Abstract

Background

Most neonates less than 1.0 kg birth weight need red blood cell (RBC) transfusions. Delayed clamping of the umbilical cord 1 minute after delivery transfuses the neonate with autologous placental blood to expand blood volume and provide 60 percent more RBCs than after immediate clamping. This study compared hematologic and clinical effects of delayed versus immediate cord clamping.

Study Design and Methods

After parental consent, neonates not more than 36 weeks' gestation were randomly assigned to cord clamping immediately or at 1 minute after delivery. The primary endpoint was an increase in RBC volume/mass, per biotin labeling, after delayed clamping. Secondary endpoints were multiple clinical and laboratory comparisons over the first 28 days including Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology (SNAP).

Results

Problems with delayed clamping techniques prevented study of neonates of less than 30 weeks' gestation, and 105 neonates 30 to 36 weeks are reported. Circulating RBC volume/mass increased (p = 0.04) and weekly hematocrit (Hct) values were higher (p < 0.005) after delayed clamping. Higher Hct values did not lead to fewer RBC transfusions (p ≥ 0.70). Apgar scores after birth and daily SNAP scores were not significantly different (p ≥ 0.22). Requirements for mechanical ventilation with oxygen were similar. More (p = 0.03) neonates needed phototherapy after delayed clamping, but initial bilirubin levels and extent of phototherapy did not differ.

Conclusions

Although a 1-minute delay in cord clamping significantly increased RBC volume/mass and Hct, clinical benefits were modest. Clinically significant adverse effects were not detected. Consider a 1-minute delay in cord clamping to increase RBC volume/mass and RBC iron, for neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation, who do not need immediate resuscitation.

Multiple studies1-4 have demonstrated that delayed clamping of the umbilical cord at delivery, with consequent flow of autologous placental blood into the neonate, will provide up to 30 percent more blood volume and 60 percent more red blood cells (RBCs) to the neonate than after immediate cord clamping. For preterm neonates, several clinical trials of delayed versus immediate cord clamping have reported mixed results—sometimes favorable with improved circulatory hemodynamics, better cardiopulmonary adaptation to extrauterine life, diminished need for RBC transfusions, and less intraventricular hemorrhage after delayed cord clamping.1-4 For term infants, however, concerns have been raised that delayed clamping results in hypervolemia with respiratory distress, erythrocytosis with plethora and hyperviscosity, and hyperbilirubinemia. Thus, delayed cord clamping is not widely practiced in the United States because favorable clinical endpoints of delayed umbilical cord clamping trials have been inconsistent1-4 and because delayed cord clamping precludes prompt resuscitation of preterm neonates and may cause problems of “overtransfusion” in term infants.

One difficulty in drawing definitive conclusions about the physiology of delayed cord clamping and its application to clinical practice is the differences in clinical trial design that have led to imprecision in quantitating the increase in RBC volume/mass achieved by delayed umbilical cord clamping. Historically, “early” clamping was usually defined as occurring within 15 seconds of delivery and “late” as early as 1 minute after delivery.4 In actual practice, however, late clamping has varied among studies from 30 seconds to 5 minutes after delivery, with the volume of placental blood transfused into the neonate, likewise, varying as much as severalfold. Other factors that may influence the quantity of blood transfused from the placenta into the neonate include the position at which the delivered infant is held relative to the placenta in utero, the onset of breathing by the infant, and strength of uterine contractions with or without use of oxytocin.4

Because of these confounding factors, it is important to accurately quantitate the increase in neonatal RBC volume/mass after delayed umbilical cord clamping before ascribing the possible benefits and adverse findings—or lack thereof—to delayed clamping. The simplest method to attempt quantitation of the RBC volume/mass is by measuring the blood hematocrit (Hct) level after cord clamping. Unfortunately, the Hct level does not consistently reflect the true circulating RBC volume/mass during the first days of life—owing to changes in plasma volume that impact blood Hct results. For example, when studying a neonate in whom the RBC volume/mass is constant, a decreased plasma volume will concentrate circulating RBCs to give an increased blood Hct value that conveys a false impression of an increased RBC volume/mass, whereas an increased plasma volume will dilute RBCs to give a decreased Hct measurement and the false impression of a decreased RBC volume/mass.5,6

Because Hct values in preterm neonates may not accurately reflect the true effects of delayed cord clamping and placental transfusion on RBC volume/mass, we directly measured RBC volume/mass with autologous biotinylated RBCs in a cohort of preterm neonates entered into this randomized clinical trial of immediate versus delayed clamping of the umbilical cord.7 With a 1-minute delay of cord clamping after delivery, RBC volume/mass increased significantly (p = 0.04) compared to immediate clamping—establishing the effectiveness of delayed clamping of the umbilical cord. We now report several clinical and laboratory endpoints, assessed from birth through 28 days of life, resulting from this documented increase in RBC volume/mass.

