Abstract

Objectives

1) To determine the degree of discordance between patient and physician assessment of disease severity in a multiethnic cohort of adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 2) to explore predictors of discordance, and, 3) to examine the impact of discordance on the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS 28).

Methods

Two hundred and twenty-three adults with RA and their rheumatologists completed a visual analogue scale (VAS) for global disease severity independently. Patient demographics, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) depression scale, HAQ score, and DAS 28 were also collected. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify predictors of positive discordance, defined as a patient rating minus physician rating of ≥ 25 mm on a 100 mm VAS (considered clinically relevant). DAS 28 stratified by level of discordance was compared using a paired t-test.

Results

Positive discordance was found in 31% of cases with a mean difference of 46 ± 15. The strongest independent predictor of discordance was a 5-point increase in PHQ-9 (AOR 1.64; 95% CI, 1.06 – 2.53). Higher swollen joint count and Cantonese/Mandarin language were associated with lower odds of discordance. DAS scores were most divergent among subjects with discordance.

Conclusion

Nearly one third of RA patients differed from their physicians to a meaningful degree in assessment of global disease severity. Higher depressive symptoms were associated with discordance. Further investigation of the relationships between mood, disease activity, and discordance may guide interventions to improve care for adults with RA.

Introduction

Accurate assessments of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are central to establishing disease severity and monitoring response to treatment. With the advent of increasingly effective yet potentially toxic therapies, the need for patient-provider agreement or “concordance” around assessments of disease activity is critical to the safe and effective management of RA. These assessments which rely on both subjective (patient self-report) and objective measures (physician-assessed joint counts, acute phase reactants) pose a significant challenge to the field of rheumatology.

While diseases such as diabetes or hypertension have objective, numerical measures to assess severity and treatment response (hemoglobin A1c or blood pressure), RA disease activity lacks a single gold standard. Composite scores such as the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS 28) (1) are routinely used in clinical trials but less commonly used in practice. One key component of the DAS 28 is the patient global assessment of disease severity as measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS). Given that new American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommendations (2) include a disease activity score to determine eligibility for non-biologic and biologic therapies in RA, the patient global assessment will need to be collected more systematically in practice.

Support for the clinical value of concordance can be found in non-rheumatic chronic conditions, where studies show that when doctors and patients agree, adherence and outcomes improve (3). Despite the importance of concordance in assessments of disease activity, little is known about the prevalence and correlates of discordance, or disagreement, around commonly used measures in RA. The ACR core set of disease activity measures includes both patient and physician global assessment of disease severity (4). Discordance between physicians and patients on these measures as well as other measures of health status have been reported previously in RA(5, 6). While these results, among others, show that discordance exists (6–10), there is a paucity of research to help us understand why such a gap exists. The studies which examined discordance in RA identified patient age, gender and education level as being associated with discrepancies in assessments, but did not evaluate the possible association of patients’ language or mood with discordance both of which pose barriers to communication and have been associated with variation in symptom reporting(11, 12). Language barriers have also been associated with lower patient satisfaction, poorer health outcomes and increased mortality in a number of chronic conditions (13–16), but have not been studied in RA. Co-morbid depression in chronic disease states has been linked to underestimation of symptoms by physicians and suboptimal communication, but a similar association has not been examined in RA (17, 18).

While discordance in RA has been documented, no study has sought to better understand this phenomenon in an ethnically diverse population which includes non-English speaking patients, nor evaluated the impact of depressed mood on agreement. In addition, no study has yet examined the effect of discordance on the DAS 28. Therefore, our study had three objectives. The first was to determine the degree and directionality of discordance between patients’ and physicians’ assessment of global disease severity in an ethnically diverse cohort of adults with RA. The second was to explore pre-specified, patient-level predictors of any measured discordance of disease severity. The final objective was to examine the impact of discordance on the scoring and categorization of disease activity by the DAS 28.

Patients and Methods

Study population

Subjects were participants in the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort, a multi-site observational cohort. Enrollment began in October 2006. Subjects were consecutively enrolled from two outpatient clinics staffed by UCSF faculty and fellows, the Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) and the university-based UCSF Arthritis Center. Subjects included in this study must have been seen by a rheumatologist at one of these sites at least twice over a previous 12-month period, be ≥ 18 years of age, and meet the 1987 ACR criteria for RA (19). Physician participants were board-certified or board eligible rheumatologists based in the two clinics, including fellows-in-training. The research protocol was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. All participants gave their informed consent to be part of the study.

