Abstract

Objectives:

(1) To explore the effects on women's lives by heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding; (2) To examine whether aspects of women's lives most affected by heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding were adequately addressed by questions that are frequently used in clinical encounters and available questionnaires.

Methods:

We conducted four focus group sessions with a total of 25 English-speaking women who had reported abnormal uterine bleeding. Discussions included open-ended questions that pertained to bleeding, aspects of life affected by bleeding, and questions frequently used in clinical settings about bleeding and quality of life.

Results:

We identified five themes that reflected how women's lives were affected by heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding: irritation/inconvenience, bleeding-associated pain, self-consciousness about odor, social embarrassment, and ritual like behavior. Although women responded that the frequently used questions about bleeding and quality of life were important, they felt that the questions failed to go into enough depth to adequately characterize their experiences.

Conclusions:

Based on the themes identified in our focus group sessions, clinicians and researchers may need to change the questions used to capture “patient experience” with abnormal uterine bleeding more accurately.

Keywords: heavy menstrual bleeding, abnormal uterine bleeding, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is any alteration in the volume or pattern of menstrual blood flow. Two main categories of AUB are heavy menstrual bleeding and irregular menstrual bleeding, and many patients experience the combination of these symptoms. (Lobo, 2007) Menstrual disorders are the most frequent gynecologic condition in the general population and have a major impact on quality of life (Kjerulff et al., 1996).

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman's physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life, affects up to 30% of women at some time in their reproductive years and has a major impact on quality of life (NICE 2007; Kjerulff et al., 1996; Barnard et al., 2003; MORI 1990; Cote et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2007). Traditionally, research on HMB has objectively measured menstrual blood loss as the main study outcome and defined “heavy bleeding” as more than 80 mls blood lost per cycle (Hallberg et al., 1966). However, in clinical practice, the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding are based upon “patient experience”, the woman's personal assessment of her blood loss and its impact on her life. Studies have shown that measured blood loss does not provide a comprehensive picture of the patient experience with bleeding (Haynes et al., 1977; Warner et al., 2004; O'Flynn and Britten, 2000).

Irregular menses are academically defined as menses with cycle to cycle variation of greater than 20 days total over one year (Fraser et al., 2007). Irregular menstrual bleeding occurs very frequently following menarche and during the progression from late reproductive life in the late thirties to the menopausal transition (Lisabeth et al., 2004). “Patient experience” with irregular bleeding is important because women with irregular menstrual bleeding have difficulty “predicting” when they will get their menstrual period and may experience staining of their clothes and embarrassing accidents.

Recent research in the area of AUB has recognized the importance of the “patient experience” as an outcome that should be measured (Clark et al., 2002). Because of this, patient-based outcome measures (PBOMs) and questionnaires of varying quality have been developed and used for clinical research in the area. Many of these questionnaires incorporate questions typically used by health care providers in clinical encounters with women with heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding, although no single PBOM or questionnaire is accepted as the “standard of care” for evaluating women with AUB in the clinical setting or in research (Matteson et al., 2008).

In the United States, limited studies have qualitatively examined how women with AUB feel and function both during their menstrual period and between menstrual periods (Elson, 2002). Several published qualitative studies, using semi-structured interviews, have investigated the quality of life of women in the United Kingdom who report heavy menstrual bleeding (Santer et al., 2007; Santer et al., 2008; Echlin et al., 2002). A meta-ethnography of qualitative studies in this area concluded that the medical model of heavy menstrual bleeding is not useful to patients or healthcare providers because the patient's experience with bleeding cannot be readily observed or quantified by the clinician (Garside et al., 2008). Defining the aspects of women's lives most affected by heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding may facilitate more meaningful interactions between women with AUB and their healthcare provider.

For this study, we conducted focus group sessions to explore the effects on women's lives of heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding and to examine whether aspects of women's lives most affected by heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding were being adequately addressed by questions frequently used in clinical encounters and available questionnaires. Specifically, we explored how women with heavy or irregular menstrual periods discussed their bleeding and how their bleeding affected various aspects of their lives, including social interactions, work, and mood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment

For participation in focus group sessions, we recruited women from the Women's Primary Care Center (WPCC) of Women and Infants Hospital (WIH) and from a large private Obstetrics and Gynecology practice affiliated with WIH. Participants were recruited using both flyers (in the WPCC and the private office) and direct recruitment by a research assistant in the WPCC. A trained research assistant approached a convenience sample of English-speaking patients aged 18 years and over (identified on the face-sheet of the medical chart) who presented for any gynecologic appointment with abnormal uterine bleeding listed as a past medical problem or a reason for the visit. The WIH Institutional Review Board approved this protocol.

