Abstract

Determinants of urosepsis in Escherichia coli remain incompletely defined. Cyclomodulins (CMs) are a growing functional family of toxins that hijack the eukaryotic cell cycle. Four cyclomodulin types are actually known in E. coli: cytotoxic necrotizing factors (CNFs), cycle-inhibiting factor (Cif), cytolethal distending toxins (CDTs), and the pks-encoded toxin. In the present study, the distribution of CM-encoding genes and the functionality of these toxins were investigated in 197 E. coli strains isolated from patients with community-acquired urosepsis (n = 146) and from uninfected subjects (n = 51). This distribution was analyzed in relation to the phylogenetic background, clinical origin, and antibiotic resistance of the strains. It emerged from this study that strains harboring the pks island and the cnf1 gene (i) were strongly associated with the B2 phylogroup (P, <0.001), (ii) frequently harbored both toxin-encoded genes in phylogroup B2 (33%), and (iii) were predictive of a urosepsis origin (P, <0.001 to 0.005). However, the prevalences of the pks island among phylogroup B2 strains, in contrast to those of the cnf1 gene, were not significantly different between fecal and urosepsis groups, suggesting that the pks island is more important for the colonization process and the cnf1 gene for virulence. pks- or cnf1-harboring strains were significantly associated with susceptibility to antibiotics (amoxicillin, cotrimoxazole, and quinolones [P, <0.001 to 0.043]). Otherwise, only 6% and 1% of all strains harbored the cdtB and cif genes, respectively, with no particular distribution by phylogenetic background, antimicrobial susceptibility, or clinical origin.

The bacterial species Escherichia coli comprises a wide diversity of strains belonging to the commensal intestinal flora of humans and warm-blooded animals. Among these strains, several pathogenic variants cause intestinal or extraintestinal infections in humans and animals (33). Population genetic studies based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and various DNA markers (10, 20, 44) classify the E. coli strains into four major phylogenetic groups (A, B1, B2, and D). The groups are diversely associated with certain ecological niches and propensities to cause disease.

Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) strains are facultative pathogens that are not yet fully described. They are reported to belong mainly to phylogroups B2 and D, and they possess high numbers of virulence genes that belong to a flexible gene pool (43, 53). Among ExPEC strains, uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains take advantage of host behavior and susceptibility by employing virulence factors that facilitate bacterial growth and persistence in the urinary tract (5, 28-30). Important virulence mechanisms are adhesion, invasion, subversion of host defenses, and direct interference with host cellular functions via secreted effectors (33, 69).

These effectors include the cyclomodulins (CMs), a functional class of toxins that hijack the cell cycle, a fundamental host cell process (48). In the species E. coli, four kinds of CMs have been identified: the rho GTPase-targeting toxins CNF-1 to CNF-3 (cytotoxic necrotizing factors) (34), the cycle-inhibiting factor (Cif) (38), and two kinds of genotoxins, cytolethal distending toxins (CDTs) I to V (19) and the recently discovered colibactin (41). Colibactin is probably a hybrid polyketide-nonribosomal peptide toxin, whose activity is encoded by the genomic pks island (41). CDTs, Cif, and colibactin block mitosis, whereas CNFs promote DNA replication without cytokinesis. CM production can therefore be detected by the analysis of the cytopathic effects induced (41, 50).

E. coli CMs are encoded by mobile elements (genomic islands, plasmids, and bacteriophages) that belong to the flexible gene pool of E. coli (22). The aim of the present study was to compare the prevalences of CMs in E. coli strains that differed in their clinical origins (community-acquired urosepsis or feces), phylogroups, and susceptibilities to antimicrobial agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment of patients and strains.

One hundred forty-six E. coli strains were collected from blood cultures of 146 adults with community-acquired urosepsis between May 2006 and July 2008 in two university hospitals in France (Clermont-Ferrand [n = 86] and Rennes [n = 60]). Community-acquired urosepsis was defined as the association of a urinary tract infection (>104 leukocytes/ml and >105 CFU/ml) with bacteremia due to the same E. coli strain in patients who had not previously been admitted to hospital and whose hospital stay did not exceed 48 h. Patients with histories of urine disorders (previous hospitalization in a urology or nephrology unit, urethral instrumentation, or nephrostomy) were excluded. Of the 146 isolates, 123 came from samples taken in emergency wards, 5 in intensive care units, and 18 in other medical units. The median age of patients with urosepsis was 76 years (range, 20 to 96 years). There were 38 males (26%) (median age, 71 years; range, 22 to 93 years) and 108 females (74%) (median age, 76 years; range, 20 to 96 years).

Fecal isolates (n = 51) were collected by anal swabs from adults in the community who had no evidence of acute infection or other disorders of the gastrointestinal tract and who had not received antibiotics in the preceding month. The healthy individuals had no health care association within the past 6 months. Healthy individuals who had had urinary tract infections in the previous 12 months and patients with benign or malignant gastrointestinal disease were excluded. The median age of the 51 patients was 46.5 years (range, 23 to 62 years). There were 18 males (35%) (median age, 30.5 years; range, 24 to 59 years) and 33 females (65%) (median age, 50 years; range, 23 to 62 years). One arbitrarily selected E. coli colony per sample was analyzed. Previous data show that there is an 86% probability that an arbitrarily selected fecal E. coli colony represents the quantitatively predominant clone in the sample (35).

The E. coli strains were identified with the automated Vitek II system (bioMérieux). The experimental guidelines of the authors' institutions were followed in the conduct of clinical research. Epidemiological and laboratory results for each episode were recorded anonymously in a computer database in accordance with French law. E. coli archetypal reference strains and the E. coli K-12 strain DH5α, which are used as positive and negative controls, respectively, for genotypic and phenotypic analyses, are given in Table 1. All strains were stored on 15% glycerol-supplemented Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Archetypal E. coli control strains used in this study

| E. coli straina | Gene(s) or classification method | Host origin | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28C | hly, cnf1, cdt-IV, clbA,bclbK,bclbJ,bclbQb | Porcine septicemia | 13 |

| 1404 | cnf2, cdt-III | Bovine septicemia | 47 |

| IHE3034 ΔclbP | cdt-I, clb ΔclbP | Newborn meningitis | 41 |

| DH5α(pCP2123) | cdt-II | Laboratory strain | 54 |

| C48a | cnf3, eae, cifb | Healthy lamb | 45 |

| DH10β(pBACpks) | clb | Laboratory strain | 41 |

| E22 | cif, eae | Rabbit, EPEC | 38 |

| RS218 | PCR-based phylotyping | Newborn meningitis | 61 |

| EDL933 | eae, stx1, stx2 | EHEC | 51 |

| DH5α | Laboratory strain | Novagen |

Strain C48a was kindly provided by José Antonio Orden, and strain RS218 was kindly provided by Philippe Bidet and Edouard Bingen.