Variables

Bilingual research associates gathered data on patient demographics, disease characteristics, functional status and depressive symptom scores in the clinics. Patient demographics included age, gender, ethnicity, language, and country of origin, and were obtained at time of enrollment in the cohort. Disease characteristics included rheumatoid factor status and disease activity as captured by a 28 tender and swollen joint count recorded by the physician, a sedimentation rate, and full DAS 28 calculated after each visit. Functional status was measured using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (20). Since this measure has been shown to be stable over a one-year period, it was included in this study if obtained within one year of the patient and physician global scores (20). The HAQ is scored 0–3 with “0” being no disability and “3” being severe disability.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) (21). The PHQ-9, the recommended measure to screen for depression in primary care settings, is a validated and reliable screening measure available in English, Spanish and Chinese (22, 23). The PHQ-9 has a range of scores from 0 to 27. Scores of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, and ≥ 20 correspond to none, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depressive symptoms, respectively. We treated the PHQ-9 as a continuous variable with 5-point increments that correspond to none, mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depressive symptoms.

Measure of patient-physician discordance

The primary outcome of this study was the mean of the difference between patient and physician scores on the visual analogue scale (VAS) for global disease severity. The patient and physician global VAS was recorded at each clinical visit. Prior to the visit, each patient was asked the following question in English, Spanish, or Chinese: “Considering all the ways that your arthritis affects you, rate how you are doing on the following scale by placing a vertical mark (|) on the line.” The line is a 0–100 mm horizontal line where 0 = “very well” and 100 = “very poor.” After the visit, the physician (blinded to patient results) marked a separate line using the same 100 mm scale. For the purposes of this study, we used the patient and physician VAS scores from the first recorded cohort visit where data were complete for all measures listed above. Patient and physician ratings were compared by measuring the difference between the two VAS scores (3, 5, 6, 17, 24, 25). In addition to measuring the degree of discordance, we also assessed the direction. For example, if the patient rated herself with worse disease severity than the physician, we termed this “positive discordance,” as subtracting a physician score that was lower than the patient’s resulted in a positive integer. In the instance where a physician marked disease severity as worse than the patient, we termed this “negative discordance.”

A one-sample t-test was used to assess the mean of the difference between patient and physician scores on the VAS for global disease severity. While no standardized cut-off for a level of clinically significant discordance exists in the literature, prior research suggests that a difference of 25mm on a 0–100mm scale is considered clinically meaningful (3). In addition, there is a literature which supports that an approximation of the minimal clinically important difference is on average equal to one half a standard deviation (26). For the purposes of this study, we used ≥ 25mm of difference as the cut-off for discordance. Given the lack of uniformity regarding a clinically significant degree of discordance, we also performed sensitivity analyses using cut offs of 10mm and 40mm.

Bivariable analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize differences in patient demographics, disease characteristics and depressive symptoms between the concordant and discordant groups. Specifically, bivariable relationships between discordance and patient’s age (continuous), race/ethnicity, language (Spanish, English, Cantonese/Mandarin or other), country of origin (U.S. vs. non-U.S. born), and gender were assessed. Bivariable relationships between discordance and other disease characteristics (including rheumatoid factor status, physician-recorded tender and swollen joint counts, DAS 28 and HAQ scores) were also assessed. The relationship between discordance and depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9 (continuous) was also assessed. We used chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables.

Multivariable analysis

We used a multivariate logistic regression analysis to measure the independent effects of patient demographics, disease characteristics and depressive symptoms on discordance. As has been done in a prior study (17), subjects with negative discordance defined as lower than −25mm difference (n=12), were included in the non-discordant group because of the small number, and models were run with and without this group. In the multivariate model, we included those covariates that were significant at P<0.20 in the bivariate analyses. Clinic site, patient age, gender and language were also included in the multivariable analysis because they may affect doctor-patient communication, and therefore discordance, despite or because of the presence of in-person or video-monitor interpreter services. Finally, we used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering by physician.

Additional Analyses: Discordance and the Disease Activity Score 28

In order to explore how patient-physician discordance in assessment of disease activity may affect the DAS 28 and categorization of severity (low, moderate, high), we compared mean DAS 28 scores between concordant and positive discordant pairs both with (DAS 28 4-variable) and without (DAS 28 3-variable) the patient global on a subgroup (n=202) with complete data to calculate a DAS 28. To determine if discordance was associated with differences between an individuals’ DAS 28 4-variable score and a modified DAS 28 3-variable (calculated without the patient global assessment, see note to Table 3 for formulas), subjects were first separated into two groups: no discordance and positive discordance. Paired t-tests were then used to compare DAS 28 4-variable and DAS 28 3-variable scores. The DAS 28 4-variable and the DAS 28 3-variable were then categorized according to standard cut-offs for disease severity (≤ 3.2 = low, >3.2 and ≤ 5.1 = moderate, > 5.1 = high) and stratified by concordant vs. positive discordant groupings. All analyses were performed using STATA Version 9.2 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

Table 3.

