Abstract

Intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytomas are rare tumors that can mimic meningioma on imaging and on histopathology. However, these tumors are more aggressive with a tendency for local and metastatic recurrence, sometimes after a prolonged symptom-free interval. We report an unusual metastatic recurrence of an intracranial hemangiopericytoma, 8 years after surgery for the primary tumor and discuss the role of positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the follow-up of these patients.

Keywords: Intracranial hemangiopericytoma, extracranial metastases, PET/CT, follow-up, 8 years

Introduction

Hemangiopericytomas are rare aggressive tumors with a tendency for local and metastatic recurrence[1]. Resection of metastases however has been reported to improve survival[7-10]. Exclusion of multiplicity of metastases prior to surgery is thus vital. We discuss the detection of an unusual disseminated metastatic recurrence of an intracranial hemangiopericytoma 8 years after surgery on positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT), its impact on clinical management and explore its possible role in the follow-up of these patients in the future.

Case report

A 21-year-old man presented in 2001 with headache, tinnitus, intermittent nausea and vomiting for 6 months. There were no signs/symptoms of lower cranial nerve palsy. There was no history of trauma, tuberculosis or fever. A neurological examination revealed bilateral papilledema and right cerebellar signs.

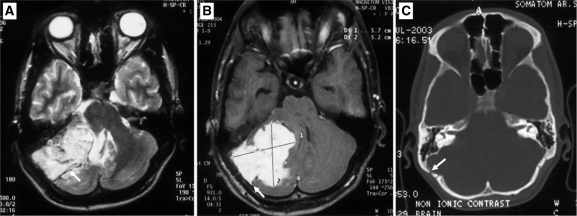

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an infratentorial, lobulated extra-axial mass with a wide dural base, which showed an isointense signal on T1-weighted images, and heterogeneous signal on T2-weighted images with prominent flow voids (Fig. 1A). It showed intense, homogenous contrast enhancement and a dural tail (Fig. 1B). Associated thinning and scalloping of the underlying bone (Fig. 1C) was also noted on the CT scan. On the basis of imaging, a diagnosis of an atypical meningioma was suspected and the patient underwent a right retromastoid suboccipital craniotomy which revealed a grayish-white, lobulated, vascular tumor. There was a well-defined cleavage plane between the tumor and the cerebellum which aided total excision of the lesion along with the dura and underlying bone. Histopathological examination of the tumor was suggestive of hemangiopericytoma (HPC).

Figure 1.

Axial T2-weighted (A), contrast-enhanced T1-weighted and CT image in bone window through the posterior fossa. (A) A lobulated mass is seen showing a heterogeneous hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images with flow voids within (arrow). (B) Intense enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted image with an associated dural tail (arrow). (C) CT scan revealed thinning and scalloping of the underlying bone (arrow).

He then received stereotactically confirmed external radiation therapy (RT) to a dose of 54 Gy in 30 fractions over 41 days. Following completion of treatment he was asymptomatic and on regular follow-up for about 8 years, when in 2009 he presented with a firm, non-tender swelling on his back on the right side.

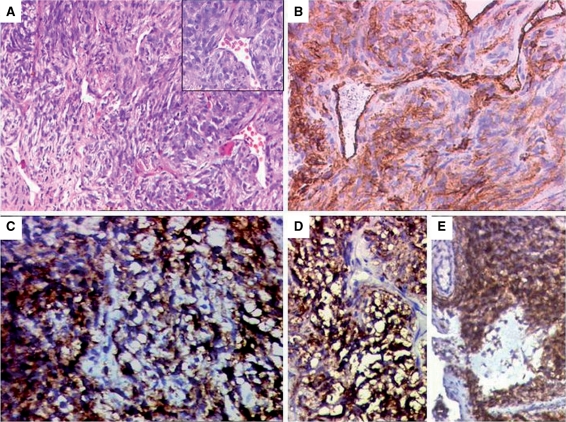

A biopsy of the swelling revealed a spindle cell tumor exhibiting a prominent hemangiopericytomatous pattern (Fig. 2A). On immunohistochemistry (IHC), CD34 highlighted the stag horn vasculature with patchy positivity within the tumor (Fig. 2B). The tumor cells were also diffusely positive for vimentin, MIC2 (Fig. 2C), BCL2 (Fig. 2D) and calponin. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) was focally weakly positive (Fig. 2E). In view of the soft tissue location of the tumor and its histopathological features (including IHC profile), a differential diagnoses of a synovial sarcoma and a metastatic hemangioperictyoma were considered. Translocation studies were recommended for SYT-SSX analysis by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique to discriminate between the two. The negative results ruled out a synovial sarcoma and a final diagnosis of HPC was offered in the overall clinicopathological context.

