Summary

We describe a new repressible binary expression system based on the regulatory genes from the Neurospora qa gene cluster. This ‘Q system’ offers attractive features for transgene expression in Drosophila and mammalian cells: low basal expression in the absence of the transcriptional activator QF, high QF-induced expression, and QF repression by its repressor QS. Additionally, feeding flies quinic acid can relieve QS repression. The Q system offers many applications including: 1) intersectional ‘logic gates’ with the GAL4 system for manipulating transgene expression patterns, 2) GAL4-independent MARCM analysis, 3) coupled MARCM analysis to independently visualize and genetically manipulate siblings from any cell division. We demonstrate the utility of the Q system in determining cell division patterns of a neuronal lineage and gene function in cell growth and proliferation, and in dissecting neurons responsible for olfactory attraction. The Q system can be expanded to other uses in Drosophila, and to any organism conducive to transgenesis.

Introduction

The ability to introduce engineered transgenes with regulated expression into organisms has revolutionized biology. A popular strategy for regulating expression of an effector transgene is to use a binary expression system. In this strategy, one transgene contains a specific promoter driving an exogenous transcription factor, while the other transgene uses the promoter activated only by that transcription factor to drive the effector gene. As a result, the effector gene is controlled exclusively by the chosen transcription factor, and the expression pattern of the effector transgene corresponds to the expression pattern of the exogenous transcription factor (Figure 1A). A number of binary expression systems have been established in genetic model organisms, including tetracycline-regulable tTA/TRE in mice (Gossen and Bujard, 1992) and GAL4/UAS in flies (Fischer et al., 1988; Brand and Perrimon, 1993). Compared to effector transgenes driven directly by a promoter, binary systems offer several advantages. First, binary systems usually result in higher levels of effector transgene expression due to transcription factor-mediated amplification. Second, expression of some effectors directly by a promoter may cause lethality and thus prevent the generation of viable transgenic animals; in binary systems, the effector transgene is not expressed until the exogenous transcription factor is introduced into the same animal, usually through a genetic cross. Third, some transcription factors used in binary systems can be additionally regulated by small molecule ligands and thus offer temporal control of transgene expression. Lastly, libraries of transgenes expressing a transcription factor and/or corresponding effectors can be established, such that the transcription factor and effector transgenes can be systematically combined by genetic crosses to enable expression of the same effector transgene in different patterns, or different effector transgenes in the same pattern, thereby enabling genetic screens in vivo.

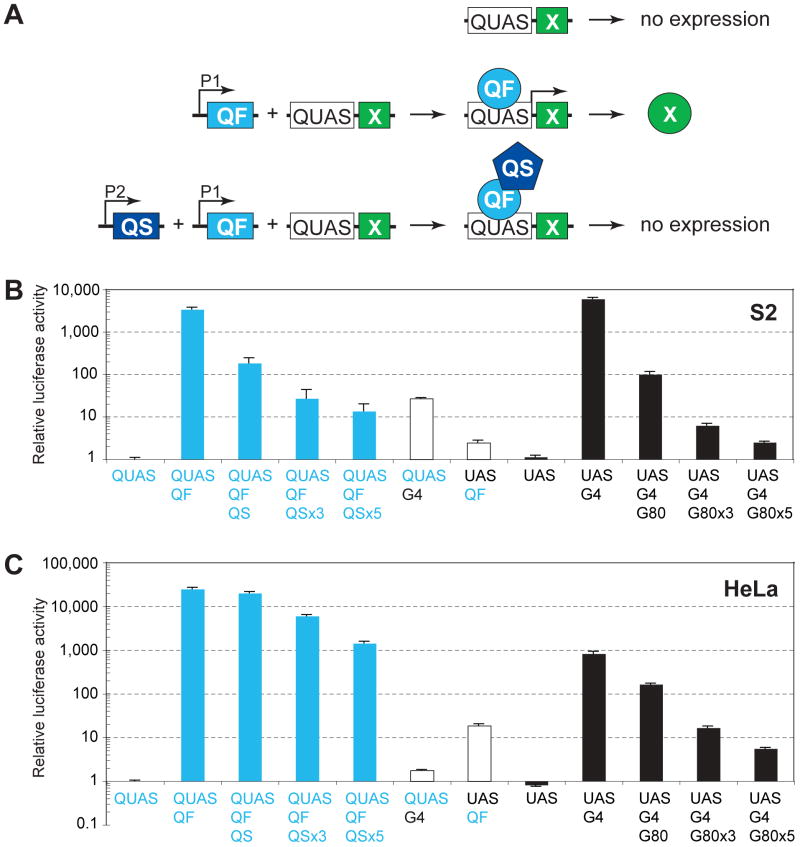

Figure 1. Characterization of the Q-system in Drosophila and Mammalian Cells.

(A) Schematic of the Q repressible binary expression system. In the absence of the transcription factor, QF, the QF-responsive transgene, QUAS-X, does not express X (top). When QF and QUAS-X transgenes are present in the same cell where QF is expressed (promoter P1 is active), QF binds to QUAS and activates expression of gene X (middle). When QS, QF and QUAS-X transgenes are present in the same cell, and both P1 and P2 promoters are active, QS represses QF and X is not expressed (bottom).

(B) Characterization of the Q-system in transiently transfected Drosophila S2 cells. Relative luciferase activity (normalized as described in Extended Experimental Procedures) is plotted on a logarithmic scale on the y-axis, with QUAS-luc2 alone set to 1. Error bars are SEM. Plasmids used for transfections are noted below the x-axis. QUAS, pQUAS-luc2 reporter; QF, pAC-QF; QS, pAC-QS; UAS, pUAS-luc2 reporter; G4, pAC-GAL4; G80, pAC-GAL80; ×3 and ×5, 3 and 5-fold molar excess of QS over QF or GAL80 over GAL4.

(C) Characterization of the Q-system in transiently transfected human HeLa cells. Explanations and abbreviations as in (B) except: QF, pCMV-QF; QS, pCMV-QS; G4, pCMV-GAL4; G80, pCMV-GAL80.

Figure S1 shows the effects of quinic acid on the Q and GAL4 systems.

The impact of the budding yeast-based GAL4/UAS binary expression system on studies of Drosophila biology cannot be overstated. Thousands of GAL4 lines have been characterized for expression in specific tissues and developmental stages (Brand and Perrimon, 1993; Hayashi et al., 2002; Pfeiffer et al., 2008). Tens of thousands of UAS-effector lines have also been established (Rorth et al., 1998), including a UAS-RNAi library against most predicted genes in the Drosophila genome (Dietzl et al., 2007). In addition to simple binary expression, the finding that the yeast repressor of GAL4, GAL80, efficiently represses GAL4-induced transgene expression in Drosophila (Lee and Luo, 1999) offered additional control of the system. For example, in combination with FLP/FRT–mediated mitotic recombination (Golic and Lindquist, 1989; Xu and Rubin, 1993), GAL80/GAL4/UAS can be used to create mosaic animals via MARCM (Mosaic Analysis with a Repressible Cell Marker) (Lee and Luo, 1999). Using MARCM, mosaic animals can be created that contain a small population of genetically defined cells labeled by a transgenic marker (such as GFP). At the same time, these labeled cells can be homozygous mutant for a gene of interest and/or modified with additional effector transgenes. The MARCM system has been widely used for lineage analysis, for tracing neural circuits, and for high-resolution mosaic analysis of gene function (Luo, 2007).

The versatile GAL4/UAS system still has limitations. The GAL4 expression patterns from enhancer trap lines or promoter-driven transgenes often include cells other than the cells of interest. It is thus difficult to assign the effect of transgene expression to a specific cell population, especially when phenotypes, such as behavior, are assayed at the whole organism level. Additionally, analysis of gene function and dissection of complex biological systems in multicellular organisms often requires independent genetic manipulations of separate populations of cells. To improve the precision of expression, intersectional expression methods such as the split GAL4 system (Luan et al., 2006) or the combined use of GAL4/UAS and FLP/FRT (Stockinger et al., 2005) have been introduced. To enable independent manipulation of separate populations of cells, additional binary systems such as the lexA/lexAO system have been developed (Lai and Lee, 2006). Here we describe a new repressible and small molecule-regulable binary expression system, the Q system, which offers significant advantages and versatility compared to the existing systems.

