ABSTRACT

Lip reconstruction poses a particular challenge to the plastic surgeon in that the lips are the dynamic center of the lower third of the face. Their role in aesthetic balance, facial expression, speech, and deglutination is not replicated by any other tissue substitute. The goals of lip reconstruction are both functional and aesthetic, and the surgical techniques employed are often overlapping. This discussion will focus on lip defects with significant tissue loss that require flap reconstruction. Flaps described include Webster-Bernard cheek advancement flaps, Abbe cross-lip flaps, Karapandzic rotation advancement flaps, and single and dual free-flap lip reconstructions. The principles and techniques described are broadly applicable to other flap designs that are required to meet both the aesthetic and functional goals of lip reconstruction.

Keywords: Lip reconstruction, Webster-Bernard flap, Abbe flap, Karapandzic flap, free flap

Lip reconstruction poses a particular challenge to the plastic surgeon in that the lips are the dynamic center of the lower third of the face. Their role in aesthetic balance, facial expression, speech, and deglutination is not replicated by any other tissue substitute. The goals of lip reconstruction are both functional and aesthetic, and the surgical techniques employed are often overlapping. The aesthetic goals of lip reconstruction are to provide adequate replacement of external skin while maintaining the aesthetic balance of the vermiliocutaneous junction and lip aesthetic units. The functional goals of lip reconstruction are to maintain intraoral mucosal lining and to preserve the surface area of the oral aperture. The competence of the orbicularis muscle sphincter must also be maintained, as this is critical to achieving a functional recovery.1,2 Ideally, cutaneous sensation is preserved or reestablished to provide proprioceptive feedback for speech, animation, and management of secretions.

There have been countless flaps described to reconstruct the lips with numerous eponyms and modifications associated with them. This can be quite confusing and often a source of miscommunication. Surgical techniques to reconstruct the lips can be differentiated by three main criteria: Is the reconstruction dynamic or static? Is the orbicularis oris muscle sphincter reestablished or is tissue interposed within it? Is the donor tissue from the remaining lip, local cheek tissue, or distant tissue? These aspects of flap design must be considered as they impact the ultimate aesthetic and functional outcome. As an example, a dynamic reconstruction with remaining lip tissue that re-creates the orbicularis sphincter will likely be superior in terms of lip appearance and orbicularis function to a static reconstruction that uses remote tissue interposed between the remaining orbicularis muscle.

This discussion will focus on representative flaps from each category above. Webster-Bernard cheek advancement flaps, Abbe cross-lip flaps, Karapandzic rotation advancement flaps, and free-flap reconstructions will be presented. The principles described are broadly applicable to other flap designs and modifications of the above flaps that are used in lip reconstruction.

ANATOMY

Lip reconstruction requires familiarity with the surface anatomy, underlying muscular anatomy, and neurovascular anatomy of the lower face. The upper lip is composed of the philtrum and tubercle centrally, the paired philtral columns laterally, and the white roll of the vermiliocutaneous junction. The orbicularis oris muscle maintains oral competence by acting as a circumoral sphincter. Its horizontal fibers link the modiolus and philtral columns producing a tightening of the upper lip. Oblique fibers between the commissure and nasal floor act to evert the upper lip. The orbicularis is acted upon by the surrounding elevating and depressing mimetic musculature. The levator labii superioris, levator anguli oris, and the zygomaticus major and minor elevate the upper lip, and the mentalis, depressor labii inferioris, and the depressor anguli oris draw the lip inferiorly.

The blood supply to the lips is derived from the facial artery with the inferior labial artery supplying the lower lip and the superior labial artery and branches from the angular artery supplying the upper lip. Motor innervation arises from the buccal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve; sensory innervation of the upper lip is from the infraorbital nerve V2 and the mental nerve V3 supplies the lower lip.

The lip vermilion separates the skin of the external lip and the mucosa of the inner lip. It is composed of keratinizing glabrous epithelium with numerous sebaceous glands. The transitional area between the keratinizing epithelium of the vermilion and the nonkeratinizing epithelium of the labial mucosa is densely innervated with mucocutaneous end organs.

