Abstract

Objective

Although not all findings are consistent, growing evidence suggests that individuals high in dispositional hostility are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality; however, the mechanisms of these associations remain unclear. One possibility is that hostility is associated with oxidative stress. Here, we explore relationships between hostility and a measure of systemic oxidative stress among a mid-life sample.

Methods

In a community sample of 223 adults aged 30–54 years (87% white, 49% female), oxidative stress was measured as the 24-hour urinary excretion of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). An abbreviated Cook Medley Hostility Scale was used to measure dimensions of hostility.

Results

Regression analyses controlling for demographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors showed a positive relationship of 8-OHdG with total hostility (β = .003, p = .03) and hostile affect (β = .018, p < .001).

Conclusions

These findings provide evidence that dispositional hostility, and in particular, hostile affect, covaries positively with systemic oxidative stress, raising the possibility that oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenicity of hostile attributes.

Keywords: Hostility, Hostile Affect, Oxidative Stress, 8-OHdG, DNA damage

Introduction

Hostility may be conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing attitudinal, affective, and expressive elements (1–3). Attitudinal and affective components of hostility are closely related and include attributions of hostile intent to others, attitudes of cynicism and mistrust, and the experience of angry affect. In contrast, the expressive dimension of hostility refers to overt aggressive behaviors or attitudes affording justification for such behaviors. Although not all findings are consistent (4–5), a substantial body of literature shows that hostility predicts risk for atherosclerosis, incident cardiovascular disease, and all cause mortality, particularly in younger populations (3,6–8). In general, effect sizes associated with hostility are comparable to lifestyle-related health risk factors such as smoking, exercise, and obesity (6–8), particularly when examining hard outcomes such as myocardial infarctions and coronary death (9). Although few studies have examined specific components of hostility, and findings are mixed, there is some evidence that the attitudinal and affective components of hostility are more strongly associated with adverse health outcomes than the behavioral components (3,8). To date, the pathophysiologic mechanisms linking hostility to disease remain unclear. Recent evidence raises the possibility that oxidative stress may comprise a potential pathway linking psychosocial characteristics to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, as well as other diseases of aging (10–13).

Oxidative stress is commonly defined as an imbalance between damaging pro-oxidants and protective antioxidants (14). Pro-oxidants, often termed reactive oxygen species (ROS) or free radicals, are clusters of atoms characterized by unpaired valence shell electrons, which can damage nearby proteins, lipids, and DNA. ROS are produced as part of normal cellular processes, but are generally neutralized quickly by antioxidants (15–17). However, any imbalance that results in a higher ratio of pro- to antioxidants can result in cellular damage. One widely-reported biomarker of oxidative stress, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), is a bi-product of repair to guanine bases of DNA (18). Systemic levels of 8-OHdG are thought to reflect cumulative oxidative damage to DNA throughout the body (19).

Oxidative stress is thought to contribute to disease risk through a number of physiologic pathways, including the promotion of inflammation, cellular proliferation, endothelial dysfunction, damage to DNA and proteins, and altered lipid metabolism (20–28). Furthermore, markers of oxidative DNA damage, such as 8-OHdG, are associated with cardiovascular risk (20,29), being elevated in patients with coronary artery disease (30–31), present in isolated atherosclerotic plaques (32), and positively related to intima-media thickness (33) and stage of atherosclerosis (32). Similarly, markers of lipid peroxidation are elevated in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and covary positively with cardiovascular risk factors (34). Preliminary prospective evidence also shows markers of oxidative stress to predict the progression of atherosclerosis (35–36) and coronary heart disease (37).

It is possible that oxidative stress provides a physiologic mechanism linking psychosocial factors to risk of atherosclerosis and all cause mortality. In this regard, clinical depression and psychological stress have been associated with elevations in markers of oxidative stress, including increased 8-OHdG (11), increased circulating levels of oxidized lipids (10,38), and decreased levels of antioxidants (12,38–40). Moreover, animal models show that chronic psychological stress promotes DNA damage and lipid oxidation (41–47). In addition, trait hostility, a suspected risk factor for atherosclerosis, incident cardiovascular disease, and all cause mortality has been related to decreased blood antioxidant levels (48) and elevated blood levels of DNA damage (49). The goal of the current study was to further examine associations of trait hostility with 8-OHdG among a community sample of mid-life volunteers. Because trait hostility has been associated with activation of the sympatho-adrenomedulary system (50,51), we also examined whether a measure of sympathetic arousal, urinary catecholamine excretion, explained a portion of any relationship between 8-OHdG and hostility.

Methods

Participants

Data for the present study were derived from the University of Pittsburgh Adult Health and Behavior (AHAB) project and were collected between January 2001 and May 2005. The AHAB project provides a registry of behavioral and biological measurements on non-Hispanic1 Caucasian and African American individuals (30–54 years of age) recruited via mass-mail solicitation from communities of southwestern Pennsylvania, USA (principally Allegheny County). Exclusion criteria for the AHAB project included a reported history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney or liver disease, cancer treatment in the preceding year, and major neurological disorders, schizophrenia or other psychotic illness. Other exclusions included pregnancy and the use of insulin, glucocorticoid, antiarrhythmic, psychotropic, or prescription weight-loss medications. A portion of AHAB participants (n = 306) were enrolled in a further data collection involving other instrumented biological assessments and a 24-hour urine collection (used in the present analyses). Additional exclusions for this component of AHAB participation included severe hypertension, heavy alcohol consumption (>21 drinks/week), extreme overweight (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40), and in women, current menstrual period irregularities. Data collection occurred over multiple laboratory sessions, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with approved protocol and guidelines of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Of the 306 AHAB participants who completed the 24-hour urine collection, 3 were removed from the analyses due to missing BMI data, no smoking history data, or a hostile attributions score that was identified as an outlier (> 3 SD above the mean). Measurement of 8-OHdG fell below the assay’s lower limit of detection (.5 ng/ml) for 80 individuals, leaving 223 subjects (49.8% female; 85.7% white) with continuous 8-OHdG data. Primary analyses are based on this latter sample, but non-parametric analyses on the full sample of 303 participants (50.5% female; 86.8% white) are also presented.