The Q system utilizes regulatory genes from the Neurospora crassa qa gene cluster. This cluster consists of 5 structural genes and two regulatory genes (QA-1F and QA-1S) used for the catabolism of quinic acid as a carbon source (Giles et al., 1991). QA-1F (shortened as QF hereafter) is a transcriptional activator that binds to a 16-base pair sequence present in one or more copies upstream of each qa gene (Patel et al., 1981; Baum et al., 1987). QA-1S (shortened as QS hereafter) is a repressor of QF that blocks its transactivation activity (Huiet and Giles, 1986) (Figure 1A). Here we explore the properties of the Q system in fly and mammalian cells, and demonstrate its utility for transgene expression, lineage tracing and genetic mosaic analysis in Drosophila in vivo.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the Q System in Drosophila and Mammalian Cells

To test whether qa cluster genes function in biological systems besides Neurospora, we created expression constructs for transient transfection of Drosophila and mammalian cells. We used the same ubiquitous promoters to drive QF and QS: actin 5c for Drosophila and CMV for mammalian cells. We generated a reporter plasmid containing the synthetic firefly luciferase (luc2) gene under the control of 5 copies of the QF binding site, which we termed QUAS, and the Drosophila hsp70 minimal promoter. We also created the GAL4-system equivalents as controls and for quantitative comparisons with the Q system.

Transfection of Drosophila S2 cells with QF and QUAS-luc2 resulted in ∼3,300-fold enhancement of luc2 expression compared with QUAS-luc2 alone (Figure 1B). For comparison, GAL4 induced luc2 expression from UAS-luc2 by ∼5,300-fold (Figure 1B) and therefore had ∼1.6-fold higher inducibility than QF/QUAS. GAL4/UAS also reached ∼1.8-fold higher absolute level of reporter expression than QF/QUAS. Co-transfection of QS with QF and QUAS-luc2 resulted in dosage-dependent suppression of luc2-expression (Figure 1B). Full suppression was not observed with equimolar ratios of QF and QS (similar lack of full suppression was observed with GAL4/GAL80). Quinic acid, which relieves suppression of QS in Neurospora (Giles et al., 1991), significantly suppressed QS to restore QF-based transcription (Figure S1A). Finally, QF and GAL4 showed minimal cross-activation of UAS and QUAS, respectively (Figure 1B, middle) — QF activation of UAS was ∼1,500 fold less than that of QUAS; GAL4 activation of QUAS was ∼200 fold less than that of UAS.

In human HeLa cells (Figure 1C), the Q system behaved similarly as in Drosophila S2 cells, but with the following distinctions. First, QF induced expression from QUAS by ∼24,000-fold, compared to ∼1000-fold induction of UAS by GAL4. Therefore, in human cells, QF/QUAS achieves ∼24-fold higher inducibility and ∼30-fold higher absolute level of reporter expression than GAL4/UAS. Second, higher QS:QF or GAL80:GAL4 molar ratios are required for effective suppression in HeLa cells compared with Drosophila S2 cells. Third, quinic acid does not suppress QS in mammalian cells, but seems to activate it further to make it an even better repressor (Figure S1B); the reasons for this unexpected behavior in mammalian cells are unknown. All these distinctions were also observed in COS cells (data not shown). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that the Q repressible binary expression system is effective in Drosophila and mammalian cells.

Repressible Binary Transgene Expression Using the Q System in Drosophila in vivo

To test whether the Q system functions in Drosophila in vivo, we generated transgenic flies that express: 1) different markers under the control of QUAS, 2) QF under the control of a specific promoter or in enhancer trap vectors, and 3) QS under the control of a ubiquitous tubulin promoter (tubP-QS) (Table S1).

Figure 2A-B (left panels) shows low basal fluorescence in whole mount Drosophila adult brains harboring only reporter transgenes, QUAS-mCD8-GFP (full length mouse CD8 followed by GFP) or QUAS-mtdT-HA (myristoylated and palmitoylated tandem repeat Tomato followed by 3 copies of the HA epitope). The low basal expression of QUAS and UAS reporters provides significant advantage compared to the lexA binary expression system (Lai and Lee, 2006).

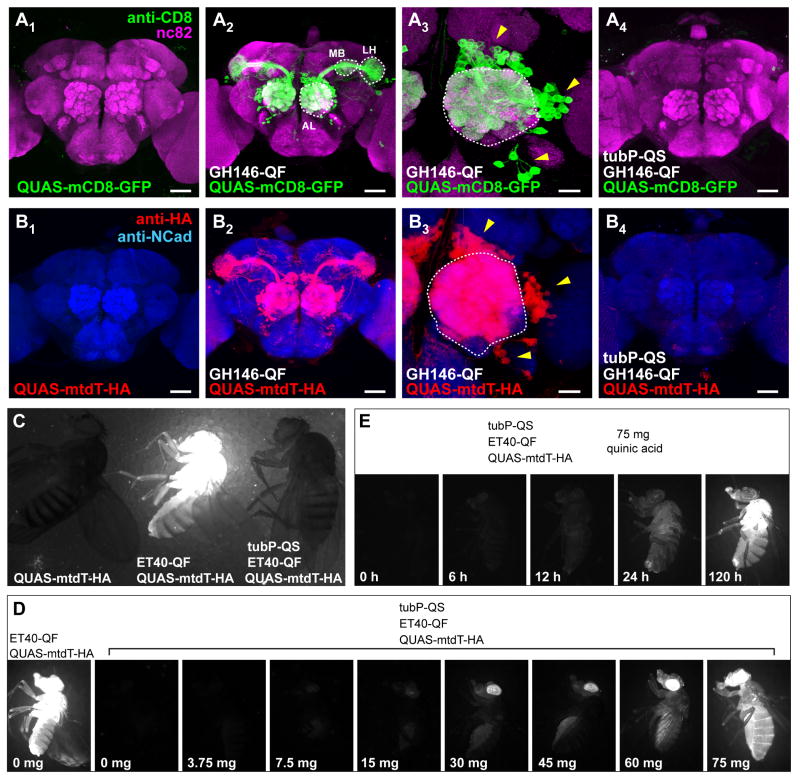

Figure 2. In Vivo Characterization of the Q system in Flies.

(A) Representative confocal projections of whole mount Drosophila brains immunostained for a general neuropil marker (monoclonal antibody nc82) in magenta, and for mCD8 in green. Genotypes are indicated at the bottom. A3 is a higher magnification image centered at the antennal lobe (AL; outlined). QF is driven by the GH146 enhancer that labels a large subset of olfactory projection neurons (PNs). PN cell bodies (arrowheads in A3) are located in anterodorsal, lateral or ventral clusters around the AL. PNs project dendrites into the AL, and axons to the mushroom body calyx (MB) and the lateral horn (LH) outlined. The green channel for A1 and A4 was imaged under the same gain, which is 15% higher than for the images shown in A2 and A3.

(B) Representative confocal projections of whole mount Drosophila brains immunostained for a general neuropil marker N-cadherin in blue, and for HA in red. The genotypes are indicated at the bottom. B3 is a higher magnification image centered at the AL (outlined). Arrowheads denote PN cell bodies. The red channel for B1 and B4 was imaged under the same gain, which is 15% higher than for the images shown in B2 and B3. The red staining in B4 is due to the DsRed transgenic marker associated with the GH146-QF transgene vector.

(C) Fluorescence images of three adult flies with genotypes as indicated.

(D) Fluorescence images of adult flies with genotypes indicated on top. Numbers on the bottom indicate the amount of quinic acid (dissolved in 300 μl of water) added to the surface of ∼10 ml fly food, on which these flies developed.

(E) Fluorescence images of adult flies showing time course of derepression of QS by quinic acid. The adult flies of the genotype listed on top were moved from vials with regular food to vials containing 75 mg quinic acid and imaged after the time interval shown on the bottom.

Scale bars: 50 μm for A1,2,4 and B1,2,4; 20 μm for A3 and B3.

Figure S2 characterizes additional QUAS reporters and QF enhancer trap lines.

All QUAS-mCD8GFP transgenic flies have basal reporter expression comparable to or lower than the lexO-mCD2-GFP line with the lowest reporter expression (Figure S2A). Low basal expression was also observed in other QUAS reporters such as QUAS-mdtT-HA (Figure S2A, data not shown). These observations suggest that the QUAS promoter is not easily influenced by genomic enhancers near the transgene insertion site and that flies do not contain endogenous proteins capable of inducing significant expression from QUAS-transgenes at least within the tissues we examined.

Introduction of QF expressing transgenes into flies containing QUAS-markers results in strong marker expression. For example, QF driven by the GH146 enhancer (Stocker et al., 1997; Berdnik et al., 2008) drives strong transgene expression in olfactory projection neurons (PNs; Figures 2A2-3 and 2B2-3). We also isolated enhancer trap lines that drive strong reporter expression in imaginal discs and adult tissues including large subsets of neurons and glia (Figure 2C, middle; Figure S2B-C). Expression of these transgenes was effectively suppressed by ubiquitous expression of QS (Figures 2A4, 2B4 and 2C, right; Figure S2B). These experiments show that the Q repressible binary system is as effective in vivo as the widely used GAL80/GAL4/UAS system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993; Lee and Luo, 1999).

