ABSTRACT

Reconstruction of composite maxillofacial defects after tumor excision or trauma is difficult. The role of the reconstructive surgeon is to have a diverse armamentarium of reconstructive options to enable an aesthetic and functional reconstruction while minimizing the morbidity to the patient. This article will present a systematic review of composite maxillofacial reconstruction with free tissue transfer.

Keywords: Reconstruction, maxilla, mandible, osteocutaneous free flaps

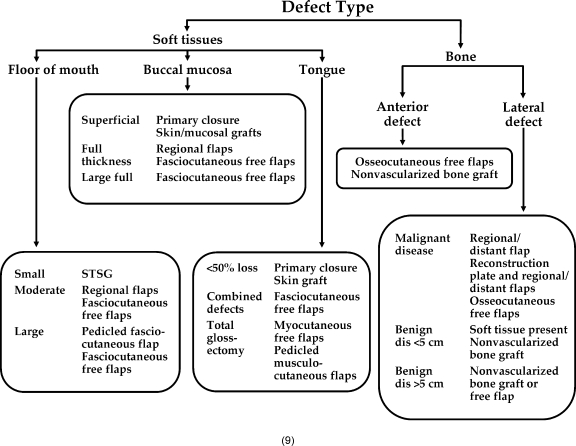

Reconstruction of maxillofacial defects poses a considerable challenge for reconstructive surgeons. Defects typically arise from oncologic ablative surgery, trauma, or congenital anomalies and can have a significant functional impact on a patient's quality of life. The patient's ability to speak and take adequate oral alimentation is often severely compromised along with deleterious effects on facial aesthetics. Advances in reconstructive surgical techniques have led to a decrease in functional and aesthetic sequelae; therefore, it is critically important for the reconstructive surgeon to have a diverse armamentarium of reconstructive options (Table 1). A variety of flaps can then be tailored to the individual patient's reconstructive needs, tolerance for donor-site morbidity, and general physical and psychological state.

Table 1.

Options for Facial Reconstruction

| • No reconstruction |

| • Primary closure |

| • Secondary intention |

| • Local |

| • Regional |

| • Free flap |

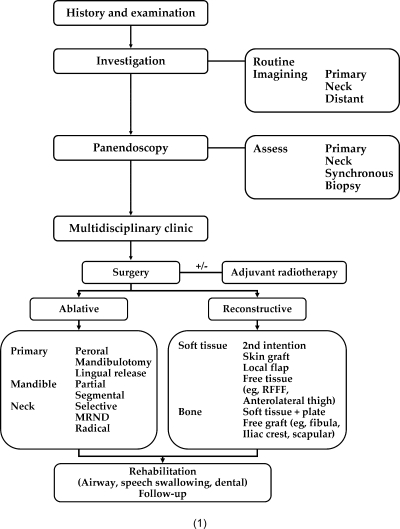

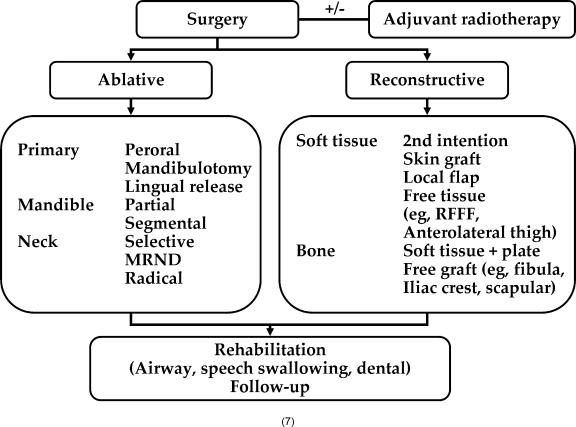

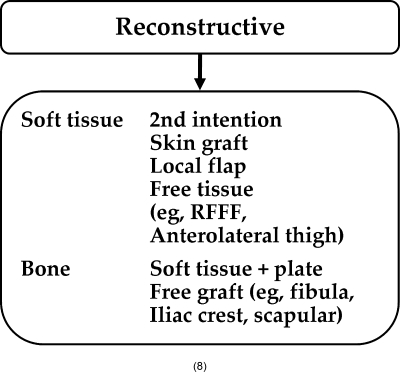

In this article, we will aim to provide a general overview of the various options currently available in contemporary head and neck surgery for composite bone reconstruction (see Figs. 1 to 9). The field of reconstructive facial surgery has significantly evolved over the past 30 years with the advent and now-common use of free tissue transfer, which has revolutionized our abilities for tumor extirpation and immediate functional reconstruction of extensive head and neck defects. As we consider the goals of every reconstruction, we have to be mindful of the patient's overall disease state, long-term prognosis, medical comorbidities, and desire for functional reconstruction (Table 2). Several critical features such as need for postoperative adjuvant therapy or reestablishment of dentition for mastication with endosteal dental implants along with the presence of medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease or peripheral vascular disease have to be taken into account to define an ideal reconstructive procedure for any given patient.