Eligibility and Informed consent

Women were eligible for this study if they were 18 years of age and older, self-reported heavy menstrual bleeding, were not currently pregnant, were willing to discuss their bleeding with a group of other women, and were able to give informed consent. Eligibility of interested patients was determined by a standardized screening form, containing a series of questions determining the participant's age, her ability to participate fully in the focus group, and the nature of the problems with her menstrual periods. For the latter criterion, to be eligible, women had to answer “yes” to at least two of the three following questions: “On average, during the last three months, did your period last for 8 days or longer?”, “On average, during the last three months, were your periods irregular?”, and “On average, during the last three months, would you describe your periods as heavy?”

We obtained detailed contact information and informed consent from all eligible participants. Eligible participants were contacted by telephone and a total of 4 focus group sessions were scheduled.

Focus group sessions

The four focus group sessions were conducted in spring 2008. At each focus group session, while waiting for the focus group discussions to begin, women individually reviewed a series of frequently asked questions about their menstrual periods using handheld computers. (Ruta et al, 1995; Coulter et al., 1994) These questions were obtained from previous studies on heavy menstrual bleeding and most questions were from two specific questionnaires: (1) the AMSS, a retrospective questionnaire with a 3-month reference period, which contains 13 questions; and (2) a standard set of questions developed by gynecologists in Oxford, England. (Coulter et al., 1994) Questions included pertained to the duration of the period, the amount of bleeding experienced, the use of sanitary products during menses, the regularity or predictability of menstrual cycles, the effect of periods on work and daily activities, pain, soiling/staining, and sex-life.

Women then participated in approximately 90 minutes of structured focus group discussion. These focus group sessions were led by a trained moderator (MAC) and attended by the principal investigator (KAM), who functioned as an assistant moderator, and a research assistant. For the discussion, the group was first oriented to the topic of heavy menstrual bleeding. Open-ended questions on the personal meaning of the term “heavy period” were asked. Next, women were led through a discussion of the questions about menstrual periods that they had reviewed individually at the beginning of the focus group session (Ruta et al., 1995; Coulter et al., 1994). During each focus group, women independently rated each question as “very important”, “somewhat important”, and “not important” using a card sort. The questions where a majority of women responded either “very important” or “not important” were then discussed in detail.

The remainder of the session was conducted using a script of open-ended questions sequenced to provide maximum insight. Questions centered on their experiences of living life with heavy or irregular menses, what these women with AUB found most inconvenient, what caused them to seek medical care in the past, and what factors had the greatest impact upon their quality of life. Before concluding the session, participants were asked to summarize their thoughts about AUB. Then, the moderator provided a summary of the session and participants were given a chance to respond to the moderator's summary. At the conclusion of the focus group session, participants were paid up to $50 for their participation in the study, transportation, and child care.

Data and analyses

The assistant moderator and research assistant took notes during the focus group sessions. We obtained permission from the participants to audio record the session. At the conclusion of each focus group session, the moderator, assistant moderator, and research assistant had a debriefing session in which they summarized what had transpired in the session. Audio tapes were de-identified and then transcribed by the research assistant. Each session built upon the information gathered in previous sessions. Focus group discussions were repeated until saturation was obtained.

For the interpretive process of this study, we studied notes from the session, transcribed notes from the audio tapes, and the actual audio recordings. Each audio-recording and transcript was reviewed in iterative fashion by two coders (KM, EC) who immersed themselves within the text. Coders organized the transcripts into emerging “themes” which were refined in each review. Discrepancies, if encountered, were resolved by a third reviewer (MAC). The research team discussed the connection of these themes and returned again to the transcripts to confirm that the themes and connections between themes adequately represented the content of the focus group discussions.

