Synopsis

Naturopathy is a distinct type of primary care medicine that blends age-old healing traditions with scientific advances and current research. It is guided by a unique set of principles that recognize the body's innate healing capacity, emphasize disease prevention, and encourage individual responsibility to obtain optimal health. Naturopathic treatment modalities include diet and clinical nutrition, behavioral change, hydrotherapy, homeopathy, botanical medicine, physical medicine, pharmaceuticals, and minor surgery. Naturopathic physicians (NDs) are trained as primary care physicians in four-year, accredited doctoral-level naturopathic medical schools. Currently, there are 15 U.S. states, 2 U.S. territories, and a number of provinces in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand that recognize licensure for NDs.

Keywords: naturopathic, naturopathy, nutrition, botanical medicine, homeopathy, hydrotherapy

Naturopathic Medicine Overview

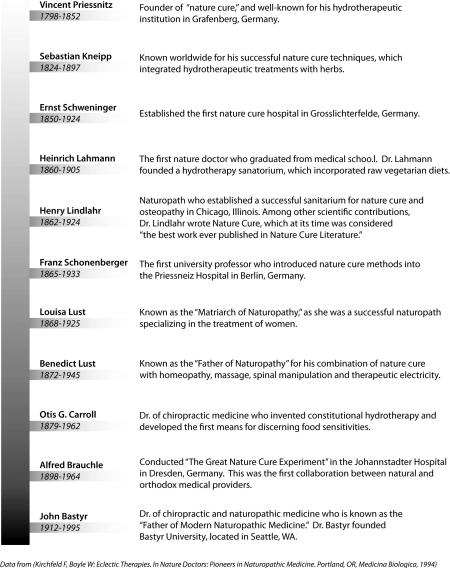

Naturopathy is a distinct type of primary care medicine that blends age-old healing traditions with scientific advances and current research. It is guided by a unique set of principles that recognize the body's innate healing capacity, emphasize disease prevention, and encourage individual responsibility to obtain optimal health (List 1). The naturopathic physician (ND) strives to thoroughly understand each patient's condition, and views symptoms as the body's means of communicating an underlying imbalance. Treatments address the patient's underlying condition, rather than individual presenting symptoms. Modalities utilized by NDs include diet and clinical nutrition, behavioral change, hydrotherapy, homeopathy, botanical medicine, physical medicine, pharmaceuticals, and minor surgery1, 2. Naturopathy can be traced back to the European “nature cure,” practiced in the nineteenth-century, which was a system for treating disease with natural modalities such as water, fresh air, diet, and herbs. In the early twentieth-century, naturopathy developed in the U.S. and Canada, combining nature cure, homeopathy, spinal manipulation and other therapies (Timeline)3.

Naturopathic Approach to Health

In naturopathic theory, illness is viewed as a process of disturbance to health and subsequent recovery in the context of natural systems. Many things can disturb optimal health, such as poor nutrition, chronic stress, or toxic exposure. The goal of the ND is to restore health by identifying and minimizing these disturbances. In order to do this, the ND first recognizes the factors that determine health (Table 1). A determinant becomes a disturbance when it is compromised in some way.

Table 1.

| Determinants of Health | |

|---|---|

| Inborn | Genetic Makeup (genotype) |

| Intrauterine/Congenital | |

| Maternal Exposures | |

| – Drugs | |

| – Toxins | |

| – Viruses | |

| – Psychoemotional | |

| Maternal Nutrition | |

| Maternal Lifestyle | |

| |

Constitution- determines susceptibility |

| Hygenic Factors/Lifestyle Factors – How We Live | Environment, Lifestyle, Psychoemotional, and Spiritual Health |

| – Spiritual life | |

| – Self-assessment | |

| – Relationship to larger universe | |

| Exposure to Nature | |

| – Fresh air | |

| – Clean water | |

| – Light | |

| Diet, Nutrition, and Digestion | |

| – Unadulterated food | |

| – Toxemia | |

| Rest and Exercise | |

| – Rest | |

| – Exercise | |

| Socio-economic Factors | |

| – Culture | |

| – Loving and being loved | |

| – Meaningful work | |

| – Community | |

| Stress (Physical, Emotional) | |

| – Trauma (physical/emotional) | |

| – Illnesses: pathobiography | |

| – Medical interventions (or lack of) | |

| – Surgeries | |

| – Suppressions | |

| – Physical and emotional exposures, stresses, and trauma | |

| – Toxic and harmful substances | |

| – Addictions | |

From Zeff J., Snider P, Pizzorno JE. Section I: Philosophy of Natural Medicine. The Textbook of Natural Medicine 3rd ed. 2006;1(1), with permission

In attempting to restore health, the ND follows a specific, yet adaptable, therapeutic order that begins with minimal interventions and proceeds to higher level interventions as necessary (List 2). The order begins with reestablishing the conditions of health, such as developing a more healthful dietary and lifestyle regime. Next, the body's natural healing mechanisms may be stimulated through techniques such as hydrotherapy, which can increase the circulation of blood and lymph. The third step is to support weakened or damaged systems with homeopathy, botanical medicines, or specific exercises, such as yoga. The fourth step is to correct structural integrity, which is typically done with physical medicine techniques including massage and naturopathic manipulation. The fifth step is to address pathology using specific natural substances, such as dietary supplements. The sixth step is to address pathology using pharmaceutical or synthetic substances. Surgical correction is reserved for the final therapeutic step4.

