Approximately 4 million patients receive treatment annually in intensive care units (ICU) in the United States (1) with ~10% requiring >3 days of mechanical ventilation and extended ICU stays. These patients, labeled as “chronically critically ill” (CCI), although small in number, consume 25–40% of ICU resources with resulting high in-hospital mortality (40%) and post-discharge morbidity (2). While in-hospital outcomes are poor, research has also shown that this population is at risk for high mortality and morbidity during the immediate post-discharge phase (3, 4). Unlike their short-stay ICU counterparts, CCI patients are at high risk for readmission, complications, and death after hospital discharge. As a result, they require continued support from family and/or professional caregivers after hospital discharge, regardless of discharge location (5).

Many studies on informal caregivers have focused upon caregivers of infirm elderly (6), Alzheimer’s disease (7), cancer (8), stroke (9), and heart failure (10). The characteristics of the caregivers of these patients as well as the risks for caregiver depression have remained relatively consistent across these disease groups. These characteristics include: female gender, relative of the care receiver, being employed, and being younger in age (11, 12).

More recently, studies (13–16) have examined the characteristics and outcomes of caregiving in caregivers of CCI patients. Their characteristics are similar to the characteristics of other caregiver groups in that they are younger in age, predominantly female and are spouses of the care receiver. Outcomes, while not studied as extensively with CCI caregivers as with other caregiver groups, have shown varying degrees of depressive symptomatology with rates of depression consistent with (and at times greater than) rates associated with such caregiver groups as Alzheimer’s, cancer, and stroke. (14, 16).

Despite documentation of depression among CCI caregivers, little research has explored subgroups based upon race. In the non-CCI caregiver literature, multiple studies have examined the impact of racial differences on caregiver stressors and outcomes (17–20), yet no such work has been done with the caregivers of CCI patients. Therefore, the purposes of our study were to describe clinical and demographic characteristics for caregivers and to examine the role of race, as well as other clinical and demographic variables, as predictors of depressive symptomatology 2 months post-hospital discharge for caregivers of CCI patients.

Materials and Methods

The parent study was a quasi-experimental trial of an in-hospital intervention focused upon a structured format for communication with families of CCI patients during their ICU stay. Chronically critically ill was defined as continuous mechanical ventilation beyond 72 hours while in the ICU. While the focus of the present study was on outcomes after hospital discharge, the eligibility criterion of >72 hours of continuous mechanical ventilation while in the ICU was established while the patient was still in the hospital. We chose 72 hours in order to exclude patients who were simply slow to wean from ventilation while still capturing those whose clinical problems were likely to entail a high risk of continued mortality and morbidity.

Eligibility criteria for patients were: (a) ≥ 72 hours of continuous mechanical ventilation with no expectation by the attending physician of extubation or discharge from the ICU within the next 48 hours; (b) lacking decisional capacity as indicated by a Glasgow Coma Scale < 6 and confirmed by the ICU attending physician; (c) no home mechanical ventilation prior to this hospital admission; and (d) an identified family surrogate decision maker/caregiver present.

Family surrogates/caregivers were eligible if they were: (a) identified as the appointed surrogate through having power of attorney or were the next of kin and (b) were available for participation in on-site family meetings. In the case of multiple family members, the decision maker was defined as the person from whom consent was being obtained for medical interventions.

Subjects were enrolled from five intensive care units (ICUs) at two academic medical centers. The ICUs included a surgical, medical, and neuroscience ICU at a university-affiliated, private not-for-profit tertiary care medical center, and a medical and surgical ICU at a university-affiliated county hospital in the same city. IRB approval was obtained from both institutions before beginning the study.

Between September, 2005 and February 2008, research nurses screened all patients admitted to all ICUs at the study sites to determine patient eligibility. Once patients were deemed eligible, the caregivers were approached for written informed consent. Baseline data were obtained at the time of study enrollment for patients (clinical and demographic information) and caregivers (demographic information). For the portion of the study that pertains to this presentation, research nurses tracked patients until hospital discharge and then contacted caregivers of discharged patients 2 months post-hospital discharge. The first caregiver interview was conducted in person at the time of study enrollment and the second interview was conducted 2 months post-hospital discharge via telephone. The purpose of the interviews was to obtain demographic and clinical information and to assess the caregiver’s depression and physical health status.

Prior to data collection, research nurses were trained in the use and administration of all interview tools. Inter-rater reliabilities between the research nurses was assessed; acceptable reliabilities of 80% agreement, as well as Pearson correlations of at least .80 (for continuous variables) and a kappa statistic of .70 (for categorical variables) were established before data collection proceeded (21, 22). Every four months throughout the data collection period, ongoing inter-rater reliability was assessed and retraining occurred if reliabilities fell below acceptable levels.