RESULTS

A total of 71 women completed the screening process for this study. Nine women were not interested in participating (12.7%), and 2 women did not meet the criteria for abnormal bleeding. Thirty-three women were scheduled to participate in sessions (46.5%). The remaining 38 women either could not be reached by telephone or could not participate at the times that the focus groups were being conducted. Twenty-five of the 33 women scheduled to participate actually participated (35/69, 36% of eligible patients). The results presented reflect the opinions of the 25 women who participated in four focus group sessions. The four focus group sessions were comprised of 7, 5, 5, and 8 women, respectively. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Study Participants

| Eligible Participants |

Focus Group Participants |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total | 69 | 25 |

| Age (Mean, range) | 35.2 years (19-51) | 36.2 years (20-50) |

| Bleeding pattern (n, col%) | ||

| Heavy | 64 (93%) | 24 (96%) |

| Irregular | 67 (97%) | 24 (96%) |

| >8 days | 44 (64%) | 18 (72%) |

| Participants who reported having uterine fibroids or polyps causing bleeding |

26 (38%) | 8 (32%) |

| Participants who reported that their medications or other medical problems were the cause of their bleeding |

15 (22%) | 10 (40%) |

| Participants who reported both structural and systemic causes |

5 (7%) | 4 (17%) |

| Participants who did not report a known reason for their bleeding |

33(48%) | 10 (42%) |

Eligible women self-identified as having either heavy or irregular bleeding. Ninety-three percent of women who screened eligible for the study reported heavy bleeding, 97% reported irregular bleeding, and 64% reported bleeding episodes that lasted for longer than 8 days.

Perception of Bleeding Symptoms

Variability in perception of heavy bleeding

We asked women what makes a period “heavy” and obtained a variety of responses.

Some women related the “heaviness” of the menstrual period with how many pads or tampons they used and how often they needed to change their sanitary products. Examples of participants' responses were:

“There is ‘heavy’ that fills up pads and I have to change pads twice an hour and there's ‘heavy’ with blood clots that slide down my leg and ruins my clothes and shoes”.

“I use 3 to 4 pads at once and I still go through them”.

“They (my friends) can wear just a tampon for 2 or 3 hours before they change it. I can't wear a tampon until the fourth or fifth day (of my period) because I bleed so heavily I will go right through”.

For some women, “heavy” was determined by the quality of the bleeding, in terms of “gushes” and “clots”. Women described “It comes out in clots and gushes”. Another stated “I can't even visit anybody because I think I will sit down and leak right through. That's what's heavy to me. I sit there thinking ‘can I even cough’ and I sit to the side”. Women reported using towels and incontinence briefs to contain their bleeding. “Even to sit on my couch, I put a towel down just in case”.

Clinically, heavy menstrual bleeding is defined by increased volume of blood lost and duration of bleeding episodes. Five frequently used questions that pertained to the amount of bleeding experienced during menses were consistently viewed as important by focus group participants. (Table 2) Although all the women viewed the questions which addressed amount of bleeding as important, they stated that some “in-depth” questions also needed to be included. When asked what they meant by “in-depth”, they responded that their experiences with bleeding, such as having blood clots pass down their legs, were not truly captured with the questions included.

Table 2.

“Importance” of items from bleeding questionnaires, in the opinion of focus group participants. Listed by the concept to which the item referred (Row %, N)

| Very important |

Somewhat important |

Not important |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of bleeding | 76% (19) | 25% (6) | 0% (0) |

| Regular or irregular | 56% (14) | 44% (11) | 0% (0) |

| Cycle length | 48% (12) | 44% (11) | 8% (2) |

| Light, moderate, heavy, very heavy | 72% (18) | 28% (7) | 0% (0) |

| Number of heavy bleeding days | 79% (19) | 21% (5) | 0% (0) |

| Pain | 76% (19) | 25% (6)7 | 0% (0) |

| Soiling bedlinen and upholstery | 42% (10) | 29% (7) | 29% (7) |

| Work, housework, daily activities | 60% (15) | 25% (6) | 15% (4) |

| Confined to bed | 60% (15) | 25% (6) | 15% (4) |

| Leisure activities | 46% (11) | 42% (10) | 12% (3) |

| Sex life | 36% (9) | 36% (9) | 28% (7) |

| Number of pads | 75% (18) | 25% (6) | 0% (0) |

| Doubling up sanitary protection | 54% (13) | 46% (11) | 0% (0) |

All rows do not add up to n=25 because not all participants responded for every question.

