Abstract

The aim of our study was to determine whether resistance exercise-induced elevations in endogenous hormones enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy with training. Twelve healthy young men (21.8 ± 1.2 yr, body mass index = 23.1 ± 0.6 kg/m2) trained their elbow flexors independently for 15 wk on separate days and under different hormonal milieu. In one training condition, participants performed isolated arm curl exercise designed to maintain basal hormone concentrations (low hormone, LH); in the other training condition, participants performed identical arm exercise to the LH condition followed immediately by a high volume of leg resistance exercise to elicit a large increase in endogenous hormones (high hormone, HH). There was no elevation in serum growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), or testosterone after the LH protocol but significant (P < 0.001) elevations in these hormones immediately and 15 and 30 min after the HH protocol. The hormone responses elicited by each respective exercise protocol late in the training period were similar to the response elicited early in the training period, indicating that a divergent postexercise hormone response was maintained over the training period. Muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) increased by 12% in LH and 10% in HH (P < 0.001) with no difference between conditions (condition × training interaction, P = 0.25). Similarly, type I (P < 0.01) and type II (P < 0.001) muscle fiber CSA increased with training with no effect of hormone elevation in the HH condition. Strength increased in both arms, but the increase was not different between the LH and HH conditions. We conclude that exposure of loaded muscle to acute exercise-induced elevations in endogenous anabolic hormones enhances neither muscle hypertrophy nor strength with resistance training in young men.

Keywords: testosterone, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, anabolism

hormones such as testosterone, growth hormone (GH), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) are important for skeletal muscle anabolism during growth and development (e.g., 23). It has been suggested that acute elevation of this triumvirate of hormones that occurs after performance of intense resistance exercise is a significant contributor to the gains in strength and hypertrophy that are observed with resistance training (14, 19, 24, 30). The magnitude of the increase in concentration of these hormones is largely dependent on parameters of the resistance exercise. Specifically, large elevations of systemic hormones are observed acutely postexercise after resistance exercise bouts consisting of a high amount of work (8, 9, 28). Additionally, higher intensity exercise (16, 19) with short rest intervals (4, 17) that is performed with large muscle groups (10, 19) are also associated with large rises in these hormones. In fact, training principles have been constructed to maximize the postexercise rise in these hormones based on the interpretation that exercise-induced increases in systemic hormones like testosterone and GH will enhance muscle hypertrophy (15, 27, 31). Specifically, it has been suggested that small exercising muscle groups (e.g., biceps brachii), which are incapable of inducing large increases in systemic anabolic hormones when used in isolation, should be trained concurrently with large exercising muscle masses that can elevate testosterone and GH (10, 19). However, the hypothesis that exercise-induced rises in testosterone and GH enhance increases in strength and muscle hypertrophy with training remains untested.

We have previously demonstrated that acute changes in muscle protein synthesis following resistance exercise and feeding (38) can qualitatively predict gains in muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) and lean body mass (11). Recently, we have shown that exercise-induced hormones that are hypothesized to be anabolic and affect hypertrophy do not acutely enhance fed-state myofibrillar protein synthesis after acute resistance exercise (36). Despite the ability of the postexercise protein synthetic response (38) to predict phenotypic adaptations to training (11), it is unknown whether the synthetic responses that we observed after a single acute bout of exercise (36) would ultimately translate into similar increases in muscle size and strength when hormone availability is manipulated following repeated bouts of resistance exercise (i.e., training). Thus the aim of our present study was to determine if increases in muscle strength and hypertrophy are enhanced by exercise-induced increases in hormone availability with resistance training. Based on our previous acute finding that myofibrillar protein synthesis was not enhanced by acute elevations in circulating testosterone, GH, and IGF-1, we hypothesized that repeatedly elevating the acute postexercise availability of these hormones would not enhance the muscle hypertrophy and strength gains achieved from a progressive resistance training program. Previous work demonstrating an effect of elevated endogenous hormones on gains in isometric strength has used a similar design (10) . Thus, as a reasonable proof of principle study, if acute rises in GH, IGF-1, and testosterone were to result in differential phenotypic changes, then an inherently superior design for testing this thesis is a unilateral within-person design, where interindividual differences in potential for hypertrophy and strength gains, which are substantial (12), are minimized.

METHODS

Subjects.

Twelve healthy young men (21.8 ± 0.4 yr, 1.78 ± 0.02 m, 74.1 ± 3.3 kg; means ± SE) volunteered to participate in the study after being informed of the procedures and potential risks involved in the investigation. Subjects were recreationally active with no formal weightlifting experience. Participants provided consent to an agreement that was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Hamilton Health Sciences and that was written in accordance with standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental protocol.