Instruments

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D) was used to measure symptoms of caregiver depression. The CES-D focuses on distress symptoms prevalent among nonpsychiatric populations and is a measure of depressed mood. The CES-D has been used with samples of caregivers of patients receiving long-term mechanical ventilation (14, 16). It is a 20-item tool that uses a 4-point Likert-type summative scale. Scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating more depressed mood. A score of >15 has been identified as indicating depressive symptoms with established cut-off levels defined as mild depression (CES-D score 16–20), moderate (CES-D score 21–26) and severe (CES-D score 27–60) (9). Reliability and validity of the tool have been established (23). For the present study, Cronbach alphas’ ranged from .89 – .93.

Caregiver health related quality of life (HRQOL) was measured using a single-item measure. A single-item measure was chosen to minimize subject burden with the use of multiple item health status instruments. Single-item measures of HRQOL (24, 25) have demonstrated good psychometric properties (24, 25). Our single item measure used the same 5 point Likert scale as others (24, 25) with scores ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

The Charlson Weighted Index of Co-morbidity was used to assess patient comorbidity within the four weeks prior to the index hospitalization. The tool is a weighted index that takes into account the number and seriousness of 19 medical conditions that are weighted on a scale from 1–6 (higher weights indicate a more serious comorbidity). Total scores range from 0–37. The tool is widely used with established reliability and validity reported (26).

Caregiver demographic variables were obtained through a study enrollment interview. Race of the caregiver was self-identified. For the purposes of the study, Caucasian caregivers were those who identified themselves as Caucasian. Non-Caucasian caregivers were those who identified themselves as African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, or “other non-Caucasian”.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between Caucasian and non-Caucasians were done using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for non-skewed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U test for skewed continuous variables, and χ2 for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression was used to examine a model for predicting depressive symptomatology post-hospital discharge. Sample size for the present analyses was calculated using power analysis that incorporated the following assumptions: α = .05, non-directional hypotheses, medium effect size (R2=.10), and a desired power of .80. Based on these assumptions, a sample size of 143 was needed for multiple regression analysis to examine predictor variables for caregiver depression.

