Abstract

Meiosis is the process which produces haploid gametes from diploid precursor cells. This reduction of chromosome number is achieved by two successive divisions. Whereas homologs segregate during meiosis I, sister chromatids segregate during meiosis II. To identify novel proteins required for proper segregation of chromosomes during meiosis, we applied a high-throughput knockout technique to delete 87 S. pombe genes whose expression is upregulated during meiosis and analyzed the mutant phenotypes. Using this approach, we identified a new protein, Dil1, which is required to prevent meiosis I homolog non-disjunction. We show that Dil1 acts in the dynein pathway to promote oscillatory nuclear movement during meiosis.

Keywords: fission yeast, meiosis, chromosome segregation, dynein, nuclear movement

Introduction

The reduction of chromosome number during meiosis is achieved by a single round of DNA replication followed by two rounds of chromosome segregation, called meiosis I and meiosis II. While the second meiotic division is similar to mitosis in that sister centromeres segregate to opposite poles, the first meiotic division is fundamentally different and ensures segregation of homologous centromeres. Paliulis and Nicklas demonstrated that chromosome segregation during meiosis is determined by special properties of the meiotic chromosomes rather than by spindle components or other cytosolic factors.1 There are three major features of meiotic chromosomes and their associated proteins responsible for their unique meiosis I segregation.2-4 The first is recombination in which homologous chromosomes cross over to form chiasmata and to designate bivalents for disjunction. The second meiosis-specific feature is mono-orientation of sister kinetochores. The third meiosis-specific feature is the protection of centromeric cohesion. Disturbing any of these processes may lead to missegregation of chromosomes and aneuploidy, which is the major cause of miscarriages and mental retardation in humans.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is an excellent model organism for the study of chromosome segregation, as it is amenable to both genetic and cell biology techniques. Moreover, fission yeast chromosomes have large complex centromere structure, similar to those of higher eukaryotes.5 We have been studying the consequences on meiotic chromosome segregation of deleting S. pombe genes whose mRNAs were upregulated during meiosis, arguing that meiotic regulators governing the aforementioned processes would be preferentially expressed during meiosis. We previously deleted 180 genes and identified new regulators of meiotic chromosome segregation, including the protector of centromeric cohesion Sgo1 and a new protein required for the initiation of meiotic recombination Mde2.6,7 Martin-Castellanos et al. used a similar approach to delete 160 genes and identified seven novel genes required for critical meiotic events.8 Here we report deletion and phenotypical characterization of additional 87 meiotically upregulated genes.

Results

A screen for genes required for meiotic chromosome segregation

We have designed a high-throughput strategy to knock-out genes in the fission yeast S. pombe on a large scale.6,9 In addition to its high knockout efficiency, our strategy has the advantage that a library of knockout plasmids is created. The plasmids are freely available and can be used to knockout genes in strains with various genetic backgrounds. Here we applied this technique to delete selected meiotically upregulated genes.10 We were able to delete 87 genes out of 92 selected (Table S1). The genes which resisted deletion may be essential genes or genes refractory to homologous recombination.11 Two of these genes have been shown to be essential for cell growth during the course of this work.8,12

