Abstract

The small heat shock protein αB-crystallin is a molecular chaperone that is induced by stress and protects cells by inhibiting protein aggregation and apoptosis. To identify novel transcriptional regulators of the αB-crystallin gene, we examined the αB-crystallin promoter for conserved transcription factor DNA binding elements and identified a putative response element (RE) for the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Ectopic expression of wild-type p53 induced αB-crystallin mRNA and protein with delayed kinetics compared to p21. Additionally, the induction of αB-crystallin by genotoxic stress was inhibited by siRNAs targeting p53. Although the p53-dependent transactivation of an αB-crystallin promoter luciferase reporter required the putative p53RE, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) failed to detect p53 binding to the αB-crystallin promoter. These results suggested an indirect mechanism of transactivation involving p53 family members p63 or p73. ΔNp73 was dramatically induced by p53 in a TAp73-dependent manner, and silencing p73 suppressed the transcriptional activation of αB-crystallin by p53. Moreover, ectopic expression of ΔNp73α (but not other p73 isoforms) increased αB-crystallin mRNA levels in the absence of p53. Collectively, our results link the molecular chaperone αB-crystallin to the cellular genotoxic stress response via a novel mechanism of transcriptional regulation by p53 and p73.

Keywords: p53, p73, ΔNp73α, TAp73, αB-crystallin, DNA damage

Introduction

αB-crystallin/HspB5 is a widely expressed member of the small heat shock protein (sHSP) family, which also includes Hsp27/HspB1 and HspB2/MKBP, defined by the presence of a conserved α-crystallin domain [1]. αB-crystallin promotes cell survival following its induction by cellular stressors, such as heat and reactive oxygen species (ROS), by inhibiting the aggregation of denatured or misfolded proteins and by increasing intracellular glutathione levels [2-5]. More recently, αB-crystallin has been shown to inhibit apoptosis by suppressing caspase-3 activation and by sequestering pro-apoptotic effectors, such as Bax and Bcl-Xs, in the cytoplasm, thereby conferring additional cytoprotection against cellular stress [6-9]. HSF-1, lens epithelial derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75 and the glucocorticoid receptor have been demonstrated to regulate the induction of αB-crystallin in response to hyperthermia, ROS and glucocorticoids [10-12].

We postulated that additional transcriptional regulators of the mammalian stress response might regulate αB-crystallin gene expression. Here, we report that the αB-crystallin gene is regulated by a novel mechanism involving multiple p53 family members. The p53 protein is a critical mediator of the cellular response to genotoxic stress and plays a fundamental role in tumor suppression, as evidenced by the frequent inactivation of the p53 pathway in a broad spectrum of tumors [13]. Classically, p53 inhibits tumor initiation by transcriptionally coordinating several cellular programs that prevent propagation of damaged genomes: cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence and apoptosis. p53 biology has been dramatically revised with the discovery of additional p53 family members, p63 and p73. TAp63 and TAp73 have been shown to transactivate many p53 target genes [14-16]. Moreover, p63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis and/or cell cycle arrest in some systems, and p73 can mediate these responses in the absence of p53 [17-19]. Through an alternative promoter, the p63 and p73 genes also express ΔN isoforms which lack the N-terminal transactivation domain. ΔNp63 and ΔNp73 act in a dominant negative fashion on p53 activity by competing for p53RE binding, and on TAp63 and TAp73 activity through the formation of inactive heterotetramers [20, 21]. In light of their ability to inhibit p53, ΔN isoforms likely play an important role in tumor biology. Indeed, ΔNp73 expression enhances Ras-mediated transformation, counters p53-mediated apoptosis in development, and is expressed in several clinically aggressive tumor types [22-27]. In addition to this antagonistic function, ΔNp63 and ΔNp73 appear to independently transactivate genes and induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [28-31]. Alternative 3′ splicing generates 3 p63 (α, β, γ) and 8 p73 (α, β, γ, ζ, δ, θ, η, η1) C-terminal isoforms [32, 33]. Additionally, p53 family members transcriptionally regulate each other to form overlapping positive and negative feedback loops [20, 34, 35]. The complexity of the p53 family transcriptional regulation network and its role in cancer are topics of intense investigation and have yet to be fully resolved.

In this manuscript, we demonstrate that genotoxic stress induces αB-crystallin by a p53-dependent mechanism. Intriguingly, p53 activates αB-crystallin gene expression by an indirect mechanism that results in delayed induction of αB-crystallin compared to p21. Instead, p53 robustly induces ΔNp73, which in turn activates αB-crystallin gene expression. Taken together, our findings point to a novel link between αB-crystallin and genotoxic stress that is regulated by the cooperative actions of multiple p53 family members.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

EJ-p53 cells (kind gift of Sam W. Lee, Harvard Medical School) were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone), 300 μg/mL G418 (Mediatech), 100 μg/mL hygromycin B (Mediatech), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine (Invitrogen). Tetracycline (1 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) was added fresh to the media every 3-4 days to maintain repression of p53 [36]. MCF-10A cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM/F-12 (1:1 mixture, Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Invitrogen), 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 ng/mL cholera toxin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 ng/mL EGF (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine. Phoenix cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine. Doxorubicin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO.