Results

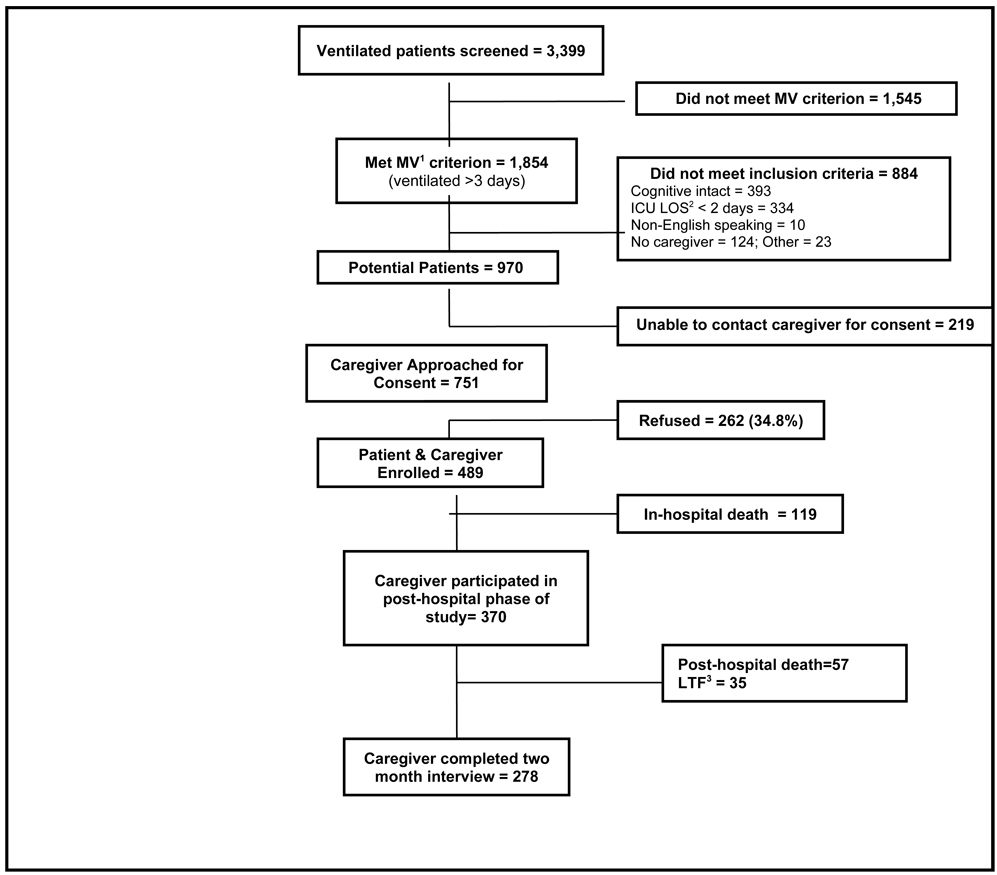

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the total sample, the percentage of eligible patients, eligible caregivers, refusals, and in-hospital deaths. The 31.7% caregiver refusal rate is consistent with that found in previous work with this population (16) and was most often related to the caregiver feeling “overwhelmed.” A total of 370 caregivers were enrolled for the post-hospital discharge portion of the study with 278 caregivers completing the entire 2-month post-discharge interview.

Figure 1.

Caregiver sample selection

1MV, mechanical ventilation

2ICU LOS, Intensive care unit length of stay

3LTF, lost to followup

Caregiver Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes caregiver demographic characteristics for Caucasian and non-Caucasian caregivers. A majority of the non-Caucasian caregivers were African American (n=97); 12 were Hispanic, 5 Asian, and 4 “other non-Caucasian” but not identified. In general, caregivers were predominantly female, Caucasian, middle-aged, employed, and a relative of the patient (such as a spouse or child). In addition, over half of the caregivers had been living with the patient prior to this hospitalization but only 24.9% (n=89) served as a caregiver to the patient prior to this hospitalization.

Table 1.

Comparison of caregiver demographic variables by race (n=370).

| Variable | Non-Caucasian (n=118) |

Caucasian (n=252) |

t | p | d2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)1 | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age of caregiver (years) | 49.4 (14.5) | 54.3 (14.3) | 3.05 | .002 | .34 |

| Confidence Interval | 46.3 – 51.7 | 52.7 – 56.2 | |||

| Health status, caregiver | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.9) | 0.81 | .42 | .09 |

| Confidence Interval | 3.3 – 3.6 | 3.4 – 3.6 | |||

| CES-D score | 23.4 (11.2) | 23.7 (10.9) | 0.19 | .85 | .02 |

| Confidence Interval | 21.3 – 25.4 | 22.3 – 25.1 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | p | Φ3 | |

| Female gender | 92 (78.0) | 167 (67.0) | 0.61 | .43 | .04 |

| Married | 65 (57.5) | 190 (77.2) | 14.62 | .001 | .20 |

| Relationship to patient | 18.93 | .001 | .23 | ||

| • Spouse | 29 (24.6) | 112 (44.4) | |||

| • Son/daughter | 41 (34.7) | 58 (23.0) | |||

| • Sibling | 14 (11.9) | 21 ( 8.3) | |||

| • Parent | 32 (27.1) | 47 (18.7) | |||

| • Other | 2 ( 1.7) | 14 ( 5.6) | |||

| Variable | Non-Caucasian (n=118) |

Caucasian (n=252) |

χ2 | p | Φ |

| n (%) | n (% ) | ||||

| Current employment | 0.04 | .84 | .01 | ||

| • Employed | 70 (59.8) | 148 (58.7) | |||

| Education4 | 2.99 | .23 | .09 | ||

| • <HS graduate | 7 ( 6.1) | 21 ( 8.4) | |||

| • >= HS graduate, <college | 87 (75.6) | 166 (65.9) | |||

| • >=College graduate | 21 (18.2) | 62 (24.7) | |||

| Income ($/year)5 | 18.75 | .001 | .23 | ||

| • < $20,000 | 38 (34.5) | 37 (16.4) | |||

| • $21,000 – $49,000 | 45 (40.9) | 92 (40.9) | |||

| • >$50,000 | 27 (25.5) | 96 (42.7) | |||

| Prior caregiver: Yes | 36 (30.8) | 57 (22.8) | 2.68 | .10 | .09 |

| Co-residence with patient: Yes | 59 (50.0) | 150 (59.5) | 2.83 | .09 | .09 |

| Moderate-Severe Depressive Symptomatology During Patient ICU Stay |

67 (60.4) | 138 (54.8) | 1.23 | .75 | .06 |

| Taking medication for mood: Yes6, 7 | 6 ( 5.6) | 37 (15.5) | 6.68 | .01 | .14 |

SD, Standard deviation

d, Cohen’s d (effect size)

Phi coefficient (effect size)

Three missing cases for this variable in the Non-Caucasian group (n=115).

