ABSTRACT

The face has functional and aesthetic importance. It represents the most identifiable aspect of an individual's physical being. Its role in a person's identity and ability to communicate can therefore not be overstated. The face also plays an important role in certain functional needs such as speech, communicative competence, eye protection, and emotional expressiveness. The latter function bears significant social and psychological import, because two thirds of our communication takes place through nonverbal facial expressions. Accordingly, the significance of reconstruction of the face is indisputable. Yet despite application of meticulous techniques and the development of innovative approaches, full functional and aesthetic reconstruction of the face remains challenging. This is because optimal reconstruction of specialized units of the face have to address both the functional and aesthetic roles of the face.

Keywords: Facial transplantation, allotransplantation, reconstructive surgery, bioethics

Traumatic deformities of the head and neck region resulting from burn injuries, gunshot wounds, or cancer-ablative surgeries create partial or full facial deformities. The aim of plastic surgery is to treat these deformities by reconstructive methods. To achieve satisfactory functional and aesthetic results, the texture, color, and pliability of the flap should be similar to the original tissue.1,2,3,4 Traditional reconstructive procedures in the head and neck region include combinations of skin grafting, local flaps, tissue expansion, prefabrication, and free tissue transfers.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 However, the cosmetic outcome of these creative surgical procedures has not proved satisfactory in long-term follow-up because they quite often result in a mask-like appearance that lacks normal facial movement and expression. Furthermore, the patients who undergo this surgery are often subjected to multiple procedures, the aim of which is to optimally improve the appearance and function of the face.1,3,15

FACIAL RECONSTRUCTION USING COMPOSITE TISSUE ALLOTRANSPLANTATION

The facial skin allograft is an example of composite tissue allotransplantation (CTA). Advances in the field of reconstructive surgery made the feasibility of CTA a clinical reality. Since the first hand transplant in France in 1998, 35 hand allograft transplants have been performed worldwide.16,17,18,19,20 More than 50 other CTA transplants have been performed worldwide; they include 9 abdominal wall transplants, 8 knees, 7 nerve allografts, 2 flexor tendon apparatus, 1 larynx, 1 skeletal muscle, 1 tongue, 1 penis, and 2 partial face transplants.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 Success in composite tissue allograft transplantation has led to routine applicability of these highly antigenic tissue transplants, including vascularized skin. After two recent partial face transplantations performed by French and Chinese surgical teams, the feasibility of allogeneic face transplantation has gained much public attention. It has been suggested that face allotransplantation could be a reconstructive alternative for patients with facial deformities that cannot be addressed through the application of currently available reconstructive procedures.30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39

TECHNICAL APPLICABILITY AND FEASIBILITY OF FACIAL/SCALP TRANSPLANTATION: OVERVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Reconstructive surgeons attempting to transplant facial allografts must address not only technical issues but also several other chiefly nontechnical issues, specifically (a) determining, feasibility, and applicability of face transplant; (b) developing protocols for lifelong immunosuppression; (c) discerning ethical, social, and psychological concerns; (d) obtaining institutional review board approval; (e) identifying appropriate recipients thorough a screening process based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria; and finally (f) finding appropriate donors.1,3,15

The vascular anatomy of the human face is well-known. The subcutaneous tissue contains rich vascular plexuses. The face is bilaterally supplied by the branches of the external carotid arteries, mainly the facial and superficial temporal arteries, and it is drained by the external jugular and facial veins. Accordingly, an entire facial skin flap based on the external carotid arteries could be transplanted.

One of the crucial issues that should be considered in facial transplantation, as with any microsurgical procedure, is the risk of flap failure. Vascular failure, diagnosed in the early stages of transplantation, can be treated by exploring the vascular pedicles and redoing the anastomoses. If all attempts to salvage the flap fail, the rescue procedure should be planned and defects should be covered with vascularized skin flaps or autologous skin grafts.1,3,15

Experimental studies on hemifacial and full facial allotransplantation in dog and rodent models have been successfully performed. Our cadaveric study revealed that after injection, methylene blue dye perfused skin and dermal plexuses of the flap and was well visualized from the external carotid artery up to the terminal branches of the facial and superficial temporal arteries.40

