Abstract

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a painful and disabling disorder that can affect one or more extremities. Unfortunately, the knowledge concerning its natural history and mechanism is very limited and many current rationales in treatment of CRPS are mainly dependent on efficacy originated in other common conditions of neuropathic pain. Therefore, in this study, we present a case using a total spinal block (TSB) for the refractory pain management of a 16-year-old male CRPS patient, who suffered from constant stabbing and squeezing pain, with severe touch allodynia in the left upper extremity following an operation of chondroblastoma. After the TSB, the patient's continuous and spontaneous pain became mild and the allodynia disappeared and maintained decreased for 1 month.

Keywords: complex regional pain syndrome, total spinal block

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic pain syndrome which is marked by spontaneous pain, allodynia, and hyperalgesia in one or more of four limbs, accompanying by dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system and motor nerve system. Because there is no definitive diagnostic tool or treatment until now, it has been difficult to manage CRPS patients in clinics [1]. Therefore, we report a case of a 16-year-old CRPS male patient with pain that we couldn't control through many kinds of management, including epidural catheterization, sympathetic block, intravenous injection of local anesthetics and ketamine according to the patient's symptoms, but we observed a reduced pain scale for allodynia and spontaneous pain for 1 month after the total spinal block (TSB).

CASE REPORT

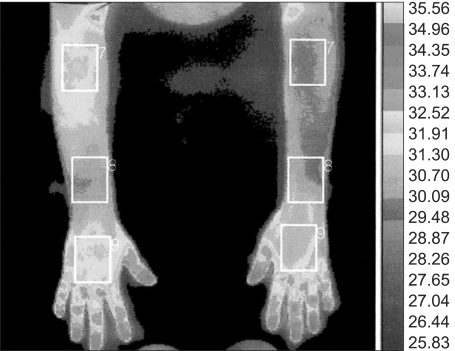

A 16-year-old male patient came to our clinic for pain that was like continuous stabbing and electrical shock in left shoulder and forearm, as well as a and decreased power in hand grip. He had an excision and biopsy operation of chondroblastoma in the left humeral head 1 month previously and developed a continuous pain without any nerve damage on electromyelography. The visual analogue scale for pain (VAS) was 70/100 and hyperalgesia, allodynia, muscular atrophy and tremor of left forearm were observed on physical examination. The delayed phase of a 3 phase bone scan showed an increase of vascular flow on the left humeral head and an infra red image of upper limbs revealed the temperature of the left forearm was lower than the right one by 1.72 degree (Fig. 1). By his symptoms, physical examinations, and the infra red images, we diagnosed the patient as having CRPS type 1 and started oral medication and tried continuous cervical epidural catheterization, thoracic sympathetic ganglion block, cervical nerve root block, brachial plexus block and intravenous injection of local anesthetics and ketamin, so his symptoms were controlled around 40/100 on VAS. However, after summer vacation, while attending school regularly, the patient complained about having severe pain several times a day because of making contact with friends and he was rushed to the emergency room more often than before, and did not respond to any of treatments that we had used before with success. VAS was 80/100 and getting more severe and broadening to the tips of the left hand fingers; especially, he felt a cutting-like pain on the left fifth finger, allodynia even with breeze and squeezing pain, and a limited range of motion with tremor. We initially considered spinal cord stimulator insertion at first, but we were afraid of stimulation electrode migration because the patient was still growing 8 centimeters per year. Therefore we decided to try TSB and explained about the validity of using this procedure for uncontrollerable pain, We also explained the side effects and received informed consents for vascular instability, pneumonia or sepsis from mechanical ventilation and late recovery from unconsciousness and death. After infusing 300-500 ml of normal saline for 30 minutes in the operating room, we monitored continuous arterial pressure on the radial artery, oxygen saturation, electrocardiogram and bispectral index (BIS). While the patient was lying at the right lateral decubitus position, a 25 G spinal needle was inserted between the third and fourth lumbar intervertebral space and cerebrospinal fluid was checked flowing freely; fyrtherfore, and injected 1.5% lidocaine 30 ml by 10 ml was injected incrementally, slower than 1 ml per 1 second for 1 minute. After finishing the injection of local anesthetics and laying the patient in a supine position, we intravenously injected 100 mg Pentothal sodium and 3 mg midazolam intravenously for decreasing the uncomfortable sense the patient might feel during the start of TSB. Supplying 100% oxygen 6 L per minute by mask, we observed the process of loss of consciousness and inserted a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) without muscle relaxant. Ventilating mechanically with a tidal volume of 600 ml and minute volume of 7.2 L, we maintained an end-tidal carbon dioxide level between 35 and 40 mmHg. Following 2 hours of LMA insertion, spontaneous breathing was recovered and we removed the LMA. There was no respiratory problem at the recovery room. Before the procedure, the patient's blood pressure was 150/70 mmHg. Ten minutes later, it decreased to 100/60 mmHg; no further decrease of blood pressure occured and it increased to 140/80 mmHg and remained so along with the patient's recovery of consciousness. The patient was transported to a general ward. Blood pressure and oxygen saturation were normal when we monitored him for 1 day after the procedure. The pain was 10/100 VAS in the left shoulder and forearm, dull and mild. Severe pain on the left fifth finger and dysesthesia in the left forearm disappeared. The range of motion was improved, and the patient didn't complain of tremor any more. After his discharge, the pain scale remained the same, being reduced for 1 month, but it later was increased to 60/100 VAS because of some emotional stress and then was reduced to 40/100 again.

