Abstract

The Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE-1) plays a key role in pHi recovery from acidosis and is regulated by pHi and the ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation pathway. Since acidosis increases the activity of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in cardiac muscle, we examined whether CaMKII activates the exchanger by using pharmacological tools and highly specific genetic approaches. Adult rat cardiomyocytes, loaded with the pHi indicator SNARF-1/AM were subjected to different protocols of intracellular acidosis. The rate of pHi recovery from the acid load (dpHi/dt), -an index of NHE-1 activity in HEPES buffer or in NaHCO3 buffer in the presence of inhibition of anion transporters-, was significantly decreased by the CaMKII-inhibitors KN-93 or AIP. pHi recovery from acidosis was faster in CaMKII-overexpressing myocytes than in overexpressing β-galactosidase myocytes, (dpHi/dt: 0.195±0.04 vs. 0.045±0.010 min-1 respectively, n=8), and slower in myocytes from transgenic mice with chronic cardiac CaMKII inhibition (AC3-I) than in controls (AC3-C). Inhibition of CaMKII and/or ERK1/2 indicated that stimulation of NHE-1 by CaMKII was independent of and additive to the ERK1/2 cascade. In vitro studies with fusion proteins containing wild-type or mutated (Ser/Ala) versions of the C-terminal domain of NHE-1, indicate that CaMKII phosphorylates NHE-1 at residues other than the canonical phosphorylation sites for the kinase (Ser648, Ser703 and Ser796). These results provide new mechanistic insights and unequivocally demonstrate a role of the already multifunctional CaMKII on the regulation of the NHE-1 activity. They also prove clinically important in multiple disorders which, like ischemia/reperfusion injury or hypertrophy, are associated with increased NHE-1 and CaMKII.

Introduction

The control of intracellular pH (pHi) is a fundamental process common to all eukaryotic cells required to preserve normal cell function. In cardiac myocytes as well as in other cell types, acid and its equivalents are generated metabolically within the cell. This continuous acid production, coupled to the fact that the negative membrane potential favors proton leakage into the cell, would result, in the absence of the appropriate regulation, in a decrease in pHi from its resting level of about 7.1. A number of pHi regulatory proteins exist as integral parts of the plasma membrane to remove excess acid. One of them, the type 1 isoform of the Na+-H+ exchanger, (NHE-1), is the major mechanism of proton removal from cardiac myocytes under conditions of marked intracellular acidosis (1]. Experimental evidence indicates that besides its critical role in the regulation of pHi [2, 3], the NHE-1 is also involved in pathological processes, as a mediator of myocardial hypertrophy [2, 3] or in the pathogenesis of tissue damage during ischemia/reperfusion [4]. The NHE-1 consists of an N-terminal membrane domain that functions to transport ions, and a C-terminal cytosolic regulatory domain that regulates its activity and mediates cytoskeletal interactions. The distal region of this C-terminal tail contains a number of serine and threonine residues that are targets for several protein kinases. Among these, the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90rsk), seem to play a key role in the activation of NHE-1 by growth factors [5], hormones [6-8] and stretch [9] as well as by ischemia/reperfusion injury [10] and sustained acidosis [11-13]. Moreover, recent experiments have shown that NHE-1 is also a novel target for protein kinase B (PKB), whose activation phosphorylates and inactivates the exchanger [14]. Another kinase that has been reported to phosphorylate the C-terminal domain of the NHE-1 in vitro is the Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein-kinase (CaMKII) [15]. This is particularly interesting in the context of evidence provided by different laboratories, including our own, supporting a role of CaMKII activation in the mechanical recovery that occurs following the initial decrease in contractility produced by an acid and/or ischemic insult [16-22]. However, the putative functional role of CaMKII in the regulation of NHE-1 activity in vivo is not completely clear and the impact of CaMKII on NHE-1 activity is still held as a question mark in a recent review on NHE-1 regulation [3]. Using pharmacological tools, studies from Le Prigent et al. [23] and Moor et al., [24] support a role of CaMKII on NHE-1. In contrast results of Komukai et al, failed to show a regulation of NHE-1 by this kinase [16]. The present experiments were undertaken to further examine whether CaMKII modulates the activity of the NHE-1 in isolated myocytes during intracellular acidosis and, if so, to establish whether this regulation occurs independently of the ERK1/2-p90rsk cascade, potentially through direct phosphorylation of the exchanger by CaMKII. Since CaMKII-regulation of NHE-1 is likely to be physiologically and pathophysiologically important, we have used highly precise genetic approaches (adenoviral gene transfer and transgenic mice), to more specifically manipulate CaMKII activity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Collagenase type B was from Worthington Biochemical Corp. (Lakewood, NJ, USA), SNARF-1 AM from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR, USA). KN-93, AIP and PD98059 were from Calbiochem. Antibodies used were phospho-CaMKII (Abcam), GAPDH (ABR), phospho-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Adenovirus expressing CaMKII and βgal were generously given by Roger Hajjar's laboratory (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York).

Animals and myocyte isolation

Wistar rats (200-300 g) and transgenic mice with cardiomyocyte-delimited transgenic expression of either a CaMKII inhibitory peptide (AC3-I) or a scrambled control peptide (AC3-C) were used [25]. The mice, originally obtained from Mark Anderson's laboratory (University of Iowa, USA), were reproduced and genotyped as described in Suplementary data (Figure 1). All animals used in this study were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No.85-23, revised 1996). Rat and mice myocytes were isolated by enzymatic digestion as previously described [26] and kept in a HEPES buffered solution at room temperature (20-22 °C), until used.