Current Practice

Education

NDs are trained in four-year, accredited doctoral-level naturopathic medical schools. Such schools have been experiencing significant increases in enrollment and graduating class sizes over the past 20 years, particularly since the year 20005. There are currently seven naturopathic medical schools in the US and Canada that are either accredited or are in candidate status for accreditation (Table 2). The range of didactic instruction at these schools is between 2,580 to 3,270 hours, and clinical instruction is between 1,200 to 1,500 hours1, 61.

Table 2.

| Accredited Naturopathic Medical Schools in the U.S and Canada | |

|---|---|

| School | Contact |

| Bastyr University | 14500 Juanita Drive NE Kenmore, WA 98028 http://www.bastyr.edu/ |

| Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine | 300-435 Columbia Street New Westminster, BC V3L 5N8 Canada http://www.binm.org/ |

| Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine | 1255 Sheppard Avenue East Toronto, Ontario M2K 1E2 Canada http://www.ccnm.edu/ |

| National College of Natural Medicine | 049 SW Porter Street Portland, OR 97201 http://www.ncnm.edu/ |

| National University of Health Sciences | 200 E. Roosevelt Road Lombard, Illinois 60148 http://www.nuhs.edu/ |

| Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine | 2140 E. Broadway Road Tempe, AZ 85282 http://www.scnm.edu/ |

| University of Bridgeport | 126 Park Avenue Bridgeport, CT 06604 https://www.bridgeport.edu/ |

Accredited naturopathic medical schools must attain both regional and programmatic accreditation. Regional accreditation is through one of the U.S. Department of Education-recognized regional associations of schools and colleges. Programmatic accreditation for all naturopathic medical schools in North America is through the Council on Naturopathic Medical Education (CNME). All accredited naturopathic medical schools are supported by The Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges (AANMC), which acts to promote the naturopathic profession by ensuring rigorous educational standards7, 8.

Candidates for admission to naturopathic medical school are required to hold a baccalaureate degree, and to have completed all standard premedical undergraduate coursework prior to matriculation. The first 2 years of naturopathic medical education focuses on basic and diagnostic sciences including anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, histology, pathology, embryology, neuroscience, immunology, pharmacology, physical and clinical diagnosis, and lab diagnosis. The final 2 years of naturopathic medical education focuses on clinical sciences and practicum. Coursework specific to naturopathic medicine is woven throughout the program, which includes naturopathic theory, diet and nutrient therapy, botanical medicine, homeopathy, hydrotherapy, massage, naturopathic manipulation, therapeutic exercise, counseling, and case management. Some NDs receive additional training in related disciplines, such as midwifery, Oriental herbal medicine, or acupuncture1, 7. NDs may choose to specialize in certain populations, such as pediatrics, or certain modalities, such as homeopathy.

There are a limited number of 1- to 2-year postdoctoral CNME-certified naturopathic residency programs available. Currently, residency is not required for licensure, except in Utah. Programs are extremely competitive, with an average of 350-400 new ND graduates in the U.S per year and only 30-40 openings. Most of these programs are offered through accredited naturopathic medical schools and affiliated clinics, although other opportunities are emerging. An Integrative Medicine Residency is available through several hospitals and clinics, which gives NDs the opportunity to collaborate with conventional medical practitioners. The naturopathic profession has a commitment to increase clinical training opportunities, including the availability of postdoctoral residencies. There is a common informal practice of mentorship in which a new graduate joins the practice of a senior ND9.

Licensing

The licensing of NDs is determined at the state or province level in countries that regulate the profession. Currently, Alaska, Arizona, British Columbia, California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Manitoba, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, Ontario, Oregon, Saskatchewan, Utah, Vermont, and Washington, the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as provinces in Australia and New Zealand, have licensing laws for NDs2. Licensing efforts for NDs are led by state organizations, and many currently unlicensed states are in various stages of the process towards licensure. Proximity to an already licensed state a significant predictor of new licensure10. In order to be eligible for licensure, an ND must have graduated from an accredited naturopathic medical school, and have passed the Naturopathic Physicians Licensing Examination (NPLEx). NPLEx follows the same standards as the National Board of Medical Examiners (for the USMLE), the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners, and other healthcare professions.11

Licensing laws for NDs increase public safety by ensuring consistency of education, professional standards, compliance with public health standards, appropriate regulation, and currency of continuing education. In states and territories that do not have ND licensing laws, there has been an emergence of unqualified practitioners who did not graduate from appropriately accredited naturopathic medical schools. Licensure in all areas will protect patients by ensuring that the providers they choose have an education in safe practice of naturopathic medicine7.

Scope of practice

NDs are trained as primary care physicians with an emphasis in natural medicine in ambulatory settings. Their scope of practice varies by state and territory, but generally consists of the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disease by stimulation and support of the body's natural healing mechanisms. Standard diagnostic and preventive techniques utilized include physical examination, laboratory testing, and diagnostic imaging. NDs may employ additional laboratory tests and examination procedures for further evaluation of nutritional status, metabolic functioning, and toxicities. Treatment modalities utilized by NDs include diet and clinical nutrition, behavioral change, hydrotherapy, homeopathy, botanical medicine, and physical medicine. Depending upon the state, NDs may also be licensed to perform minor office procedures and surgery, administer vaccinations, and prescribe many prescriptive drugs12.