DEFECTS

The etiologies of lip defects are quite diverse including, oncologic resection, traumatic avulsion, burns and congenital deformities. Defects of the lower lips are more often encountered due to the higher incidence of lower lip cancers. Defects of up to 30% of the transverse width of the lip in adults can typically be closed primarily without significant decrease in oral opening. Defects of the vermilion may require sacrifice of adjacent skin of the prolabium or mentum to allow a vertical realignment of all lip elements without redundancy. This may be designed as a V or an inverted V for narrow defects. Wider defects may require the skin excess to be resected in a curvilinear alar groove or labiomental pattern allowing the remaining lateral lip or lip-cheek junction to advance medially.

Full-thickness defects require meticulous attention to obtain a three-layer closure of mucosa, muscle, and skin. The mucosa must be aligned and everted to provide a watertight mucosal seal. The deep and superficial fibers of the orbicularis muscle must be reapproximated to allow tension-free muscle coaptation and avoid attenuation or muscle dehiscence. Incisions that cross the white roll should be oriented perpendicularly to allow precise realignment of the while roll to avoid a noticeable vermiliocutaneous mismatch or notch. Subtle misalignment of the lip can be aesthetically distracting, even in the absence of significant soft tissue loss. This remainder of this discussion will focus on lip defects with significant tissue loss that require flap reconstruction.

CHEEK ADVANCEMENT FLAPS: WEBSTER-BERNARD FLAP

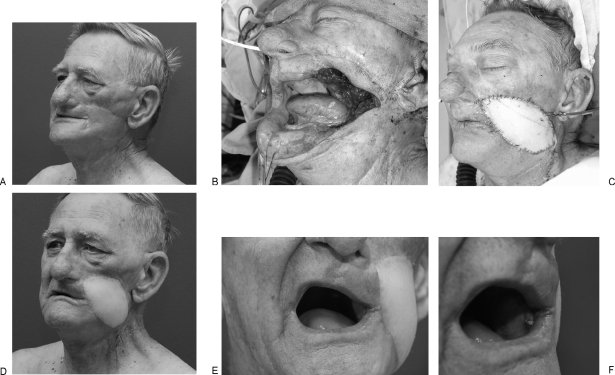

The Webster-Bernard flap is used to reconstruct the lower lip by advancing cheek tissue and the remaining lip tissue medially.3 This technique is well suited for subtotal defects of the lower lip where the commissure is preserved (Fig. 1). Cheek skin is recruited to add length to the lip repair to lessen the degree of microstomia. Simultaneous vermilion reconstruction can be accomplished with this technique through mucosal eversion.4

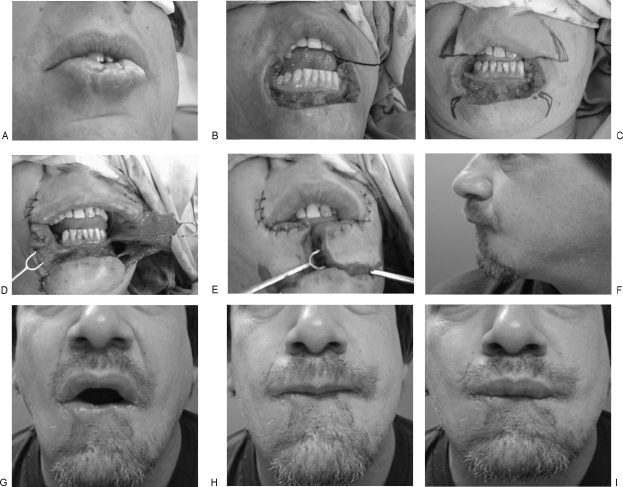

Figure 1.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip reconstructed with the Webster-Bernard flap. (A) Preoperative view. (B) Total lower lip defect; note the commissures are preserved. (C) Planned markings for bilateral cheek advancement with the Webster-Bernard flap. (D) Flaps mobilized; note the extent of mucosa recruited for creation of the vermilion. (E) Flap inset. (F–I) Twelve-month follow-up.

In planning the flap design, the length of each cheek limb equals half of the horizontal lip defect. Triangular curvilinear upper and lower incisions are planned along the nasolabial and labiomental creases. Burow's triangles are excised from the upper incisions. The lower incision can often be advanced without the need for resection of the Burow's triangles due to the laxity of the skin of the chin-cheek junction. The incisions are performed through the subcutaneous tissue and muscle to the level of the mucosa. The mucosa is incised medially but need not be incised laterally as this will stretch with tissue advancement. This allows preservation of intraoral lining. Medially, the mucosa is incised superior to the skin flap design to allow mucosa to be delivered anteriorly and everted to create the vermilion of the reconstructed lip. The medial edges of each flap are inset with a three-layer closure. Realignment of the native lip vermilion is accomplished by an overlapping vermilion advancement to prevent central notching at the junction of the two flaps.