DAS 28 4 variable compared to DAS 28 3-variable by degree of discordance

| No discordance (<25mm) |

Positive discordance (≥ 25 mm) |

Negative Discordance (< −25mm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=132) | (n=59) | (n=11) | |

| DAS 28 4-v, mean | 4.01 ± 1.53 | 4.31 ± 1.53 | 4.66 ± 1.23 |

| DAS 28 3-v, mean | 3.93 ± 1.40 | 3.77 ± 1.50 | 4.86 ± 1.32 |

| Difference between DAS 28 4- v and DAS 28 3-v |

0.08 | 0.54 | −0.21 |

| p-value, paired t-test | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

DAS = Disease Activity Score

Please note the following formulas used to calculate the DAS 28 4-variable and DAS 28 3-variable, respectively:

DAS28 = 0.56 * sqrt(tender28) + 0.28 * sqrt(swollen28) + 0.70 * ln(ESR) + 0.014 * GH

DAS28(3) = (0.56*sqrt(t28) + 0.28*sqrt(sw28) + 0.70*Ln(ESR))*1.08 + 0.16

Results

Demographics, clinical characteristics

Data from 223 consecutively enrolled subjects with complete data were included in this analysis. The mean age was 53 ± 14 years. Eighty-eight percent were female and 45% were Latino, 27% Asian / Pacific Islander, 16% White, 10% African American and 2% American Indian or Other. Nearly three-quarters of the subjects were born outside of the U.S. (Table 1). With regard to clinical characteristics, 83% were rheumatoid factor positive with a median swollen joint count of 3 (inter-quartile range or IQR 1, 8) and a median tender joint count of 1 (IQR 0, 6). The mean HAQ score was 1.27 ± 0.82. The mean PHQ-9 score was 7.08 ± 5.80. Sixty-six subjects (30%) met the definition of moderate to severe depression on the PHQ-9 (score ≥ 10). The mean patient VAS score for global disease severity was 46 ± 26 and the mean physician VAS score was 31 ± 21. The mean of the difference in VAS scores was 16 ± 26.

Table 1.

Characteristics of UCSF RA cohort (n=223), stratified by level of discordance (none = ≤25mm difference; positive = > 25 mm; negative < −25mm)

| Total N=223 |

No discordance N=143 |

Positive Discordance N=68 |

Negative Discordance N=12 |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|||||

| Age, years | 53 ± 14 | 53 ± 14 | 53 ± 13 | 47 ± 14 | 0.35 |

| Female | 197 (88) | 125 (87) | 62 (91) | 10(83) | 0.56 |

| Ethnicity | 0.71 | ||||

| Latino | 101 (45) | 59 (41) | 36 (53) | 6 (50) | |

| African American | 23 (10) | 14 (10) | 7 (10) | 2(17) | |

| Asian / Pacific Islander |

60 (27) | 44 (31) | 13 (19) | 3(25) | |

| White | 35 (16) | 23 (16) | 11 (16) | 1(8) | |

| American Indian or Other |

4 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Language | 0.66 | ||||

| English | 85 (38) | 57 (40) | 25 (37) | 4 (33) | |

| Spanish | 86 (39) | 50 (35) | 30 (44) | 5 (42) | |

| Cantonese/ Mandarin |

39 (17) | 28 (19) | 8 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| Other | 13 (6) | 8 (6) | 5 (7) | 0 | |

| Clinic site | 0.92 | ||||

| County Hospital | 177 (79) | 112 (78) | 55 (81) | 10 (83) | |

| University | 46 (21) | 31 (22) | 13 (19) | 2 (17) | |

| Country of Origin | 0.19 | ||||

| USA | 59 (26) | 43 (30) | 15 (22) | 1 (8) | |

| Non-USA | 164 (74) | 100 (70) | 53 (78) | 11 (92) | |

| RF positive | 185 (83) | 117 (82) | 57 (84) | 11 (92) | 0.79 |

| Swollen joint count, median (IQR) |

3 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 8) | 1 (0, 5) | 11 (7, 18) | <0.001 |

| Tender joint count, median (IQR) |

1 (0, 6) | 1 (0, 4) | 1 (0, 7) | 4 (0, 8) | 0.61 |

| Patient Global | 46.19±26.29 | 37.34±23.26 | 69.21 ±17.47 | 21.25 ±11.62 | <0.001 |

| Physician Global | 30.50±21.06 | 31.03 ±21.35 | 23.43 ±14.55 | 64.29 ±14.79 | <0.001 |