Figure 2.

Histopathologic features of a hemangiopericytoma. (A) Tumor from the back showing spindly cells exhibiting stag horn vasculature. Inset highlighting stag horn shaped vessels. Immunohistochemical results: (B) CD34 positivity in patchy areas of the tumor; (C) MIC2 positivity in tumor cells; (D) tumor cells displaying BCL2 positivity; (E) focal areas showing positive EMA expression.

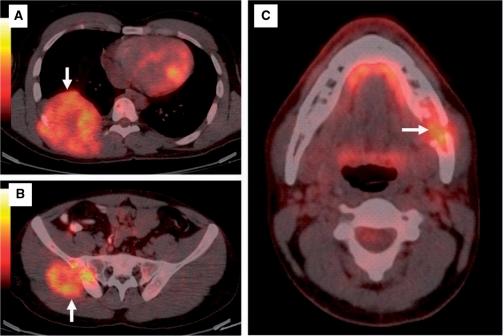

The patient then underwent a PET/CT study which revealed multiple asymptomatic osseous lesions with associated soft tissue masses involving the right-sided chest wall (Fig. 3A), right hemipelvis (Fig. 3B), left hemimandible (Fig. 3C) with abnormal tracer accumulation in the right femur and the left humerus. There was no recurrence at the primary site. In view of disseminated metastatic disease the patient was advised palliative RT and is being followed up.

Figure 3.

Fusion PET/CT images show metastatic osseous lesions (arrows) with associated soft tissue masses in the right posterior chest wall (A), right hemipelvis (B) and the left hemimandible (C).

Discussion

HPCs are rare tumors that arise from the Zimmerman pericytes, cells surrounding the capillary and postcapillary venules. Most HPCs occur in the musculoskeletal system and the skin. Those located in the central nervous system are rare and meningeal HPCs account for <2.5 % of all meningeal tumors and <1% of all intracranial tumors. Headache is the commonest presenting symptom in meningeal HPCs. A slight male preponderance is reported, with most cases occurring in the middle-aged group[1–3].

On imaging, most intracranial HPCs are supratentorial in distribution; the commonest location is the parasaggital area[1]. Almost all tumors have lobulated margins and are dense on CT. HPCs appear predominantly isointense on T1- and T2-weighted images and show marked contrast enhancement on CT and MRI. Unlike meningiomas, HPCs do not show calcification or associated hyperostosis of the underlying bone. On the contrary HPCs have been reported to show bone erosion. These features help in radiological differentiation of the two entities, which otherwise occur at similar intracranial sites[4].

Histopathologically HPC shows a stag horn vascular pattern of spindly cells. At times, the histopathologic features of a HPC and meningioma can overlap. IHC is vital in differentiating these two entitles. Classically, while HPC shows positivity for CD 34, a meningioma is EMA positive. Focal positivity of EMA in a HPC is also known[5].

The cornerstone of treatment in patients with meningeal HPCs is complete resection of the tumor with the underlying dura and bone. Addition of postoperative radiotherapy is the norm and has shown a significant reduction in rate of local recurrence when compared with surgery alone[6]. However, HPCs are inherently aggressive and tend to recur locally and distally, with extraneural metastatic recurrence reported in as many as 23% of cases[1]; the commonest sites are the lungs and the bones.

Radical surgical treatment of metastasis has shown improved survival and is being increasingly used[7–10] in patients with metastatic disease. This brings into focus the role played by imaging in excluding other metastatic sites prior to surgery for seemingly isolated metastasis. In the setting of recurrent disease, locoregional imaging of the clinically suspected site is usually performed with relatively less emphasis on whole body imaging. Thus, the onus of exclusion or confirmation of recurrence has so far been with conventional locoregional imaging modalities. Our patient presented with a solitary swelling in the back, which in fact was only a part of disseminated metastatic disease uncovered by whole body PET/CT imaging. This precluded a possible resection of the chest wall tumor and put the patient on palliative therapy.