Insurance credentialing

An increasing number of insurance companies, unions, and state organizations are credentialing licensed NDs. NDs are not credentialed in the same manner that MDs and DOs are since the scope of practice of NDs is not uniform nationwide. The process is based upon each state's individual licensing laws and particulars of each company7, 12. Excessive standardization to cater to credentialing needs may be unfavorable to both NDs and their patients, as individualized care is fundamental to the profession. If the widespread credentialing of NDs is undertaken, a balance between establishing tight practice regulations and allowing for individualized approaches may be necessary13.

NDs have been licensed in Washington State since 1919, and credentialed since 1996. An epidemiologic study found that 1.6% of 600,000 enrollees from 3 major insurance companies in Washington filed claims for naturopathic services in 200214. This is compared to National Health Statistics Reports (NHSR) population-based use estimates of 0.2% for naturopathic services in 2002 and 0.3% in 2007. The increase in use from 2002 to 2007 was, in part, attributed to the increase in naturopathic licensure during that time15. Although not a direct comparison, these findings suggest that licensing and credentialing NDs, as in Washington, increases the usage of naturopathic services.

Naturopathic profession

At the beginning of 2006, there were 4,010 licensed NDs in the U.S and Canada. This represents a 91% increase from 200116. Distance from naturopathic school and population density account for over 69% of the distribution of NDs, the same factors that predict the distribution of MDs17. NDs typically work in private practice, but are also employed by hospitals, clinics, community health centers, universities, and private industry1, 2. For NDs in private practice in Washington State, an estimated 78.9% reported sharing their office with other providers. These included other NDs (65.2%), acupuncturists (40.4%), massage therapists (40.4%), chiropractors (18.0%), MDs (13.7%), PhDs (6.8%), counselors (6.2%), registered nurses (5.0%), midwives (4.4%), and nutritionists (4.4%)18.

Within the licensed states of Washington and Connecticut, 75% of all visits to NDs were for chronic conditions, 20% were for acute conditions, and 5% were for wellness/preventive purposes. The most common complaints of patients seeking naturopathic care were fatigue, headache, musculoskeletal problems, anxiety/depression, menopausal symptoms, bowel and abdominal problems, allergies, and rash. The most common pediatric visits in Washington were for health supervision (27.4% of visits), infection (20.6% of visits), and mental health conditions (12.7% of visits). The majority of patients seen were middle-aged Caucasian women. Children were seen in 10.2% to 12.8% of visits, and individuals over the age of 65 were seen in 7.8% to 9.7% of visits19-21.

Over 70% of ND visits in Washington and Connecticut included physical examination or ordering laboratory/diagnostic tests. The most common examinations were vitals (28 to 39% of visits), HEENT (15 to 18% of visits), and complete physical (9 to 13% of visits). The most frequent laboratory tests were complete blood panels and serum chemistries, which were ordered in 7 to 10% of visits. Other labs were ordered less frequently and included thyroid panels, lipid panels, allergy tests, stool analyses, urine analyses, vitamin/mineral tests, endocrine, allergy skin tests, and TB skin tests. Diagnostic imaging including x-ray and ultrasound was ordered in 1 to 2% of visits. The most common treatments used were botanical medicine (43 to 51% of visits), vitamins (41 to 43% of visits), minerals (35 to 39% of visits), therapeutic diet (26 to 36% of visits), homeopathy (19 to 29% of visits), and self-care education (17 to 23% of visits). Modalities used less frequently included allergy treatment, acupuncture, glandular therapies, manipulation, exercise therapy, hydrotherapy, physiotherapy, mechanotherapy, ultrasound, and mental health counseling. Four percent of all visits included a referral to an MD, and 1 to 2% included a referral to another type of practitioner. The average visit lasted 40 minutes19. In pediatric visits in Washington, NDs administered immunizations during 18.6% of health supervision visits for children under the age of 2, and during 27.3% of visits for children aged from 2 to 5 years18.

Naturopathic Modalities

Diet and Clinical Nutrition

“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” Hippocrates. Proper nutrition is the foundation of a naturopathic practice, and food is utilized for both health promotion and disease prevention. NDs recommend diets individualized to each patient, though typically this means a balanced whole-foods diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole-grains, legumes, wild-caught fish, lean animal proteins, whole dairy products. In order to maximize nutritional value and minimize environmental impact, foods are considered best in their natural state, obtained locally, and eaten seasonally. NDs recognize how difficult and complex dietary changes may be, and assist patients through these changes by providing very specific individualized recommendations, as well as educational materials and resources.

There is overwhelming evidence that unhealthy eating habits significantly increase the risks for morbidity and mortality. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) determined that poor diet and physical inactivity caused 15.2% of all deaths in the U.S. in the year 2000, and may soon overtake tobacco as the leading cause of death22. It has been estimated that better nutrition could reduce the costs of heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes by an estimated $71 billion each year23. Obesity is also at an unprecedented high in the U.S. In 2009, the CDC reported that 66% of American adults, 17% of children ages 12-19, and 19% of children ages 6-11 years are overweight or obese24. The general dietary recommendations and follow-up strategies that NDs utilize with their patients could have a significant impact on both chronic disease and obesity. It has been well-established that diets high in fruits and vegetables are associated with decreased risk for chronic disease25. In addition, fruits and vegetables are generally low in calories thereby supporting healthy weight management26. NDs may also prescribe special diets such as the elimination diet, anti-inflammatory diet, and hypoallergenic diet. These diets have a long history of traditional use in naturopathic practice, but more research is needed in these areas to better determine clinical indications and efficacy. In one such study, the elimination diet was found to ameliorate clinical signs of inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and augment the beneficial effect of fish oil supplementation27.