Procedure

Prior to beginning the urine collection, participants were asked to avoid vigorous exercise and heavy alcohol consumption for 24 hours. They were also asked to keep their urine sample refrigerated throughout the collection period. Urine samples were returned to the laboratory the day after collection, when urine volume was recorded and samples were frozen for later analysis. On a separate occasion, a project nurse administered a structured medical history and medication use interview and measured several standard risk factors, including blood pressure and BMI (kg/m2). Finally, participants completed a battery of psychosocial, lifestyle, and demographic questionnaires.

Hostility

Trait hostility was measured using a 39-item version of the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale (52), as derived by Barefoot and colleagues (1,52). This abbreviated Cook-Medley Scale (ACM) contains subscales tapping cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of hostility. Cognitive components of hostility include the tendency to view others with mistrust and to interpret their behavior as expressing an antagonistic intent directed at oneself (Hostile Attributions subscale), as well as a generally derogatory view of human nature in which selfish and deceitful motivations figure prominently (Cynicism subscale). Experiential elements of hostility measured by the ACM include the propensity to experience negative affect, particularly feelings of anger, irritability or impatience (Hostile Affect subscale) and to view confrontation and aggression as reasonable or legitimate forms of interpersonal behavior (Aggressive Responding subscale) (1). The ACM has good internal consistency (54) and a ten-year retest reliability of .74 (2). In addition, variants of the Cook-Medley scale have been shown to predict a variety of health-related outcomes, including all-cause mortality and incident cardiovascular disease, coronary artery atherosclerosis, variation in cardiac autonomic control, and common markers of immune function and systemic inflammation (e.g., 1–2,54–59).

Oxidative Damage

Urinary levels of 8-OHdG were determined using a commercially-available enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Oxis Corporation, California). This method has been demonstrated to be a reliable alternative to HPLC methods of determining 8-OHdG levels (19,60). Briefly, 50 μl of sample and standards were added to each well followed by 50 μl of 8-OHdG monoclonal antibody. The plate was mixed and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, washed, and then 100μl of secondary antibody was added. Following another hour of incubation at 37°C and a wash, 100μl of diluted Chromogen was added to each well and incubated for 15-minutes before a “stop” solution was added and the absorbance measured at 450nm. 8-OHdG values were extrapolated from a standard curve. All samples were run in duplicate and the average coefficient of variation between samples was 13.7%. The assay standard range is 0.05 to 200 ng/mL. To control for between-subject differences in general urine concentration, 8-OHdG levels were expressed as ng per mg of urinary creatinine. The later measurement was determined by standard protocol using the Beckman Creatinine Analyzer 2 (Beckman Coulter, Inc.; Fullerton, CA).

Urinary Catecholamines

Urinary levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine were determined using high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection. Interassay coefficients of variation for urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine were 2.2% and 3.7%, respectively. To control for between-subject variation in general urine concentration, epinephrine and norepinephrine levels (ng/ml) were expressed as ng per mg of urine creatinine.

Covariates

Empirical evidence shows associations of a number of demographic and lifestyle factors with self-reported hostility (61–62), oxidative damage (63–75), and cardiovascular risk (76–77). For example, male gender, African American race, lower socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), smoking, and blood pressure have been shown to covary positively with hostility (61–62) and cardiovascular risk (76–77), age and physical inactivity to covary with cardiovascular risk (76–77), and BMI, smoking, physical inactivity, and blood pressure to covary with oxidative damage (63–75). One or more of these factors might provide alternative explanations for associations between hostility and 8-OHdG. For this reason, demographic characteristics (sex, age, race, years of education, and family income), resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP), BMI, smoking status (entered as two nominal variables: current smoker vs. ex-smoker/never smoked and never smoked vs. current/ex-smoker), and physical activity (estimated kilocalories expended per week by the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire; 78) were selected as covariates.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 14.0). Prior to analyses, 8-OHdG values were reciprocally transformed and physical activity, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were log (base e) transformed to better approximate normal distributions. To test the primary hypothesis that hostility is associated with higher levels of urinary 8-OHdG, Pearson product-moment correlations were conducted. Secondary analyses were then performed to examine whether any associations between hostility and 8-OHdG were independent of the covariates. First, these analyses were conducted on participants with quantifiable levels of 8-OHdG (n = 223). Here, a series of regression analyses were conducted, entering covariates in the first step and hostility measures in the second step of models predicting 8-OHdG levels. Next, we conducted similar analyses on these 223 subjects along with the 80 individuals with urinary 8-OHdG values below the lower limit of detection of the assay. To accommodate these additional subjects in statistical analyses, we divided the sample based on the median 8-OHdG level creating two groups (Low 8-OHdG (n = 151): median = 1.57 ng/mg creatinine2, and High 8-OHdG (n = 152): median = 3.51 ng/mg creatinine). A series of logistic regression analyses was then performed examining whether hostility measures predicted 8-OHdG grouping independently of the covariates. For convenience, the signs of test statistics involving reciprocally transformed measurements of 8-OHdG are reversed, so that positive (and negative) coefficients are interpreted as such. To provide an estimate of the effect size of each association, we present the corresponding change in R squared with each F statistic.

