Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

The corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) family of peptides modulates intestinal inflammation and the CRH receptor 2 (CRHR2) suppresses postnatal angiogenesis in mice. We investigated the functions of CRHR1 and CRHR2 signaling during intestinal inflammation and angiogenesis.

METHODS

The activities of CRHR1 and CRHR2 were disrupted by genetic deletion in mice or with selective antagonists. A combination of in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro measures of angiogenesis were used to determine their activity. CRHR1−/− mice and CRHR2−/− mice with dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis were analyzed in comparison with wild-type littermates (controls).

RESULTS

Colitis was significantly reduced in mice in which CRHR1 activity was disrupted by genetic deletion or with an antagonist, determined by analyses of survival rate, weight loss, histological scores, and cytokine production. Inflammation was exacerbated in mice in which CRHR2 activity was inhibited by genetic deletion or with an antagonist, compared with controls. The inflamed intestines of CRHR1−/− mice had reduced microvascular density and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, whereas the intestines of CRHR2−/− mice had increased angiogenesis and VEGF-A levels. An antagonist of VEGFR2 activity alleviated colitis in CRHR2−/− mice. Ex vivo aortic vessel outgrowth was reduced when CRHR1 was deficient but increased when CRHR2 was deficient. The CRHR1 preferred agonist CRH stimulated tube formation, proliferation, and migration of cultured intestinal microvascular endothelial cells by phosphorylating Akt whereas the specific CRHR2 agonist Urocortin III had opposite effects.

CONCLUSION

CRHR1 promotes intestinal inflammation, as well as endogenous and inflammatory angiogenesis whereas CRHR2 inhibits these activities.

Keywords: neuropeptide, inflammatory bowel disease, PI3K, HIMECs

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the process of new blood vessel formation from a pre-existing one. It is an indispensable pathological component of chronic inflammatory diseases by promoting the recruitment of inflammatory cells, producing cytokines, matrix-degrading enzymes and chemokines, and supplying nutrients 1. Therefore, regulators that promote angiogenesis constitute new therapeutic targets for numerous vascular diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Abnormal or excessive angiogenesis is one of the major characteristics of IBD 1–3. Mucosal extracts from IBD patients induce migration and angiogenesis of human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMECs) 2. Moreover, clinical studies show that mucosal and plasma levels of several angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) and transforming growth factor-β, are increased in patients with active IBD 3. Additionally, an anti-angiogenic compound alleviates severity of the spontaneous colitis in interleukin (IL)-10 deficient mice 4. However, the detailed mechanism(s) by which angiogenesis participates in IBD pathophysiology remains to be elucidated.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is a 41-amino acid hypothalamic peptide that modulates the synthesis and release of adrenocorticotropic hormone from the pituitary, leading to the release of corticosteroid from the adrenal gland 5. Subsequent studies reveal the existence of other CRH-related peptides including urocortin (Ucn) I, Ucn II (stresscopin-related peptide), and Ucn III (stresscopin) 6–8. CRH and Ucn I-III exert their biological activities through binding to two G-protein coupled receptors, CRH receptors 1 and 2 9. CRH and Ucn I preferentially bind to CRHR1, whereas Ucn II and Ucn III exclusively bind to CRHR2 9. Upon binding to CRH receptors, CRH and Ucn I-III activate Gαs protein and the adenylyl cyclase/cAMP signaling pathway; additional pathways are also recruited in a cell specific manner 9. CRH and Ucn I-III are expressed in both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues including the intestine 8–11.

A major function of CRH is to coordinate the endocrine, behavioral, immune and visceral responses to stress. During acute stress, CRH alters gut propulsive motor function 11. Emerging evidence also links activation of the CRH-dependent signaling pathways with modulation of intestinal inflammation. For example, Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced enteritis was reduced in CRH or CRHR2 deficient mice 12, 13. In chronically stressed rats, central CRH reduced trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis 14. Furthermore, convergent studies indicate that CRHR2 is an angiogenic suppressor: 1) CRHR2 deficient mice become hypervascularized postnatally; 2) CRHR2 expression is diminished in tumor tissues along with increased microvessels; and 3) the expression of Ucn II inhibits vascularization and tumor growth 15–18. So far, however, no studies have suggested that either CRHR1 or CRHR2 signaling is involved in colitis-associated angiogenesis.

