Abstract

Tuberculosis is a common disease worldwide. However, it now is clear that tuberculosis can affect the kidney more insidiously. We describe a case of lumbar tuberculosis associated with simultaneous membranous nephropathy and interstitial nephritis, in which recovery of renal function occurred after treatment with steroids in addition to antituberculosis agents.

CASE REPORT

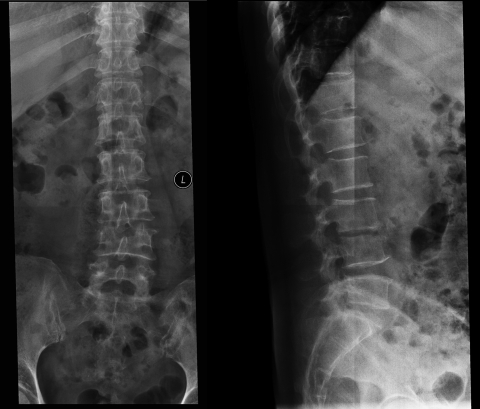

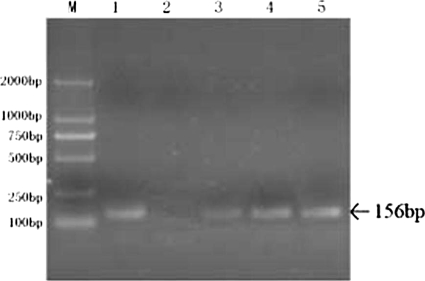

A 50-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a 2-week history of hematuria, proteinuria, and renal failure. She had been diagnosed with lumbar tuberculosis (TB) 6 weeks earlier because of mild fever, fatigue, night sweating, weight loss, and low-back pain. Her tuberculin skin test was strongly positive. A colloidal-gold-based serological assay with a Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibody assay kit (Assure TB Rapid Test; MP Biomedicals Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd., Singapore) was used to detect M. tuberculosis antibody. The result was positive. Lumbar X-ray examination showed that the L3-L4 disc space was narrow and destroyed (Fig. 1). She had been treated with rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 4 weeks before admission. Her temperature normalized, and the low-back pain disappeared. However, 2 weeks before the admission, she developed hematuria and proteinuria. Her serum creatinine, which had been 63 μmol/liter 1 month prior to presentation, rose to 183 μmol/liter. She reported no abnormal urinary frequency, dysuria, or flank pain. Her remaining medical history, travel history, and family history were unremarkable. Physical examination showed a body temperature of 36.8°C, a regular pulse rate of 85/min, respiratory rate of 18/min, and blood pressure of 140/85 mm Hg. Laboratory findings included a hemoglobin level of 9.3 g/dl, a platelet count of 320 × 109/liter, and a white cell count of 11.7 × 109/liter. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 24 mm/h, and C-reactive protein was 5.45 mg/dl. The blood urea nitrogen was 7.34 mmol/liter, and serum creatinine was 183 μmol/liter. Serum complement levels were normal. Urinalysis revealed 2+ protein, with 12 to 15 red blood cells and 16 to 20 white blood cells per high-power field (HPF) in the urinary sediment. Daily urinary protein excretion was 2.6 g. Complement 3 (C3) and C4 concentrations were normal. Serology for antinuclear antibody, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis was negative, and the patient was not otherwise immunocompromised. Sputum smears for acid-fast stain were negative. Chest X-ray examination was normal. Renal ultrasonography showed normal-size kidneys without any abnormality. PCR analysis using specific primers for M. tuberculosis was performed on early-morning urine samples for three consecutive days. DNA was extracted from the urine samples with the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers targeted to the specific insertion element insertion sequence (IS) IS6110 of M. tuberculosis were synthesized by Takara Bio Inc. (Dalian, China). The amplicon size was 156 bp. The results were positive (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Plain radiographs of the lumbar region showing that the L3-L4 disc space was narrow and destroyed. L indicates left.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR for TB DNA. M, DNA marker; lane 1, positive control; lane 2, negative control; lanes 3 to 5, urine samples on three consecutive days.

A morning urine sample was collected from the patient for M. tuberculosis culture. The urine sample was pretreated by decontamination with 4% (wt/vol) sodium hydroxide and centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min. The sediment was used for M. tuberculosis culture, which was performed using in-house Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) solid medium, with a maximum incubation period of 8 weeks. The result was read and reported weekly.