The clbA, clbK, clbJ, clbQ, and cif genes were detected during this study.

DNA extraction.

Template DNA was extracted by the boiling-water method. Briefly, three to five bacterial colonies from a freshly grown culture were suspended in 150 μl sterile distilled water and were incubated for 15 min at 95°C. After chilling on ice, bacterial debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh microcentrifuge tube and was stored at −20°C until required.

PCR phylogenetic grouping and fingerprint profiling.

E. coli strains were classified according to the Escherichia coli Reference Collection (ECOR) system (23) into phylogenetic groups A, B1, B2, and D by using a multiplex PCR technique (10). The uidA gene was used as an internal control of amplification, and the anonymous gene svg was detected to distinguish the B21 ribotyping/ST29 multilocus sequence type (MLST) isolates from the B2 strains (3). Three subtypes of phylogroup B2 strains were differentiated by this technique and were designated B21, Tsp-negative B2, and Tsp-positive B2. A DNA positive control was performed with strain RS218, which harbors all the genes targeted by the multiplex PCR. In order to investigate the clonal relationships among the pks- and cnf1-positive strains, fingerprint profiles had been generated for each isolate using the enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-PCR scheme reported by Adamus-Bialek et al. (1).

Detection of CM-producing genes by dot blot DNA hybridization.

CM-encoding genes were detected by dot blot DNA hybridization experiments. The probes were obtained by PCR with previously published primers (Table 2) by using the PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two-microgram DNA samples were fixed onto positively charged nylon membranes by UV illumination for 20 min. Hybridization was performed using the Roche labeling and detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) as indicated by the manufacturer. Each spot was checked with a 16S rRNA gene probe. The pks island, which contains the colibactin-producing gene cluster clb, was screened with a probe overlapping the clbK and clbJ genes. The cnf genes were detected with a mixture of probes specific to cnf1, cnf2, and cnf3. The cdtB genes were detected by two hybridization experiments with the cdtB-II-cdtB-III and cdtB-I-cdtB-IV probe mixtures. The cif gene was detected using an internal specific probe. The sensitivities and specificities of the probes were checked on each membrane by spotting DNA extracts of all CM control strains.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Tm of PCR (°C) | Specificity | PCR product size (bp) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91E | TCAAA(G,T)GAATTGACGGGGGC | 54 | 16S rRNA gene | 473 | 58 |

| 13B | GCCCGGGAACGTATTAC | 18 | |||

| pksORF9-10.1KJ | ATTCGATAGCGTCACCCAAC | 58 | clbK-clbJ | 2,119 | 41 |

| pksORF9-10.2KJ | TAAGCGTCTGGAATGCAGTG | ||||

| IHAPJPN42 | CAGATACACAGATACCATTCA | 55 | clbA | 1,002 | 27 |

| IHAPJPN46 | CTAGATTATCCGTGGCGATTC | ||||

| IHAPJPN55 | TTATCCTGTTAGCTTTCGTTC | 55 | clbQ | 821 | 27 |

| IHAPJPN56 | CTTGTATAGTTACACAACTATTTC | ||||

| CNF-1s | GGGGGAAGTACAGAAGAATTA | 48 | cnf1 | 1,112 | 64 |

| CNF-1as | TTGCCGTCCACTCTCACCAGT | ||||

| CNF-2s | TATCATACGGCAGGAGGAAGCACC | 48 | cnf2 | 1,241 | 66 |

| CNF-2as | GTCACAATAGACAATAATTTTCCG | ||||

| CNF3-3D | TAACGTAATTAGCAAAGA | 48 | cnf3 | 757 | 45 |

| CNF-3as | GTCTTCATTACTTACAGT | This study | |||

| CDT-s1 | GAAAGTAAATGGAATATAAATGTCCG | 60 | cdtB-II, cdtB-III, cdtB-V | 467 | 64 |

| CDT-as1 | AAATCACCAAGAATCATCCAGTTA | ||||

| CDT-IIasa | TTTGTGTTGCCGCCGCTGGTGAAA | 62 | cdtB-II | 556 | 64 |

| CDT-IIIasa | TTTGTGTCGGTGCAGCAGGGAAAA | 62 | cdtB-III, cdtB-V | 555 | 64 |

| CDT-s2 | GAAAATAAATGGAACACACATGTCCG | 56 | cdtB-I, cdtB-IV | 467 | 64 |

| CDT-as2 | AAATCTCCTGCAATCATCCAGTTA | ||||

| CDT-Is | CAATAGTCGCCCACAGGA | 56 | cdtB-I | 411 | 64 |

| CDT-Ias | ATAATCAAGAACACCACCAC | ||||

| CDT-IVs | CCTGATGGTTCAGGAGGCTGGTTC | 56 | cdtB-IV | 350 | 64 |

| CDT-IVas | TTGCTCCAGAATCTATACCT | ||||

| P105 | GTCAACGAACATTAGATTAT | 49 | cdtC-V | 748 | 25 |

| c2767r | ATGGTCATGCTTTGTTATAT | ||||

| cif-int-s | AACAGATGGCAACAGACTGG | 55 | cif | 383 | 38 |

| cif-int-as | AGTCAATGCTTTATGCGTCAT |

Used with primer CDT-s1.

Identification of the CM-producing genes and other virulence factors by PCR assays.

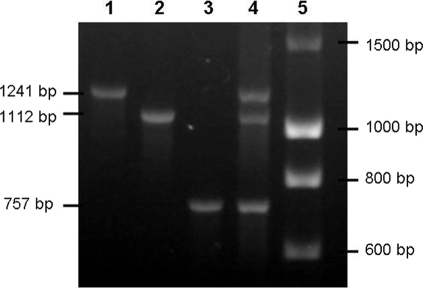

Positive hybridizations with a CM probe were subjected to confirmatory PCR assays using the primers given in Table 2. The reaction mixture contained 50 ng DNA sample, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.4 μM each primer, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1.0 U RedGoldStar DNA polymerase (Eurogentec, France) in the corresponding reaction buffer. Primers located in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the pks island (the clbA and clbQ genes) were used to confirm the full presence of the colibactin-producing island. A multiplex PCR was used to distinguish the cnf1, cnf2, and cnf3 genes. Figure 1 shows the standardization of the cnf multiplex PCR. cdtB-I, cdtB-II, cdtB-III/cdtB-V, and cdtB-IV were differentiated by simplex PCR. The cdt-III and cdt-V operons were differentiated by cdtC gene sequencing (Cogenics, Meylan, France) (Table 2) (4). Isolates harboring cdt or cif were further tested by PCR for the additional virulence factor genes stx1, stx2, and eae, as previously described (8).