In the present study, we sought to investigate the differential effect of CRHR1 and CRHR2 activation on the manifestations of colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) and assess their role in colitis-associated angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

CRHR1 heterozygote mice (Crhr1tm1Klee) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. CRHR1 deficient mice and their wild type littermates (M&F, 8–12 weeks) were derived from heterozygous breedings. CRHR2 deficient mice were a gift from Dr. W. Vale (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) and had been backcrossed onto a B6 background (>N10). CRHR2 deficient mice and their wild type littermates (M&F, 8–12 weeks) were derived from heterozygous breedings. To induce colitis, mice were fed with DSS (4%, MP Biomedicals) dissolved in regular tap water for 14 days. Control mice were fed with regular tap water. Mice were weighed for body weight changes and monitored for rectal bleeding everyday. For histological evaluation, mice were fed with 4% DSS for 7 days and then euthanized. CD1 mice (eight-week-old male) were purchased from Charles River and injected i.p. with 200 μl astressin 2B solution (30 μg/kg in saline supplemented with 0.75% DMSO and 1% BSA, Sigma) or 200 μl antalarmin solution (20 mg/kg in saline supplemented with 0.75% DMSO and 1% BSA, Sigma) or vehicle. CRHR2 deficient mice and their wild type littermates were injected i.p. with 100 μl Ki8751 solution (10 mg/kg in saline supplemented with 1% DMSO, EMD-Calbiochem) or vehicle. All the inhibitors were injected daily. Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California at Los Angeles.

Cell cultures

HIMECs were isolated as previously described 19. HIMECs were cultured on the human fibronectin (3 μg/cm2, Sigma) coated plate with MCDB131 medium (Cellgro) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (BioWhittaker), 2.5% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B solution (BioWhittaker), heparin (90 μg/ml, Sigma), and endothelial cell growth factor (50 μg/ml, Roche Applied System). Cultures of HIMECs were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. HIMECs were used between passages 7 and 12.

Statistical analysis

Results are represented as the mean ± SD. Difference in survival was shown by Kaplan-Meier plot. The log-rank test was used to compare significant survival difference. Group data were compared by two-way ANOVA followed by the multiple-comparison Bonferroni t test or one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test to assess differences between groups. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare histological difference. Otherwise, paired and 2-tailed Student’s t tests were used to compare results from the experiments. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All other Materials and Methods are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Results

Genetic deficiency of CRHR1 ameliorates, but CRHR2 deficiency exacerbates intestinal inflammation

We first determined the differential function of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in intestinal inflammation. CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and their littermate control mice were subjected to DSS-induced colitis for 14 days and the inflammatory response was evaluated. Mortality and weight loss were reduced in CRHR1−/− mice compared with their littermate control CRHR1+/+ mice (Figure 1A and B). In contrast, mortality and weight loss were increased in CRHR2−/− mice compared with their littermate control CRHR2+/+ mice (Figure 1C and D). There was no difference on body weight gain in CRHR1−/− or CRHR2−/− mice compared with controls when supplemented with regular tap water instead of DSS (Supplementary Figure 1A and B). Taken together, these data indicate that two CRH receptors play an opposing role in DSS-induced colitis. Our results also indicate that CRHR1+/+ mice died earlier than CRHR2+/+ mice with colitis. This could probably be explained by strain differences between CRHR1 and CRHR2 mice (mixed and C57BL6J, respectively) that are also likely associated with different composition of their microflora, known to play an important role in the development of colitis 20.

Figure 1.

DSS-induced colitis is reduced in CRHR1−/− mice but increased in CRHR2−/− mice compared with littermate controls. Mice were fed with 4% DSS for 14 days. (A and C) Difference in the survival is shown by the Kaplan-Meier plot. The log-rank test indicates there are significant survival differences between CRHR1−/− and CRHR1+/+ mice (n=15 mice per genotype, P = 0.001) as well as between CRHR2−/− and CRHR2+/+ mice (n=15 mice per genotype, P < 0.0001). (B and D) Body weight data are mean ± SD (CRHR1: n=12–15 mice per genotype; CRHR2: n=6–11 mice per genotype). *P < 0.05 vs controls. Two-way ANOVA results show a significant genotype-treatment interaction; P < 0.0001 (B and D).

We further analyzed histological changes and inflammatory cytokine production. Representative photographs of the colon from CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and control mice treated with 4% DSS for 7 days indicated that CRHR1−/− mice were protected against inflammatory tissue damage compared with CRHR1+/+ mice (Figure 2A), whereas more severe tissue damage was observed in CRHR2−/− mice compared with CRHR2+/+ mice (Figure 2B). Histological scores from the quantifications of ulcers, leukocyte infiltration and submucosal edema were significantly decreased in CRHR1−/− mice, but increased in CRHR2−/− mice compared with controls (Figure 2C). Although the muscularis mucosae is intact in all mice groups, severe submucosal edema, distension of lamina propria with fibrous tissues, and infiltration with inflammatory cells were observed in CRHR1+/+ and CRHR2−/− mice (Figure 2A–C). Furthermore, the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6 and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) were decreased in CRHR1−/− mice but increased in CRHR2−/− mice compared with controls (Figure 2D–F). Basal expression levels of these cytokines in water-fed mice were similar between CRHR1−/− and CRHR1+/+ mice as well as between CRHR2−/− and CRHR2+/+ mice (Supplementary Figure 1C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that activation of CRHR1 increases pro-inflammatory responses in the intestine, while activation of CRHR2 triggers anti-inflammatory responses.