Results

Associations between hostility and 8-OHdG

As expected, the total ACM hostility score was highly correlated with scores on the cognitive, affective, and behavioral subscales (See Table 1). Table 2 displays results of bivariate correlations between measures of hostility and urinary concentration of 8-OHdG. Consistent with the hypothesis, 8-OHdG covaried positively with the ACM Score, with stronger associations for the affective (hostile affect) subscale than for the cognitive (cynicism and hostile attributions) and behavioral (aggressive responding) subscales.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Total Hostility and Hostility Subscales on the abbreviated Cook-Medley (ACM) Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total Hostility | -- | .71** | .67** | .88** | .81** |

| 2. Hostile Affect | -- | .35** | .54** | .50** | |

| 3. Aggressive Responding | -- | .41** | .42** | ||

| 4. Cynicism | -- | .57** | |||

| 5. Hostile Attribution | -- |

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations between Hostility measured using the abbreviated Cook-Medley (ACM) Scale and 8-OHdG (ng/mg creatinine)

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) Hostility Score | r | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Hostility (Sum of subscales) | 14.5 (6.8) | .123 | .07 |

| Hostile Affect Subscale | 1.9 (1.3) | .206 | .002 |

| Aggressive Responding Subscale | 3.4 (1.9) | .058 | .39 |

| Cynicism Subscale | 5.9 (3.2) | .082 | .22 |

| Hostile Attributions Subscale | 3.3 (2.2) | .087 | .19 |

Associations between hostility and 8-OHdG after adjusting for covariates

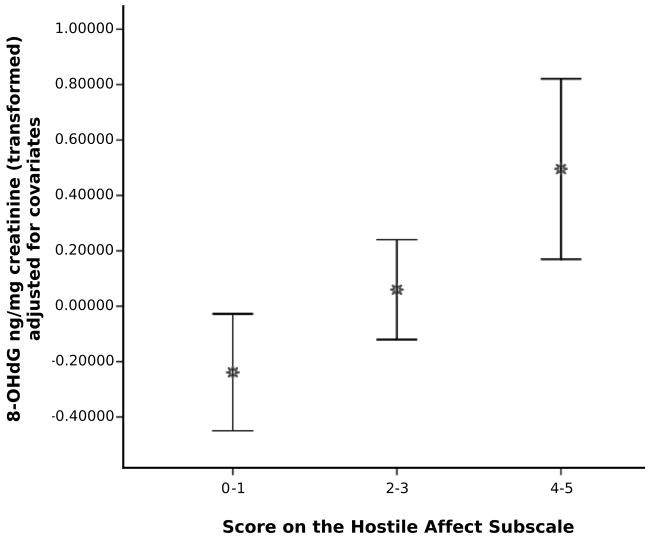

Next, we conducted analyses on the subsample of 223 participants with continuous data to examine whether demographic and health risk factors accounted for observed relationships between dispositional hostility and 8-OHdG (see Table 3). Of the covariates, non-white race (r = −.27, p < .001), fewer years of education (r = −.16, p = .02), lower family income (r = −.15, p = .03), and current smoking (r = .27, p < .001) were associated with higher ACM hostility. In contrast, none of the covariates were significantly associated with 8-OHdG. To determine whether the covariates accounted for associations between hostility measures and 8-OHdG, we next conducted a series of linear regression analyses. Consistent with bivariate analyses, separate regression analyses showed significant positive associations of 8-OHdG with total hostility scores (F(1, 210) = 4.69, p = .03) and the hostile affect subscale scores (F(1, 210) = 10.53, p < .001) after adjustment for covariates (see Figure 1). In contrast, there were no significant associations of scores on the aggressive responding, cynicism, or hostile attributions subscales with 8-OHdG after adjusting for covariates (see Table 4). There were no interactions of gender or race with any of the hostility measures in the prediction of 8-OHdG.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Mean 8-OHdG Values Across Demographic, Health and Lifestyle Factors

| Characteristics | Overall Means (SD) And % of Sample | Mean (SD) 8-OHdG ng/mg creatinine |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49.8% | 3.44(2.5) |

| Male | 50.2% | 3.20(2.8) |

| Agea | 44.3 (6.9) | |

| 30–40 | 31.8% | 3.22(1.7) |

| 41–50 | 43.1% | 3.53(3.6) |

| 51–60 | 25.1% | 3.09(1.5) |

| Race | ||

| White | 85.7% | 3.40(2.8) |

| Black | 13.0% | 2.74(1.4) |

| Other | 1.3% | 3.73(0.2) |

| Years of Educationa | 15.8 (2.6) | |

| 9–12 years | 13.5 % | 3.06(1.3) |

| 13–14 years | 21.9% | 3.13(1.2) |

| 15–16 years | 33.6% | 3.51(3.9) |

| 17 or more years | 30.9% | 3.36(2.3) |

| Family Annual Incomea | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 4.5% | 2.96(1.1) |

| $10,000–14,999 | 6.3% | 2.23(1.3) |

| $15,000–24,999 | 13.0% | 3.86(2.9) |

| $25,000–34,999 | 10.7% | 2.95(1.6) |

| $35,000–49,999 | 12.1% | 3.51(1.6) |

| $50,000–64,999 | 17.9 % | 3.75(4.2) |

| $65,000–80,000 | 13.0% | 3.35(3.6) |

| Greater than $80,000 | 22.4% | 3.11(1.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 26.4 (4.4) | |