1. Scalp Transplantations

The only completely successful scalp transplantation to date was performed between identical twins41 without the need for immunosuppression. The twins were HLA identical and had identical blood groups. Mixed lymphocyte reaction was nonreactive. From her identical twin, the patient received two free scalp flaps measuring 19 cm × 3.5 cm and 17 cm × 3 cm, respectively, in two sessions. The flaps were based on superficial temporal arteries. At 6-month follow-up, without any immunosuppressive regimen, the flaps provided adequate hair growth. The second scalp transplant was more problematic. It was recently performed in a 72-year-old woman with stage IIIC recurrent cutaneous malignant melanoma on the vertex.42 Wide excision of the tumor including the scalp, facial/cervical skin, and two ears was performed. The defect was reconstructed by CTA, including scalp and both external ears, transplanted from a brain-dead young man. The patient received tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, steroids, and Zenapax (Daclizumab, Roche Pharmaceuticals) as an immunosuppressive protocol. A follow-up of 4 months was established. Regrettably, this transplant raises many technical, ethical, social, and legal concerns, for this elderly cancer patient was not a proper candidate for such extensive treatment, which required lifelong immunosuppression therapy.43

2. Scalp and/or Face Segment Replantations

Miller et al reported the first successful replantation of the entire scalp.44 Thereafter, replantations of many cases of partial or complete scalp avulsions were reported, including forehead, ear, eyebrow, and eyelid, with abundant regrowth of hair and return of scalp sensibility.45 Successful replantation of different avulsed segments of the face, including the nose, ear, and upper and lower lips, have also been reported.46,47,48

3. Total Face and Scalp Replantations

Although many cases of scalp and face segment replantation have been reported worldwide, only two successful cases of total face and scalp replantation have been reported.49,50 In the first, replantation was performed in two pieces, based on the medial canthal vein and the facial vein and artery on the right side, and the labial artery with its vein and superficial temporal artery and two concomitant veins on the left side. Three years after replantation, the patient recovered satisfactory animation of the oral musculature and profound growth of hair on the scalp.49 In the second case, the face was avulsed as one piece, including the entire scalp, right ear, forehead, eyebrows, right cheek, nose, and upper lip. This replantation was based only on a single superficial temporal artery and two veins. Four months postoperatively, the patient had hair growth and normal mimetic function.50

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS OF FACIAL/SCALP TRANSPLANTATION

During 2002–2006 in preparation for facial allograft transplantation in humans, we have developed full face and hemiface transplant models in rat to test different immunosuppressive protocols and tolerance induction across semi-allogeneic and full allogeneic histocompatibility barriers.51,52,53,54,55

1. Full Face/Scalp Transplant Model

We have confirmed the feasibility of total facial/scalp allograft transplantation across major histocompatibility (MHC) barriers in a rodent model for the first time. Transplants were performed between semi-allogenic LBN (RT11 + n) donors and Lewis (RT11) recipients. In the donors, based on the bilateral common carotid arteries and external jugular veins, the entire facial skin and scalp flap including both ears were harvested. In the recipient, the facial/scalp defect was created by excising facial skin, scalp, and external ears. The facial nerves and muscles, as well as the perioral and the periorbital regions were preserved to avoid functional deficits that could interfere with animal feeding, breathing, and eye closure. Both common carotid arteries were used to vascularize the full facial/scalp flap. Arterial anastomoses were performed to the common carotid arteries (end to side) or external carotid arteries (end to end) of the recipients. Venous anastomoses were performed to the external jugular and anterior facial veins (end to end). The recipient animals were treated with cyclosporin A (CsA) monotherapy in dose of 16 mg kg−1 day−1, which was tapered to 2 mg kg−1 day−1 over 4 weeks, and maintained at this level during the follow-up period of more than 200 days.51,52

2. Modifications of Full Face/Scalp Transplant Model

The full face/scalp transplant model is technically challenging and requires more than 6 hours to perform. To improve the survival of facial/scalp allograft recipients, two different modifications of the arterial anastomoses in the recipients were introduced. Unilateral common carotid artery of the recipient was used to vascularize the full transplanted facial/scalp flap. With these modifications, a bipedicled composite facial-scalp flap was vascularized by a single common carotid artery of the recipient, without dissecting the other common carotid artery. This modification decreased mortality tremendously by reducing cerebral ischemia time, bleeding, anesthesia time, and complications associated with bilateral common carotid artery dissection, such as vagus and phrenic nerve injuries in the recipients.53