Figure 2.

Histological damage and inflammatory cytokine production induced by DSS are reduced in CRHR1−/− mice but increased in CRHR2−/− mice. (A and B) Representative images of H&E stained sections from the mice fed with 4% DSS for 7 days indicate reduced tissue damage in CRHR1−/− mice but increased tissue damage in CRHR2−/− mice compared with controls. Original magnification: 50X in the upper panel and 200X in the lower panel. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Ulcers, leukocyte infiltration and edema are decreased in CRHR1−/− mice but increased in CRHR2−/− mice with colitis compared with controls. Data are mean ± SD (n=8 mice per genotype). *P < 0.05 vs controls. (D–F) ELISA was performed to measure mouse KC (D), IL-6 (E) and TNFα (F) levels in tissues from DSS treated CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and control mice. Data are mean ± SD (n=3–7 mice per genotype). *P < 0.05 vs controls.

The CRHR1 antagonist reduces intestinal inflammation, whereas the CRHR2 antagonist increases it

We next tested whether pharmacological blockade of CRHR1 or CRHR2 reproduces the differential effects of the genetic deficiency. DSS-induced mortality was decreased in mice injected i.p. daily with a specific CRHR1 antagonist antalarmin (20 mg/kg) but increased in mice with a selective CRHR2 antagonist astressin 2B (30 μg/kg), compared with the vehicle-treated group (Figure 3A). Likewise, antalarmin treatment blunted DSS-induced weight loss, whereas astressin 2B treatment accelerated weight loss (Figure 3B). Histological analysis of the colon showed that the antalarmin group had lower histological scores, but the astressin 2B group showed higher histological scores compared with the vehicle group (Figure 3C). Colonic levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and KC were decreased in the antalarmin group but increased in the astressin 2B group compared with the vehicle group (Figure 3D–F). These results are in line with the results obtained from CRHR1−/− and CRHR2−/− mice, confirming an opposite role of these CRH receptors in the development of colitis.

Figure 3.

The CRHR1 or CRHR2 antagonist attenuates or worsens DSS-induced colitis, respectively. (A and B) DSS-induced mortality and body weight loss are reduced in mice (CD1) with a CRHR1 specific antagonist, antalarmin (Antal, 20 mg/kg) but increased in mice with a CRHR2 specific antagonist, astressin 2B (Ast2B, 30 μg/kg) compared with the vehicle control. (A) Difference in the survival is shown by Kaplan-Meier plot. The log-rank test followed by the multiple-comparison Bonferroni method shows that there are significant survival differences between water vs DSS, water vs DSS plus Ast2B, DSS vs DSS plus Antal, and DSS vs DSS plus Ast2B treated mice (n=4–10 mice per genotype, P < 0.05). (B) Body weight data are mean ± SD (n=4–10 mice per genotype). (C) Ulcers, leukocyte infiltration and edema are reduced by Antal but increased by Ast2B in mice with colitis. Data are mean ± SD (n=4–8 mice per genotype). (D–F) ELISA was performed to measure mouse KC (D), IL-6 (E) and TNFα (F) levels in the colon from DSS treated mice with Antal or Ast2B or vehicle for 7 days. Data are mean ± SD (n=4–7 mice per genotype). The results of one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test show a significant difference compared to DSS alone treated mice; *P < 0.05 (B–D).

Inhibition of angiogenesis using a VEGFR2 activity inhibitor alleviates colitis in CRHR2−/− mice

The results above prompted us to define the mechanisms by which activations of CRHR1 and CRHR2 differentially regulate intestinal inflammation. Recent studies indicate that CRHR2 signaling pathways trigger anti-angiogenic responses 15. Therefore, we hypothesized that the opposite effects of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in colitis might be due to a differential regulation of angiogenesis. To test this, we first measured the expression level of the pro-angiogenic factor VEGF-A in the colons of CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/− and control mice. Mice were supplemented with 4% DSS for 7 days and then the entire colon was excised. Indeed, the amount of VEGF-A protein in the colon was lower in CRHR1−/− mice, but higher in CRHR2−/− mice compared with controls, suggesting reduced or increased angiogenic responses, respectively (Figure 4A and B). The basal expression level of VEGF-A in CRHR1−/− or CRHR2−/− mice was not different from that in controls (Supplementary Figure 2A). We further investigated the effect of CRHR1 or CRHR2 deficiency on colitis associated angiogenesis by examining the expression level of CD31, an established marker of angiogenesis. Microvascular density was decreased in CRHR1−/− mice with colitis whereas increased in CRHR2−/− mice with colitis compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 2B). These data suggest that CRHR1 and CRHR2 regulate colitis-associated angiogenesis in an opposite way.

Figure 4.