The Webster-Bernard flap provides reliable resurfacing of large lip defects with adjacent cheek skin. Adding local tissue to the lip reduces the incidence of microstomia. Its potential disadvantages include notching of the central lip incision and effacement of the gingivobuccal sulcus.5 It also is an adynamic reconstruction, and when used in the lower lip, it requires care in setting tension of lower lip to maintain oral competence. Care should be taken when planning this flap in patients who have had previous facial surgery and previous neck dissections as previous incisions and facial artery ligation can alter the reliability of the cutaneous circulation.

ROTATION ADVANCEMENT LIP FLAP: KARAPANDZIC FLAP

The Karapandzic flap was designed to reestablish the circumoral sphincter by rotating and advancing the remaining innervated orbicularis oris muscle.6 In theory, the lip is rebuilt with innervated-like tissue. However, the net circumference of the lip is reduced. The Karapandzic flap can be used to resurface up to near-total defects of both the upper and lower lips, though superiorly based flaps for lower lip defects are more common. The key to flap design is to assess the vertical height of the defect and translate that dimension to the width of the flap. This allows a curvilinear incision to be plotted upwards toward the alar base. These incisions can fall within the nasolabial fold or parallel to it with acceptable donor-site scarring.

Dissection is performed to release muscle fibers and suspensory ligaments while taking great care to preserve the inferior and superior labial artery branches and the buccal motor nerve branches to the orbicularis as they enter the muscle at its lateral extent (Fig. 2). Bipolar cautery and a nerve stimulator facilitate the intramuscular dissection. Minimal incision of the underlying mucosa is performed, as the mucosal laxity will allow advancement for closure. The overall lip circumference is reduced to close the defect with a corresponding decrease in stoma surface area. Critical microstomia is the limit of the flap design. Lesser degrees of microstomia can be addressed secondarily with cross-lip flaps to transfer relative lip excess to areas of deficiency.

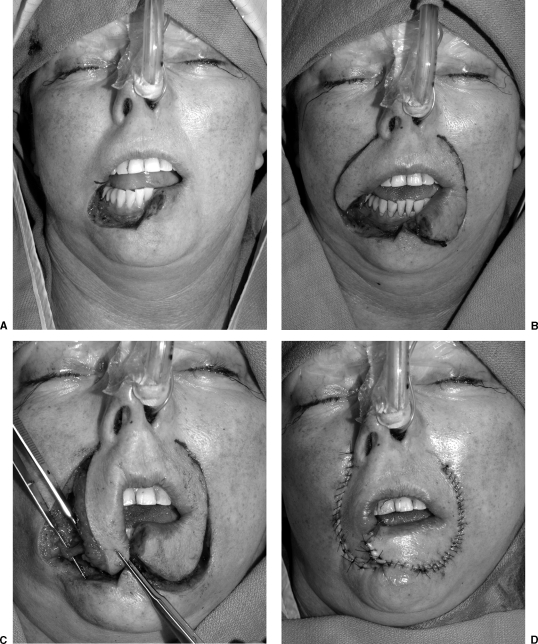

Figure 2.

T2 N0 squamous cell carcinoma subtotal lower lip defect reconstructed with a Karapandzic flap. (A) Extirpative defect. Right commissure marked. (B) Flap design along nasolabial fold. (C) Flaps mobilized. Neurovascular pedicle isolated and preserved. (D) Flap inset. (All photos copyright © 2007, Matthew Hanasono, M.D.)

The Karapandzic flap can provide a dynamic functional reconstruction with smaller innervated flaps preserving better function. Although the flaps remain innervated, the tension created by flap advancement in the face of larger tissue loss reduces the lower lip to a tightened band.7 Subtle dynamic motion is replaced by tethered scar. As with cheek advancement flaps, effacement of the anterior gingivobuccal sulcus may require revising and deepening with a skin graft to improve salivary competence.