Due to missing cases, sample sizes are: Non-Caucasian (n=110) and Caucasian (n=225).

Due to missing cases, sample sizes are: Non-Caucasian (n=107) and Caucasian (n=238).

OR (Odds Ratio): 3.10, CI (95% Confidence Interval): 1.27, 7.59, p=.01.

Comparisons between Caucasian and non-Caucasian caregivers

There was a statistically significant difference between Caucasian and non-Caucasian caregivers on a variety of demographic characteristics. Non-Caucasian caregivers were younger, less likely to be a spouse and more likely to be the child or parent of the patient, less likely to be married, and more likely to have a lower annual household income than Caucasian caregivers. For both groups, at the time of the patient’s ICU admission, over half of the caregivers had CES-D scores that classified them as having moderately-severedepressive symptomatology. There was no statistically difference by race (p= .85).

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes

Patient characteristics (n = 370) are presented in Table 2. The median hospital length of stay was 22 days (range 6 – 121), the median ICU stay was 15 days (range 4 – 107) with the median length of mechanical ventilation being 11 days (range 4 – 107). In general, patients had few comorbidities prior to this hospitalization. Ninety per cent of patients (n = 332) who survived hospitalization were discharged to a institutional setting. Over half (57.2%) of all patients were discharged with a tracheotomy in place. During the 2-month post-hospital discharge period, 57 patients (15.4%) who were alive at hospital discharge died and 35 (9.4%) caregivers dropped out or were unavailable for follow-up. Patients who were initially discharged to home had a significantly lower rate of post-hospital mortality (2.9%) than did those who were discharged to an institution (54.7%) (OR: 8.61; 95% CI, 1.16 to 63.94, p=.01). Patients discharged to a nursing home had the highest rate of post-hospital mortality (24.1%), followed by those discharged to an LTAC (23.7%), and those discharged to a rehabilitation facility (3.1%).

Table 2.

Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Variables Between Chronically Critically Ill Patients of Caucasian and Non-Caucasian Caregivers at Hospital Discharge (n=370).

| Variable | Non-Caucasian Caregivers (n=118) |

Caucasian Caregivers (n=252) |

t | p | d2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)3 | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age (years) | 51.9 (16.8) | 56.9 (17.4) | 2.60 | .008 | .30 |

| Confidence Interval | 48.8 – 54.9 | 54.8 – 59.1 | |||

| Charlson score1 | 1.4 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.7) | −0.05 | .96 | .02 |

| Confidence Interval | 1.0 – 1.8 | 1.1 – 1.6 | |||

| Hospital stay (days)1 | 25.1 (17.2) | 27.2 (15.3) | −1.99 | .05 | .13 |

| Confidence Interval | 21.9–28.2 | 25.3– 29.1 | |||

| ICU stay (days)1 | 15.2 (12.6) | 14.9 (9.9) | −0.37 | .71 | .02 |

| Confidence Interval | 12.9 – 17.5 | 13.7 – 16.2 | |||

| Mechanical ventilation (days)1 | 11.9 (12.5) | 9.9 (7.9) | −1.12 | .26 | .21 |

| Confidence Interval | 9.7 – 14.2 | 8.9 – 10.9 | |||

| Variable | Non-Caucasian1 Caregivers (n=118) |

Caucasian Caregivers (n=252) |

χ2 | p | Φ5 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Female gender | 55 (46.6) | 108 (42.9) | 0.46 | .50 | .04 |

| Primary Diagnosis | 2.51 | .64 | .08 | ||

| • Cardiac | 9 ( 7.6) | 27 (10.7) | |||

| • Trauma | 35 (29.7) | 70 (27.8) | |||

| • Respiratory | 26 (22.0) | 47 (18.7) | |||

| • Neurologic | 27 (22.9) | 51 (20.2) | |||

| • Other4 | 21 (17.8) | 57 (22.6) | |||

| Discharged from hospital | 0.01 | .91 | .00 | ||

| • With tracheotomy | 67 (56.8) | 143 (57.4) | |||

| Discharged from hospital | 0.98 | .61 | .05 | ||

| • With ventilator | 30 (25.4) | 53 (21.3) | |||

| Discharge disposition | 5.75 | .22 | .13 | ||

| • LTAC | 53 (44.9) | 103 (40.9) | |||

| • Rehabilitation | 23 (19.5) | 54 (21.4) | |||

| • Nursing Home | 25 (21.2) | 62 (24.6) | |||

| • Home | 16 (13.6) | 22 ( 8.7) | |||

| • Other | 1 ( 0.8) | 11 ( 4.4) | |||

| Post-hospital discharge death | 18 (16.7) | 39 (16.6) | 0.00 | .99 | .00 |

These variables were positively skewed. Mann-Whitney U was performed and z values and their associated p-values are reported.

d, Cohen’s d (effect size)

SD, Standard deviation

Other includes the following diagnoses: Gastrointestinal (n=34), metabolic (n=3), hematologic (n=1), infectious disease (n=33), and other (n=7).

