Abstract

Arabinan polysaccharide side-chains are present in both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Corynebacterium glutamicum in the heteropolysaccharide arabinogalactan (AG), and in M. tuberculosis in the lipoglycan lipoarabinomannan (LAM). This study shows by quantitative sugar and glycosyl linkage analysis that C. glutamicum possesses a much smaller LAM version, Cg-LAM, characterized by single t-Araf residues linked to the α(1→6)-linked mannan backbone. MALDI-TOF MS showed an average molecular mass of 13 800–15 400 Da for Cg-LAM. The biosynthetic origin of Araf residues found in the extracytoplasmic arabinan domain of AG and LAM is well known to be provided by decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-arabinose (DPA). However, the characterization of LAM in a C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant devoid of prenyltransferase activity and devoid of DPA-dependent arabinan deposition into AG revealed partial formation of LAM, albeit with a slightly altered molecular mass. These data suggest that in addition to DPA utilization as an Araf donor, alternative pathways exist in Corynebacterianeae for Araf delivery, possibly via an unknown sugar nucleotide.

INTRODUCTION

The Corynebacterianeae represent a distinct and unusual group within Gram-positive bacteria, with the most prominent members being the human pathogens Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae (Bloom & Murray, 1992). Non-pathogenic bacteria also belong to this taxon, such as Corynebacterium glutamicum, which is used in the industrial production of amino acids (Sahm et al., 2000) . These bacteria collectively belong to the same suborder, and share a similar genome, cell envelope and corresponding cell wall biosynthetic enzymes (Dover et al., 2004; Stackebrandt et al., 1997).

The characteristic cell envelope of this distinct group of bacteria contains mycolic acids, arabinogalactan (AG) and peptidoglycan, which are covalently linked to each other to form the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP) complex (Besra et al., 1995; Brennan & Nikaido, 1995; Brennan, 2003; Daffé et al., 1990; Dmitriev et al., 2000; Dover et al., 2004; McNeil et al., 1990, 1991). In addition, they possess an array of cell-wall-associated glycolipids, such as phosphatidyl-myo-inositol (PI), phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIMs) and the lipoglycans lipomannan (LM) and lipoarabinomannan (LAM) (Brennan & Ballou, 1967, 1968; Chatterjee et al., 1991, 1993; Guerardel et al., 2002; Hill & Ballou, 1966; Khoo et al., 1995). As a result, arabinose is present in two polysaccharides with markedly different structures. The occurrence of arabinosyl-containing glycoconjugates in bacteria (Brennan & Nikaido, 1995), plants (Fincher et al., 1983) and protozoan parasites (Dobson et al., 2003; Goswami et al., 2006; Guha-Niyogi et al., 2001; Previato et al., 1982; Xavier Da Silveira et al., 1998) and their absence in mammalian cells is well known. Corynebacterianeae arabinan is an extremely complex homopolymer of d-arabinofuranose (d-Araf) residues based on discrete structural motifs; however, the complete structures and biosynthesis of these polymers are still to be established.

For LAM biosynthesis we initially proposed the following biosynthetic pathway PI→PIM→LM→LAM (Besra et al., 1997) in M. tuberculosis, which is now largely supported by biochemical and genetic evidence (Gurcha et al., 2002; Kordulakova et al., 2002; Kremer et al., 2002; Schaeffer et al., 1999). PimA catalyses the addition of Manp provided by GDP-mannose to the 2-position of the myo-inositol of PI to form PIM1 (Kordulakova et al., 2002), whereas PimB might be responsible for the addition of a second Manp to the 6-position to yield Ac1PIM2 (Schaeffer et al., 1999; Tatituri et al., 2007). PimC has been demonstrated to allow further mannosylation to Ac1PIM3 (Kremer et al., 2002) and more recently, PimE has been shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of Ac1PIM5 (Morita et al., 2006). It has been proposed that PIM4 is the direct precursor of LM, characterized by a linear α(1→6)-linked mannan backbone linked with α(1→2) mannopyranose side chains generated through a mannosyltransferase encoded by Rv2181 (Kaur et al., 2006). LM is then further glycosylated with arabinan to produce LAM, and finally ‘mannose-capped’ to produce ManLAM, a process initiated by the capping enzyme encoded by Rv1635c (Dinadayala et al., 2006). For the addition of arabinose residues into mycobacterial LAM, EmbC is required (Berg et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2003), whereas AftA, EmbA and EmbB perform arabinan polymerization in AG (Alderwick et al., 2006b; Belanger et al., 1996; Escuyer et al., 2001). In contrast, C. glutamicum possesses a singular Emb, and an AftA orthologue, which are used in AG biosynthesis (Alderwick et al., 2005, 2006b; Seidel et al., 2007). It is interesting to note that the arabinan domains of AG and LAM utilize several different Araf linkages, which suggests that additional arabinofuranosyltransferases must be required to form AG and LAM, and still remain to be identified in Corynebacterianeae.

It has been shown that the activated Araf sugar donor in Corynebacterianeae is decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-arabinose (DPA) (Wolucka et al., 1994). It was also proposed that decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-ribose (DPR) could be an additional precursor involved in arabinan synthesis, via a 2′-epimerase (Wolucka & de Hoffmann, 1995). Recently, it was shown that 5-phosphoribofuranose pyrophosphate (pRpp) is converted to decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-5-phosphoribose (DPPR) via a 5-phospho-α-d-ribose-1-diphosphate-decaprenyl-phosphate 5-phosphoribosyltransferase (UbiA; Rv3806c and NCgl2781 in M. tuberculosis and C. glutamicum, respectively) (Huang et al., 2005), which is then dephosphorylated to form DPR. DPR is then enzymically oxidized to form a keto-intermediate, DPX, followed by an enzymic reduction to DPA (Mikusova et al., 2005). Additionally, disruption in C. glutamicum of ubiA, encoding the first enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of DPA, resulted in a complete loss of cell wall arabinan (Alderwick et al., 2006a). To date, no sugar nucleotides of Araf have been identified. The key discovery that Araf residues in AG arise from DPA also raised the question whether mycobacteria neither produce nor require Araf sugar nucleotides. Herein, we now clearly show that an ubiA-disrupted mutant of C. glutamicum still produces a modified LAM variant (Cg-LAM), which is arabinosylated even in the absence of the sugar donor DPA (Alderwick et al., 2006a). Taken together, the data suggest that alternative pathways may exist in Corynebacterianeae, independent of DPA utilization, specifically involved in arabinosylation events in Cg-LAM biosynthesis.