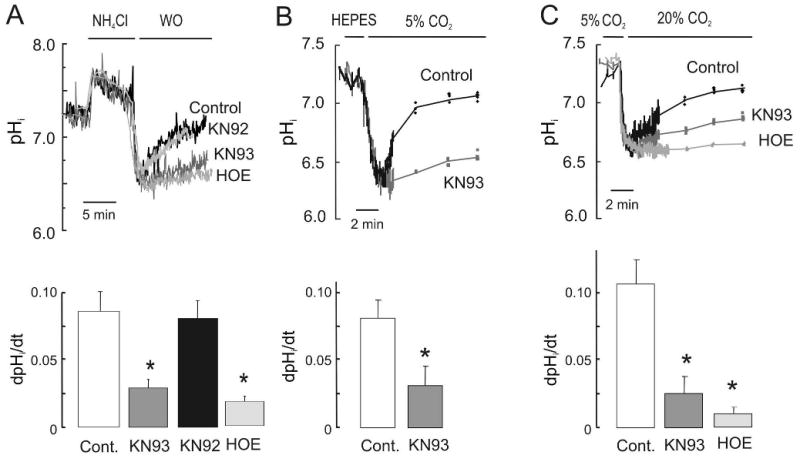

Figure 1. CaMKII-inhibition decreased the activity of NHE-1 during acute acidosis.

Representative superimposed recordings of pHi and overall results of adult rat isolated myocytes loaded with SNARF-1/AM and subjected to acute intracellular acidosis induced by: (A) transient exposure to 20 mM NH4Cl in HEPES buffer; (B) substitution of HEPES by NaHCO3 buffer and (C) hypercapnia at constant pHo in NaHCO3 buffer in the presence of SITS. Protocols were performed either in the absence of drug (Control, Cont.) or in the presence of 1 μM KN93, its inert analogue KN92 or 3 μM of HOE642 (n=5 cells per group). NHE-1 activity was estimated from the rate of change in pHi (dpHi/dt) during the recovery at an identical pHi of 6.8. In B and C, note that after the continuous pHi recording, measurements of pHi were performed every 2 min. In this and the following Figures overall results are expressed as mean ± SE. * p<0.05 vs Cont.

Recombinant adenoviruses and cell transfection

Two first-generation type 5 recombinant adenovirus were used. Ad.βgal carrying the β-galactosidase and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) genes and Ad.CaMKII carrying both, the CaMKIIδC and the GFP genes, each under separate cytomegalovirus promoters. After isolation, cells resuspended in DMEM and plated at a density of 5×104 cells/ml, were infected with adenoviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 and cultured for 48h. The verification of the transgene expression was monitored by GFP fluorescence at an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and western blotting.

Intracellular pH (pHi) measurements

Myocytes were loaded with the membrane-permeable acetoxymethyl ester form of the fluorescent H+-sensitive indicator SNARF-1/AM. pHi measurements and calibration were performed as previously described [26].

Induction of intracellular acidosis

Intracellular acidosis was induced by different methods: 1. NH4Cl pulses (4 min) in HEPES or NaHCO3 buffer in the presence of 100 μM of the anion blocker SITS; 2. Replacement of HEPES buffer by NaHCO3 buffer + SITS and 3. Replacement of the NaHCO3 solution +SITS by a similar solution in which CO2 of the gas mixture and NaHCO3 were simultaneously increased to 20% and 80 mM, respectively to keep extracellular pH constant at 7.4 [27] (Details of the different protocols used are provided in Supplementary data). The rate of pHi recovery from the acid loading (dpHi/dt), estimated as previously described [28] at a fixed pHi of 6.8 and the of H+-efflux rate (JH+), calculated as the product of dpHi/dt and the intrinsic buffering capacity [14], were used as indexes of NHE-1 activity. When CaMKII and MEK inhibitors were used, they were added 10 min before the induction of intracellular acidosis. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Western Blotting

For immunological detection of phospho-CaMKII, phospho-Thr17-PLN, phosphor-Ser16-PLN and phospho-ERK1/2 and their respective non-phosphorylated forms, 20-50 μg of rat/mouse homogenate proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore) and probed with appropriate primary antibodies. Bound antibody was detected by labelling with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham). The signal intensity of the bands on the film was quantified using Image J based on NIH Image.

CaMKII-Mediated Phosphorylation of NHE-1 in vitro

In vitro kinase assays were performed with glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-NHE-1 fusion protein comprising amino acids 625-815 of human NHE-1, wild type or with all three canonical phosphorylation sites for CaMKII (Ser648, Ser703, and Ser796) mutated to Ala as previously described [14], except that 100 U pre-actived CaMKII (New England Biolabs) were used. Proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and phosphorylation assessed by autoradiography (32P). When phosphorylating the mutated GST-NHE-1, comparison was made with an in vitro phosphorylation, using active PKBα (PH domain deletion mutant) [14].

Statistics

Data are expressed as the means ± SE. Student's paired t test or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t test was used for intra-group comparison or comparison among groups, respectively. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

CaMKII activity contributes to NHE-1-mediated pHi recovery from acidosis

Intracellular acidosis, a situation in which acid extruder mechanisms are fully stimulated, is known to promote the activation of CaMKII [16, 17, 19, 20]. To assess the potential functional significance of CaMKII activation on NHE-1 function during an acid load, we investigated the consequences of pharmacological inhibition of CaMKII on the rate of pHi recovery in SNARF-1/AM loaded isolated rat adult myocytes after exposure to an NH4Cl pulse. Washout of NH4Cl with HEPES buffer was performed either immediately (acute acidosis) or after 5 min of incubation with the NHE-1 inhibitor HOE642, to preclude NHE-1 activity (sustained acidosis). Figure 1A shows superimposed recordings of pHi during the acute acidosis protocol. Removal of NH4Cl produced a rapid decrease in pHi followed by its recovery, that was prevented by HOE642. Pre-treatment of the myocytes with the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 markedly reduced the rate of pHi recovery from the acid load when compared to myocytes either subjected to intracellular acidosis in the absence of KN-93 (Control) or pre-treated with the inert analogue, KN-92. KN-93 failed to affect pHi recovery in the presence of HOE642, indicating that the effects of CaMKII on pHi recovery occurs through the regulation of NHE-1 activity (See Figure 2 of on line Supplementary data). The NHE-1-modulatory effect of CaMKII during acute acidosis was further tested in two additional protocols: 1) Substitution of HEPES by NaHCO3 buffer at the same pHo (7.4) (Figure 1B) and 2) Hypercapnia induced by simultaneously increasing NaHCO3 and CO2 to keep pHo (Figure 1C). In both cases, the initial rapid decrease in pHi was followed by a pHi recovery, which was slower in the presence of KN-93.