Materials and Methods

Design of randomized clinical trial

A prospective, randomized, partially blinded (i.e., laboratory staff were unaware of group assignment) clinical trial was performed to evaluate the hypothesis that delayed clamping of the umbilical cord at delivery will increase neonatal circulating blood and RBC volumes and, further, that the increase will be sufficient to favorably influence several clinical and laboratory endpoints—including hemodynamic status and clinical condition, multiple laboratory studies, and need for RBC transfusions—without causing adverse effects of clinical importance. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Human Subjects Research Committee.

After informed consent was obtained from the parents, generally obtained as soon as the possibility of a preterm birth seemed likely and often well before labor and delivery, preterm neonates (≤36 weeks' gestation) were randomly assigned, by written instructions in sealed envelopes opened immediately before delivery, either to the standard institutional practice of immediate cord clamping (within 2-5 sec, but not to exceed 15 sec after delivery) or to a delayed clamping routine (described below) based on mode of delivery and gestational age. Separate sets of randomization envelopes were used for “large” neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation and for “small” neonates of less than 30 weeks, to ensure balance of variably sized neonates in the delayed and immediate cord clamping arms. Group assignment was generated with a table of random numbers. Because preterm infants differ substantially both biologically and clinically over the spectrum of viable gestational ages, neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation (large) and those less than 30 weeks' gestation (small) were managed differently, when assigned to delayed cord clamping. Although it became obvious, as the trial progressed, that neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation assigned to the delayed clamping group could not be studied successfully, it is important to describe the entire experimental design of this trial.

For large preterm neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation delivered vaginally and assigned to delayed cord clamping, the neonate was held in a receiving blanket 10 to 12 in. below the introitus with the placenta in utero, and the cord was clamped 3 to 5 cm from the neonate's abdomen exactly 60 seconds after delivery. The 60-second umbilical cord clamping coincided exactly with timing for the 1-minute Apgar score. For large neonates 30-36 weeks' gestation delivered by cesarean section (c-section), the neonate was placed beside the supine mother's thigh, and the cord was clamped as previously described at exactly 60 seconds after delivery with the placenta remaining in utero.

For all small preterm neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation, regardless of group assignment or mode of delivery, the cord was always clamped immediately after delivery to permit prompt resuscitation. For those assigned to the delayed clamping group, placental blood was then collected aseptically via needle puncture of the umbilical vein into sterile plastic bags containing citrate-phosphate-dextrose anticoagulant, while the placenta remained in utero. This placental blood was sent to the blood bank where it was centrifuged to pack the RBCs uniformly to a Hct level of approximately 85 percent (i.e., to prepare an identical RBC product, regardless of the quantity of placental blood collected). As soon as possible but always within the first 24 hours of life, 10 mL of RBCs per kg of infant birth weight was then transfused to mimic true delayed umbilical cord clamping.8 The rationale for transfusing 10 mL per kg RBCs, as a means to simulate true delayed cord clamping, is based on the estimated transfer of a mean of 20 mL per kg placental blood with a Hct level of approximately 50 percent during 60 seconds of delayed clamping.8

Biotinylated RBC measurement of RBC volume/mass

As reported previously in detail,7 autologous placental blood was collected at delivery. Within 24 hours after birth, these stored autologous RBCs were biotinylated and then were transfused into the infant at a dose of 1 mL per kg body weight. Dilution of the biotinylated RBCs was measured in a mixed venous or capillary sample obtained from the neonate 20 minutes after transfusion, and the circulating RBC volume/mass was calculated.