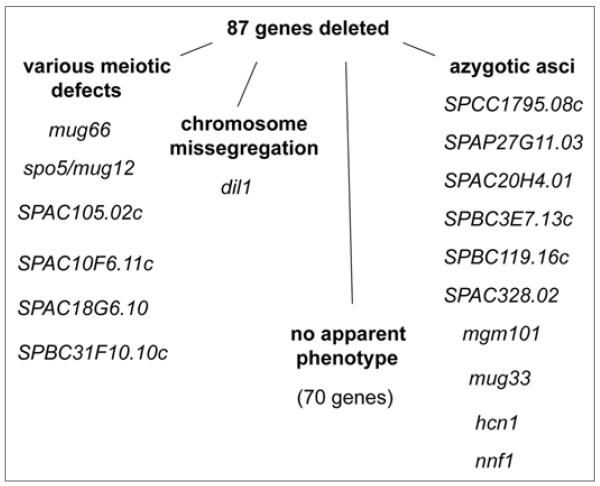

In order to analyze chromosome segregation, we knocked-out the genes in a haploid homothallic h90 strain where chromosome I was marked with GFP (lys1-GFP).13 In this strain, GFP tagged LacI molecules bind to lacO repeats inserted within the lys1 locus located near the centromere. This strain generates cells of both mating types and undergoes mating and meiosis on sporulation medium. We sporulated mutant cells, stained nuclei with Hoechst dye and scored segregation of lys1-GFP dots in asci. 70 mutants had no apparent phenotype and faithfully segregated their chromosomes. Ten mutants formed azygotic asci, which may indicate that the deletion caused defects in mitotic growth, as we have previously observed (Fig. 1).6 Consistent with this hypothesis, hcn1+ and nnf1+ genes have been shown to be required for normal mitotic growth.14,15 One mutant (SPAC458.04c) missegregated chromosomes during meiosis and six other mutants displayed various meiotic defects such as fragmented nuclei and abnormal number of spores (Fig. 1). Abnormal spore morphology in spo5/mug12 and mug66 mutants have been previously described.8,16

Figure 1.

Summary of the screen. Chromosome segregation in deletion mutants generated by a large-scale knockout approach was analyzed by scoring lys1-GFP in meiotic cells. The genes were sorted into four categories according to their phenotype. See Table S1 for the full list of analyzed genes.

Dil1 is required for proper segregation of homologs during meiosis I

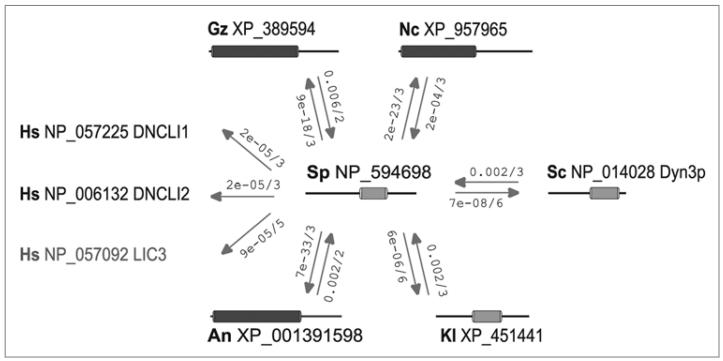

We further analyzed the SPAC458.04cΔ mutant that missegregated chromosomes during meiosis. The open reading frame of SPAC458.04c is predicted to encode a 38 kDa protein with no obvious orthologs in other organisms.17 In the current S. pombe genome database17 SPAC458.04c is listed as an orphan sequence with no known sequence domains and a distinctive upregulation during the meiotic cell cycle and in stressed cells.10,18 We performed a more detailed computational analysis of SPAC458.04c which revealed a similarity to dynein light intermediate chain proteins (DLIC) (Figs. 2 and S1 and http://mendel.imp.ac.at/SEQUENCES/DLIC/). Members of the DLIC family are associated with cytoplasmic dynein which plays a central role in chromosome segregation during both mitosis and meiosis.19-23 Structural and sequence similarity analyses suggest that DLIC proteins are closely related to the structural family of G proteins, and might adopt a P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases-like fold (see the Materials and Methods and http://mendel.imp.ac.at/SEQUENCES/DLIC/). Given the similarity between the SPAC458.04c and DLIC proteins, we decided to call SPAC458.04c gene dil1 (dynein intermediate light chain—like 1). Sequence alignments suggested that the N-terminus of the Dil1 may be longer than predicted (see Materials and Methods and Fig. S1). Consistent with this notion, our mass-spectrometry analysis of TAP-tagged Dil1 purified from cycling cells identified N-terminally acetylated peptide (MDELLEK) mapping to this region.

Figure 2.

Dil1/SPAC458.04c shares similarity with dynein light intermediate chain proteins (DLIC). Schematic representation of bidirectional best PSI-BLAST similarities which were used to establish the homology of SPAC458.04c to fungal DLIC family members. The query database used is the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database (Dec 2007) supplemented by the Schizosaccharomyces octosporus SPAC458.04c sequence.48 Directed arrows mark significant PSI-BLAST links, with E-value and iteration round of the hit indicated alongside. Protein sequences are listed using a 2 letter species code followed by the NCBI accession number. Protein domain architecture corresponding to the concise result view of NCBI-CD-search is indicated for each protein. Dark grey boxes indicate DLIC/PF05783.2 domain hits found with highly significant E-values (E < 1e-20) in fungal proteins which are known members of the DLIC family and are reciprocal best DNCLI1/2 proteome hits (more distant LIC3 shown in grey). Light grey boxes indicate borderline DLIC/PF05783.2 domain similarity with E-values between 0.005 and 0.10. Links of SPAC458.04c to non-fungal DLIC family members are exemplified for human. The observed transitive reciprocal best links from S. pombe over fungal DLIC to non-fungal DLIC are not shown. Species code: An Aspergillus niger, Gz Gibberella zeae, Kl Kluyveromyces lactis, Nc Neurospora crassa, Hs Homo sapiens, Sc Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sp Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