| Patient Global - Physician Global |

15.69±26.00 | 6.31 ±11.23 | 45.78 ±14.53 | −43.04 ± 5.17 | <0.001 |

| HAQ* | 1.27±0.82 | 1.14±0.82 | 1.55±0.76 | 1.30±0.81 | 0.003 |

| PHQ-9** score | 7.08±5.80 | 5.83±4.77 | 9.50±6.73 | 8.25±7.13 | 0.001 |

| Depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) |

66 (30) | 33 (23) | 29 (43) | 4 (33) | 0.013 |

HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire

PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9

Patient-physician discordance of global disease severity

A patient-physician difference of ≥ 25mm on the VAS for global disease severity (patient scores worse than physician, or “positive” discordance) was found in 68 of the patient-physician dyads (31%) with a mean difference of 46 ± 15. Twelve of the dyads (5%) had less than −25 mm (patient scores less severe than physician, or “negative” discordance) with a mean difference of −43 ± 15. In 143 dyads (64%), there was < 25mm of difference on the VAS scores (corresponding to no discordance or “concordance”) with a mean difference of 6 ± 11.

Predictors of discordance

The results of the bivariable analysis (Table 1) revealed significant differences among the groups by discordance status with regard to swollen joint count (p <0.001), depressive symptoms (PHQ-9, p= 0.002), and functional status (HAQ, p= 0.003). Poorer function, greater depressive symptoms, and fewer swollen joints were more common among subjects with positive discordance. Language category was not statistically significantly different between the groups (p=0.663).

On multivariable analyses (Table 2), depressive symptoms as recorded by a 5-point increase in the PHQ-9 score were an independent predictor of positive discordance (AOR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.02 – 2.55). The swollen joint count was associated with decreased odds of discordance (AOR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83 – 0.91). Cantonese/Mandarin language was also associated with lower odds of discordance (AOR 0.44, 95% CI 0.28 – 0.69) as compared to English, the referent group. In multivariable models, the association between poorer functional status (HAQ) and discordance persisted as measured by the point estimate, but was no longer statistically significant (AOR 1.71, 95% CI 0.82 – 3.55).

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression of predictors of discordance between patient and physician assessments of global disease severity

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval (CI) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio* |

95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 0.98 –1.02 | 0.99 | 0.97 – 1.02 |

| Female | 1.53 | 0.59 – 4.00 | 1.03 | 0.34 – 3.18 |

| Language | ||||

| English | - | - | - | - |

| Spanish | 1.11 | 0.58 – 2.10 | 1.06 | 0.63 – 1.79 |

| Cantonese/Mandarin | 0.57 | 0.23 –1.40 | 0.44† | 0.28 – 0.69 |

| Other | 1.38 | 0.41 – 4.61 | 1.52 | 0.89 – 2.59 |

| Country of Origin | ||||

| USA | 0.71 | 0.36 – 1.40 | ||

| Non-USA | - | - | ||

| RF positive | 1.09 | 0.51 – 2.35 | ||

| Swollen joint count | 0.92 | 0.86 – 0.98 | 0.87† | 0.83 – 0.91 |

| Tender joint count | 1.03 | 0.98 – 1.08 | ||

| Sedimentation rate | 1.00 | 0.98 – 1.01 | ||

| HAQ* | 1.85 | 1.28 – 2.68 | 1.71 | 0.82 – 3.55 |

| 5-point increase in PHQ-9** |

1.67 | 1.29 – 2.15 | 1.62† | 1.02 – 2.55 |

Adjusted OR includes age, gender, clinic site, language, HAQ score, swollen joint count and 5-point increase in PHQ-9 and accounts for clustering by physician.

p <0.05;

HAQ* = Health Assessment Questionnaire;

PHQ-9** = Patient Health Questionnaire 9

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses using cutoffs of 10mm and 40mm, 55% and 18% respectively of the patient-physician dyads resulted in the patient scoring higher than the physician (positive discordance). Only one-third (33%) of the pairs were concordant using the 10mm cutoff as opposed to the majority of pairs (79%) using the 40mm cut-off.

Further sensitivity analyses yielded similar results to the original analyses in that greater depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), worse functional status (HAQ), and a lower swollen joint count were all significant predictors of discordance in unadjusted analyses for the 10mm and 40mm cut-offs. However, in the multivariate logistic regression using the 10mm cut-off, worse functional status was associated with greater odds of discordance and English language was associated with lower odds of discordance. The 40-mm cut-off did not yield statistically significant predictors in multivariate analysis but showed similar patterns to both the 10mm and 25mm cut-offs.