Clinical observations during the first 28 days of life

To assess neonatal clinical condition immediately after birth, Apgar scores were measured at 1 and 5 minutes after delivery, with a score of 10 indicating optimal status of heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, response to nasal catheter, and skin color.9 To assess overall neonatal clinical condition during the first week of life, the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology (SNAP) was used.10 In this system, a numerical score of 0 to 5 is assigned for each of 26 clinical and laboratory observations—including vital signs, blood gases, blood counts, serum bilirubin and electrolytes, renal function, stool guaiac, apnea and seizures, etc.—with a total score of 0 being perfect clinical condition and higher scores indicating increasing severity of illness. The clinical condition of neonates, quantitated by SNAP scores, was determined only for the first 8 days of life (i.e., Day 0 [day of birth] plus Days 1-7). In addition, because mechanical ventilation with oxygen was needed for longer than 8 days by some infants, details were recorded and analyzed separately for as long as this support was required. As another indication of clinical condition, somatic growth was assessed as body weight and length at birth and changes relative to birth on Days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Rates of intracranial hemorrhage and death were recorded.

The trial was also powered to detect a second primary endpoint, as a benefit of delayed umbilical cord clamping—a 50 percent decrease in the number of RBC transfusions given during the initial hospitalization. Transfusions were given uniformly as 15 mL per kg body weight, at the time of transfusion, of centrifuged RBCs that were from units stored up to 42 days. Indications for RBC transfusions were followed uniformly per written transfusion practice guidelines.11 Because a “single-donor program” had been in place for years, a reduction in donor exposures was not a testable endpoint.12 (As discussed in detail later, it became apparent during conduct of the trial that RBC transfusion reduction was not feasible as a primary endpoint.)

Laboratory observations during the first 28 days of life

The results of many laboratory studies were systematically tabulated, prospectively, per study design. SNAP scores were determined for the first 8 days of life. Serial Hct and platelet (PLT) counts were determined within 24 hours of birth, between 48 and 72 hours after birth, and on Days 7, 14, 21, and 28 of life. Serum bilirubin measurements were performed per discretion of the neonatologist, and all were recorded—as were the need for phototherapy, the duration of phototherapy, and the number of courses of phototherapy prescribed.

Overall nursery care

All neonates, regardless of the timing of umbilical cord clamping, were managed identically (i.e., respiratory and oxygen therapy, decisions for laboratory testing, fluid and nutritional management, use of antibiotics and other drugs, blood component transfusions). Phlebotomy blood losses were not measured. Recombinant human erythropoietin was not given.

Statistical analysis

By initial study design, there were two primary plus multiple secondary endpoints of the trial. The key primary endpoint was to document a significant increase in neonatal RBC volume/mass after delayed clamping of the umbilical cord compared to immediate clamping. To determine the number of infants to be studied, it was presumed that the circulating RBC volume/mass of preterm neonates after immediate cord clamping would be approximately 36 ± 4 mL per kg body weight8 and that the mean increase following delayed cord clamping should be 20 percent higher to be significant. With 10 neonates per group, the statistical test will detect this difference with 95 percent power at an alpha level of 0.05.

The second primary endpoint of the trial was to document a 50 percent decrease in RBC transfusions in the delayed umbilical cord clamping versus immediate clamping groups. All RBC transfusions were given uniformly as 15 mL per kg per transfusion according to written practice guidelines. At the time the trial began, each very-low-birth-weight, preterm infant at our center was known to receive a mean of 4.3 ± 2.8 RBC transfusions. It was estimated that a 50 percent decrease would result in 2.2 ± 1.4 transfusions per infant. With 25 neonates per group, the statistical test will detect this difference with 90 percent power at the 0.05 significance level.

To detect significant differences for the multiple secondary endpoints, the goal was to enroll enough infants to permit detection of at least a 25 percent difference in results between delayed and immediate cord clamping with 80 percent power at the 0.05 significance level. It was acknowledged that this could not be achieved for all secondary endpoints, but it was estimated that enrolling 88 infants into each of the delayed and immediate cord clamping arms could be achieved in a reasonable period of time and would be sufficient to detect some differences (e.g., blood Hct levels, need for mechanical ventilation, need for phototherapy).