Retrovirus production and infection

Retrovirus was produced in Phoenix cells and used to infect MCF-10A as previously described [37, 38]. Briefly, 2.5 × 106 Phoenix cells were transfected with 5.45 μg pLXSN retroviral expression plasmid and 0.55 μg pMD2-VSV-G (a kind gift of Ronald DePinho, Harvard Medical School) using 50 μL 2.5 M CaCl2 and 500 μL 2X HBS, pH 7.10 with 25 μM chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich) in the media. Retrovirus production was carried out at 32°C, and EGF was added to 20 ng/mL in addition to polybrene after 0.45 μm-filtering. Retroviral supernatant was used to infect 300,000 MCF-10A cells in 6 cm dishes for 3-5 h, then fresh media was added.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Point mutations were made using the QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) per the manufacturer’s protocol with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. The coding sequence of wild-type p53 (GenBank NM_000546) in the pLXSN retroviral expression vector was mutated to R175H and R273H. The αB-crystallin/HspB2 promoter sequence in the pGL3 luciferase reporter vector was mutated at the 5′ and 3′ p53RE half-sites (the sequences of the putative wild-type and mutated p53 REs are shown in Fig. 2A). Mutations were confirmed by direct sequencing.

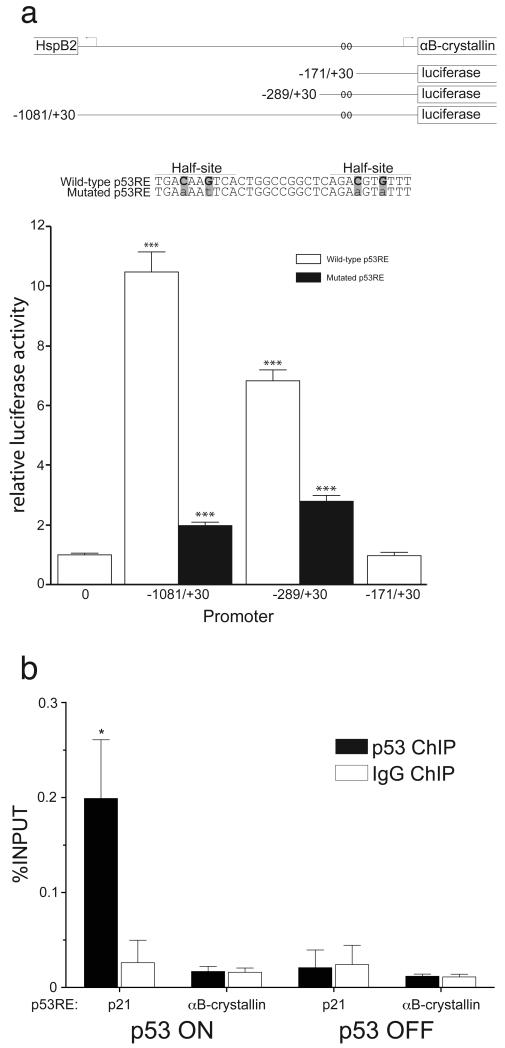

Fig. 2. The putative p53RE mediates p53-dependent activation of the αB-crystallin promoter without binding p53.

(a) The top line schematically depicts the shared αB-crystallin/HspB2 promoter. The transcriptional start sites of αB-crystallin and HspB2 are indicated by bent arrows; open-ended boxes depict coding sequences. Below, the portion of the promoter upstream of the firefly luciferase coding sequence in each of the pGL3 reporter constructs is displayed. The indicated point mutations in the putative p53RE in the αB-crystallin promoter (highlighted in gray) were introduced to abrogate wild-type p53 protein binding. EJ-p53 cells transfected with 100ng of wild-type, truncated, or p53RE-mutated αB-crystallin promoter luciferase reporter and 100 pg of a Renilla luciferase reporter were induced to express p53 for 24 h. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and is indicated relative to promoter-less pGL3-Basic sample activity. For wild-type p53RE samples, statistical significance (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test) is noted for the difference compared to the promoter-less pGL3-Basic construct (labeled ‘0’). For the mutated p53RE samples, statistical significance is noted for differences compared to wild-type p53RE. ***P < 0.001. (b) EJ-p53 cells after 24 h with or without p53 induction were assayed by p53 ChIP for binding of p53 to the αB-crystallin promoter. ChIP-isolated DNA was assayed by real-time RT-PCR with primers flanking the putative p53REs in the αB-crystallin or p21 promoters. The fraction of input chromatin (%INPUT) immunoprecipitated was calculated by the standard curve method. Statistical significance (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test) is noted for %INPUT differences between p53 and IgG ChIP under each condition. *P < 0.05.

Luciferase experiments

EJ-p53 cells (80,000 cells per well in a 24-well plate) were transfected with 300 ng pcDNA3 empty vector, 100 ng pGL3 firefly luciferase reporter construct, and 100 pg pRL-CMV Renilla luciferase expression vector (Promega) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay kit reagents (Promega) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were lysed with 1X Promega Passive Lysis Buffer and transferred to a Lumitrac 200 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured for 30 s following LAR II and Stop-n-Glo injection, respectively, in a Clarity Luminescence Microplate Reader (BioTek). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla activity.

Protein isolation and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0), supplemented with 1% each: Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X, Sigma-Aldrich), Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Set II (Calbiochem), and 100 mM PMSF (Sigma). Lysate protein concentration was measured by BCA colorimetry (BCA Protein Assay Kit, Pierce). DTT was added to 100 mM, 5X sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% w/v SDS, 50% (v/v) glycerol, ~0.4% w/v bromophenol blue) added, and lysates were boiled.

Proteins lysates were separated by size using SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore) using a semi-dry transfer apparatus. The membranes were blocked for 1 h at RT in TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat milk, incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 2, and then incubated with anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Southern Biotech) for 1 h at RT. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) assay.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR

RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was made from 0.5 μg total RNA with the ReactionReady First Strand Synthesis Kit (SABiosciences) per manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was used as template for real-time PCR with 0.4 μM each primer using the RT2 SYBR Green/ROX PCR Master Mix (SABiosciences). Commercially available primer sets listed in Supplementary Table 3 (RT2 qPCR Primer Set for Human genes, SABiosciences) were used to amplify the following genes: CDKN1A (p21), CRYAB (αB-crystallin), GAPDH, HSPB1 (Hsp27), HSPB2 and TP53. Primer sequences obtained from the literature (Supplementary Table 4) were used to amplify TAp63, ΔNp63, TAp73, and ΔNp73 [39].