METHODS

Strains, construction of plasmids and culture conditions.

C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (the wild-type strain, referred to for the remainder of the text as C. glutamicum) and Escherichia coli DH5αmcr were grown in Luria–Bertani broth (Difco) at 30 °C and 37 °C, respectively. The C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant was grown on the complex medium brain heart infusion (Difco). Kanamycin and ampicillin were used at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1. The vector used for inactivation of C. glutamicum : : ubiA was pCg : : ubiA. It contained an internal ubiA fragment of 321 bp amplified with the primer pairs ATC TTC AAC CAG CGC ACG ATC and AAT ATC GAT CAC TGG CAT GTG, which was ligated into the SmaI site of the non-replicative vector pK18mob to yield pCg : : ubiA. To enable chromosomal inactivation of ubiA, pCg : : ubiA was introduced into C. glutamicum by electroporation (Alderwick et al., 2005).

Extraction and purification of lipoglycans.

Purification procedures were adapted from protocols established for the extraction and purification of mycobacterial lipoglycans (Nigou et al., 1999). Briefly, 10 g of cells grown to an OD600 of 1.0, were delipidated at 60 °C by using 500 ml CHCl3/CH3OH (1 : 1, v/v). The delipidated cells were resuspended in deionized water and disrupted by probe sonication (MSE Soniprep 150, 12 μm amplitude, 60 s on, 90 s off for 10 cycles, on ice) and the cell debris refluxed five times with 100 ml C2H5OH/H2O (1 : 1, v/v) at 68 °C, for 12 h intervals. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant containing lipoglycans, neutral glycans and proteins dried. The dried supernatant was then treated with a hot 80 % (w/w) phenol/H2O biphasic wash at 70 °C for 1 h, followed by several protease treatments, and the lipoglycan fraction was recovered following extensive dialysis against deionized water (Nigou et al., 1999).

The crude lipoglycan extract was resuspended in buffer A (50 mM ammonim acetate and 15 % propan-1-ol) and subjected to octyl-Sepharose CL-4B hydrophobic interaction chromatography (2.5 cm×50 cm) as previously reported (Leopold & Fischer, 1993). The column was initially washed with 4 column volumes of buffer A to ensure removal of neutral glycans followed by an increasing gradient of propan-1-ol ranging from 25 to 65 %, keeping the concentration of ammonium acetate constant. The eluates were collected and extensively dialysed against deionized water, concentrated to approximately 1 ml and precipitated using 5 ml C2H5OH; the sample was freeze-dried using a Savant SpeedVac. The freeze-dried sample containing the retained material from the hydrophobic interaction column was then resuspended in buffer B (0.2 M NaCl, 0.25 %, w/v, sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8) to a final concentration of 200 mg ml−1. The sample was gently mixed and left to incubate for 48 h at room temperature. The sample was then loaded onto a Sephacryl S-200 column (2.5 cm×50 cm) previously equilibrated with buffer B. The sample was washed with 400 ml buffer C (0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8) at a flow rate of 3 ml h−1, collecting 1.5 ml fractions using a Bio-Rad auto-sampler. The fractions were monitored by SDS-PAGE using either a silver stain utilizing periodic acid and silver nitrate (Hunter et al., 1986) or a Pro-Q emerald glycoprotein stain (Invitrogen), and individual fractions were pooled and dialysed extensively against buffer C for 72 h with frequent changes. The samples were further dialysed against deionized water for 48 h with frequent changes of deionized water, lyophilized and stored at −20 °C.

Glycosyl composition and linkage analysis of lipoglycans by alditol acetates.

Lipoglycans from wild-type C. glutamicum and the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant were hydrolysed using 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), reduced with NaBD4, and the resultant alditols were per-O-acetylated and examined by GC (Tatituri et al., 2007). Lipoglycans (2 mg) were per-O-methylated using dimethyl sulfinyl carbanion as described previously (Alderwick et al., 2005; Besra et al., 1995; Daffé et al., 1990). In this procedure, lipoglycan samples (2 mg) were resuspended in 0.5 ml DMSO (anhydrous) and 100 μl of 4.8 M dimethyl sulfinyl carbanion. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h and then iodomethane (50 μl) was slowly added and the suspension stirred for 1 h; this process was repeated for a total of three times. The reaction mixture was then diluted with an equal volume of water, dialysed against deionized water and dried. The resulting retentate was applied to a pre-equilibrated C18 Sep-Pak cartridge and initially washed with 10 ml water, 10 ml 20 % acetonitrile, and the per-O-methylated lipoglycan eluted with 2 ml acetonitrile and 2 ml ethanol. After drying the combined organic eluate under nitrogen, the per-O-methylated lipoglycan was hydrolysed using 250 μl 2 M TFA at 120 °C for 2 h. The resulting hydrolysate was reduced with NaBD4, per-O-acetylated and examined by GC/MS (Tatituri et al., 2007). Per-O-methylation of lipoglycans for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) analysis was performed as described previously (Dell et al., 1993). Briefly, 1 ml of a DMSO/NaOH slurry was added followed by 0.5 ml of iodomethane. The reaction mixture was vigorously shaken for 10 min at room temperature and the reaction quenched with 1 ml water. Per-O-methylated samples were then extracted into chloroform (1 ml) and washed several times with water before drying under a stream of nitrogen.

GC and GC/MS analysis.

Analysis of partially per-O-methylated, per-O-acetylated alditol acetate sugar derivatives was performed on a CE Instruments ThermoQuest Trace GC 2000. Samples were injected in the split mode. The column used was a DB225 (Supelco). The oven was programmed to hold at an isothermal temperature of 275 °C for a run time of 15 min. GC/MS was carried out on a BPX5 column (Supelco) and a Finnigan Polaris/GCQ PlusTM, as described previously (Besra et al., 1995; Daffé et al., 1990). GC/MS analysis of alditol acetate sugar derivatives was performed on a Perkin Elmer Clarus 500 instrument. Samples were injected in the splitless mode. The column used was an RTX-5 (30 m×0.25 mm internal diameter, Restek Corp.). Initial temperature was set at 60 °C then ramped to 300 °C at 8 °C min−1.

