adduct for resonance Raman and electronic absorption studies was prepared by adding, anaerobically, 14NO (or 15NO) saturated buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) into ligand-free sGC in argon atmosphere. The final NO concentration was ~ 150 μM. The 1-NO sGC adduct was prepared from the excess NO bound sample by performing three cycles of dilution/concentration with NO-free buffer using a 10 K Ultrafree-0.5 centrifugal filter device (Millipore). YC-1 or BAY 41-2272 bound samples were prepared by adding stock solutions (in DMSO) of respective effectors anaerobically into the NO bound sample. The final YC-1 concentration was 100-150 μM (~ 2 % [v/v] DMSO). The final concentration of BAY 41-2272 (Sigma) was 15 μM (~ 2 % [v/v] DMSO). The final protein concentration was 4-10 μM.

RR spectra were collected via back-scattering geometry at room temperature. The excitation wavelength at 400 nm was obtained by frequency doubling, using a nonlinear lithium triborate crystal, of a Ti:sapphire laser (Photonics International TU-UV), which was pumped by the second harmonic of a Q-switched Nd:YLF laser (Photonics Industries International, GM-30-527). Laser power at the sample was kept to a minimum (less than 1 mW) by using a cylindrical lens to avoid the photolysis of bound NO. Scattered light was collected and focused onto a single spectrograph (SPEX 1269, 3600 grooves/mm) equipped with a CCD detector (Roper Scientific) operating at –110 °C. Spectra were calibrated with dimethyl formamide and DMSO and analyzed by Grams A/I software (Thermo-Galactic). UV-visible spectra were recorded on the Agilent 8453 UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) and processed using Grams A/I software.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

DFT calculations on the 5-coordinate Fe(II)NO porphine model complex were performed using the Gaussian 03 program (23). The standard 6-31G* basis set was used for all the atoms except Fe, for which Ahlrichs’ valence triple-ζ (VTZ) basis set was chosen (24). All calculations were performed assuming a doublet ground state. The unrestricted non-hybrid DFT functional, UBLYP, was employed, with an ultrafine integration grid. The structures with the fixed FeNO angle at specific values were optimized using tight convergence criteria and Cs symmetry constraints, which kept the NO ligand in the plane bisecting the Fe-N(pyrrole) bonds. Vibrational frequencies were then calculated and taken directly from the Gaussian program without scaling.

Results

NO adduct spectra

Full-length sGC and N-terminal truncations of the β1 subunit [β1(1-385) and β1(1-194)] were used in this study (Figure 1). The domain structure of sGC is illustrated in Figure 1. The β1(1-194) truncation contains the H-NOX domain with the heme ligated by His105 (22). β1(1-385) contains the H-NOX, PAS and part of the CC (coiled-coil) domains (25). β1(1-385) forms a homodimer (26), and β1(1-194) is a monomer (22). Three homologous bacterial H-NOX domain structures have been published (7, 27-29), and Figure 2 shows a homology model for the sGC H-NOX domain based on the Tt H-NOX structure (7). We examined the effect of residue substitution in the putative distal heme-binding pocket, I145Y, and in the putative proximal heme-binding pocket, P118A (Figure 2), on NO binding to β1(1-194).

Figure 1.

(a) Domain structure of sGC (adapted from (4)). (b) Structure of YC-1.

Figure 2.

Homology model of sGC β1 H-NOX domain (based on Tt H-NOX structure, pdB: 1U55).

All wild-type (WT) and β1 mutants contained 5-coordinate Fe(II) heme, as evidenced by Soret absorption bands at ~430 nm (Figure 3, only full-length WT sGC spectra are shown), and νFe-His RR bands at 205-215 cm-1 (not shown). NO binding induced the breakage of the proximal Fe-His bond, producing 5-coordinate NO-heme, with ~400 nm Soret absorption bands (Figure 3) and ~520 and ~1680 cm-1 RR bands (Figures 4 and 5). These RR bands are associated with Fe-NO and N-O stretching vibrations of the bound NO and are sensitive to NO isotope substitution (see 14NO-15NO difference spectra, Figure 4). As discussed elsewhere (30), the ~520 cm-1 vibration is actually a mixture of Fe-N stretching and Fe-N-O bending coordinates, resulting from the bent Fe-N-O geometry. However, this mode responds to changes in backbonding similar to the Fe-CO stretching vibrations of corresponding CO adducts (30), and is designated as νFeN for simplicity.

Figure 3.

UV-visible spectra of ligand-free (black), NO bound (blue) and NO + YC-1 bound (red) full-length WT sGC. Effect of 1-NO (top panel) and xsNO (bottom panel) binding are shown. Absorption at 326 nm is due to YC-1.