3. Hemiface Transplant Model

To further reduce surgery time and brain ischemia time, we have introduced a hemifacial allograft transplant model that is technically less challenging compared with the full facial/scalp model. This model was used to test induction of operational tolerance across MHC barriers. Hemifacial allograft transplants were performed between semi-allogeneic Lewis-Brown-Norway (LBN RT11 + n) and fully allogeneic ACI (RT1a) donors and Lewis (RT11) recipients. Composite hemifacial/scalp flaps including the external ear and scalp, based on the common carotid artery and external jugular vein, were harvested from the donors. In the recipient, the hemifacial/scalp skin, including external ear, was excised. The arterial and venous anastomoses were performed to the common carotid artery (end-to-side) and to the external jugular vein (end to end), respectively. The same CsA monotherapy immunosuppressive protocol was used; and survival of 400 days was achieved for semi-allogeneic transplants and 330 days in the fully MHC-mismatched hemifacial transplant recipients54,55 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The hemifacial allograft transplantation model. (A) Preoperative view of the donor LBN rat showing markings of the facial skin flap. (B) Hemifacial-scalp flaps including the external ear and scalp, based on the common carotid artery and external jugular vein, were harvested from the donors. (C) Immediate posttransplant view of the hemiface allograft recipient. Transplantation was performed between semi-allogeneic LBN (RT11 + n) donors and Lewis (RT11) recipients. (D) The appearance of the semi-allogenic hemifacial allograft transplants under low dose CsA monotherapy at the 200th day after transplant shows no signs of rejection.

4. Composite Hemiface/Calvarium Transplantation Model in Rat

We have introduced a new composite hemiface/calvarium transplantation model in rat. The purpose of this composite tissue model was to extend application of the face/scalp transplantation model in rat by incorporation of the vascularized calvarial bone, based on the same vascular pedicle, as a new treatment option for extensive craniomaxillofacial deformities with large bone defects. Seven composite hemiface/calvarium transplantations were performed across the MHC barrier between Lewis-Brown-Norway (LBN, RT1l + n) and Lewis (RT11) rats. Hemicalvarial bone and face grafts were dissected on the same pedicle of common carotid artery and jugular vein and were transplanted to the de-epithelialized donor faces. All rats received tapered and continuous doses of CsA monotherapy. The average survival time was 154 days. No signs of rejection and no flap loss was noted at 220 days after transplantation. Bone histology at days 7, 30, 63, and 100 revealed posttransplants with viable bone at all time points; and computed tomography (CT) scans taken at days 14, 30, and 100 revealed normal bones without resorption. For the extensive face deformities involving large bone and soft tissue defects, this new osteomusculocutaneous hemiface/calvarium flap model may serve to create new reconstructive options for covering during one surgical procedure.56

5. Rat Maxilla Allotransplantation Model

We developed a rat model to test the effects of vascularized maxilla allotransplantation on composite maxillary substructures. Allograft maxilla transplantations were performed across the major histocompatability barrier between 10 Lewis-Brown-Norway (RT11 + n) and 10 Lewis (RT1l) recipient rats under CsA monotherapy. Grafts were dissected along Le-Fort II osteotomy lines based on common carotid artery and external jugular vein and transplanted to anterior abdominal wall via microvascular anastomosis. Allograft survived up to 105 days without signs of rejection. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated a high level of donor-specific chimerism in the peripheral blood . Histologic evaluation revealed remarkably intact structures, including teeth, toothbuds, toothpulp, bone, cartilage, oral mucosa, nasal mucosa, and soft palate musculature. We created a maxilla allotransplantation model that allows the study of immunologic responses and demonstrates potential clinical applications based on the growth properties of the allograft.57

6. Hemiface/Mandible-Tongue Flap Model

We introduced a new model of composite hemiface/mandible-tongue allograft transplant. A total of 12 composite hemiface/mandible-tongue transplantations were performed in two experimental groups. Group 1 isotransplantation between Lewis rats served as control without treatment (n = 6). Group 2 (n = 6) composite hemiface/mandible-tongue transplants were performed across the MHC barrier between Lewis-Brown-Norway (LBN, RT11 + n) donors and Lewis (RT11) recipients. Hemimandibular bone, masseter muscle, tongue, and hemifacial flaps were dissected on the same pedicle of external carotid artery and jugular vein and were transplanted to the donor inguinal region. All allogenic transplant recipients received 16 mg kg−1 day−1 of CsA monotherapy tapered to 2 mg kg−1 day−1 and maintained at this level thereafter. Isograft controls survived indefinitely. Six hemiface/mandible-tongue allotransplants survived up to 300 days (still under observation). No signs of rejection and no flap loss were noted. CT scan and bone histology confirmed viability of bone components of the composite allografts. Hematoxylin and eosin staining determined the presence of viable bone marrow cells within transplanted mandible. Donor-specific chimerism at day 100 posttransplant was evaluated through the presence of donor T cells (2.7% CD4/RT1n, 1.2% CD8/RT1n) and B cells (11.5% CD45RA/RT1n). Long-term allograft acceptance was accompanied by donor-specific chimerism supported by vascularized bone marrow transplant of the mandibular component. This model may serve as a new reconstructive option for coverage of the extensive head and neck deformities involving large bone and soft tissue defects.58,59