Consistency in perception of irregular bleeding

Women generally used the word “unpredictable” when they referred to irregular menses. When asked about what “irregular periods” meant, one woman stated “Ít comes when it feels like it” and “One month it comes not at all, another month it comes three times during the month”. Women related that they always needed to carry sanitary products with them, and some discussed wearing a pad every day just in case they had bleeding. Irregularity, for these women, pertained to both not knowing when the menstrual period was going to start and when the menstrual period was going to end. “You never know when its going to come or when its going to stop”

Participants rated typical questions relating to cycle regularity as “important” but were divided as to whether they were “very important” or “somewhat important”. This is in contrast to the questions on volume and duration of bleeding, which were mostly viewed as “very important”. We attempted to determine whether women would prefer heavy but predictable menstrual periods or much lighter but unpredictable periods and women were fairly divided on their preferences.

Themes

In our analyses of experiences with heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding, five themes emerged: (1) irritation and inconvenience, (2) bleeding-associated pain, (3) self-consciousness about odor, (4) social embarrassment, and (5) ritual-like behavior.

Irritation and Inconvenience

Throughout the focus group sessions, women referred to their menstrual periods as “irritating” and “inconvenient”. Other words and phrases they used to describe their menses were, “Oh brother”, “Oh God not again”, “Disgusted”, and “Aargh”. Women also voiced that they were very frustrated by their periods with comments such as “My life will stop for a few days”.

Based on their statements and tone of voice, we determined that women were generally angry and upset by their menstrual periods. They reported that they avoided specific activities during their menses (such as exercising and social activities) and engaged in preparatory activities for their menses (organizing their work and social schedule, purchasing extra sanitary products). Women related their irritation and their extensive preparatory planning to the amount of bleeding they experienced and the absolute necessity of preventing embarrassing bleeding episodes.

Bleeding-associated pain

Women talked about how pain and cramping affected their lives when they had their menstrual period. “You get a pain when you feel the clot passing through you. It's like a labor pain”

In each of the focus group sessions, some participants voiced “pain” as the first thing that came to their mind when they thought about their period. Often, participants related the “heaviness” to the “cramping” and “pain”.

“(Healthcare providers) underestimate pain and even the bleeding, that too. I said to the nurse, you don't understand, the pain starts here (pointing to her back) and then it moves to my forward and I've given birth (in the alternative birthing center without anesthesia/analgesia) its not like I don't know (pain)….. I try to explain to her I can feel the clots just pushing out.”

In the opinions of focus group participants, the clinical question about pain was consistently rated as very important.

Self-consciousness about odor

Odor was an unanticipated emergent theme from the focus group sessions.

Odor spontaneously was mentioned by participants in three of the four focus group sessions. After one participant mentioned the subject of odor in a session, others discussed odor as well. It was communicated as a “self-consciousness” issue such that women were afraid about other people being offended by the way they smelled when they had their menstrual period. This was exhibited by the following quote from a participant: “I was in the car with my friend and I asked her to stop by my house because I had to go change my pad. I went back into the car after changing and my friend had a strange look on her face. Automatically, I thought ‘Oh my God, I stink’. It's a big concern with cleanliness and odor”.”

Social Embarrassment

Throughout all four focus groups, many participants provided examples of having suffered embarrassment because of their bleeding. A major theme to the open-ended questions was staining their clothes in public. In telling their stories, women used terms such as “embarrassed” and “worried”. Participants agreed with and supported other participants when they discussed these embarrassing episodes. During their accounts of these events, the other women listened attentively and nodded affirmatively. Most events involved staining clothes because of gushes of blood or blood clots while out in public as exemplified by the following participant quotes.

“I was at a wedding, and I had just come from the bathroom because I knew I had my period and needed to change my pad. I sat down and watched them dance, and before they were even finished dancing I stood up and looked to see I had messed up the nice lacy chair. I put the cloth napkin on and said ‘I'm leaving, this is so embarrassing’.”

“Well, I like to go fishing and my neighbor has a boat. When I'm on my period I don't go. I did once, I regretted it because I barely made it back on shore. I had to have a towel on the seat. It's like every time he hit the water with the boat, it just kept gushing.”