Table 2.

Important Aspects of Preoperative Evaluation

| Patient Factors |

| • Smoking |

| • Alcohol |

| • Medical comorbidities |

| • Prior irradiation |

| Defect |

| • Size |

| • Location |

| • Dentition |

| • Options for prosthetic reconstruction |

| • Dental rehabilitation |

| • Donor-site morbidity |

Composite facial reconstruction has evolved to use free vascularized bone flaps routinely. The free fibula, iliac crest, and scapula vascularized bone flaps have developed to be the most commonly used vascularized bone flaps for both midfacial and mandibular reconstruction.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 The use of these vascularized flaps allows for reconstruction of both large and small composite defects in both irradiated and nonirradiated fields. Although nonvascularized bone grafting continues to be useful, it is mainly beneficial in small (less than 5 cm) structural defects with an appropriate soft tissue envelope in a nonirradiated, well-perfused recipient site.8

We have not included herein discussion of primary or secondary skin grafting or rotational flap techniques. With this in mind, this article is organized based on flap design for composite bone reconstruction of the facial skeleton. These categories are by no means comprehensive and are based on the most commonly used options in contemporary reconstructive practice.

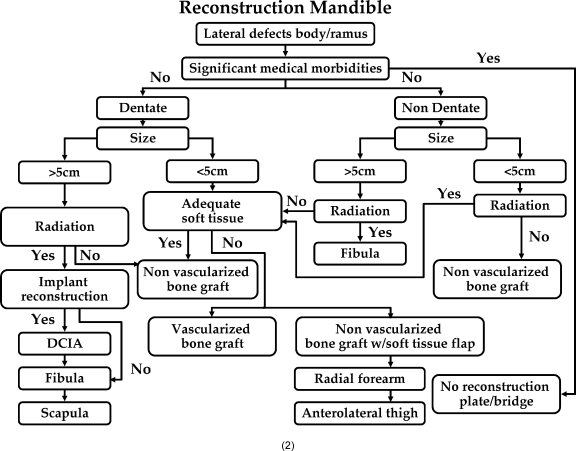

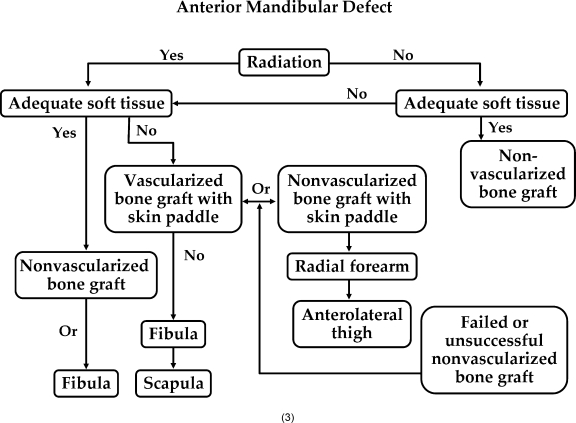

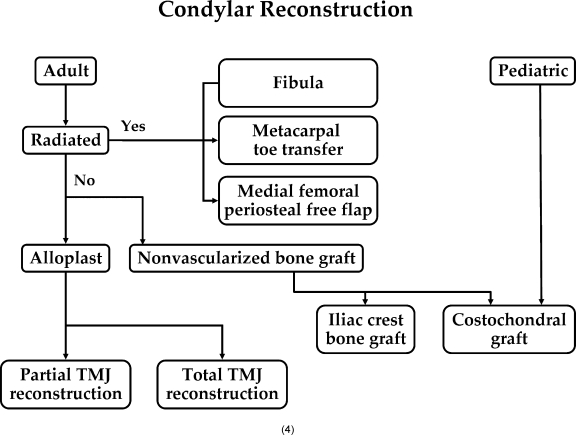

MANDIBULAR RECONSTRUCTION

The mandible, for descriptive purposes, is divided into several anatomic areas: symphysis, parasymphysis, body, region, angle, ramus, and condyle. Each of these areas possesses a unique quality and need for structural and functional integrity that must be considered when planning an appropriate reconstruction. Segmental defects of the mandible can pose a significant challenge to the reconstructive surgeon. They are often associated with significant debilitation and compromise the patient's ability to speak, swallow, and