7. Large Animal Model: A Dog Model of Hemifacial Transplant

Thus far, there has been only one report on face transplantation performed in a large animal (dog) model. In 2002, Bermudez et al performed a hemifacial transplant between two dogs to prove the viability of a facial transplant using facial artery and external jugular vein as pedicles. The recipient dog received CsA and prednisone for immunosuppression to prevent hyperacute rejection of the allograft. The flap was acutely rejected by days 6 and 7 after transplantation, and the dog was euthanized. Thus, the authors proved that facial transplantation can be accomplished based on the facial artery and the external jugular vein as pedicles.56

CADAVERIC STUDIES

1. Search for Alternative Sources for Facial-Scalp Reconstruction

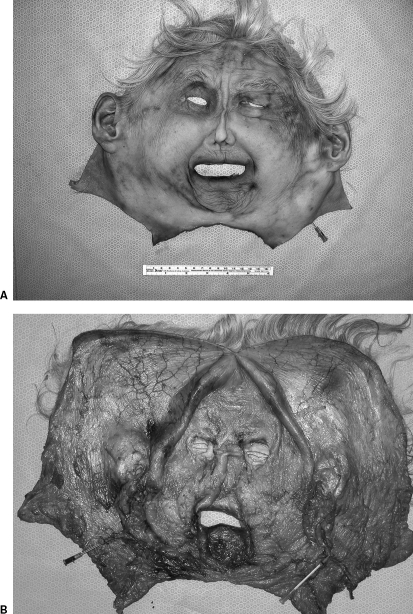

We have dissected cadavers to confirm the feasibility of facial flap harvest and to support the application of facial allograft transplants as a new treatment for patients with severe facial deformities. We compared the potential area of coverage, texture, and color match of these reconstructive options. In five cadavers, the composite full facial-scalp flap was designed to incorporate the entire facial skin, including the skin over the nose, eyelids, lips, both external ears, and the scalp. The whole flap was based bilaterally on the external carotid arteries as the arterial pedicles and on the external jugular and facial veins as the venous pedicles (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Harvested total facial-scalp flap. (A) The outer aspect of the harvested entire face and scalp flap including the external ears based on the external carotid arteries and external jugular veins. Methylene blue injection on the right side of the flap showed vascular territories. (B) Close view of the inner aspect of the facial-scalp flap (methylene blue injection on the right side of the flap shows vascular territories).

The conventional radial forearm, anterolateral thigh, bipedicled deep inferior epigastric, and bipedicled scapular-parascapular flaps were also harvested from the same cadavers. The total surface areas of the created facial defects and alternative harvested conventional flaps were measured. This cadaveric study confirmed that none of the conventional cutaneous autogenous flaps are able to cover total facial defects. It was found that the largest alternative conventional flap (bipedicle scapular-parascapular flap) covered only 50% of the total facial/scalp defect. We concluded that a perfect match of facial skin color, texture, and pliability could be achieved only by tissue of similar characteristics, which can be supplied by facial skin transplantation from the human cadaver donors.40

2. Mock Facial Transplantation

Recently, we performed a mock facial transplantation by harvesting a total facial-scalp flap from the donor and transferring the flap to the recipient cadavers. In the donor, we measured the time of facial-scalp flap harvesting and the length of the arterial and venous pedicles and sensory nerves, which were included in the facial flaps. In the recipient, we evaluated the time of facial skin harvest as a monobloc full-thickness graft, the anchoring regions for the inset of the donor facial flaps, and the time sequences for the vascular pedicles anastomoses and nerves coaptations. Based on anatomic dissections in this cadaver study, we have estimated the time and sequence of the facial flap harvest and inset to mimic the clinical scenario of the facial transplantation procedure.60