FIG. 1.

Standardization of cnf gene typing by multiplex PCR. Lanes: 1, strain 1404 (cnf2); 2, strain 28C (cnf1); 3, strain C48a (cnf3); 4, mixture of equal quantities of 1404, 28c, and C48a DNAs (cnf1, cnf2, cnf3); 5, DNA ladder (Eurogentec).

Phenotypic tests.

The cytopathic effects of CNF and CDTs were investigated in all strains, and those of colibactin and Cif were investigated in nonhemolytic strains, as previously described (41, 50). Briefly, the effects of CDT and CNF were detected with a cell-lysate-interacting test. After a 48-h culture at 37°C with shaking in Luria-Bertani broth medium, bacterial cells were sonicated and were sterile filtered separately using 0.22-μm-pore-size filters. HeLa cells were treated with the sterile sonicated lysates until analysis. The effects of colibactin and Cif were detected using a cell-bacterium-interacting test, which was based on the interaction between HeLa cells and bacteria. Overnight Luria-Bertani broth cultures of E. coli were diluted in interaction medium, and HeLa cell cultures were infected at multiplicities of infection (numbers of bacteria per cell at the onset of infection) of 100 and 200. Cells were washed 3 to 6 times 4 h after inoculation and were incubated in cell culture medium with 200 μg/ml gentamicin until analysis. After 72 h of incubation at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the medium was removed by several washes of the HeLa cell monolayers. The morphological changes characteristic of CDT, CNF, colibactin, and Cif were observed after staining with Giemsa stain, as described elsewhere (41).

The detection of alpha-hemolysin was performed for all strains studied by overnight growth at 37°C on Columbia sheep blood (5%) agar (Oxoid, Dardilly, France). Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed by the disc diffusion method (Bio-Rad), using CA-SFM interpretative criteria (7). E. coli 25922 (ATCC) was used as the reference strain.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher exact and chi-square tests. (For multiple-group comparisons, an initial chi-square test for heterogeneity was done, and only if this yielded a P value of <0.05 were the individual pairwise comparisons tested.) The threshold for statistical significance was a P value of <0.05.

No statistical difference in the distribution of phylogenetic groups, CM genotypes, or antimicrobial resistance phenotypes was observed between strain groups of the same clinical origin from different geographic sources (except for resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins [C3G], where the P value was 0.041). The strains were therefore grouped together and were analyzed according to their uroseptic or fecal origin.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

E. coli phylogroups and clinical origin.

E. coli strains isolated from the fecal and urosepsis groups differed significantly in the prevalences of phylogenetic groups A, B1, and B2 but not in that of phylogroup D (Table 3). Phylogroup B2 was predominant in urosepsis strains (54%), followed by phylogroups D (23%), A (18%), and B1 (5%), as previously observed (5, 28-30). Fecal isolates belonged most frequently to phylogenetic group A (37%), followed by phylogroups B1 and B2, with identical prevalences (24%). These results are different from those of other studies, which found B2 strains predominant in fecal samples of healthy subjects, notably in industrialized countries (14, 16, 17, 29, 42, 71). This difference might be explained by the impact of geographic/climatic conditions, dietary factors, and/or the use of antibiotics or host genetic factors on the commensal flora (14, 16, 62). Hence, phylogroup A, and to a lesser extent phylogroup B1, was significantly more prevalent among fecal strains than among urosepsis strains (37% versus 18% [P, 0.011] and 24% versus 5% [P, <0.001], respectively). In contrast, phylogroup B2, known to encompass the most virulent ExPEC strains (15), was significantly more predominant in urosepsis strains than in fecal strains (54% versus 24% [P, <0.001]).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of phylogenetic groups among 197 E. coli isolates recovered from patients with urosepsis and from the feces of healthy individuals

| Phylogenetic group | No. (%) of E. coli isolates |

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal (n = 51) | Urosepsis (n = 146) | ||

| A | 19 (37) | 27 (18) | (0.011) |

| B1 | 12 (24) | 7 (5) | (<0.001) |

| B2 | 12 (24) | 79 (54) | <0.001 |

| D | 8 (16) | 33 (23) | |

P values (by Fisher's exact test) are shown where P is <0.05. P values given in parentheses indicate negative associations between the prevalence of the urosepsis strains and the particular phylogroup.

Distribution of CM-encoding genes according to phylogenetic background.

Table 4 shows a clear heterogeneity in the prevalences of CM genes, of which the most frequent were the pks island (27%) and cnf1 (18%), and in that of alpha-hemolysin expression (26%), three traits that were strongly associated with phylogroup B2.

TABLE 4.

Phylogenetic distribution of cyclomodulin genes and Hly among 197 E. coli isolates recovered from patients with urosepsis and from the feces of healthy individuals

| Virulence factor | No. (%) of E. coli isolates |

Pa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 197) | Group A (n = 46) | Group B1 (n = 19) | Group B2 (n = 91) | Group D (n = 41) | ||

| pks | 53 (27) | 0 | 0 | 53 (58) | 0 | <0.001 |

| cnf1-Hly | 36 (18) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 34 (37) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Hly alone | 15 (8) | 5 (11) | 0 | 8 (9) | 2 (5) | |

| cnf1-Hly, pks | 30 (15) | 0 | 0 | 30 (33) | 0 | <0.001 |

| cdtB-I | 5 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (4) | 0 | |

| cdtB-IV | 6 (3) | 0 | 0 | 5 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| cdtB-V | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| cif | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (11) | 0 | 0 | |

P values (by Fisher's exact test) are shown where P is <0.05 and are for comparisons of group B2 versus all other groups combined.

All pks-harboring strains belonged to phylogroup B2, as previously observed (27, 41, 56). This association was deep-seated (P, <0.001 for B2 versus A, B1, and D combined or separately). Fifty-eight percent of B2 strains possessed this trait, which was observed in all B2 subtypes according to phylogenetic grouping by PCR (3 among 12 B21 strains, 5 among 7 Tsp-negative B2 strains, and 45 among 75 Tsp-positive B2 strains).