masticate. Although multiple reconstructive options exist, free tissue transfer has increasingly become the dominant reconstructive tool for segmental defects of all regions of the mandible. The success rates for free flap reconstruction are generally high with excellent functional outcomes with appropriate donor-site flap selection. Nonvascularized bone grafts continue to be well suited for small (less than 5 cm) mandibular defects with adequate soft tissue coverage in nonirradiated bone.8 However, when the segmental defects exceed 5 cm in length, the potential for graft failure and dehiscence begins to increase. It is critical for the success of nonvascularized bone grafts to have rigid fixation and a watertight mucosal closure to prevent salivary contamination of the bone graft site. Without these two vital components and an appropriate immunocompetent host without significant risk factors for infection, graft failure is more prone to occur. Therefore, nonvascularized bone grafts are generally restricted to small bone-only defects of the mandible (Fig. 1). Large segmental defects (> 5 cm), especially including overlying mucosa, are best addressed with free tissue transfer. In addition, nonvascularized bone grafts should be used with caution in heavily irradiated fields where tissue perfusion is compromised and mucosal breakdown and graft loss more prone to occur in the patient (Fig. 2). Distraction osteogenesis has primarily been used for univector lengthening of the mandible in cases of congenital hypoplasia and has not been used to date for complex postoncologic reconstruction.

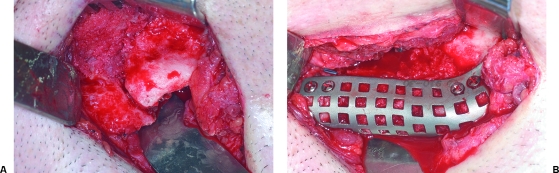

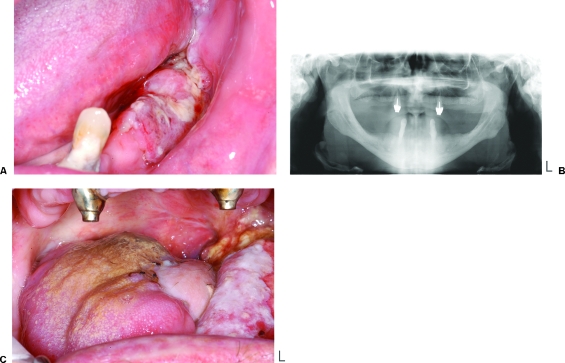

Figure 1.

(A) Left mandible pathologic fracture secondary to elective third molar removal. Multiple transoral attempts at bone grafting failed due to intraoral dehiscence. (B) Definitive reconstruction was performed with nonvascularized iliac crest bone graft with titanium mesh tray.

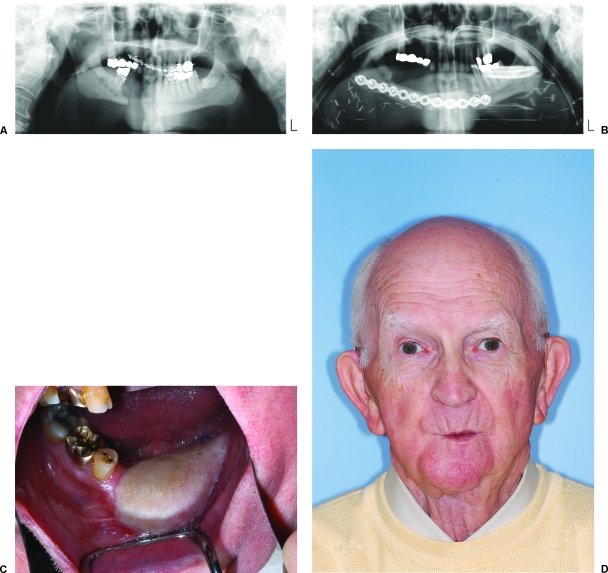

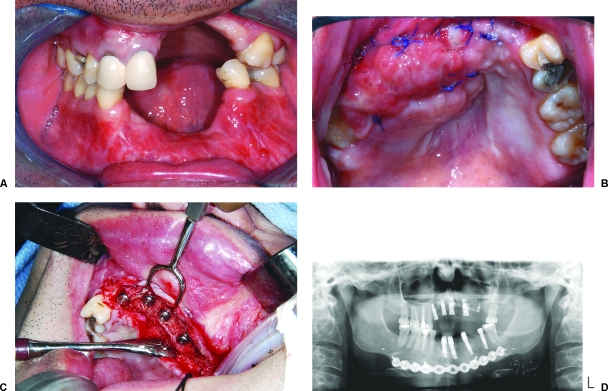

Figure 2.