Figure 4.

400 nm – excited RR spectra of full-length WT sGC containing one NO (1-NO), excess NO (xsNO), and the 14NO-15NO difference bands (in black), and with added YC-1 (in red). Band assignments and frequencies are indicated. Full spectra are given in Figure S1.

Figure 5.

400 nm – excited RR spectra of WT β1(1-194) with excess NO (xsNO) and of the P118A and I145Y variants. The 14NO-15NO difference bands are shown.

1-NO and xsNO adducts

sGC activity associated with NO bound only at the heme (1-NO) and excess NO (xsNO) is shown in Table 1. Excess NO can be removed by dialysis, allowing spectral comparison of the two forms, 1-NO and xsNO. The electronic absorption spectra were the same for the 1-NO and xsNO forms as expected based on previous results (Figure 3) (12, 21). There is a small fraction of unligated protein present in the 1-NO sample as indicated by the shoulder at ~ 430 nm (Figure 3), and also by the 1358 cm-1 ν4 RR band (Figure S1). The RR spectra of the 1-NO and xsNO adducts were essentially identical (Figure 4 and Figure S1). The νNO band was found at the same frequency, 1680 cm-1, in the 1-NO and xsNO spectra, while the νFeN frequency was slightly higher, 522 vs 521 cm-1, in the xsNO spectrum (Figure 4, Table 2). The porphyrin vibrations were all at the expected positions for 5-coordinate NO-heme (8, 31), and the same in both spectra. The close similarity of the 1-NO and xsNO RR spectra establishes that binding of additional NO produced no significant structural alteration in the heme.

Table 1.

Activation of sGC by heme-bound NO (1-NO), additional NO (xsNO), and by YC-1

| sGC State | Specific Activitya (nmol/min/mg) |

Fold Activation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -YC-1 | +YC-1 | -YC-1 | +YC-1 | |

| Basal | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 37 ± 11 | 1 | 4.4 |

| 1-NO | 46 ± 2.3 | 325 ± 25 | 5.5 | 39 |

| xsNO | 1227 ± 375 | 1679 ± 536 | 146 | 200 |

determined in duplicate at 25 °C.

Table 2.

Iron-ligand stretching frequencies (cm-1) for various full-length and H-NOX domain sGC-NO complexes

| sGC variants | Ligation | νFeN (cm-1) |

νNO (cm-1) |

ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -YC-1 | +YC-1 | -YC-1 | +YC-1 | |||

| Full-length WT | xs-NO | 525 | 1677 | (52) | ||

| xs-NO | 521 | 521a | 1681 | 1700a | (51) | |

| xs-NO | 522 | 521 | 1680 | 1687 | t.w.b | |

| 1-NO | 521 | 521 | 1680 | 1688 | t.w. | |

| β1(1-194) WT | xs-NO | 526 | 1677 | (22) | ||

| xs-NO | 523 | 1675 | t.w. | |||

| β1(1-194) P118A | xs-NO | 523 | 1675 | t.w. | ||

| β1(1-194) I145Y | xs-NO | 523 | 1675 | t.w. | ||

| β1(1-385) WT | xs-NO | 526 | 1676 | (25, 53) | ||

| xs-NO | 522 | 522 | 1677 | 1677 | t.w. | |

| 1-NO | 522 | 1677 | t.w. | |||

In the presence of GTP and MgCl2 (ref (51) ).

this work.

A subtle difference in the low-temperature EPR spectrum has been observed between 1-NO and xs-NO samples, indicating that the NO-heme does sense the protein alteration induced by the additional NO interaction (19). However, this influence is not sufficient to alter the heme-NO vibrations significantly.

Effects of YC-1 binding

The effector molecule YC-1 increases the basal activity of sGC ~4-fold, but enhances the activity of the 1-NO adduct much more, to ~40-fold above the basal level (Table 1). In contrast, the effect of YC-1 on the activity of the xsNO adduct is small. The effect of YC-1 on the RR spectrum of the sGC-NO complex has not been thoroughly examined. Here, we find that the RR spectra of both the 1-NO and xsNO sGC adducts exhibit the following significant spectral changes with YC-1 addition (Figure 4 insets):

In both cases, the νNO band shifts from ~1680 to ~1687 cm-1; the νFeN band remains the same (521 cm-1) for the 1-NO adduct, and shifts back to 521 cm-1 for the xsNO adduct (Figure 4, Table 2).