The ultimate goal of naturopathic medicine is to optimize wellness by encouraging a healthy diet and lifestyle, but the ND may prescribe nutritional supplements if a specific deficiency is found or for certain conditions28. Studies have not only shown the benefits of nutritional supplementation in promoting health and preventing disease, but also the potential healthcare cost savings. One such study found the daily use of multivitamins containing folic acid and zinc by all women of childbearing age, and the daily use of vitamin E by those over the age of 50 could save nearly $20 billion annually in hospital charges related to heart disease, birth defects and low weight premature births29. There is much on-going research in the area of nutritional supplements at both conventional and naturopathic institutions30.

Behavioral Change

NDs emphasize that in order to live healthfully, one must work at it daily. Support is offered by the ND in the form of basic counseling, lifestyle modification, hypnotherapy, meditation, biofeedback, and stress management. NDs may also lead group classes in lifestyle modifications and stress management, helping foster community and connectedness for patients and physicians as they share and gain knowledge together. This holistic approach to healing acknowledges the importance of treating patients in the totality of their mind, body, and spirit environment. For the ND, it is essential to spend quality time listening to the patient in order to gain an understanding of how they live and strengthen the physician-patient relationship. There is overwhelming evidence that effective physician-patient communication is associated with improved patient health outcomes31 32.

A review of mindfulness research concluded that cultivating an enhanced mindful approach to living is associated with decreases in emotional distress, increases in positive states of mind, and an improvement in quality of life. Mindfulness practice was also found to positively influence the brain, the autonomic nervous system, stress hormones, the immune system, and health behaviors, including eating, sleeping, and substance use33. Additional information about mindfulness research is offered in another chapter of this volume.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy is the external or internal use of water in any of its forms (water, ice, steam) for health promotion or treatment of disease. It was used widely in ancient cultures, including Egypt, Persia, China, India, and Israel, before it was well established as the traditional European water cure34. Many of the treatments can be applied at home, making them cost effective and participatory for the patient.

Numerous studies have examined potential immunomodulatory effects of hydrotherapy treatments with promising results. A study testing the immune effects of cold water therapy in cancer patients found statistically significant increases in white blood cell counts including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, in subjects post-treatment compared with pre-treatment values35. In another study, repeated cold water stimulations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reduced the frequency of infections, increased lymphocyte counts, modulated interleukin expression, and improved subjective well-being36.

Numerous studies have also evaluated various hydrotherapy techniques for the treatment of specific conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, wound management, hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and chronic heart failure37-41. Hydrotherapy was generally found to be beneficial and safe for these conditions, but broad conclusions are not warranted due to sample size limitations and inconsistent methodologies. A meta-analysis of hydrotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome found moderate evidence that hydrotherapy has short-term beneficial effects on pain and health-related quality of life (HRQOL)42. A recent Cochrane Review on nasal saline irrigations for chronic rhinosinusitis found evidence the nasal lavage relieves symptoms, helps as an adjunct to treatment, and is well tolerated by most patients. There were no significant side-effects reported43. More research on hydrotherapy is indicated due to the promising preliminary findings in these areas.

Homeopathy

Homeopathy is a healing system that was created over 200 years ago by a German physician, Samuel Hahnemann. It is based on a central theory known as The Similia Principle. Substances made from plants, minerals or animals, which are known to cause symptoms similar to a certain disease, are given to patients in an extremely diluted form. Homeopathic remedies are believed to stimulate auto-regulatory and self-healing processes44. Remedies are selected by matching a patient's symptoms, based on taking a finely-detailed history, with symptoms produced by the substances in healthy individuals. Homeopathy is extensively used worldwide by homeopaths, MDs, DOs, NDs and DVMs. Across Europe, approximately a quarter of the population uses homeopathy, and depending upon the country, from 20% to 85% of all general practitioners either use homeopathy in their practices or refer their patients to homeopaths45.

There are over 200 clinical trials testing the efficacy of homeopathic treatments, many of which have led to positive results. However, an inconsistency in methods, limitations in sample sizes, as well as a lack of testing for single conditions, restricts pooling these results. A review evaluated the effectiveness of homeopathy in the fields of immunoallergology and common inflammatory diseases. Collectively, the evidence demonstrates that in some conditions homeopathy shows significant promise, e.g. Galphimia glauca for the treatment of allergic oculorhinitis. Classical individualized homeopathy showed potential for the treatment of otitis, fibromyalgia, and possibly upper respiratory tract infections and allergic complaints. A general weakness of the evidence is scarcity of independent confirmation of reported trials and conflicting results. The authors concluded that, considering homeopathic medicines are safe, they are a possible treatment option for upper airway infections, otitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma46.

Several other clinical trials on homeopathic medicines show promise as well. One trial evaluated homeopathic medicines for minimizing the adverse effects of cancer treatments, and found preliminary data in support of the efficacy of topical calendula ointment in the prevention of radiotherapy-induced dermatitis, and Traumeel S mouthwash for chemotherapy-induced stomatitis. The medicines did not cause any serious adverse effect or interact with conventional treatment 47. A Norwegian multi-center outcomes study found that 7 out of 10 patients visiting a homeopath reported a meaningful improvement in their main complaint 6 months after the initial consultation 48. Given these positive findings, as well as the rich history and wide-spread use of homeopathy, further research in this area is indicated.