Exploratory analysis of multivariable results

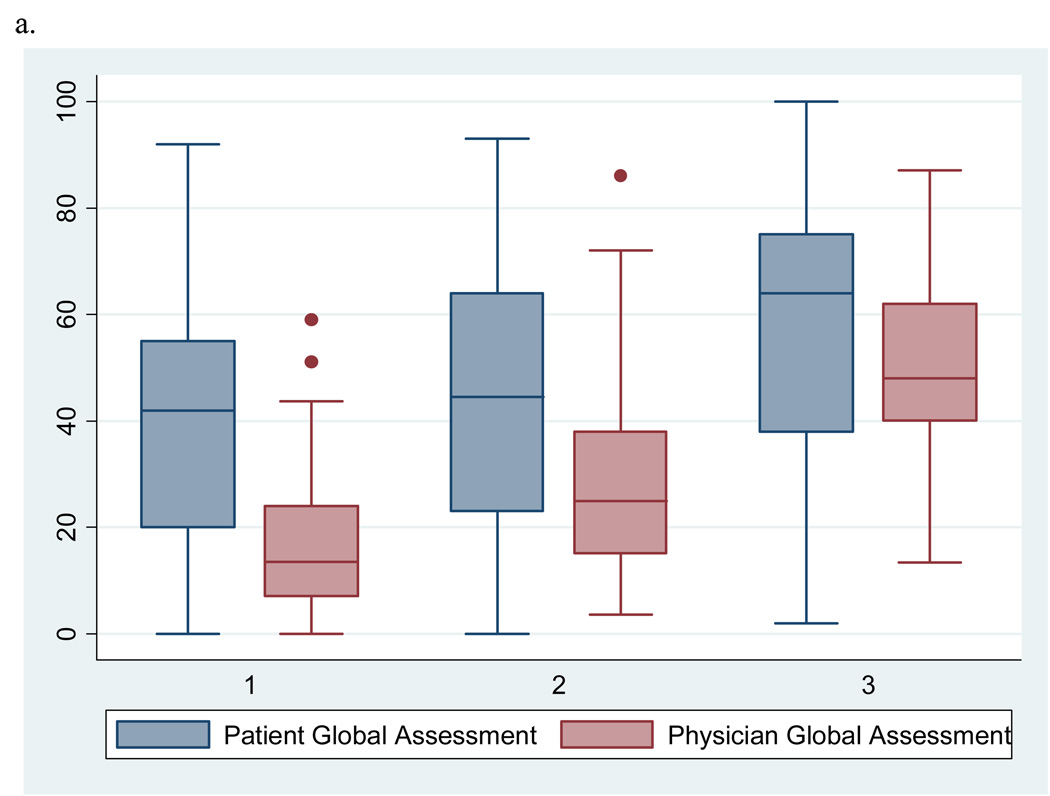

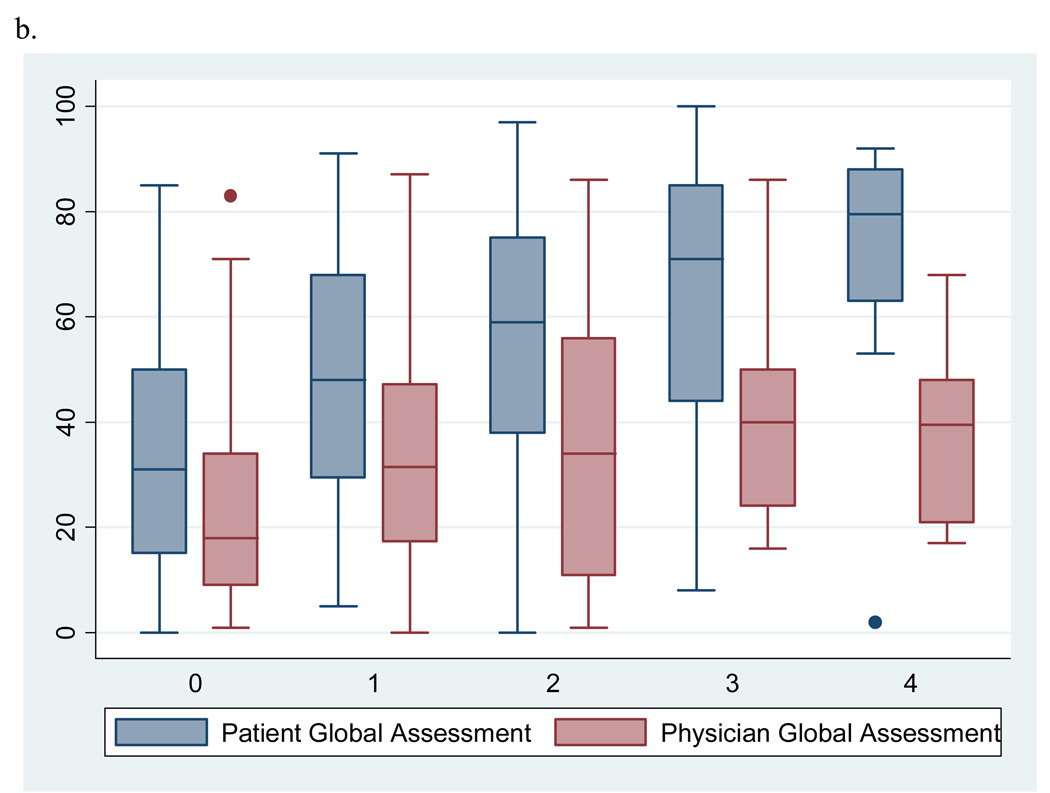

To help interpret our findings, we explored which of the two components of the outcome (patient or physician global VAS score) drives the observed associations of two significant predictors with discordance. Figure 1a illustrates side by side box plots of patient and physician global VAS scores by tertile of swollen joint counts. The mean physician global VAS score increases steadily with each tertile of swollen joint counts. In addition, the largest discrepancy in mean global VAS scores is seen at the lowest tertile of swollen joint counts and appears to narrow as the counts increase suggesting there may be a threshold of swollen joints at which patients and physicians begin to agree. In Figure 1b, the mean patient global VAS score increases steadily with each increase in category of depressive symptoms while mean physician global scores appear to remain relatively stable.

Figure 1.

a. Side by side box plots of patient and physician global assessments for disease activity by tertile of swollen joint counts

b. Side by side box plots of patient and physician globals by category of depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9 scale (0 = no depression; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = moderate to severe; 4 = severe)

Discordance and the Disease Activity Score 28

Complete data to calculate the DAS 28 was available for 202 subjects. The mean DAS 28 for the concordant pairings (n=132) was 4.01 ± 1.53; positive discordant pairings (n=59), 4.31 ± 1.53; and negative discordant pairings (n=11), 4.66 ± 1.23. There was a statistically significant difference between the mean DAS 28 4-variable and the DAS 28 3-variable (which does not include the patient global) scores for all groups (Table 3). The largest difference between the two scores was seen among patients with positive discordance (DAS 28 3-variable was 0.54 lower on average for the positive discordant subjects vs. 0.08 for the concordant subjects). The differences between the DAS 28 4-variable and DAS 28 3-variable also revealed variation in how subjects were categorized into low, moderate, or high levels of disease activity. For instance, while 15 subjects in the positive discordance group (n=59) were classified as having low disease activity using the DAS 28 4-variable, using the DAS 28 3-variable led to only 25 being classified in the low disease activity group. Subjects in general move from a higher disease activity level to a lower one when using the DAS 28 3-variable (data not shown). These shifts were most pronounced in the positive concordance group.

Discussion