| Underweight | .9% | .83(.13) |

| Normal | 39.0% | 3.22(1.9) |

| Overweight | 35.4% | 3.52(3.8) |

| Obese | 24.7% | 3.29(1.7) |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Current Smoker | 16.6% | 3.96(3.7) |

| Ex-Smoker | 25.6% | 3.67(3.7) |

| Never Smoked | 57.8% | 2.98(1.5) |

| Physical Activity (kilocalories)a | 2333(1688) | |

| Low (0–1354.3) | 33.2% | 3.05(1.4) |

| Moderate (1354.4–2531) | 33.2% | 3.56(3.0) |

| High (2532 +) | 33.6% | 3.36(3.2) |

| Systolic Blood Pressurea | 113.9 (.82) | |

| Below 140 | 95.0% | 3.34(2.7) |

| 140 and above | 5.0% | 2.99(2.2) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressurea | 73.2 (.60) | |

| Below 80 | 79.8% | 3.32(2.8) |

| 80 and Above | 20.2% | 3.34(1.8) |

These variables were categorized only for the purpose of display in this table. Continuous variables were used in all analyses when available. No statistically significant correlations of any of the demographic or lifestyle factors with 8-OHdG were found.

Figure 1.

Mean and 95% Confidence Interval of 8-OHdG ng/mg creatinine (transformed and adjusted for covariates) as a function of subjects’ scores on the hostile affect subscale of the ACM Hostility scale.

Table 4.

Results of regression analyses examining associations between hostility measured using the abbreviated Cook-Medley (ACM) scale and 8-OHdG after controlling for demographic characteristics and health covariates.

| Predictorb | β | CI | R2 change | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusting for Age & Gender | ||||

| Abbreviated Cook-Medley | ||||

| Total Hostility | .002 | .000–.004 | .017 | .049* |

| Subscales | ||||

| Hostile Affect | .018 | .007–.029 | .044 | .002** |

| Aggressive Responding | .004 | −.004–.012 | .004 | .35 |

| Cynicism | .003 | −.001–.008 | .008 | .18 |

| Hostile Attributions | .005 | −.002–.011 | .009 | .16 |

| Adjusting for all Covariatesa | ||||

| Abbreviated Cook-Medley | ||||

| Total Hostility | .003 | .000–.005 | .021 | .03* |

| Subscales | ||||

| Hostile Affect | .018 | .007–.03 | .045 | .001** |

| Aggressive Responding | .004 | −.004–.013 | .005 | .30 |

| Cynicism | .004 | −.001–.009 | .011 | .12 |

| Hostile Attributions | .005 | −.002–.012 | .009 | .15 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Covariates entered in this step of the regression equation: Age, gender, race, years of education, family income, smoking history, BMI, Physical Activity, SBP, and DBP.

Each hostility measure was entered in a separate model.

Levels of hostility among individuals in the high and low 8-OHdG groups

Next, we examined evidence for the same pattern of associations across the entire sample (n = 303). Initial t-tests and chi-square analyses showed no significant differences between the 8-OHdG groups on any of the demographic or health risk factors. Next, we used logistic regression analyses to examine whether our measures of hostility predicted 8-OHdG grouping after controlling for covariates. Consistent with the findings from the subsample with continuous 8-OHdG measures, hostile affect predicted 8-OHdG group (OR = 1.25, p = .02), with individuals who fell in the high 8-OHdG group reporting more hostile affect than those in the low 8-OHdG group, after controlling for covariates. There was also a trend for total hostility to predict 8-OHdG group (OR = 1.03, p = .14).

Catecholamines as a pathway linking hostility to 8-OHdG

To examine the possibility that activation of the sympathetic nervous system accounts for variance in 8-OHdG associated with hostility, we examined correlations of hostility and 8-OHdG with urinary concentrations of epinephrine and norepinephrine. Controlling for covariates, there were no significant associations between average 24-hour urinary epinephrine or norepinephrine and 8-OHdG (r = −.04, p = .58; r = −.03, p = .69, respectively) or hostility (r = −.06, p = .38; r = −.03, p = .63, respectively).

Discussion

This study provides further evidence for a positive association between trait hostility and urinary concentration of 8-OHdG, a marker of systemic oxidative burden, among relatively healthy midlife adults. Consistent with other studies demonstrating that psychosocial risk factors for CAD and all cause mortality are associated with oxidative stress (10–11,38–40,48–49), we found that individuals who describe themselves as higher in hostility excrete more 8-OHdG in urine than their less hostile counterparts. The positive association between trait hostility and 8-OHdG was independent of a number of demographic characteristics (age, race, gender, family income, and years of education) and other cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, BMI, smoking status, and physical activity). The present results parallel previous findings linking hostility to indicators of oxidative stress (48–49), raising the possibility that oxidative stress is a mechanism linking hostility to increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis and other diseases of aging.

Closer examination of the behavioral, affective and cognitive components of hostility revealed that the association between global hostility and 8-OHdG was largely attributable to hostile negative emotions, rather than hostile cognitions or behavioral tendencies. In this regard, hostile negative emotions are physiologically activating and associated with arousal of the sympathetic nervous system (51,79–80). Furthermore, catecholamines have been shown to act directly on cells to increase oxidative damage. For example, Okamoto et al. (81) observed increased DNA damage in cardiac myoblast cells after exposure to norepinephrine. More recently, Flint et al. (82) showed that incubation of precancerous cells with physiologically equivalent levels of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and cortisol resulted in increased DNA damage, an effect that was blocked by pretreatment with the corresponding antagonist.