Botanical Medicine

Traditional medicine has been used in communities for thousands of years. According to the World Health Organization, herbal treatments are the most popular form of traditional medicine 49. In developing countries, 80% of the population depends exclusively on medicinal plants for primary healthcare 50. NDs use herbal preparations in the form of teas, tinctures, poultices, balms, baths, elixirs, compresses, oils, syrups, suppositories, and capsules. The ND prescribes and prepares herbal remedies based on the uniqueness of each patient and their presenting symptoms. Organic and wild harvested herbs are used if available. A growing body of research supports the efficacy and safety of various herbs for preventing and treating many health conditions7.

A Cochrane review of herbal medicine for low-back pain found strong evidence that Harpagophytum procumbens (devil's claw) reduced pain better than placebo, and moderate evidence that Salix alba (white willow bark) and Capsicum frutescens (cayenne) reduced pain better than placebo in short-term trials. The authors also reported that the quality of reporting in these trials was generally poor, and that additional trials testing these herbal medicines against standard treatments are needed, particularly for long-term use51. In another Cochrane review, Crataegus laevigata (hawthorn leaf, flower and fruit) extract was found to provide a significant benefit in symptom control and physiologic outcomes as an adjunctive treatment for chronic heart failure. All 14 trials included in the review were double-blind, placebo controlled, RCTs52. A Cochrane review of Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) for the treatment of depression concluded that Hypericum perforatum extracts, a) are superior to placebo in patients with major depression; b) are similarly effective as standard antidepressants; and c) have fewer side effects than standard antidepressants. All studies included were double-blind, RCTs. However, the association of country of origin and precision with effects sizes complicated the interpretation53. The use of dietary supplements and primary care is explored further in another chapter of this volume.

Naturopathic Physical Medicine

Since the founding of naturopathy in the early twentieth century, physical medicine modalities have been an integral component of naturopathic treatments. Naturopathic physical medicine is the therapeutic use of physiotherapy, therapeutic exercise, massage, energy work, naturopathic manipulation, and hydrotherapy. It is distinct from the practice of chiropractic, physical therapy and physical rehabilitation7. Although it encompasses a broad range of treatment modalities, most are used for musculoskeletal conditions, such as injury and pain.

Research on naturopathic physical modalities is limited and results are inconsistent. A systematic review of low-intensity pulsed ultrasonography for the healing of fractures concluded that, although overall results are promising, the evidence is moderate to low in quality and provides conflicting results. The authors recommend large, blinded trials, directly addressing patient important outcomes, such as return to function54. A Cochrane review of therapeutic ultrasound for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome determined that no conclusion could be made due to poor reporting of the therapeutic application of the ultrasound and low methodological quality of the trials included55. A Cochrane review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain produced similarly questionable results. The authors reported that published literature on the subject lacks the methodological rigor needed to make confident assessments of the role of TENS in chronic pain management, and that large multi-centre RCTs of TENS are needed56.

Naturopathic Research

Much complementary and alternative (CAM) research to-date has focused on single modalities, specific supplements, and particular constituents of herbs. This type of research is taken out of context of the larger CAM medical system in which it is actually used57. The optimal research model used for evaluating naturopathic interventions must allow for individualized, multifaceted treatment strategies and potentially synergistic effects58. Whole systems research (WSR) is an emerging research paradigm, which may provide a better assessment of CAM therapies than classic RCTs, which attempt to determine the single best treatment for all patients. The goal of WSR is to evaluate treatments, products, specific modalities, and techniques within the context of the unique medical system in which they are used. Fundamental to WSR is developing appropriate study designs and analysis strategies for whole systems of medicine, recognizing the individuality of treatments and the participatory role of patients, emphasizing the healthcare environment and physician-patient interactions, including outcome measures based on patient-held values and individualized endpoints, and further developing a common understanding of the CAM models being studied. WSR is non-hierarchical, cyclical, adaptive, and holds qualitative and quantitative methods in equal esteem57, 58.

The Naturopathic Medical Research Agenda was an NCCAM-funded project spanning from 2002 to 2004, which developed recommendations for the direction and emphasis of naturopathic research through 2010. Participants included over 1200 individuals, representing a range of scientific and clinical backgrounds from leading naturopathic faculty to conventional physician scientists. Two priority populations were identified during these sessions, type 2 diabetes and elderly life-stage. For both of these populations, the goal is to compare naturopathic medical care to conventional care in large controlled trials. Specific approaches to naturopathic research were also identified, which include; 1) design and implement whole-practice research protocols focusing on naturopathic medicine as a primary care practice for both prioritized populations, 2) continue to research components of naturopathic medicine to include single agents for a specified diagnosis and mechanism of action studies, and 3) perform contextual research through observational studies, which study aspects of the practice of naturopathic medicine such as the patient-practitioner interaction and its integration with the larger medical system 59. Participating naturopathic medical schools are in the process of performing this research, and are in various stages of completion1, 60, 61.

There are a number of other current research projects, both federally and privately funded, at naturopathic medical schools in the U.S. and Canada. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) and The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) are substantial funding agencies for these projects. Examples of current research include a matched controlled outcomes study comparing integrated care to conventional care for the treatment of cancer (Bastyr University and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center), a pilot study evaluating the effects of magnet therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome (National College of Naturopathic Medicine), and a pragmatic randomized clinical trial of naturopathic medicine's ability to treat and prevent cardiovascular disease (Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine)1, 60, 61.