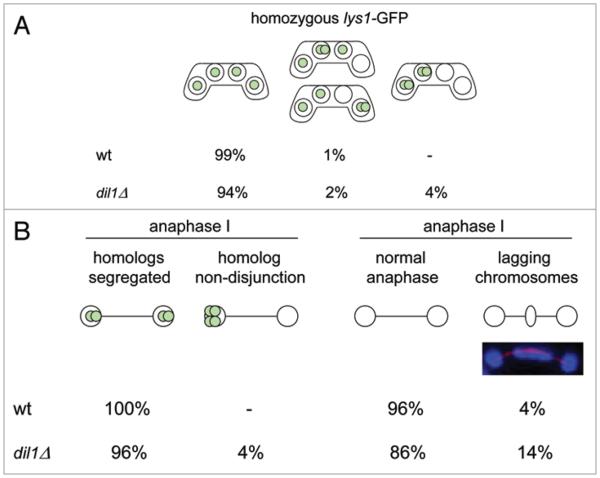

In synchronous pat1-induced meiosis, dil1Δ mutant cells underwent both meiotic divisions with kinetics similar to wild type (Fig. S2). Analysis of lys1-GFP dots in mature asci of strains carrying homozygous lys1-GFP indicated meiosis I homolog non-disjunction in dil1Δ mutant cells (Fig. 3A). To investigate chromosome segregation directly in anaphase I cells, we fixed cells and stained with antibodies against tubulin and GFP. During anaphase I, homologous centromeres in wild-type cells segregate to opposite poles. However, we frequently observed lagging chromosomes and homolog non-disjunction in dil1Δ anaphase I cells (Fig. 3B). Missegregation of homologs during meiosis I could be caused either by a defective recombination leading to a failure to produce chiasmata or by defective sister-chromatid cohesion along chromosome arms. To analyze sister chromatid cohesion, we used a strain in which both copies of chromosome II contained cut3 sequences marked with GFP (cut3-GFP).24 The strain expressed a mutant version of cohesin's α-kleisin subunit (rec8-RDRD) that is resistant to separase cleavage and blocks meiotic divisions.25 The strain also contained a mes1-B44 mutation which prevents reaccumulation of the Cdc13 cyclin and any attempt to undergo meiosis II.26 This strain produces uninucleate meiotic cells with sister chromatids cohesed as indicated by one or two cut3-GFP dots. Defects in sister-chromatid cohesion along chromosome arms are expected to result in cells with more than two cut3-GFP dots. Indeed, almost 60% of cells contained more than two cut3-GFP dots in a strain deleted for rec11, which is known to negatively affect sister-chromatid cohesion along chromosome arms.27 This indicates that the system is efficient in detecting defective cohesion. Consistent with previous reports, sister chromatid cohesion was intact in rec12Δ mutant cells that do not initiate meiotic recombination.6,27 Deletion of dil1 did not increase the appearance of cells with more than two cut3-GFP dots, suggesting that sister chromatid cohesion along chromosome arms is intact in these mutants (Fig. S3). Moreover, deletion of dil1 permitted a small fraction of mes1-B44 mutant cells to undergo nuclear division, which is consistent with the observed homolog non-disjunction phenotype (data not shown). We next compared meiotic recombination in wild-type and dil1Δ mutant cells. Both intergenic and intragenic recombination was moderately reduced in dil1Δ mutant cells (Table 1). These data suggest that homolog non-disjunction observed in dil1Δ mutant cells is due to a defect in recombination but not sister-chromatid cohesion.

Figure 3.

Dil1 is required for proper segregation of chromosomes during meiosis. (A) Meiotic segregation of chromosome I was scored in a wild-type h90lys1-GFP strain (K11248) and h90lys1-GFP strains carrying the knockout allele of dil1 (dil1Δ) (JG14997). Unfixed cells were stained with Hoechst and examined under the fluorescence microscope. Chromosome segregation was scored in at least 100 asci. (B) Strains as described in (A) were fixed and immunostained for tubulin and GFP. DNA was visualized by Hoechst staining. 100 anaphase I cells were examined under the fluorescence microscope and segregation of chromosome I marked by lys1-GFP was scored.