Suzuki et al.[11] presented a report of an intracranial HPC with extracranial metastases and reviewed 19 cases from the available literature. Multiple sites of metastases were seen in 9/20 cases. Similar findings have also been described by others, in which the patients had multiple sites of metastases separated from each other in time and anatomic location[7,8,10,12]. Multiple metastases were also seen in our patient. In addition, in lieu of asymptomatic metastases as seen in our case, it is a reasonable step to subject patients treated for HPC to whole body imaging modalities like PET/CT to assess feasibility or futility of radical surgery. Our case thus highlights the role of PET/CT in uncovering the multiplicity of metastatic recurrence even in tumors like HPC, which are not routinely imaged with PET. A few isolated reports[13–15] have described the PET/CT findings of HPC at initial presentation; however, its value in the setting of recurrence and restaging as described in our report has not been studied hitherto. Whether or not PET/CT can make an impact on deciding the management of patients with recurrent HPCs as described in our case remains to be seen and certainly merits validation with larger prospective studies.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW, Shaw EG. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: histopathological features, treatment, and long-term follow-up of 44 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:514–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jääskeläinen J, Servo A, Haltia M, Wahlström T, Valtonen S. Intracranial hemangiopericytoma: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy, and outcome in 21 patients. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:227–36. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufour H, Métellus P, Fuentes S, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: a retrospective study of 21 patients with special review of postoperative external radiotherapy. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:756–63. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200104000-00011. doi:10.1097/00006123-200104000-00011. PMid:11322435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiechi MV, Smirniotopoulos JG, Mena H. Intracranial hemangiopericytomas: MR and CT features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1365–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajaram V, Brat DJ. Anaplastic meningioma versus meningeal hemangiopericytoma: immunohistochemical and genetic markers. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1413–18. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.07.017. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2004.07.017. PMid:15668900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soyuer S, Chang EL, Selek U, McCutcheon IE, Maor MH. Intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytoma: the role of radiotherapy: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 2004;100:1491–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20109. doi:10.1002/cncr.20109. PMid:15042684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita I, Kiyama T, Chou K, Kanno H, Naito Z, Uchida E. A case of metastatic hemangiopericytoma occurring 16 years after initial presentation: with special reference to the clinical behavior and treatment of metastatic hemangiopericytoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2009;76:221–5. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.221. doi:10.1272/jnms.76.221. PMid:19755799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiefer T, Wertzel H, Freudenberg N, Hasse J. Long-term survival after repetitive surgery for malignant hemangiopericytoma of the lung with subsequent systemic metastases: case report and review of the literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;45:307–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013754. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1013754. PMid:9477464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brega Massone PP, Lequaglie C, Conti B, Ferro F, Magnani B, Cataldo I. A particular case with long-term follow-up of rare malignant hemangiopericytoma of the lung with metachronous diaphragmatic metastasis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50:178–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32407. doi:10.1055/s-2002-32407. PMid:12077693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spatola C, Privitera G. Recurrent intracranial hemangiopericytoma with extracranial and unusual multiple metastases: case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 2004;90:265–8. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H, Haga Y, Oguro K, Shinoda S, Masuzawa T, Kanai N. Intracranial hemangiopericytoma with extracranial metastasis occurring after 22 years. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2002;42:297–300. doi: 10.2176/nmc.42.297. doi:10.2176/nmc.42.297. PMid:12160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshi M, Araki N, Naka N, et al. Bone metastasis of intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:208–13. doi: 10.1007/s10147-005-0476-y. doi:10.1007/s10147-005-0476-y. PMid:15990973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kracht LW, Bauer A, Herholz K, et al. Positron emission tomography in a case of intracranial hemagiopericytoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:365–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199905000-00008. doi:10.1097/00004728-199905000-00008. PMid:10348440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khadgawat R, Singh Y, Kansara S, et al. PET/CT localization of a scapular hemangiopericytoma with tumor-induced osteomalacia. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:e55–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams HT, Gossage JR, Jr, Allred TJ, Kallab AM, Pancholy A, Anstadt MP. F-18 FDG positron emission tomography imaging of rare soft tissue sarcomas: low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and malignant hemangiopericytoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29:581–4. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000134996.94657.e2. doi:10.1097/01.rlu.0000134996.94657.e2. PMid:15311133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]