Integrative Patient Care

Goals of naturopathic medicine parallel those of family medicine in providing for and maintaining the well-being of both the patient and the healthcare system as a whole. Collaboration between conventional and naturopathic communities is growing as state licensing and insurance credentialing expands, and as the general public becomes more knowledgeable about CAM therapies62, 63. Patients are increasingly seeking out NDs for many reasons, including wanting a holistic approach that addresses the root of the problem, wanting more time and attention, having not been helped by conventional care, and having had a previous positive experience with an ND64 The conditions patients see licensed NDs for are many of the same conditions that they see conventional physicians for20. For those who choose integrative medicine, co-management of care and referral mechanisms will ensure optimally safe and effective patient care for several reasons. NDs are trained in potential drug/herb interactions and can provide educational support to patients and physicians. Naturopathic care may also reduce the need for some prescriptive drugs, and collaboration between the prescribing physician and the ND will be critical in determining medication dosing. NDs can also offer nutritional support around surgery and other procedures in order to reduce recovery time and potential complications. NDs are well-trained in identifying potentially life-threatening situations and medical conditions out of their scope of practice. Collaborative referral systems would provide continuity of care, comprehensive treatment, and optimal long-term patient management.

There are a number of integrative clinics nationwide that employ both NDs and MDs, and at least 20 hospitals that staff NDs. One such integrative clinic is Cedarburg Women's Health Center, located in Cedarburg, Wisconsin. The clinic was established by Janice Alexander, M.D. to provide primary care with prevention at the forefront. Michele Nickels, N.D. offers patients an integrative approach to health. The collaboration has been beneficial to both patients and physicians. Patients have seen that both types of medicine are needed for optimal health, and that each philosophy of medicine needs to be practiced by specialists. Dr. Alexander has experienced how knowledgeable NDs are regarding primary care, and has seen substantial results from naturopathic treatments in her patients. Dr. Nickels respects the expertise of Dr. Alexander, significantly benefiting from her mentorship, and discussion of patient cases has been mutually beneficial. Their patients agree that this type of medical care is at the forefront of primary care medicine.

Dr. Nickels also runs a private practice, Integrative Family Wellness Center, located in Brookfield, Wisconsin. The clinic offers conventional family medicine, as well as naturopathic medicine, chiropractic care, acupuncture, and manual therapy. Because of their holistic approach to healthcare and the additional time and attention provided to patients, the clinic has doubled in size in one year. Dr. Nickels emphasizes that patients want this type of primary care, and envisions healthcare moving in this direction as people become more educated and demand having a choice of treatment options (permission from Michele Nickels July 2009).

Another integrative clinic, located in Lokahi, Hawaii, is a partnership between Lokahi Health Center, the private practice Michael Traub, ND, and Pacifica Integrative Skin Wellness Institute, the dermatologic private practice of Monica Scheel, MD. There is much mutual referral between the two businesses. Dr. Traub's patients have access to the expertise of a board-certified dermatologist, and Dr. Scheel's patients have access to NDs who can address concerns that go beyond their dermatological conditions (permission from Michael Traub July 2009).

Resources

For more information, patients and physicians can go to the AANP at http://www.naturopathic.org/, the national association for licensed NDs. Additional local resources may be obtained from state naturopathic associations. The websites of accredited naturopathic medical schools (Table 2) provide information specific to naturopathic education. There are also a number of texts that offer information on the practice of naturopathic medicine and its related modalities (List 3).

Key Points

Naturopathic physicians (NDs) are trained as primary care physicians in 4-year accredited, doctoral-level naturopathic medical schools.

Currently, there are 15 U.S. states, 2 U.S. territories, and a number of provinces in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand that recognize licensure for NDs.

NDs are specialists in natural medicine and are trained in potential drug-herb interactions.

Treatment modalities utilized by NDs include diet and clinical nutrition, behavioral change, hydrotherapy, homeopathy, botanical medicine, physical medicine, pharmaceuticals, and minor surgery.

NDs work in private practice, hospitals, clinics, community health centers, universities, and private industry.

NDs often collaborate with conventional physicians in the co-management and mutual referral of patients.

An increasing number of insurance companies, unions, and state organizations are credentialing licensed NDs.

| Key Clinical Recommendation | Strength of Recommendation | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| The elimination diet improves clinical signs of inflammation in RA, and augments the beneficial effect of fish oil supplementation. | B | 27 |

| Daily use of multivitamins containing folic acid and zinc by women of childbearing age, and the daily use of vitamin E by those over the age of 50 reduces heart disease, birth defects and low weight premature births. | A | 29 |

| A “mindful” approach to living is associated with decreases in emotional distress, increases in positive states of mind, and an improvement in quality of life. | A | 33 |

| Cold water therapy increases white blood cell counts in cancer patients. | B | 35 |

| Cold water stimulations reduce frequency of infection, increase lymphocyte counts, modulate interleukin expression, and improve subjective well-being in COPD. | B | 36 |

| Hydrotherapy has short-term beneficial effects on pain and HRQOL in fibromyalgia syndrome. | A | 42 |

| Nasal irrigation for chronic rhinosinusitis relieves symptoms and augments standard treatment. | A | 43 |