To explore the possibility that hostile affect may contribute to oxidative damage via activation of the sympathetic nervous system, we examined levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine in the 24 hour urine samples used for the 8-OHdG assays. Inconsistent with the proposed pathway and previous findings (51,83), urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine levels were unrelated to hostility or 8-OHdG in the current sample. It is possible that if we had a more proximal measure of affective states taken at the time of the 24 hour urine collection, we would have found a significant association between negative affect and urinary catecholamines. In addition, the finding that levels of these catecholamines in a 24 hour urine collection are unrelated to oxidative damage does not rule out the possibility that the sympathetic nervous system is a biologic pathway of the oxidative damage that is associated with hostility. Indeed, much sympathetic activation takes place locally and is poorly reflected by the portion of neurotransmitters that escape reuptake and enter peripheral circulation to be excreted in urine. Furthermore, the magnitude of cellular responses to sympathetic activation is a function not just of the presence of catecholamines, but also of the density and sensitivity of receptors for the ligand (84–85). Thus, it remains possible that individuals who report higher levels of hostile affect show more activation of sympatho-adrenal pathways, resulting in greater oxidative damage.

Local activation of the sympathetic nervous system stimulates a number of biological effects that may directly or indirectly contribute to oxidative damage, including vascular damage resulting from sheer stress, platelet activation, and inflammation, as well as increases in blood glucose, lipid levels, and cellular metabolic activity (23,86–89). In particular, evidence shows that activated immune cells involved in the inflammatory response are a primary source of ROS (90–91). In this regard, growing evidence shows positive associations of systemic markers of inflammation and oxidative burden with risk for cardiovascular disease (35–37,92–93). It is likely that these two factors are not independent of one another, with evidence showing a positive association of inflammation and oxidative stress (94–96), and a recent clinical trial finding that antioxidant supplementation decreases systemic inflammation (97). Thus, further research is warranted to examine the role that the immune system plays in the oxidative stress that accompanies hostility.

In addition to physiologic mechanisms, it is possible that lifestyle factors contribute to associations between hostility and markers of oxidative stress. Inconsistent with existing literature linking smoking to markers of oxidative stress (e.g. 63), we found no association between urinary concentration of 8-OHdG and smoking status. These null findings may be the result of limited power with only 16.6% of the sample being current smokers, smoking between 1 and 80 cigarettes per day. Other studies have shown increased oxidative DNA damage among individuals with high blood pressure (64). However, blood pressure was not associated with 8-OHdG in the current sample, a finding that may reflect our systematic exclusion of individuals with hypertension from the sample. Although some prior studies have shown associations between lifestyle risk factors, such as BMI and sedentary lifestyle, and oxidative stress (65–67), not all findings are consistent (67–68) and there were no associations between these factors and 8-OHdG in the current sample. Finally, an inconsistent literature also points to associations between demographic factors and oxidative stress (69–75). In contrast to the findings of others (69–70,72–73,75), we observed no significant associations of race, gender, family income, or years of education with 8-OHdG in the current sample. Inconsistencies across studies may result from variability in sample characteristics, different measures of oxidative stress, and/or the reliability of the assessment methods. It is also possible that lifestyle variables not measured in the current study contribute to associations between hostility and oxidative damage. Here, diet is a likely candidate, with hostility being associated with increased intake of high fat food (98) and possibly with decreased consumption of antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables. In turn, diets low in antioxidants have been associated positively with oxidative stress (99) and damage to DNA (100). Thus, further investigation of the role of diet in explaining relationships between hostile affect and DNA damage is warranted.

There are a number of limitations of the current study that should be considered when interpreting findings. First, the cross-sectional design prevents us from making causal inferences regarding relationships between hostility and oxidative damage. Although unlikely, it is possible that oxidative stress results in an increase in hostility. Alternatively, hostility and DNA damage may be related to a third factor, such as genetic predisposition. Other limitations of the current study relate to the methods used to measure 8-OHdG and hostility. We employed a widely used measure of oxidative stress; however, concern has been raised regarding the specificity of the ELISA assay when compared with the more established HPLC methodology (19,101), making it difficult to compare absolute values across studies. The sensitivity range of the current assay also made it impossible to detect reliable levels of urinary 8-OHdG for the 80 individuals whose levels fell below the lower limit of detection. However, analyses that included these individuals in a low 8-OHdG group revealed a similar pattern of findings to the analyses run on the subgroup with quantifiable 8-OHdG, increasing confidence in the results. In addition, a comparison of individuals with and without detectable levels revealed no differences on demographic characteristics or any of the hostility dimensions. Another limitation of our study is the single assessment of 8-OHdG levels. Existing literature suggests that this measure is stable across time (102); however, a more reliable estimate of individual difference would be derived from multiple assessments. In regard to the measurement of hostility, we employed a widely used self report measure. However, it is possible that objective behavioral ratings or ratings provided by significant others provide a more reliable assessment of individual difference in hostility that may be more closely related to oxidative damage.