Multiplex PCR-based cnf typing revealed only cnf1 genes. No cnf2 or cnf3 genes, which were first observed in E. coli strains isolated from animals (12, 45), were detected in our human strains, a finding consistent with the absence or very weak prevalence of these genes observed in previous studies (9, 12, 32, 37, 55, 63, 64). These results suggest that cnf2- and cnf3-positive strains are almost entirely absent in humans and thus are probably involved only in animal diseases. cnf1-harboring strains were highly associated with phylogroup B2, including 37% of E. coli B2 strains, but were barely present in the other phylogroups (P, <0.001 for B2 versus other groups), as previously observed (5, 26, 29, 30). Moreover, 33% of B2 strains harbored both the pks island and the cnf1 gene (P, <0.001 for B2 versus other groups), as previously observed (27).

All cnf1-positive strains exhibited the alpha-hemolytic phenotype. This association was probably due to the presence of the pathogenicity island (PAI) IIJ96-like domain, in which the cnf1 gene is located just downstream of the hlyCABD operon, which encodes the alpha-hemolytic phenotype (6, 34). We observed two isolates from one patient, one hemolytic cnf1-positive and one nonhemolytic cnf1-negative isolate, sharing the same randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) 1283 typing and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling, suggesting the spontaneous loss of a PAI IIJ96-like domain in the second isolate, as a result of the instability of the PAI (39). Only the hemolytic cnf1-positive isolate was retained for statistical analysis. Only 8% of strains exhibited an alpha-hemolytic phenotype without the cnf1 gene. These strains, which accounted for 29% of the alpha-hemolytic strains, had no particular phylogenetic distribution pattern. They probably possessed another PAI containing the hly operon, similar to the PAI ICFT073-like domain (21).

cdtB genes were observed in 6% of strains, with only one cdtB subtype per strain. Although 75% of cdtB-positive strains belonged to phylogroup B2, no significant phylogenetic distribution pattern clearly emerged, even among cdtB subtypes. In our study, cdtB-I (n = 5) and cdtB-IV (n = 6) types were overrepresented compared to the cdtB-V (n = 1) type. In contrast, no cdt-II- or cdt-III-positive strains were found. Of the cdt genes, cdt-I and cdt-IV are the most closely homologous, and both genes, framed with lambdoid prophage genes (65), might have been acquired from a common ancestor by phage transduction. cdt genes did not possess any particular association with the pks island or the cnf1 gene (see Table 6). Since cdt genes have been extensively investigated in Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) strains, cdt-harboring strains were screened for the eae and stx genes (4, 25, 46, 49). No eae or stx genes were detected in our cdt-encoding strains.

TABLE 6.

Distribution of phylogenetic group-cyclomodulin gene profiles among 197 E. coli isolates recovered from patients with urosepsis and from the feces of healthy individuals

| Phylogenetic group | CM gene profile | No. (%) of isolates |

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal (n = 51) | Urosepsis (n = 146) | |||

| B1 | None | 11 (21.6) | 4 (2.7) | (0.003) |

| cdtB-V | 1 (2) | 0 | ||

| cif | 0 | 2 (1.4) | ||

| cnf1 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | ||

| A | None | 18 (35.3) | 26 (17.8) | (0.018) |

| cnf1 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | ||

| cdtB-I | 1 (2) | 0 | ||

| B2 | None | 4 (7.8) | 26 (17.8) | |

| cnf1 | 0 | 4 (2.7) | ||

| pks | 4 (7.8) | 17 (11.6) | ||

| pks, cnf1 | 1 (2) | 26 (17.8) | 0.003 | |

| pks, cnf1, cdtB-I/cdtB-IVb | 0 | 3 (2) | ||

| pks, cdtB-I | 1 (2) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| cdtB-I/cdtB-IVb | 2 (4) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| D | None | 7 (13.7) | 33 (22.6) | |

| cdtB-IV | 1 (2) | 0 | ||

P values (by Fisher's exact test) are shown where P is <0.05. P values given in parentheses indicate negative associations between the prevalence of the urosepsis strains and the particular phylogenetic group-cyclomodulin gene profile.

Because of their small numbers, high level of homology, and close epidemiology, cdt-I and cdt-IV were aggregated.

Two cif-harboring strains were observed. They belonged to phylogroup B1 and harbored no other CM-encoding gene. Cif is an effector protein of the type 3 secretion system (T3SS) encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island, and previous observations of the cif gene were restricted to enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains (36, 38). The two cif-positive strains of this study were confirmed as EPEC strains by detection of the eae gene but not of stx genes.

Distribution of CM-encoding genes according to clinical origin.

Overall, the urosepsis strains had a significantly higher prevalence of the pks island than the fecal strains (32% versus 12%; P, 0.005) (Table 5). The pks island could therefore be involved in uropathogenesis; however, the prevalences of the pks island among phylogroup B2 strains were not significantly different between the fecal and urosepsis groups. The urosepsis strains were also significantly more likely to harbor Hly (P, <0.001) and cnf1 associated with Hly (P, <0.001) than the fecal strains. Likewise, the B2 urosepsis strains harbored cnf1 associated with Hly significantly more frequently than their B2 fecal counterparts (P, 0.028).

TABLE 5.

Distribution of cyclomodulin genes and Hly among 197 E. coli isolates according to phylogenetic group and clinical origin

| CM gene(s) | No. (%) of all isolates (n = 197) |

P value for all isolatesa | No. (%) of isolates |

P value for group B2a | No. (%) of group D isolates (n = 41) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 46) |

Group B1 (n = 19) |

Group B2 (n = 91) |

||||||||||

| Fecal (n = 51) | Urosepsis (n = 146) | Fecal (n = 19) | Urosepsis (n = 27) | Fecal (n = 12) | Urosepsis (n = 7) | Fecal (n = 12) | Urosepsis (n = 79) | Fecal (n = 8) | Urosepsis (n = 33) | |||

| pks | 6 (12) | 47 (32) | 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (50) | 47 (59) | 0 | 0 | |

| cnf1-Hly | 1 (2) | 35 (24) | <0.001 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 33 (42) | 0.028 | 0 | 0 |

| Hly alone | 3 (6) | 12 (8) | 2 (11) | 3 (11) | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 7 (9) | 0 | 2 (6) | ||

| cnf1-Hly, pks | 1 (2) | 29 (20) | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 29 (37) | 0 | 0 | |

| cdtB-I | 2 (4) | 3 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | ||

| cdtB-IV | 3 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (17) | 3 (4) | 1 (12) | 0 | ||

| cdtB-V | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| cif | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

P values (by Fisher's exact test) are shown where P is <0.05.