Increased vs decreased VEGF-A levels during colitis in CRHR2−/− vs CRHR1−/− mice. VEGFR2 blockade reduces colitis in CRHR2−/− mice. (A and B) ELISA was performed to measure VEGF-A levels in the colon from DSS treated (for 7 days) CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and control mice. Data are mean ± SD (n=6–7 mice per genotype). *P < 0.05 vs controls. (C and D) DSS-induced colitis is reduced in CRHR2−/− mice injected i.p. with Ki8751 (Ki, 10 mg/kg) compared with the vehicle control. Mice were fed with 4% DSS for 14 days. (C) Difference in the survival is shown by Kaplan-Meier plot. The log-rank test indicates there are significant survival differences between CRHR2−/− mice with Ki and CRHR2−/− mice (n=19 mice per genotype, P < 0.001). (D) Body weight data are mean ± SD (n=15 mice per genotype). *P < 0.05 vs CRHR2−/− mice. (E with quantification in F) Immunohistochemistry on CD31 demonstrates that microvascular density is reduced in CRHR2−/− mice with Ki. H&E staining also shows reduced tissue damage in the Ki-treated mice compared with vehicle treated mice. Scale bar: 50 μm.

The above results showed that CRHR2−/− mice were more susceptible to colitis (Figure 1C and D) and displayed increased colitis-associated angiogenesis than controls (Supplementary Figure 2B). We therefore tested whether blocking angiogenesis could alleviate colitis symptoms enhanced by CRHR2 deficiency. A cell permeable VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor, Ki8751 (10 mg/kg) was injected daily to CRHR2−/− mice, while they were supplied with 4% DSS. Pharmacological inhibition of the VEGFR2 activity alleviated colitis symptoms of CRHR2−/− mice compared with the vehicle group (Figure 4C and D). Microvascular density shown by CD31 staining was also reduced by Ki8751 compared with the vehicle group (Figure 4E, F and Supplementary Figure 2E). Several previous reports demonstrated that blocking angiogenesis could relieve colitis in mice 4, 21, 22. In agreement with those reports, Ki8751 modestly improved survival and body weight loss in wild type mice with colitis (Supplementary Figure 2C and D). The extent of protection against colitis, however, was less in wild type mice than CRHR2−/− mice. These results suggest that CRHR2 reduces inflammation by functioning as an angiogenic inhibitor; therefore, blocking angiogenesis can reduce the severity of colitis associated with CRHR2 deficiency.

Deletion of CRHR1 impairs the vessel outgrowth from aortic explants, whereas deletion of CRHR2 enhances it

To dissect the role of CRHR1 and CRHR2 on vessel growth, aortic ring assays were performed. Aortic explants were excised from CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and control mice, embedded in the Matrigel and cultured for up to 14 days in the presence of mouse VEGF (25 ng/ml). Quantitative analyses were performed to measure average vessel length. Our results showed that aortic vessel outgrowth was significantly reduced in CRHR1−/− mice compared with CRHR1+/+ mice, whereas the outgrowth was enhanced in CRHR2−/− mice compared with CRHR2+/+ mice (Figure 5A and B). Addition of CRH or Ucn III exogenously did not further enhance or inhibit these responses (data not shown), suggesting that endogenously expressed CRH or Ucn by vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) may play a role. In addition, the growth rate of vessels was slightly delayed in the explants of CRHR2+/+ mice compared with CRHR1+/+ mice, and this was probably because CRHR1 and CRHR2 mice were from different background strains (mixed and C57BL6J, respectively). Taken together, these data indicate that CRHR1 is pro-angiogenic, whereas CRHR2 is anti-angiogenic.

Figure 5.

Deletion of CRHR1 impairs the vessel outgrowth from aortic explants, whereas deletion of CRHR2 enhances it. (A) Aortic explants from CRHR1−/−, CRHR2−/−, and control mice were embedded in Matrigel and cultured for up to 14 days with mouse VEGF (25 ng/ml). Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Average vessel length on samples pooled from 3 independent experiments is shown as mean ± SD (n=3 mice per genotype). *P < 0.005 vs wild type littermates.