Several statistical tests were used. For the single measurement outcome variables that were normally distributed, the two-sample t test was used. If the data distribution was not normal, either an appropriate transformation was applied to normalize the data or a non-parametric test, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, was used. The Pearson chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for comparing the categorical outcome variables between the two groups. For the outcome variables that were measured at multiple time points (i.e., PLT, Hct, weight, length), linear mixed model analysis for repeated measures was used. This included testing of group–time interaction. Pairwise group mean comparisons at each time point were performed with a test of mean contrast with p value adjusted with Bonferroni's method to account for the number of tests performed, corresponding to the number of time points. All the statistical analyses were performed with computer software (SAS, Version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Overview of randomized clinical trial

To adequately power for the two primary endpoints, a minimum of 25 neonates per each of the immediate and delayed umbilical cord clamping arms were enrolled successfully. To address as many of the secondary endpoints as possible, a total of 158 neonates were enrolled (86 in the immediate and 72 in the delayed cord clamping groups)—an imbalance that was unexpected. Per study design, the number of neonates studied in the immediate and delayed cord clamping groups should have been equal, but several neonates assigned to delayed umbilical cord clamping did not experience delayed clamping for various reasons and were lost from the trial. For example, whenever an unexpected complication of delivery occurred to place either the mother or the neonate at significant risk, the obstetrician was permitted to immediately clamp the umbilical cord—regardless of group assignment.

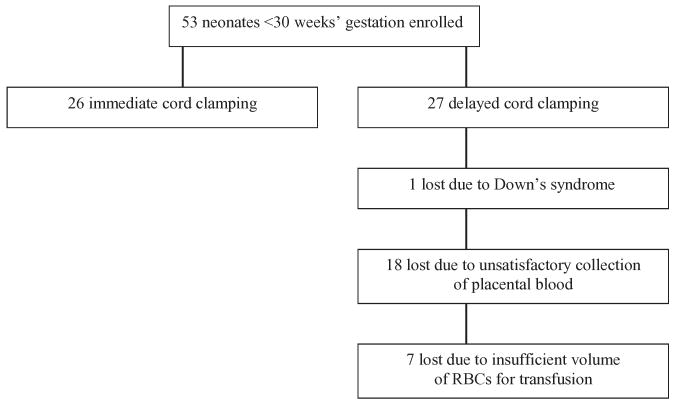

Of the 158 neonates enrolled, 105 were 30 to 36 weeks' gestation (60 immediate and 45 delayed clamping) and 53 were less than 30 weeks' gestation (26 immediate and 27 delayed clamping). A major loss of study subjects occurred because the plan to collect placental blood after immediate umbilical cord clamping of neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation, followed by transfusion within 24 hours to simulate delayed cord clamping, was unsuccessful (Fig. 1). Of 27 neonates enrolled in this arm, one was excluded shortly after birth due to Down's syndrome. In 18 of the remaining 26 neonates (69%), collection of autologous placental blood was unsatisfactory due to clotting of the umbilical vein before a sufficient volume of blood could be collected, gross hemolysis of the collected blood, contamination of placental blood with maternal blood (determined by Kleihauer-Betke stained blood smears), and volume of collected RBCs too small for processing in the blood bank. In the other 8 of the 26 neonates, in whom a transfusion of autologous placental RBCs was possible, the volumes were 7.0 to 10.1 mL per kg birth weight, with only one achieving the desired goal of 10 mL per kg. Because the neonates who failed simulated delayed cord clamping were identical to those in the immediate cord clamping group, there was no basis for comparison of delayed (n = 1) versus immediate (n = 26) clamping. Moreover, if included in the entire group comparison (i.e., “intention to treat”), the results could be biased to favor delayed clamping because that group would consist almost entirely of more mature, 30 to 36 weeks' gestation infants. Thus, data from study of the small neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation were not analyzed statistically and will not be reported.

Fig. 1.

Reasons 26 of 27 neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation assigned to delayed cord clamping were lost from the study. All 53 neonates experienced immediate cord clamping, with only 1 actually completing the entire delayed protocol. The imbalance of the final number of neonates successfully experiencing immediate or delayed clamping (26 immediate clamping vs. 1 delayed clamping) precluded meaningful comparisons.