Reactions were carried out in triplicate in 384-Well Clear Optical Reaction Plates (Applied Biosystems) using a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR Machine (Applied Biosystems) with the following thermal cycling profile: 50°C 2 min, 95°C 10 min, 40× (95°C 15 sec, 60°C 1 min with fluorescence detection). SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems) generated cycle threshold (Ct) values, which were converted to L values by the standard curve method, followed by internal normalization to the GAPDH L value. Each fold-induction value reported is the mean of 3-6 independent experiments.

siRNA oligo duplex transfection

MCF-10A cells (878,000 cells in 6 cm dishes) were transfected with 100 nM ON-TARGETplus siRNA oligo duplexes targeting TP53 (Dharmacon, J-003329-14 and J-003329-15) or Non-Targeting siRNA Control #2 (Dharmacon, D-001810-02) with Oligofectamine transfection reagent (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. EJ-p53 cells (100,000 cells per well in 6-well plates) were transfected with 5 pmol siRNA oligo duplexes using 7.5 μL Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Targeting sequences for TAp73, ΔNp73, and pan-p73 isoforms (Supplementary Table 5) were obtained from the literature [35, 40].

EJ-p53 transient transfection

EJ-p53 cells (630,000 cells in 6 cm dishes) were transfected with 2.21 μg pcDNA3 expression plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed according to the EZChIP kit (Upstate) protocol. Briefly, EJ-p53 cells were plated at 4.5 × 106 cells per 15 cm dish. The cells were then lysed at a final concentration of 2.5 × 107 cells/mL. ChIP lysates were sonicated on ice with 15 cycles of 10 s ON/20 s OFF using a microtip probe with a sonicator (Fisher Sonic Dismembrator). For each IP, 5 μg antibody was added to ~1 × 107 cells of pre-cleared input lysate. The DO-1 p53 mouse monoclonal antibody was used for p53 ChIP, and normal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) was used as a negative control. The DNA was eluted into 50 μL Elution Buffer with the PCR Purification kit (QIAGEN). One μL DNA was assayed by real-time PCR as described above. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Dilutions of the 2% input DNA were used to generate a standard curve.

Results

The human αB-crystallin gene is juxtaposed head-to-head with the related sHSP, HspB2 on chromosome 11q22.3-q23.1. The two genes share an 1111 base pair intergenic promoter that is transcribed in an orientation-dependent fashion to allow for differential gene regulation [41, 42]. In searching the αB-crystallin/HspB2 promoter for DNA binding elements that might be utilized by stress-induced transcription factors, we found a sequence at −199/−169 (relative to the αB-crystallin transcription start site) that closely matches the consensus sequence for a p53 response element (p53RE) (Fig. 1a) [43, 44]. This putative p53RE is highly conserved across mammals and features two p53RE half-sites separated by 11 base pairs which match the consensus sequence at 17/20 bases, including the required cytosines and guanines at positions 4 and 7 in each half-site, respectively. The presence of this putative p53RE in the shared αB-crystallin/HspB2 promoter suggests that αB-crystallin or HspB2 might be transcriptionally regulated by p53.

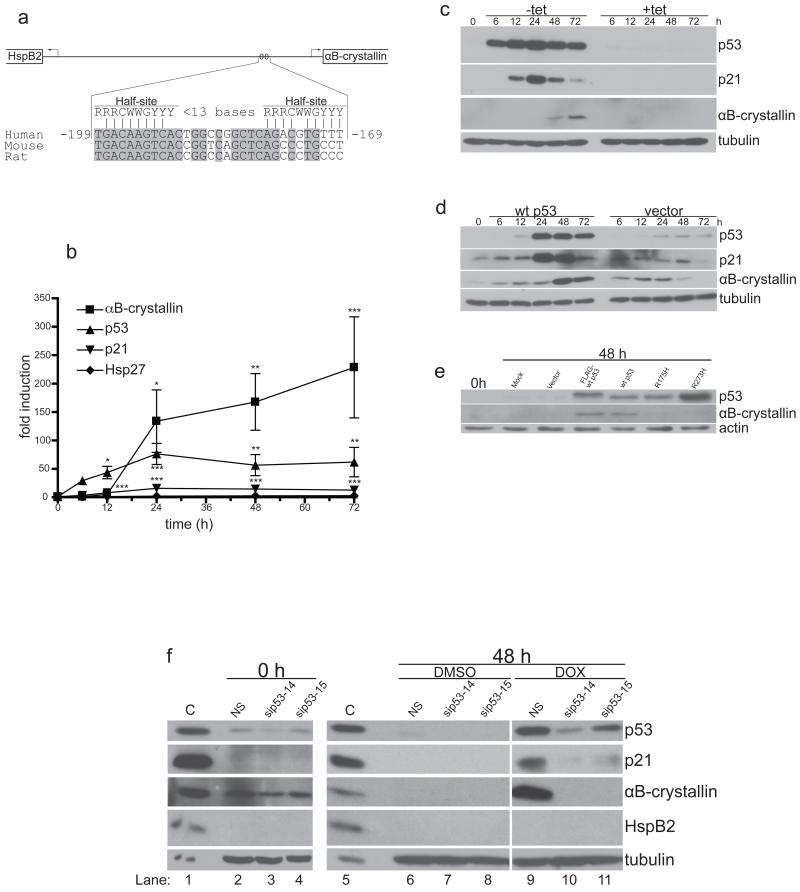

Fig. 1. The shared αB-crystallin and HspB2 promoter contains a putative p53 response element (p53RE) and p53 induces αB-crystallin expression.