The weak prevalence of cdtB genes in urosepsis strains (4%) has been documented elsewhere (28, 29, 31). These observations suggest that CDTs are not major virulence factors for urosepsis. cdt genes in E. coli urosepsis strains were represented exclusively by the cdtB-I and cdtB-IV types. cdtB genes were more prevalent in the fecal isolates than in the urosepsis isolates (12% versus 4%), but not to the level of significance. This is in contrast with other studies in which cdtB prevalence in fecal strains ranged from 0.9% to 5%, with similar prevalences in urosepsis strains (29, 30, 32, 64). This difference may be explained in part by the exhaustive research into cdt subtypes that was performed in our study. In several studies, CDTs were detected in EPEC or STEC/EHEC strains isolated from patients with diarrhea (2, 4, 46, 49). Our CDT-producing strains were not isolated during bouts of enteric disease and did not possess eae or stx genes. A case-control study of CDT-producing E. coli showed no association between CDT-positive E. coli and diarrhea (2). Our cdtB-V-positive fecal strain did not possess stx and eae genes, while the cdtB-V gene has been reported only in STEC collections (4, 46). Finally, the two cif-positive, eae-positive urosepsis strains suggest the potential involvement of EPEC as an opportunistic organism in extraintestinal infections. The patients were both female and >80 years old, two risk factors for urinary sepsis.

Distribution of phylogroup-CM gene profiles according to clinical origin.

CM gene profiles and phylogroups were coanalyzed to determine whether combinations of CMs and phylogroups can also differentiate between the two clinical groups of strains (Table 6). Phylogroup B1 and A strains with no CM-encoding genes were significantly more prevalent in feces than in the blood cultures of patients with urosepsis (P, 0.003 and 0.018, respectively), whereas the association of the CM profile pks cnf1 with phylogroup B2 strains was more widespread in urosepsis strains (P, 0.003). Overall, both the pks island and the cnf1 gene, whether associated with another CM or not, were highly predictive of a urosepsis origin (20% versus 2%; P, 0.001) (Table 5). Three fingerprint profiles (encompassing 17, 10, and 3 strains) were obtained from the 30 pks-, cnf1-, and group B2-positive strains, suggesting that these urosepsis strains can belong to a distinct genetic background.

During urosepsis, colibactin and CNF1 may induce profound changes in cellular signaling pathways. Colibactin induces DNA double-strand breaks (41). CNF1 modulates a high number of cellular functions by hijacking rho GTPases (34), particularly attenuates polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions (11), and induces a severe and controlled inflammatory response (40, 57, 59, 60). By affecting the immune response, CNF1 could lengthen the brief time window between the establishment of bacteriuria and the activation of a host defense during urosepsis, consequently enhancing UPEC survival and allowing invasion of the parenchyma and bacteremia. CNF1 and probably colibactin may also favor host colonization, since their encoding genes have been found together in group B2 strains responsible for asymptomatic bacteriuria (70). In this study, the difference in the prevalences of the pks island and the cnf1 gene in B2 fecal strains suggest that colibactin may act mainly as a colonization factor and CNF-1 as a virulence factor (Table 5). Further experimental investigations are needed to shed light on the pathogenic and/or colonizer roles of these CMs.

Phenotypic detection of CMs.

Interpretation of the four CM-related phenotypes in eukaryotic cells was straightforward in all but two strains, which harbored the pks island and the cdt gene and for which the phenotypes are similar in the cell-bacterium-interacting test. Thus, we were not able to affirm that the pks islands of these two strains were functional. Nevertheless, all cdt- and cnf-positive strains produced a cytopathic effect, and a cytopathic effect induced by the pks island was observed in all but three strains. This result suggests nonfunctional pks islands. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other genes, potentially involved in the secretion of colibactin or in the synthesis of precursors used by pks island-encoded enzymes, were altered. It is noteworthy that two of these nonfunctional pks islands did not belong to ExPEC strains and accounted for 33% of pks-positive fecal isolates. Only one of the two cif genes produced a cytopathic effect. Loukiadis et al. reported that 66% of cif-positive E. coli strains did not induce a Cif-related phenotype in eukaryotic cells due to frameshift mutations or an insertion sequence in the cif gene (36). However, a nonfunctional T3SS may also explain the absence of a cytopathic effect. In addition, all strains that induced cytopathic effects harbored CM-encoding genes, suggesting that the genomic techniques used had reliable sensitivity.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of urosepsis strains according to CM-encoding genes and phylogenetic background.

The prevalence of antibiotic resistance among urosepsis strains was as follows: 59% were resistant to amoxicillin, 5% to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (C3G), 25% to cotrimoxazole, 18% to nalidixic acid and norfloxacin, 14% to ciprofloxacin, 2% to gentamicin, and 0% to amikacin. Table 7 shows the prevalences of CM-encoding genes and phylogenetic groups according to antibiotic susceptibility status. Quinolone susceptibility was associated with phylogenetic group B2 (59% of susceptible versus 33% of resistant isolates; P, 0.019) and the pks island (37% versus 11%; P, 0.011), whereas quinolone resistance was associated with group A (41% of resistant versus 13% of susceptible isolates; P, 0.002). Likewise, amoxicillin susceptibility was associated with group B2 (78% versus 37%; P, <0.001), the combination of the alpha-hemolytic phenotype and the cnf1 gene (35% versus 16%; P, 0.011), and the pks island (48% versus 21%; P, <0.001), whereas amoxicillin resistance was associated with groups A and D (28% versus 5% [P, <0.001] and 29% versus 13% [P, 0.028], respectively). Cotrimoxazole susceptibility was also associated with group B2 (60% versus 36%; P, 0.02), the alpha-hemolytic phenotype (36% versus 17%; P, 0.024), the combination of the alpha-hemolytic phenotype and the cnf1 gene (28% versus 11%; P, 0.043), and the pks island (41% versus 6%; P, <0.001). C3G susceptibility was associated with group B2 (57% versus 0%; P, 0.003), whereas C3G resistance (six strains with overexpression of chromosome-mediated cephalosporinases and one with an extended-spectrum β-lactamase, CTX-M-14) was associated with group A (86% versus 15%; P, <0.001).

TABLE 7.