Table 1.

Meiotic recombination is reduced in the absence of dil1+

| Intergenic recombination | |

| Prototrophic recombinants/100 viable spores |

his4-lys4 |

| dil1+ (JG14960 × JG14961) | 5 ± 0.4a |

| dil1Δ (JG15605 × JG15606) | 2.2 ± 0.4a |

| Intragenic recombination | |

| Prototrophic recombinants/100,000 viable spores | ade6-M375 × ade6-52 |

| dil1+ (JG14960 × JG14961) | 4.5 ± 0.8a |

| dil1Δ (JG15605 × JG15606) | 1.6 ± 0.4a |

| Spore viability | |

| dil1+ (JG14960 × JG14961) | 88% |

| dil1Δ (JG15605 × JG15606) | 65% |

Standard error of the mean was calculated from three independent experiments.

Dil1 acts in the dynein pathway to promote oscillatory nuclear movement and efficient pairing of homologous centromeres during meiotic prophase

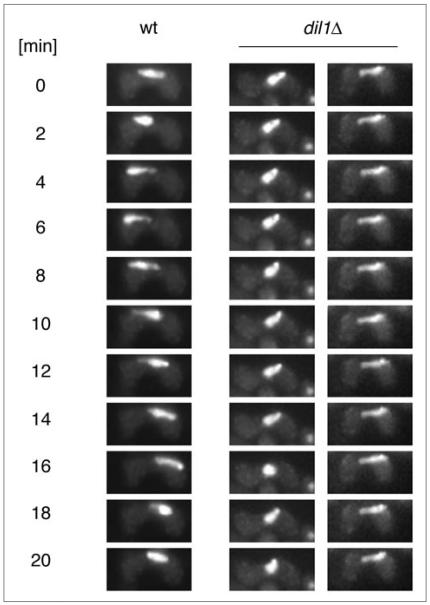

Dynein-driven meiotic oscillatory nuclear movement is known to play a central role in recombination and pairing of homologs.20,28-31 The nuclear movement during meiotic prophase in fission yeast results in a typical horsetail shape of nuclei. We observed a reduced number of horsetail nuclei as well as defect in pairing of homologous centromeres in dil1Δ mutant cells (Table 2) suggesting that Dil1 may be required for the horsetail nuclear movement during meiotic prophase. Live cell imaging showed that indeed, horsetail movement was impaired in 22 out of 24 dil1Δ mutant cells (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Nuclear morphology and number of lys1-GFP dots scored in uninuclear zygotes

| Horsetail shape of the nucleus |

Regular shape of the nucleus |

1 lys1- GFP dot |

2 lys1- GFP dots |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt (K11248) | 74 % | 26 % | 54 % | 46 % |

| dil1Δ (JG14997) | 54 % | 46 % | 27 % | 73 % |

Figure 4.

Dil1 is required for meiotic oscillatory nuclear movement. The dynamics of meiotic horsetail nuclei in the wild-type (K11248) and the dil1Δ cells (JG14997) (two examples are shown) was followed by time-lapse observation. The numbers indicate time in minutes. We observed impairment of the oscillatory nuclear movement n dil1Δ mutant cells, although some nuclei assumed the horsetail shape.

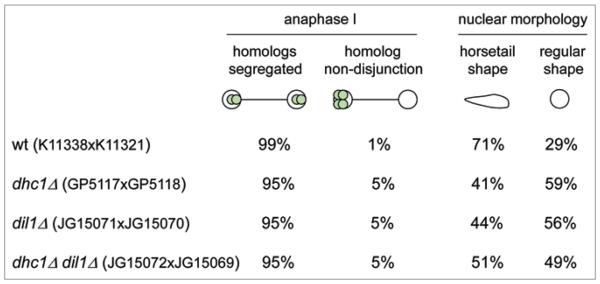

Cytoplasmic dynein is a microtubule motor that drives meiotic nuclear movement.28-30,32 The heavy chains of cytoplasmic dynein contain both ATPase and microtubule binding activities. We further asked whether Dil1 acts in dynein pathway by analyzing genetic interaction of the dil1 with the dhc1, encoding dynein heavy chain.19,28 Homolog non-disjunction phenotype and nuclear morphology of the double mutant dil1Δ dhc1Δ resembled that of single mutants suggesting that the Dil1 acts in the same pathway as Dhc1 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of chromosome segregation in dil1Δ dhc1Δ double mutant. The indicated h− lys1-GFP strains were crossed to a corresponding h+ lys1-GFP strains. Cells were fixed and stained with antibodies against tubulin and GFP. DNA was visualized by Hoechst staining. 100 anaphase I cells were examined under the fluorescence microscope and segregation of chromosome I marked by lys1-GFP was scored.