CROSS-LIP FLAP: ABBE FLAP

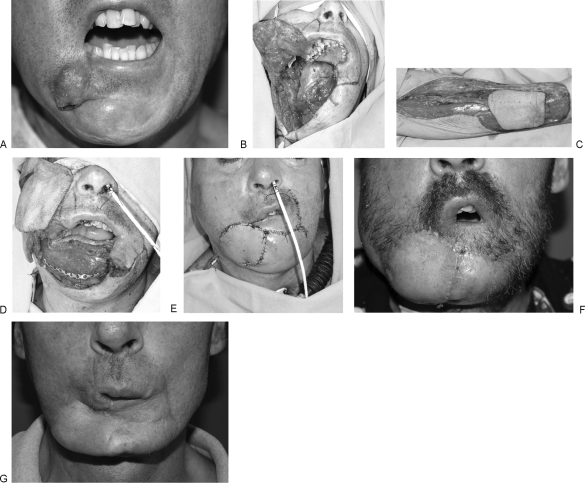

The cross-lip flap, or Abbe flap, is a staged flap based on the labial artery. The Abbe flap is well suited for both upper and lower lip reconstructions. It is more commonly used as a lower lip flap transferred to the upper lip with both the central and lateral lower lip serving as a donor site. However, when the upper lip is used as donor tissue, the central philtral region is preserved given the delicate aesthetic balance of the central upper lip. The lateral upper lip serves as a donor site more commonly for transfer to the lower lip. Defects that are well suited to Abbe flaps are central full-thickness defects that do not involve the commissure.8 One advantage of the cross-lip flap is the ability to replace a vertical segment of both vermilion and cutaneous lip tissue. An inferiorly based Abbe flap can be extended to also include skin from the chin to resurface a defect extending into the nasal floor (Fig. 3).

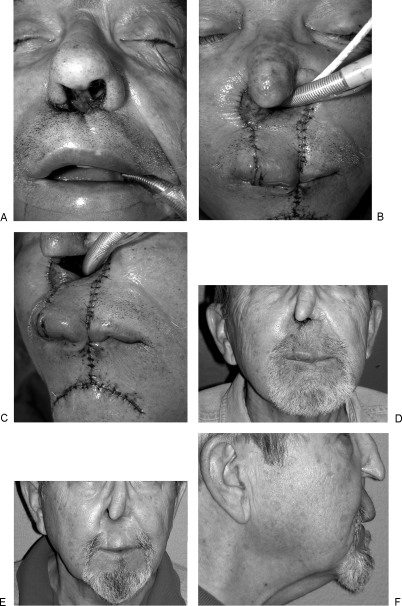

Figure 3.

Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of nasal vestibule and upper lip treated previously with radiation. (A) View of planned resection of nasal vestibule, septum, and upper lip. (B) Abbe flap with addition of mental skin to resurface defect of nasal floor. (C) Width of flap design was based on wider tissue requirement of nasal floor than of upper lip defect. (D) Result at 2 weeks before flap division. (E) Three-month follow up. (F) Lateral view; projection of the central lip preserved. (All photos copyright © 2007, Roman Skoracki, M.D.)

The defect is assessed and the flap is designed to be half as wide as the defect to allow for balanced upper and lower lip lengths after flap transposition. The flap survives on an axial blood supply and can be reliably narrowed allowing the flap to pivot and rotate into the defect. In selecting which side of the lip to set the base of the flap, the pivot point is placed closest to the commissure to allow a more proximal blood supply and a more lateral pivot point. This allows a maximal distance from the opposite commissure to the flap pedicle and maintains the oral opening as wide as possible. Flap division is performed at 3 weeks. A compliant patient is paramount to the success of this flap as diet, speech, and socialization are altered during the staged reconstruction.

Abbe flaps are also useful options for revising lip reconstructions as secondary lip-balancing procedures. If there is a relative deficiency in lip length after a circumoral lip reconstruction, an Abbe flap can be interposed to the shortened lip segment restoring balance. The main disadvantages are the intervening period of lip adhesion and the potential imbalance of the vermilion and white roll on either side of the two suture lines.