Despite the above shortcomings, the current findings provide interesting evidence that dispositional hostility, and particularly the affective component of this construct, is positively associated with a marker of systemic oxidative DNA damage among relatively healthy midlife adults. Given evidence that oxidative stress plays a role in the pathogenesis and progression of diseases of aging, these findings suggest a possible pathway linking hostility to increased morbidity and mortality. Future prospective research is warranted to investigate whether increased mid-life oxidative stress predicts future morbidity and provides a pathway linking hostility to disease risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants P01HL40962 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (SBM) and NR008237 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (ALM). The expert technical assistance of Emily MacLeod is gratefully acknowledged.

ACRONYMS

- 8-OHdG

8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine

- ACM

Abbreviated Cook-Medley Hostility scale

- AHAB

Adult Health and Behavior

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

Footnotes

The AHAB sampling frame excluded Caucasian participants of Hispanic origin due to their limited representation in the population sampled (communities of Southwestern PA) and to mitigate confounding by population stratification (substructure) in genetic analyses involving registry phenotypes.

Median in the low 8-OHdG group determined from the 71 subjects with quantifiable 8-OHdG values.

References

- 1.Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom G, Williams RB. The cook-medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buss AH. The psychology of aggression. New York: Wiley; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller TQ, Smith TW, Turner CW, Guijarro ML, Hallet AJ. A meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:322–348. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med. 2002;2:267–314. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, Hickie IB, Hunt D, Jelinek VM, Oldenburg BF, Peach HG, Ruth D, Tennant CC, Tonkin AM. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust. 2003;178(6):272–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: A critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:341–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:2192–2217. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myrtek M. Meta-analyses of prospective studies on coronary heart disease, type A personality, and hostility. Int J Cardiol. 2001;79:245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(01)00441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(49):17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forlenza MJ, Miller GE. Increased serum levels of 8-hydroxy-2′deoxyguanosine in clinical depression. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195780.37277.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hapuarachchi JR, Chalmers AH, Winefield AH, Blake-Mortimer JS. Changes in clinically relevant metabolites with psychological stress parameters. Behav Med. 2003;29:52–59. doi: 10.1080/08964280309596057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maes M, De Vos N, Pioli R, Demedts P, Wauters A, Neels H, Christophe A. Lower serum vitamin E concentrations in major depression. Another marker of lowered antioxidant defenses in that illness. J Affect Disord. 2000;58:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sies H. What is oxidative stress? In: Keaney JF, editor. Oxidative stress and vascular Disease. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 1999. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung HY, Jung KJ, Yu BP. Molecular inflammation as an underlying mechanism of aging: The anti-inflammatory action of calorie restriction. In: Surh Y, Packer L, editors. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and health. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. pp. 389–421. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaunig JE, Kamendulis LM. The role of oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:239–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu LL, Chiou CC, Chang PY, Wu JT. Urinary 8-OHdG: A marker of oxidative stress to DNA and a risk factor for cancer, atherosclerosis and diabetics. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;339:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths HR, Moller L, Bartosz G, Bast A, Bertoni-Freddari C, Collins A, Cooke S, Haenen G, Hoberg A, Loft S, Lunec J, Olinski R, Parry J, Pompella A, Poulsen H, Verhagen H, Astley SB. Biomarkers. Mol Aspects Med. 2002;23:101–208. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(02)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreassi MG, Botto N. Genetic instability, DNA damage and atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2003;3:224–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon MB, Libby P. Atherosclerosis. In: Sun B, editor. Pathophysiology of heart disease: a collaborative project of medical students and faculty. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griendling KK, FitzGerald GA. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular injury: Part 1: Basic mechanisms and in vivo monitoring of ROS. Circulation. 2003;108:1912–1916. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093660.86242.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keaney JF. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publisher; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loft S, Poulsen HE. Cancer risk and oxidative DNA damage in man. J Mol Med. 1996;74:297–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00207507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmoudi M, Mercer J, Bennett M. DNA damage and repair in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noguera A, Battle S, Miralles C, Iglesias J, Busquets X, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Enhanced neutrophil response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2001;56:432–7. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steptoe A, Brydon L. Psychoneuroimmunology and coronary heart disease. In: Vedhara K, Irwin M, editors. Human Psychoneuroimmunology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. The oxidative modification hypothesis of atherogenesis. In: Keaney JF, editor. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andreassi MG. Coronary atherosclerosis and somatic mutations: an overview of the contributive factors for oxidative DNA damage. Mutat Res. 2002;543:67–86. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botto N, Masetti S, Manfredi S, Petrzozzi L, Vassale C, Biagini A, Andreassi MG. Elevated levels of oxidative DNA damage in patients with coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2002;13:269–274. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demirbag R, Yilmaz R, Kocyigit A. Relationship between DNA damage, total antioxidant capacity and coronary artery disease. Mutat Res. 2005;570:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinet W, Knaapen MWM, De Meyer GRY, Herman AG, Kockx MM. Elevated levels of oxidative DNA damage and DNA repair enzymes in human atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2002;106:927–932. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000026393.47805.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gur M, Yilmaz R, Demirbag R, Yildiz A, Kocyigit A, Celik H, Cayli M, Polat M, Bas MM. Lymphocyte DNA damage is associated with increased aortic intima-media thickness. Mutat Res. 2007;617:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwedhelm E, Bartling A, Lenzen H, Tsikas D, Maas R, Brumer J, Gutzki FM, Chem I, Berger J, Frolich JC, Boger RH. Urinary 8-iso-prostaglandin F2-alpha as a risk marker in patients with coronary heart disease: A matched case-control study. Circulation. 