(A) Osteoradionecrosis of left mandible with pathologic fracture. (B) It is treated with resection and immediate free fibula osteocutaneous flap reconstruction. (C) Postoperative panoramic radiograph after free fibula flap reconstruction. (D) Secondary placement of osseointegrated dental implants into native mandible after indentialation of remaining teeth. Note the excellent contour of the skin paddle used for intraoral lining.

The two main vascularized reconstructive options that have emerged for mandibular reconstruction are the fibula and iliac crest; the choice of flap is centered around whether the patient is dentate or nondentate and whether the ultimate reconstructive goal is the provision of osseointegrated dental implants.3,9 The free fibula provides ~25 to 30 cm of dense cortical bone that may be used for a total mandibular reconstruction if necessary.3,7,10 The donor site is relatively low, and patients are able to resume normal ambulation in the immediate postoperative period. A potential downside of the free fibula flap is associated with the skin paddle, which is limited in size and flexibility (Fig. 3). The iliac crest composite free flap also provides an excellent choice for hemimandibular reconstruction in the dentate patient providing a significantly greater volume of bone mirroring the native hemimandible more closely in all three-dimensional spatial relations (Fig. 4). The disadvantages of the iliac crest include a relatively immobile skin paddle, and it has historically been associated with a greater risk of postoperative donor-site pain, hernia formation, and ambulation difficulty.6,9 In addition, the soft tissue envelope when harvested with the internal oblique can make the iliac crest a somewhat bulky flap even in slender patients.

Figure 3.

(A) Patient sustained a ballistic injury to the face with a comminuted right body and symphysis mandibular fracture treated elsewhere with multiple failed attempts at nonvascularized iliac crest bone grafting. (B) Patient developed an orocutaneous fistula to the mandibular hardware. Patient treated with a single-stage resection and immediate reconstruction with osteocutaneous fibula free flap with extraoral skin paddle for resurfacing the neck.

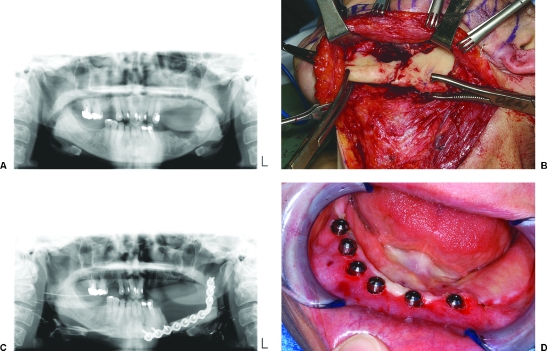

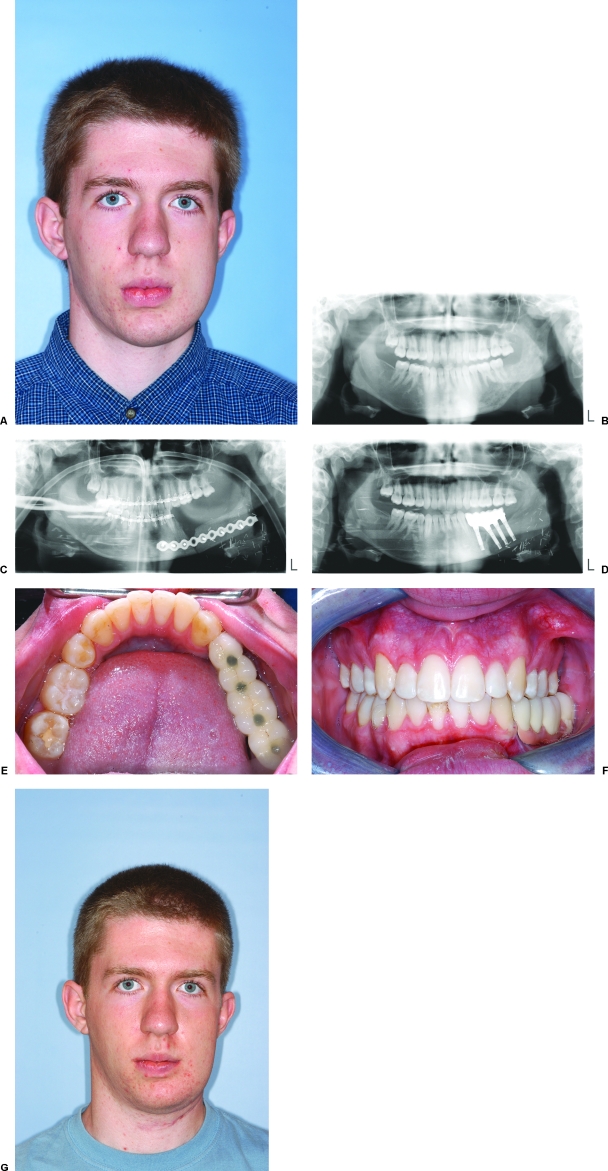

Figure 4.