The porphyrin ν10 band at ~ 1645 cm-1 shifts up 3 cm-1 with YC-1 addition. This mode is sensitive to the heme geometry, and an upshift suggests reduction in the out-of-plane distortion of the 5-coordinate heme-NO (32, 33).

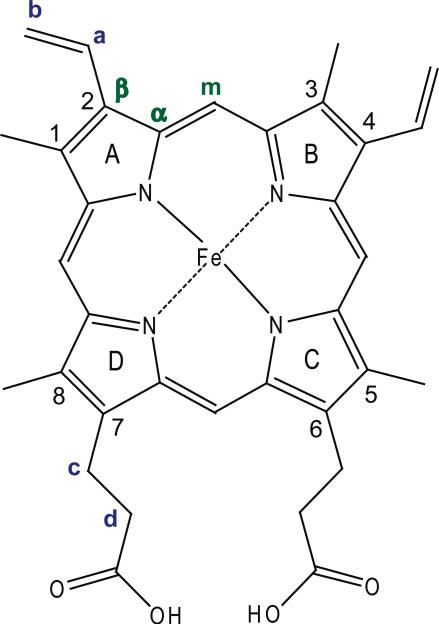

YC-1 also induces intensity changes of RR bands associated with the 2- and 4-vinyl substituents on the heme (see Figure 6 for labeling scheme), and also with a propionate bending mode at 369 cm-1 (34). There is a significant increase in intensity of the 397 cm-1 band, assigned to bending of the 4-vinyl group, but intensity loss of the 422 cm-1 band, assigned to bending of the 2-vinyl group (34). At the same time, bands assignable to the vinyl C=C stretches, at 1607 and the 1633 cm-1 (34), gain and lose intensity, and the 1607 cm-1 band shifts up to 1611 cm-1. The parallel with the 397/422 cm-1 intensity pattern suggests assignment of the 1607/1633 cm-1 pair to the 4- and 2-vinyl groups, respectively. The νC=C frequencies depend on the orientation of the vinyl groups relative to the pyrrole rings to which they are attached, in-plane orientations producing low values (35). The observed frequencies indicate that the 4-vinyl group lies in the plane of the pyrrole B ring (Figure 6), and rotates slightly out of the plane with YC-1 addition. The 2-vinyl group is positioned out of the plane of the A ring, in the presence and absence of YC-1.

Figure 6.

Labeling scheme for iron protoporphyrin-IX (heme). Pyrrole Cα and Cβ positions, as well as porphyrin Cm positions are shown in green, while vinyl Ca, Cb, and propionate Cc, Cd positions are shown in blue.

Increased RR intensity in the 4-vinyl modes implies increased resonance enhancement, reflecting greater displacement of the vibrational coordinates in the resonant π-π* excited state. This could result from the rotation of the 4-vinyl group toward the porphyrin plane, or from the reduction in the degree of pyrrole tilting out of the porphyrin plane. The former mechanism is excluded if the 4-vinyl group starts out with an in-plane orientation, as inferred from the low νC=C frequency. Thus we propose that pyrrole tilting is the mechanism of intensity modulation, and that the vinyl mode intensity pattern reflects pyrrole tilting toward and away from the porphyrin plane for rings B and A, respectively, to which the 4- and 2-vinyl groups are attached. Likewise intensification of the 369 cm-1 propionate bending band likely involves tilting of pyrrole rings C and/or D toward the porphyrin plane. Additionally, the ν10 upshift indicates that the net out-of-plane displacement is reduced upon YC-1 addition. A similar RR spectrum was observed when BAY 41-2272 was added to the xsNO adduct (data not shown).

In summary, the binding of excess NO to sGC perturbs the heme minimally, but YC-1 binding produces the same significant structural changes in the heme conformation for both the 1-NO and xsNO adducts.

β1(1-194) and β1(1-385)

RR spectra were also characterized for WT β1(1-194) (Figure 1), and for two mutants, P118A and I145Y (Figure 2). P118A was introduced to relieve non-bonded forces thought to be responsible for heme distortion in the homologous Tt H-NOX domain (36), while I145Y was introduced to test the effect of a potential H-bond donor to heme-bound ligands. The RR spectra of the NO adducts of the β1(1-194) mutants (Figure 5) were similar to the RR spectrum of the full-length sGC Fe(II)-NO complex, except for slight up- and downshifts of νFeN and νNO, from 521 to 523 cm-1 and from 1680 to 1675 cm-1, respectively (Table 2). Neither the P118A nor I145Y residue substitution had any effect on the Fe(II)-NO RR spectra.