Of neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation, 105 underwent an uncomplicated delivery and successfully experienced either immediate umbilical cord clamping (n = 60) or delayed cord clamping (n = 45). The number of neonates reported by the tables in the results section vary because some were discharged before 28 days of age and, occasionally, observations were not recorded (i.e., unsatisfactory laboratory sample).

Biotinylated RBC measurement of RBC volume/mass

As reported previously,7 this primary endpoint was achieved successfully. To recap, circulating RBC volume/mass, measured directly with autologous biotinylated RBCs within 24 hours after birth, increased significantly (p = 0.04) in neonates after delayed versus immediate umbilical cord clamping (42.1 ± 7.8 mL/kg vs. 36.8 ± 6.3 mL/kg). This difference was not reflected by concurrent blood Hct measurements (54.0 ± 4.7% in delayed clamping neonates vs. 53.6 ± 7.2% in immediate clamping neonates; p = 0.86).

Clinical observations

Apgar scores were nearly identical when neonates in the immediate and delayed and cord clamping groups were compared at 1 and 5 minutes after birth (Table 1). Neonatal clinical condition improved over time as evidenced by better scores at the 5-minute mark compared to 1 minute after birth. Similarly, there were no significant differences when SNAP scores, as a measure of critical illness, were compared daily for the first 8 days of life in neonates after immediate or delayed clamping of the umbilical cord (Table 2). On the day of delivery and for the following 2 days, the mean numerical SNAP scores were modestly higher in the immediate cord clamping group compared to the delayed group—suggesting the possibility of a slight, short-term benefit of delayed cord clamping.

TABLE 1. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes after birth (30-36 weeks' gestation)*.

| 1-minute score | 5-minute score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clamping time | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range |

| Immediate (n = 61) | 8.0 | 7.1 ± 1.8 | 0-10 | 9.0 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 4-10 |

| Delayed (n = 39) | 7.0 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 2-9 | 8.0 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 7-9 |

| p = 0.63 | p = 0.76 | |||||

The best score possible is 10.

TABLE 2. SNAP scores measured for 8 days: the first 24 hours (Day 0) and daily during Days 1 through 7 (30-36 weeks' gestation)*.

| Day 0 score | Day 1 score | Day 2 score | Day 3 score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clamping time | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range |

| Immediate (n = 60) | 4.0 | 5.5 ± 5.3 | 0-24 | 1.5 | 3.1 ± 4.6 | 0-19 | 2.1 ± 3.7 | 0-18 | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 3.0 | 0-16 | 1.0 |

| Delayed (n = 45) | 5.0 | 4.9 ± 3.7 | 0-17 | 1.0 | 2.2 ± 3.5 | 0-22 | 1.6 ± 2.6 | 0-12 | 1.0 | 1.8 ± 2.7 | 0-14 | 1.0 |

| p = 0.85 | p = 0.84 | p = 0.64 | p = 0.22 | |||||||||

| Day 4 score | Day 5 score | Day 6 score | Day 7 score | |||||||||

| Clamping time | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range |

| Immediate (n = 60) | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 0-11 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0-6 | 0.5 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0-7 | 1.0 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0-4 |

| Delayed (n = 45) | 1.0 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 0-7 | 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 0-6 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 0-7 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0-8 |

| p = 0.78 | p = 0.93 | p = 0.30 | p = 0.67 | |||||||||

The best score is 0, with increasing scores indicating increasing severity of illness.

Of all 105 neonates enrolled, only 10 (9.5%) needed mechanical ventilation. Although a higher percentage of neonates required mechanical ventilation after immediate umbilical cord clamping, this difference was not significant (p = 0.86), and they did not receive more days of ventilation or require higher concentrations of oxygen. Of neonates in the immediate cord clamping group, 12 percent (7 of 60) required mechanical ventilation for a mean of 3 days (median, 3 days), with a mean FiO2 of 32 percent (range, 21%-52%). After delayed cord clamping, 7 percent (3 of 45) of neonates required mechanical ventilation for a mean of 4 days (median, 3 days), with a mean FiO2 of 43 percent (range, 22%-63%).