(A) Patient with refractory acute/chronic osteomyelitis resistant to medical therapy. (B) Preoperative panoramic radiograph. (C) Patient was treated with a single-stage hemimandibular resection and immediate reconstruction with vascularized iliac crest free flap. (D) Secondary-stage procedure was performed for placement of osseointegrated dental implants. (E) Postoperative occlusal view of mandible. Note the bone volume is close to the native mandible. (F) Completed final occlusion. Note the excellent facial symmetry (A) before and (G) after surgery and occlusion achieved with prosthetic reconstruction.

The free fibula flap is well suited for edentulous mandibular reconstruction as the fibula height tends to mirror the height of an edentulous mandible. In many patients, the fibula de novo may not be suitable for placement of osseointegrated dental implant as the bone height is usually significantly less than that provided by an iliac crest free flap. To compensate for this the fibula may be positioned toward the native alveolar bone, rather than toward the inferior border of the remaining mandible. Vertical height may also be augmented with distraction osteogenesis, and refinements in prosthodontic delivery can all compensate and make the fibula an excellent and viable alternative for mandibular reconstruction in dentate patients desiring dental rehabilitation.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21

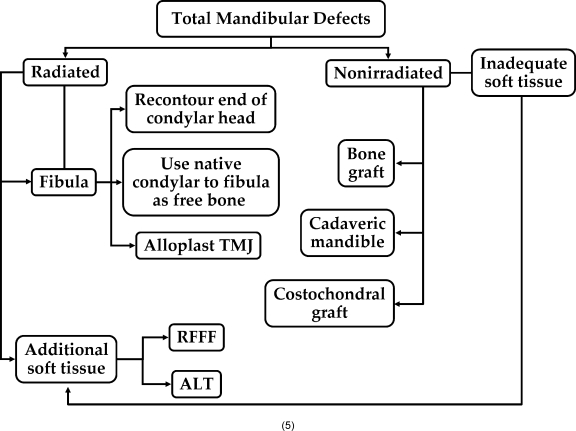

For extensive composite mandibular defects, a dual free flap approach may be necessary with the use of a free fibula osteocutaneous free flap or iliac crest for bony reconstruction followed by a radial forearm free flap or anterolateral thigh free flap for relining of the intraoral cavity (Fig. 5). Although this is a time-consuming and highly complicated approach, it can provide a great deal of flexibility for a tailored reconstruction for a specific patient's defect.22,23,24,25,26,27,28 As previously discussed, the various regions of the mandible will require a different systematic approach when considering bone reconstruction. The anterior mandible is usually the area of greatest stress from mastication and plays an important role in suspension of the airway, tongue, and floor of the mouth. In this region, segmental defects are not well tolerated. Reconstructions aimed at bridging the defect without bone reconstruction can only be performed as a short-term measure as complications from plate dehiscence and fracture are high. Bone reconstruction can be undertaken with nonvascularized bone graft or free tissue transfer such as a fibula free flap. No reconstruction or bridging the defect is acceptable only as a palliative measure in patients with an overall poor prognosis or with significant medical comorbidities where they will not be able to tolerate a more advanced procedure (Fig. 6).29 Lateral mandibular defects are typically associated with lower stress forces and have the option of not being reconstructed if desired by the patient (Fig. 7). Successful reconstruction in this site can occur with a reconstruction plate without formal bony reconstruction. However, should this occur, there will need to be adequate coverage of the hardware with a pedicle or a microvascular soft tissue flap. Plate fractures and orocutaneous exposure tend to occur with some degree of frequency when bony reconstruction is not performed. This type of temporizing or bridging option is most appropriate for an elderly patient with significant comorbidities who is unwilling or unable to tolerate a microvascular operation and should not be recommended for young patients with otherwise good prognosis. Posterior mandibular defect including descending ramus and mandibular condyle can be successfully reconstructed with nonvascularized bone grafting from the iliac crest or costochondral graft. However, in irradiated patients or patients with significant defects, reconstruction with a free fibular osteocutaneous free flap remains an excellent choice. The proximal end of the free fibula flap may be contoured to resemble a native condyle, or in the non–disease-affected mandibular condyle, the condyle may be used as a free bone graft and secured to a native free fibula flap to provide the optimal articulating reconstructive surface.4,30,31,32 In situations where bony reconstruction is not appropriate, large defects can be obliterated by using the rectus abdominus free flap or a pectoralis major myorotational flap to prevent salivary contamination of the neck.33

Figure 5.