A similar RR spectrum was observed for β1(1-385) (Figure S2, Table 2) which contains the PAS domain, and part of the coiled-coil domain, as well as the H-NOX domain (Figure 1). The minor variations observed were in νFeN and νNO, which had intermediate values, 522 and 1677 cm-1, respectively, between the values observed for full-length sGC and β1(1-194).

FeNO angle dependence from DFT computation

To investigate the origin of the YC-1-induced upshift of νNO, we used density functional theory (DFT) to analyze the Fe-N-O angle dependence of the vibrational frequencies. A previous computation from our laboratory (37) had indicated that opening the Fe-N-O angle from its optimum value would elevate νNO with little effect on νFeN. We have revisited this computation, using a different density function method (BLYP instead of B3LYP), which was subsequently shown to give improved results for NO-heme adducts (30). Table 3 lists bond distances, vibrational frequencies and relative energies for the model complex (NO)Fe(II)P (P = porphine), when the Fe-N-O angle was constrained to a range of values around the optimum, 142°. Figure 7 plots the computed frequencies and energies. Since the constrained structures are not at potential energy minima, the computed frequencies are not strictly correct, but the errors are small. However, DFT-computed frequencies are generally higher than experimentally observed ones due to systematic errors and to neglect of anharmonicity and solvent effects. Computed frequencies can generally be brought into agreement with experimental frequencies by empirical scaling of force constants associated with specific bond types (38-40). The νFeN and νNO frequencies computed for the optimum angle, 142.4°, can be brought into agreement with the values observed for the sGC-NO complex using scale factors of 0.997 for N–O and 0.870 for Fe–N. The former value is in the range generally found with BLYP functional for bonds between first-row atoms (40). For metal-ligand bonds, scaling factors have not been systematically analyzed, although in a Hartree-Fock study of metal-oxo stretches a scaling factor of 0.86 was obtained for first row transition metals (41).

Table 3.

DFT (BLYP) structural parameters (Å), vibrational frequencies (cm-1), and energies (kcal/mol) calculated for the 5-c Fe(II)P-NO Cs model under varying FeNO angle

| Fe-NO | N-O | Fe-Np | ν Fe-N | ν N-O | neg. freq. | ΔE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120° | 1.7883 | 1.2065 | 2.010/2.036 | 1601 | 468 | – | 5.166 |

| 125° | 1.7641 | 1.2038 | 2.010/2.038 | 1621 | 512 | – | 3.093 |

| 130° | 1.7456 | 1.2014 | 2.011/2.040 | 1639 | 551 | – | 1.536 |

| 135° | 1.7313 | 1.1990 | 2.012/2.042 | 1658 | 578 | – | 0.530 |

| 140° | 1.7203 | 1.1969 | 2.014/2.043 | 1677 | 594 | – | 0.055 |

| 142.4° | 1.7159 | 1.1959 | 2.016/2.044 | 1686 | 599 | – | 0.000 |

| 145° | 1.7121 | 1.1948 | 2.017/2.044 | 1695 | 602 | – | 0.058 |

| 150° | 1.7058 | 1.1932 | 2.020/2.046 | 1710 | 602 | -59 | 0.468 |

| 155° | 1.7009 | 1.1917 | 2.023/2.047 | 1724 | 599 | -103 | 1.200 |

| 160° | 1.6985 | 1.1902 | 2.027/2.048 | 1738 | 591 | -147 | 2.142 |

| 165° | 1.6970 | 1.1889 | 2.032/2.049 | 1749 | 582 | -71/-187 | 3.154 |

| 170° | 1.6966 | 1.1879 | 2.037/2.049 | 1759 | 573 | -158/-218 | 4.067 |

| 175° | 1.6972 | 1.1872 | 2.042/2.048 | 1766 | 565 | -223/-238 | 4.703 |

| 180° | 1.6972 | 1.1870 | 2.045/2.045 | 1768 | 562 | -244/-244 | 4.933 |

Figure 7.

Computed frequencies for (NO)Fe(II)P when the FeNO angle was constrained at the indicated values. The equilibrium angle is 142°. The inset shows computed energies associated with the angle constraints.

The bending potential (Figure 7, inset) is fairly shallow. Opening or closing the Fe-N-O angle by 10° from the optimum decreases the energy (ΔE) by only ~ 1 kcal/mol. The bond distances vary monotonically with the Fe-N-O angle (Table 3). Specifically, as the angle opens up and approaches 180°, the Fe-N and N-O distances both decrease, reflecting the strengthening of the Fe-N and N-O bonds expected from Fe-NO backbonding. Consistent with this interpretation, the computed Mulliken charge on the O atom becomes steadily more negative, while the charge on the Fe becomes steadily more positive as the angle increases (Table S1).