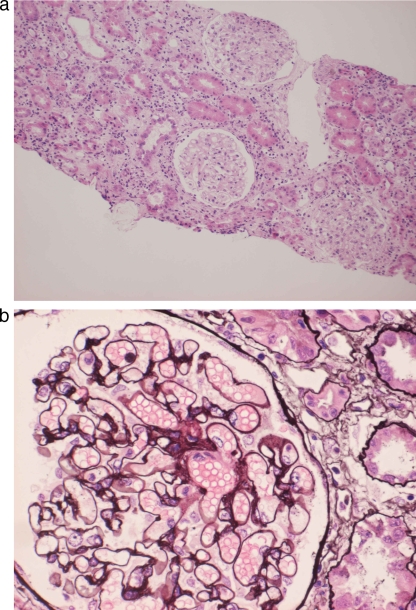

The patient had been treated with antituberculosis therapy for 4 weeks when she was admitted to the hospital. However, her renal function had deteriorated. To evaluate this, renal biopsy was performed a few days after admission. Pathological evaluation of the biopsied renal tissue showed membranous nephropathy with massive infiltration of inflammatory cells in the interstice (Fig. 3a and b). Immunofluorescence studies showed granular staining for IgG and C3 in the mesangium.

FIG. 3.

(a) Light microscopy finding of interstice showing massive inflammatory cell infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, ×100). (b) Light microscopy finding of a glomerulus showing glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening and small cystic spaces in the GBM (periodic acid-Schiff-methenamine staining; magnification, ×400).

Approximately 8 weeks later, urine culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative.

Because of the inflammatory pathological changes, a small dose of prednisone (30 mg/day) was added to the treatment, as well as the same antituberculosis agents mentioned above.

One month after the beginning of treatment with prednisone, the patient's serum creatinine decreased to 143 μmol/liter and 24-h urinary protein excretion was 1.6 g. Two months after the beginning of prednisone treatment, the serum creatinine decreased to 80 μmol/liter and the 24-h urinary protein excretion was 0.4 g. At that point, the daily dosage of prednisone was tapered by 5 mg per week. Six months later, her renal function remained normal and the urinalysis returned to normal (negative for protein, red blood cells [0 to 2/HPF], and white blood cells [0 to 5]/HPF). Both PCR analysis of M. tuberculosis on urine samples and urine M. tuberculosis culture were repeated 1 month, 2 months, and 6 months after steroid and antituberculosis medication during follow-up. The results were negative.

TB is still a common disease worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that one-third of the world's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is responsible for 8.7 million new TB cases and approximately 3 million deaths annually (13). Most often, the lung is affected, but after tuberculous lymphadenopathy, the next most common form of nonpulmonary tuberculosis is genitourinary disease, accounting for 27% of nonpulmonary TB cases in several surveys in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom (5).

Renal TB is easily overlooked. Many patients present with lower-urinary-tract symptoms typical of “conventional” bacterial cystitis, and suspicion of TB is aroused only when there is no response to the usual antibacterial agents or when urine examination reveals pyuria in the absence of a positive culture on routine culture media.

However, it now is clear that TB can affect the kidney more insidiously. Some patients present with glomerular disease, sometimes with advanced renal failure, instead of the features of classical renal TB (3, 4, 6, 8, 11).

This case clearly documents that TB infection can result in glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis simultaneously. It is well known that interstitial nephritis can result from many factors such as some antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, infection, idiopathic interstitial nephritis, and so on. In this case, no other suspectable drugs were used except the antituberculosis agents, which were not withdrawn during the prednisone therapy. And the patient's condition improved. This may indicate that interstitial nephritis is related to M. tuberculosis infection instead of being caused by other factors.

Moreover, primary membranous nephropathy is usually insensitive to steroid therapy. In this case, after the treatment of antituberculosis agents and a small dose of steroid, the 24-h urine protein excretion and serum creatinine improved significantly. Meanwhile, results of repeated PCR analysis on urine samples returned to negative during the follow-up.

Therefore, the medical history and histopathological findings, along with the therapeutic outcome, demonstrated that the glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions of this case were associated with M. tuberculosis infection.

The medical history and histopathological findings, along with the therapeutic outcome, leave no doubt as to this association.

M. tuberculosis can induce both cellular immune and humoral immune responses when the bacilli invade the body. Studies have shown that M. tuberculosis infection can lead to disturbances of Th1/Th2 cells, which may give rise to nephritis (9).

On the other hand, type III allergic reactions induced by immune complexes can cause tissue injury and may be involved in the pathogenesis of TB. The role of disseminated tuberculosis in the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis has been presumed to be dependent on humoral immunity, and immune complexes have been reported to be detectable at high levels in the active phase of disseminated tuberculosis (2, 12).

As a result, some patients have shown clinical features of chronic nephritis, such as hematuria, proteinuria, edema, and hypertension.