Phi coefficient (effect size)

Outcomes and Experiences of Caregiving

Depression

Upon entry into the study (ICU enrollment), 75.5% of the sample (n=265) had CES-D scores >15 and were at risk for depression with 19.1% classified as having moderate and 39% as severe depressive symptomatology. Two months post-discharge, 43.3% (n=120) had CES-D scores >15 with 10.5% classified as moderate and 20.2% classified as severe depressive symptomatology. There were no differences between classifications of depressive symptomatology by race at enrollment (p=.75) or 2 months post-hospital discharge (p=.46). Almost one-half (40.4%) of caregivers classified as having moderate-severe depressive symptomatology at ICU enrollment were still classified as such 2 months post-hospital discharge (OR: 3.13, 95% CI: 1.77, 5.53, p=.001). This significant relationship held for both Caucasian (p=.001) and non-Caucasian (p=.009) caregivers.

Next, we examined whether overall CES-D scores 2 months post-hospital discharge varied according to caregiver race. There were no statistically significant differences in CES-D scores by race (p=.14). We also examined whether or not the changes in depression over time (enrollment into study and 2 months post-hospital discharge) were different by race. A Repeated Measures ANOVA (RMANOVA) was conducted and while the overall decrease in CES-D scores over time was statistically significant (F=78.25, p=.001, η2=.781), there was no significant difference in the change over time by race (F=0.61, p=.44).