(a) Schematic representation of the shared intergenic αB-crystallin and HspB2 promoter. The sequence −199/−169 relative to the αB-crystallin transcriptional start site is shown compared to the p53RE consensus sequence. Vertical lines indicate the base pairs in the human sequence half-sites that match the consensus sequence, and bases conserved among human, mouse, and rat are highlighted in gray. R, purine; Y, pyrimidine; W, A or T. (b) and (c) EJ-p53 cells were grown in the presence or absence of tetracycline, and mRNA and protein were collected at the indicated times. (b) p53 (triangles), p21 (inverted triangles), αB-crystallin (squares), and Hsp27 (diamonds) mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR, and are shown as fold induction relative to the level before induction. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test and is noted for the fold induction value compared to the initial value. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (c) p53, p21, αB-crystallin and tubulin protein levels were assayed by immunoblotting. (d) MCF-10A cells were infected with wild-type p53 or empty pLXSN retrovirus, and protein was collected at the indicated times. p53, p21, αB-crystallin and tubulin levels were determined by immunoblotting. (e) MCF-10A cells were mock infected or infected with empty vector, N-FLAG-tagged wild-type p53, untagged wild-type p53, R175H p53, or R273H p53 pLXSN retrovirus. Forty-eight h later, p53, αB-crystallin and actin protein levels were assayed by immunoblotting. (f) MCF-10A cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting p53 (sip53-14 or sip53-15) or luciferase (NS). Sixteen h later, the cells were treated with 500 nM doxorubicin or DMSO vehicle. Forty-eight h later, p53, p21, αB-crystallin, HspB2 and tubulin expression was determined by immunoblotting. Positive control lysates (C) were used for immunoblotting.

To determine whether αB-crystallin or HspB2 is induced by p53, we utilized an inducible p53 expression system (EJ-p53 cells) in which wild-type p53 expression is induced by tetracycline removal in p53-null human EJ bladder carcinoma cells [36]. Upon removal of tetracycline from the media, p53 and p21 mRNA levels increased rapidly within 12 h (Fig. 1b). Moreover, αB-crystallin mRNA levels were dramatically increased, although the induction of αB-crystallin mRNA, which was first apparent 24 h after tetracycline removal, was delayed compared to that of p53 or p21. Importantly, mRNA levels of the related sHSP Hsp27 were unchanged (Fig. 1b), and HspB2 mRNA levels were at the lower limit of detection or undetectable at all time points examined (data not shown). These results indicate that the αB-crystallin gene is specifically and robustly induced by p53. Immunoblotting of whole cell lysates collected in parallel confirmed rapid p53-dependent induction of p21 protein levels within 12 h and delayed induction of αB-crystallin protein levels within 48 h (Fig. 1c). Similar results were obtained when wild-type p53 was expressed by retroviral transduction in immortalized human MCF-10A breast epithelial cells (Fig. 1d), indicating that the observed induction of αB-crystallin protein by p53 is not cell type-specific. In contrast, retroviral delivery of p53 DNA binding mutants (R175H and R273H) into MCF-10A cells did not induce αB-crystallin protein (Fig. 1e), thereby confirming that the induction of αB-crystallin by p53 is mediated by a transcriptional mechanism. To determine whether genotoxic stress induces αB-crystallin by a p53-dependent mechanism, we transfected MCF-10A cells with two different p53 siRNAs (sip53-14 and sip53-15) or control non-silencing siRNA (NS) targeting luciferase and then treated the cells with the topoisomerase II inhibitor doxorubicin (Fig. 1f). Forty-eight h later, p53, p21 and αB-crystallin protein levels were greatly increased in NS-transfected MCF-10A cells treated with doxorubicin (lane 9) compared to NS-transfected cells treated with DMSO vehicle (lane 6). In contrast, siRNAs targeting p53 (sip53-14 and to a lesser extent sip53-15) partly inhibited p53 induction and dramatically suppressed p21 and αB-crystallin induction by doxorubicin (lanes 10 and 11 vs lane 9). Collectively, these data indicate that p53 is required for αB-crystallin induction in response to genotoxic stress.

We next investigated whether the putative p53RE in the αB-crystallin promoter is transactivated by p53. To this end, EJ-p53 cells were transiently transfected with luciferase reporters containing the full-length αB-crystallin promoter (−1081/+30) or progressive 5′ truncations which contained (−289/+30) or lacked (−171/+30) the putative p53RE (Fig. 2a). In addition, the conserved cytosine and guanine residues in both half-sites of the putative p53RE were mutated in the full-length and −289/+30 truncated promoter constructs; mutation of these sites in p53REs abrogates p53 binding [43]. When p53 was induced in the EJ-p53 cells by tetracycline removal, the full-length and −289/+30 αB-crystallin promoter reporters mediated 10.5- and 7-fold increased luciferase activity, respectively, compared to the promoter-less pGL3-Basic luciferase vector. Mutation of the putative p53RE in the full-length and −289/+30 promoter constructs attenuated p53 transactivation of these reporters. Similarly, deletion of the putative p53RE in the −171/+30 αB-crystallin promoter reporter completely abrogated p53 activation of the promoter. These data demonstrate that p53 activates the αB-crystallin promoter through the putative p53RE.