Using a within-person design, participants trained each arm on separate days under two different hormonal environments for 15 wk. In the low hormone condition (LH), one arm performed arm curl exercise only, while in the high hormone condition (HH) the contralateral arm performed the same arm curl exercise followed immediately by a bout of leg resistance exercises designed to elicit large increases in circulating hormones. In weeks 1–6, participants trained each arm three times over 2 wk; they trained in a manner that allowed 72 h between LH and HH training days (e.g., week 1: Monday*, Tuesday, Friday*; week 2: Monday, Thursday*, Friday; HH session days shown with asterisk). This approach was taken to ensure that the enhanced muscle protein synthetic response, which can be elevated in the untrained state for ∼48 h (22, 26), occurred exclusively on the background of basal hormone concentrations during LH before the hormonal spike that was associated with exercise on the HH day 72 h later. In weeks 7–15, an extra training session was added to enhance the training stimulus so that each arm trained twice per week with at least 48 h following each arm-only trial (e.g., week 7: Monday*, Tuesday, Thursday*, Friday; HH session days shown with asterisk). We have previously shown that resistance training shortens the duration (i.e., <28 h) for which muscle protein synthesis is elevated after exercise (33). Therefore, despite the inclusion of an additional training session per week, the attenuated time course of muscle protein synthesis after exercise in a more trained state would still have provided enough recovery to ensure that the LH arm was not exposed to the hormonal milieu of HH during the skeletal muscle remodeling process. Participants consumed 18 g of whey protein immediately before exercise and 18 g at 90 min after arm exercise in each condition to support maximal rates of muscle protein synthesis both in the absence and presence of elevated hormone concentrations as well as to reduce variability in nutrition surrounding the exercise bout.

Training.

Subjects were familiarized with each exercise before strength testing and beginning the training program. Exercise in LH consisted of three to four sets of 8–12 repetitions at a load that was ∼95% of their 10-repetition maximum (RM) such that voluntary failure occurred during the final set. Exercise in HH was performed in the contralateral arm and consisted of identical arm exercise to LH but was followed by five sets of 10 repetitions of leg press and three sets of 12 repetitions of leg extension/leg curl “supersets” (1 set of each exercise, back-to-back, with no rest between sets) at ∼90% of 10 RM. Between-set rest intervals for arm and leg exercises were 120 and 60 s, respectively. Participants followed a progressive training protocol with respect to the number of sets and repetitions and to the load that was lifted. Each training session was supervised individually, and compliance across 56 sessions (28 per arm) was 96%.

Strength testing.

Isotonic 1 and 10 RMs were tested pre- and posttraining for the arm curl and leg exercises using standard procedures. Isometric maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) strength was tested using a custom dynamometer. To isolate the elbow flexors as the sole producers of force, participants were seated with their upper arm abducted in the horizontal plane and with a pad clamped firmly down on the top of their shoulder. The forearm was supinated and tightly fastened using straps on an aluminum plate that was attached to a steel shaft. The participant's arm was positioned at 120° (180° = full extension) with the elbow visually aligned with the axis of rotation. A strain gauge was used to detect torque produced by isometric elbow flexion. The signal from the strain gauge was amplified and filtered (DC to 200-Hz bandwidth) before being digitized (sample rate of 3 kHz; model DI420, Dataq Instruments, Akron, OH) and analyzed with custom LabView 7 Express software (National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Analyses.

Blood samples were taken following the third as well as the final training session to characterize the hormonal response elicited by each condition (LH and HH) both early and late in the training period. Blood samples were analyzed for serum cortisol, testosterone, GH, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and IGF-1 using solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescence immunometric assays (Immulite; Intermedico, Holliston, MA). All intra-assay coefficients of variation for these hormones were below 5%, and all assays included standards and daily quality assurance procedures. Free testosterone was calculated from total testosterone and sex hormone binding globulin (21). Lactate was measured on neutralized deproteinized whole blood using an enzymatic-colorimetric assay kit (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI). Plasma insulin concentration was determined using Coat-a-Count insulin kits (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA). Blood amino acids were analyzed by HPLC as previously described (25). Hematocrit was measured in triplicate using standard microcapillary methods. Change in plasma volume was calculated from hemoglobin concentration (cyanmethemoglobin technique, Pointe Scientific) and hematocrit using equations by Dill and Costill (7).