FREE-FLAP RECONSTRUCTION OF LARGE LIP DEFECTS

Free-flap reconstruction is often required for large-scale defects with associated loss of mucosa, cheek, nasal, and chin skin that exceed the availability of local soft tissue. This can be due to paucity of available soft tissue, previous radiation therapy, or previous surgery (Fig. 4). While free-tissue transfer can provide an abundance of soft tissue, care must be taken in selecting a donor site with an appropriate match in color, texture, and pliability.

Figure 4.

T4 N0 squamous cell carcinoma of nasal cavity, columella, and upper lip. (A) Extirpative defect after total rhinectomy, palatectomy, bilateral maxillectomies, and resection of upper lip resulting in large confluent oro-nasal cavity. (B) Palate and upper lip reconstructed with folded radial forearm flap. The flap was oriented such that the radial and ulnar borders were inset posteriorly allowing the pedicle to travel laterally to the left facial vessels. A palmaris sling anchored to the zygomatic bone supported the flap. (All photos copyright © 2007, Donald Baumann, M.D.)

The radial forearm flap has been used extensively because of its thin profile, long pedicle, and reasonable color match9,10 (Fig. 5). Parascapular flaps have also been used preferentially in facial reconstruction because of their excellent color match with facial skin.11 With the advent of perforator flaps, the thoracodorsal artery perforator flap, internal mammary artery perforator flap, anterolateral thigh flaps, and lateral arm flaps have become options for facial reconstruction available to the reconstructive microsurgeon.12 Perforator flaps allow tissue to be thinned based on a preferential cutaneous blood supply and in theory are fascial and muscle sparing thus reducing donor-site morbidity. These flaps typically provide reasonable color match and, depending on body habitus, have the ability to be folded and contoured re-creating the internal and external lining of the lip. When additional flap volume is required, the anterolateral thigh flap (ALT) with or without the vastus lateralis muscle is well suited to reconstruct defects of the central and lower face. The ALT flap is ideal for large through-and-through cheek defects with lip involvement when two skin islands are required13,14 (Fig. 6). An advantage of internal mammary artery perforator, lateral arm, and parascapular flaps is color match with facial tissues; however, pedicle length must also be taken into account when selecting these donor sites for lip reconstruction.

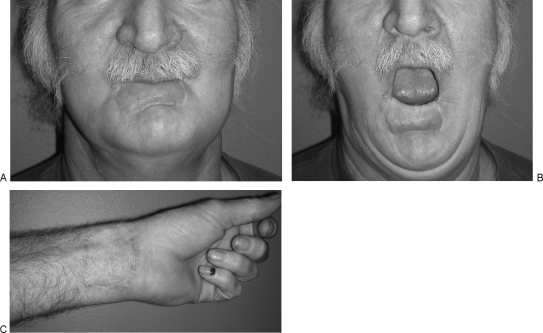

Figure 5.

Eight-month follow-up after radial forearm free-flap reconstruction of lower lip defect. (A) Lip in repose. Flap was supported with fascia lata sling anchored to the modiolus. Of note, the palmaris tendon was absent. (B) Lip circumference symmetrically preserved. (C) Healed donor site. (All photos copyright © 2007, Roman Skoracki, M.D.)

Figure 6.

Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma after previous reconstruction with vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap and radiation therapy. (A) Preoperative appearance. Note the tethered scar retraction and lateral displacement of the commissure. Intraoral soft tissues are also contracted and fixed. (B) Full-thickness cheek defect including the lateral element of the upper and lower lips and commissure. (C) Reconstruction with dual paddled anterolateral thigh flap and fascia lata sling anchored to the zygomatic bone. The upper and lower lip elements were advanced to create a new commissure supported by the underlying ALT flap. (D) Follow-up at 8 weeks. (E) Improved mouth opening. (F) Reconstructed commissure maintains anatomic position upon mouth opening. (All photos copyright © 2007, Donald Baumann, M.D.)

Accurate assessment of three-dimensional tissue loss and required volume for reconstruction is paramount to the success of a lip reconstruction. Lip defects often appear more dramatic than they are in actuality because of the displacement of wound edges due to the lateral pull of the facial muscles. The first step in deciding on flap dimension is to reestablish the resting tension of the edges of the lip defect. The other lip can be used as a guide to reestablish the aesthetic dimension of the lip. Next, an Esmarch template is fashioned and sewn to the remaining lip elements and folded to account for the three-dimensional tissue requirements of the defect. Precision is required in determining the length of the external skin deficit given the delicate balance of lip aesthetic units. The mucosal requirement can be slightly overestimated to allow excess tissue to deepen the gingivobuccal sulcus and limit intraoral scar contracture.