Similarly as the dynein complex, Dil1 protein localizes to the cytoplasm in cycling cells.33 We observed that Dil1-TAP localized to the leading edge of the horsetail nucleus, where the spindle pole body (SPB) is expected, and to the leading microtubules (Fig. S4). In cycling cells, Dil1-TAP formed foci which distributed asymmetrically during cell division (Fig. S4). A similar phenomenon has been described for the budding yeast dynein.34,35 Thus, Dil1 and dynein display similar localization pattern, raising the possibility that Dil1 may directly interact with dynein. To analyze if Dil1 is physically associated with the dynein complex, we purifed Dil1-TAP from cycling cells. Mass-spectrometry revealed that Dil1-TAP co-purified with several proteins whose function in nuclear movement has not been analyzed, but not with dynein (Table 3). This suggests that Dil1 either does not bind to dynein or binds only loosely. Further analysis of proteins co-purifying with Dil1 will be important to fully understand the function of Dil1. Identification of proteins interacting with Dil1 during meiosis may shed light on the role of Dil1 in the horsetail nuclear movement. However, our attempts to purify Dil1-TAP from meiotic culture failed.

Table 3.

List of proteins identified by mass spectrometry co-purifying with S. pombe Dil1-TAP

| Accession number |

Description | Mascot score |

Molecular weight [kDa] |

Number of peptides assigned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19115610 | Dil1 (sequence orphan) |

180 | 49.1 | 11 |

| 19115897 | multidomain vesicle coat component Sec16 |

138 | 218.3 | 8 |

| 19112952 | conserved fungal protein |

77 | 14.6 | 4 |

| 19115783 | GTP ase activating protein Rga3 |

74 | 110.1 | 5 |

| 19112432 | AAA family ATP ase Rvb2 |

65 | 51.7 | 2 |

| 19113091 | actin cytoskeletal protein Syp1 |

64 | 90.9 | 2 |

| 19112502 | sterol binding ankyrin repeat protein |

44 | 148.6 | 3 |

| 19115105 | dipeptidyl aminopeptidase |

41 | 46.1 | 2 |

| 19114566 | exocyst complex subunit Sec10 |

34 | 92.8 | 3 |

Only proteins identified with more than two peptides are included. Proteins found in other unrelated purifications are omitted from this table.

Taken together, we show that Dil1 acts in the dynein pathway to promote oscillatory nuclear movement which is essential for efficient pairing of homologous centromeres and recombination during meiosis.

Discussion

The strategy of knocking-out genes upregulated during meiosis proved to be efficient in identifying key regulators of meiotic chromosome segregation. In fission yeast, such strategy led to the identification of the long sought-after protector of centromeric cohesion Sgo1 and a new protein required for the initiation of meiotic recombination Mde2.6,7 Martin-Castellanos et al. identified three mutants (rec24, rec25 and rec27) with reduced meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breakage, one mutant (tht2) deficient in karyogamy, and two mutants (bqt1 and bqt2) deficient in telomere clustering.8 A similar approach in budding yeast identified Mam1 component of the monopolin complex, Mnd1 recombination protein and Mnd2 subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C).36-38 In our current study we report the identification of a novel gene, dil1+, required for faithful segregation of chromosomes during meiosis. We establish that Dil1 acts in the dynein pathway to promote oscillatory nuclear movement, which is known to be required for pairing of homologous centromeres and recombination during meiosis. Recombination leads to formation of chiasmata which physically link homologous chromosomes. This linkage is essential for faithful segregation of chromosomes during meiosis I.2 In many model organisms studied so far, disturbances in the recombination pathway are frequently associated with abnormalities in chromosome segregation at meiosis I.39 Defective recombination is therefore likely to be the cause of homolog non-disjunction observed in dil1Δ mutant cells. Our analysis revealed that Dil1 shares sequence similarity with dynein light intermediate chain proteins (DLIC), indicating that Dil1 may be a fission yeast counterpart of the DLIC proteins. Dynein-dependent nuclear movements play important roles in both yeasts and higher eukaryotes (reviewed in refs. 32 and 40-43), suggesting that the basic mechanism regulating dynein-dependent nuclear movements may be conserved in evolution. Finally, greater knowledge of the processes that promote proper segregation of chromosomes during meiosis might help us to understand the origins of human meiotic aneuploidy, the leading cause of miscariages and genetic disorders such as Down syndrome.39

Materials and Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

The genotypes of S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in the Table S2. Genes were deleted according to knockout protocol described in.9 S. pombe media and growth conditions were as described in reference 7. Spore viability and recombination analysis was performed as described in reference 44.