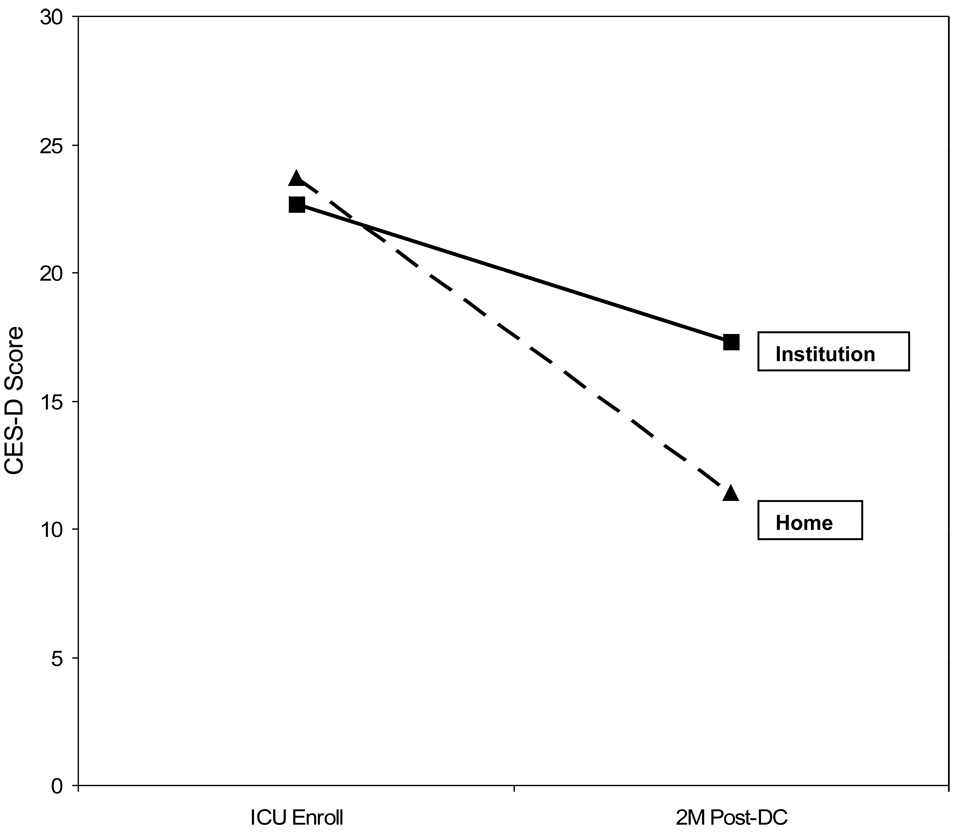

We then examined whether there were differences in CES-D scores by patient discharge disposition. Prior research had shown that caregivers of patients discharged to an institutional setting had significantly higher CES-D scores and poorer health outcomes than caregivers of patients discharged to home (16) but this finding had not been replicated (14). As seen in Figure 2,CES-D scores of caregivers of patients residing in an institutional setting 2 months post-hospital discharge were higher (mean=17.32; SD=12.75; 95% CI: 15.11, 19.68) than for the caregivers of patients residing at home (mean=11.00; SD=11.48; 95% CI: 8.83, 13.17) with caregivers of patients residing in an institutional setting having significantly higher odds of depressive symptomatology than caregivers of patients residing at home (OR: 2.75; 95% CI: 1.61, 4.67; p=.001). Finally, we found that 38.3% of caregivers of patients residing in an institutional setting were classified as having moderate-severe depressive symptomatology as compared to 17.2% of caregivers of patients residing at home (χ2=13.5, p=.001).

Figure 2.

Change in CES-D Over Time by Patient Location at 2 Months Post-Discharge (n=278)

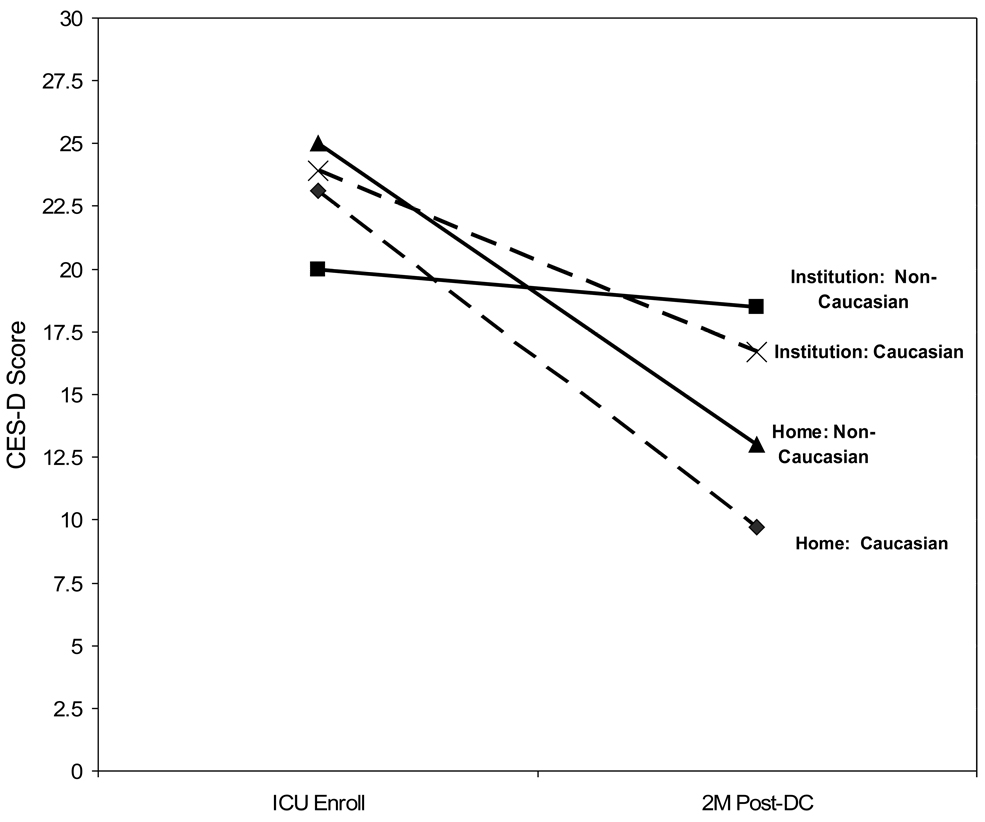

Using factorial ANOVA, we examined the main effects of location and race as well as the interaction effects upon the outcome of change in CES-D scores from study enrollment to 2 months post-discharge. The interaction effect was not significant (p=.31); however the main effects of patient location (p=.001) and race (p=.027) were significant. As seen in Figure 3, non-Caucasian caregivers of patients in an institutional setting had the least improvement in CES-D scores (mean change = 1.49) over time followed by Caucasian caregivers of institutionalized patients (mean change = 7.20). Non-Caucasian caregivers of patients residing at home had an average improvement of CES-D scores of 11.3 while Caucasian caregivers of patients residing at home had the greatest improvement in scores (mean change 13.35). Using Scheffe’s post-hoc tests to examine differences between the four groups, we found one significant group comparison; Caucasian caregivers of patients residing at home had a greater improvement in CES-D scores over time when compared to non-Caucasian caregivers of patients residing in an institutional setting (mean difference=.43, CI: .03, .83, p=.006).