Next, recipient vessels must be selected. The facial vessels are of adequate caliber and readily accessible at the angle of the mandible. An anastomosis at this level requires a pedicle length of ~8 cm, which is readily available with any flap design. If the facial vessels are too small or unavailable due to previous surgery, then recipient vessels must be sought elsewhere in the external carotid system. One advantage in selecting recipient vessels for a lip reconstruction is that either side of the neck can be used allowing the surgeon to avoid a previously operated neck or primarily radiated neck. Recipient vessels are reached through a subcutaneous tunnel. The tunnel must be designed to allow the pedicle to travel in a direct path avoiding kinks, twists, or compression.

The inset of a thinned perforator flap is performed by folding the flap on itself to create internal mucosal lining and external cutaneous coverage. Alternatively, if the flap cannot be folded, the cutaneous portion can be used for intraoral lining, and the external portion of the flap can be covered with a skin graft. The flap design should plan for pedicle orientation in the coronal plane to avoid the pedicle being folded on itself and compressed in the sagittal plane. The flap inset is guided by aligning external lip structures and interposing flap skin island under slight tension. This is done to establish the resting tone of the lip to prevent ptosis and salivary incompetence. Attention to deepening the anterior gingivobuccal sulcus will improve the patient's ability to manage secretions, tolerate liquids, and avoid drooling.

If the central mimetic musculature or distal facial nerve branches have been resected, the reconstructed lip must be supported with either a static or dynamic sling. Static sling free-flap reconstruction requires suspension of the lateral element of the lip with rolled fascia grafts or prosthetic or bioprosthetic materials. The vector can be set using either the modiolus or zygomatic body as a point of fixation depending on the presence or absence of the facial nerve function. Bony anchors offer stable fixation and enable fine-tuning of the vector of lip elevation.

The previously discussed aesthetic benefits of radial forearm flaps and perforator flaps including thin tissue mass, pliability, and color match are offset by the lack of functional dynamic motion. These flap donor sites all lack motor innervation and voluntary tightening of the lip. All lower lip static reconstructions are essentially tension bands that relax with time and lose aspects of their barrier function. Dynamic slings can also be incorporated into free-flap lip reconstructions to improve the degree of voluntary control of commissure position and lip tone. Techniques that use both free flaps for lip resurfacing and temporalis muscle turn-down flaps for lip elevation have been described for this purpose.15 This technique may prevent ptosis of the lateral lip, but with time the degree of function achieved does not compare with the native lip's mobility.

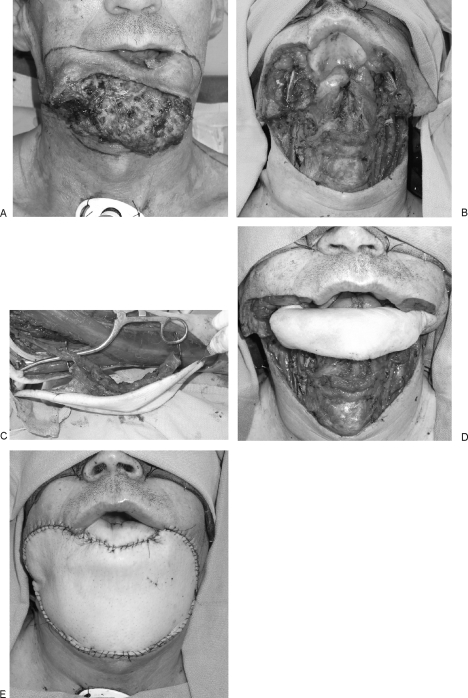

Often, total lip defects are accompanied by large-scale resections of surrounding tissue including the nasal floor, nose, mandible, floor of mouth, chin, cheek, and neck. These complex volumetric and topographic defects often require tissue replacement in excess of that available with any one flap. Dual free-flap reconstructions can be employed to reconstruct these extensive intraoral and extraoral defects.16 These flaps may be used to provide a platform to support the lip reconstruction by a local flap or they might provide the lip reconstruction itself17 (Figs. 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