None of the neonates died, and only two had Grade 1 intracranial hemorrhage—one in each of the immediate and delayed cord clamping groups. Weight and length at birth did not differ (p = 0.29 weight; p = 0.40 length) between neonates after immediate or delayed umbilical cord clamping; neither did changes in length (p = 0.73) when measured weekly during the first 28 days of life. Mean change in weight at 28 days, however, was significantly greater (p = 0.003) in immediate compared to delayed clamping infants (145% mean increase in immediate [95% confidence intervals (CIs), 140%-150%]; 132% mean increase in delayed [95% CIs, 126%-138%]). Results of repeated measures analysis agreed, as the growth profile over time differed significantly for weight (p = 0.04) but not length (p = 0.66).

Laboratory observations

Although blood Hct values measured within the first 24 hours of life, after either immediate or delayed clamping of the umbilical cord, were not significantly different—in agreement with our earlier report7 of data from only a small cohort of neonates—Hct values measured serially, at approximately 1-week intervals during the first 28 days of life, were significantly higher after delayed cord clamping (Table 3). Mean blood PLT counts measured at similar intervals did not differ significantly and were within the normal range of 150 × 109 to 400 × 109 per L (Table 3). The number of neonates given RBC transfusions and the number of transfusions needed by each transfused infant did not differ significantly between neonates experiencing immediate or delayed umbilical cord clamping (Table 4). As expected, a very small percentage of these larger infants between 30 and 36 weeks' gestation received RBC transfusions, and only one transfusion was given per transfused infant. Thus, the significantly lower blood Hct values in neonates in the immediate cord clamping group (Table 3) did not lead to clinical problems serious enough to warrant significantly more RBC transfusions (Table 4).

TABLE 3. Weekly blood Hct and PLT counts (mean ± SEM) during first 28 days of life (30-36 weeks' gestation)*.

| Day 0-1 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | Day 28 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clamping time | Hct | PLT† | Hct | PLT† | Hct | PLT† | Hct | PLT† | Hct | PLT† |

| Immediate (n = 55) | 53 ± 1.1 | 248 ± 17 | 47 ± 0.9 | 292 ± 28 | 41 ± 0.07 | 375 ± 33 | 36 ± 0.7 | 456 ± 36 | 31 ± 0.6 | 434 ± 37 |

| Delayed (n = 41) | 56 ± 1.3 | 241 ± 54 | 52 ± 1.0 | 334 ± 45 | 46 ± 0.8 | 365 ± 60 | 41 ± 0.9 | 401 ± 56 | 35 ± 0.8 | 469 ± 103 |

| p = 0.188 | p = 0.005 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||||||

Although most weekly blood counts were performed on Days 7, 14, 21, and 28 per study design, when counts were not performed on these exact days, blood samples obtained within 4 days before or after were accepted (e.g., for Day 7, counts obtained between Days 3 and 11 of life were accepted when an actual Day 7 count was not performed; counts between Days 11 and 17 for Day 14, etc.).

p Values for all PLT comparisons were greater than 0.99 to document no significant differences.

TABLE 4. Allogeneic RBC transfusions given during entire postpartum hospitalization (30-36 weeks' gestation).

| Total transfusions (15 mL/kg) given | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clamping time | Infants transfused | Total number given | Mean number per all infants | Mean number per transfused infants | Maximum number to any infant |

| Immediate (n = 59) | 5 (8%) | 5 | 0.08 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Delayed (n = 45) | 2 (4%) | 2 | 0.04 | 1.0 | 1 |

| p = 0.70 | |||||

Measurement of serum bilirubin and use of phototherapy were at the discretion of individual neonatologists, and most infants experienced phototherapy within the first days of life (Table 5). A significantly greater percentage of neonates needed phototherapy following delayed umbilical cord clamping versus immediate, but after serum bilirubin level at the start of phototherapy, the age at which phototherapy began, the duration of phototherapy, and the number of phototherapy courses needed did not differ between neonates experiencing immediate versus delayed umbilical cord clamping (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Serum bilirubin values (mg/dL) and use of phototherapy (30-36 weeks' gestation).

| Clamping time | Neonates needing phototherapy | Median/mean bilirubin at start of phototherapy* | Median (range) day of life phototherapy began* | Days of phototherapy* | Courses of phototherapy (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | One | Two or Three | ||||

| Immediate (n = 59) | 31 (53%) | 11/11 | 2 (1-5) | 3 | 1-7 | 90 | 10 |

| Delayed (n = 45) | 33 (73%) | 11/11 | 3 (1-7) | 3 | 2-7 | 81 | 19 |

| p = 0.03 | p = 0.38 | p = 0.39 | p = 0.38 | p = 0.30 | |||

Values per those infants given phototherapy.