Figure 3.

Change in CES-D Over Time by Patient Location at 2 Months Post-Discharge for Non-Caucasian (n=84) and Caucasian Caregivers (n=193)

Caregiver Depression and Patient Readmission

Prior research has documented an association between caregiver depression and patient readmission (10) for patients with heart failure. Given the documented risk of readmission for CCI patients, we wanted to explore the relationship between CES-D scores and readmission for this population. The overall relationship between caregiver CES-D scores 2 months post-hospital discharge and patient readmission within 2 months post-hospital discharge was statistically significant, r(298) = .16, 95% CI: .05, .26, p=.007. However, when the nature of this relationship was examined by race and patient residence (home vs. institution), the significant relationship between caregiver depression and patient readmission held for only one group: patients residing at home with caregivers of Caucasian race (r (84) = .27, p=.013).

Medication Use for Mood

Upon study enrollment, 12.8% of all caregivers (n=42) were taking medication for their mood with Caucasians being 3 times more likely to be taking medications than their non-Caucasian counterparts (p=.01). This difference did not hold, however, two months post-hospital discharge.

Physical Health Status

Using RMANOVA, we found no statistically significant difference in health status over time by race (p=.25), but did find a statistically significant decrease in the overall health status of all caregivers over time (F(1,288) = 23.5, p=.001).

Change in employment

Two months post-hospital discharge, 48.2% (n=105) of caregivers who had been employed at the time of study enrollment, either reduced their work hours, quit or were fired as a result of assuming the caregiving role. There was no difference in change in employment by race (p=.50) nor was there a significant relationship between CES-D scores and employment status (p= .96).

Predictors of post-hospital depression

Multiple linear regression was used to examine the relationship of specific predictor variables (shown to relate to caregiver depression in CCI as well as other patient populations) to caregiver depression 2 months post-hospital discharge. The 6 predictor variables were regressed on the criterion variable (CES-D scores 2 months post-hospital discharge). Using baseline CES-D as a covariate, we then entered the next four variables, and as the last step in the model, added caregiver race to see if there was a change in the model based uponrace. With all variables in the model, the adjusted R2 was 0.227 (p=.001). As seen in Table, 3, covarying the effect of baseline CES-D scores, the following variables made statistically significant unique contributions with all variables in the model: caregiver gender, caregiver health status at hospital discharge, and location of the patient 2 months post-hospital discharge. The addition of caregiver race made a minimal and non-significant contribution (R2 change = .01, p=.09).

Table 3.

Standardized estimated from ordinary least-squares regression of caregiver depression on caregiver and care-receiver variables (n = 237).

| Variables | B1 | SE B2 | 95% CI3 | β4 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | |||||

| CES-D @ enrollment5 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.21, 0.50 | .30 | .001 |

| Age (years) | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.18, 0.04 | − .07 | .235 |

| Gender (1=female, 2=male) |

−4.18 | 1.77 | −7.67, −0.70 | −.14 | .019 |

| Health status @ enrollment6 | −2.26 | 0.86 | −3.96, −0.57 | −.17 | .009 |

| Ethnicity (0=Non-Caucasian, 1=Caucasian) |

−2.77 | 1.60 | −5.93, 0.39 | −.10 | .085 |

| Care-receiver (patient) | |||||

| Living location 2 | −6.68 | 1.44 | −9.51, −3.84 | −.27 | .001 |

| Months post-discharge (1=institution; 2=home) |

R2 (adj) = .227, F(6,231)=12.60, p=.001.

Unstandardized b coefficient.

SE B, Standard error of b (unstandardized)

CI, Confidence interval

β, Standardized regression coefficient (beta)

Higher numbers indicate more depressive symptomatology.

Higher numbers indicate better physical health status.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the impact of ethnicity upon characteristics and outcomes for caregivers of CCI patients. CCI caregivers shared many of the same differences between Caucasian and non-Caucasian caregivers as has been reported with other caregiver groups (18, 20, 17). In addition, by utilizing a framework that included both individual and situational variables, we were able to better understand the relationships among such factors as race, institutional setting, and depressive symptomatology for this caregiver population (30). Some specific findings are worth noting. First, given our findings of increased depressive symptomatology in caregivers of patients discharged to an institutional setting, healthcare providers, as well as family, should be aware of the risk for ongoing depressive symptomatology during the post-discharge trajectory of care for CCI patients.

Second, our reported rate of depressive symptomatology is higher than reported for many other caregiver groups and is higher than reported for caregivers of survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation (14–16). This is a population “at risk” for depression and that needs to identified early in order to facilitate treatment when necessary. Third, given the low use of medication for mood among non-Caucasian caregivers, this subgroup of CCI caregivers may be at additional risk for untreated depressive symptomatology.