The νFeN and νNO frequencies likewise vary in concert for small angles (Figure 7), but as the angle exceeds the optimum value, νFeN levels off, and begins to decline. The reason for this effect is that the effective mass of the NO group increases as the angle increases. At 180°, the effective mass is the full NO mass, while at 90° it is only the mass of the N atom. This kinematic effect counters the force constant trend associated with decreasing Fe-N distance (37).

Discussion

An essential finding of this study is that YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 significantly impact the heme structure of sGC-NO, whereas excess NO does not, even though both serve to up-regulate the relatively low activity of the sGC 1-NO adduct.

The YC-1 effect on structure is evident in RR band intensity changes associated with the vinyl and propionate peripheral substituents on the heme. The changes suggest alterations in the degree of tilting of the pyrrole rings to which these substituents are attached. In addition, a YC-1-induced upshift of the conformation-sensitive ν10 band indicates that the net out-of-plane heme distortion is lessened.

The crystal structure of the Tt H-NOX domain, which is homologous to the heme-binding domain of sGC, reveals that the protein contains a highly distorted heme, with >2 Å deviations of some atoms from the average plane, brought about by a combination of ruffling and saddling distortions (7). The heme is held between distal and proximal sub-domains of the protein. The crystal structure also revealed rotation of the two sub-domains by ~11° between the two molecules in the unit cell. Moreover, replacement with Ala of a single residue, Pro115 (Tt H-NOX numbering), whose non-bonded contact with pyrrole ring D was predicted to be important in the distortion, resulted in significant relaxation of the heme, and displacement of the N-terminal (distal) sub-domain of the protein (36). These results suggest that the coupling of heme distortion with segmental protein motion may be integral to the signaling mechanism in Tt H-NOX, and, by extension, in sGC.

Tran et al. reported that the heme relaxation in the P115A variant of Tt H-NOX was detectable in solution RR spectra (42). ν10 shifted to a higher frequency, as expected, and reduced intensity was observed for a number of bands in the 500-1000 cm-1 region, associated with pyrrole folding and methane C-H out-of-plane modes. However, we found that mutation of the homologous proline to Ala in β1(1-194) (Pro 118 in the rat β1 numbering system) had no effect on the RR spectrum of the sGC Fe(II)-NO complex. Likewise mutation of Ile 145 to Tyr, which introduces a Tyr into the heme distal pocket, was without effect. An sGC homology model based on Tt H-NOX places β1 Ile 145 in the same place as Tyr 140 in Tt H-NOX. In Tt H-NOX Tyr 140 provides a stabilizing H-bond to the bound O2. Mutation of Ile 145 to Tyr in β1(1-385) enables the protein to bind O2, suggesting that the tyrosine interacts with the heme ligand (43). The results here suggests that Tyr 145 in β1(1-194) is not in an optimal position for H-bonding to the bound NO; however, kinetic studies comparing the interaction of NO, CO and O2 with β1(1-194), β1(1-385) and full-length sGC I145Y mutants will be important for evaluating the H-bonding capabilities of Tyr 145 in the different proteins.

Although YC-1 induces a ν10 upshift in the sGC-NO RR spectrum, like the O2-bound P115A substitution in Tt H-NOX, the other spectral changes are quite different in the two cases. The striking vinyl and propionate mode intensity changes induced by YC-1 are not seen in the Tt H-NOX P115A variant (42). Thus, simple relaxation of the heme geometry does not account for the YC-1 effect. Rather there is an enforced geometry change, mediated by the peripheral substituents.

We note that YC-1 or BAY 41-2272 binding to the CO adduct of sGC also induces high-level of enzyme activity. Effects of YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 on CO adduct RR spectra have been documented in several studies (44-47) and very similar vinyl and propionate RR mode changes to those observed here for the NO adduct have recently been reported (48, 49). Thus, YC-1 and BAY 41-2272 are seen to activate both the NO and CO adducts by the same allosteric mechanism, which enforces pyrrole rotation and planarization of the heme.