Distribution of antibiotic susceptibility according to cyclomodulin genes/Hly and phylogenetic background among 143 E. coli isolates recovered from patients with urosepsisa

| Variable | Quinolones-fluoroquinolonesb |

Amoxicillin |

C3Gc |

Gentamicin |

Cotrimoxazole |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of isolates |

Pd | No. (%) of isolates |

Pd | No. (%) of isolates |

Pd | No. (%) of isolates |

No. (%) of isolates |

Pd | ||||||

| R (n = 27) | S (n = 119) | R (n = 86) | S (n = 60) | R (n = 7) | S (n = 139) | R (n = 3) | S (n = 143) | R (n = 36) | S (n = 110) | |||||

| Phylogenetic groups | ||||||||||||||

| A | 11 (41) | 16 (13) | (0.002) | 24 (28) | 3 (5) | (<0.001) | 6 (86) | 21 (15) | (<0.001) | 2 (67) | 25 (17) | 9 (25) | 18 (16) | |

| B1 | 2 (7) | 5 (4) | 5 (6) | 2 (3) | 1 (14) | 6 (4) | 1 (33) | 6 (4) | 3 (8) | 4 (4) | ||||

| B2 | 9 (33) | 70 (59) | 0.019 | 32 (37) | 47 (78) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 79 (57) | 0.003 | 0 (0) | 79 (55) | 13 (36) | 66 (60) | 0.020 |

| D | 5 (19) | 28 (24) | 25 (29) | 8 (13) | (0.028) | 0 (0) | 33 (24) | 0 (0) | 33 (23) | 11 (31) | 22 (20) | |||

| CMs | ||||||||||||||

| pks | 3 (11) | 44 (37) | 0.011 | 18 (21) | 29 (48) | <0.001 | 0 | 47 (34) | 0 | 47 (33) | 2 (6) | 45 (41) | <0.001 | |

| cnf1-Hly | 7 (26) | 28 (24) | 14 (16) | 21 (35) | 0.011 | 2 (29) | 33 (24) | 0 | 35 (24) | 4 (11) | 31 (28) | 0.043 | ||

| Hly alone | 1 (4) | 11 (9) | 8 (9) | 4 (7) | 0 | 12 (9) | 0 | 12 (8) | 2 (6) | 10 (9) | ||||

| cdtB-I | 0 | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 (3) | ||||

| cdtB-IV | 0 | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 (3) | ||||

| cif | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | ||||

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

All resistant isolates were resistant both to quinolone (nalidixic acid) and to fluoroquinolones (either norfloxacin alone or norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin).

C3G, extended-spectrum cephalosporins.

P values (by Fisher's exact test) are shown where P is <0.05. P values shown in parentheses indicate negative associations between the prevalence of the susceptible strains and the particular trait (phylogenetic group or CM).

These results suggest that resistance to quinolones is associated with the less virulent phylogenetic groups and with a weak prevalence of virulence factors, as previously observed (24, 26, 52, 67, 68). We obtained similar results for resistance against cotrimoxazole, amoxicillin, and C3G. The acquisition of antibiotic resistance by horizontal gene transfers or mutations may therefore require a particular genetic background, as observed for virulence factors (15). Some studies have suggested that the low-virulence group A isolates are more exposed to antibiotic selection pressure within the intestinal tract (24, 26), which indicates the possible importance of environmental factors.

Conclusion.

The distribution of CM-encoding genes, including the recently described pks genomic island, and the functionality of these toxins were investigated in E. coli strains in relation to their phylogenetic background, clinical origin, and antibiotic resistance. One finding to emerge from the present study was the frequent association of the pks island with the cnf1 gene and the alpha-hemolytic phenotype, and their presence in amoxicillin-, cotrimoxazole-, and quinolone-susceptible E. coli strains of the B2 phylogenetic background isolated from patients with urosepsis. The widespread diffusion of the pks island and the cnf1 gene in E. coli help to distinguish ExPEC from commensal strains and reinforce the idea that these genes of the E. coli flexible gene pool are involved in pathogenicity and/or in the ability to survive in new ecological niches, such as the human urinary tract.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by le Ministère Français de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (grant JE2526) and by l'Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (grant USC-2018).

We thank Rolande Perroux and Marlène Jan for helpful technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamus-Bialek, W., A. Wojtasik, M. Majchrzak, M. Sosnowski, and P. Parniewski. 2009. (CGG)4-based PCR as a novel tool for discrimination of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains: comparison with enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3937-3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert, M. J., S. M. Faruque, A. S. Faruque, K. A. Bettelheim, P. K. Neogi, N. A. Bhuiyan, and J. B. Kaper. 1996. Controlled study of cytolethal distending toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in Bangladeshi children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:717-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bidet, P., A. Metais, F. Mahjoub-Messai, L. Durand, M. Dehem, Y. Aujard, E. Bingen, X. Nassif, and S. Bonacorsi. 2007. Detection and identification by PCR of a highly virulent phylogenetic subgroup among extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli B2 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2373-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielaszewska, M., M. Fell, L. Greune, R. Prager, A. Fruth, H. Tschape, M. A. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 2004. Characterization of cytolethal distending toxin genes and expression in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains of non-O157 serogroups. Infect. Immun. 72:1812-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingen-Bidois, M., O. Clermont, S. Bonacorsi, M. Terki, N. Brahimi, C. Loukil, D. Barraud, and E. Bingen. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis and prevalence of urosepsis strains of Escherichia coli bearing pathogenicity island-like domains. Infect. Immun. 70:3216-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum, G., V. Falbo, A. Caprioli, and J. Hacker. 1995. Gene clusters encoding the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, Prs-fimbriae and alpha-hemolysin form the pathogenicity island II of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain J96. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 126:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CA-SFM. 2007. Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie, communiqué 2007. CA-SFM, Paris, France.