The Q system provides an additional level of control compared to the GAL4 system: inhibition of QS by quinic acid. Adding increasing doses of quinic acid to fly food on which flies developed increasingly reverted the QS inhibition of enhancer trap ET40-QF driven QUAS-mtdT-HA expression (Figure 2D). When adult flies were transferred to quinic acid-containing food, reversion of suppression could be seen after 6 h, with marked reversion after 24 h and saturation by day 5 (Figure 2E, data not shown). Flies kept for 9 generations on food containing high doses of quinic acid, a natural product present at >1% in cranberry juice (Nollet, 2000), exhibited no noticeable abnormalities. Quinic acid can thus be used to temporally regulate QF-driven transgene expression. For instance, one can suppress developmental expression of a transgene and allow reactivation in adult for behavioral analysis, analogously to the GAL80ts strategy (McGuire et al., 2003). This manipulation can be achieved without changing the temperature, thereby avoiding complications with temperature-sensitive behaviors.

Q-MARCM

An incentive to develop the Q repressible binary system is the potential to build a new GAL4-independent MARCM system. The Q system-based MARCM (Q-MARCM) can then be used to mark and genetically manipulate a single cell or a small population of cells, while GAL4/UAS can be used to genetically manipulate a separate population of cells in the same animal. To test Q-MARCM, we placed tubP-QS distally to an FRT site and used FLP/FRT to induce mitotic recombination, so that one of the two daughter cells would lose tubP-QS, thus permitting QF to drive QUAS-marker expression (Figure 3A).

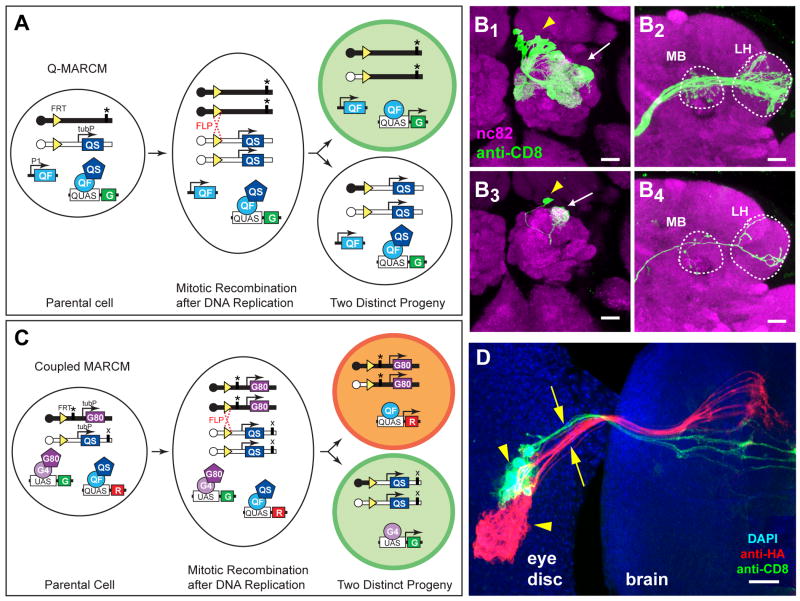

Figure 3. Q-MARCM and Coupled MARCM.

(A) Scheme for Q-MARCM. FLP/FRT mediated mitotic recombination in G2 phase of the cell cycle (dotted red cross) followed by chromosome segregation as shown causes the top progeny to lose both copies of tubP-QS, and thus becomes capable of expressing the GFP marker (G) activated by QF. It also becomes homozygous for the mutation (*). QF and QUAS reporter transgenes can be located on any other chromosome arm. P1, promoter 1. tubP, tubulin promoter. Centromeres are represented as circles on chromosome arms.

(B) Q-MARCM clones of olfactory PNs visualized by GH146-QF driven QUAS-mCD8-GFP. (B1-B2) Confocal images of an anterodorsal neuroblast clone showing cell bodies of PNs (arrowhead), their dendritic projections in the antennal lobe (arrows) and axonal projections in the MB and LH (outlined). (B3-B4) Confocal images of a single cell clone showing the cell body of a DL1 PN (arrowhead), its dendritic projection into the DL1 glomerulus (arrow) of the antennal lobe and its axonal projection in the MB and LH (outlined).

(C) Scheme for coupled MARCM. The tubP-GAL80 and tubP-QS transgenes are distal to the same FRT on homologous chromosomes. Mitotic recombination followed by specific chromosome segregation produces two distinct progeny devoid of QS or GAL80 transgenes, respectively, and therefore capable of expressing red (R) or green (G) fluorescent proteins, respectively. QF and GAL4 transgenes (not diagramed), as well as QUAS and UAS transgenes, can be located on any other chromosome arm. ‘*’ and ‘x’ designate two independent mutations that can be rendered homozygous in sister progeny.

(D) A coupled MARCM clone of photoreceptors, showing clusters of cell bodies (arrowheads) in the eye imaginal disc and their axonal projections (arrows) to the brain. The green clone was labeled by tubP-GAL4 driven UAS-mCD8-GFP; the red clone was labeled by ET40-QF driven QUAS-mtdT-HA. Blue, DAPI staining for nuclei. Image is a z-projection of a confocal stack.

Scale bars: 20 μm.

Figure S3 shows the lack of cross-activation and cross-repression of the Q and GAL4 systems in vivo, and a schematic of independent double MARCM.

Using GH146-QF to label olfactory PNs in Q-MARCM experiments, we found single cell and neuroblast clones labeled by QUAS-mCD8-GFP (Figure 3B) or QUAS-mtdT-HA (see below). In single cell clones, the dendritic innervation of individual glomeruli in the antennal lobe and stereotyped projections of single axons in the lateral horn appeared indistinguishable from previously characterized single cell clones labeled by GH146-GAL4-based MARCM (Jefferis et al., 2001; Marin et al., 2002; Jefferis et al., 2007). We have validated tubP-QS transgenes on all five major chromosome arms (Table S1), thereby allowing GAL4-independent MARCM analysis for a vast majority of Drosophila genes using the Q system.

GAL4 and QF showed minimal cross-activation of their respective upstream activating sequences in cultured cells (Figure 1B, C). Moreover, we could not detect any cross-activation (Figure S3A) or cross-repression (Figure S3B) of the GAL4 and QF systems in vivo. Therefore, QF- and GAL4-based MARCM (G-MARCM) can be combined in the same fly. If tubP-GAL80 and tubP-QS are placed distally to FRT sites on different chromosome arms (Figure S3C), independently generated clones can be labeled by Q- and G-MARCM. This arrangement, which we term ‘independent double MARCM’, can be used to study interactions between two separate populations of cells that have undergone independent mitotic recombination and genetic alteration. If tubP-GAL80 and tubP-QS transgenes are placed distally to the same FRT site in trans (Figure 3C), sister cells resulting from the same mitotic recombination can be labeled by Q- and G-MARCM respectively. We call the latter case ‘coupled MARCM’.

Figure 3D illustrates an example of coupled MARCM in the third instar larval eye disc. Sister cells and their descendants, derived from a single mitotic recombination event based on clone frequency and the proximity of labeled cells, are marked by tubP-GAL4 driven UAS-mCD8-GFP and ET40-QF driven QUAS-mtdT-HA. The photoreceptor cell bodies and their axonal projections into the brain were clearly visualized by both G-MARCM and Q-MARCM.

Analysis of Lineage and Cell Division Patterns using Coupled MARCM

The ability to label both progeny of a dividing cell with different colors via coupled MARCM (Figure 3C) can be used to characterize two important aspects of a developmental process: cell lineage and division patterns. As an example to illustrate such utility, we investigated the cell division pattern of a central nervous system neuroblast that gives rise to the adult olfactory PNs.