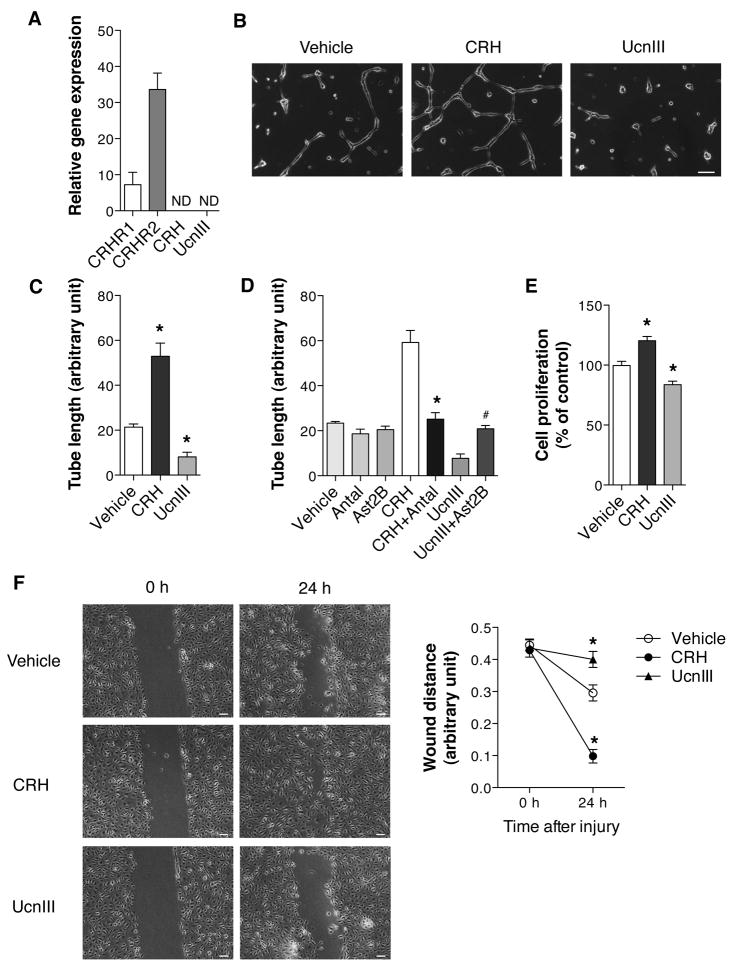

Stimulation of CRHR1 promotes angiogenesis whereas activation of CRHR2 inhibits it in HIMECs

The above results suggest that the opposite effects of CRHR1 and CRHR2 may be due to their differential regulations on angiogenesis. Hence, the next logical step would be to examine the role of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in intestinal angiogenesis. First, we tested whether HIMECs express any of the CRH family peptides and/or CRHRs using quantitative real time PCR and found that these cells express CRHR1 and CRHR2, but not CRH or Ucn III (Figure 6A). Next, we examined participation of CRH receptors in angiogenesis using in vitro models of endothelial cell tube formation, proliferation and migration. When plated between two layers of Matrigel, HIMECs develop tubes over the course of 5–6 h as shown by time-lapse images (Supplementary Figure 3). We found that activation of CRHR1 by CRH (10 nM) enhanced tube formation by 2.8-fold compared with the vehicle control (Figure 6B and C). In contrast, Ucn III (10 nM), the specific ligand of CRHR2, inhibited tube formation by 2-fold compared with the vehicle control (Figure 6B and C). To confirm whether the CRH- or Ucn III-induced tube response is mediated through their preferential receptor CRHR1 or CRHR2, we used selective CRHR1 or CRHR2 antagonists, antalarmin or astressin2B, respectively. Antalarmin (100 nM) inhibited CRH-induced tube formation (Figure 6D), and astressin 2B (1 nM) prevented Ucn III-induced reduction of tube formation (Figure 6D). Moreover, the results obtained from the XTT assays indicated that CRH increased cell proliferation, but Ucn III decreased it (Figure 6E). Furthermore, wound healing assays showed that CRH promoted cell migration and reduced the overall denuded area, whereas Ucn III-treated cells showed less migration as indicated by more denuded areas compared with the vehicle control (Figure 6F and G). Taken together, these results suggest that activation of CRHR1 promotes angiogenesis of intestinal ECs, whereas activation of CRHR2 inhibits this response.

Figure 6.

CRH augments tube formation, but Ucn III inhibits it. (A) Quantitative real time PCR analyses reveal that HIMECs express both CRHR1 and CRHR2 but not CRH or Ucn III. The cDNA from human NCM460 colonocytes was used as a calibrator. ND: not detected (B with quantification in C) CRH increases spontaneous tube formation but Ucn III decreases it. The HIMECs were subjected to a tube formation assay and then medium containing CRH (10 nM) or Ucn III (10 nM) or vehicle was added for 5 h. Representative photos from 5 independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. *P < 0.05 vs vehicle. (D) CRH or Ucn III-induced tube responses are diminished in the presence of antalarmin (1 nM) or astressin 2B (100 nM). The antagonists were added for 30 min prior to the addition of CRH or Ucn III or vehicle. *P < 0.05 vs CRH. #P < 0.05 vs Ucn III. (E) The result of XTT assays indicate that CRH increases cell proliferation but Ucn III decreases it. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs vehicle. (F) The results of wound injury assays (24 h) indicate that CRH enhances wound closure but Ucn III delays it. Representative photos of 3 independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. *P < 0.05 vs vehicle. Data are mean ± SD. The results of one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test show a significant difference compared to vehicle (C, E, F).