In this study, we found evidence for clinically meaningful differences between patient and physician assessments of RA disease activity in 36% of cases. Physician assessments under scored patients’ assessments in the overwhelming majority (85%) of discordant pairs. The presence of greater depressive symptoms was an independent predictor, while a higher swollen joint count was associated with lower odds of discordance. These findings were robust across different cut-points for discordance. As the threshold of discordance was lowered, however, we found that worse functional status and non-English language were independently associated with discordance. An exploration of our findings revealed that mean patient global assessments increased with higher depressive symptoms while mean physician global scores remained similar. In contrast, the mean patient and physician global assessments were least discordant at the highest tertile of swollen joint counts. Among subjects with positive discordance (patient scores worse than physician), mean DAS 28 scores calculated with and without the patient global were most divergent. This important finding suggests that among patients who are discordant with their physicians, the DAS 28 score may not accurately reflect disease activity.

Discrepancies between patient and professional assessments of pain, function, and overall health have been reported in RA (5–7, 9, 10, 27). Nicolau et al. evaluated differences in ratings of disease activity using a 3 cm cutoff on a 10 cm VAS and found a difference in 37%, an effect nearly identical to that in our study (5). Suarez-Almazor, et al. explored discordance in ratings of health status, and reported, as in our study, physicians on average rated their patients’ health as better than did patients. The impact of language or psychological well-being on discordance was not reported (6). Our finding of Chinese language being associated with decreased odds of discordance may be a statistical artifact, or perhaps related to the quality of the Chinese language interpreter in our clinics.

The impact of depression on symptom reporting in RA has been well-documented (28). Zautra et al. found an association between recurrent bouts of major depression and increased risk for pain (29). While depression has been shown to be associated with more pain and worse function (30), there is no literature in RA that explores the role of depression and its association with discordance. Depression has been associated with symptom underestimation by physicians in non-rheumatic diseases (17). In one study of adult diabetics screened for depression, Swenson et al found that patients with severe depressive symptoms were more likely to report suboptimal clinician-patient communication (18). The authors hypothesized that this could be due to competing demands, unmet expectations, or poor concentration related to depression. It is possible that the association between depressive symptoms and discordance observed in our study is a result of poor communication for any of the aforementioned reasons. Given the prevalence of co-morbid depression and RA (31), the mechanisms for how depressive symptoms are associated with discordance warrants further investigation.