Discussion

In a prospective, randomized, partially blinded, clinical trial of immediate versus delayed clamping of the umbilical cord in preterm neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation, we documented a significant increase in RBC volume/mass after delayed cord clamping.7 This finding supports a report by others in which neonatal whole blood volume was increased after delayed cord clamping (74.4 mL/kg) versus immediate clamping (62.7 mL/kg).13 This increase in RBC volume/mass was not reflected, immediately, by a significant increase in blood Hct values in neonates in the delayed umbilical cord clamping group,7 but it led to significantly higher Hct levels by Day 7 that persisted throughout the first 28 days of life. This documented increase in RBC volume/mass and blood Hct did not result in fewer RBC transfusions. The relatively large neonates (30-36 weeks' gestation at birth), however, required very few RBC transfusions—regardless of whether they were in the immediate or delayed cord clamping groups—precluding meaningful statistical comparison. Unfortunately, the smaller preterm infants (<30 weeks' gestation), who were predicted to need multiple RBC transfusions, were not reported because clinical and technical problems prevented those assigned to the delayed cord clamping group from receiving the planned autologous placental RBC transfusions that were intended to be equivalent to a true delay of umbilical cord clamping. These small infants deserve study because 76 percent of the 26 assigned to the immediate cord clamping group received transfusions (mean, 4.2 transfusions per infant; range, 1-19 transfusions per infant).

The significant increase in RBC volume/mass, seen with delayed umbilical cord clamping, had no measurable effect on Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes after birth—possibly because the time interval between cord clamping and Apgar scoring was too brief to permit expression of possible beneficial or adverse effects. As possible alternative explanations either the increase of RBC volume/mass (approx. 15%) after delayed umbilical cord clamping was too small to influence Apgar scores or an increase in RBC volume/mass after delayed clamping, even if of a greater magnitude, might not exert effects on the factors measured to calculate Apgar scores. The increases in RBC volume/mass and blood Hct, after delayed umbilical cord clamping, may have slightly improved the overall clinical condition of neonates briefly, as evidenced by lower (albeit, not significant) SNAP scores during the first few days of life. Although a slightly higher percentage of neonates in the immediate cord clamping group needed mechanical ventilation with oxygen, this difference was not significantly different—however, meaningful comparisons were impossible because relatively few neonates in either group needed this respiratory support.

The timing of umbilical cord clamping did not have a differential effect on the rate of intracranial hemorrhage. This is of particular interest because our findings do not support those of a previous report14 in which 36 percent of 36 neonates in the immediate umbilical cord clamping group had intraventricular hemorrhage versus 14 percent of 36 neonates whose cords were clamped after a 30- to 45-second delay after delivery. In the report by Mercer and colleagues,14 most neonates with intraventricular hemorrhage were less than 30 weeks' gestation, and those in the immediate cord clamping group were presumed to have a reduced cerebral blood volume. Notably in our study, neonates were at least 30 weeks' gestation, evaluation for intraventricular hemorrhage was performed at the discretion of the neonatologists, and the actual rate may have been underestimated. In agreement with our findings, however, Hofmeyr and colleagues15 did not show a significant decrease of intraventricular hemorrhage after delayed cord clamping.

There were no adverse effects of clinical importance apparent in our neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation after delayed umbilical cord clamping of 1-minute duration. Although mean Hct values were significantly higher after delayed cord clamping than immediate, the highest mean value was 56 percent—well below 65 percent, the value diagnostic for neonatal polycythemia.16 Moreover, no infant required phlebotomy for symptoms of polycythemia or hyperviscosity. Undoubtedly, this is due to the prematurity of our neonates—in contrast to the much higher Hct values that may occur after delayed cord clamping in term neonates.16,17 Although significantly more of our neonates received phototherapy for jaundice after delayed umbilical cord clamping, there were no differences in serum bilirubin values prompting this therapy or in the intensity of therapy required. This lack of relationship between delayed umbilical cord clamping and significant problems with polycythemia or jaundice in preterm neonates has been reported by others.14,18