Microscopy

The immunofluorescence and microscopy techniques used to analyze chromosome segregation were as described in reference 7.

Live cell imaging

For time-lapse observations of living cells a Zeiss Axio Imager equipped with a digital spot camera (Visitron System) was used. Cells were sporulated on PMG-N plates for 20 hours, resuspended in 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 and incubated for 15 min. 3 μl of stained cells were mixed with 6 μl of PMG-N medium containing 1% low melt agarose and mounted on a coverslip. The coverslip was placed on a microscope slide and sealed with hot Vaseline. Each time series of images was obtained with a 0.1-s exposure at 2 min intervals under low fluorescence excitation conditions to limit bleaching (BFP filter).

Protein purification

8-liter cultures of strains expressing TAP-tagged proteins were grown to log phase and the tagged proteins were isolated as described previously.45,46

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed as described previously.47

Sequence analysis and protein database searches

In the current S. pombe genome database17 SPAC458.04c is listed as an orphan sequence with no known sequence domains and a distinctive upregulation during the meiotic cell cycle. While in the up-to-date NCBI non-redundant protein database48 SPAC458.04c indeed lacks clear homologs (with E < 0.001), orthologs can be readily identified in the genomic sequence of Schizosaccharomyces octosporus and Schizosaccharomyces sp. OY26 (www.broad.mit.edu). Using these orthologous sequences and a number of sensitive computational tools we can demonstrate the sequence similarity of SPAC458.04c to the family of dynein light intermediate chain (DLIC) proteins.

When applying the S. pombe SPAC458.04c protein sequence as a query to available profile-based similarity methods the following links to the dynein light intermediate chain (DLIC) family are obtained: (1) FFAS03,49 reports DLIC/PF05783.2 as the top and only profile with significant similarity to SPAC458.04c with a score of −10.7 (scores below −9.5 are considered significant by FFAS03) (2) HHpred50 and CD-search list the similarity to DLIC/PF05783.2 as the top, and by far best hit with E-value of 0.043 and 0.1, respectively. These initial indications of a SPAC458.04c-DLIC similarity are strongly reinforced, when the S. octosporus full-length homolog of SPAC458.04c is applied to FFAS03 and HHpred queries. In these searches DLIC/PF05783.2 is the top and only significant hit obtained with a FFAS03 score of −50 and E-value of 5.6e-44, respectively. Highly significant hits to the DLIC family are also obtained when using S. pombe SPAC458.04c itself in a PSI-BLAST search against the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database (Dec 2007) supplemented by the S. octosporus SPAC458.04c. The first fungal DLIC homologs are retrieved in round 2 of the PSI-BLAST search, and are followed by various metazoan homologs in round 3. The PSI-BLAST remains in the DLIC family until its convergence in round 11 and collects homologs from a broad range of taxa including apicomplexans, kinetoplastids, ciliates, green algae, cellular slime molds, trichomonads. Conservation within the family is particularly high in the central part of the proteins. An alignment of representative sequences of the fungal/metazoan DLIC group is shown in Figure S1.

The de-novo gene prediction of S. OY26 SPAC458.04c extends further N-terminally than the publicly available S. pombe SPAC458.04c (NP_594698.1). The extended N-terminal segment of S. OY26 seems to be confirmed by similarity to other DLIC family members and can be used to extend the publicly available S. pombe SPAC458.04c protein sequence. While all sequence analyses were performed with the publicly available SPAC458.04c variant, the extended variant is shown in Figure S1.