Activation of CRHR1 increases Akt phosphorylation whereas that of CRHR2 reduces it

We next defined the mechanisms by which CRHR1 and CRHR2 oppositely regulated angiogenesis. A previous report indicated that activation of CRHR2 resulted in reduced VEGF release from SMCs 15. To this end, we first examined whether CRHRs regulated the production of various pro-angiogenic factors in HIMECs. VEGF-A was not detected in ECs stimulated with CRH or Ucn III (data not shown). Moreover, neither CRH nor Ucn III affected FGF and IL-8 productions (Supplementary Figure 4A and B). These data indicate that regulation of angiogenesis by CRH or Ucn III was not mediated through altering the production of pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF, FGF and IL-8. Therefore, we further investigated whether the CRH family of peptides regulated angiogenic signaling pathways. We previously reported an interplay of PI3K and PLCγ at the level of their common substrate phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate (PtdIns-4,5P2) to regulate vessel stability 23. Especially, PI3K contributes to signaling downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases and integrins, both of which are essential for growth factor-driven vessel formation and angiogenesis 24. Given that CRHRs regulated tube response and G protein coupled receptors activated the PI3K pathway, we considered the possibility that CRHRs might regulate PI3K activity to control angiogenesis. In CRH-stimulated HIMECs, phospho-Akt as an output of PI3K activity was increased concentration-dependently (Figure 7A and B). However, when the cells were stimulated with Ucn III, phospho-Akt was decreased (Figure 7A and B). Since it seemed that CRH increased tube responses by phosphorylating Akt, we next tested whether a PI3K inhibitor could reduce CRH-dependent tube formation. Indeed, in the presence of a PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM), CRH-enhanced tube responses were suppressed (Figure 7C). The enzyme PI3K utilizes PtdIns-4,5P2 to generate PtdIns-3,4,5P3 which triggers the downstream signaling pathway including Akt phosphorylation 25. Moreover, we previously showed that increasing the cellular level of PtdIns-4,5P2 by adding the mixture of synthetic PtdIns-4,5P2 (PI45P) and histone was able to increase Akt phosphorylation 23. Therefore, we tested if increasing the cellular level of PtdIns-4,5P2 prevented Ucn III-inhibited tube responses. Indeed, the addition of PtdIns-4,5P2 prevented the inhibition of tube responses by Ucn III, while the addition of non-substrate PtdIns-3P1 (PI3P) did not show any effect (Figure 7D). Taken together, these results suggest that CRH activates the PI3K pathway which will help maintain vessel stability. Ucn III, however, decreased PI3K activity, and this will prevent vessels from growing and/or being stabilized.

Figure 7.

CRH stimulates the PI3K pathway, whereas Ucn III inhibits it in HIMECs. (A with quantification in B) Western blot analysis shows concentration-dependent increase in phospho-Akt by CRH (10 nM, 15 min) but decrease by Ucn III (10 nM, 15 min) (C) Inhibition of PI3K activity by LY294002 (LY) diminishes tube formation by CRH. The HIMECs were subjected to a Matrigel tube formation assay and then medium containing LY294002 (5 μM) was added for 30 min prior to the addition of CRH (10 nM) or vehicle for 5 h. *P < 0.05 vs CRH. (D) Synthetic lipid substrate of PI3K rescued the inhibition of tube response by Ucn III. HIMECs were subjected to a tube assay. A mixture of synthetic lipids (PI45P or PI3P) and histone was added simultaneously with Ucn III (10 nM). *P < 0.05 vs Ucn III plus PI3P. Data are mean ± SD. The results of one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test show a significant difference (B, C).

Discussion

The CRH family of peptides differentially regulates intestinal angiogenesis

Here we identify what we believe to be a novel function for the CRH family of peptides as a regulator of angiogenesis in the inflamed intestine. Our first indication that endogenous CRH might be pro-angiogenic came from studies in mice with global deletion of CRHR1 that showed severely delayed vessel outgrowth from aortic explants. CRH is densely expressed on SMCs in the vascular system15 and CRH-producing tumor cells significantly enhance angiogenesis when injected subcutaneously into nude mice 26 suggesting endogenous regulation of angiogenesis by the CRH system. Notably, the expression of the pro-angiogenic VEGF-A level is reduced in the colon from CRHR1−/− mice with colitis, indicating that impaired angiogenesis in CRHR1−/− mice might contribute to reduced colitis. Since the intestinal ECs do not produce VEGF-A in response to CRH, VEGF-A produced from SMCs might contribute to its increased level in the inflamed colon. Furthermore, we observed that activation of CRHR1 increases tube formation, cell viability and migration of cultured HIMECs. These results suggest that activation CRHR1 can stimulate intestinal angiogenesis.