NMR spectroscopy.

NMR spectra of lipoglycans were recorded on a Bruker DMX-500 equipped with a double-resonance (1H/X)-BBi z-gradient probe head. All samples were exchanged in D2O (D, 99.97 %; Euriso-top), with intermediate lyophilization, and then dissolved in 0.5 ml D2O and analysed at 313 K. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts were referenced relative to internal acetone at 2.225 and 34.00 p.p.m., respectively. All the details concerning NMR sequences used and experimental procedures were described in previous studies (Gilleron et al., 1999, 2000; Nigou et al., 1999).

MALDI-MS analysis.

MALDI-MS was performed using a PerSeptive Biosystems Voyager DE STR mass spectrometer. Native lipogycans were dissolved in CH3OH/H2O (50 : 50, v/v) and 1 μl of the sample was loaded onto a metal plate. After evaporation, 1 μl of the matrix 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid was added on the spot. Samples were analysed using the linear negative mode. Per-O-methylated samples were dissolved in CH3OH/H2O (80 : 20, v/v) and analysed in the linear positive mode using 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid as matrix. Sequazyme peptide mass standards (Applied Biosystems) were used as external calibrants.

RESULTS

Disruption of Cg-ubiA

The ubiA gene product was shown in prior work to synthesize DPPR, which is converted to DPA, thus supplying the substrate for the ‘priming’ arabinosyltransferase AftA (Alderwick et al., 2006b). These initial Araf residues ‘prime’ the galactan backbone for further attachment of α(1→5)-linked Araf residues. These reactions require the arabinofuranosyltransferase activities of Mt-EmbA and Mt-EmbB, or Cg-Emb, respectively, and also the utilization of DPA (Alderwick et al., 2005; Escuyer et al., 2001; Seidel et al., 2007), to eventually result in mature AG. In light of our present studies demonstrating the occurrence of Cg-LAM we inactivated the mycobacterial orthologue of C. glutamicum, NCgl2781, by transforming the wild-type to kanamycin resistance conferred by the vector-borne aph gene product of pCg : : ubiA with a view to generating a clear C. glutamicum LM-only phenotype. The vector, as previously described (Alderwick et al., 2005), was integrated into the chromosomal ubiA gene, thus disrupting ubiA, as confirmed by two independent PCR analyses with two different primer pairs (Alderwick et al., 2005). As expected, the resulting strain C. glutamicum : : ubiA exhibited strongly reduced growth (Alderwick et al., 2006a).

Purification of lipoglycans from C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum : : ubiA

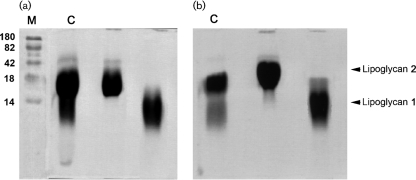

Analysis of the crude phenol-extracted lipoglycans from C. glutamicum (Fig. 1a) and C. glutamicum : : ubiA (Fig. 1b) visualized on SDS-PAGE revealed two closely migrating lipoglycans. A two-step purification protocol was performed to fractionate the crude lipoglycans. In the first step, the neutral glycans and nucleic acids were eliminated by using an octyl-Sepharose CL-4B column (Amersham Biosciences). In the second step, the lipoglycans were individually purified using a Sephacryl S-200 column (Amersham Biosciences). Fractions containing the lipoglycans were monitored by SDS-PAGE stained with either silver nitrate or Pro-Q emerald glycoprotein stains and pooled accordingly to afford lower (1) and upper (2) lipoglycans (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Lipoglycan profiles of wild-type C. glutamicum (a) and C. glutamicum : : ubiA (b). Lipoglycans were analysed using SDS-PAGE and visualized using the Pro-Q emerald glycoprotein stain (Invitrogen) specific for carbohydrates. Individual lipoglycans (1 and 2) were purified as described in Methods. C, crude lipoglycan; M, molecular mass markers (kDa).

General structural features of lipoglycans from C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum : : ubiA