Several of the stories ended with a comment on how the participant would keep such an embarrassing episode from ever happening again. Although this was a major theme throughout all of the focus group sessions, a specific question (taken from the AMSS) that pertained to staining and soiling was not uniformly rated as very important. When asked about the following question from the AMSS “On average, during the last three months, have you had any problems with soiling/staining any of the following because of your periods” and were given the choices of outerclothing, bedlinen and upholstery, the women were roughly equally divided between those who felt the question was very important and those who felt it was not important at all. Superficially, this appeared to be an inconsistency between what women stated as their main concerns (about flooding and inability to contain their menstrual bleeding) and how they rated the specific question pertaining to soiling and staining. Because of this inconsistency, we asked women directly in the latter two focus group sessions why they repeatedly discussed episodes where they bled through their clothes but then responded that this particular question was not important.

One participant seemed to describe it best when she said, “That question (AMSS #7) is less important because I make sure I am prepared with pads and clothes”. This generated an additional theme and a possible explanation for this inconsistency, “ritual-like behavior”.

Ritual-like behavior

Participants' fear of social embarrassment resonated in many of their conversations surrounding “ritual-like behavior”. Women described specifically avoiding situations in which they could potentially be subjected to social embarrassment if they had bleeding which they could not contain. This was well illustrated by the following series of responses:

Moderator: “What activities would you do on a typical day that you did not have your period that you would never think of doing if you had your period?”

P1: “Shopping. Anything, really. Anything that's outside that would take a long period of time where you couldn't get to a bathroom.

P2: ” I cancelled my doctor's appointments just for that reason, cause I bleed through everything. I'm afraid of sitting there and going through my clothes.”

P3: ” Leaving your house, spending more time away from a bathroom…”

Women in all focus groups described very elaborate practices aimed at avoiding bleeding through clothes and onto sheets and furniture. Some women discussed having missed work because of their bleeding. “I would always call out (of work) or with any luck it would come on the weekend or my day off. But the first and second day (of my bleeding), it would be impossible to go to work. So it would be a day out of work every month.” More frequently, however, women shared that they still went to work and did their chores regardless of their bleeding. “I feel that most of this stuff (work, housework) I have to do regardless. It doesn't stop, I just got to get up and do it”.

Participants spoke about many different ways they contained and concealed bleeding when activities such as work could not be avoided with comments such as “My periods have been like this for so long that now I have a routine when it happens.” Some of the strategies included bringing bags full of commercially available sanitary products and extra clothes to work, making frequent trips to the bathroom to change products and assess bleeding, leaving work in the middle of a shift to change clothes, and making their own sanitary products with towels and incontinence briefs that had a better capacity to contain and conceal their bleeding.

Women discussed that although work was essential, they altered social plans because of their bleeding. “I have to come to work when I have my period. That's okay because I have access to a bathroom. I was supposed to go to into the city on a Saturday, but I couldn't go because if I don't have access to a bathroom, and then I'll be embarrassed by having blood all over my pants”. Other women consistently voiced that they avoided social activities. One participant stated, “It affects “even your social life- you can't have one”. Another woman stated “It's kind of hard to explain to someone if it happens at someone else's house. You're embarrassed and want to die - unless they are going through it (heavy bleeding) too”.

Participants felt like proximity to a bathroom in which they were comfortable largely controlled their engagement in social activities. One participant stated, “in the public bathroom I worry - Is it going to flush?”. Another woman recounted a typical interaction with her child when she had her period, “Mommy can't go there today. She has to stay close to the bathroom.”

DISCUSSION

We explored how women with heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding were affected by their symptoms. This study was conducted to increase the level of understanding of the experiences of women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Few qualitative studies have been conducted in the United States that focus specifically on how menstrual bleeding affects daily life. Using focus group sessions, we discovered five major themes that reflected women's experiences with bleeding and quality of life: (1) Irritation and inconvenience, (2) bleeding-associated pain, (3) self-consciousness about odor, (4) social embarrassment, and (5) ritual-like behavior. Employing a focus group format enhanced context and depth by encouraging participants to investigate ways that they were both similar to and different from one another.