The cell division patterns of neuroblasts that generate adult insect CNS neurons are thought to follow the scheme shown in Figure 4A: a neuroblast undergoes asymmetric divisions to produce a new neuroblast and a ganglion mother cell (GMC), which divides once more to produce two postmitotic neurons (Nordlander and Edwards, 1969). A previous GAL4-based MARCM analysis of the mushroom body lineage supports this model: neuroblast, two-cell and single-cell clones can be produced (Figure 4B), and the frequency of the neuroblast and two-cell clones are roughly equal, reflecting the random segregation of the GAL80-containing chromosomes into the neuroblast or the GMC (Lee et al., 1999; Lee and Luo, 1999). However, when we analyzed PN lineages using MARCM and GH146-GAL4 (Jefferis et al., 2001) or GH146-QF (data not shown), we obtained either neuroblast or single cell clones, but no two-cell PN clones. Three different models can account for these data (Figure 4C). In model I, the stereotypical division pattern (Figure 4A) does not apply to this lineage: GH146-positive PNs are direct descendants of the neuroblasts. In models II and III, the general division pattern still applies, but the sibling for the GH146-positive PN is either a GH146-negative cell (model II), or it dies (model III).

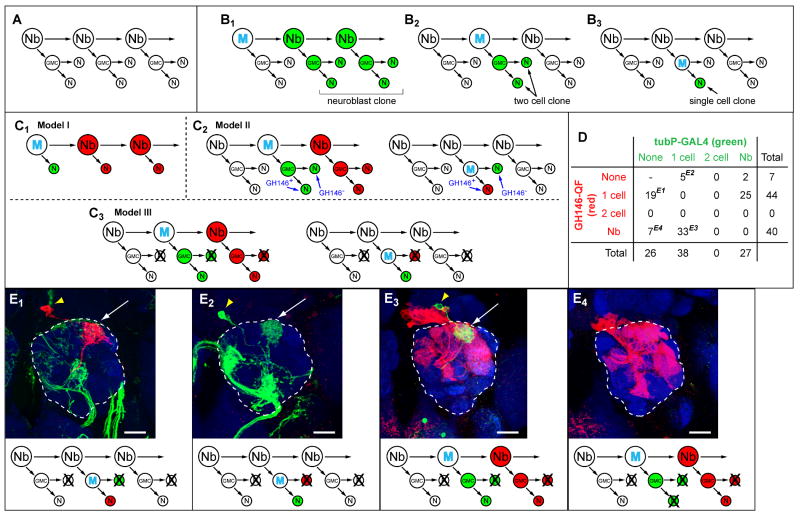

Figure 4. Lineage Analysis Using Coupled MARCM.

(A) General scheme for neuroblast division in the insect CNS. Nb, neuroblast; GMC, ganglion mother cell; N, postmitotic neuron.

(B) Three types of MARCM clones predicted from the general scheme. M, mitotic recombination.

(C) Three models to account for the lack of two cell clones in GH146-labeled MARCM. (C1) Each neuroblast division directly produces a postmitotic GH146-positive PN without a GMC intermediate. (C2) Each GMC division produces a GH146-positive PN and a GH146-negative cell. (C3) Each GMC division produces a GH146-positive PN and a sibling cell that dies. For models II and III, simulations of coupled MARCM results are shown for mitotic recombination that occurs either in the neuroblast or in the GMC.

(D) Tabulation of coupled MARCM results. Superscripts next to the numbers correspond to the images shown in (E) as examples.

(E) Examples of coupled MARCM that contradict models I and II, but can be accounted for by model III (bottom). (E1-E2) A single QF- (E1) or GAL4- (E2) labeled PN in the absence of labeled siblings. These events contradict model I (C1). In both examples, the additional green staining in the antennal lobe belongs to tubP-GAL4 labeled axons from olfactory receptor neurons. (E3) A single tubP-GAL4 labeled sibling (green) of a GH146-QF labeled neuroblast clone (red). This observation contradicts model II (C2). (E4) An occasional QF-labeled neuroblast clone with no tubP-GAL4 labeled siblings. All images are z-projections of confocal stacks; green, anti-CD8 staining for UAS-mCD8-GFP; red, anti-HA staining for QUAS-mtdT-HA; blue, neuropil markers. Arrowheads, PN cell bodies; arrows, dendritic innervation in the antennal lobe (outlined).

Scale bars: 20 μm.

See Figure S4 for a schematic for these coupled MARCM experiments.

We used coupled MARCM to distinguish among these models, focusing on the best-characterized anterodorsal lineage in which all progeny are PNs (Lai et al., 2008) and where birth order has been determined for most GH146-positive PNs (Jefferis et al., 2001; Marin et al., 2005). We used GH146-QF to label PNs derived from one progeny of a cell division, and the ubiquitous tubP-GAL4 to label the sibling progeny (Figure S4). We induced clones by heat-shock at different time windows within 0-100 h after egg laying and recovered a total of 91 coupled MARCM clones. We sorted the clones according to their labeling by GH146-QF and tubP-GAL4 (Figure 4D).

If model I were true, a single PN should always have a neuroblast sibling (Figure 4C1). However, we found 19 out of 44 single PNs labeled by GH146-QF without a tubP-GAL4 labeled neuroblast clone (Figure 4D; 4E1), and 5 out of 38 single PNs labeled by tubP-GAL4 without a GH146-QF labeled neuroblast clone (Figure 4D; 4E2). Thus, model I does not apply.

If model II were true, GH146-QF labeled neuroblast clones should be coupled with a two-cell clone labeled by the ubiquitous tubP-GAL4 (regardless of them being GH146-positive or GH146-negative; Figure 4C2 left). However, of the 40 GH146-QF labeled neuroblast clones, none of the tubP-GAL4 siblings were two-cell clones (Figure 4D). Instead, in 33 cases, the siblings were single cell clones (Figure 4E3), and in the other 7 cases, there were no labeled siblings (Figure 4E4). In addition, model II would predict pairs of sister cells each labeled by tubP-GAL4 or GH146-QF as a result of mitotic recombination in the GMC (Figure 4C2, right), but such an event was never observed (Figure 4D).

These experiments therefore support model III: the sibling of each PN dies during development and is no longer present in the adult brain (Figure 4C3). The frequent occurence of single singly-labeled PNs without labeled siblings could result from mitotic recombination in the GMC giving rise to two cells, one of which dies (bottoms of Figure 4E1, 4E2). In addition, occasionally both GMC-derived siblings may die, giving rise to neuroblast clones without any labeled siblings (Figure 4E4). This model is also supported by a recent study using different methods (Lin et al., 2010). It is possible that the division patterns producing PNs vary at different developmental stages and for different lineages. Future systematic studies using coupled MARCM can provide a comprehensive description of lineage and cell division patterns in these and other neuroblast lineages, and can create a developmental history for neurons of the adult Drosophila brain.

Comparisons with other methods

While this manuscript was in preparation, two other twin-spot labeling methods were reported. “Twin-spot MARCM” uses UAS-Inverse Repeat transgenes as repressors against two fluorescent proteins, and places these transgenes on the same chromosome arm in trans such that the FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination creates two sibling cells, each losing one of the RNAi repressor genes (Yu et al., 2009). “Twin-spot generator” (TSG), which is analogous to the MADM method in mice (Zong et al., 2005), places two chimeric fluorescent proteins on the same chromosome arm in trans. Upon FLP/FRT-mediated recombination, two fluorecent proteins are reconstituted and can be segregated to daughter cells (Griffin et al., 2009). The potential advantage of the TSG method is the ability to examine clones shortly after induction since there is no perdurance of a repressor; however, marker expression is low due to the lack of binary system-based amplification. In addition, both markers are driven by a ubiquitous promoter, thereby limiting the utility for tracking lineages in complex tissues such as the nervous system due to frequent interference by a large number of background mitotic clones. Twin-spot MARCM uses fewer transgenes than coupled MARCM. However, both progeny are labeled by the same GAL4 driver, thereby limiting the power for resolving cell division patterns (for example, siblings of a particular neuron may not be labeled by the same GAL4 line) and lacking the flexibility for selective manipulation of different siblings. Coupled MARCM offers robust marker expression and versatility as it can combine all available GAL4 and QF lines, whether cell-type-specific or ubiquitous. The combined use of ubiquitous tubP-GAL4 and PN-specific GH146-QF was key to resolving cell division patterns in the PN lineage, and it could not have been achieved using TSG or twin-spot MARCM. Furthermore, coupled MARCM can be used for independent gain- and loss-of-function genetic manipulations of both progeny. An example is illustrated in the next section.