2004;109:843–848. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116761.93647.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews B, Burnand K, Paganga G, Browse N, Rice-Evans C, Sommerville K, Leake D, Taub N. Oxidisability of low density lipoproteins in patients with carotid or femoral artery atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1995;112:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salonen JT, Yla-Herttuala S, Yamamoto R, Butler S, Korpela H, Salonen R, Nyyssonen K, Palinski W, Witztum JL. Autoantibody against oxidized LDL and progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992;339:883–888. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90926-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens JW, Gable DR, Hurel SJ, Miller GJ, Cooper JA, Humphries SE. Increased plasma markers of oxidative stress are associated with coronary heart disease in males with Diabetes Mellitus and with 10-year risk in a prospective sample of males. Clin Chem. 2006;52(3):446–452. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.060194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivonova M, Zitnanova I, Hlincikova L, Skodacek I, Trebaticka J, Durackova ZK. Oxidative stress in university students during examinations. Stress. 2004;7(3):183–188. doi: 10.1080/10253890400012685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khanzode SD, Dakhale GN, Khanzode SS, Saoji A, Palasodkar R. Oxidative damage and major depression: the potential antioxidant action of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Redox Rep. 2003;8(6):365–370. doi: 10.1179/135100003225003393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozcan ME, Gulec M, Ozerol E, Polat R, Akyol O. Antioxidant enzyme activities and oxidative stress in affective disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(2):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adachi S, Kawamura K, Takemoto K. Oxidative damage of nuclear DNA in liver of rats exposed to psychological stress. Cancer Res. 1993;53(18):4153–4155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischman HK, Pero RW, Kelly DD. Psychogenic stress induces chromosomal and DNA damage. Int J Neurosci. 1996;84(1–4):219–227. doi: 10.3109/00207459608987267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flint MS, Carroll JE, Jenkins FJ, Chambers WH, Han ML, Baum A. Genomic profiling of restraint stress-induced alterations in mouse T lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;167(1–2):34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barja de Quiroga G, Lopez-Torres M, Perez-Campo R, Abelenda M, Paz Nava M, Puerta ML. Effect of cold acclimation on GSH, antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in brown adipose tissue. Biochem J. 1991;277:289–92. doi: 10.1042/bj2770289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceremuzynski L, Barcikowski B, Lewicki Z, Wutzen J, Gordon-Majszak W, Famulski KS, et al. Stress-induced injury of pig myocardium is accompanied by increased lipid peroxidation and depletion of mitochondrial ATP. Exp Pathol. 1991;43(3–4):213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0232-1513(11)80120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das D, Bandyopadhyay D, Bhattacharjee M, Banerjee RK. Hydroxyl radical is the major causative factor in stress-induced gastric ulceration. Free Rad Bio Med. 1997;23:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davydov VV, Shvets VN. Lipid peroxidation in the heart of adult and old rats during immobilization stress. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36(7):1155–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohira T, Hozawa A, Iribarren C, Daviglus ML, Matthews KA, Gross MD, Jacobs DR. Longitudinal associations of serum carotenoids and tocopherols with hostility: The CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:42–50. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irie M, Asami S, Nagata S, Ikeda M, Miyata M, Kasai H. Psychosocial factors as a potential trigger of oxidative DNA damage in human leukocytes. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92(3):367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherwood A, Hughes JW, Kuhn C, Hinderliter AL. Hostility is related to blunted β-adrenergic receptor responsiveness among middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:507–513. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000132876.95620.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Jr, Zimmermann EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barefoot JC, Larsen S, von der Lieth L, Schroll M. Hostility, incidence of acute myocardial infarction, and mortality in a sample of older Danish men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:477–484. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and pharisaic-virtue scores for the MMPI. J Appl Psychol. 1954;38:414–418. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Contrada RJ, Jussim L. What does the Cook-Medley hostility scale measure? In search of an adequate measurement model. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1992;22:615–627. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC. Hostility as a predictor of survival in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):629–632. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138122.93942.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boyle SH, Jackson WG, Suarez EC. Hostility, anger, and depression predict increases in C3 over a 10-year period. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iribarren C, Sidney S, Bild DE, Liu K, Markovitz JH, Rosenman JM, Matthews K. Association of hostility with coronary artery calcification in young adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. JAMA. 2000;283:2546–2551. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marsland AL, Prather AA, Petersen KL, Cohen S, Manuck SB. Antagonistic characteristics are positively associated with inflammatory markers independently of traitnegative emotionality. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(5):753–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Shapiro PA, Kuhl JP, Chernikhova D, Berg J, Myers MM. Hostility, gender, and cardiac autonomic control. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:434–440. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cook MS, Lunec J, Evans MD. Progress in the analysis of urinary oxidative DNA damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1601–1614. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scherwitz LW, Perkins LL, Chesney MA, Hughes GH, Sidney S, Manolio TA. Hostility and health behaviors in young adults the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:136–45. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siegler IC. Hostility and risk: demographic and lifestyle variables. In: Siegman AW, Smith TW, editors. Anger, Hostility, and the Heart. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Negishi H, Ikeda K, Kuga S, Noguchi T, Kanda T, Njelekela M, Liu L, Miki T, Nara Y, Sato T, Mashala Y, Mtabaji J, Yamori Y. The relation of oxidative DNA damage to hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors in Tanzania. J Hypertens. 2001;19(3):529–533. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200103001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leeuwenburgh C, Heinecke JW. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in exercise. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:829–838. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mizoue T, Tokunaga S, Kasai H, Kawai K, Sato M, Kubo T. Body mass index and oxidative DNA damage: A longitudinal study. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1254–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pilger A, Ivancsits S, Germadnik D, Rudiger HW. Urinary excretion of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine measured by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 2002;778(1–2):393–401. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hofer T, Karlsson HL, Moller L. DNA oxidative damage and strand breaks in young healthy individuals: A gender difference and the role of life style factors. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:707–14. doi: 10.1080/10715760500525807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Basu S, Helmersson J, Jarosinska D, llsten GS, Mazzolai B, Barreg L. Regulatory factors of basal F2-isoprostane formation: Population, age, gender and smoking habits in humans. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10715760802610851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Block G, Dietrich M, Norkus EP, Morrow JD, Hudes M, Caan B, Packer L. Factors associated with oxidative stress in human populations. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:274–85. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giovannelli L, Saieva C, Masala G, Testa G, Salvini S, Pitozzi V, Riboli E, Dolara P, Palli D. Nutritional and lifestyle determinants of DNA oxidative damage: a study in a Mediterranean population. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1483–1489. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loft S, Vistisen K, Ewertz M, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Poulsen HE. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 1992 Dec;13(12):2241–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Proteggente AR, England TG, Rehman A, Rice-Evans CA, Halliwell B. Gender differences in steady-state levels of oxidative damage to DNA in healthy individuals. Free Radic Res. 2002;36(2):157–62. doi: 10.1080/10715760290006475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tarwadi K, Agte V. Linkages of antioxidant, micronutrient, and socioeconomic status with the degree of oxidative stress and lens opacity in Indian cataract patients. Nutrition. 2004;20:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylor AW, Bruno RS, Traber MG. Women and smokers have elevated urinary F(2)-isoprostane metabolites: a novel extraction and LC-MS methodology. Lipids. 2008;43(10):925–36. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Special Report: Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: A Review of the Literature. Circulation. 1993;88:1973–98. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paffenberger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schurmeyer TH, Wickings EJ. Principles of Endocrinology. In: Schedlowski M, Tewes U, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology: An interdisciplinary introduction. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pope MK, Smith TW. Cortisol excretion in high and low cynically hostile men. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:386–392. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okamoto T, Adachi K, Muraishi A, Seki Y, Hidaka T, Toshima H. Induction of DNA breaks in cardiac myoblast cells by norepinephrine. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;38:821–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flint MS, Baum A, Chambers WH, Jenkins FJ. Induction of DNA damage, alterations of DNA repair and transcriptional activation by stress hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J, Niaura R, Dyer JR, Shen B-J, Todaro JF, McCaffery JM, Spiro A, Ward KD. Hostility and Urine Norepinephrine interact to predict insulin resistance: The VA Normative Aging Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:718–726. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000228343.89466.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Norepinephrine and β2-Adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(4):487–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dong E, Yatani A, Mohan A, Liang C. Myocardial β-adrenoceptor down-regulation by norepinephrine is linked to reduced norepinephrine uptake activity. Euro J of Pharm. 1999;384(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Black PH, Garbutt LD. Stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Markovitz JH, Matthews KA. Platelets and coronary heart disease: potential psychophysiological mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:643–668. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meisenber G, Simmons WH. Principles of medical biochemistry. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rushmer RF. Structure and Function of the Cardiovascular System. In: Schneiderman N, Weiss SM, Kaufmann PG, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine. New York: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heinecke JW. Sources of vascular oxidative stress. In: Keaney JF, editor. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chung HY, Sung B, Jung KJ, Zou Y, Yu BP. The molecular inflammatory process in aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(3–4):572–581. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. The oxidative modification hypothesis of atherogenesis. In: Keaney JF, editor. Oxidative Stress and Vascular Disease. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kotur-Steveuljevic J, Memon L, Stefanovic A, Spasic S, Spasojevic-Kalimanovska V, Bogavac-Stanojevic N, Kalimanovska-Ostric D, Jelic-Ivanovic Z, Zunic G. Correlation of oxidative stress parameters and inflammatory markers in coronary artery disease patients. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dohi Y, Takase H, Sato K, Ueda R. Association among C-reactive protein, oxidative stress, and traditional risk factors in healthy Japanese subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:63–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abramson JL, Hooper WC, Jones DP, Ashfaq S, Rhodes SD, Weintraub WS, Harrison DG, Quyyumji AA, Vaccarino V. Association between novel oxidative stress markers and C-reactive protein among adults without clinical coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Devaraj S, Leonard S, Traber MG, Jialal I. Gamma-tocopherol supplementation alone and in combination with alpha-tocopherol alters biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Siegler IC, Costa PT, Brummett BH, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, Dahlstrom WG, Kaplan BH, Vitaliano PP, Nichaman MZ, Day RS, Rimer BK. Patterns of Change in Hostility from College to Midlife in the UNC Alumni Heart Study Predict High-Risk Status. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):738–745. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088583.25140.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cherubini A, Vigna GB, Zuliani G, Ruggiero C, Senin U, Fellin R. Role of antioxidants in atherosclerosis: Epidemiological and clinical update. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2017–2032. doi: 10.2174/1381612054065783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Freese R. Markers of oxidative DNA damage in human interventions with fruit and berries. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:143–147. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5401_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Peoples MC, Karnes HT. Recent developments in analytical methodology for 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine and related compounds. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;827(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miwa M, Matsumaru H, Akimoto Y, Naito S, Ochi H. Quantitative determination of urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine level in healthy Japanese volunteers. BioFactors. 2004;22(1–4):249–253. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520220150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]