MRI.

Participants underwent MRI scans using a 1-T extremity scanner (OrthOne, ONI Medical Systems, Wilmington, MA) at the Centre for Appendicular MRI Studies (Hamilton, ON, Canada). Fluorescent markers were placed over the elbow joint line and 12 cm proximally; coronal and sagittal scout scans were used to locate the markers and center the region of interest in the magnetic field. Participants lay with their arm abducted and their wrist in a neutral position so that their elbow flexors were not compressed. Beginning at the joint line, 16 axial scans were taken to determine elbow flexor CSA as a function of distance from the elbow joint line. Images were acquired using the following parameters: repetition time/echo time, 700 ms/21.8 ms; field of view, 14 cm; phase/frequency, 288; slice thickness, 2 mm; gap, 6 mm. Participants' arms were scanned before the beginning of the training program and ∼72 h after the final training bout. Each image was circled three times by the same investigator using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software (version 1.38, Bethesda, MD); average coefficient of variation for measured CSA on repeated traces was 0.6%.

Muscle fiber CSA.

Muscle biopsies were performed pre- and posttraining with a 5-mm Bergström needle that was custom modified for manual suction under local anesthesia (2% xylocaine). Muscle fibers were oriented vertically under a dissecting microscope and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) medium. The mounted muscle was frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until processing for CSA analysis. Cross sections (10 μm thick) were cut, mounted on glass slides, and stained using a myofibrillar ATPase histochemisty procedure at an acid preincubation pH of 4.6 to distinguish type I and type II fibers as described previously (13, 32). Pictures of the stained slides were taken using a light microscope and NIS Elements 3.0 Imaging Software (Nikon, NY). An average of 47 type I and 53 type II fibers were circled using ImagePro Plus software (version 4.5.1.22, Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) to quantify CSA. During the course of analysis our freezer malfunctioned, which compromised the quality of some of our samples. Since the study was a within-subject design with pre- and posttraining biopsies, if one or more of four samples (pre-LH and pre-HH; post-LH and post-HH) was of poor quality it prevented us from being able to make within-subject comparisons. Thus we have only included data for subjects (n = 7) for whom we could obtain a complete data set from both arms pre- and posttraining.

Statistics.

This study was a within-subject repeated-measures design. Blood lactate and serum hormone concentrations were analyzed using three-factor repeated-measures ANOVA statistics with training (pre and post), condition (LH and HH), and time (preexercise and 0, 15, 30, and 60 min postexercise) as within-subject factors. Two-factor (training × condition) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze area under the curve data; two-factor (time × condition) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze hematocrit and plasma volume change early in the training period. One-factor (time) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze mean insulin and amino acid concentrations across training in each condition. Hypertrophy and strength data were analyzed using two-factor (training × condition) repeated-measures ANOVA. Where ANOVA revealed significance (P < 0.05), Tukey's post hoc test was used to identify pairwise differences. Values are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Blood analyses.