Analyzing Cell Proliferation and Growth Using Coupled MARCM

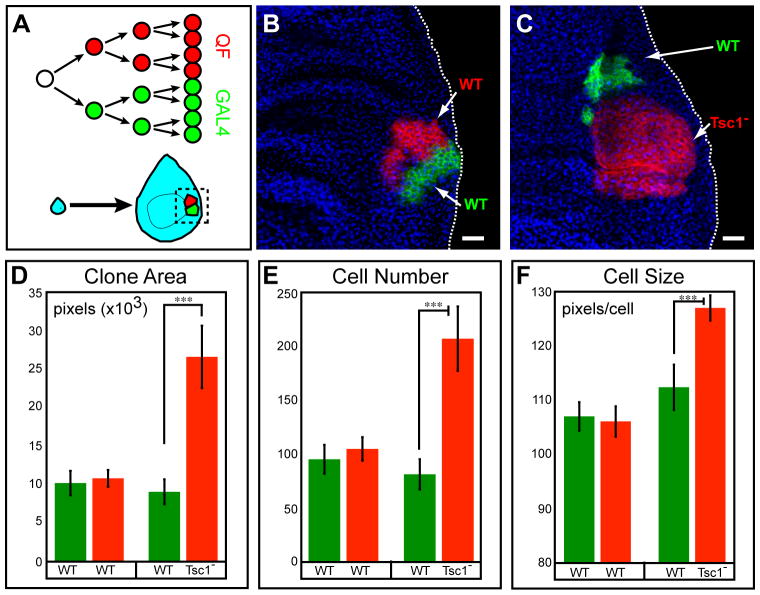

Coupled MARCM allows direct comparison of two cell populations that arise from a single cell division within the same animal. Here we illustrate its use to study cell proliferation and growth in the wing imaginal disc (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Coupled MARCM for Clonal Analysis of Mutant Phenotypes.

(A) Schematic for coupled MARCM labeling of dividing cells during imaginal disc development.

(B) A control coupled MARCM clone. Both GAL4- and QF-labeled siblings are wild type. Genotype: hsFLP, QUAS-mtdT-HA, UAS-mCD8-GFP (X); ET40-QF, QUAS-mtdT-HA/+ (II); tubP-GAL4, 82BFRT, tubP-GAL80/82BFRT,tubP-QS (III).

(C) A coupled MARCM clone where GAL4-labeled sibling (green) is wild type, while QF-labeled sibling (red) is homozygous mutant for Tsc1. Genotype: hsFLP, QUAS-mtdT-HA, UAS-mCD8-GFP (X); ET40-QF, QUAS-mtdT-HA/+ (II); tubP-GAL4, 82BFRT, tubP-GAL80, Tsc1Q600×/82BFRT, tubP-QS (III).

Green, anti-CD8; Red, anti-HA; Blue, anti-fibrillarin (labels nucleoli). Scale bars: 20 μm.

(D-F) Quantification of clone area, cell number and cell size for experiments in B and C. n=30 for WT vs. WT; n=21 for WT vs. Tsc1. Error bars are ± SEM. ***, p<0.001.

Figure S5 shows additional characterization of the effects of QF, GAL4, or QF+GAL4 expression on imaginal disc differentation.

The ∼50,000 epithelial cells of the wing disc are produced by exponential cell division from less than 40 progenitor cells during the larval stages of Drosophila development (Bryant and Simpson, 1984). Clonal analysis in the wing imaginal disc is a sensitive strategy for studying the effects of genetic perturbations on cell growth or proliferation. To verify that QF expression does not affect normal cell growth or proliferation, we used coupled MARCM to label wild-type clones in the larval wing imaginal disc (Figure 5B). Clones were induced by heat-shock at 48 h after egg laying, and examined 72 h later. The area of the GAL4- and QF-labeled clones, their cell number and cell size (Figures 5D, 5E and 5F, respectively) were indistinguishable from one another. These results indicate that G-MARCM and Q-MARCM do not differentially affect cell proliferation or growth of wing disc cells. Additional control experiments indicated that high levels of QF expression did not interfere with growth and patterning of imaginal discs and the corresponding adult structures (Figure S5).

To show the utility of coupled MARCM in mutant analysis, we generated wing imaginal disc clones in which control cells were labeled by GAL4 and Tuberous Sclerosis 1 (Tsc1) homozygous mutant cells were labeled by QF. Tsc1, along with its partner Tuberous Sclerosis 2 (Tsc2), forms a complex that negatively regulates the Tor pathway to affect both cell size and cell proliferation (Ito and Rubin, 1999; Potter et al., 2001; Tapon et al., 2001). We found that Tsc1 mutant clones (labeled red via QF) were significantly larger than wild-type clones (labeled green via GAL4) (Figure 5C), covering on average 2.9-fold larger area than their control sister clones (Figure 5D). To determine if the increase in clone area is due to an increase in cell proliferation or cell size, we counted the number of cells within these labeled clones. We found a two-fold increase in cell numbers in Tsc1 mutant clones compared to the sister clones, yet only a 26% increase in cell size (Figure 5E-F), suggesting that mutation of Tsc1 in rapidly dividing cells primarily leads to an increase in proliferative capacity. This example, although largely confirmatory of previous findings, illustrates the utility of coupled MARCM for investigating gene function in developmental processes.

Refining Transgene Expression by Intersecting GAL4 and QF Expression Patterns

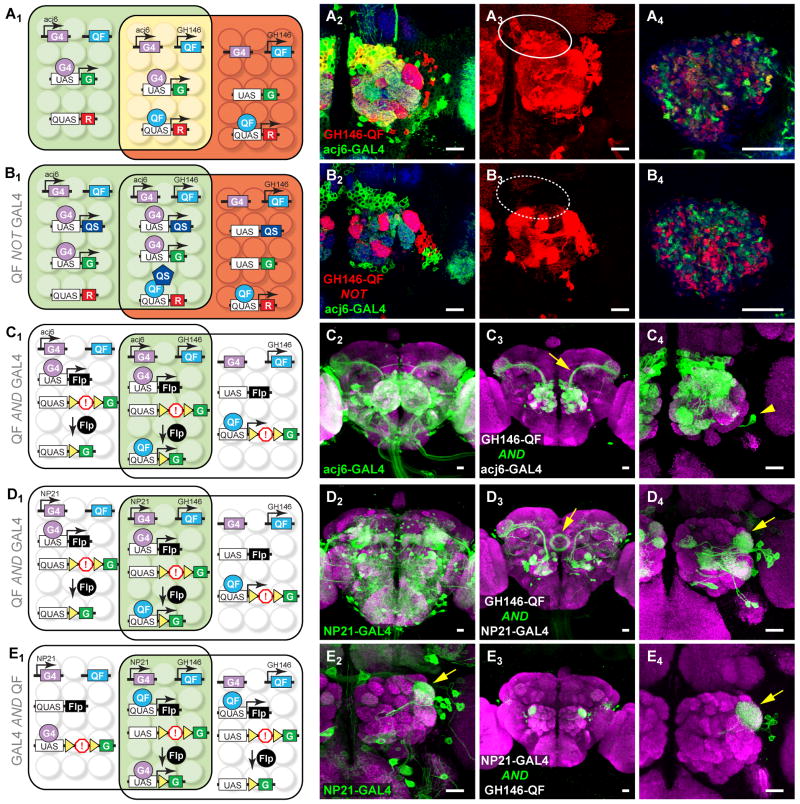

A major power of the GAL4/UAS system is its ability to manipulate many cell types through thousands of GAL4 lines generated by enhancer trapping or GAL4 fusions to specific promoters. Despite the abundance of GAL4 lines, their expression patterns are often too broad to establish the causality between the expression of a transgene in a particular cell type and a phenotype, especially if the phenotype is assayed at the organismal level. Combining GAL4- and QF-based binary systems into logic gates can create new expression patterns (Figure S6). Below we provide proof-of-principle examples for some of these strategies (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Intersectional Methods to Refine Transgene Expression.

(A1) Schematic showing two partially overlapping cell populations: one expressing an acj6-GAL4-driven green marker (within the left rectangle), and the other expressing a GH146-QF-driven red marker (within the right rectangle). Cells in the center express both GAL4 and QF and appear yellow.

(A2-A4) Single confocal sections (A2, A4) or a z-projection (A3) of the adult antennal lobe (A2-A3) or mushroom body calyx (A4) from flies with the genotype shown in A1. Green, red and yellow cells in A2 represent PNs that express acj6-GAL4 only, GH146-QF only, or both, respectively. Their dendrites form green, yellow and red glomeruli (A2). Their axons form green, red, and yellow terminal boutons in the mushroom body (A4). (A3) is the z-projection of the red channel for A2; the oval highlights cell bodies of anterodorsal PNs. Green: anti-CD8 staining for UAS-mCD8-GFP; Red: anti-HA staining for QUAS-mtdT-HA. Blue: neuropil marker.

(B1) Schematic for ‘QF NOT GAL4’ for acj6-GAL4 and GH146-QF. UAS-QS is added to A1, resulting in the repression of QF activity in cells that express both QF and GAL4 (center). QF reporter expression is thus subtracted from the overlapping population of cells.