An enforced geometry change is also indicated by the YC-1-induced upshift in νNO. We interpret this shift as resulting from an opening of the FeNO angle, based on our DFT analysis. The primary determinant of the νFeN and νNO frequencies is backbonding from Fe to NO. Increasing the backbonding, through inductive or electrostatic effects, increases νFeN while decreasing νNO. The resulting anticorrelation of the two frequencies is shown in Figure 8, in which the solid line represents the best fit to a series of 5-coordinate (NO)Fe(II)TPP-X complexes, based on tetraphenylporphine with variable electron donating and withdrawing groups on the phenyl rings (50). The NO adducts of sGC are seen to fall on this line, but YC-1 moves the points off the line. An even larger deviation, in the same direction, is seen when GTP is added to sGC-NO complex (Figure 8). GTP has been reported to shift νNO to 1700 cm-1, again with no change in νFeN (51). In the previously published spectrum (51), one can see vinyl and propionate mode intensity changes similar to those we observe in the presence of YC-1 or BAY 41-2272. GTP is both a substrate and allosteric modulator of sGC, and preincubation of sGC with GTP converts the low-activity 1-NO form to a high activity sGC state (12).

Figure 8.

νFeN/νNO data for Fe(II)NO adducts of full-length (●) and truncated (○) wild-type sGC. The solid line is the correlation obtained from a series of 5-coordinate (NO)Fe(II)TPP-X complexes (50).

Our DFT analysis shows that opening the angle beyond its optimum of 142° increases νNO with little change in νFeN, because of countervailing force field and kinematic influences. According to Figure 7 and Table 3, opening the angle from 142 to 150° is expected to increase νNO by 24 cm-1, the effect seen for GTP addition, while increasing νFeN by only 3 cm-1. The energy required for this opening is small, 0.5 kcal/mol, and could be provided by non-bonded contacts with distal residues in the heme pocket when the protein undergoes a conformational change.

In summary, YC-1, BAY 41-2272 and GTP binding are inferred to induce protein conformational changes that alter the heme pocket, as illustrated in Figure 9. These changes enforce a slight opening of the FeNO angle, and also pyrrole rotations leading to net planarization of the porphyrin, through peripheral non-bonded contacts with the vinyl and propionate substituents. We envision the conformational change as involving an activity-inducing rotation of the distal and proximal halves of the H-NOX domain.

Figure 9.

Structural model for activation-linked transitions of sGC-NO. Binding of NO to the heme breaks the proximal Fe-His bond, and induces porphyrin distortion via protein contacts. sGC exhibits a low level of activity in this state. Effector binding (YC-1 or BAY 41-2272) is suggested to induce an activating rotation of the two halves of the H-NOX domain, which alters the heme-protein contacts. In the altered conformation the Fe-NO angle is opened and pyrrole rings are rotated, producing net planarization of the heme. Binding of additional NO to the 1-NO adduct also induces high activity via an alternative mechanism that does not affect the heme-NO structure.

These structural changes are not seen when excess NO is bound to sGC. There are no changes in the RR spectrum of the xsNO sGC adduct, relative to the 1-NO adduct, except for a very small upshift in νFeN. Thus the profound effect of excess NO on enzyme activity is not accompanied by a significant alteration of the heme structure. Both YC-1 and excess NO produce major enhancements of the enzymatic rate, but the conformational changes underlying activation are clearly different.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- NO

nitric oxide

- 1-NO

stoichiometric binding of NO

- xsNO

excess NO binding

- CO

carbon monoxide

- YC-1

3-(5'-hydroxy-methyl-3'-furyl)-1-benzylindazole

- RR

resonance Raman

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine 3',5'-monophosphate

- BAY 41-2272

5-cyclopropyl-2-{1-(2-fluorobenzyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-3-yl}pyrimidin-4-ylamine

- H-NOX

Heme-Nitric oxide/OXygen binding

- Tt

Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GTP

guanosine 5'-triphosphate

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- Ti:sapphire

titanium sapphire

- Nd:YLF

neodymium doped yttrium lithium fluoride

- CCD

charge coupled device

- WT

wild type

- 6-c

six-coordinate

- 5-c

five-coordinate

- DFT

density functional theory

Footnotes

This work was supported financially by NIH grants GM033576 (TGS) and GM077365 (MAM)