3. Evaluation of Identity Transfer After Mock Transplantation

Based on these cadaver studies, we have confirmed the technical feasibility of facial skin transplantation, and this has further encouraged us to address one of the most debatable issues after face transplantation, namely “identity transfer.” A total of 10 fresh human cadavers were dissected. In eight cadavers, the entire facial/scalp flap, including external ear components, was harvested. In two cadavers, to create a full facial defect, we harvested the facial skin as a monobloc full-thickness skin graft. These two cadavers served as the recipients of the donor facial flaps. Two different types of artificial head model, one made of glass and other made of Styrofoam, were used as the “recipients” for the harvested facial flaps. Three types of mock facial transplantations were performed. A series of digital photographs was taken to document transplant results. The facial appearance of the recipient cadavers after mock transplantation from different donor cadavers showed a mixture of features from both the recipient and the donor. The appearance of the facial flaps mounted on the head models was close to the “features” of the head models. When harvested facial flaps were transferred back into the original cadavers, the facial appearance was nearly the same as before transplant61 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of identity transfer after mock transplantation. (A) Appearance of the donor facial-scalp flap before harvesting. (B) When donor flap was harvested and mounted on the artificial head models serving as the recipients, the donor flap assumed the appearance of the recipient's head model.

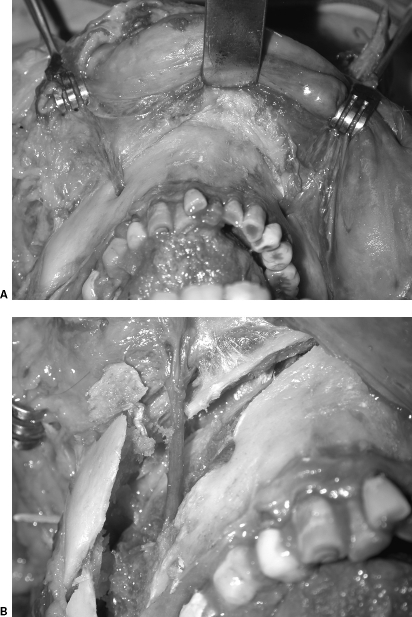

4. Coronal-Posterior Approach for Face/Scalp Flap Harvesting

We have developed a new technique, the coronal-posterior approach, for facial/scalp flap harvesting in the cadaver model to allow extended length to the neurovascular bundles utilized in facial composite allograft transplantation. In this study, 10 fresh human cadavers were dissected. The whole facial-scalp flap was harvested in five cadavers using the standard anterior approach and in five cadavers using the posterior-coronal approach. Supraorbital and infraorbital nerve lengths were extended by osteotomy of the cranial/orbital bone. The mental nerve lengths were extended into the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle utilizing a sagittal split ramus osteotomy. Using this coronal-posterior approach, we have gained extended length of sensory nerves within the facial flap; this approach will facilitate nerve coaptation and reduce surgery time for face transplantation62 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Coronal-posterior approach for face/scalp flap harvesting. (A) Appearance of the mental nerve before osteotomy. (B) The mental nerves' lengths were extended into the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle utilizing a sagittal split ramus osteotomy.

RECENT PARTIAL FACE TRANSPLANTS

On November 27, 2005, a French team led by Dr. Jean-Michel Dubernard performed the world's first partial face transplant using the nose, lips, and chin from a brain-dead living donor to repair the face of a 38-year-old woman who had been bitten by a dog. One week after surgery, the patient was able to eat and drink. Besides the immunosuppressive protocol (Thymoglobulin, Genzyme Corporation, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone), injection of stem cells from the donor's bone marrow was given to help prevent tissue rejection. Although surgeons were pleased with the patient's progress after face transplant, whether or not this operation opens a new frontier in reconstructive surgery will depend on the long-term clinical outcome.30,31,32,33,35

In April 2006, a Chinese surgery team led by Dr. Guo Shuzhong performed the world's second partial face transplant. The patient, a 30-year-old farmer, was severely disfigured when he was mauled by a black bear in 2004. The upper lip was missing, all the upper teeth were exposed, and the patient had also lost the front wall of his maxillary sinus as well as part of his cheekbone, leaving him prone to infections. From the donor, the surgical team removed the entire nose, upper lip, some soft tissue from the left side of the face, and more than two thirds from the right side, including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle along with bone from the nose and malar area. The major difference between the French case and the Chinese case was that the Chinese surgical team included bone and salivary gland tissue in the partial face transplant.34,35