It has been previously noted that DLIC proteins show similarity to P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases.51 In addition the protein family DLIC/PF05783.4 has been assigned to the Pfam AAA Clan (CL0023) of P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases. For a more precise protein classification HHpred searches are performed with individual DLIC members against the hierarchically structured SCOP and NCBI-CD databases. PSI-BLAST iterations within HHpred are restricted to a minimal number ensuring that a DLIC-specific model is used by the method. HHpred searches against the SCOP database indicate that DLIC proteins belong to the structural family of G proteins (c.37.1.8). Notable among the top hits is the domain model of Spg1/Tem1 GTPases (cd04128)—a protein family that is also encountered in BLAST and PSI-BLAST searches using LIC3 family members. For further details and search results see http://mendel.imp.ac.at/SEQUENCES/DLIC/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank K. Gull and G. Smith for sending us strains and reagents, G. Smith, S. Moreno, F. Klein, M. Spirek and J. Loidl for helpful discussions and M. Siomos for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by FWF grants (P18955, P20444, F3403) and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number PIEF-GA-2008-220518. C.R. was supported by the F-343 stipendium from the University of Vienna. I.K. was supported by the grant CD-2009-35521/37347-1:11 from the Ministry of Education. A.D. is on leave from Cancer Research Institute, Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, 83391, Bratislava, Slovak Republic supported by the FWF Lise Meitner Program M1145.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/RumpfCC9-9-Sup.pdf