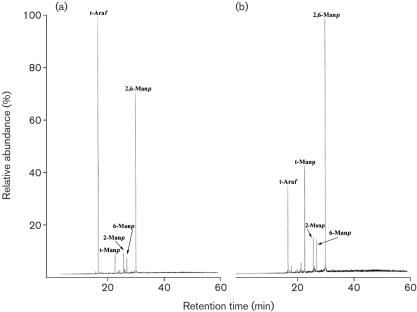

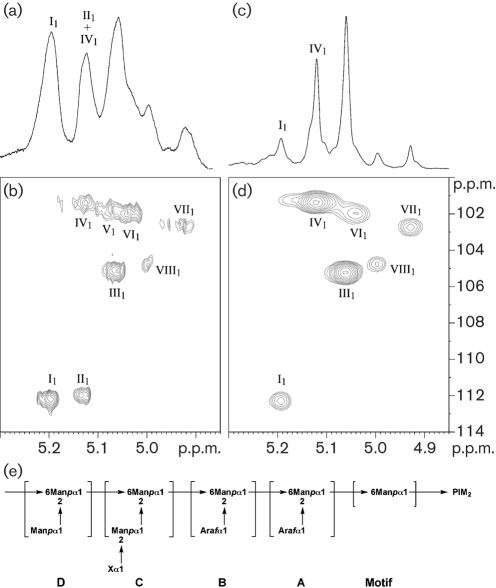

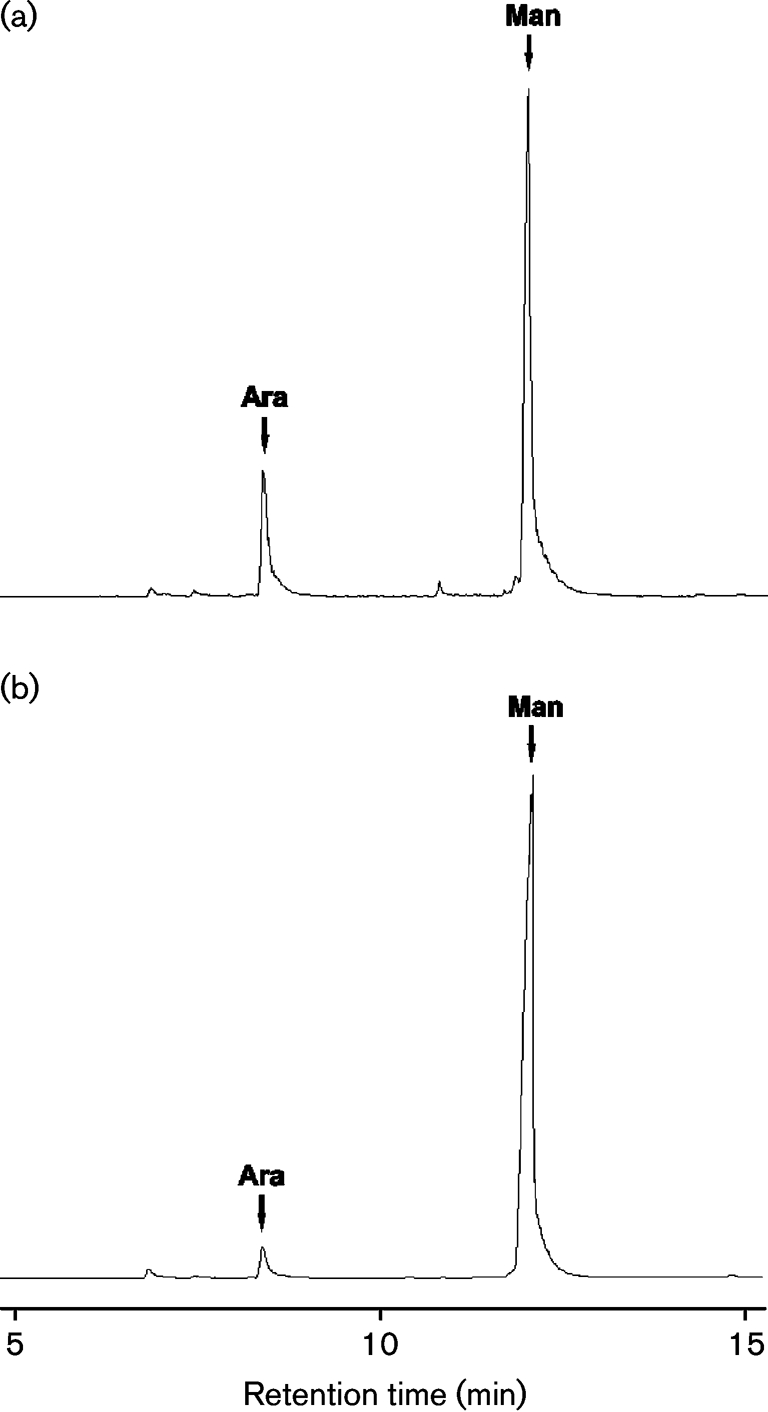

The lower lipoglycans (1) from both C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum : : ubiA were similar and exhibited the basic components of a structure related to mycobacterial LM (now termed Cg-LM) and contained solely mannopyranose (Manp). Per-O-methylation analysis of Cg-LM from both strains indicated the presence of t-Manp, 2-Manp, 6-Manp and 2,6-Manp residues (Tatituri et al., 2007). GC analysis of the total acid-hydrolysed upper lipoglycan (2) from C. glutamicum showed that it contained arabinose and mannose in a ratio of 23 : 77 and was related to mycobacterial LAM (Fig. 2a). Per-O-methylation analysis of wild-type Cg-LAM indicated the presence of t-Araf, t-Manp, 2-Manp, 6-Manp and 2,6-Manp residues (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, Cg-LAM of the wild-type strain was previously shown to be composed of a PI anchor linked to an α(1→6)Manp backbone substituted at most of the O-2 positions by the structural motifs t-Araf, t-Manp, t-Araf(1→2)-Manp and t-Manp(1→2)-Manp units (Fig. 4e) (Tatituri et al., 2007). Accordingly, the 1D 1H-NMR anomeric region (Fig. 4a) exhibited a complex pattern of overlapping resonances corresponding to Araf and Manp units. The different spin systems were characterized by 1H-13C HMQC NMR (Fig. 4b) and anomeric resonances were attributed as follows: δH1C15.20/112.2 (I1) to two overlapping t-Araf units (see below) and 5.13/112.0 (II1) to a third t-Araf unit, 5.06/105.2 (III1) to t-Manp units, 5.12/101.4 (IV1), 5.07/101.7 (V1) and 5.04/101.9 (VI1) to 2,6-Manp units, 5.06/105.2 (VII1) to 6-Manp units, and 5.00/104.9 (VIII1) to 2-Manp units.

Fig. 2.

Glycosyl compositional analysis of lipoglycan-2 from wild-type C. glutamicum (a) and C. glutamicum : : ubiA (b). Samples of individually purified lipoglycans (2) were hydrolysed with 2 M TFA, reduced and per-O-acetylated. Alditol acetates were subjected to GC analysis. Peak area integration shows that the arabinose content is 23 % in wild-type C. glutamicum (a) and 4.5 % in the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant (b). Ara, arabinose; Man, mannose.

Fig. 3.

Glycosyl linkage analysis of per-O-methylated lipoglycan-2 from C. glutamicum (a) and C. glutamicum : : ubiA (b). Lipoglycan 2 from C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum : : ubiA was per-O-methylated, hydrolysed using 2 M TFA, reduced, and per-O-acetylated. The resulting partially per-O-methylated and per-O-acetylated glycosyl derivatives were analysed by GC/MS as described previously (Alderwick et al., 2005).

Fig. 4.

(a–d) NMR characterization of wild-type Cg-LAM (a, b) and Cg-LAM from the UbiA mutant (c, d). 1D 1H (a, c) and 2D 1H-13C HMQC (b, d) NMR spectra of Cg-LAMs in D2O at 313 K. Expanded regions (δ 1H: 4.85–5.30) (a, c) and (δ 1H: 4.85–5.30, δ 13C: 100–114) (b, d) are shown. Glycosyl residues are labelled in Roman numerals and their carbons and protons in Arabic. I, II, t-α-Araf; III, t-α-Manp; IV, V, VI, 2,6-α-Manp; VII, 6-α-Manp; VIII, 2-α-Manp. (e) Structural representation of Cg-LAM (Tatituri et al., 2007). Cg-LAM contains a (1→6)-Manp backbone almost completely substituted by t-Araf, t-Manp, t-Manp(1→2)-Manp and t-Araf(1→2)-Manp units. X, either a t-Araf or a t-Manp unit.