PSYCHOLOGICAL, SOCIAL, AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS OF FACIAL TRANSPLANTATION

The recent success in CTA transplantation has made facial allograft transplantation a new option for patients with severe facial disfigurements. Nevertheless, face allograft transplantation from the human donor has given rise to ethical, social, and psychological controversies within the medical community. The current consensus is that potential candidates for this surgery should be evaluated only by a team of experts from different specialties. This multidisciplinary team should include plastic surgeons, transplant surgeons, immunologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, infectious disease specialists, ethicists, patient advocates, social workers, lawyers for the medical community, public relations experts, and representatives of the media.3,15,37,38,39,63

Moreover, because face transplantation would require lifelong immunosuppression, which exposes the recipients to significant life-threatening complications and uncertain benefits, the question has been raised of whether or not surgeons should nevertheless proceed.37 Agich and Siemionow have emphasized that patients with severe facial deformities should reserve the right to improve their quality of life and should therefore be included in any discussions or decisions regarding facial transplantation.64 In 2004, the French National Ethics Advisory Committee concluded that it was too early to approve facial transplants from cadaveric donors. The committee rejected the application of plastic surgeons led by Dr. Laurent Lantieri to perform full facial transplantation. They concluded that transplantation of the entire face is not at present feasible, and that even surgery on facial subunits such as the nose and mouth area is highly risky. Nevertheless, on November 27, 2005, the first partial face transplantation was performed with the approval of the committee.3,15,35,38,65

In sum, organ transplantation may induce a set of stresses and psychosocial problems.66 These fears and anxieties would likely be exacerbated in the case of facial transplantation because of such issues as identity and communication, psychological vulnerability, expectations of outcome, consequences of transplant failure, adherence to treatment regimens, and encounters with the reactions of others to altered appearance.39 On October 15, 2004, after 10 months of debate on the medical, ethical, and psychological issues related to facial transplantation, the Cleveland Clinic's Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the first protocol for facial transplantation presented by Dr. Maria Siemionow. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening potential candidates for facial transplantation were thoroughly evaluated. The donor and recipient consent forms have been approved. IRB approval allowed us to open the Facial Transplantation Program, where teams of specialists, including surgeons, psychologists, psychiatrists, ethicists, patient advocates, and media representatives will evaluate patients with severe facial deformities. Based on this evaluation, the most appropriate candidates for facial transplantation will be selected. Recent reports updating the outcome of the first partial face transplantation in France have brought to light concerns stemming from the animosity of donors, as well as compliance of the recipient, and side effects of immunosuppression.35

The question thus remains whether potential donors and the their families would ever accept full facial skin donation. At this point, we are not sure how close we are to being allowed to implement all of our innovations; nor can we know how long it will take for the first full facial transplantation to be performed.15

CONCLUSION

Facial allograft transplantation would revolutionize the field of transplantation and reconstructive surgery. At this stage, we have substantial anatomic knowledge, microsurgical skills, and immunologic expertise to make facial transplantation a clinical reality. The two recent cases of partial face transplantation confirm the feasibility of the procedure, but they also attest to the risk of rejection and to the side effects of immunosuppression. Therefore, before we proceed with routine application of face transplantation, we must weigh the risks versus the benefits of lifelong immunosuppression and on a case-by-case basis openly discuss the ethical and psychological factors with potential candidates. Patients living with severe facial deformities might well be willing to assume the risks of allograft transplantation to have the chance to recover a more normal appearance. Patients with severe facial disfigurements should be informed about all available reconstructive options, including facial allograft transplantation.

REFERENCES

- Siemionow M, Agaoglu G. In: Siemionow MZ, editor. Tissue Surgery. London: Springer-Verlag; 2006. Perspectives for facial allograft transplantation in humans. pp. 119–134.