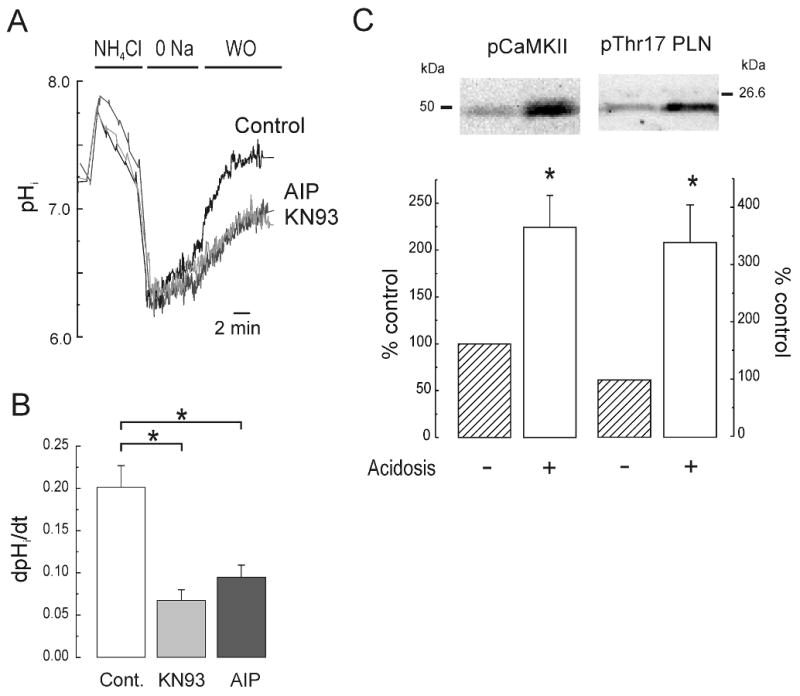

The role of CaMKII was also investigated during sustained acidosis (Figure 2). In this case, two structurally unrelated CaMKII inhibitors were used: KN-93 and the more specific AIP. Superimposed records and overall results shown in Figure 2A and B indicate that the presence of either KN-93 or AIP significantly decreased the rate of pHi recovery after the sustained acid load. In all cases NHE-1 activity was measured at an identical pHi of 6.8 to preclude any confounding effect of allosteric regulation of the NHE-1 by pHi. Thus, it seems reasonable to assume that the differences observed are due to the activity of the kinases explored.

Figure 2. CaMKII-inhibition decreased the activity of NHE-1 during sustained acidosis.

Representative superimposed recordings of pHi (A) and overall results (B) of adult rat isolated myocytes subjected to sustained intracellular acidosis induced by exposure to 20 mM NH4Cl followed by its washout with a Na+-free solution. Normal [Na+]o was then reintroduced to release NHE-1 blockade and permit pHi recovery. The protocol was performed either in the absence of drugs (Cont., n=6) or in the presence of 1 μM KN93 (n=5) or AIP (n=4). NHE-1 activity was estimated as in Figure 1. (C) Immunoblots and overall results of the effects of acidosis on the phosphorylation of CaMKII and its substrate Thr17 of phospholamban (PLN) (n=4-8 hearts per group). * p<0.05 vs Cont.

To confirm the activation of CaMKII during intracellular acidosis, the phosphorylation of the kinase and of its substrate phospholamban (PLN) was measured in isolated myocytes subjected to an NH4Cl pulse. Acidosis promoted phosphorylation of CaMKII and of PLN at Thr17, the specific CaMKII phosphorylation site (Figure 2C).

Taken together these results indicate that acidosis-induced increase in CaMKII activity enhances NHE-1 function during both acute and sustained intracellular acidosis.