References

- 1.Paliulis LV, Nicklas RB. The reduction of chromosome number in meiosis is determined by properties built into the chromosomes. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1223–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petronczki M, Siomos MF, Nasmyth K. Un menage a quatre: the molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell. 2003;112:423–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page SL, Hawley RS. Chromosome choreography: the meiotic ballet. Science. 2003;301:785–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1086605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregan J, Spirek M, Rumpf C. Solving the shugoshin puzzle. Trends Genet. 2008;24:205–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pidoux AL, Allshire RC. The role of heterochromatin in centromere function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:569–79. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregan J, Rabitsch PK, Sakem B, Csutak O, Latypov V, Lehmann E, et al. Novel genes required for meiotic chromosome segregation are identified by a high-throughput knockout screen in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1663–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabitsch KP, Gregan J, Schleiffer A, Javerzat JP, Eisenhaber F, Nasmyth K. Two fission yeast homologs of Drosophila Mei-S332 are required for chromosome segregation during meiosis I and II. Curr Biol. 2004;14:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Castellanos C, Blanco M, Rozalen AE, Perez-Hidalgo L, Garcia AI, Conde F, et al. A large-scale screen in S. pombe identifies seven novel genes required for critical meiotic events. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2056–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregan J, Rabitsch PK, Rumpf C, Novatchkova M, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K. High-throughput knockout screen in fission yeast. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2457–64. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Bahler J. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat Genet. 2002;32:143–7. doi: 10.1038/ng951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krawchuk MD, Wahls WP. High-efficiency gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using a modular, PCR-based approach with long tracts of flanking homology. Yeast. 1999;15:1419–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990930)15:13<1419::AID-YEA466>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma P, Winderickx J, Nauwelaers D, Dumortier F, De Doncker A, Thevelein JM, et al. Deletion of SFI1, a novel suppressor of partial Ras-cAMP pathway deficiency in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, causes G(2) arrest. Yeast. 1999;15:1097–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199908)15:11<1097::AID-YEA437>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nabeshima K, Nakagawa T, Straight AF, Murray A, Chikashige Y, Yamashita YM, et al. Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3211–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi Y, Saitoh S, Ogiyama Y, Soejima S, Takahashi K. The fission yeast DASH complex is essential for satisfying the spindle assembly checkpoint induced by defects in the inner-kinetochore proteins. Genes Cells. 2007;12:311–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon HJ, Feoktistova A, Chen JS, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Gould KL. Role of Hcn1 and its phosphorylation in fission yeast anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32284–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasama T, Shigehisa A, Hirata A, Saito TT, Tougan T, Okuzaki D, et al. Spo5/Mug12, a putative meiosis-specific RNA-binding protein, is essential for meiotic progression and forms Mei2 dot-like nuclear foci. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1301–13. doi: 10.1128/EC.00099-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertz-Fowler C, Peacock CS, Wood V, Aslett M, Kerhornou A, Mooney P, et al. GeneDB: a resource for prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:339–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K, et al. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:214–29. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis L, Smith GR. Dynein promotes achiasmate segregation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2005;170:581–90. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.040253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chikashige Y, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Another way to move chromosomes. Chromosoma. 2007;116:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hook P, Vallee RB. The dynein family at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4369–71. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wickstead B, Gull K. Dyneins across eukaryotes: a comparative genomic analysis. Traffic. 2007;8:1708–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoder JH, Han M. Cytoplasmic dynein light intermediate chain is required for discrete aspects of mitosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2921–33. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabeshima K, Kakihara Y, Hiraoka Y, Nojima H. A novel meiosis-specific protein of fission yeast, Meu13p, promotes homologous pairing independently of homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2001;20:3871–81. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitajima TS, Miyazaki Y, Yamamoto M, Watanabe Y. Rec8 cleavage by separase is required for meiotic nuclear divisions in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2003;22:5643–53. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izawa D, Goto M, Yamashita A, Yamano H, Yamamoto M. Fission yeast Mes1p ensures the onset of meiosis II by blocking degradation of cyclin Cdc13p. Nature. 2005;434:529–33. doi: 10.1038/nature03406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitajima TS, Yokobayashi S, Yamamoto M, Watanabe Y. Distinct cohesin complexes organize meiotic chromosome domains. Science. 2003;300:1152–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1083634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto A, West RR, McIntosh JR, Hiraoka Y. A cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain is required for oscillatory nuclear movement of meiotic prophase and efficient meiotic recombination in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1233–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel SK, Pavin N, Maghelli N, Julicher F, Tolic-Norrelykke IM. Self-organization of dynein motors generates meiotic nuclear oscillations. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:1000087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miki F, Okazaki K, Shimanuki M, Yamamoto A, Hiraoka Y, Niwa O. The 14-kDa dynein light chain-family protein Dlc1 is required for regular oscillatory nuclear movement and efficient recombination during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:930–46. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding DQ, Yamamoto A, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Dynamics of homologous chromosome pairing during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Dev Cell. 2004;6:329–41. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore JK, Stuchell-Brereton MD, Cooper JA. Function of dynein in budding yeast: mitotic spindle positioning in a polarized cell. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2009;66:546–55. doi: 10.1002/cm.20364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuyama A, Arai R, Yashiroda Y, Shirai A, Kamata A, Sekido S, et al. ORFeome cloning and global analysis of protein localization in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:841–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grava S, Schaerer F, Faty M, Philippsen P, Barral Y. Asymmetric recruitment of dynein to spindle poles and microtubules promotes proper spindle orientation in yeast. Dev Cell. 2006;10:425–39. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw SL, Yeh E, Maddox P, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:985–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabitsch KP, Petronczki M, Javerzat JP, Genier S, Chwalla B, Schleiffer A, et al. Kinetochore recruitment of two nucleolar proteins is required for homolog segregation in meiosis I. Dev Cell. 2003;4:535–48. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabitsch KP, Toth A, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Schaffner G, Aigner E, et al. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1001–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toth A, Rabitsch KP, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Buonomo SB, Nasmyth K. Functional genomics identifies monopolin: a kinetochore protein required for segregation of homologs during meiosis i. Cell. 2000;103:1155–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassold T, Hall H, Hunt P. The origin of human aneuploidy: where we have been, where we are going. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:203–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallee RB, Seale GE, Tsai JW. Emerging roles for myosin II and cytoplasmic dynein in migrating neurons and growth cones. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:347–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gennerich A, Vale RD. Walking the walk: how kinesin and dynein coordinate their steps. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tolic-Norrelykke IM. Force and length regulation in the microtubule cytoskeleton: lessons from fission yeast. Curr Opin Cell Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto A, Hiraoka Y. Cytoplasmic dynein in fungi: insights from nuclear migration. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4501–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spirek M, Estreicher A, Csaszar E, Wells J, McFarlane RJ, Watts FZ, et al. SUMOylation is required for normal development of linear elements and wild-type meiotic recombination in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Chromosoma. 119:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s00412-009-0241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riedel CG, Katis VL, Katou Y, Mori S, Itoh T, Helmhart W, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A protects centromeric sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I. Nature. 2006;441:53–61. doi: 10.1038/nature04664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cipak L, Spirek M, Novatchkova M, Chen Z, Rumpf C, Lugmayr W, et al. An improved strategy for tandem affinity purification-tagging of Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes. Proteomics. 2009;9:4825–8. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gregan J, Riedel CG, Petronczki M, Cipak L, Rumpf C, Poser I, et al. Tandem affinity purification of functional TAP-tagged proteins from human cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1145–51. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wheeler DL, Chappey C, Lash AE, Leipe DD, Madden TL, Schuler GD, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:10–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaroszewski L, Rychlewski L, Li Z, Li W, Godzik A. FFAS03: a server for profile—profile sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:284–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:244–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grissom PM, Vaisberg EA, McIntosh JR. Identification of a novel light intermediate chain (D2LIC) for mammalian cytoplasmic dynein 2. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:817–29. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.