Finally, our finding of incidence of work reduction for the caregivers of CCI patients is higher than reported for other caregiver groups (15, 28) and has significant financial implications for individuals as well as society. Interventions to provide education and support for these caregivers need to address issues relevant to work since such a large percentage of CCI caregivers are young and employed.

Areas for future research need to include clarification of the underlying causes for differential medication use by race (27) and to more fully describe the characteristics of those most at risk for ongoing depressive symptomatology. In addition, research should focus upon the reasons for employment changes as well as an examination of the use of such strategies as social support networks (shown to minimize depressive symptomatology in other caregiver populations) and the impact upon not only depressive symptomatology but upon employment as well. Such information is needed in order to provide effective interventions for this newly identified, vulnerable population.

There are several limitations to the study. First, our attrition rate was high (24.9%), thus limiting generalizability of results. A second limitation is the high false-negative rate (36.4 to 40%) previously reported for the CES-D scale (29) which, most likely, has led to us having underreported the number of caregivers whoexperienced depressive symptomatology. Finally, the use of a single item indicator for HRQOL, while not a focus of this study, has as a limitation, reduced ability to provide information and insight into HRQOL for these caregivers.

Conclusions

Caregivers of CCI patients continue to remain an unrecognized group in the health care system, despite the fact that they exhibit many of the same characteristics and outcomes as caregivers of other recognized groups and report higher rates of depression. Like other caregivers, the impact of race upon assessment and treatment of depression for caregivers of CCI patients is complex and requires further research. Design and testing of interventions that are aimed at reducing depression through early identification of these “at risk” individuals with loved ones in various discharge locations is needed. Such work is vital if we are to meet the mental health needs of this growing population of caregivers.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research, Grant No. RO1-NR0-08941.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The work was performed at Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals of Cleveland, and MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, OH.

Contributor Information

Sara L. Douglas, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University.

Barabara J. Daly, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University.

Elizabeth O’Toole, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University.

Ronald L. Hickman, Jr., Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- 1.Davydow D, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson SS, Bach PB. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson SS, Bach PB, Brzozowski L, et al. Outcomes after long-term acute care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1568–1573. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9809002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Gordon N, et al. Survival and quality of life: short-term versus long-term ventilator patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2655–2662. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox CE, Carson SS, Hoff-Linquist JA, et al. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R9. doi: 10.1186/cc5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennstedt S, Cafferata GL, Sullivan L. Depression among caregivers of impaired elders. J Aging Health. 1992;4:58–76. doi: 10.1177/089826439200400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, et al. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:1105–1117. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bay E, Donders J. Risk factors for depressive symptoms after mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2008;22:233–241. doi: 10.1080/02699050801953073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders MM. Factors associated with caregiver burden in heart failure family caregivers. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30:943–959. doi: 10.1177/0193945908319990. PMID: 18612092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covinskky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller B, Townsend A, Carpenter E, et al. Social support and caregiver distress: a replication analysis. J Geontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:S249–S256. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas SL, Daly BJ. Caregivers of long-term ventilator patients: physical and psychological outcomes. Chest. 2003;123:1073–1081. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Im KA, Belle SH, Schulz R, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of caregiving after prolonged (≥ 48 hours) mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest. 2004;125:597–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Quin L, et al. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, et al. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128:3925–3936. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45:90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research. Gerontologist. 2002;42:237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: a sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siefert ML, Williams A, Dowd MF, et al. The caregiving experience in a racially diverse sample of cancer family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305760.04357.96. PMID: 18772665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bland J, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1988;8:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis J, Koch L. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ensel WM. Measuring depression: The CES-D scale. In: Lin N, Dean A, Ensel W, editors. Social Support, Life Events, and Depression. Academic Press: New York, NY; 1986. pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunny KA, Perri M. Single-item versus multiple-item measures of health related quality of life. Psychol Rep. 1991;69:127–130. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crane HM, Van Rompaey SE, Dillingham PW, et al. A single-item measure of health-related quality of life for HIV-infected patients in routine clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:161–174. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sleath B, Tulsky JA, Peck BM, et al. Provider-patient communication about antidepressants among veterans with mental health conditions. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, et al. The influence of caregiver mastery on depressive symptoms. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers JK, Weissman MM. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1081–1083. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raveis VH, Karus DG, Siegel K. Correlated of depressive symptomatology among adult daughter caregivers of a parent with cancer. Cancer. 1998;83:1652–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]