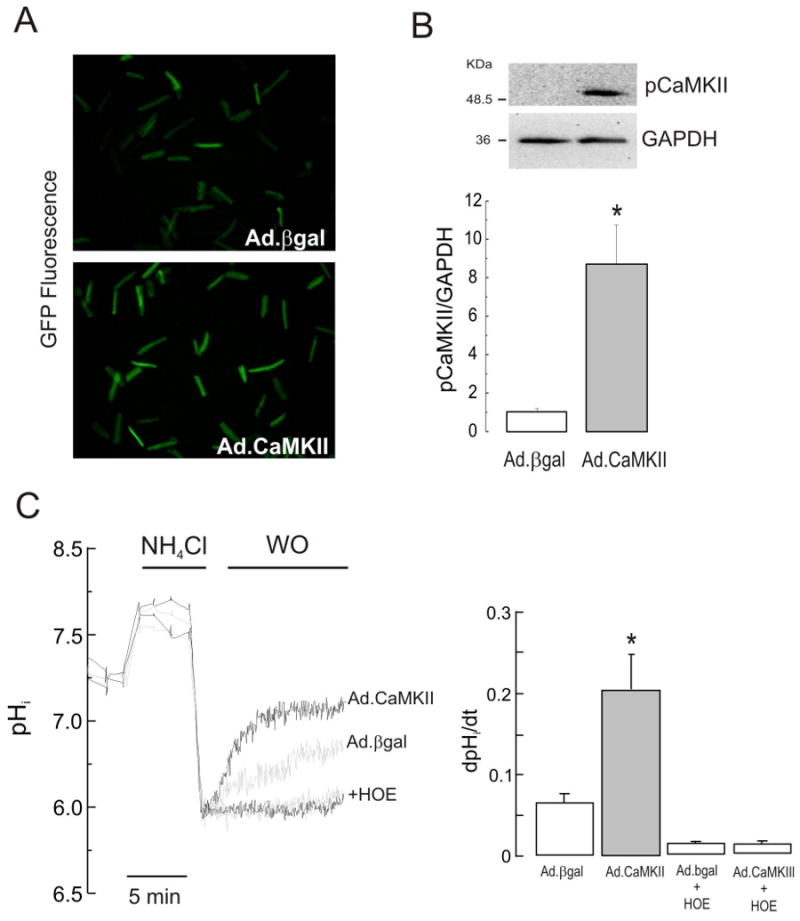

CaMKII overexpression increases the rate of pHi recovery from intracellular acidosis

The NHE-1 modulatory effect of CaMKII was further tested in experiments in rat isolated myocytes overexpressing CaMKII or β-galactosidase (βgal), which serve as controls. After 48 h of incubation, 100% of rod-shaped myocytes, infected with either Ad.βgal or Ad.CaMKII viruses, presented a robust expression of the reporter gene GFP, visualized by fluorescent microscopy (Figure 3A). At this time, CaMKII expression was significantly increased, as confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 3B). There were no significant differences between infected groups in the basal pHi and the degree of intracellular acidosis achieved after NH4Cl washout (see Table I). Figure 3C shows that CaMKII-overexpressing myocytes presented a faster pHi recovery from acute intracellular acidosis than βgal-overexpressing myocytes. The enhanced rate of pH recovery showed by CaMKII-overexpressing myocytes was completely prevented by inhibition of NHE-1, a result that directly implicates NHE-1 in the effects of CaMKII. Of note, the βgal-overexpressing myocytes presented a slightly slower rate of pHi recovery when compared to freshly isolated, non-infected myocytes (Figure 3C versus 1A). In spite of this, the rate of pHi recovery in CaMKII-overexpressing myocytes was even faster than that observed in fresh myocytes subjected to an NH4Cl pulse (Figure 3C versus 1A).

Figure 3. Overexpression of CaMKII enhanced the rate of pHi recovery in isolated myocytes submitted to an acid load.

(A) After 48 h of infection, fluorescent myocytes indicated the successful expression of β-galactosidase and CaMKIIδC genes. (B) Representative blots and overall results of phospho-CaMKII and GAPDH confirmed the overexpression of CaMKII in Ad.CaMKII vs. Ad.βgal infected cells (n=6 in both groups). (C) In CaMKII overexpressing cells, the recovery of pHi was faster than in βgal overexpressing cells. Inhibition of NHE-1 by HOE, completely blocked the pHi recovery in both, CaMKII and βgal overexpressing cells. Black and grey traces depict CaMKII and βgal-overexpressing myocytes respectively in the absence and presence of the NHE-1 inhibitor. Data of 6 independent experiments from 6 hearts. *p<0.05 vs. Ad.βgal.

TABLE I. Basal and minimum pHi values obtained in isolated rat myocytes used in the gain-of function studies and in isolated mouse myocytes used in the loss-of-function studies.

| Basal pHi | Minimal pHi | |

|---|---|---|

| βgal-overexpressing myocytes (n=8) | 7.31±0.06 | 6.59±0.05 |

| CaMKII-overexpressing myocytes (n=8) | 7.37±0.08 | 6.63±0.05 |

| Control WT myocytes (n=8) | 7.33 ±0.05 | 6.40 ± 0.06 |

| AC3-C myocytes (n= 10) | 7.35±0.06 | 6.45±0.06 |

| AC3-I myocytes (n=6) | 7.32±0.05 | 6.45±0.06 |

These results suggest that increased CaMKII activity results in a significant increase in sarcolemmal NHE-1 activity in response to intracellular acidosis and further confirm the role of CaMKII activity in the pHi recovery from an acid load.

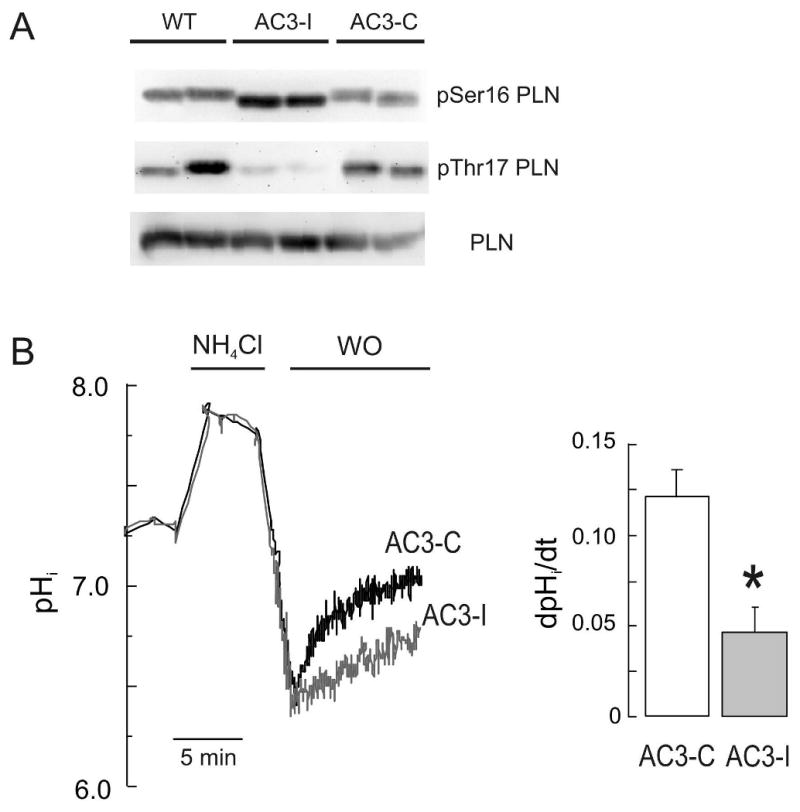

Chronic inhibition of CaMKII reduces the rate of pHi recovery from intracellular acidosis