(B2-B4) Equivalent samples as A2-A4, except with UAS-QS added. Compared to A3, anterodorsal PNs no longer express QUAS-mtdT-HA (dotted oval in B3). There are no yellow cells and glomeruli in the antennal lobe (B2), or yellow terminal boutons in the mushroom body (B4).

Note: In the experiments shown in A and B, to clearly visualize only non-ORN processes in the antennal lobe, antennae and maxillary palps were removed 10 days prior to staining, causing all Acj6-expressing ORN axons to degenerate.

(C1) Schematic for “QF AND GAL4” for acj6-GAL4 and GH146-QF. GAL4 driven FLP results in the removal of a transcriptional stop (!) from a QUAS reporter (within the left rectangle), but the reporter can only be expressed in cells where QF is expressed (within the right rectangle). Thus, only the cells in the overlap (center) express the reporter.

(C2) Confocal stack of a whole mount central brain showing reporter (mCD8-GFP) expression from acj6-GAL4, which labels many types of neurons including most ORNs, olfactory PNs and optic lobe neurons.

(C3-C4) The AND gate between GH146-QF and acj6-GAL4 (genotype as in C1) limits mCD8-GFP expression to a cluster of anterodorsal PNs and a single lateral neuron (arrowhead in C4). Arrow in C3, axons of anterodorsal PNs.

(D1) Schematic for “QF AND GAL4” similar to C1, but for NP21-GAL4 and GH146-QF.

(D2) Confocal stack of whole mount central brain showing reporter (mCD8-GFP) expression from NP21-GAL4.

(D3-D4) The AND gate between GH146-QF and NP21-GAL4 limits reporter expression to a few classes of PNs that project to several glomeruli including DA1 (arrow in D4) and to neurons that project to the ellipsoid body (arrow in D3).

(E1) Schematic for an alternative approach to “GAL4 AND QF” for NP21-GAL4 and GH146-QF. Here, FLP is driven by QF, and the reporter is driven by GAL4.

(E2) High magnification of NP21-GAL4 expression pattern centered at the antennal lobe. In the adult, only one class of lateral PNs projecting to the DA1 glomerulus (arrow) is evident.

(E3-E4) This AND gate between GH146-QF and NP21-GAL4 limits expression to a single class of lateral PNs that project to the DA1 glomerulus (arrow in E4). Occasional expression is also found in a few cells in the anterior lateral region of the brain.

Genotypes: (A) acj6-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-mCD8-GFP, QUAS-mtdT-HA; (B) acj6-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-mCD8-GFP, QUAS-mtdT-HA, UAS-QS; (C2) acj6-GAL4, UAS-mCD8-GFP; (C3, C4) acj6-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-FLP, QUAS>stop>mCD8-GFP; (D2 E2) NP21-GAL4, UAS-mCD8-GFP; (D3, D4) NP21-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-FLP, QUAS>stop>mCD8-GFP; (E3, E4) NP21-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS>stop>mCD8-GFP, QUAS-FLP; “>”, FRT site.

Scale bars: 20 μm.

Figure S6 shows strategies to generate 12 QF and GAL4 intersectional logic gates.

QF NOT GAL4

Like the previously characterized GH146-GAL4 (Jefferis et al., 2001), GH146-QF is expressed in PNs that are derived from the anterodorsal, lateral and ventral neuroblast lineages (Figure 2B). The POU transcription factor Acj6 is expressed only in anterodorsal but not in lateral or ventral GH146-positive PNs (Komiyama et al., 2003). Acj6, and acj6-GAL4, an enhancer trap line inserted into the acj6 locus, are also expressed in some GH146-negative anterodorsal PNs, in many ORNs, in atypical PNs, and in lateral horn output neurons (Clyne et al., 1999; Komiyama et al., 2003; Suster et al., 2003; Komiyama et al., 2004; Jefferis et al., 2007; Lai et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 6A, when GH146-QF and acj6-GAL4 are present in the same fly, and are detected via QUAS-mtdT-HA and UAS-mCD8-GFP, respectively, a large subset of anterodorsal PNs is labeled by both mCD8-GFP and mtdT-HA, whereas lateral and ventral PNs express mtdT-HA but not mCD8-GFP.

By introducing a UAS-QS transgene, we subtracted the GAL4-expressing cells from the QF-expressing cells such that the QUAS-mtdT-HA reporter was only expressed in the lateral and ventral, but not the anterodorsal PNs (Figure 6B; compare Figure 6B3 with 6A3). In this manner, we created ‘QF NOT GAL4’, a new QF-dependent expression pattern. Using this logic gate, we observed non-overlapping glomeruli labeled by Acj6-expressing anterodorsal PNs in green and QF-expressing lateral PNs in red (Figure 6B2). This observation confirms directly in the same animal a previous finding that PNs from the anterodorsal and lateral lineages project dendrites to complementary and non-overlapping glomeruli in the antennal lobe (Jefferis et al., 2001).

Expression pattern subtraction can also be visualized at the level of axon terminals. Both anterodorsal and lateral PNs project their axonal collaterals into the mushroom body calyx, where they terminate in large presynaptic boutons. In the absence of the UAS-QS transgene, these individual terminal boutons are labeled green, yellow and red, representing axon terminals of PNs that are Acj6+/GH146- anterodorsal PNs, Acj6+/GH146+ anterodorsal PNs, and GH146+/Acj6- lateral PNs, respectively (Figure 6A4). In the presence of UAS-QS, yellow terminal boutons are no longer present (Figure 6B4), indicating that acj6-GAL4 labeled cells have been subtracted from the GH146-QF expression pattern. This experiment allows, for the first time, a direct comparison of axon terminal distributions of anterodorsal and lateral PNs co-innervating the same mushroom body.

QF AND GAL4

By introducing two additional transgenes, QUAS-FLP, UAS>stop>effector (Figure 6C1 D1; > represents FRT), or UAS-FLP, QUAS>stop>effector (Figure 6E1), into an animal containing a GAL4 and a QF line, only cells that express both QF and GAL4 (‘QF AND GAL4’) can be selectively visualized and genetically manipulated. Below we show three examples.

First, we studied the intersection of GH146-QF and acj6-GAL4. With the introduction of UAS-FLP and QUAS>stop>mCD8-GFP, anterodorsal PNs that are both Acj6+ and GH146+ were labeled (Figure 6C), confirmed by the glomerular identity of dendritic projections of these neurons (data not shown). A previously described Acj6/GH146 double-positive cell from a separate lineage (Komiyama et al., 2003) was also labeled (Figure 6C4, arrowhead). All other lateral and all ventral GH146+ PNs, which do not express Acj6, no longer expressed the marker. The marker was also not expressed in ORNs or lateral horn neurons, which express Acj6 but not GH146. Thus, we can express transgenes only in cells that express both GH146 and Acj6: a subset of anterodorsal PNs.

In the second and third examples, we studied the intersection between GH146-QF and NP21-GAL4 using two AND gate strategies. NP21-GAL4 is an enhancer trap line inserted near the promoter of fruitless (fru) (Hayashi et al., 2002) that drives the expression of the male-specific isoform of Fru (FruM), which is essential for regulating mating behavior (Demir and Dickson, 2005; Manoli et al., 2005). NP21-GAL4 labels many neurons in the brain (Kimura et al., 2005) (Figure 6D2), including PNs that project dendrites to the DA1 glomerulus (Figure 6E2). In our first strategy (Figure 6D1), we used UAS-FLP and QUAS>stop>mCD8-GFP, and found that ∼10 PNs that innervated several glomeruli were selectively labeled (Figure 6D3, D4). In our second strategy (Figure 6E1), we used QUAS-FLP and UAS>stop>mCD8-GFP, and found that the labeled PNs were restricted to only ∼5 cells that project their dendrites to the DA1 glomerulus (Figure 6E3, E4). The difference between these two strategies reflects the fact that in these intersectional strategies, the binary system used to drive FLP reports the cumulative developmental history, rather than only the adult expression, of the driver. Our data suggest that NP21-GAL4 (and by inference fruM) is expressed in more PN classes during development than in the adult. In both cases, the complex NP21-GAL4 expression pattern outside of PNs has been reduced to very few cells. The comparison of expression patterns from the two strategies can pinpoint the cells that are at the intersection of GH146-QF and NP21-GAL4 adult expression patterns. Future use of a perturbing effector could lead to functional characterization of this small genetically defined group of cells.

Comparisons with other methods

An AND gate can be achieved by utilizing the split-GAL4 system (Luan et al., 2006). The benefit of our method is that it can take advantage of the thousands of available and well-characterized GAL4 lines, whereas the split-GAL4 system needs to generate new split N-GAL4 and C-GAL4 lines. In addition, reconstituted GAL4 from the split GAL4 system is not as strong as wild-type GAL4 in driving transgene expression (Luan et al., 2006).