In order to determine whether p53 binds to the putative p53RE in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed. ChIP with anti-p53 antibodies enriched for p21 5′ p53RE genomic DNA as expected (Fig. 2b), confirming that the ChIP assay worked. In contrast, no enrichment of αB-crystallin promoter genomic DNA was seen. While it is formally possible that p53 may be binding to the αB-crystallin promoter in a manner not detectable by ChIP, this data strongly suggests that p53 does not directly bind to the putative p53RE in the αB-crystallin promoter. Together with the delayed kinetics of αB-crystallin induction by p53 compared to p21 (Figs. 1b and 1c), these results suggest an indirect mechanism of transactivation whereby p53 induces the expression of other target genes, such as p63 or p73, which also bind to p53REs to regulate gene expression.

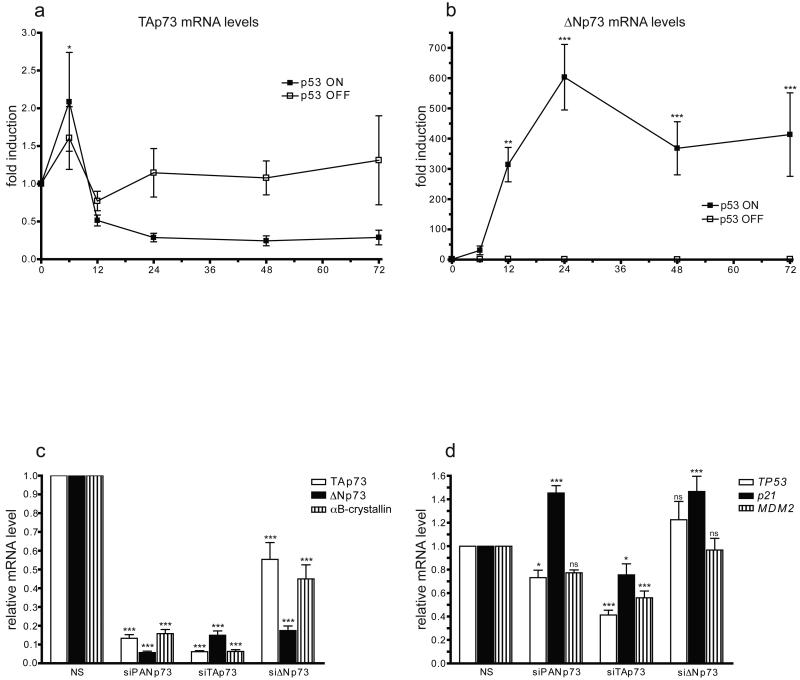

In order to investigate the potential role of the p53 family network in αB-crystallin transactivation, we first determined p63 and p73 mRNA levels following wild-type p53 induction in EJ-p53 cells. TAp63 mRNA levels were initially low and unaffected by p53 induction, while ΔNp63 mRNA levels were undetectable at all time points (data not shown). TAp73 mRNA levels showed a modest transient increase at 6 h with and without p53 induction (Fig. 3a). In contrast, ΔNp73 mRNA levels increased dramatically upon p53 expression (Fig. 3b), consistent with previous reports showing that ΔNp73 is a p53 target gene [20, 45, 46]. The observed induction of ΔNp73 suggests that ΔNp73 may serve as an intermediary factor between p53 expression and αB-crystallin transactivation. To test this hypothesis, we examined the requirement for p73 in the p53-dependent induction of αB-crystallin. Pan p73, TAp73, and ΔNp73 siRNAs inhibited p53 induction of αB-crystallin mRNA levels, indicating that both TAp73 and ΔNp73 are required for p53-dependent transactivation of αB-crystallin (Fig. 3c). Intriguingly, the TAp73 siRNA suppressed ΔNp73 mRNA induction by p53, suggesting that TAp73 is required for p53-mediated ΔNp73 transactivation. Importantly, the p73 siRNAs had modest or no effect on p53, p21, and Mdm2 mRNA levels following p53 induction, indicating that p73 RNAi does not globally disrupt p53-mediated transcription (Fig. 3d). Collectively, these results implicate one or more p73 isoforms in the observed p53-dependent transactivation of αB-crystallin.

Fig. 3. p73 is required for αB-crystallin induction by p53.

(a) and (b) EJ-p53 cells were grown with (filled boxes) or without p53 induction (open boxes), and RNA was collected at the indicated times. TAp73 (a) and ΔNp73 (b) mRNA levels were assayed by real-time RT-PCR, and the mRNA levels are shown normalized to the initial (0 h) level. Statistical significance (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test) is noted at each time point compared to the 0 h mRNA level. (c) and (d) EJ-p53 cells transfected with control non-silencing (NS) siRNA targeting luciferase or siRNAs targeting all p73 isoforms (siPANp73), ΔNp73 (siΔNp73) [35] or TAp73 [40] were re-transfected 24 h later and induced to express p53. RNA was collected 48 h later and mRNA levels were assayed by real-time RT-PCR: (c) TAp73 (open bars), ΔNp73 (filled bars), and αB-crystallin (vertically-striped bars); (d) p53 (open bars), p21 (filled bars), and Mdm2 (vertically-striped bars). The mRNA levels are shown relative to the levels after 48 h of p53 induction in cells transfected with non-silencing siRNA. Statistical significance (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test) is noted for mRNA level differences compared to the level in the non-silencing sample. In (a)-(d), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