- 8.Chassagne, L., N. Pradel, F. Robin, V. Livrelli, R. Bonnet, and J. Delmas. 2009. Detection of stx1, stx2, and eae genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli using SYBR Green in a real-time polymerase chain reaction. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 64:98-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark, C. G., S. T. Johnson, R. H. Easy, J. L. Campbell, and F. G. Rodgers. 2002. PCR for detection of cdt-III and the relative frequencies of cytolethal distending toxin variant-producing Escherichia coli isolates from humans and cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2671-2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, J. M., H. M. Carvalho, S. B. Rasmussen, and A. D. O'Brien. 2006. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 delivered by outer membrane vesicles of uropathogenic Escherichia coli attenuates polymorphonuclear leukocyte antimicrobial activity and chemotaxis. Infect. Immun. 74:4401-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rycke, J., A. Milon, and E. Oswald. 1999. Necrotoxic Escherichia coli (NTEC): two emerging categories of human and animal pathogens. Vet. Res. 30:221-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dozois, C. M., S. Clement, C. Desautels, E. Oswald, and J. M. Fairbrother. 1997. Expression of P, S, and F1C adhesins by cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1-producing Escherichia coli from septicemic and diarrheic pigs. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duriez, P., O. Clermont, S. Bonacorsi, E. Bingen, A. Chaventre, J. Elion, B. Picard, and E. Denamur. 2001. Commensal Escherichia coli isolates are phylogenetically distributed among geographically distinct human populations. Microbiology 147:1671-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escobar-Páramo, P., O. Clermont, A. B. Blanc-Potard, H. Bui, C. Le Bouguenec, and E. Denamur. 2004. A specific genetic background is required for acquisition and expression of virulence factors in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21:1085-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escobar-Páramo, P., K. Grenet, A. Le Menac'h, L. Rode, E. Salgado, C. Amorin, S. Gouriou, B. Picard, M. C. Rahimy, A. Andremont, E. Denamur, and R. Ruimy. 2004. Large-scale population structure of human commensal Escherichia coli isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5698-5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escobar-Páramo, P., A. Le Menac'h, T. Le Gall, C. Amorin, S. Gouriou, B. Picard, D. Skurnik, and E. Denamur. 2006. Identification of forces shaping the commensal Escherichia coli genetic structure by comparing animal and human isolates. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1975-1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauduchon, V., L. Chalabreysse, J. Etienne, M. Celard, Y. Benito, H. Lepidi, F. Thivolet-Bejui, and F. Vandenesch. 2003. Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis by PCR amplification and direct sequencing of DNA from valve tissue. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:763-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge, Z., D. B. Schauer, and J. G. Fox. 2008. In vivo virulence properties of bacterial cytolethal-distending toxin. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1599-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon, D. M., O. Clermont, H. Tolley, and E. Denamur. 2008. Assigning Escherichia coli strains to phylogenetic groups: multi-locus sequence typing versus the PCR triplex method. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2484-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyer, D. M., J. S. Kao, and H. L. Mobley. 1998. Genomic analysis of a pathogenicity island in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: distribution of homologous sequences among isolates from patients with pyelonephritis, cystitis, and catheter-associated bacteriuria and from fecal samples. Infect. Immun. 66:4411-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker, J., U. Hentschel, and U. Dobrindt. 2003. Prokaryotic chromosomes and disease. Science 301:790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herzer, P. J., S. Inouye, M. Inouye, and T. S. Whittam. 1990. Phylogenetic distribution of branched RNA-linked multicopy single-stranded DNA among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:6175-6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houdouin, V., S. Bonacorsi, P. Bidet, M. Bingen-Bidois, D. Barraud, and E. Bingen. 2006. Phylogenetic background and carriage of pathogenicity island-like domains in relation to antibiotic resistance profiles among Escherichia coli urosepsis isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:748-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janka, A., M. Bielaszewska, U. Dobrindt, L. Greune, M. A. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 2003. Cytolethal distending toxin gene cluster in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H− and O157:H7: characterization and evolutionary considerations. Infect. Immun. 71:3634-3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauréguy, F., E. Carbonnelle, S. Bonacorsi, C. Clec'h, P. Casassus, E. Bingen, B. Picard, X. Nassif, and O. Lortholary. 2007. Host and bacterial determinants of initial severity and outcome of Escherichia coli sepsis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:854-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, J. R., B. Johnston, M. A. Kuskowski, J. P. Nougayrede, and E. Oswald. 2008. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic distribution of the Escherichia coli pks genomic island. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3906-3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, J. R., M. A. Kuskowski, A. Gajewski, S. Soto, J. P. Horcajada, M. T. Jimenez de Anta, and J. Vila. 2005. Extended virulence genotypes and phylogenetic background of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with cystitis, pyelonephritis, or prostatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 191:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, J. R., K. Owens, A. Gajewski, and M. A. Kuskowski. 2005. Bacterial characteristics in relation to clinical source of Escherichia coli isolates from women with acute cystitis or pyelonephritis and uninfected women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6064-6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, J. R., F. Scheutz, P. Ulleryd, M. A. Kuskowski, T. T. O'Bryan, and T. Sandberg. 2005. Host-pathogen relationships among Escherichia coli isolates recovered from men with febrile urinary tract infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:813-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadhum, H. J., D. Finlay, M. T. Rowe, I. G. Wilson, and H. J. Ball. 2008. Occurrence and characteristics of cytotoxic necrotizing factors, cytolethal distending toxins and other virulence factors in Escherichia coli from human blood and faecal samples. Epidemiol. Infect. 136:752-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemonnier, M., L. Landraud, and E. Lemichez. 2007. Rho GTPase-activating bacterial toxins: from bacterial virulence regulation to eukaryotic cell biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:515-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lidin-Janson, G., B. Kaijser, K. Lincoln, S. Olling, and H. Wedel. 1978. The homogeneity of the faecal coliform flora of normal school-girls, characterized by serological and biochemical properties. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 164:247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loukiadis, E., R. Nobe, S. Herold, C. Tramuta, Y. Ogura, T. Ooka, S. Morabito, M. Kerouredan, H. Brugere, H. Schmidt, T. Hayashi, and E. Oswald. 2008. Distribution, functional expression, and genetic organization of Cif, a phage-encoded type III-secreted effector from enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:275-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mainil, J. G., E. Jacquemin, and E. Oswald. 2003. Prevalence and identity of cdt-related sequences in necrotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Vet. Microbiol. 94:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marchès, O., T. N. Ledger, M. Boury, M. Ohara, X. Tu, F. Goffaux, J. Mainil, I. Rosenshine, M. Sugai, J. De Rycke, and E. Oswald. 2003. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli deliver a novel effector called Cif, which blocks cell cycle G2/M transition. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1553-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Middendorf, B., B. Hochhut, K. Leipold, U. Dobrindt, G. Blum-Oehler, and J. Hacker. 2004. Instability of pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli 536. J. Bacteriol. 