To further determine the role of endogenous CaMKII activity in the activation of NHE-1 during acidosis, we used cardiomyocytes from mice with chronic cardiac CaMKII inhibition by expression of a specific CaMKII inhibitory peptide (AC3-I), as well as from a transgenic control mouse with an inactive scrambled version of AC3-I, AC3-C. Mice carrying these peptides were identified by PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from mouse tails (Figure 1 Supplementary data). The CaMKII inhibition of AC3-I mice was confirmed by the reduced CaMKII-dependent PLN phosphorylation in AC3-I cardiac homogenates compared to AC3-C and WT (Figure 4A), consistent with previous results [25]. Isolated AC3-I and AC3-C myocytes as well as WT littermate cells, exhibited no alteration of basal pHi and the degree of intracellular acidosis achieved after NH4Cl washout (Table I). However the rate of pHi recovery after the acid load was significantly depressed in AC3-I myocytes when compared to AC3-C myocytes (Figure 4B). Taken together, our complementary gain-of-function and loss-of-function data indicate that CaMKII increases NHE-1 activity during intracellular acidosis in cardiac myocytes.

Figure 4. Chronic inhibition of CaMKII decreased the rate of pHi recovery from an acid load.

(A) Analysis of phospholamban (PLN) expression and basal phosphorylation of Ser16 and Thr17 sites of PLN, in AC3-I, AC3-C and WT mice. (B) Representative superimposed recordings of pHi and overall results obtained in myocytes isolated from adult mice with chronic cardiac CaMKII inhibition (AC3-I) and their transgenic controls AC3-C. Data from 10 and 6 cells in AC3-C and AC3-I, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. AC3-C.

Stimulation of NHE-1 by CaMKII is independent of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway

It has been previously shown that activation of the NHE-1 during sustained acidosis is potentiated by the MAP kinase pathway (ERK1/2 and p90rsk) [11, 12]. We therefore investigated whether CaMKII modulates the activity of the exchanger during sustained acidosis through the activation of the MAP kinase cascade or independently of this pathway. Figure 5A shows a representative immunoblot and overall results indicating that the sustained acidosis-induced increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation was not modified by the CaMKII inhibitors, KN-93 or AIP. As expected, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was undectable in the presence of 30 μM PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK, the upstream activator of ERK1/2, as well as by the combination of PD98059 and KN-93. To assess the contribution of both phosphorylation pathways to the stimulation of NHE-1, we performed experiments in isolated myocytes subjected to sustained acidosis in the presence and absence of KN-93 and PD98059, added either independently or simultaneously. Figure 5B and C shows superimposed typical records and mean H+ fluxes (JH+), respectively, of these experiments. Independent inhibition of either CaMKII or ERK1/2 pathways similarly reduced NHE-1 activity. Combination of both inhibitors produced a further and significant decrease in pHi recovery. These results indicate that CaMKII stimulation of NHE-1 during sustained acidosis is independent of the ERK1/2 pathway and that, when acting together, both phosphorylation cascades have additive effects. Moreover during acute acidosis, CaMKII appears to participate as the only functional kinase pathway stimulating NHE-1 activity, since inhibition of the MAP kinase cascade with PD98059 had no significant effect on pHi recovery from an acute acid load, in agreement with previous findings [11, 13] (see Figure 3 of Supplementary data).

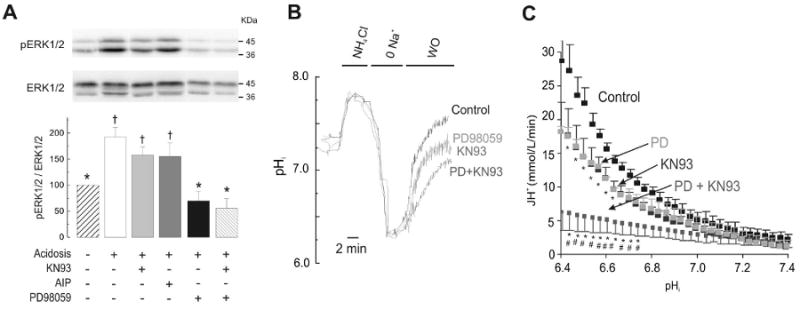

Figure 5. CaMKII-dependent activation of NHE-1 is independent of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.

(A) Immunoblots and overall results of sustained acidosis-induced increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was studied in the absence and the presence of the CaMKII inhibitors, KN93 or AIP (1 μM), MEK inhibitor PD98059 (30 μM, PD) and the combination PD+KN93 (n=4-17 hearts per group). (B) Superimposed typical pHi records (C) and overall results (n=4-6 cells per group) of the experiments described in (A). H+ efflux (JH+) as an index of NHE-1 activity was calculated as product of the recovery rate (dpHi/dt) and the intrinsic buffering capacity (βi).* p<0.05 with respect to control. # p<0.05 with to PD or KN-93.

CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of NHE-1

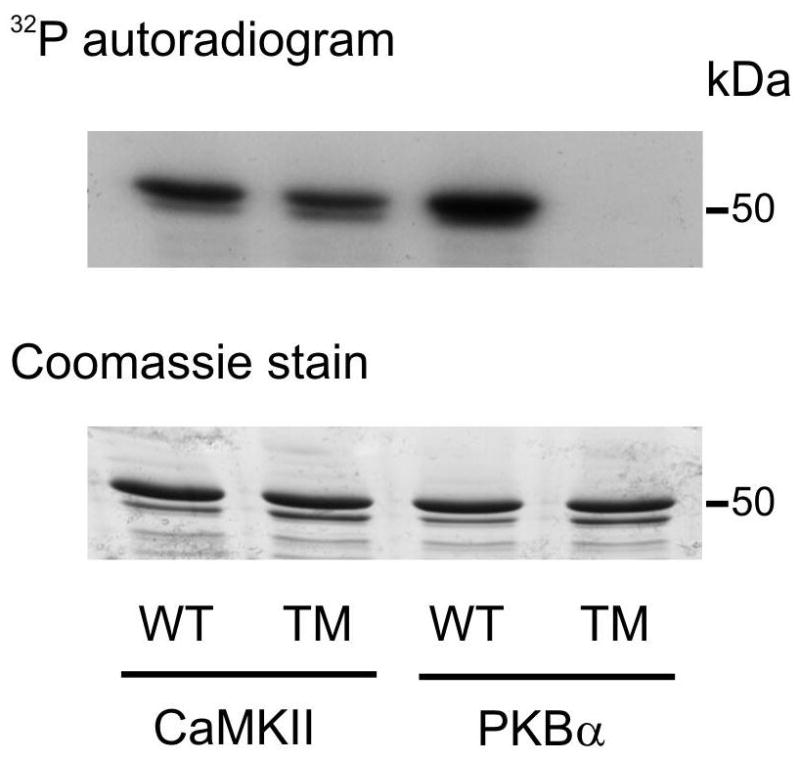

The carboxyl-terminal regulatory domain of NHE-1 contains 3 sites that conform to the optimal CaMKII phosphorylation motif RXXS/T [29] namely Ser648 (RLRS), Ser703 (RIGS), and Ser796 (RCLS). Therefore, we determined whether active CaMKII could phosphorylate a recombinant NHE-1 fusion protein (GST-NHE-1) encompassing the final 190 amino acids (625–815) of the carboxyl-terminal regulatory domain of human NHE-1, in an in vitro kinase assay using 32P-labeled ATP. We used the fusion protein either in wild-type (WT) form or with all three canonical phosphorylation sites for CaMKII mutated to a non-phosphorylatable alanine (Ser648/703/796Ala). The autoradiogram revealed CaMKII-mediated 32P incorporation into both WT and Ser648/703/796Ala NHE-1 fusion proteins (Figure 6). Of note, PKBα, a kinase that has been recently shown to phosphorylate NHE-1 predominantly at Ser648 but also at Ser703 and Ser796 in vitro [14], phosphorylated the WT substrate but failed to phosphorylate the triple mutant, indicating distinct site specificity of the two NHE-1 kinases. These pilot experiments are in agreement with previous findings obtained with a substrate protein comprising the final 178 amino acids of rabbit NHE-1 [15] and additionally indicate that CaMKII phosphorylates the carboxyl-terminal regulatory domain of human NHE-1 at sites outside the canonical sequences for CaMKII phosphorylation around Ser648, Ser703 and Ser796.

Figure 6. In vitro phosphorylation of the carboxyl terminal of NHE-1.

Phosphorylation of wild type (WT) GST-NHE1(625-815) fusion protein or GST-NHE1 fusion protein in which Ser648/703/796 were replaced by Ala (triple mutant, TM) by preactivated CaMKII or protein kinase Bα (PKBα) detected by 32P incorporation and autoradiography (top panel). Equal protein loading was confirmed by Coomassie staining (bottom panel). Similar results were obtained in two other experiments.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that activation of CaMKII during acidosis enhances the activity of the NHE-1 and in doing so, contributes to the pHi recovery from an acid load. By the use of highly specific genetic approaches (adenoviral gene transfer and transgenic mice) that allow a precise manipulation of CaMKII activity, the present observations definitively supports the regulation of NHE-1 in the heart by the multifunctional CaMKII. The results further showed that CaMKII phosphorylates in vitro the C-terminal domain of NHE-1. This phosphorylation occurs at sites that are distinct from the canonical consensus sites. Finally, our findings clearly established that this CaMKII-dependent activation of NHE-1 occurs independently of the ERK1/2 pathway.

CaMKII-dependent activation of the NHE-1

The present experiments clearly show that pHi recovery from an acid load occurred in association with a significant increase in CaMKII activity as reflected by an increase in the autophosphorylation of the kinase and the phosphorylation of Thr17 site of PLN, one of the most typical CaMKII substrates. Moreover, inhibition of CaMKII by KN-93 or by the more specific peptide AIP, decreased the rate of pHi recovery from acute and sustained intracellular acidosis, evoked by different approaches. Control experiments showed that CaMKII-inhibition of pHi recovery does not occur in the presence of NHE-1 blockade. Taken together, these results indicate that CaMKII enhances the activity of NHE-1. This conclusion is fully supported by the complementary gain and loss-of-function experiments in which CaMKII was either overexpressed or chronically inhibited (AC3-I mice).