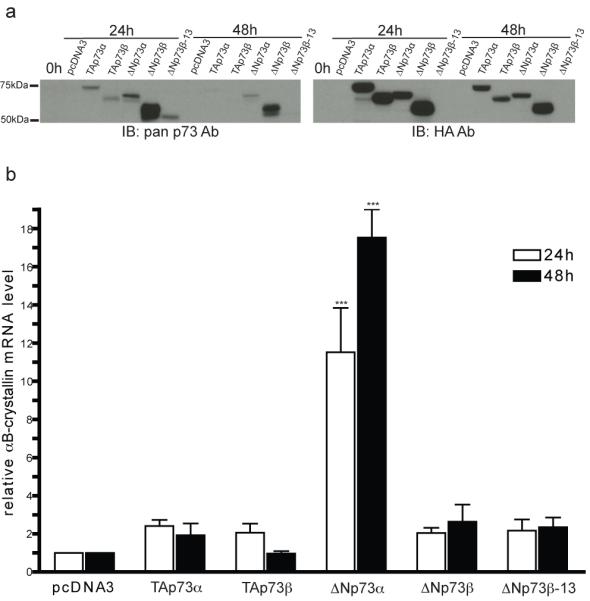

In order to specifically determine which p73 isoform(s) transactivate αB-crystallin, EJ-p53 cells were transiently transfected with N-terminal HA-tagged TAp73α, TAp73β, ΔNp73α, ΔNp73β, and untagged ΔNp73β-13 expression constructs. ΔNp73β-13 lacks the N-terminal 13 amino acids unique to ΔNp73 that are required for transactivation by ΔNp73β [30]. Immunoblotting confirmed that the p73 isoforms are expressed 24 and 48 h after transfection (Fig. 4a). Although ectopic expression of most of the p73 isoforms had little effect on αB-crystallin mRNA levels, ΔNp73α increased αB-crystallin mRNA 11- and 17-fold at 24 and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these data strongly support a model whereby p53 transactivates ΔNp73α which, in turn, induces αB-crystallin expression.

Fig. 4. Ectopic expression of ΔNp73α induces αB-crystallin mRNA.

EJ-p53 cells were transfected with empty vector, HA-TAp73α, HA-TAp73β, HA-ΔNp73α, HA-ΔNp73β, or untagged ΔNp73β-13 (13 amino acid N-terminal truncation) pcDNA3 plasmids. RNA and protein were collected at 0, 24, and 48 h post-transfection. (a) p73 protein levels were assayed by immunoblotting. (b) αB-crystallin mRNA levels 24 h (open bars) and 48 h (filled bars) after transfection were assayed by real-time RT-PCR and normalized to the level in the pcDNA3 empty vector sample at each time point. Statistical significance (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test) is noted for differences compared to pcDNA3 transfection. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

We have demonstrated for the first time that the molecular chaperone αB-crystallin is induced by a novel collaborative relationship among p53 and multiple p73 isoforms. Specifically, p53 leads to the robust transactivation of ΔNp73, which subsequently induces αB-crystallin gene expression by a p53-independent mechanism. Although ΔNp73α is a well-established dominant negative inhibitor of p53 and TAp73 [20, 45, 47], it has also been implicated in p53-dependent and -independent transcriptional regulation of a variety of target genes, including EGR1 and BTG2 [29, 31]. As is the case with αB-crystallin, the mechanisms by which ΔNp73α transactivates these genes is unclear but may involve a direct interaction (e.g., as a transcriptional co-activator) or indirect mechanism (e.g., by repressing a negative transcriptional regulator or activating a positive regulator of the target gene). Interestingly, ectopic expression of ΔNp73α has been reported to induce HSF-1 expression, thereby providing a potential indirect mechanism for αB-crystallin transactivation by ΔNp73α [48]. Our observation that silencing TAp73 inhibits the induction of ΔNp73 by p53 adds another layer of complexity. These results suggest that TAp73 cooperates with p53 to transactivate ΔNp73 in this system, a plausible scenario given that TAp73 itself has been demonstrated to transactivate ΔNp73 [49]. Collectively, our data point to an intricate and tightly coordinated cooperation between p53, TAp73 and ΔNp73 in the transcriptional regulation of αB-crystallin in response to genotoxic stress.

The induction of αB-crystallin, an anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidant protein [4, 6-8], by genotoxic stress may also serve a homeostatic function to suppress apoptosis and reduce ROS levels in the setting of DNA damage. Indeed, recent studies indicate that p53 induces the expression of several pro-survival and anti-oxidant genes, including COX-2, the sestrins, TIGAR, glutathione peroxidase 1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 4 family member A1, and the receptor tyrosine kinase DDR1 [50-55]. Induction of anti-oxidant genes by p53 inhibits tumor initiation by reducing ROS levels, which can cause oxidative DNA damage and promote genomic instability [56]. Transactivation of αB-crystallin downstream of p53 represents a potentially novel mechanism of countering pro-apoptotic and pro-oxidant signaling initiated by genotoxic stress, an hypothesis we will explore in future studies. Intriguingly, αB-crystallin was also recently reported to bind p53 and sequester it in the cytoplasm, suggesting an additional mechanism by which αB-crystallin may inhibit p53 signaling [57].

Our results also provide potentially new insights into the mechanisms of deregulated expression of αB-crystallin in cancer. The cytoprotective function of αB-crystallin has been exploited by diverse cancers, which constitutively express αB-crystallin to overcome apoptosis. For instance, αB-crystallin is aberrantly expressed in apoptosis-resistant triple negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2/ErbB2-negative) breast tumors and glioblastoma multiforme and contributes to their aggressive tumor biology [8, 37, 58]. Furthermore, expression of αB-crystallin correlates with poor survival in several malignancies, including breast cancer, head and neck cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [37, 59-61]. Although p53 is frequently inactivated in cancer, ΔNp73 is commonly expressed in a wide range of clinically aggressive human tumors and is associated with poor outcomes [24-27]. Given the novel link between ΔNp73 and αB-crystallin we have demonstrated, it will be important in future studies to determine whether ΔNp73 and αB-crystallin are co-expressed in human tumors and whether they cooperate in tumor initiation and/or progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Dr. Sam Lee (Harvard Medical School) for providing the EJ-p53 cells and Dr. Xinbin Chen (University of California-Davis) for providing p73 plasmids and advice. These studies were supported by NIH grants R01CA097198 (VLC), R21CA125181 (VLC) and T32CA09560 (JRE), and by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (VLC).