Our previous experiments demonstrated that the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant failed to synthesize DPA (Alderwick et al., 2006a) and possessed an arabinan-deficient cell wall phenotype (Alderwick et al., 2005). As a consequence, we anticipated that the Cg-LAM from the mutant would be devoid of arabinose. Surprisingly, glycosyl compositional analysis of Cg-LAM from the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant showed that it contained arabinose, albeit in substantially smaller amounts, and mannose in a ratio of 4.5 : 95.5 (Fig. 2b). Per-O-methylation analysis of Cg-LAM from the mutant indicated the presence of t-Araf, t-Manp, 2-Manp, 6-Manp and 2,6-Manp, although the relative abundance of t-Araf residues was reduced (Fig. 3b). In agreement with the glycosyl compositional and linkage analysis data indicating a reduced amount of t-Araf units, the 1D 1H anomeric region of Cg-LAM from the glutamicum : : ubiA mutant (Fig. 4c) was simpler than that observed for Cg-LAM from wild-type C. glutamicum (Fig. 4a). Resonance I1, corresponding to a t-α-Araf unit, was dramatically reduced, suggesting two overlapping t-Araf signals. This was further confirmed by 1H-13C HMQC analysis (Fig. 4d). Indeed, the relative intensity of the correlation at δH1C15.20/112.2 (I1) was much weaker and correlation at δH1C1 5.13/112.0 (II1) of the third t-Araf residue was absent.

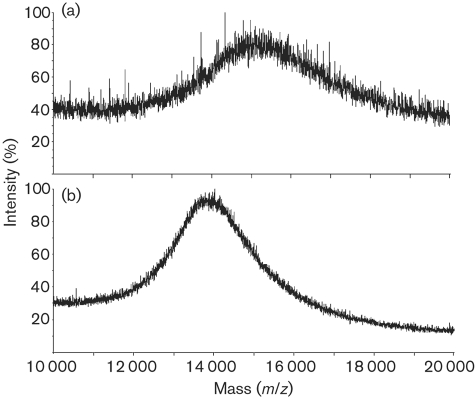

The native Cg-LAMs from wild-type C. glutamicum and the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant were analysed by MALDI TOF MS. MALDI spectra were performed in the linear negative mode. The mass spectra show broad unresolved molecular ion envelopes due to the heterogeneity of the Cg-LAMs and the relatively low resolution of this type of MS. The native Cg-LAM from wild-type C. glutamicum shows an average molecular mass of around 15 400 Da (Fig. 5a). The native Cg-LAM from the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant shows a somewhat lower average molecular mass in the region of 13 900 Da (Fig. 5b). Samples of Cg-LAM from wild-type C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum : : ubiA were subjected to per-O-methylation and analysed by MALDI TOF MS (data not shown). Per-O-methylation replaces fatty acyl substituents with methyl groups as well as methylating all the free hydroxyl groups. The average molecular mass of the derivatized Cg-LAM from wild-type C. glutamicum was observed around 15 600 Da, whilst the molecular mass of the corresponding Cg-LAM from C. glutamicum : : ubiA was observed around 15 200 Da.

Fig. 5.

MALDI-TOF MS spectra of Cg-LAM from wild-type C. glutamicum (a) and C. glutamicum : : ubiA (b). MALDI spectra were acquired in the linear negative mode with delayed extraction using 2,5-dihydrobenzoic acid as matrix.

Altogether, these data indicate that the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant produces a slightly truncated Cg-LAM with a severe reduction in t-Araf content but maintaining and possibly extending its mannan core. In addition, the presence of UbiA and the biosynthesis of DPA appear to be essential for the higher arabinosylation of Cg-LAM. Moreover, these findings suggest that arabinose deposition in the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant is a result of incorporation of t-Araf through another arabinose substrate, and one which is not DPA dependent.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the biosynthesis of mycobacterial arabinan is paramount to identifying potential new drug targets for the treatment of tuberculosis. However, as discussed earlier our understanding of these pathways is far from complete. In this respect, C. glutamicum is a useful tool in understanding mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis, since this organism possesses the core structural elements of Corynebacterianeae with few gene duplications, and deletion of orthologous genes, which is often lethal in mycobacterial species, is possible (Alderwick et al., 2005, 2006b; Gande et al., 2004). Specifically, the deletion of the DPA requiring arabinosyltransferase Emb in C. glutamicum resulted in a strongly abrogated arabinan domain of AG (Alderwick et al., 2005), and deletion of AftA also disabled attachment of the remaining singular t-Araf residues to galactan (Alderwick et al., 2006b). Furthermore, the loss of DPA synthesis in a C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant also resulted in the full loss of the arabinan domain in mature AG (Alderwick et al., 2005). In contrast, Cg-LM and Cg-LAM isolated from the corresponding C. glutamicum Δemb and ΔaftA mutants were similar to the wild-type glycans (data not shown). An absence of Araf residues was expected in Cg-LAM of the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant. Strikingly, a total absence of arabinan was not observed (Fig. 2), thus requiring an alternative source and mechanism of addition of this sugar which may be attributed to the presence of an uncharacterized nucleotide sugar donor in Corynebacterineae.

In contrast to mycobacteria, parasites do synthesize and utilize a sugar nucleotide to provide an activated arabinose sugar donor. Schneider et al. (1994) characterized GDP-α-d-Arap, the precursor of d-Ara in Leishmania major lipophosphoglycan. In trypanosomatids, this sugar nucleotide is believed to be synthesized in a two-step process through the combined activities of an Ara-1-kinase and GDP-Ara pyrophosphorylase, whereby arabinose is phosphorylated to form arabinose 1-phosphate and then activated to the nucleotide level by GDP-d-Arap pyrophosphorylase (Mengeling & Turco, 1999; Schneider et al., 1995). Compared with the many genes encoding glycosyltransferases in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, very little is known about those that encode arabinopyranosyltransferases. Dobson et al. (2003) identified two genes (SCA1/2) encoding arabinosyltransferases mediating scAra capping, and recently it was demonstrated by heterologous expression that Leishmania SCA1 encodes an arabinopyranosyltransferase (Goswami et al., 2006).