Supporting Information Available. Complete reference 23; Mulliken charges calculated for 5-coordinate (NO)Fe(II)P under varying Fe-NO angle; RR spectra of full-length WT sGC containing one NO (1-NO), excess NO (xsNO), and the 14NO-15NO difference bands, covering the ν4 and ν7 regions; RR spectra of β1(1-385) in the presence of 1-NO, xsNO and YC-1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Butler AR, Williams DLH. The physiological role of nitric oxide. Chemical Society Review. 1993;22:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuteja N, Chandra M, Tuteja R, Misra MK. Nitric oxide as a unique bioactive signaling messenger in physiology and pathophysiology. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2004;4:227–237. doi: 10.1155/S1110724304402034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bian K, Murad F. Nitric oxide (NO) -- Biogeneration, regulation, and relevance to human diseases. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2003;8:d264–d278. doi: 10.2741/997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. Biochemistry of soluble guanylate cyclase. In: Schmidt HHHW, Hofmann F, Stasch J-P, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kots AY, Martin E, Sharina IG, Murad F. A short history of cGMP, guanylyl cyclases, and cGMP-dependent protein kinases. In: Schmidt HHHW, Hofmann F, Stasch J-P, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boon EM, Marletta MA. Ligand discrimination in soluble guanylate cyclase and the H-NOX family of heme sensor proteins. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2005;9:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellicena P, Karow DS, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of an oxygen-binding heme domain related to soluble guanylate cyclases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:12854–12859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405188101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu AE, Hu S, Spiro TG, Burstyn JN. Resonance Raman spectroscopy of soluble guanylyl cyclase reveals displacement of distal and proximal heme ligands by NO. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994;116:4117–4118. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone JR, Marletta MA. Spectral and kinetic studies on the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1093–1099. doi: 10.1021/bi9519718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wedel B, Humbert P, Harteneck C, Foerster J, Malkewitz J, Bohme E, Schultz G, Koesling D. Mutation of His-105 in the β1 subunit yields a nitric oxide-insensitive form of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:2592–2596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dierks EA, Hu S, Yu A, Spiro TG, Burstyn JN. Demonstration of the role of scission of the proximal histidine-iron bond in the activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase through metalloporphyrin substitution studies. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:7316–7323. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russwurm M, Koesling D. NO activation of guanylyl cyclase. EMBO Journal. 2004;23:4443–4450. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cary SPL, Winger JA, Marletta MA. Tonic and acute nitric oxide signaling through soluble guanylate cyclase is mediated by nonheme nitric oxide, ATP, and GTP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:13064–13069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506289102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernhoff NB, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. A nitric oxide/cysteine interaction mediates the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:21602–21607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911083106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cary SPL, Winger JA, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. Nitric oxide signaling: no longer simply on or off. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2006;31:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko FN, Wu CC, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM. YC-1, a novel activator of platelet guanylate cyclase. Blood. 1994;84:4226–4233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straub A, Stasch J-P, Alonson-Alija C, Benet-Buchholz J, Ducke B, Feurer A, Fürstner C. NO-Independent stimulators of soluble guanylate cyclase. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2001;11:781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stasch J-P, Hobbs AJ. NO-independent, heme-dependent soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators. In: Schmidt HHHW, Hofmann F, Stasch J-P, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 277–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derbyshire ER, Gunn A, Ibrahim M, Spiro TG, Britt RD, Marletta MA. Characterization of two different five-coordinate soluble guanylate cyclase ferrous–nitrosyl complexes. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3892–3899. doi: 10.1021/bi7022943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stasch JP, Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Dembowsky K, Feurer A, Gerzer R, Minuth T, Perzborn E, Pleiss U, Schroder H, Schroeder W, Stahl E, Steinke W, Straub A, Schramm M. NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature. 2001;410:212–215. doi: 10.1038/35065611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winger JA, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. Dissociation of nitric oxide from soluble guanylate cyclase and heme-nitric oxide/oxygen binding domain constructs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:897–907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karow DS, Pan D, Davis JH, Behrends S, Mathies RA, Marletta MA. Characterization of functional heme domains from soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16266–16274. doi: 10.1021/bi051601b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03, Revision E.01 ed. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauernschmitt R, Ahlrichs R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chemical Physics Letters. 1996;256:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schelvis JPM, Zhao Y, Marletta MA, Babcock GT. Resonance Raman characterization of the heme domain of soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16289–16297. doi: 10.1021/bi981547h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Marletta MA. Localization of the heme binding region in soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15959–15964. doi: 10.1021/bi971825x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nioche P, Berka V, Vipond J, Minton N, Tsai AL, Raman CS. Femtomolar sensitivity of a NO sensor from Clostridium botulinum. Science. 2004;306:1550–1553. doi: 10.1126/science.1103596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X, Sayed N, Beuve A, van den Akker F. NO and CO differentially activate soluble guanylyl cyclase via a heme pivot-bend mechanism. EMBO Journal. 