Our results showing that CRHR2 deficiency is associated with enhanced vessel outgrowth from aortic explants indicate that endogenous Ucn III and/or other CRHR2 ligands might be anti-angiogenic. In contrast to CRHR1−/− mice, expression of VEGF-A is increased in CRHR2−/− mice with colitis. These results are consistent with a previous report indicating that activation of CRHR2 reduces VEGF-A release in SMCs and inhibits capillary formation of rat aortic ECs 15. Inhibition of VEGFR2 kinase activity ameliorates several parameters of colitis in CRHR2−/− mice to the extent seen in wild type mice, suggesting that exacerbated colitis in CRHR2−/− mice is due to increased angiogenesis. The notion that decreased tube formation, cell viability and migration in cultured ECs by Ucn III is further supported by a recent study suggesting a novel role for CRHR2 as a suppressor of vascularization 15. Another study also showed that viral expression of Ucn II in Lewis Lung Carcinoma Cell tumors inhibited tumor growth by suppressing vascularization 16. Moreover, in prostate and renal cell carcinoma, loss of CRHR2 expression is associated with tumor angiogenesis 17, 18. These findings indicate that activation of CRHR2 triggers anti-angiogenic responses.

The exact mechanism by which the CRH family of peptides regulates intestinal angiogenesis needs further investigation. The PI3K pathway including the serine/threonine kinase Akt/PKB is known to mediate endothelial cell growth, survival and migration 23. The results that CRH increased the level of phospho-Akt and that the inhibitor of PI3K activity diminished CRH-induced tube response suggest that the PI3K signaling is a main contributor to CRH-mediated angiogenesis. Moreover, since exogenously added PtdIns-4,5P2 rescued tube inhibition by Ucn III, PtdIns-4,5P2-dependent signaling pathways might be involved in the CRH-driven angiogenic process. These pathways include diacylglycerol-dependent protein kinase C activation, inositol triphosphate-induced intracellular calcium increase and inhibition of tyrosine kinases (c-abl) 27, 28.

The CRH family of peptides differentially regulates intestinal inflammation

Emerging evidence from our group and others also links activation of CRH receptors with intestinal inflammation. Inhibition of CRH by dsRNA or use of genetically deficient mice results in dramatically reduced ileal inflammation in C. difficile toxin A-induced enteritis 12, 29. Blocking CRHR1 by antalarmin also inhibits toxin A-induced intestinal secretion and inflammation 30. Ucn I-expressing cells are significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of advanced UC 31. Conversely, CRH deficiency is also associated with reduced acute colitis, two days after intracolonic TNBS administration 32. These studies indicate that activation of CRHR1 by CRH or Ucn I enhances intestinal inflammation.

On the other hand, upon CRHR2 activation, inflammatory responses are increased or decreased depending on the experimental models used. In toxin A-induced enteritis, Ucn II and CRHR2 exert pro-inflammatory responses 13. However, in TNBS-induced colitis, CRHR2 expression levels are decreased 33. Additionally, two other G-protein coupled neuropeptide receptors neurokinin-1 and neurotensin 1, exert anti-inflammatory or protective effects in chronic experimental colitis 34, 35.

The CRH family of peptides functions as a liaison between angiogenesis and inflammation

Several cellular players participating in the inflammatory responses are also involved in angiogenesis. IL-8 increases angiogenesis of HIMECs through its CXCR2 receptor and enhances endothelial permeability by VEGFR2 transactivation 36, 37. The angiogenic regulator angiopoietin-2 also mediates inflammatory responses in DSS-induced colitis 38. In addition, natriuretic peptides and their downstream effecter guanylyl cyclase-A regulate ischemia-induced angiogenesis in mice 39. Increased levels of VEGF-A and VEGFR2 are also evident in samples from patients with IBD and mice with colitis 40. Results from the present study suggest that the CRH system modulates intestinal inflammation and yet regulates either endogenous or inflammatory angiogenesis. Future work is needed to assess the precise mechanism of actions of the CRH family of peptides on the intestinal vascular system.

In conclusion, results of the present study demonstrate that the CRH family of peptides is critically involved in colitis-associated angiogenesis and endothelial CRH receptors are essential players for intestinal angiogenesis. These results may form the basis for novel therapeutic approaches to treat devastating intestinal inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a Young Clinical Scientist Award from “FAMRI, Inc.” (EI and SHR) and by NIH/NIDDK 1KO1 DK083336 (EI), 1KO1 DK079015 (SHR), RO1 DK50894 and RO1 DK69854 (CF), VA Career Scientist Award and DK41301 (YT), and PO1 DK33506 and RO1 DK072471 (CP).

Abbreviations

- Antal

antalarmin

- Ast2B

astressin 2B

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRH

Corticotropin releasing hormone

- CRHR

CRH receptor

- DSS

dextran sodium sulfate

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- HIMECs

human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- SMCs

Smooth muscle cells

- TNBS

trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid

- Ucn

Urocortin

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Authors disclose no conflicts.