Meanwhile, TB infection can result in interstitial nephritis, which can lead to renal failure (7, 10). In some patients with pulmonary or disseminated tuberculosis, there is evidence of renal failure without typical miliary involvement or localized genitourinary lesions. In these cases, biopsy has shown interstitial nephritis usually, but not always, with granulomata and renal function has improved after antituberculosis treatment.

This case also demonstrates the value of renal biopsy in patients with glomerulonephritis or interstitial nephritis due to TB in the absence of radiological and urine findings. Diagnosis of renal TB remains difficult, especially in the early stage, due to the vagueness of chronic, intermittent, and nonspecific urinary symptoms. As a result, many patients are not diagnosed or are misdiagnosed, thereby losing the chance for early treatment and progressing to end-stage renal disease, a life-threatening condition. In our case, three urine cultures, considered the “gold standard” for diagnosis of renal TB (1), failed to show positive results. It may be because M. tuberculosis was intermittently evacuated, which made it difficult to detect in urine samples. Also, in the early stage of renal TB, renal radiologic examination usually does not show any abnormalities. Therefore, renal biopsy was performed in this patient. Although it did not show any typical granulomas, massive inflammatory cell infiltration of the glomeruli and nephric tubules was seen. When combined with the knowledge of the patient's clinical course and urine PCR result, these pathological changes suggested, and gave us potent support for, the diagnosis of TB-associated renal disease.

Finally, this case suggested the therapeutic option of using immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of renal tuberculosis. In most circumstances, TB-associated renal disease might respond to antimicrobial therapy alone and immunosuppressive agents would be unnecessary. However, in this case, there had been no improvement after 1 month of antituberculosis therapy with rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Therefore, 30 mg/day of prednisone was given to this patient because of the pathological changes showing massive inflammatory cell infiltration. One month after the beginning of antituberculosis agents and steroid treatment, improvement in renal function was noted and daily urinary protein excretion was decreased. This case indicates that steroids may be used as an adjunctive treatment of renal tuberculosis, particularly during the acute phase, based on the pathological results.

In conclusion, this case showed that glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis could simultaneously be associated with TB infection and that renal biopsy plays an important role on the diagnosis and treatment of renal tuberculosis. Although, in most circumstances, antituberculosis therapy alone will give satisfactory results, steroid treatment is still useful, and perhaps necessary, in some cases for improvement of renal disease.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. 2000. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161:1376-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatnagar, R., A. N. Malaviya, S. Narayanan, R. Premavathi, R. Kumar, and O. P. Bharadwaj. 1977. Spectrum of immune response abnormalities in different clinical forms of tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 115:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chugh, K. S. 1981. Pattern of renal amyloidosis in Indian patients. Postgrad. Med. J. 57:31-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coventry, S., and L. R. Shoemarker. 2004. Collapsing glomerulopathy in a 16-year-old girl with pulmonary tuberculosis: the role of systemic inflammatory mediators. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 7:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy, D. H. 1989. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, p. 245-284. In C. Ratledge, J. L. Stanford, and J. M. Grange (ed.), The biology of the mycobacteria, vol. III. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keven, K., F. A. Ulger, E. Oztas, I. Ergiin, Y. Ekmekci, A. Ensari, and K. Ates. 2004. A case of pulmonary tuberculosis associated with IgA nephropathy. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 8:1274-1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallinson, W. J. W., R. W. Fuller, D. A. Levison, L. R. I. Baker, and W. R. Cattell. 1981. Diffuse interstitial renal tuberculosis—an unusual cause of renal failure. Q. J. Med. 50:137-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzawa, N., K. Nakabayashi, T. Nagasawa, and Y. Nakamoto. 2002. Nephrotic IgA nephropathy associated with disseminated tuberculosis. Clin. Nephrol. 57:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rook, G. A., and R. Hernandez-Pando. 1994. T cell helper types and endocrines in the regulation of tissue-damaging mechanisms in tuberculosis. Immunobiology 191:478-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampathkumar, K., Y. S. Sooraj, A. R. Mahaldar, M. Ramakrishnan, A. Rajappannair, S. V. Nalumakkal, and E. Erode. 2009. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis due to tuberculosis—a rare presentation. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 20:842-845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shribman, J. H., J. B. Eastwood, and J. S. Uff. 1983. Immune-complex nephritis complicating miliary tuberculosis. Br. Med. J. 287:1593-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skvor, J., L. Trnka, and Z. Kugukovova. 1979. Immunoprofile studies in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand. J. Respir. Dis. 60:168-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van-Lume, D. S. M., J. R. de Souza, and W. G. Melo. 2008. Preliminary results in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis in children based on T cell responses to ESAT-6 and PPD antigens. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 103:401-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]