Finally, and perhaps most notably, no study has evaluated the effect of discordance on the DAS 28. In our study, the largest mean difference between the DAS 28 4-variable and the DAS 28 3-variable (calculation without the patient global) was seen in patients with positive discordance. One explanation may be related to an association of depressive symptoms and discordance. Higher disease activity as measured by the DAS 28 may reflect both a patient’s mood as well as disease activity. Ward found that self-report of pain and global disease severity may be confounded by depression (32). Our analysis indicates that depressive symptoms are associated with positive discordance, which, in turn, may impact the DAS 28. If this is in fact true, rheumatologists (as guided by ACR recommendations to aim for low disease activity) may escalate therapy for patients whose apparent moderate or high disease activity as reflected by the DAS 28 is influenced more by depressed mood than by systemic inflammation, joint pain or swelling. In such cases, appropriate recognition and treatment of depressive symptoms may be warranted. Alternatively, depressive symptoms may be an emotional manifestation of the systemic, inflammatory process common in RA and depressed mood may, in part, be driven by heightened levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines postulated in the literature (33).

A third explanation may be that depression somehow interferes with the efficacy of therapy in RA and blunts the response as measured through the components of the DAS 28. A recent study by Hider and colleagues to investigate the prevalence of depression among RA patients initiating anti-TNF therapy reported a high prevalence of depression (47.5%) as well as a higher mean DAS 28 among depressed patients at baseline prior to treatment, and at 3 and 12 months while on therapy (34). Depressed patients had a poorer response to anti-TNF therapy with smaller reductions in all components of the DAS 28 when compared to non-depressed patients at 3 months. This study has several limitations. First, our study population was largely non-White (83%), non-U.S. born (78%), and from an urban area. While this may limit the generalizability of our findings, it could also be viewed as a strength insofar as vulnerable populations have been shown to be at greater risk of miscommunication with physicians, experience lower quality of care, and less commonly participate in research studies (35–40). Second, we measured depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9 rather than the gold standard of a clinical diagnostic interview. The PHQ-9, however, has been shown to be a reliable and valid screening measure of depression severity in the outpatient setting (21). Third, this was a cross-sectional study and, as such, a causal relationship between depressive symptoms and discordance cannot firmly be established; nor can we assess whether discordance lessens over time. Fourth, there are no established cut-points for what constitutes “significant” discordance in the literature, but it should be noted that 25 mm exceeds a half standard deviation of discordance (26mm) which approximates a minimal clinically important difference (26). In addition, we performed sensitivity analyses which supported our findings. As we accrue longitudinal data and perform additional analyses, we will examine in greater depth the relationship between depressive symptoms and discordance. Finally, there were no direct observations of patient-physician communication during clinic visits or a measure of quality of the doctor-patient relationship which could have provided additional insights as to contributors of discordance. Potential next steps in better understanding why discordance exists could include a qualitative study to explore how beliefs and/or culture may influence the reporting of disease severity by both patients and physicians and, an evaluation of the role of health literacy as a potential predictor of discordance.

In conclusion, we found that 36% of RA patients differed from their physicians to a clinically meaningful degree with physicians systematically under-scoring disease severity relative to patients’ self-assessments. Depressive symptoms were common, with 30% of subjects exceeding a cut-point of major depression. Independent predictors of discordance included greater depressive symptoms and a lower swollen joint count. In sensitivity analyses, we also found that non-English language and functional status were associated with discordance.