(A) Patient with advanced-stage T4 tumor of the retromolar trigone with involvement of the adjacent tongue and floor of the mouth. In oncologic tongue defects greater than one-half the lateral border of the tongue, for optimal tongue motion, a dual free flap approach can be considered. (B) Preoperative panoramic radiograph. (C) This case was reconstructed with a free fibula osseous free flap for mandible reconstruction with a radial forearm free flap for tongue and floor of mouth reconstruction. Patient has excellent speech and was able to take oral alimentation in the immediate postoperative period.

Figure 6.

(A) Elderly patient who presented with a mandibular defect after undergoing several attempts at nonvascularized bone grafting elsewhere. Both anterior and posterior iliac crest sites previously used. (B) Postoperative panoramic radiograph. (C) Patient treated with osteocutaneous free fibula with skin paddle for intraoral resurfacing. (D) Postoperative facial appearance. He did not want to pursue prosthetic reconstruction therefore did not undergo osseointegrated dental implant placement.

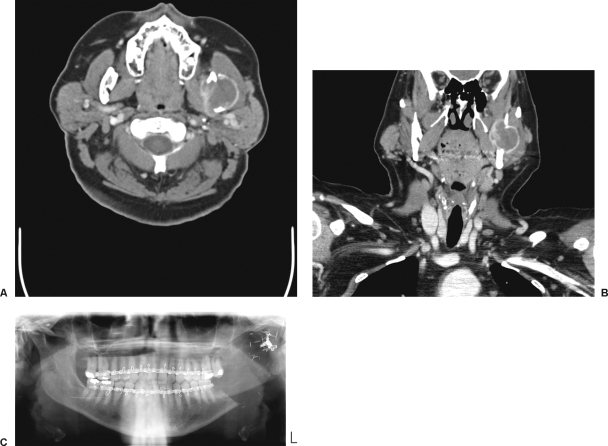

Figure 7.

(A–C) Patient with a high-grade angiosarcoma of the mandible. Patient underwent resection via a transfacial, transparotid approach. No immediate reconstruction was performed due to patient's refusal of blood product transfusion. Left mandible disarticulated. Patient functioned without formal reconstruction and does not desire definitive reconstruction. (A) Axial CT. (B) Coronal CT. (C) Postoperative panoramic radiograph of mandible.

MAXILLA AND MIDFACIAL DEFECTS

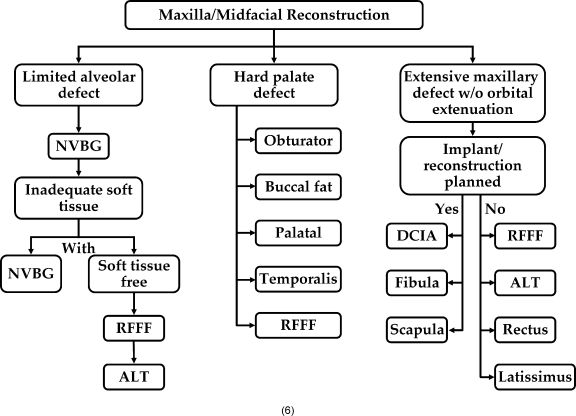

Defects of the upper midface with or without the orbit pose a significant challenge to the reconstructive surgeon. The midpoint is the central area of the face; however, it is an area of tremendous structural integrity for the facial skeleton. For an optimal aesthetic result, it is imperative for a reconstruction to occur in a three-dimensional relationship. The microvascular free flap such as the iliac crest, scapula, and fibula can be used for reestablishing bone support. The use of vascularized bone flaps for midfacial reconstruction allows the placement of osseointegrated dental implants if desired.9 Hard or soft palate defects that do not compromise the alveolus do not necessarily require bone reconstruction and may be obliterated with a local regional flap such as temporalis, buccal, or tongue flaps. The radial forearm fasciocutaneous free flap is thin and pliable and has excellent results in intraoral and oropharyngeal soft tissue reconstruction (Fig. 8).9,34 Commonly used flaps for composite midfacial reconstruction include the iliac crest, scapula, and free fibula. Nonvascularized bone grafting may also be used, but in patients irradiated or with significant mucosal loss this option is more prone to failure. For alveolar segment and for alveolar midfacial and orbital defects, the use of the prosthetic obturator without formal hard- or soft-tissue reconstruction also continues to be an excellent choice with relatively low morbidity. Composite midfacial defects are well suited to reconstruction with the deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA) free flap with internal oblique providing a dense curvilinear bone that tends to mimic the shape of the native maxilla.9,34 This has substantial bone volume to allow for placement of endosteal dental implants. The overlying muscular bed can also be sewn to the native oral mucosa and will eventually mucosalize. The free fibula free flap is less ideal for maxillary defects due to the need to form a curvilinear arch and is typically associated with a larger mobile skin paddle that tends to be slightly more unreliable than is the DCIA free flap for maxillary reconstruction.35,36 For limited composite defects, the authors have reported use of the medial femoral periosteal free flap for limited alveolar bone and mucosal reconstruction (Fig. 9).37