Previous experiments where the possible CaMKII-mediated activation of the NHE-1 was explored, are controversial. Experiments by Le Prigent et al., [23] described a decrease in the acidosis-induced activity of the NHE-1 after treatment with the CaMKII-inhibitor KN-62 in a study in diabetic rats. Moor et al., [24] could only achieve a decrease in NHE-1 activity in neonatal myocytes with a rather high concentration of the inhibitor KN-93 (10 μM). Finally, a CaMKII-mediated activation of NHE-1 could not be demonstrated by Komukai et al., [16]. The present data consistently show, by means of two non-related pharmacological inhibitors as well as by gain and loss-of-function experiments, that inhibition and upregulation of CaMKII diminished and enhanced, respectively, the activity of the NHE-1. Importantly, these results provide new mechanistic insights and unequivocally demonstrate a role of the already multifunctional CaMKII on the regulation of the NHE-1 activity.

CaMKII-dependent NHE-1 activation does not involve the MAPK pathway

Numerous studies in different cell types assign a key role to the ERK1/2 arm of the MAPK cascade, in the regulation of NHE-1 activity by different stimuli, including sustained acidosis [5-13]. In this scenario, a mandatory question is then whether CaMKII and ERK1/2 constitute two different steps of the same pathway that regulates the NHE-1 or whether they are part of different and independent cascades. Our results show that CaMKII and ERK1/2 pathways are independent and when acting together, they have an additive effect. Further support to the independence of both signaling cascades is given by the finding that during acute acidosis only the CaMKII cascade and not the ERK1/2 pathway, has functional effects on NHE-1 activity.

CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of NHE-1

Earlier experiments established that the NHE-1 is modulated by extracellular Ca2+, i.e. increasing Ca2+ induces the stimulation of the exchanger [30, 31]. Ca2+ regulation of the NHE-1 can be accomplished by at least two different pathways: direct binding of Ca2+/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM) or CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation. Both possibilities have some experimental support. It has been reported that NHE-1 is a Ca2+/CaM binding protein in fibroblast [30] and that direct binding of Ca2+/CaM to the NHE-1 stimulates the exchanger [31]. Moreover, Fliegel et al. [15], demonstrated that purified CaMKII in vitro phosphorylated a fusion protein containing the C-terminal domain of the NHE-1. It was suggested that this phosphorylation could occur at any of the three consensus sequences for CaMKII which correspond to amino acids Ser648, Ser703 and Ser796 [15]. However, no attempts were made in this earlier work to identify the putative CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation sites of the NHE-1. The present experiments clearly showed that although CaMKII phosphorylates the C terminal domain of the NHE-1, this phosphorylation occurs at non-canonical sites. Although there are no other residues in the C terminal domain of the NHE-1 which conform to the optimal target sequence of CaMKII (RXXS), this result was not entirely unexpected since different studies have reported “non-arginine requiring” substrates for CaMKII [32]. These findings open a wide range of possibilities to be envisaged to map the aminoacid residue(s) phosphorylated by CaMKII. Experiments in our laboratory are currently underway to explore this issue. In this scenario, it is important to acknowledge however that our data does not prove that the effect of CaMKII on pHi regulation occurs in vivo through the direct phosphorylation of NHE-1 and intermediary CaMKII substrates may be involved in NHE-1 regulation. A direct NHE-1 phosphorylation in CaMKII-mediated regulation of NHE-1 activity, remains to be determined.

Functional Implications

The present findings support a mechanism by which CaMKII-activation could contribute to enhance NHE-1 activity during acidosis, playing a beneficial function in the spontaneous mechanical recovery that occurs after lowering pHi. Moreover, since acidosis is a major component of ischemia, our results are consistent with the possibility that CaMKII induced NHE-1 activation participates in the overdrive of pHi regulation that occurs during reperfusion and leads to electrical arrythmias and myocardial injury [33, 34]. Furthermore, the NHE-1 is implicated in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure [35] where CaMKII has also been shown to be upregulated [36, 37]. Thus, our results may provide new information or a potential involvement of CaMKII-dependent NHE-1 activation in the development of hypertrophy and the evolution from hypertrophy to heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Monica Rando for excellent technical assistance. We are also indebted to Mark E. Anderson and Roger Hajjar for their generous gifts of the original AC3-I and -C transgenic mice and the adenovirus expressing CaMKII, respectively. M.V-P., C.M-W., A.M. are established investigators of CONICET, Argentina. C.A.V. and A.M.H. are fellows from CONICET and N.L. has a fellowship from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica (ANPCyT). This work was supported by the ANPCyT PICT 1321 to C.M-W., and ANPCyT PICT 26117, CONICET PIP 5300 and 2139, Fogarty Grant # RO3TW07713 to A.M.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Martín Vila-Petroff, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina.

Cecilia Mundiña-Weilenmann, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina.

Noelia Lezcano, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina.

Andrew K. Snabaitis, Cardiovascular Division, King's College London, The Rayne Institute, St Thomas' Hospital, London SE1 7EH, United Kingdom

Maria Ana Huergo, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina.

Carlos A. Valverde, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina

Metin Avkiran, Cardiovascular Division, King's College London, The Rayne Institute, St Thomas' Hospital, London SE1 7EH, United Kingdom.

Alicia Mattiazzi, Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, CCT-La Plata CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 60 y 120 (1900) La Plata, Argentina.