Author contribution:

1. Eunok Im: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtained funding; technical, or material support; study supervision

2. Sang Hoon Rhee: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding

3. Yong Seek Park: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

4. Claudio Fiocchi: interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding

5. Yvette Taché: analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding

6. Charalabos Pothoulakis: study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; technical, or material support; study supervision

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jackson JR, Seed MP, Kircher CH, et al. The codependence of angiogenesis and chronic inflammation. FASEB J. 1997;11:457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danese S, Sans M, de la Motte C, et al. Angiogenesis as a novel component of inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2060–2073. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanazawa S, Tsunoda T, Onuma E, et al. VEGF, basic-FGF, and TGF-beta in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:822–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danese S, Sans M, Spencer DM, et al. Angiogenesis blockade as a new therapeutic approach to experimental colitis. Gut. 2007;56:855–862. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.114314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, et al. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, et al. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7570–7575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121165198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, et al. Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2843–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med. 2001;7:605–611. doi: 10.1038/87936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:260–286. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muramatsu Y, Fukushima K, Iino K, et al. Urocortin and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor expression in the human colonic mucosa. Peptides. 2000;21:1799–1809. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taché Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:33–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anton PM, Gay J, Mykoniatis A, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) requirement in Clostridium difficile toxin A-mediated intestinal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8503–8508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402693101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokkotou E, Torres D, Moss AC, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 2-deficient mice have reduced intestinal inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:3355–3361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Million M, Tache Y, Anton P. Susceptibility of Lewis and Fischer rats to stress-induced worsening of TNB-colitis: protective role of brain CRF. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1027–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bale TL, Giordano FJ, Hickey RP, et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 is a tonic suppressor of vascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7734–7739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102187099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao Z, Huang Y, Cleman J, et al. Urocortin2 inhibits tumor growth via effects on vascularization and cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3939–3944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712366105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tezval H, Jurk S, Atschekzei F, et al. Urocortin and corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 in human renal cell carcinoma: disruption of an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and proliferation. World J Urol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tezval H, Jurk S, Atschekzei F, et al. The involvement of altered corticotropin releasing factor receptor 2 expression in prostate cancer due to alteration of anti-angiogenic signaling pathways. Prostate. 2009;69:443–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binion DG, West GA, Ina K, et al. Enhanced leukocyte binding by intestinal microvascular endothelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1895–907. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1620–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandor Z, Deng XM, Khomenko T, et al. Altered angiogenic balance in ulcerative colitis: a key to impaired healing? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolstanova G, Khomenko T, Deng X, et al. Neutralizing anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody reduces severity of experimental ulcerative colitis in rats: direct evidence for the pathogenic role of VEGF. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:749–57. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im E, Kazlauskas A. Regulating angiogenesis at the level of PtdIns-4,5-P2. EMBO J. 2006;25:2075–2082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto T, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signal transduction. Sci STKE 2001. 2001:RE21. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.112.re21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arbiser JL, Karalis K, Viswanathan A, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates angiogenesis and epithelial tumor growth in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:838–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irvine R. Nuclear lipid signaling. Sci STKE 2000. 2000:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.48.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plattner R, Irvin BJ, Guo S, et al. A new link between the c-Abl tyrosine kinase and phosphoinositide signalling through PLC-gamma1. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:309–319. doi: 10.1038/ncb949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.la Fleur SE, Wick EC, Idumalla PS, et al. Role of peripheral corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin II in intestinal inflammation and motility in terminal ileum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7647–7652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408531102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wlk M, Wang CC, Venihaki M, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone antagonists possess anti-inflammatory effects in the mouse ileum. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:505–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saruta M, Takahashi K, Suzuki T, et al. Urocortin 1 in colonic mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5352–5361. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gay J, Kokkotou E, O’Brien M, et al. CRH-deficiency is associated with reduced local inflammation in a mouse model of experimental colitis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3403–3409. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang J, Hoy JJ, Idumalla PS, et al. Urocortin 2 expression in the rat gastrointestinal tract under basal conditions and in chemical colitis. Peptides. 2007;28:1453–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brun P, Mastrotto C, Beggiao E, et al. Neuropeptide neurotensin stimulates intestinal wound healing following chronic intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G621–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castagliuolo I, Morteau O, Keates AC, et al. Protective effects of neurokinin-1 receptor during colitis in mice: role of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:271–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Dwinell MB, et al. Angiogenic effects of interleukin 8 (CXCL8) in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells are mediated by CXCR2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8508–8515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petreaca ML, Yao M, Liu Y, et al. Transactivation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 by interleukin-8 (IL-8/CXCL8) is required for IL-8/CXCL8-induced endothelial permeability. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:5014–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ganta VC, Cromer W, Mills GL, et al. Angiopoietin-2 in experimental colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ibd.21150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhn M, Volker K, Schwarz K, et al. The natriuretic peptide/guanylyl cyclase--a system functions as a stress-responsive regulator of angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2019–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI37430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Sans M, et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:585–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.