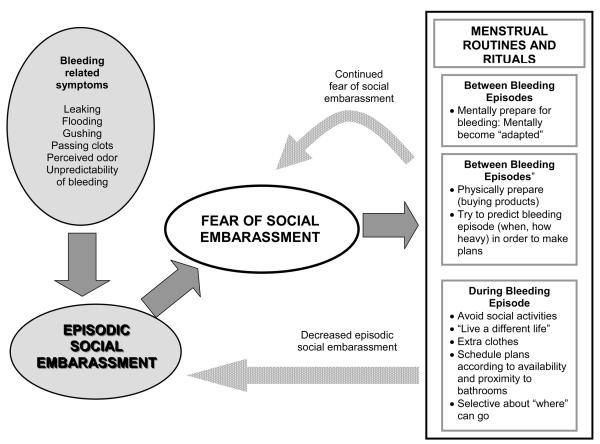

Based on these intimately interconnected themes, we developed a model for quality of life relative to heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding. (Figure 1) This model provides a framework that researchers and clinicians can use to more globally address the concerns of women who report heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding. The shaded areas represent concepts that are adequately covered with questions frequently asked during clinical assessments of women with heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding. The unshaded areas represent concepts that our data suggest are not adequately covered with the questions typically used in clinical encounters. In this model, women initially experience heavy or unpredictable bleeding which leads to bleeding through their clothes and social embarrassment. After these experiences, women become fearful about future episodes of social embarrassment and develop very specific routines for prevention of the embarrassment. These routines, which often involve avoiding any social plans and preparing with extra sanitary products and clothes, prevent socially embarrassing events but perpetuate their fear of social embarrassment. In our focus group sessions, women expressed that these two aspects of their lives, social embarrassment and alteration of activities to avoid social embarrassment, were dramatically affected by heavy menstrual bleeding and typical questions from available questionnaires covered these aspects in a manner that was too superficial to be meaningful. We believe that the focus group format facilitated the in-depth discussion of these aspects of women's lives most affected by AUB.

FIGURE 1.

A model for quality of life relative to heavy and/or irregular menstrual bleeding. Shaded—aspects of bleeding and life covered in typical questions used to clinically assess women with heavy and/or irregular menstrual bleeding. Unshaded—aspects of bleeding and life NOT adequately covered in typical questions used to clinically assess women with heavy and/or irregular menstrual bleeding.

Similar to other studies, we found that women felt that the heaviness of their bleeding and the numerous measures they took to conceal and contain their heavy menstrual bleeding significantly affected their lives (Santer et al., 2007; Santer et al., 2008, O'Flynn, 2006). Women were anxious and irritated about the inconvenience during their menstrual period and often rearranged their family, social, and work schedule to avoid episodes of embarrassment outside of their own home. In exploring “social embarrassment” we identified some inconsistencies both with previous studies and within our own study findings. In studies by Santer et al., women discussed “learning to cope” and avoiding out of home activities, but reported that social embarrassment was not a main concern (Santer et al., 2007; Santer et al., 2008). Women in our study noted social embarrassment was a main concern, but did not universally view a specific question on staining and soiling as important. (Ruta et al., 1995). At least two potential explanations are possible for these discrepancies. First, the discrepancies could support our finding that women adapt to their heavy menses. Or the discrepancies may reflect that the question, as written in the AMSS, was not adequately capturing our patients' experiences with social embarrassment.

Better assessing “patient experience” with heavy menstrual bleeding is important for improved clinical care and research. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic heavy menstrual bleeding are dependent upon what a woman says about her blood loss. Although many patient based outcome measures have been used in research, no one instrument is considered the “standard of care” for evaluating women with AUB in the clinical setting (Matteson et al., 2008). Because it is a “subjective experience”, and structured standardized evaluation tools are not used in clinical practice, aspects of speech are likely to influence which treatments, including hysterectomy, women are offered (Echlin et al., 2002). Consequently, physicians often have difficulty assessing women who report heavy menstrual bleeding. Some women may have difficulty articulating their symptoms and experiences with bleeding. As a result, these patients report more dissatisfaction with their interactions with healthcare providers (Garside et al., 2008; Marshall, 1998; O'Flynn and Britten, 2004). Our finding that women considered many of the questions asked frequently in a clinical encounters lacking in sufficient depth to be meaningful in terms of characterizing their clinical situation provides some insight into current difficulties assessing “patient” experience with heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding. Results from the focus group sessions provide information about the items that must be included in a structured assessment of women with these prevalent symptoms.