References

- 1.Leem CH, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Vaughan-Jones RD. Characterization of intracellular pH regulation in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. J Physiol. 1999;517:159–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0159z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cingolani HE, Ennis IL. Sodium-hydrogen exchanger, cardiac overload, and myocardial hypertrophy. Circulation. 2007;115:1090–100. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.626929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaughan-Jones RD, Spitzer KW, Swietach P. Intracellular pH regulation in heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:318–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avkiran M, Gross G, Karmazyn M, Klein H, Murphy E, Ytrehus K. Na+/H+ exchange in ischemia, reperfusion and preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:162–6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi E, Abe J, Gallis B, Aebersold R, Spring DJ, Krebs EG, Berk BC. p90(RSK) is a serum-stimulated Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1 kinase. Regulatory phosphorylation of serine 703 of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20206–214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunasegaram S, Haworth RS, Hearse DJ, Avkiran M. Regulation of sarcolemmal Na+/H+ exchanger activity by angiotensin II in adult rat ventricular myocytes: opposing actions via AT(1) versus AT(2) receptors. Circ Res. 1999;85:919–30. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snabaitis AK, Yokoyama H, Avkiran M. Roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases and protein kinase C in alpha(1A)-adrenoceptor-mediated stimulation of the sarcolemmal Na+/H+ exchanger. Circ Res. 2000;86:214–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuello F, Snabaitis AK, Cohen MS, Taunton J, Avkiran M. Evidence for direct regulation of myocardial Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 phosphorylation and activity by 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK): effects of the novel and specific RSK inhibitor fmk on responses to alpha1-adrenergic stimulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:799–806. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cingolani HE, Alvarez BV, Ennis IL, Camilión de Hurtado MC. Stretch-induced alkalinization of feline papillary muscle: an autocrine-paracrine system. Circ Res. 1998;83:775–80. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moor AN, Gan XT, Karmazyn M, Fliegel L. Activation of Na+/H+ exchanger-directed protein kinases in the ischemic and ischemic-reperfused rat myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16113–122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haworth RS, McCann C, Snabaitis AK, Roberts NA, Avkiran M. Stimulation of the plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 by sustained intracellular acidosis. Evidence for a novel mechanism mediated by the ERK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31676–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haworth RS, Dashnyam S, Avkiran M. Ras triggers acidosis-induced activation of the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase pathway in cardiac myocytes. Biochem J. 2006;399:493–501. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malo ME, Li L, Fliegel L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger is mediated through phosphorylation of amino acids Ser770 and Ser771. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6292–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snabaitis AK, Cuello F, Avkiran M. Protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylates and inhibits the cardiac Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. Circ Res. 2008;103:881–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fliegel L, Walsh MP, Singh D, Wong C, Barr A. Phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of the Na+/H+ exchanger by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 1992;282:139–145. doi: 10.1042/bj2820139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komukai K, Pascarel C, Orchard CH. Compensatory role of CaMKII on ICa and SR function during acidosis in rat ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:353–61. doi: 10.1007/s004240100549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomura N, Satoh H, Terada H, Matsunaga M, Watanabe H, Hayashi H. CaMKII-dependent reactivation of SR Ca2+ uptake and contractile recovery during intracellular acidosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H193–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00026.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Said M, Vittone L, Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Ferrero P, Kranias EG, Mattiazzi A. Role of dual-site phospholamban phosphorylation in the stunned heart: insights from phospholamban site-specific mutants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1198–H1205. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00209.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeSantiago J, Maier LS, Bers DM. Phospholamban is required for CaMKII-dependent recovery of Ca transients and SR Ca reuptake during acidosis in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Ferrero P, Said M, Vittone L, Kranias EG, Mattiazzi A. Role of phosphorylation of Thr17 residue of phospholamban in mechanical recovery during hypercapnic acidosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:114–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valverde CA, Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Reyes M, Kranias EG, Escobar AL, Mattiazzi A. Phospholamban phosphorylation sites enhance the recovery of intracellular Ca2+ after perfusion arrest in isolated, perfused mouse heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sag CM, Dybkova N, Neef S, Maier LS. Effects on recovery during acidosis in cardiac myocytes overexpressing CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Prigent K, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Feuvray D. Modulation by pH0 and intracellular Ca2+ of Na+/H+ exchange in diabetic rat isolated ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1997;80:253–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moor AN, Murtazina R, Fliegel L. Calcium and osmotic regulation of the Na+/H+ exchanger in neonatal ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:925–36. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Jr, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:409–17. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vila-Petroff MG, Aiello EA, Palomeque J, Salas MA, Mattiazzi A. Subcellular mechanisms of the positive inotropic effect of angiotensin II in cat myocardium. J Physiol. 2000;529:189–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cingolani HE, Mattiazzi AR, Blesa ES, Gonzalez NC. Contractility in isolated mammalian heart muscle after acid-base changes. Circ Res. 1970;26:269–78. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez NG, Alvarez BV, Camilión de Hurtado MC, Cingolani HE. pHi regulation in myocardium of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Compensated enhanced activity of the Na+-H+ exchanger. Circ Res. 1995;77:1192–1200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edelman AM, Blumenthal DK, Krebs EG. Protein serine/threonine kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:567–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakabayashi S, Bertrand B, Ikeda T, Pouysségur J, Shigekawa M. Mutation of calmodulin-binding site renders the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE1) highly H+-sensitive and Ca2+regulation-defective. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13710–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertrand B, Wakabayashi S, Ikeda T, Pouysségur J, Shigekawa M. The Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 (NHE1) is a novel member of the calmodulin-binding proteins. Identification and characterization of calmodulin-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13703–09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White RR, Kwon YG, Taing M, Lawrence DS, Edelman AM. Definition of optimal substrate recognition motifs of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases IV and II reveals shared and distinctive features. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3166–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karmazyn M. The sodium-hydrogen exchange system in the heart: its role in ischemic and reperfusion injury and therapeutic implications. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12:1074–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila-Petroff M, Salas MA, Said M, Valverde CA, Sapia L, Portiansky E, Hajjar RJ, Kranias EG, Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Mattiazzi A. CaMKII inhibition protects against necrosis and apoptosis in irreversible ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:689–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura TY, Iwata Y, Arai Y, Komamura K, Wakabayashi S. Activation of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 is sufficient to generate Ca2+ signals that induce cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Res. 2008;103:891–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoch B, Meyer R, Hetzer R, Krause EG, Karczewski P. Identification and expression of d-isoforms of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ Res. 1999;84:713–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97:1314–22. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.