T4 N0 squamous cell carcinoma of the mandible eroding through to external skin and undermining the lower lip. (A) Preoperative appearance. (B) Defect after hemimandibulectomy and resection of lower lip and chin-cheek skin. The defect required intraoral bone and soft tissue reconstruction that was provided by a fibula osteocutaneous flap. A radial forearm flap provided external skin coverage. (C) Radial forearm skin island. (D) Fibula inset and radial forearm flap revascularized. Lip reconstruction was planned with a unilateral Karapandzic flap. (E) Intraoperative result after flap inset. (F) Result at 4 weeks. Reconstructed right lower lip is well supported by the soft tissue framework below; however, the shortened lip length has led to reduction in oral opening. (G) Result at 8 months after completion of radiation therapy. Note the improved contour of radial forearm flap. (All photos copyright © 2007, Matthew Hanasono, M.D.)

Figure 8.

Exophytic squamous cell carcinoma of mandible and lower third of the face. (A) Preoperative appearance. (B) Extirpative defect including angle-to-angle mandibulectomy, resection of floor of mouth, lower lip, chin and neck skin. This defect required a dual free-flap reconstruction, bone and soft tissue intraoral reconstruction, and a large soft tissue flap for external neck and chin coverage. Given the extent of lip and intraoral resection, there were limited options for the lip reconstruction. The fibula skin island was used for resurfacing of the lower lip in addition to intraoral coverage. (C) Harvest of fibula with large skin paddle. (D) Fibula inset with soft tissue platform for lip reconstruction. (E) Intraoperative result with ALT flap resurfacing the chin and cheek and neck skin. (All photos copyright © 2007, Matthew Hanasono, M.D.)

The next step in refining free-tissue lip reconstruction is to develop flaps that can meet both the aesthetic and functional demands of the lip. The aesthetics have been refined through our current flap selection. However, the need for voluntary controlled intrinsically dynamic flap designs has not been met.18 These characteristics are not readily available in any given flap donor site. However, as dual free-flap reconstruction for complex head and neck reconstruction has become more commonplace, extensive total lower lip defects may be amenable to a dual-flap trilaminar dynamic reconstruction. As an example, innervated a gracilis muscle flap placed between the folded skin islands of a radial forearm flap has been reported for dynamic lower lip reconstruction.19 The authors report reasonable orbicularis functional outcome with ability to voluntarily animate the flap. Another area of investigation into flap designs that meet the highly specific tissue needs of the lips is prelamination of select donor sites. Prelamination can combine reliable functional muscle transfers with thin pliable cutaneous coverage for single-flap complex lip reconstructions.20

REVISIONS

Most lip reconstructions require revision after a period of interim healing and completion of adjuvant therapy. The advanced tumor stage of larger lip defects often requires radiation therapy for oncologic control. Radiation therapy inevitably alters the aesthetic outcome resulting in hyperpigmentation, fibrosis, edema, and pin-cushioning. When evaluating a patient for a lip revision, it is important to consider the appearance and function of the lip as well as the patient's goals. The lip must be viewed in relation to its subunits: external skin of the mentum and prolabium, vermilion, commissure, and mucosa. Options for vermilion revisions include facial artery musculomucosal flaps,21 mucosal advancement flaps, commissureplasties, and tongue flaps. Intraoral scar release and skin grafting to deepen the gingivobuccal sulcus can provide dramatic improvement in the ability to manage secretions and liquids. Full-thickness skin grafts can be used to resurface the aesthetic units of the lip and chin. In men, asymmetries in the reconstructed upper lip can be camouflaged by resurfacing the lip with a hair-bearing temporoparietal fascial flap.22 These revisional efforts can have a significant impact on the patient's sense of body image and their ability to resume their personal and professional lives.

CONCLUSION

In planning a lip reconstruction, all aspects of flap design must be considered as they impact the ultimate aesthetic and functional outcome. A dynamic reconstruction with remaining lip tissue can provide superior results in terms of lip appearance and function in smaller lip defects. Reconstruction of large-scale defects often requires free-tissue transfer that provides static support of the lip. Further refinements in free-flap design are needed to provide dynamic reconstructions that re-create the function of the lip and preserve oral competence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge their colleagues Matthew Hanasono, M.D., and Roman Skoracki, M.D., who contributed their cases to this work.