Fig. 1.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (M/16). This picture shows the thermogram and temperature of the patient painful skin lesion site upper limb.

DISCUSSION

CRPS is a chronic pain syndrome of which the pathophysiology is revealed clearly. However, the peripheral nervous system disorder accompanying the inflammation and ischemia take part in the pathophysiology and dysfunction of the central nervous system and sympathetic nervous system as well. Responses to the same treatment may be different as the symptoms, in the same patient it can be different other times [2]. Therefore, various treatments should be tried according to the physician's knowledge and experience, and taking into consideration patient's pain character and emotional stress and general health, as there is no typical treatment to for CRPS patients [1].

The objects of CRPS treatment are an exact and early diagnosis as well as an active and multidisciplinary approach for maximal pain reduction and recovery for daily life; therefore appropriate treatment should be started as soon as possible [3]. In this case pain developed without nerve damage just following the excision and biopsy operation of chondroblastoma in the left humeral head. The patient was immediately referred to a pain clinic and given an early diagnosis, so that pain was managed through intensive pain control during hospitalization. However, after the patient's discharge, pain induced by some physical contact with others could not be reduced by any method that had previously been effective. It was six months since we began pain control in this patient. We considered spinal cord stimulator insertion [4], but he was still growing very quickly and we were afraid of migration of the electrode, so we tried TSB [5].

TSB is blockade of the spinal cord and brain by a large quantity of local anesthetics injected into the subarachnoid space. Its indications are CRPS, post herpetic neuralgia, phantom pain and so on. TSB has been performed over 1,300 times since it was first tried in 1972 at a Japanese hospital, but the numbers of cases are becoming reducing as other, various nerve blocks are being used [6]. Kimura et al. [7] and Goda et al. [8] reported that TSB increases vagal nerve activity at the early stage of blockade, reduces sympathetic activity but relatively increases parasympathetic activity at the late stage of blockade on the power spectral analysis of the heart rate and peripheral blood flow variations. Therefore, we expect that TSB may contribute to the recovery of balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system and sympathetic chronic pain control. TSB may suppress ectopic discharge from the injured peripheral nerve at the supraspinal level by injection of a large quantity of local anesthetics injection into the subarachnoid space and effects the central nervous system changes on abnormal perception and nociception [9].

TSB was first described clinically when a patient with whiplash injury experienced pain reduction after accidental TSB during the epidural block. There is also the case of transient hearing loss following repeated total spinal anesthesias [10], Yokoyama et al. [11] and Cheon et al. [9] report there was no hemodynamic instability in their cases, and the unexpected loss of consciousness loss was slowly recovered, following the recovery of respiration. Additionally, promoting safety by careful preparation and using local anesthetics diversely is recommended. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows changes in the primary sensory area, primary motor area, and temporal lobe of the cerebrum of a CRPS patient [12], so evaluating the effect of TSB by comparing functional MRI images before and after the procedure is necessary.

In conclusion, TSB is one of the treatments worth trying to treat CRPS patient with sympathetic maintained pain and changes in the central nervous system.

References

- 1.de Mos M, de Bruijn AG, Huygen FJ, Dieleman JP, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC. The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome: a population-based study. Pain. 2007;129:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribbers GM, Geurts AC, Stam HJ, Mulder T. Pharmacologic treatment of complex regional pain syndrome I: a conceptual framework. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:141–146. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanton-Hicks M, Baron R, Boas R, Gordh T, Harden N, Hendler N, et al. Complex regional pain syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:155–166. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199806000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilder RT. Management of pediatric patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:443–448. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000194283.59132.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JJ, Moon DE, Park SJ, Choi JI, Shim JC. Cervical and thoracic spinal cord stimulation in a patient with pediatric complex regional pain syndrome: a case report. Korean J Pain. 2007;20:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh HG, Cha YD, Yoon DM. Pain clinic nerve block. Seoul: Koonja Publishing Inc; 1995. pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura T, Komatsu T, Hirabayashi A, Sakuma I, Shimada Y. Autonomic imbalance of the heart during total spinal anesthesia evaluated by spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:694–698. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199403000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goda Y, Kimura T, Goto Y, Kemmotsu O. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and peripheral blood flow variations during total spinal anesthesia. Masui. 1989;38:1275–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheon BS, Han KR, Kim JS, Kim YS, Kim C. A case of total spinal anesthesia for treatment of phantom limb pain: a case report. Korean J Pain. 2003;16:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SY, Han KR, Kim JS, Yoon C, Chae YJ, Kim C. Transient hearing loss following repeated total spinal anesthesias: a case report. Korean J Pain. 2003;16:282–285. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama M, Itano Y, Kusume Y, Oe K, Mizobuchi S, Morita K. Total spinal anesthesia provides transient relief of intractable pain. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:810–813. doi: 10.1007/BF03017413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HM, Park HL, Song SO. Functional MRI findings showing cortical reorganization in a patient with type 2 complex regional pain syndrome: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2009;56:353–357. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2009.56.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]