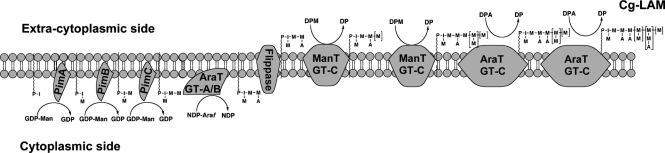

Glycosyltransferases belonging to one of the families, GT-A and GT-B, or both, may be responsible for the initial addition of t-Araf residues on to Cg-LAM in the absence of DPA. These enymes may be present on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane and probably aid in the transfer of t-Araf residues from a putative sugar nucleotide donor. These results could explain the presence of t-Araf in Cg-LAM, even though DPA biosynthesis has been completely abrogated in the C. glutamicum : : ubiA mutant (Alderwick et al., 2005). The mechanism by which these Araf residues are added is not clear. One possible explanation is that Araf residues from a nucleotide precursor are added in a step-wise fashion to Cg-LM on the cytoplasmic side to give motif A proximal to PI, and then this complex polysaccharide is then probably flipped on to the periplasmic side. It is thought that the flipping mechanism is a prerequisite for arabinosylation to occur outside of the membrane, where the arabinan and mannan domains are formed through specific GT-C glycosyltransferases, by the addition of either t-Araf and t-Manp residues, from DPA or decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-mannose (DPM) to give motifs B, C and D (Figs 4e and 6) (Berg et al., 2007; Seidel et al., 2007; Tatituri et al., 2007). The biosynthetic origin of mycobacterial Araf residues is generally a poorly understood area. To date, no sugar nucleotides of Araf have been identified, and as a result, a number of theories regarding the generation of arabinan in mycobacteria have been put forward (Huang et al., 2005; Mikusova et al., 2005; Scherman et al., 1995, 1996). Depending on the organization of the arabinan chains, it is speculated that five or six arabinofuranosyltransferases are required for arabinan biosynthesis in mycobacteria. In this regard, it is interesting to note that an M. smegmatis embC mutant (Escuyer et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2003) was found to be devoid of LAM but from the chemical analysis, the resulting LM precursor possessed two or three Araf residues. The possibility exists that these residues are initially added via a non-DPA-dependent glycosyltransferase; this requires further investigation.

Fig. 6.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of Cg-LAM. The addition of the first Araf unit is thought to occur on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane by a GT-A/B glycosyltransferase (Liu & Mushegian, 2003). After transportation across the membrane by an unknown ‘flippase’ enzyme, further elaboration of the lipoglycan then occurs through the addition of mannose and arabinose units catalysed by several GT-C glycosyltransferases utilizing DPM and DPA, respectively (Berg et al., 2007; Seidel et al., 2007; Tatituri et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

R. V. V. T. and A. K. M. are Darwin Trust sponsored PhD students. G. S. B. acknowledges support in the form of a Personal Research Chair from Mr James Bardrick, as a former Lister Institute-Jenner Research Fellow, and from the Medical Research Council and The Wellcome Trust. A. D. and H. R. M. are supported by funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. A. D. is a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Professorial Research Fellow.