The study had several limitations. First, women were recruited only from healthcare settings. The opinions of this population may differ from women with heavy menstrual periods who do not seek care or who do not have access to healthcare, and these participants were likely to be at the more severe end of the spectrum of AUB and possibly of higher socioeconomic status than all women affected. Also, although the women who participated appeared to be representative of the larger population of eligible participants the observations were nonetheless obtained from a small, non-random, convenience sample, all of which limits the representativeness of the sample and thus the generalizability of the findings. To participate, women needed to feel comfortable discussing their menstrual periods with a group of other women. It is possible that women with more severe bleeding were more likely to want to participate in these focus group discussions to talk about their bleeding. In addition, the very low participation rate among eligible women was likely to have resulted in participation bias, further contributing to the lack of generalizability of the results obtained.

Some participants contacted the research team in response to flyers and posters describing the study. The women who were actively recruited for this study from the WPCC were “pre-screened”, meaning that the research assistant approached only women with abnormal uterine bleeding- associated complaints recorded in previous clinic visits or the reason for their current visit. Because of this, some eligible women may not have been offered participation in this study. Additionally, no data were collected on race-ethnicity or education status of the women who participated. In designing this study, we anticipated a small sample size for in-depth discussions and therefore did not plan to stratify the data based on demographic characteristics. Although we recruited from a diverse patient population with historically good participation rates in prospective studies, we do not have specific data on the race-ethnicity and education status of our participants. (Gutman et al., 2005) Data from this study were not meant to be generalized to a specific population, rather they were meant to generate in-depth information about women's experiences with heavy menstrual bleeding that could then be tested further in prospective studies. These limitations underscore the necessity of testing the identified themes in future prospective studies of diverse women with abnormal uterine bleeding.

Despite study limitations, our findings suggest that clinicians and researchers should broaden the discussions they have with patients who report heavy or irregular bleeding and consider asking more in-depth questions about patients' bleeding and pain. These discussions should go beyond discussing the actual bleeding to detail the behaviors women engage in to contain their bleeding and avoid embarrassing accidents. We would recommend asking whether women are passing blood clots, how often they go to the bathroom to assess their bleeding and change their menstrual products, and how much time it takes their bleeding to soak through a large menstrual pad. Additionally, women's experiences with and disruption in daily activities due to bleeding could be more comprehensively addressed by asking what women do to avoid embarrassment during their menstrual period, such as avoiding social activities altogether, planning activities based on bathroom availability, missing work, or preparing with spare clothes and packages of menstrual products. Facilitating healthcare providers' ability to assess symptoms and quality of life and enabling patients to better communicate their bleeding symptoms and concerns could lead to more meaningful patient provider interactions. To optimize this assessment of symptoms and quality of life, we need a standardized structured menstrual bleeding questionnaire to evaluate women who present for treatment of heavy or irregular menstrual periods.

This study identified themes which could inform the development of a standardized menstrual bleeding questionnaire which comprehensively evaluates “patient experience” with heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding. The process of developing such a standardized measurement tool should incorporate additional testing and refinement of the themes identified in this study, which can then aid with the development of individual questions. A standardized structured menstrual questionnaire could benefit medical care in several different ways. First, the use of a standard questionnaire could make clinical consultations more efficient because women could complete the questionnaire before the gynecologic consultation, by themselves or with the help of a medical assistant. Additionally, the questionnaire could be designed to be used at the initial and at follow-up consultation. Specific questions could be chosen to help practitioners, at the initial consultation, determine the most likely causes of the patients bleeding and thereby decide which treatments to try and which tests to order. If validated properly, such a questionnaire could potentially reduce ordering unnecessary medical tests and prescribing ineffective medical therapies. The questionnaire for the initial and follow-up consultations could also incorporate questions about the “patient experience” with bleeding which could allow practitioners to assess more easily the patient's response to treatment. Lastly, a standardized menstrual bleeding questionnaire could be used to meaningfully and consistently measure effectiveness of treatment, in terms of improving patient experience, in much needed future studies of treatment options for abnormal uterine bleeding.