186:3086-3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munro, P., G. Flatau, A. Doye, L. Boyer, O. Oregioni, J. L. Mege, L. Landraud, and E. Lemichez. 2004. Activation and proteasomal degradation of rho GTPases by cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1 elicit a controlled inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 279:35849-35857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nougayrède, J. P., S. Homburg, F. Taieb, M. Boury, E. Brzuszkiewicz, G. Gottschalk, C. Buchrieser, J. Hacker, U. Dobrindt, and E. Oswald. 2006. Escherichia coli induces DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells. Science 313:848-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowrouzian, F. L., I. Adlerberth, and A. E. Wold. 2006. Enhanced persistence in the colonic microbiota of Escherichia coli strains belonging to phylogenetic group B2: role of virulence factors and adherence to colonic cells. Microbes Infect. 8:834-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowrouzian, F. L., A. E. Wold, and I. Adlerberth. 2005. Escherichia coli strains belonging to phylogenetic group B2 have superior capacity to persist in the intestinal microflora of infants. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1078-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ochman, H., and R. K. Selander. 1984. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J. Bacteriol. 157:690-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orden, J. A., G. Dominguez-Bernal, S. Martinez-Pulgarin, M. Blanco, J. E. Blanco, A. Mora, J. Blanco, and R. de la Fuente. 2007. Necrotoxigenic Escherichia coli from sheep and goats produce a new type of cytotoxic necrotizing factor (CNF3) associated with the eae and ehxA genes. Int. Microbiol. 10:47-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orth, D., K. Grif, M. P. Dierich, and R. Wurzner. 2006. Cytolethal distending toxins in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: alleles, serotype distribution and biological effects. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:1487-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oswald, E., J. de Rycke, P. Lintermans, K. van Muylem, J. Mainil, G. Daube, and P. Pohl. 1991. Virulence factors associated with cytotoxic necrotizing factor type two in bovine diarrheic and septicemic strains of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2522-2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oswald, E., J. P. Nougayrède, F. Taieb, and M. Sugai. 2005. Bacterial toxins that modulate host cell-cycle progression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandey, M., A. Khan, S. C. Das, B. Sarkar, S. Kahali, S. Chakraborty, S. Chattopadhyay, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, G. B. Nair, and T. Ramamurthy. 2003. Association of cytolethal distending toxin locus cdtB with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from patients with acute diarrhea in Calcutta, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5277-5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pérès, S. Y., O. Marches, F. Daigle, J. P. Nougayrède, F. Herault, C. Tasca, J. De Rycke, and E. Oswald. 1997. A new cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) from Escherichia coli producing CNF2 blocks HeLa cell division in G2/M phase. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1095-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piatti, G., A. Mannini, M. Balistreri, and A. M. Schito. 2008. Virulence factors in urinary Escherichia coli strains: phylogenetic background and quinolone and fluoroquinolone resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:480-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Picard, B., J. S. Garcia, S. Gouriou, P. Duriez, N. Brahimi, E. Bingen, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1999. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect. Immun. 67:546-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pickett, C. L., D. L. Cottle, E. C. Pesci, and G. Bikah. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect. Immun. 62:1046-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pickett, C. L., R. B. Lee, A. Eyigor, B. Elitzur, E. M. Fox, and N. A. Strockbine. 2004. Patterns of variations in Escherichia coli strains that produce cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 72:684-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Putze, J., C. Hennequin, J. P. Nougayrède, W. Zhang, S. Homburg, H. Karch, M. A. Bringer, C. Fayolle, E. Carniel, W. Rabsch, T. A. Oelschlaeger, E. Oswald, C. Forestier, J. Hacker, and U. Dobrindt. 2009. Genetic structure and distribution of the colibactin genomic island among Enterobacteriaceae. Infect. Immun. 77:4696-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Real, J. M., P. Munro, C. Buisson-Touati, E. Lemichez, P. Boquet, and L. Landraud. 2007. Specificity of immunomodulator secretion in urinary samples in response to infection by alpha-hemolysin and CNF1 bearing uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cytokine 37:22-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Relman, D. A. 1993. The identification of uncultured microbial pathogens. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rippere-Lampe, K. E., M. Lang, H. Ceri, M. Olson, H. A. Lockman, and A. D. O'Brien. 2001. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1-positive Escherichia coli causes increased inflammation and tissue damage to the prostate in a rat prostatitis model. Infect. Immun. 69:6515-6519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rippere-Lampe, K. E., A. D. O'Brien, R. Conran, and H. A. Lockman. 2001. Mutation of the gene encoding cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (cnf1) attenuates the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 69:3954-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silver, R. P., W. Aaronson, A. Sutton, and R. Schneerson. 1980. Comparative analysis of plasmids and some metabolic characteristics of Escherichia coli K1 from diseased and healthy individuals. Infect. Immun. 29:200-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skurnik, D., D. Bonnet, C. Bernede-Bauduin, R. Michel, C. Guette, J. M. Becker, C. Balaire, F. Chau, J. Mohler, V. Jarlier, J. P. Boutin, B. Moreau, D. Guillemot, E. Denamur, A. Andremont, and R. Ruimy. 2008. Characteristics of human intestinal Escherichia coli with changing environments. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2132-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tavechio, A. T., L. R. Marques, C. M. Abe, and T. A. Gomes. 2004. Detection of cytotoxic necrotizing factor types 1 and 2 among fecal Escherichia coli isolates from Brazilian children with and without diarrhea. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tóth, I., F. Herault, L. Beutin, and E. Oswald. 2003. Production of cytolethal distending toxins by pathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from human and animal sources: establishment of the existence of a new cdt variant (type IV). J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4285-4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tóth, I., J. P. Nougayrède, U. Dobrindt, T. N. Ledger, M. Boury, S. Morabito, T. Fujiwara, M. Sugai, J. Hacker, and E. Oswald. 2009. Cytolethal distending toxin type I and type IV genes are framed with lambdoid prophage genes in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 77:492-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Bost, S., E. Jacquemin, E. Oswald, and J. Mainil. 2003. Multiplex PCRs for identification of necrotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4480-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Velasco, M., J. P. Horcajada, J. Mensa, A. Moreno-Martinez, J. Vila, J. A. Martinez, J. Ruiz, M. Barranco, G. Roig, and E. Soriano. 2001. Decreased invasive capacity of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli in patients with urinary tract infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1682-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vila, J., K. Simon, J. Ruiz, J. P. Horcajada, M. Velasco, M. Barranco, A. Moreno, and J. Mensa. 2002. Are quinolone-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli less virulent? J. Infect. Dis. 186:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiles, T. J., R. R. Kulesus, and M. A. Mulvey. 2008. Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 85:11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zdziarski, J., C. Svanborg, B. Wullt, J. Hacker, and U. Dobrindt. 2008. Molecular basis of commensalism in the urinary tract: low virulence or virulence attenuation? Infect. Immun. 76:695-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang, L., B. Foxman, and C. Marrs. 2002. Both urinary and rectal Escherichia coli isolates are dominated by strains of phylogenetic group B2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3951-3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]