| Classical individualized homeopathy shows potential for the treatment of otitis, fibromyalgia, and possibly upper respiratory tract infections and allergic complaints. | B | 46 |

| Topical calendula ointment minimizes the adverse effects of radiotherapy-induced dermatitis, and Traumeel S mouthwash minimizes the adverse effects of chemotherapy-induced stomatitis. | B | 47 |

| Harpagophytum procumbens (devil's claw), Salix alba (white willow bark) and Capsicum frutescens (cayenne) reduces low-back pain better than placebo. | B | 51 |

| Crataegus laevigata (hawthorn leaf, flower and fruit) extract provides benefit in symptom control and physiologic outcomes as an adjunctive treatment for chronic heart failure. | A | 52 |

| Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) extracts are superior to placebo and similar to antidepressants for major depression with fewer side effects. | A | 53 |

| Low-intensity pulsed ultrasonography may benefit the healing of fractures. | B | 54 |

| Therapeutic ultrasound may benefit patellofemoral pain syndrome. | C | 55 |

| TENS may aid in chronic pain management. | C | 56 |

| Collaboration between NDs and MDs has potential benefit for patients | C | 62, 63, practice of Nickels M 2009, practice of Traub M 2009 |

List 1: Principles of Naturopathic Medicine

The Healing Power of Nature (Vis Medicatrix Naturae) – Naturopathic medicine recognizes the body's natural healing ability, and trusts that the body has the innate wisdom and intelligence to heal itself if given the proper guidance and tools.

Identify and Treat the Causes (Tolle Causam) – NDs attempt to identify and treat the underlying cause of illness, rather than focusing on individual presenting symptoms.

First Do No Harm (Primum Non Nocere) – NDs begin with minimal interventions and proceed to higher level interventions only as determined necessary.

Doctor as Teacher (Docere) – NDs educate patients, involve them in the healing process, and emphasize the importance of the doctor-patient relationship.

Treat the Whole Person – Naturopathic medicine takes into account all aspects of an individual's health including physical, mental, emotional, genetic, environmental, social, and spiritual factors.

Prevention – Naturopathic medicine emphasizes optimal wellness and the prevention of disease.

Timeline of Pioneers in Naturopathic Medicine

List 2: Naturopathic Therapeutic Order

-

1Establish the conditions for health

- Identify and remove disturbing factors

- Institute a more healthful regimen

-

2

Stimulate the healing power of nature (vis medicatrix naturae): the self-healing processes

-

3Address weakened or damaged systems or organs

- Strengthen the immune system

- Decrease toxicity

- Normalize inflammatory function

- Optimize metabolic function

- Balance regulatory systems

- Enhance regeneration

- Harmonize life force

-

4

Correct structural integrity

-

5

Address pathology: Use specific natural substances, modalities, or interventions

-

6

Address pathology: Use specific pharmacologic or synthetic substances

-

7

Suppress or surgically remove pathology

From Zeff J., Snider P, Pizzorno JE. Section I: Philosophy of Natural Medicine. The Textbook of Natural Medicine 3rd ed. 2006;1(1), with permission.

List 3: Suggested Reading

Textbook of Naturopathic Medicine (2-volume set) Third Edition, Joseph E. Pizzorno Jr. N.D., Michael T. Murray N.D.

Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, Jeff M. Jellin, Pharm.D.

Woman's Encyclopedia of Natural Medicine, Tori Hudson, N.D.

An Encyclopedia of Natural Healing for Children and Infants, Mary Bove, N.D.

Plant Medicine in Practice: Using the Teachings of John Bastyr, Elsevier Science 2003, William Mitchell, N.D.

Herbal Medicine from the Heart of the Earth, Sharol Tilgner, N.D.

Feeding the Whole Family, Cynthia Lair.

Anti-Inflammation Diet and Recipe Book, Jessica Black, N.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bastyr University [June 29, 2009]; Available at: http://www.bastyr.edu/education/naturopath/degree/training.asp.

- 2.The American Association of Naturopathic Physicians [June 30, 2009]; Available at: http://www.naturopathic.org/content.asp?pl=16&contentid=16.

- 3.Kirchfeld F, Boyle W. Nature Doctors: Pioneers in Naturopathic Medicine. Medicina Biologica; Portland, Oregon: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeff J, Snider P, Pizzorno JE. The Textbook of Natural Medicine. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2006. Section I: Philosophy of Natural Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavaliere C. World news. Naturopathic profession growing rapidly in US and Canada. Herbalgram. 2007;(76):22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorman D, Kim L, Mittman P. Naturopathic medical education: Where conventional, complementary, and alternative medicine meet. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2002;7(2):99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaMont S, Quinn S, Donovan P, et al. Naturopathic medicine: Primary care for the 21st century. :1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges [June 29, 2009]; Available at: http://www.aanmc.org/.

- 9.Neall J, Hudson T. Naturopathic medicine residency programs. Altern Complement Ther. 2002;8(2):114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert DP, Butar FB. Diffusion of naturopathic state licensing in the United States and Canada. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2004;9(3):193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 11.North American Board of Naturopathic Examiners [June 30, 2009]; Available at: http://www.nabne.org/.

- 12.Washington Association of Naturopathic Physicians [June 30, 2009]; Available at: http://www.wanp.org/mc/page.do?sitePageId=58070&orgId=wanp.