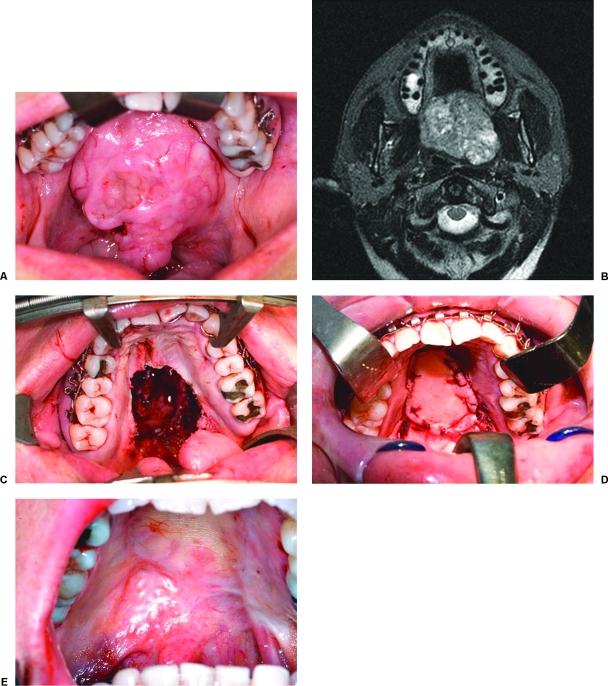

Figure 8.

(A) Patient with a large pleomorphic adenoma of the palate left untreated for several years. Patient was unwilling to wear a prosthetic obturator and therefore underwent resection with immediate reconstruction with radial forearm fasciocutaneous free flap. This provided restoration of anatomic form with excellent functional results. (B) Axial CT showing large mass in the palatal and lateral pharyngeal space. (C) Transoral maxillectomy allowing unblocked tumor removal with postoperative defect. (D) Radial forearm free flap inset for defect reconstruction. (E) Six month postoperative appearance of the palate.

Figure 9.

(A) Limited alveolar defect secondary to ballistic injury with insufficient soft tissue envelope to allow nonvascularized bone grafting. (B) Reconstructed with medial femoral periosteal free flap. (C) Delayed placement of osseointegrated dental implants into flap. Note the periosteal payer was inset to the oral mucosa and allowed to mucosalize over a period of 6 weeks. (D) Postoperative panorex showing incorporation of bone.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this article has outlined the various reconstructive options that are commonly used in contemporary reconstructive head and neck surgery. The algorithms presented provide a simple schematic approach for facial reconstruction. However, it is important for the reconstructive surgeon to be mindful of the needs of the patient and perform an operation that will provide a durable and functional result, keeping with the patient's wishes for prosthetic reconstruction. Generally, any reconstructive surgery should use the least complicated technique offering the patient the greatest chance of success, with restoration of pre-resection form and function.

There are a wide range of reconstructive options for composite hard tissue defects. Depending on the particulars of the defect, planned outcome, the patient's tolerance for donor-site morbidity, and the individual surgeon's training and experience, several methods of reconstruction may be available. In general, the best option is the simplest one that will enable all the functional and aesthetic goals of reconstruction to be met.