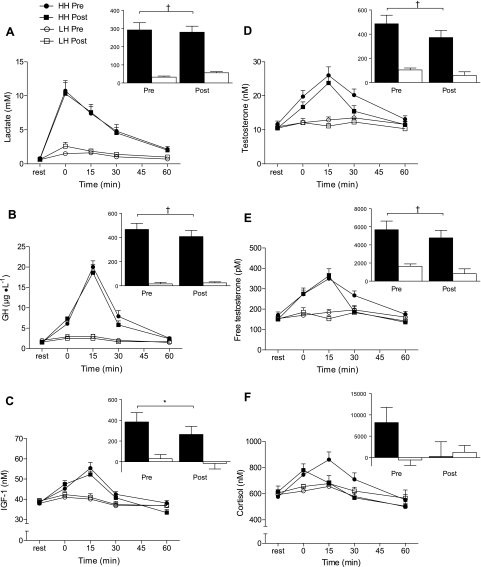

LH elicited a minimal rise in lactate concentration (∼2 mmol/l at peak), whereas HH elicited a marked increase (∼10.5 mmol/l at peak); nearly identical responses were elicited before and after training within each condition (Fig. 1A). Figure 1, B–E, shows the hormone responses of GH, IGF-1, and total and free testosterone, respectively, after each condition during the first and last weeks of training. There was no change in the concentration of any of these hormones after exercise in LH. In contrast, there was a marked increase in GH, IGF-1, and total and free testosterone that peaked ∼15 min after HH (P < 0.001); this divergent pattern in hormone availability was present both at the beginning and end of 15 wk of training. Cortisol concentrations were similar to basal levels after LH and were markedly elevated after HH; there was an attenuation of the cortisol response after HH at the end of the training period. DHEA-S exhibited a pattern broadly similar to other hormones with a significant rise at 0 and 15 min in HH compared with LH and with no training-induced changes in basal levels or in the pattern of response (data not shown). Hematocrit increased, and plasma volume decreased, to a greater extent after HH compared with after LH (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Whole blood lactate (A) and serum growth hormone (GH; B), IGF-1 (C), total testosterone (D), free testosterone (E) and cortisol (F) concentrations at rest and after low hormone (LH) and high hormone (HH) exercise protocols. Insets: net area under the curve (AUC; rest = 0); closed bars, HH; open bars, LH. Significantly greater than LH for corresponding time points and for AUC, *P < 0.01, †P < 0.001. Values are means ± SE.

Table 1.

Hematocrit and change in plasma volume

| Pretraining | Time, min |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 30 | 60 | ||

| Hematocrit, % | |||||

| HH | 43.7 ± 1.2 | 49.5 ± 1.0‡ | 46.2 ± 1.6† | 44.9 ± 1.3∗ | 45.0 ± 1.2 |

| LH | 43.1 ± 0.8 | 46.0 ± 0.9 | 43.4 ± 1.2 | 42.8 ± 1.1 | 43.4 ± 1.3 |

| Plasma volume, %Δ | |||||

| HH | −19.8 ± 1.0† | −9.1 ± 2.2 | −5.6 ± 1.4 | −5.8 ± 1.9 | |

| LH | −10.0 ± 2.8 | −4.1 ± 1.2 | −3.2 ± 2.2 | −4.8 ± 2.1 | |

Values are means ± SE. Hematocrit: there was a greater increase in hematocrit after the high hormone (HH) protocol (condition × time interaction, P < 0.001). Different from low hormone (LH) at same time: ∗P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001. Plasma volume: there was a greater decrease in plasma volume after the HH protocol (condition × time interaction, P < 0.001). †Different from LH at same time, P < 0.01.

Insulin concentration peaked 30 and 45 min after the preexercise protein drink in LH and HH, respectively (Table 2). Amino acids appeared in the blood at a similar rate. In LH, amino acids reached a plateau and concentrations remained elevated at 75 min postdrink (P < 0.001). In HH, amino acids peaked 30 min postdrink, and then declined, before appearing to reach a steady-state above baseline 90 min postdrink (P < 0.05; Table 2). Note that the values in Table 2 do not reflect the second 18-g protein drink that was given 90 min after arm exercise in each condition.

Table 2.

Plasma insulin and blood amino acid concentrations

| Pretraining | Time, min |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 75 | 90 | ||

| Insulin | |||||||

| HH | 7.9 ± 0.7a | 9.4 ± 0.9ab | 12.5 ± 1.8b | 10.3 ± 1.4ab | 8.2 ± 0.5a | ||

| LH | 8.0 ± 0.6a | 11.4 ± 1.1ab | 15.9 ± 1.8c | 12.6 ± 1.1bc | 8.7 ± 0.7a | ||

| BCAA | |||||||

| HH | 395 ± 13a | 566 ± 26c | 510 ± 21bc | 452 ± 23ab | 487.0 ± 34bc | ||

| LH | 394 ± 17a | 486 ± 24ab | 563 ± 36bc | 618 ± 39c | 608 ± 45c | ||

| EAA | |||||||

| HH | 711 ± 25a | 983 ± 47c | 884 ± 37bc | 798 ± 40ab | 885 ± 61bc | ||

| LH | 728 ± 35a | 851 ± 38ab | 1,009 ± 62bc | 1,114 ± 67c | 1,096 ± 755c | ||

| Total AA | |||||||

| HH | 1,958 ± 66a | 2,611 ± 122c | 2,452 ± 104bc | 2,132 ± 150ab | 2,356 ± 129bc | ||

| LH | 1,966 ± 99a | 2,206 ± 95ab | 2,367 ± 135bc | 2,548 ± 161bc | 2,494 ± 170bc | ||

Values are means ± SE in μM for amino acids (AA) and in μIU/ml for insulin. Blood sample time points in this table are referenced to the protein drink that participants consumed immediately before exercise and therefore do not match the time points in the hormone graphs that are referenced to the end of exercise (e.g., Fig. 1). Because the length of the HH exercise bout was ∼15 min. longer than the LH bout, blood samples are only available for select time points and were analyzed within condition. For amino acids, there was a main effect for time in each condition for branched chain AA (BCAA), essential AA (EAA), and total AA (all P < 0.001) where different superscript letters indicate significantly different means (P < 0.05). For insulin, there was a main effect for time in HH and LH (P < 0.05 and 0.001, respectively) where different superscript letters indicate significantly different means (P < 0.05).