The intersection between FLP/FRT and GAL4/UAS can also be used directly as an AND gate without going through a second binary system to express FLP (Stockinger et al., 2005; Hong et al., 2009). Both this method and our method have the caveats of transient FLP expression during development, as well as the possibility that FLP/FRT-mediated recombination may not occur in all cells that express FLP. Although our method requires one additional transgene, it offers several advantages over promoter-driven FLP. First, our method does not require the generation of separate tissue or cell type-specific FLP lines. Second, by inducing higher FLP levels due to transcriptional amplification of binary expression, our method should more readily overcome problems of incomplete recombination. Indeed, counts of the number of DA1 projecting PNs that are part of the NP21 expression pattern with or without the AND gate with GH146 are similar (NP21-GAL4: 5.2 ± 0.1, n= 48; GH146-QF/QUAS-FLP AND NP21-GAL4: 5.1 ± 0.1, n=10), suggesting nearly complete FLP/FRT mediated recombination. Third, our method offers two complementary AND gate strategies, which together can be used to overcome the ambiguities arising from transient developmental expression. Fourth, transient developmental expression mediated by QUAS-FLP could in principle be suppressed by introducing tubP-QS, and the suppression could be reversed by supplying the flies with quinic acid at appropriate developmental stages.

The ‘QF NOT GAL4’ or ‘GAL4 NOT QF’ (Figure S6) strategies are conceptually similar to GAL80 subtraction of GAL4 expression (Lee and Luo, 1999). If one were to generate a large number of GAL80 enhancer trap or promoter driven lines, one could use this set to subtract their expression patterns from GAL4 expression patterns. One limitation of this approach is that the GAL80 expression pattern is difficult to determine at high resolution because it is based on suppression of GAL4-induced gene expression. In addition, GAL80 levels must be sufficiently high to ensure proper suppression of GAL4, which may not be true for many enhancer trap or promoter-driven GAL80 transgenes. By contrast, the ‘NOT’ gate we describe here utilizes the expression patterns of two transcription factors, which express the appropriate repressor through binary amplification, and should therefore circumvent both limitations above.

A major limitation of our intersectional strategies for refinement of gene expression is the availability of QF drivers with different expression patterns. So far, we were unsuccessful in generating tubP-QF transgenic animals, suggesting that QF is toxic to flies when highly expressed in a ubiquitous manner or in a particular developmental stage or tissue (see Extended Experimental Procedures). Nonetheless, we isolated many QF enhancer traps that express strongly in imaginal discs, epithelial tissues, glia, and neurons (Figure S2B-C). We hope that our proof-of-principle examples here will stimulate the Drosophila community to generate large numbers of enhancer trap and promoter-driven QF lines in the future. The number of new expression patterns created by intersections between GAL4 and QF should be multiplicative. For instance, 100 QF lines in combination with 10,000 GAL4 lines, given sufficient expression overlap and utilizing different logic gates (Figure S6), should in principle generate millions of new effector expression patterns.

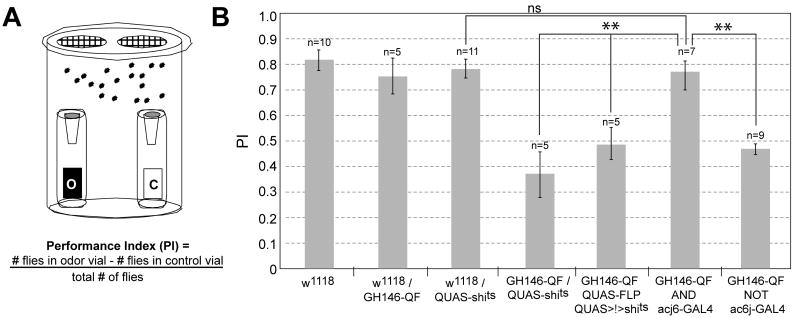

Defining PNs Responsible for Olfactory Attraction

By expressing an effector that alters neuronal activity, intersectional approaches can be used to dissect the function of neuronal circuits. We used this approach to assay the function of PNs in an olfactory attraction behavior. Instead of expressing a marker in specific populations of neurons, we expressed shibirets1 (shits), a temperature sensitive variant of the protein dynamin that dominantly interferes with synaptic vesicle recycling (Kitamoto, 2001). At the non-permissive temperature, synaptic transmission of neurons that express shits is reversibly inhibited. This approach allowed us to selectively inhibit different populations of PNs — lateral and ventral (GH146-QF NOT acj6-GAL4; Figure 6B) or anterodorsal (GH146-QF AND acj6-GAL4; Figure 6C) — and then assay behavioral attraction to the fruity odorant ethyl acetate using a modified trap assay (Larsson et al., 2004) (Figure 7). Similar to controls, flies containing only GH146-QF or QUAS-shits exhibited strong attraction to ethyl acetate. When all GH146+ PNs were inhibited (GH146-QF+QUAS-shits or GH146-QF+QUAS-FLP+QUAS>stop>shits), there was a significant deficit in olfactory attraction. However, when only anterodorsal GH146+ PNs were inhibited, attraction remained normal. In contrast, when lateral/ventral GH146+ PNs were inhibited, there was a deficit in olfactory attraction akin to the inhibition of all GH146+ PNs. These results suggest that, in this behavioral context, attraction to ethyl acetate is mediated by the lateral/ventral, and not anterodorsal, subpopulations of PNs.

Figure 7. Defining PNs Responsible for Olfactory Attraction Using Intersectional Methods.

(A) Schematic of the olfactory trap assay. O,1% ethyl acetate in mineral oil; C, control (mineral oil alone). A performance index (PI) is used to measure olfactory attraction.

(B) Performance index plots of flies of listed genotypes. Error bars are ± SEM. **, p≤0.01. ns, not significant.

Genotypes: (GH146-QF AND acj6-GAL4) acj6-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-FLP, QUAS>stop>shibirets1; (GH146-QF NOT acj6-GAL4) acj6-GAL4, GH146-QF, UAS-QS, QUAS-shibirets1. “>”, FRT site; “>!>”, transcriptional stop>.

Conclusions and Perspectives

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the Q repressible binary expression system functions well outside its native Neurospora, from cultured Drosophila and mammalian cells to Drosophila in vivo. We have generated and validated a substantial number of tools (Table S1, Figure S2, S7) that can be used for many applications, as illustrated by the examples given above. Below we discuss a few future developments and applications.

Genetic dissection of neural circuits

Drosophila has emerged as an attractive model system to establish causal links between the functions of individual classes of neurons, information processing within neural circuits, and animal behavior. A bottleneck in this endeavor is the genetic access to specific populations of neurons with reproducible precision, such that one can label them with markers for anatomical analysis, express genetically encoded indicators to record their activity, and silence or activate these neurons to examine the consequences to circuit output or to animal behavior (Luo et al., 2008). The intersectional methods we describe should greatly increase the precision of genetic access to specific neuronal populations, especially as more QF drivers are characterized.

High-resolution mosaic analysis

Although MARCM is a powerful tool for identification and functional studies of genes that act cell autonomously, it is less adaptable to studies of genes that act non-cell autonomously. The ability to perform MARCM analysis independently from GAL4/UAS should expand the power of mosaic analysis for genes that function in intercellular communication. For example, using GAL4/UAS, one can perturb the function of a group of cells, while using Q-MARCM to examine the consequences of the perturbation on a small subset of interacting cells. Furthermore, both systems can be used in the same animal for independent perturbations of two populations of interacting cells, via both loss- and gain-of-function approaches. Finally, these approaches can be expanded into genetic screens where, for example, the GAL4 binary system is used to drive an RNAi library in a large group of cells while the Q system is used to label a small population of neurons with high resolution.

Beyond the nervous system and Drosophila

The Q system should be widely applicable beyond the Drosophila nervous system. We have provided an example of clonal phenotypic analysis in the wing disc for cell growth and proliferation. Similar studies could be used for the identification and characterization of tumor suppressors or oncogenes that function cell autonomously or non-autonomously. The Q system should in principle permit transgene expression, lineage and mosaic analysis in many other Drosophila tissues. Finally, QF/QUAS-induced transgene expression is ∼30 fold more effective in mammalian cells compared with GAL4/UAS. This fact may make the Q binary expression system more effective than GAL4/UAS for transgene expression in mice (Ornitz et al., 1991; Rowitch et al., 1999). Indeed the Q system could be extended to all organisms conducive to transgenesis.