REFERENCES

- Gilbert A. Vascularized transfer of the fibula shaft. Int J Microsurg. 1979;1:100. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert A, Teot L. The free scapular flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:601–604. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo D. Fibula free flap; a new method of mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester W. Immediate reconstruction of the mandible and the TMJ. Br J Plast Surg. 1965;18:291–303. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(65)80050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Miller D FJH. The free vascularized bone graft: a clinical extension of microvascular techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:533–544. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urken M. Composite free flaps in oromandibular reconstruction; a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:724–732. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870190036009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Chen H, Chuang C, Nordroff M. Fibular osteocutaneous flap: anatomic study and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:191–200. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kademani D, Keller E. Iliac crest grafting for mandibular reconstruction. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2006;14:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J S. Deep circumflex iliac artery free flap with internal oblique muscle as a new method of immediate reconstruction of maxillectomy defect. Head Neck. 1996;18:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199609/10)18:5<412::AID-HED4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Seah C, Tsai Y, Liu S. Fibula osetoseptocutaneous flap for reconstruction of composite mandibular defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:294–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S, Enepekides D J. The role of distraction osteogenesis in mandibular reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:197–201. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282495925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eski M, Turegun M, Deveci M, Gokce H S, Sengezer M. Vertical distraction osteogenesis of fibular bone flap in reconstructed mandible. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57:631–636. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000235452.87390.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich R E, Schmelzle R. Distraction osteogenesis of a fibula free flap used for mandibular reconstruction: preliminary report Sergio Siciliano, Benoit Lengere, Henre Reychler. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1999;27:398. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0088. [comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler P, Schultze-Mosgau S, Neukam F W, Wiltfang J. Lengthening of the reconstructed mandible using extraoral distraction devices: report of five cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1400–1404. discussion 1405–1406. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000049115.87004.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesper B, Lazar F, Siessegger M, Hidding J, Zoller J E. Vertical distraction osteogenesis of fibula transplants for mandibular reconstruction—a preliminary study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30:280–285. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)90315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin L, Carrasco L, Kazemi A, Chalian A. Enhancement of the fibula free flap by alveolar distraction for dental implant restoration: report of a case. Facial Plast Surg. 2003;19:87–94. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Degidi M, Scarano A, Piattelli A. Vertical distraction osteogenesis of fibular free flap in mandibular prosthetic rehabilitation: a case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta R P, Deschler D G. Mandibular reconstruction in 2004: an analysis of different techniques. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:288–293. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000131444.50445.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortakoglu K, Suer B T, Ozyigit A, Ozen T, Sencimen M. Vertical distraction osteogenesis of fibula transplant for mandibular reconstruction: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e8–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siciliano S, Lengele B, Reychler H. Distraction osteogenesis of a fibula free flap used for mandibular reconstruction: preliminary report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:386–390. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(98)80072-3. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhang Z. Reconstruction of mandible with fibular flap and dental implant distractor: a new approach. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115:1877–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi B, Ferrari S, Poli T, Bertolini F, Raho T, Sesenna E. Oromandibular reconstruction with simultaneous free flaps: experience on 10 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2003;23:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H C, Demirkan F, Wei F C, Cheng S L, Cheng M H, Chen I H. Free fibula osteoseptocutaneous-pedicled pectoralis major myocutaneous flap combination in reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:839–845. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkan F, Wei F C, Chen H C, Chen I H, Liao C T. Oromandibular reconstruction using a third free flap in sequence in recurrent carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:429–433. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng S F, Kuo Y R, Wei F C, Su C Y, Chien C Y. Reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects with large lip involvement by using double free flaps and fascia lata grafts for oral sphincters. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1830–1836. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000164688.44223.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzon W M, Jr, Jejurikar S, Wilkins E G, Swartz W M. Double free-flap reconstruction of massive defects involving the lip, chin, and mandible. Microsurgery. 1998;18:372–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1998)18:6<372::aid-micr6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posch N A, Mureau M A, Dumans A G, Hofer S O. Functional and aesthetic outcome and survival after double free flap reconstruction in advanced head and neck cancer patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:124–129. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000263656.67904.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F C, Demirkan F, Chen H C, Chen I H. Double free flaps in reconstruction of extensive composite mandibular defects in head and neck cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoning H, Emshoff R. Primary temporary AO plate reconstruction of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:667–672. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo D A. Titanium miniplate fixation in free flap mandible reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23:498–507. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo D A. Fibula free flap: a new method of mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo D A. Condyle transplantation in free flap mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:770–781. discussion 782–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J P, Haribhakti V, Loree T, Sutaria P. Complication of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1990;160:352–355. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutar D S, Scheker L, Tanner N, McGregor I. The radial forearm free flap: a versatile method for intraoral reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disa J J, Pusic A L, Hidalgo D H, Cordeiro P G. Simplifying microvascular head and neck reconstruction: a rational approach to donor site selection. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:385–389. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200110000-00004. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futran N D, Haller J R. Considerations for free-flap reconstruction of the hard palate. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:665–669. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kademani D, Moran S. Medial femoral periosteal free flap. A novel method of maxillary reconstruction. Int. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:1057. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]