Future studies should prospectively evaluate the impact of discordance in disease activity assessment in RA and on the DAS 28 in particular, and assess the contribution of depressive symptoms to the quality of clinician-patient communication. In addition, reducing discordance may be an important goal in and of itself, as it has been shown that when doctors and patients agree, adherence and outcomes improve (3). Further investigation of the relationships between mood, disease activity, and discordance may help guide interventions to improve care for adults with RA.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Barton, Imboden, Graf, and Yelin’s work was supported by funding from the American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation’s Within Our Reach program and by the Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis, University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Barton’s work was also supported by a Physician Scientist Development Award from the American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation and the Hellman Family Early Career Award. Dr. Yelin’s work was also supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant P60 AR053308, Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center). Drs. Glidden and Schillinger’s work was supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–48. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762–784. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville C, Clarke AE, Joseph L, Belisle P, Ferland D, Fortin PR. Learning from discordance in patient and physician global assessments of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(3):675–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–740. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolau G, Yogui MM, Vallochi TL, Gianini RJ, Laurindo IM, Novaes GS. Sources of discrepancy in patient and physician global assessments of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(7):1293–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suarez-Almazor ME, Conner-Spady B, Kendall CJ, Russell AS, Skeith K. Lack of congruence in the ratings of patients' health status by patients and their physicians. Med Decis Making. 2001;21(2):113–121. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkanovic E, Hurwicz ML, Lachenbruch PA. Concordant and discrepant views of patients' physical functioning. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8(2):94–101. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA. Rheumatology patient and physician concordance with respect to important health and symptom status outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(4):372–377. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<372::AID-ART350>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewlett SA. Patients and clinicians have different perspectives on outcomes in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(4):877–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwoh CK, O'Connor GT, Regan-Smith MG, Olmstead EM, Brown LA, Burnett JB, et al. Concordance between clinician and patient assessment of physical and mental health status. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(7):1031–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen HT, Clark M, Ruiz RJ. Effects of acculturation on the reporting of depressive symptoms among Hispanic pregnant women. Nurs Res. 2007;56(3):217–223. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270027.97983.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Rrustemi I, Gariazzo F, Eytan A, Loutan L. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):503–512. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, Greenfield S, Massagli MP, Clarridge B, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22 Suppl 2:324–330. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarver J, Baker DW. Effect of language barriers on follow-up appointments after an emergency department visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(4):256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.06469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Stable EJ, Napoles-Springer A, Miramontes JM. The effects of ethnicity and language on medical outcomes of patients with hypertension or diabetes. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1212–1219. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardam M, Verma G, Campbell A, Wang J, Khan K. Impact of the Patient-Provider Relationship on the Survival of Foreign Born Outpatients with Tuberculosis. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zastrow A, Faude V, Seyboth F, Niehoff D, Herzog W, Lowe B. Risk factors of symptom underestimation by physicians. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(5):543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swenson SL, Rose M, Vittinghoff E, Stewart A, Schillinger D. The influence of depressive symptoms on clinician-patient communication among patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Care. 2008;46(3):257–265. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31816080e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(1):167–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The Feasibility of Using the Spanish PHQ-9 to Screen for Depression in Primary Care in Honduras. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(5):191–195. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Brooks K, Roseman JM, Fessler BJ, Sanchez ML, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XI. Sources of discrepancy in perception of disease activity: A comparison of physician and patient visual analog scale scores. Arthritis Care and Research. 2002;47(4):408–413. doi: 10.1002/art.10512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen JC, Abrahamowicz M, Dobkin PL, Clarke AE, Battista RN, Fortin PR. Determinants of discordance between patients and physicians in their assessment of lupus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(9):1967–1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter JD, Lodhi AB, Nagda SR, Ricca L, Ward C, Traina E, et al. Determining rheumatologists' accuracy at assessing functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients using the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):958–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardwell WA, Nicassio PM, Weisman MH, Gevirtz R, Bazzo D. Rheumatoid Arthritis Severity Scale: a brief, physician-completed scale not confounded by patient self-report of psychological functioning. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41(1):38–45. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zautra AJ, Parrish BP, Van Puymbroeck CM, Tennen H, Davis MC, Reich JW, et al. Depression history, stress, and pain in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Behav Med. 2007;30(3):187–197. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz PP, Yelin EH. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among persons with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(5):790–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uguz F, Akman C, Kucuksarac S, Tufekci O. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy is associated with less frequent mood and anxiety disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward MM. Are patient self-report measures of arthritis activity confounded by mood? A longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(6):1046–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiepers OJ, Wichers MC, Maes M. Cytokines and major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hider SL, Tanveer W, Brownfield A, Mattey DL, Packham JC. Depression in RA patients treated with anti-TNF is common and under-recognized in the rheumatology clinic. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(9):1152–1154. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schillinger D, Wang F, Palacios J, Rodriguez M, Machtinger EL, Bindman A. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medication in an anticoagulation clinic: a comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun. 2006;11(7):651–664. doi: 10.1080/10810730600934500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer SA, Roter DL, Higginson IJ. Chest pain: communication of symptoms and history in a London emergency department. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1–2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essen B, Bodker B, Sjoberg NO, Langhoff-Roos J, Greisen G, Gudmundsson S, et al. Are some perinatal deaths in immigrant groups linked to suboptimal perinatal care services? Bjog. 2002;109(6):677–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason S, Hussain-Gambles M, Leese B, Atkin K, Brown J. Representation of South Asian people in randomised clinical trials: analysis of trials' data. Bmj. 2003;326(7401):1244–1245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svensson CK. Representation of American blacks in clinical trials of new drugs. Jama. 1989;261(2):263–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(5):382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]