Experimental Procedures

QF and QS cDNAs were obtained by PCR using a cosmid, pLorist-HO35F3 from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center, as the template. QUAS was constructed using 5 copies of naturally occurring QF binding sites (each 16 bp long, shown in capital letters, with spacer sequences in small letters): GGGTAATCGCTTATCCtcGGATAAACAATTATCCtcacGGGTAATCGCTTATCCgctcGGGTAATCGCTTATCCtcGGGTAATCGCTTATCCtt.

See Extended Experimental Procedures for details on the construction of plasmids and transgenic flies, cell transfection, Drosophila genetics, mosaic analysis, imaging and behavior.

All plasmids and sequence files are deposited to Addgene. Most fly stocks in Table S1 are deposited to the Bloomington Stock Center. Other fly stocks are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Luginbuhl, M. Tynan La Fontaine and T. Chou for technical assistance, K. Wehner for HeLa cells, mouse anti-HA, and mouse anti-fibrillarin antibodies, M. Simon for S2 cells and adult eye sectioning, T. Clandinin for 24B10 antibodies, S. Block for luminometer usage, Fungal Genetics Stock Center for cosmids containing QF and QS, Developmental Biology Hybridoma Bank for monoclonal antibodies, Bloomington Stock Center for flies, D. Berdnik, Y.-H. Chou, K. Miyamichi, M. Spletter, L. Sweeney and W. Hong for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Human Frontiers Science Program. CJP and BT were supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CJP: DRG-1766-03; BT: DRG-1819-04). L. Liang was supported by the Stanford Graduate Fellowship. L. Luo is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

CJP performed all the Drosophila in vivo experiments, with the help of EVR. BT identified the qa system from Neurospora as a candidate binary expression system and performed the Drosophila and mammalian cultured cell experiments. L. Liang performed the quantitative analysis in Figure 5. L. Luo supervised the project, and wrote the paper with CJP and BT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baum JA, Geever R, Giles NH. Expression of qa-1F activator protein: identification of upstream binding sites in the qa gene cluster and localization of the DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1256–1266. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdnik D, Fan AP, Potter CJ, Luo L. MicroRNA processing pathway regulates olfactory neuron morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1754–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant PJ, Simpson P. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of growth in developing organs. Q Rev Biol. 1984;59:387–415. doi: 10.1086/414040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne PJ, Certel SJ, de Bruyne M, Zaslavsky L, Johnson WA, Carlson JR. The odor specificities of a subset of olfactory receptor neurons are governed by Acj6, a POU-domain transcription factor. Neuron. 1999;22:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E, Dickson BJ. fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JA, Giniger E, Maniatis T, Ptashne M. GAL4 activates transcription in Drosophila. Nature. 1988;332:853–856. doi: 10.1038/332853a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles NH, Geever RF, Asch DK, Avalos J, Case ME. The Wilhelmine E. Key 1989 invitational lecture. Organization and regulation of the qa (quinic acid) genes in Neurospora crassa and other fungi. J Hered. 1991;82:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jhered/82.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golic KG, Lindquist S. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell. 1989;59:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin R, Sustar A, Bonvin M, Binari R, del Valle Rodriguez A, Hohl AM, Bateman JR, Villalta C, Heffern E, Grunwald D, et al. The twin spot generator for differential Drosophila lineage analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:600–602. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Ito K, Sado Y, Taniguchi M, Akimoto A, Takeuchi H, Aigaki T, Matsuzaki F, Nakagoshi H, Tanimura T, et al. GETDB, a database compiling expression patterns and molecular locations of a collection of Gal4 enhancer traps. Genesis. 2002;34:58–61. doi: 10.1002/gene.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Zhu H, Potter CJ, Barsh G, Kurusu M, Zinn K, Luo L. Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane proteins instruct discrete dendrite targeting in an olfactory map. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1542–1550. doi: 10.1038/nn.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huiet L, Giles NH. The qa repressor gene of Neurospora crassa: wild-type and mutant nucleotide sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3381–3385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N, Rubin GM. gigas, a Drosophila homolog of tuberous sclerosis gene product-2, regulates the cell cycle. Cell. 1999;96:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis GS, Potter CJ, Chan AM, Marin EC, Rohlfing T, Maurer CR, Jr, Luo L. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell. 2007;128:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis GSXE, Marin EC, Stocker RF, Luo L. Target neuron prespecification in the olfactory map of Drosophila. Nature. 2001;414:204–208. doi: 10.1038/35102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ote M, Tazawa T, Yamamoto D. Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature. 2005;438:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature04229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto T. Conditional modification of behavior in Drosophila by targeted expression of a temperature-sensitive shibire allele in defined neurons. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:81–92. doi: 10.1002/neu.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama T, Carlson JR, Luo L. Olfactory receptor neuron axon targeting: intrinsic transcriptional control and hierarchical interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:819–825. doi: 10.1038/nn1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama T, Johnson WA, Luo L, Jefferis GS. From lineage to wiring specificity: POU domain transcription factors control precise connections of Drosophila olfactory projection neurons. Cell. 2003;112:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SL, Awasaki T, Ito K, Lee T. Clonal analysis of Drosophila antennal lobe neurons: diverse neuronal architectures in the lateral neuroblast lineage. Development. 2008;135:2883–2893. doi: 10.1242/dev.024380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SL, Lee T. Genetic mosaic with dual binary transcriptional systems in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:703–709. doi: 10.1038/nn1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, Vosshall LB. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Lee A, Luo L. Development of the Drosophila mushroom bodies: sequential generation of three distinct types of neurons from a neuroblast. Development. 1999;126:4065–4076. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.18.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Lai SL, Yu HH, Chihara T, Luo L, Lee T. Lineage-specific effects of Notch/Numb signaling in post-embryonic development of the Drosophila brain. Development. 2010;137:43–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.041699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan H, Peabody NC, Vinson CR, White BH. Refined spatial manipulation of neuronal function by combinatorial restriction of transgene expression. Neuron. 2006;52:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L. Fly MARCM and mouse MADM: genetic methods of labeling and manipulating single neurons. Brain Res Rev. 2007;55:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K. Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron. 2008;57:634–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli DS, Foss M, Villella A, Taylor BJ, Hall JC, Baker BS. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nature03859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin EC, Jefferis GSXE, Komiyama T, Zhu H, Luo L. Representation of the glomerular olfactory map in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2002;109:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin EC, Watts RJ, Tanaka NK, Ito K, Luo L. Developmentally programmed remodeling of the Drosophila olfactory circuit. Development. 2005;132:725–737. doi: 10.1242/dev.01614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, Matsumoto K, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet LML. Food analysis by HLPC. 2nd. CRC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlander RH, Edwards JS. Postembryonic brain development in the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus pleisippus, L. I. cellular events during brain morphogenesis. Wilhelm Roux' rchiv. 1969;162:197–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00576929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, Moreadith RW, Leder P. Binary system for regulating transgene expression in mice: targeting int-2 gene expression with yeast GAL4/UAS control elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel VB, Schweizer M, Dykstra CC, Kushner SR, Giles NH. Genetic organization and transcriptional regulation in the qa gene cluster of Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:5783–5787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer BD, Jenett A, Hammonds AS, Ngo TT, Misra S, Murphy C, Scully A, Carlson JW, Wan KH, Laverty TR, et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Huang H, Xu T. Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell. 2001;105:357–368. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P, Szabo K, Bailey A, Laverty T, Rehm J, Rubin GM, Weigmann K, Milan M, Benes V, Ansorge W, Cohen SM. Systematic gain-of-function genetics in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125:1049–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowitch DH, B SJ, Lee SM, Flax JD, Snyder EY, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and inhibits differentiation of CNS precursor cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8954–8965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08954.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RF, Heimbeck G, Gendre N, de Belle JS. Neuroblast ablation in Drosophila P[GAL4] lines reveals origins of olfactory interneurons. J Neurobiol. 1997;32:443–456. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199705)32:5<443::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger P, Kvitsiani D, Rotkopf S, Tirian L, Dickson BJ. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell. 2005;121:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suster ML, Martin JR, Sung C, Robinow S. Targeted expression of tetanus toxin reveals sets of neurons involved in larval locomotion in Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:233–246. doi: 10.1002/neu.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Ito N, Dickson BJ, Treisman JE, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila tuberous sclerosis complex gene homologs restrict cell growth and cell proliferation. Cell. 2001;105:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Chen CH, Shi L, Huang Y, Lee T. Twin-spot MARCM to reveal the developmental origin and identity of neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:947–953. doi: 10.1038/nn.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.