It is important to note that our findings apply only to a 1-minute delay in umbilical cord clamping, whereas other studies assessed clamping delayed from 30 seconds to at least 3 minutes.2,3,8,13,14,17,18 Also, it must be remembered that our findings are based on neonates born between 30 and 36 weeks' gestation and therefore may not be generalized to all preterm neonates. In particular, we were unsuccessful in attempts to study smaller neonates less than 30 weeks' gestation for the multiple reasons described. Studies of delayed umbilical cord clamping in very immature neonates—the infants who might benefit most—will require methods by which true delayed cord clamping can be performed concurrently with resuscitation (e.g., neonate placed below the level of the placenta on a warming table, equipped with suction and oxygen). Alternatively, the method we attempted must be perfected (i.e., immediate umbilical cord clamping followed by collection and prompt transfusion of adequate quantities of good-quality autologous placental RBCs to simulate true delayed clamping). Meanwhile, it is reasonable to delay umbilical cord clamping for 1 minute in neonates 30 to 36 weeks' gestation, who do not require immediate resuscitation, because the increases in RBC volume/mass, blood Hct, and iron contained within the RBCs are likely to be of benefit.

Abbreviation

- SNAP

Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology

References

- 1.Yao AC, Lind J. Placental transfusion. Springfield (IL): Charles C. Thomas; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercer JS. Current best evidence: a review of the literature on umbilical cord clamping. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2001;46:402–14. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(01)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe H, Reynolds G, Diaz-Rossello J. Early versus delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub2. Art. No.: CD003248.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philip AG, Saigal S. When should we clamp the umbilical cord? NeoReviews. 2004;5:e142–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones JG, Holland BM, Hudson I, Wardrop CA. Total circulating red cell volume versus hematocrit as the primary descriptor of oxygen transport by the blood. Br J Haematol. 1990;76:288–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1990.tb07886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holland BM, Jones JG, Wardrop DA. Lessons from the anemia of prematurity. Pediatr Hematol. 1987;1:355–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss RG, Mock DM, Johnson K, Mock NI, Cress G, Knosp L, Lobas L, Schmidt RL. Circulating RBC volume, measured with biotinylated RBCs, is superior to the Hct to document the hematologic effects of delayed versus immediate umbilical cord clamping in preterm neonates. Transfusion. 2003;43:1168–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao AC, Moinian M, Lind J. Distribution of blood between infant and placenta after birth. Lancet. 1969;2:871–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anaesth Analg. 1953;32:260–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson DK, Gray JE, McCormick MC, Workman K, Goldman DA. Score for neonatal acute physiology: a physiologic severity index for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 1993;91:617–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss RG. Data-driven blood banking practices for neonatal RBC transfusions. Transfusion. 2000;40:1528–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40121528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss RG, Burmeister LF, Johnson K, James T, Miller J, Cordle DG, Bell EF, Ludwig GA. AS-1 red cells for neonatal transfusions—a randomized trial assessing donor exposure and safety. Transfusion. 1996;36:873–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.361097017172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aladangady N, McHugh S, Aitchison TC, Wardrop CA, Holland BM. Infants' blood volume in a controlled trial of placental transfusion at preterm delivery. Pediatrics. 2006;117:93–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer JS, Vohr BR, McGrath MM, Padbury JF, Wallach M, Oh W. Delayed cord clamping in very preterm infants reduces the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and late-onset sepsis: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1235–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmeyr GJ, Gobetz L, Bex PJ, Van der Griendt M, Nikodem C, Skapinker R, Delahunt T. Periventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage following early and delayed umbilical cord clamping: a randomized controlled trial. Online J Curr Clin Trials. 1993 Doc No 110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenkrantz TS. Polycythemia and hyperviscosity in the newborn. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:515–27. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceriani Cernadas JM, Carroli G, Pellegrini L, Otano L, Ferreira M, Ricci C, Casas O, Giordano D, Lardizabal J. The effect of timing of cord clamping on neonatal venous hematocrit values and clinical outcome at term: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;117:779–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ultee K, Swart J, van der Deure H, Lasham C, Van Baar A. Delayed cord clamping in preterm infants delivered at 34-36 weeks gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007 feb 16; doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.100354. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]