- Rohrich R J, Longaker M T, Cunningham B. On the ethics of composite tissue allotransplantation (facial transplantation) Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2071–2073. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201309.72162.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Ozmen S, Demir Y. Prospects for facial allograft transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;15:1421–1428. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000112792.44312.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallua N, von Heimburg D. Pre-expanded ultra-thin supraclavicular flaps for (full-) face reconstruction with reduced donor-site morbidity and without the need for microsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1837–1844. discussion 1845–1847. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000165080.70891.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol O O. The transformation of a free skin graft into a vascularized pedicled flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:470–477. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197610000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri R K, Upton J, Shaw W W. Prefabrication of composite free flaps through staged microvascular transfer: an experimental and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:108–115. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribaz J J, Fine N A. Prelamination: defining the prefabricated flap: a case report and review. Microsurgery. 1994;15:618–623. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920150903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatopoulos C, Panayotou P, Tsirigotou S, et al. Use of free flaps in the aesthetic reconstruction of face and neck deformities. Microsurgery. 1992;13:188–191. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzon W M, Jr, Jejurikar S, Wilkins E G, et al. Double free-flap reconstruction of massive defects involving the lip, chin, and mandible. Microsurgery. 1998;18:372–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1998)18:6<372::aid-micr6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serletti J M, Tavin E, Moran S L, et al. Total lower lip reconstruction with a sensate composite radial forearm-palmaris longus free flap and a tongue flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:559–561. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199702000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menick F J. Facial reconstruction with local and distant tissue: the interface of aesthetic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1424–1433. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199810000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgfeld C B, Low D W. Total face reconstruction using a pre-expanded, bilateral, extended, parascapular free flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:565–568. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000210626.64620.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Takeuchi M, Fujiwara O, et al. Total face reconstruction with one expanded free flap. Surg Technol Int. 2005;14:329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrigiani C, Grilli D. Total face reconstruction with one free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1566–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Agaoglu G. Allotransplantation of the face: how close are we? Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetta M, Petruzzo P, Dubernard J M, et al. Second Report (1998–2006) of the International Registry of Hand and Composite Tissue Transplantation. Transplant Immunology. 2007;18:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit F, Minns A B, Dubernard J M, et al. Composite tissue allotransplantation and reconstructive surgery: first clinical applications. Ann Surg. 2003;237:19–25. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cendales L C, Breidenbach W C., 3rd Hand Transplantation. Hand Clin. 2001;17:499–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J W, Gruber S A, Barker J H, et al. Successful hand transplantation. One-year follow-up. Louisville Hand Transplant Team. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:468–473. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois C G, Breidenbach W C, Maldonado C, et al. Hand transplantation: comparisons and observations of the first four clinical cases. Microsurgery. 2000;20:360–371. doi: 10.1002/1098-2752(2000)20:8<360::aid-micr4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D M, Tzakis A G, Kato T, et al. Transplantation of the abdominal wall. Lancet. 2003;361:2173–2176. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann G O, Kirschner M H, Wagner F D, et al. Allogeneic vascularized transplantation of human femoral diaphyses and total knee joints—first clinical experiences. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2754–2761. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00803-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome M, Stein I, Esclamado R, et al. Laryngeal transplantation and 40-month follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1676–1679. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimberteau J C, Baudet I, Panconi B, et al. Human allotransplant of a digital flexion system vascularized on the ulnar pedicle: a preliminary report and 1-year follow up of two cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1135–1147. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199206000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T R, Humphrey P A, Brennan D C. Transplantation of vascularized allogeneic skeletal muscle for scalp reconstruction in renal transplant patient. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2746–2753. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00802-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon S E, Doolabh V B, Novak C B, et al. Clinical outcome following nerve allograft transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1419–1429. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiaratchy S, Randolph M A, Petit F, et al. Composite tissue allotransplantation—a new era in plastic surgery? Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:381–39l. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchall M. Tongue transplantation. Lancet. 2004;363:1663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Lu J, Zhang L, et al. A preliminary report of penile transplantation. Eur Urol. 2006;50:851–853. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman L K. French, in first, use a transplant to repair a face. New York Times: December 1, 2005. [PubMed]