- 13.Eisenberg DM, Cohen MH, Hrbek A, et al. Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(12):965–973. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Bellas AS, et al. Insurance coverage and subsequent utilization of complementary and alternative medicine providers. Am J Manage Care. 2006;12(7):397–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008;12:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albert DP, Martinez D. The supply of naturopathic physicians in the United States and Canada continues to increase. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2006;11(2):120–122. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albert DP, Butar FB. Distribution, concentration, and health care implications of naturopathic physicians in the United States. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2004;9(2):103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber W, Taylor JA, McCarty RL, et al. Frequency and characteristics of pediatric and adolescent visits in naturopathic medical practice. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e142–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boon HS, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al. Practice patterns of naturopathic physicians: Results from a random survey of licensed practitioners in two US states. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(6):463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber W, Newmark S. Complementary and alternative medical therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(6):983–1006. xii. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazao E. America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. Vol. 750. U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington, DC: 1999. High costs of poor eating patterns in the United States. pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [06/30, 2009]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/overwt.htm.

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture . Dietary guidelines for Americans. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2005. p. 34. Available from: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolls BJ, Ello-Martin JA, Tohill BC. What can intervention studies tell us about the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and weight management? Nutr Rev. 2004;62(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adam O, Beringer C, Kless T, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of a low arachidonic acid diet and fish oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23(1):27–36. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam J, Szmitko PE. Naturopathy: Complementary or rudimentary medicine? Univ of Toronto Med J. 2002;80(1):63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendich A, Mallick R, Leader S. Potential health economic benefits of vitamin supplementation. West J Med. 1997;166(5):306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) [July 19, 2009]; Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/research/extramural/awards/2008/.

- 31.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989:110–127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greeson JM. Mindfulness Research Update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2009;14(1):10. doi: 10.1177/1533210108329862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muir M. The healing power of water. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 1998;4(6):384–391. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuehn G. Potentiating Health and the Crisis of the Immune System: Integrative Approaches to the Prevention and Treatment of Modern Diseases. Plenum; New York: 1997. Sequential hydrotherapy improves the immune response of cancer patients. pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goedsche K, Forster M, Kroegel C, et al. Repeated cold water stimulations (hydrotherapy according to Kneipp) in patients with COPD. Forsch Komplementmed. 2007;14(3):158–166. doi: 10.1159/000101948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammond A. Rehabilitation in rheumatoid arthritis: A critical review. Musculoskeletal Care. 2004;2(3):135–151. doi: 10.1002/msc.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva LE, Valim V, Pessanha AP, et al. Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88(1):12–21. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCulloch J. Physical modalities in wound management: Ultrasound, vasopneumatic devices and hydrotherapy. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1995;41(5):30–2. 34, 36–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKay D. Hemorrhoids and varicose veins: A review of treatment options. Altern Med Rev. 2001;6(2):126–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michalsen A, Lüdtke R, Bühring M, et al. Thermal hydrotherapy improves quality of life and hemodynamic function in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2003;146(4):728–733. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langhorst J, Musial F, Klose P, et al. Efficacy of hydrotherapy in fibromyalgia syndrome--a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, et al. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2007;(3):CD006394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006394.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonas WB, Kaptchuk TJ, Linde K. A critical overview of homeopathy. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):393–399. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medhurst R. The use of homeopathy around the world. J Aust Traditional Med Soc. 2004;10:153. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellavite P, Chirumbolo S, Magnani P, et al. Effectiveness of homeopathy in immunology and inflammation disorders: A literature overview of clinical studies. Homeopath Heritage. 2008;33(3):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kassab S, Cummings M, Berkovitz S, et al. Homeopathic medicines for adverse effects of cancer treatments. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2009;(2):CD004845. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004845.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinsbekk A, Lüdtke R. Patients’ assessments of the effectiveness of homeopathic care in Norway: A prospective observational multicentre outcome study. Homeopathy. 2005;94(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO traditional medicine [06/09, 2009]; Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/.

- 50.Agra MF, Freitas PF, Barbosa-Filho JM. Synopsis of the plants known as medicinal and poisonous in northeast Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2007;17:114–140. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gagnier JJ, van Tulder MW, Berman B, et al. Herbal medicine for low back pain: A Cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(1):82–92. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000249525.70011.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pittler MH, Guo R, Ernst E. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005312. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005312.pub2. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L. St John's Wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000448. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Busse JW, Kaur J, Mollon B, et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for fractures: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brosseau L, Casimiro L, Robinson V, et al. Therapeutic ultrasound for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD003375. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003375. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nnoaham KE, Kumbang J. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD003222. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003222.pub2. 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritenbaugh C, Verhoef M, Fleishman S, et al. Whole systems research: A discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(4):32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verhoef MJ, Lewith G, Ritenbaugh C, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research: Beyond identification of inadequacies of the RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(3):206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Standish LJ, Calabrese C, Snider P. The Naturopathic Medical Research Agenda: The future and foundation of naturopathic medical science. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(3):341–345. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National College of Naturopathic Medicine: Helfgott Research Institute [July 6, 2009]; Available at: http://helfgott.org/projects.php.

- 61.Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine [July 6, 2009]; Available at: http://www.ccnm.edu/?q=current_research.

- 62.Dunne N, Benda W, Kim L, et al. Naturopathic medicine: What can patients expect? J Fam Pract. 2005;54(12):1067–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith MJ, Logan AC. Naturopathy. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(1):173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leung B, Verhoef M. Survey of parents on the use of naturopathic medicine in children--characteristics and reasons. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(2):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]