REFERENCES

References

- Adams W, Beran S. Lip, cheek, and scalp reconstruction; hair replacement. Selected Readings in Plastic Surgery. 2001;15:2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll S. In: Kroll S, editor. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery for Cancer. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1996. Lip reconstruction. pp. 201–209.

- Webster R C, Coffey R J, Kelleher R E. Total and partial reconstruction of the lower lip with innervated muscle-bearing flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1960;25:360–371. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196004000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closmann J J, Pogrel M A, Schmidt B L. Reconstruction of perioral defects following resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langstein H N, Robb G L. Lip and perioral reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:431–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karapandzic M. Reconstruction of lip defects by local arterial flaps. Br J Plast Surg. 1974;27:93–97. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(74)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civelek B, Celebioglu S, Unlu E, Civelek S, Inal I, Velidedeoglu H V. Denervated or innervated flaps for the lower lip reconstruction? Are they really different to get a good result? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgarelli A C, Sartorelli F, Cangiano A, Collini M. Treatment of lower lip cancer: an experience of 48 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng S F, Kuo Y R, Wei F C, Su C Y, Chien C Y. Total lower lip reconstruction with a composite radial forearm-palmaris longus tendon flap: a clinical series. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:19–23. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000090722.16689.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadove R C, Luce E A, McGrath P C. Reconstruction of the lower lip and chin with the composite radial forearm-palmaris longus free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:209–214. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granick M S, Newton E D, Hanna D C. Scapular free flap for repair of massive lower facial composite defects. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8:436–441. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890080607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giessler G A, Cornelius C P, Suominen S, et al. Primary and secondary procedures in functional and aesthetic reconstruction of noma-associated complex central facial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:134–143. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000263657.49956.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim S, Gideroglu K, Aydogdu E, Avci G, Akan M, Akoz T. Composite anterolateral thigh-fascia lata flap: a good alternative to radial forearm-palmaris longus flap for total lower lip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2033–2041. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000210663.59939.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng S F, Kuo Y R, Wei F C, Su C Y, Chien C Y. Reconstruction of concomitant lip and cheek through-and-through defects with combined free flap and an advancement flap from the remaining lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:491–498. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000100809.43453.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M, Yotsuyanagi T, Yokoi K, Urushidate S, Yamashita K, Higuma Y. One-stage reconstruction of a large defect of the lower lip and oral commissure. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng S F, Kuo Y R, Wei F C, Su C Y, Chien C Y. Reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects with large lip involvement by using double free flaps and fascia lata grafts for oral sphincters. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1830–1836. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000164688.44223.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro P G, Santamaria E. Primary reconstruction of complex midfacial defects with combined lip-switch procedures and free flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1850–1856. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovic M, di Spilimbergo S S, Ninkovic M. Lower lip reconstruction: introduction of a new procedure using a functioning gracilis muscle free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1472–1480. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000258527.99140.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Oba S, Ohtani K, Amano N, Fumiyama Y. Functional lower lip reconstruction with a forearm flap combined with a free gracilis muscle transfer. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:867–870. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribaz J J, Fine N, Orgill D P. Flap prefabrication in the head and neck: a 10-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:808–820. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribaz J J, Meara J G, Wright S, Smith J D, Stephens W, Breuing K H. Lip and vermilion reconstruction with the facial artery musculomucosal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:864–872. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J C, Hadlock T, Varvares M A, Cheney M L. Hair-bearing temporoparietal fascial flap reconstruction of upper lip and scalp defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:170–177. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Editor's Comments

Drs. Baumann and Robb have written an outstanding review of their reconstructive management of large lip defects.

They reflect the current consideration that the upper limits of a lip defect to be closed primarily is limited to 30%.

However, we have found that in selected patients defects up to 45% can be closed with a “V” wedge incision closure. The resulting lip is functional, but admittedly unbalanced. Overall, we still feel this provides the best functional resection option.

Also, for upper lip skin only defects, peri-alar crescentric advancement flap can provide color matched coverage of up to 35% defects in selected patients.

James F. Thornton, M.D.

Figure 1.

Interoperative/postoperative views of a nearly 50% lower lip defect closed by wedge excision/closure.

Figure 2.

30% skin only upper lip defect reconstructed with a peri-alar crescentric advancement flap.