- Butler P E, Clarke A, Hettiaratchy S. Facial transplantation. BMJ. 2005;331:1349–1350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7529.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The first facial transplant. Lancet. 2005;366:1984. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67795-1. [Editorial] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurgeon B. Surgeons pleased with patient's progress after face transplant. BMJ. 2005;331:1359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesitus J. Chinese transplant surgery. Cosmetic Surgery Times. 2006;9:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Devauchelle B, Badet L, Lengele B, et al. First human face allograft: early report. Lancet. 2006;368:203–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiaratchy S, Butler P E. Face transplantation: fantasy or the future? Lancet. 2002;360:5–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler P EM, Clarke A, Aschcroft R E. Face transplantation: when and for whom? Am J Bioeth. 2004;4:16–17. doi: 10.1080/15265160490496589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins O P, Barker J H, Martinez S, et al. On the ethics of facial transplantation research. Am J Bioeth. 2004;4:1–12. doi: 10.1080/15265160490496507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P J, Bradley J A, Doyal L, et al. Facial transplantation: a working party report from the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Transplantation. 2004;77:330–338. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000113810.54865.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Unal S, Agaoglu G, et al. A cadaver study in preparation for facial allograft transplantation in humans: part I. What are alternative sources for total facial defect coverage? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:864–872. discussion 873–875. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000204875.10333.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buncke H J, Hoffman W Y, Alpert B S, et al. Microvascular transplant of two free scalp flaps between identical twins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:605–609. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H Q, Wang Y, Hu X B, et al. Composite tissue allograft transplantation of cephalocervical skin flap and two ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:31e–35e. discussion 36e–37e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000153038.31865.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Agaoglu G. Controversies following the report on transplantation of cephalocervical skin flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:268–270. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222222.18263.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G D, Auster E J, Shell J A. Successful replantation of an avulsed scalp by microsurgical anastomoses. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:133–136. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K, Zhou S, Jiang K, et al. Microsurgical replantation of the avulsed scalp: report of 20 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1099–1106. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D C, Bouwense C, Hankins W T, et al. Microsurgical replantation of the amputated nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2133–2136. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200005000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon M J, Puckett C L. Microsurgical replantation of an ear in a child without venous repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2088–2093. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199811000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng S F, Wei P C, Noordhoff M S. Successful replantation of a bitten-off vermilion of the lower lip by microvascular anastomosis: case report. J Trauma. 1992;33:914–916. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199212000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Obed V, Murarka A, et al. Total face and scalp replantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2085–2087. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199811000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmi B J, Kang R H, Movassaghi K, et al. First successful replantation of face and scalp with single-artery repair: model for face and scalp transplantation. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:535–540. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000037875.69379.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Gozel-Ulusal B, Ulusal A, et al. Functional tolerance following face transplantation in the rat. Transplantation. 2003;75:1607–1609. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000068870.71053.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulusal B G, Ulusal A E, Ozmen S, et al. A new composite facial and scalp transplantation model in rats. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1302–1311. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000079823.84984.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal S, Agaoglu G, Siemionow M. New surgical approach in facial transplantation extends survival of allograft recipients. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:297–303. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000168693.25306.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir Y, Ozmen S, Klimczak A, et al. Tolerance induction in composite facial allograft transplantation in the rat model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1790–1801. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000142414.92308.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir Y, Ozmen S, Klimczak A, et al. Strategies to develop chimerism in vascularized skin allografts across MHC barrier. Microsurgery. 2005;25:415–422. doi: 10.1002/micr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eduardo Bermudez Dez L, Santamaria A, Romero T, et al. Experimental model of facial transplant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1374–1375. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200210000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazici I, Unal S, Siemionow M. Composite hemiface/calvaria transplantation model in rats. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1321–1327. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000239452.31605.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazici I, Carnevale K, Klimczak A, Siemionow M. A new rat model of maxilla allotransplantation. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:338–344. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000237683.72676.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulahci Y, Klimczak A, Siemionow M. Long term survival of composite hemiface/mandible/tongue tissue allograft permitted by donor specific chimerism. San Francisco, CA: Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons; October 6–11, 2006.

- Siemionow M, Agaoglu G, Unal S. A cadaver study in preparation for facial allograft transplantation in humans: part II. Mock facial transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:876–885. discussion 886–888. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000204876.27481.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Agaoglu G. The issue of “facial appearance and identity transfer” after mock transplantation: a cadaver study in preparation for facial allograft transplantation in humans. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22:329–334. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-946709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemionow M, Papay F, Kulahci Y, et al. Coronal-posterior approach for face/scalp flap harvesting in preparation for face transplantation. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22:399–405. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A. Facing ourselves. Am J Bioeth. 2004;4:18–20. doi: 10.1080/15265160490496930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agich G J, Siemionow M. Facing the ethical questions in facial transplantation. Am J Bioeth. 2004;4:25–27. doi: 10.1080/15265160490496921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Working Group-Comité Consultatif National d'Ethique (CCNE): Composite tissue allotransplantation of the face (full or partial facial transplant) February 6, 2004. Available at http://www.ccne_ethique.fr/english/avis/a_082.htm Available at http://www.ccne_ethique.fr/english/avis/a_082.htm

- Ziegelmann J P, Griva K, Hankins M, et al. The transplant effects questionnaire; the development of a questionnaire for assessing the multidimensional outcome of organ transplantation—example of end stage renal disease (ESRD) Br J Health Psychol. 2000;7:393–408. doi: 10.1348/135910702320645381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]