References

- 1.Clark JI, Muchowski PJ. Small heat-shock proteins and their potential role in human disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:52–59. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00048-2. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwitz J. α-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10449–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin JH, Piao CS, Lim CM, Lee JK. LEDGF binding to stress response element increases αB-crystallin expression in astrocytes with oxidative stress. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.029. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehlen P, Kretz-Remy C, Preville X, Arrigo AP. Human hsp27, Drosophila hsp27 and human αB-crystallin expression-mediated increase in glutathione is essential for the protective activity of these proteins against TNFα-induced cell death. EMBO J. 1996;15:2695–2706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haslbeck M, Franzmann T, Weinfurtner D, Buchner J. Some like it hot: the structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:842–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb993. doi: 10.1038/nsmb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein αB-crystallin negatively regulates cytochrome c- and caspase-8-dependent activation of caspase-3 by inhibiting its autoproteolytic maturation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16059–16063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100107200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamradt MC, Lu M, Werner ME, et al. The small heat shock protein αB-crystallin is a novel inhibitor of TRAIL-induced apoptosis that suppresses the activation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11059–11066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413382200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stegh AH, Kesari S, Mahoney JE, et al. Bcl2L12-mediated inhibition of effector caspase-3 and caspase-7 via distinct mechanisms in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10703–10708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712034105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712034105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao YW, Liu JP, Xiang H, Li DW. Human αA- and αB-crystallins bind to Bax and Bcl-Xs to sequester their translocation during staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:512–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401384. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Head MW, Hurwitz L, Goldman JE. Transcription regulation of αB-crystallin in astrocytes: analysis of HSF and AP1 activation by different types of physiological stress. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1029–1039. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh DP, Fatma N, Kimura A, Chylack LT, Jr., Shinohara T. LEDGF binds to heat shock and stress-related element to activate the expression of stress-related genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:943–955. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4887. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swamynathan SK, Piatigorsky J. Regulation of the mouse αB-crystallin and MKBP/HspB2 promoter activities by shared and gene specific intergenic elements: the importance of context dependency. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:689–700. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072302ss. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072302ss. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vousden KH, Lane DP. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontemaggi G, Kela I, Amariglio N, et al. Identification of direct p73 target genes combining DNA microarray and chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43359–43368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205573200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melino G, Bernassola F, Ranalli M, et al. p73 Induces apoptosis via PUMA transactivation and Bax mitochondrial translocation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8076–8083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osada M, Park HL, Nagakawa Y, et al. Differential recognition of response elements determines target gene specificity for p53 and p63. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6077–6089. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6077-6089.2005. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6077-6089.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flores ER, Tsai KY, Crowley D, Sengupta S, Yang A, McKeon F, Jacks T. p63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2002;416:560–564. doi: 10.1038/416560a. doi: 10.1038/416560a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vayssade M, Haddada H, Faridoni-Laurens L, Tourpin S, Valent A, Benard J, Ahomadegbe JC. P73 functionally replaces p53 in adriamycin-treated, p53-deficient breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:860–869. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21033. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitzinger M, Hofmann L, Oswald C, et al. p73 poses a barrier to malignant transformation by limiting anchorage-independent growth. Embo J. 2008;27:792–803. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.13. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grob TJ, Novak U, Maisse C, et al. Human ΔNp73 regulates a dominant negative feedback loop for TAp73 and p53. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:1213–1223. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiewe T, Theseling CC, Putzer BM. Transactivation-deficient ΔTA-p73 inhibits p53 by direct competition for DNA binding: implications for tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14177–14185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200480200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrenko O, Zaika A, Moll UM. ΔNp73 facilitates cell immortalization and cooperates with oncogenic Ras in cellular transformation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5540–5555. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5540-5555.2003. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5540-5555.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozniak CD, Radinovic S, Yang A, McKeon F, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. An anti-apoptotic role for the p53 family member, p73, during developmental neuron death. Science. 2000;289:304–306. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.304. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casciano I, Mazzocco K, Boni L, et al. Expression of ΔNp73 is a molecular marker for adverse outcome in neuroblastoma patients. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:246–251. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400993. doi: 10.1038/sj/cdd/4400993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Concin N, Hofstetter G, Berger A, et al. Clinical relevance of dominant-negative p73 isoforms for responsiveness to chemotherapy and survival in ovarian cancer: evidence for a crucial p53-p73 cross-talk in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8372–8383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uramoto H, Sugio K, Oyama T, Nakata S, Ono K, Morita M, Funa K, Yasumoto K. Expression of ΔNp73 predicts poor prognosis in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6905–6911. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez G, Garcia JM, Pena C, et al. ΔTAp73 upregulation correlates with poor prognosis in human tumors: putative in vivo network involving p73 isoforms, p53, and E2F-1. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:805–815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohn M, Zhang S, Chen X. p63α and ΔNp63alpha can induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and differentially regulate p53 target genes. Oncogene. 2001;20:3193–3205. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kartasheva NN, Lenz-Bauer C, Hartmann O, Schafer H, Eilers M, Dobbelstein M. ΔNp73 can modulate the expression of various genes in a p53-independent fashion. Oncogene. 2003;22:8246–8254. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207138. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu G, Nozell S, Xiao H, Chen X. ΔNp73β is active in transactivation and growth suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:487–501. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.487-501.2004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.487-501.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldschneider D, Million K, Meiller A, Haddada H, Puisieux A, Benard J, May E, Douc-Rasy S. The neurogene BTG2TIS21/PC3 is transactivated by ΔNp73α via p53 specifically in neuroblastoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1245–1253. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01704. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melino G, Lu X, Gasco M, Crook T, Knight RA. Functional regulation of p73 and p63: development and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaruffi P, Casciano I, Masiero L, Basso G, Romani M, Tonini GP. Lack of p73 expression in mature B-ALL and identification of three new splicing variants restricted to pre B and C-ALL indicate a role of p73 in B cell ALL differentiation. Leukemia. 2000;14:518–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Baron V, Mercola D, Mustelin T, Adamson ED. A network of p73, p53 and Egr1 is required for efficient apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:436–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402029. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanza M, Marinari B, Papoutsaki M, Giustizieri ML, D’Alessandra Y, Chimenti S, Guerrini L, Costanzo A. Cross-talks in the p53 family: ΔNp63 is an anti-apoptotic target for ΔNp73α and p53 gain-of-function mutants. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1996–2004. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugrue MM, Shin DY, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. Wild-type p53 triggers a rapid senescence program in human tumor cells lacking functional p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9648–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moyano JV, Evans JR, Chen F, et al. αB-crystallin is a novel oncoprotein that predicts poor clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:261–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI25888. doi: 10.1172/JCI25888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pear WS, Nolan GP, Scott ML, Baltimore D. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8392–8396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong CO, Vidnovic N, DeYoung MP, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. The p63/p73 network mediates chemosensitivity to cisplatin in a biologically defined subset of primary breast cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1370–1380. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rocco JW, Leong CO, Kuperwasser N, DeYoung MP, Ellisen LW. p63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doerwald L, van Rheede T, Dirks RP, et al. Sequence and functional conservation of the intergenic region between the head-to-head genes encoding the small heat shock proteins αB-crystallin and HspB2 in the mammalian lineage. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:674–686. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2659-y. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swamynathan SK, Piatigorsky J. Orientation-dependent influence of an intergenic enhancer on the promoter activity of the divergently transcribed mouse Shsp/αB-crystallin and Mkbp/HspB2 genes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49700–49706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209700200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.el-Deiry WS, Kern SE, Pietenpol JA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat Genet. 1992;1:45–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Funk WD, Pak DT, Karas RH, Wright WE, Shay JW. A transcriptionally active DNA-binding site for human p53 protein complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2866–2871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kartasheva NN, Contente A, Lenz-Stoppler C, Roth J, Dobbelstein M. p53 induces the expression of its antagonist p73 ΔN, establishing an autoregulatory feedback loop. Oncogene. 2002;21:4715–4727. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205584. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vossio S, Palescandolo E, Pediconi N, Moretti F, Balsano C, Levrero M, Costanzo A. ΔN-p73 is activated after DNA damage in a p53-dependent manner to regulate p53-induced cell cycle arrest. Oncogene. 2002;21:3796–3803. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205465. doi: 10.1038/sj/onc/1205465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaika AI, Slade N, Erster SH, Sansome C, Joseph TW, Pearl M, Chalas E, Moll UM. ΔNp73, a dominant-negative inhibitor of wild-type p53 and TAp73, is up-regulated in human tumors. J Exp Med. 2002;196:765–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka Y, Kameoka M, Itaya A, Ota K, Yoshihara K. Regulation of HSF1-responsive gene expression by N-terminal truncated form of p73α. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakagawa T, Takahashi M, Ozaki T, Watanabe Ki K, Todo S, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Nakagawara A. Autoinhibitory regulation of p73 by ΔNp73 to modulate cell survival and death through a p73-specific target element within the ΔNp73 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2575–2585. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2575-2585.2002. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2575-2585.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han JA, Kim JI, Ongusaha PP, Hwang DH, Ballou LR, Mahale A, Aaronson SA, Lee SW. P53-mediated induction of Cox-2 counteracts p53- or genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. Embo J. 2002;21:5635–5644. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf591. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan M, Li S, Swaroop M, Guan K, Oberley LW, Sun Y. Transcriptional activation of the human glutathione peroxidase promoter by p53. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12061–12066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon KA, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. Identification of ALDH4 as a p53-inducible gene and its protective role in cellular stresses. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0122-3. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ongusaha PP, Kim JI, Fang L, Wong TW, Yancopoulos GD, Aaronson SA, Lee SW. p53 induction and activation of DDR1 kinase counteract p53-mediated apoptosis and influence p53 regulation through a positive feedback loop. EMBO J. 2003;22:1289–1301. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg129. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sablina AA, Budanov AV, Ilyinskaya GV, Agapova LS, Kravchenko JE, Chumakov PM. The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nat Med. 2005;11:1306–1313. doi: 10.1038/nm1320. doi: 10.1038/nm1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu S, Li J, Tao Y, Xiao X. Small heat shock protein αB-crystallin binds to p53 to sequester its translocation to mitochondria during hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ivanov O, Chen F, Wiley EL, et al. αB-crystallin is a novel predictor of resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9796-0. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9796-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chelouche-Lev D, Kluger HM, Berger AJ, Rimm DL, Price JE. αB-crystallin as a marker of lymph node involvement in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2543–2548. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20304. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chin D, Boyle GM, Williams RM, et al. αB-crystallin, a new independent marker for poor prognosis in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1239–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000164715.86240.55. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000164715.86240.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang Q, Liu YF, Zhu XJ, Li YH, Zhu J, Zhang JP, Feng ZQ, Guan XH. Expression and prognostic significance of the αB-crystallin gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.09.002. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.