Abbreviations

Ac, acylated

Ara, arabinose

Araf, arabinofuranose

AG, arabinogalactan

DPA, decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-arabinose

DPM, decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-mannose

DPR, decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-d-ribose

DPPR, decaprenyl-monophosphoryl-5-phosphoribose

LAM, lipoarabinomannan

LM, lipomannan

Man, mannose

mAGP, mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan

p, pyranose

PI, phosphatidyl-myo-inositol

PIMs, phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides

pRpp, 5-phosphoribofuranose pyrophosphate

t-, terminal

TFA, trifluoroacetic acid

References

- Alderwick, L. J., Radmacher, E., Seidel, M., Gande, R., Hitchen, P. G., Morris, H. R., Dell, A., Sahm, H., Eggeling, L. & Besra, G. S. (2005). Deletion of Cg-emb in Corynebacterianeae leads to a novel truncated cell wall arabinogalactan, whereas inactivation of Cg-ubiA results in an arabinan-deficient mutant with a cell wall galactan core. J Biol Chem 280, 32362–32371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderwick, L. J., Dover, L. G., Seidel, M., Gande, R., Sahm, H., Eggeling, L. & Besra, G. S. (2006a). Arabinan-deficient mutants of Corynebacterium glutamicum and the consequent flux in decaprenylmonophosphoryl-d-arabinose metabolism. Glycobiology 16, 1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderwick, L. J., Seidel, M., Sahm, H., Besra, G. S. & Eggeling, L. (2006b). Identification of a novel arabinofuranosyltransferase (AftA) involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 281, 15653–15661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, A. E., Besra, G. S., Ford, M. E., Mikusova, K., Belisle, J. T., Brennan, P. J. & Inamine, J. M. (1996). The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 11919–11924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, S., Starbuck, J., Torrelles, J. B., Vissa, V. D., Crick, D. C., Chatterjee, D. & Brennan, P. J. (2005). Roles of conserved proline and glycosyltransferase motifs of EmbC in biosynthesis of lipoarabinomannan. J Biol Chem 280, 5651–5663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, S., Kaur, D., Jackson, M. & Brennan, P. J. (2007). The glycosyltransferases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; roles in the synthesis of arabinogalactan, lipoarabinomannan, and other glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 17, 35R–56R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besra, G. S., Khoo, K. H., McNeil, M. R., Dell, A., Morris, H. R. & Brennan, P. J. (1995). A new interpretation of the structure of the mycolyl-arabinogalactan complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through characterisation of oligoglycosylalditol fragments by fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 34, 4257–4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besra, G. S., Morehouse, C. B., Rittner, C. M., Waechter, C. J. & Brennan, P. J. (1997). Biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. J Biol Chem 272, 18460–18466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B. R. & Murray, C. J. (1992). Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science 257, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, P. J. (2003). Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 83, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, P. & Ballou, C. E. (1967). Biosynthesis of mannophosphoinositides by Mycobacterium phlei. The family of dimannophosphoinositides. J Biol Chem 242, 3046–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, P. & Ballou, C. E. (1968). Biosynthesis of mannophosphoinositides by Mycobacterium phlei. Enzymatic acylation of the dimannophosphoinositides. J Biol Chem 243, 2975–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, P. J. & Nikaido, H. (1995). The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 64, 29–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, D., Bozic, C. M., McNeil, M. & Brennan, P. J. (1991). Structural features of the arabinan component of the lipoarabinomannan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 266, 9652–9660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, D., Khoo, K. H., McNeil, M. R., Dell, A., Morris, H. R. & Brennan, P. J. (1993). Structural definition of the non-reducing termini of mannose-capped LAM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis through selective enzymatic degradation and fast atom bombardment-mass spectrometry. Glycobiology 3, 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffé, M., Brennan, P. J. & McNeil, M. (1990). Predominant structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through characterisation of oligoglycosyl alditol fragments by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and by 1H and 13C NMR analyses. J Biol Chem 265, 6734–6743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell, A., Khoo, K.-H., Panico, M., McDowell, R. A., Etienne, A. T., Reason, A. J. & Morris, H. R. (1993). FAB-MS and ES-MS of glycoproteins. In Glycobiology: a Practical Approach, pp. 187–222. Edited by M. Fukuda & A. Kobata. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dinadayala, P., Kaur, D., Berg, S., Amin, A. G., Vissa, V. D., Chatterjee, D., Brennan, P. J. & Crick, D. C. (2006). Genetic basis for the synthesis of the immunomodulatory mannose caps of lipoarabinomannan in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 281, 20027–20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev, B. A., Ehlers, S., Rietschel, E. T. & Brennan, P. J. (2000). Molecular mechanics of the mycobacterial cell wall: from horizontal layers to vertical scaffolds. Int J Med Microbiol 290, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, D. E., Mengeling, B. J., Cilmi, S., Hickerson, S., Turco, S. J. & Beverley, S. M. (2003). Identification of genes encoding arabinosyltransferases (SCA) mediating developmental modifications of lipophosphoglycan required for sand fly transmission of Leishmania major. J Biol Chem 278, 28840–28848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover, L. G., Cerdeno-Tarraga, A. M., Pallen, M. J., Parkhill, J. & Besra, G. S. (2004). Comparative cell wall core biosynthesis in the mycolated pathogens, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Corynebacterium diphtheriae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28, 225–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escuyer, V. E., Lety, M. A., Torrelles, J. B., Khoo, K. H., Tang, J. B., Rithner, C. D., Frehel, C., McNeil, M. R., Brennan, P. J. & Chatterjee, D. (2001). The role of the embA and embB gene products in the biosynthesis of the terminal hexaarabinofuranosyl motif of Mycobacterium smegmatis arabinogalactan. J Biol Chem 276, 48854–48862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincher, G. B., Stone, B. A. & Clarke, A. E. (1983). Arabinogalactan-proteins: structure, biosynthesis, and function. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 34, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gande, R., Gibson, K. J., Brown, A. K., Krumbach, K., Dover, L. G., Sahm, H., Shioyama, S., Oikawa, T., Besra, G. S. & Eggeling, L. (2004). Acyl-CoA carboxylases (accD2 and accD3), together with a unique polyketide synthase (Cg-pks), are key to mycolic acid biosynthesis in Corynebacterianeae such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 279, 44847–44857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleron, M., Nigou, J., Cahuzac, B. & Puzo, G. (1999). Structural study of the lipomannans from Mycobacterium bovis BCG: characterisation of multiacylated forms of the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol anchor. J Mol Biol 285, 2147–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleron, M., Bala, L., Brando, T., Vercellone, A. & Puzo, G. (2000). Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv parietal and cellular lipoarabinomannans. Characterisation of the acyl- and glyco-forms. J Biol Chem 275, 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, M., Dobson, D. E., Beverley, S. M. & Turco, S. J. (2006). Demonstration by heterologous expression that the Leishmania SCA1 gene encodes an arabinopyranosyltransferase. Glycobiology 16, 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerardel, Y., Maes, E., Elass, E., Leroy, Y., Timmerman, P., Besra, G. S., Locht, C., Strecker, G. & Kremer, L. (2002). Structural study of lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan from Mycobacterium chelonae. Presence of unusual components with α1,3-mannopyranose side chains. J Biol Chem 277, 30635–30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha-Niyogi, A., Sullivan, D. R. & Turco, S. J. (2001). Glycoconjugate structures of parasitic protozoa. Glycobiology 11, 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurcha, S. S., Baulard, A. R., Kremer, L., Locht, C., Moody, D. B., Muhlecker, W., Costello, C. E., Crick, D. C., Brennan, P. J. & Besra, G. S. (2002). Ppm1, a novel polyprenol monophosphomannose synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem J 365, 441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D. L. & Ballou, C. E. (1966). Biosynthesis of mannophospholipids by Mycobacterium phlei. J Biol Chem 241, 895–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H., Scherman, M. S., D'Haeze, W., Vereecke, D., Holsters, M., Crick, D. C. & McNeil, M. R. (2005). Identification and active expression of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene encoding 5-phospho-α-d-ribose-1-diphosphate: decaprenyl-phosphate 5-phosphoribosyltransferase, the first enzyme committed to decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose synthesis. J Biol Chem 280, 24539–24543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S. W., Gaylord, H. & Brennan, P. J. (1986). Structure and antigenicity of the phosphorylated lipopolysaccharide antigens from the leprosy and tubercle bacilli. J Biol Chem 261, 12345–12351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, D., Berg, S., Dinadayala, P., Giquel, B., Chatterjee, D., McNeil, M. R., Vissa, V. D., Crick, D. C., Jackson, M. & Brennan, P. J. (2006). Biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan: Role of a branching mannosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 13664–13669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, K. H., Dell, A., Morris, H. R., Brennan, P. J. & Chatterjee, D. (1995). Inositol phosphate capping of the nonreducing termini of lipoarabinomannan from rapidly growing strains of Mycobacterium. J Biol Chem 270, 12380–12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordulakova, J., Gilleron, M., Mikusova, K., Puzo, G., Brennan, P. J., Gicquel, B. & Jackson, M. (2002). Definition of the first mannosylation step in phosphatidylinositol mannoside synthesis. PimA is essential for growth of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 277, 31335–31344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, L., Gurcha, S. S., Bifani, P., Hitchen, P. G., Baulard, A., Morris, H. R., Dell, A., Brennan, P. J. & Besra, G. S. (2002). Characterisation of a putative α-mannosyltransferase involved in phosphatidylinositol trimannoside biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem J 363, 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, K. & Fischer, W. (1993). Molecular analysis of the lipoglycans of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Anal Biochem 208, 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. & Mushegian, A. (2003). Three monophyletic superfamilies account for the majority of the known glycosyltransferases. Protein Sci 12, 1418–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, M., Daffe, M. & Brennan, P. J. (1990). Evidence for the nature of the link between the arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan of mycobacterial cell walls. J Biol Chem 265, 18200–18206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, M., Daffe, M. & Brennan, P. J. (1991). Location of the mycolyl ester substituents in the cell walls of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 266, 13217–13223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengeling, B. J. & Turco, S. J. (1999). A high-yield, enzymatic synthesis of GDP-d-[3H]arabinose and GDP-L-[3H]fucose. Anal Biochem 267, 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikusova, K., Huang, H., Yagi, T., Holsters, M., Vereecke, D., D'Haeze, W., Scherman, M. S., Brennan, P. J., McNeil, M. R. & Crick, D. C. (2005). Decaprenylphosphoryl arabinofuranose, the donor of the d-arabinofuranosyl residues of mycobacterial arabinan, is formed via a two-step epimerisation of decaprenylphosphoryl ribose. J Bacteriol 187, 8020–8025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Y. S., Sena, C. B., Waller, R. F., Kurokawa, K., Sernee, M. F., Nakatani, F., Haites, R. E., Billman-Jacobe, H., McConville, M. J. & other authors (2006). PimE is a polyprenol-phosphate-mannose-dependent mannosyltransferase that transfers the fifth mannose of phosphatidylinositol mannoside in mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 281, 25143–25155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigou, J., Gilleron, M. & Puzo, G. (1999). Lipoarabinomannans: characterisation of the multiacylated forms of the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol anchor by NMR spectroscopy. Biochem J 337, 453–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previato, J. O., Mendonca-Previato, L., Lewanczuk, R. Z., Travassos, L. R. & Gorin, P. A. (1982). Crithidia spp.: structural comparison of polysaccharides for taxonomic significance. Exp Parasitol 53, 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahm, H., Eggeling, L. & de Graaf, A. A. (2000). Pathway analysis and metabolic engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biol Chem 381, 899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, M. L., Khoo, K. H., Besra, G. S., Chatterjee, D., Brennan, P. J., Belisle, J. T. & Inamine, J. M. (1999). The pimB gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a mannosyltransferase involved in lipoarabinomannan biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 274, 31625–31631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman, M., Weston, A., Duncan, K., Whittington, A., Upton, R., Deng, L., Comber, R., Friedrich, J. D. & McNeil, M. (1995). Biosynthetic origin of mycobacterial cell wall arabinosyl residues. J Bacteriol 177, 7125–7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman, M. S., Kalbe-Bournonville, L., Bush, D., Xin, Y., Deng, L. & McNeil, M. (1996). Polyprenylphosphate-pentoses in mycobacteria are synthesized from 5-phosphoribose pyrophosphate. J Biol Chem 271, 29652–29658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P., McConville, M. J. & Ferguson, M. A. (1994). Characterization of GDP-alpha-d-arabinopyranose, the precursor of D-Arap in Leishmania major lipophosphoglycan. J Biol Chem 269, 18332–18337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P., Nikolaev, A. & Ferguson, M. A. (1995). The biosynthesis of GDP-d-arabinopyranose in Crithidia fasciculata: characterization of a d-arabino-1-kinase activity and its use in the synthesis of GDP-[5-3H]d-arabinopyranose. Biochem J 311, 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, M., Alderwick, L. J., Sahm, H., Besra, G. S. & Eggeling, L. (2007). Topology and mutational analysis of the single Emb arabinofuranosyltransferase of Corynebacterium glutamicum as a model of Emb proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Glycobiology 17, 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L., Berg, S., Lee, A., Spencer, J. S., Zhang, J., Vissa, V., McNeil, M. R., Khoo, K. H. & Chatterjee, D. (2006). The carboxy terminus of EmbC from Mycobacterium smegmatis mediates chain length extension of the arabinan in lipoarabinomannan. J Biol Chem 281, 19512–19526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt, E., Rainey, F. A. & Ward-Rainey, N. L. (1997). Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 47, 479–491. [Google Scholar]