2007;26:578–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erbil WK, Priceb MS, Wemmer DE, Marletta MA. A structural basis for H-NOX signaling in Shewanella oneidensis by trapping a histidine kinase inhibitory conformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19753–19760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911645106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim M, Xu C-L, Spiro TG. Differential sensing of protein influences by NO and CO vibrations in heme adducts. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:16834–16845. doi: 10.1021/ja064859d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decatur SM, Franzen S, DePillis GD, Dyer RB, Woodruff WH, Boxer SG. Trans effects in nitric oxide binding to myoglobin cavity mutant H93G. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4939–4944. doi: 10.1021/bi951661p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J-G, Zhang J, Franco R, Jia S-L, Moura I, Moura JJG, Kroneck PM, Shelnutt JA. The structural origin of nonplanar heme distortions in tetraheme ferricytochrome c3. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12431–12442. doi: 10.1021/bi981189i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Indiani C, de Sanctis G, Neri F, Santos H, Smulevich G, Coletta M. Effect of pH on axial ligand coordination of cytochrome c” from methylophilus methylotrophus and horse heart cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8234–8242. doi: 10.1021/bi000266i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu S, Smith KM, Spiro TG. Assignment of protoheme resonance Raman spectrum by heme labeling in myoglobin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118:12638–12646. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marzocchi MP, Smulevich G. Relationship between heme vinyl conformation and the protein matrix in peroxidases. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 2003;34:725–736. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olea J, Charles, Boon EM, Pellicena P, Kuriyan J, Marletta MA. Probing the function of heme distortion in the H-NOX family. ACS Chemical Biology. 2008;3:703–710. doi: 10.1021/cb800185h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coyle CM, Vogel KM, Rush I, Thomas S, Kozlowski PM, Williams R, Spiro TG, Dou Y, Ikeda-Saito M, Olson JS, Zgierski MZ. FeNO structure in distal pocket mutants of myoglobin based on resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4896–4903. doi: 10.1021/bi026395b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauhut G, Pulay P. Transferable scaling factors for density functional derived vibrational force fields. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99:3093–3100. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauhut G, Jarzecki AA, Pulay P. Density functional based vibrational study of conformational isomers: Molecular rearrangement of benzofuroxan. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1997;18:489–500. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merrick JP, Moran D, Radom L. An evaluation of harmonic vibrational frequency scale factors. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2007;111:11683–11700. doi: 10.1021/jp073974n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cundari TR, Raby PD. Theoretical estimation of vibrational frequencies involving transition metal compounds. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1997;101:5783–5788. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tran R, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Mathies RA. Resonance Raman spectra of an O2-binding H-NOX domain reveal heme relaxation upon mutation. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8568–8577. doi: 10.1021/bi900563g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boon EM, Huang SH, Marletta MA. A molecular basis for NO selectivity in soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature Chemical Biology. 2005;1:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nchembio704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makino R, Obayashi E, Homma N, Shiro Y, Hori H. YC-1 facilitates release of the proximal his residue in the NO and CO complexes of soluble guanylate cyclase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:11130–11137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Z, Pal B, Takenaka S, Tsuyama S, Kitagawa T. Resonance Raman evidence for the presence of two heme pocket conformations with varied activities in CO-bound bovine soluble guanylate cyclase and their conversion. Biochemistry. 2005;44:939–946. doi: 10.1021/bi0489208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pal B, Kitagawa T. Interactions of soluble guanylate cyclase with diatomics as probed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2005;99:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin E, Czarnecki K, Jayaraman V, Murad F, Kincaid JR. Resonance Raman and infrared spectroscopic studies of high-output forms of human soluble guanylyl cyclase. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:4625–4631. doi: 10.1021/ja0440912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibrahim M, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, Spiro TG. Probing soluble guanylate cyclase activation by CO and YC-1 using resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2010 doi: 10.1021/bi902214j. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pal B, Tanaka K, Takenaka S, Kitagawa T. Resonance Raman spectroscopic investigation of structural changes of CO-heme in soluble guanylate cyclase generated by effectors and substrate. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 2010 published online: Jan 26, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiro TG, Ibrahim M, Wasbotten IH. CO, NO and O2 as vibrational probes of heme protein active sites. In: Ghosh A, editor. The smallest biomolecules: Diatomics and their interactions with heme proteins. Elsevier; Amesterdam: 2008. pp. 96–123. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomita T, Ogura T, Tsuyama S, Imai Y, Kitagawa T. Effects of GTP on bound nitric oxide of soluble guanylate cyclase probed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10155–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi9710131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deinum G, Stone JR, Babcock JT, Marletta MA. Binding of Nitric Oxide and Carbon Monoxide to Soluble Guanylate Cyclase As Observed with Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1540–1547. doi: 10.1021/bi952440m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Denniger JW, Schelvis JPM, Brandish PE, Zhao Y, Babcock GT, Marletta MA. Interaction of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase with YC-1: Kinetic and Resonance Raman Studies. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4191–4198. doi: 10.1021/bi992332q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.