CONCLUSIONS

The heaviness of bleeding is important to women with abnormal uterine bleeding. However, the behaviors women engage in to conceal and contain their bleeding so as to avoid social embarrassment are equally important and typically not adequately addressed by clinicians and researchers. Identifying the symptoms and situations that are most bothersome to women with heavy or irregular menstrual periods could help clinicians and researchers ask patients more meaningful questions and therefore improve both medical care and clinical research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF SUPPORT

This research is made possible through the National Institutes of Health-funded K12 - HD050108-02 WIH/Brown Women's Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) Grant

Footnotes

PRESENTATION AT CONFERENCE: This study was presented as poster presentation at the 17th Annual Congress of Women's Health, Williamsburg, VA, March 2009.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Drs. Matteson and Clark have no commercial associations that might create a conflict of interest. No competing financial interests exist.

REFERENCES

- Barnard K, Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM. Health status among women with menstrual symptoms. J Women's Health. 2003;12:911–9. doi: 10.1089/154099903770948140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TJ, Khan KS, Foon R, Pattison H, Bryan S, Gupta JK. Quality of life instruments in studies of menorrhagia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;104:96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote I, Jacobs P, Cumming D. Work loss associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:683–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote I, Jacobs P, Cumming DC. Use of health services associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States. Am Journal Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:343–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A, Peto V, Jenkinson C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life after treatment for menorrhagia. Family Practice. 1994;11:394–401. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echlin D, Garden AS, Salmon P. Listening to patients with unexplained menstrual symptoms: what do they tell the gynaecologist? BJOG. 2002;109:1335–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson J. Menarche, menstruation, and gender identity: Retrospective accounts from women who have undergone premenopausal hysterectomy. Sex Roles. 2002;46:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser IS, Critchley HOD, Munro MG, Broder M. A process designed to lead to international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:466–476. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garside R, Britten N, Stein K. The experience of heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63:550–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman RE, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Blume J. Evaluation of clinical methods for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:551–556. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000145752.97999.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L, Hogdahl AM, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss--a population study. Variation at different ages and attempts to define normality. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1966;45:320–51. doi: 10.3109/00016346609158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes P, Hodgson H, Anderson AB, Turnbull AC. Measurement of menstrual blood loss in patients complaining of menorrhagia. BJOG. 1977;84:763–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1977.tb12490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjerulff KH, Erickson BA, Langenberg PW. Chronic gynecological conditions reported by US women: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1984 to 1992. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:195–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisabeth L, Harlow S, Qaqish B. A new statistical approach demonstrated menstrual patterns during the menopausal transition did not vary by age at menopause. J Clin Epidemiology. 2004;57:484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, Dubois RW. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value in Health. 2007;10:173–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo Rogerio A. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: Ovulatory and anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding, management of acute and chronic excessive bleeding. In: Katz Vern L., Lentz Gretchen M., Lobo Rogerio A., Gershenson David M., editors. Comprehensive Gynecology. Mosby Elselvier; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 915–931. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. An exploration of women's concerns about heavy menstrual blood loss and their expectations regarding treatment. J Reprod Infant Psych. 1998;16:259–76. [Google Scholar]

- Matteson KA, Boardman LA, Munro MG, Clark MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a review of patient-based outcome measures. Fertil Steril. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.023. doi:10.1016/j.fertstert.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORI . Market Opinion and Research International. Research study conducted on behalf of Parke-Davis Laboratories; 1990. Women's Health in 1990. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline CG 44: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- O'Flynn N, Britten N. Menorrhagia in general practice--disease or illness. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flynn N, Britten N. Diagnosing menstrual disorders: a qualitative study of the approach of primary care professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:353–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flynn N. Menstrual Symptoms: The importance of social factors in women's experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:950–957. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Chadha YC, Flett GM, Hall MH, Russell IT. Assessment of patients with menorrhagia: how valid is a structured clinical history as a measure of health status? Qual Life Res. 1995;4:33–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00434381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer M, Warner P, Wyke S. A Scottish postal survey suggested that the prevailing clinical preoccupation with heavy periods does not reflect the epidemiology of reported symptoms and problems. J Clin Epidemiology. 2005;58:1206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer M, Wyke S, Warner P. What aspects of periods are most bothersome for women reporting heavy menstrual bleeding? Community survey and qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer M, Wyke S, Warner P. Women's management of menstrual symptoms: findings from a postal survey and qualitative interviews. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:276–88. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner PE, Critchley HO, Lumsden MA, Campbell-Brown M, Douglas A, Murray GD. Menorrhagia I: measured blood loss, clinical features, and outcome in women with heavy periods: a survey with follow-up data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.015. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]