- Tatituri, R. V., Illarionov, P. A., Dover, L. G., Nigou, J., Gilleron, M., Hitchen, P., Krumbach, K., Morris, H. R., Spencer, N. & other authors (2007). Inactivation of Corynebacterium glutamicum NCgl0452 and the role of MgtA in the biosynthesis of a novel mannosylated glycolipid involved in lipomannan biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 282, 4561–4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka, B. A. & de Hoffmann, E. (1995). The presence of β-d-ribosyl-1-monophosphodecaprenol in mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 270, 20151–20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolucka, B. A., McNeil, M. R., de Hoffmann, E., Chojnacki, T. & Brennan, P. J. (1994). Recognition of the lipid intermediate for arabinogalactan/arabinomannan biosynthesis and its relation to the mode of action of ethambutol on mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 269, 23328–23335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier Da Silveira, E., Jones, C., Wait, R., Previato, J. O. & Mendonca-Previato, L. (1998). Glycoinositol phospholipids from Endotrypanum species express epitopes in common with saccharide side chains of the lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania major. Biochem J 329, 665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N., Torrelles, J. B., McNeil, M. R., Escuyer, V. E., Khoo, K. H., Brennan, P. J. & Chatterjee, D. (2003). The Emb proteins of mycobacteria direct arabinosylation of lipoarabinomannan and arabinogalactan via an N-terminal recognition region and a C-terminal synthetic region. Mol Microbiol 50, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]