Strength.

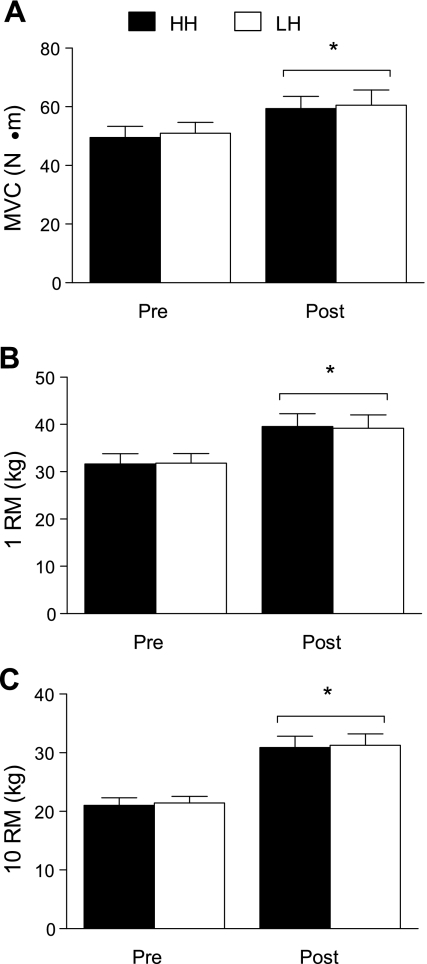

Isometric strength increased 20 ± 4% (range: 3–49%) in LH and 19 ± 3% (range: 2−34%) in HH with training (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A), but there were no differences between conditions (condition × training interaction, P = 0.65). Similarly, 1 RM increased 23 ± 6% (2–56%) in LH and 25 ± 5% (2–53%) in HH (P < 0.001, Fig. 2B) with no effect of condition (P = 0.43). The 10 RM increased 46 ± 3% (33–62%) in LH and 47 ± 6% (20–100%) in HH (P < 0.001, Fig. 2C), but there were no differences between conditions (P = 0.63).

Fig. 2.

Maximal voluntary contraction (MVC; A), one-repetition maximum (1 RM; B), and 10-repetition maximum (10 RM; C) before and after training in LH and HH. *Main effect of training, P < 0.001; there were no interactions (training × condition) for any strength measure (P = 0.65, 0.43, 0.63 for MVC, 1 RM and 10 RM, respectively). Values are means ± SE.

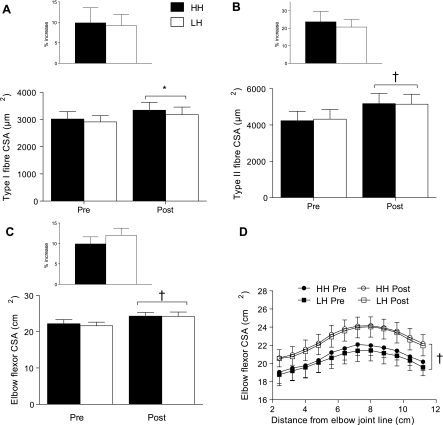

Muscle fiber and elbow flexor CSA.

Type I muscle fiber CSA increased 9 ± 3% (0–16%) in LH and 11 ± 4% (0–26%) in HH with training (P < 0.01, Fig. 3A) while type II muscle fiber CSA increased 21 ± 4% (8–42%) in LH and 24 ± 6% (9–53%) in HH (P < 0.001, Fig. 3B); there were no differences between conditions for either fiber type (condition × training interaction, P ≥ 0.55). Elbow flexor CSA increased 12 ± 2% (3–18%) in LH and 10 ± 2% (4–20%) in HH with training (P < 0.001), with no differences between conditions (condition × training interaction, P = 0.27; Fig. 3C). Figure 3D shows elbow flexor CSA as a function of the distance from the elbow joint line for 12 serial slices for each condition; there were no differences when accounting for the position of the measurement.

Fig. 3.

Type I (A) and II fiber (B) cross-sectional area (CSA) of the biceps brachii before (Pre) and after (Post) training in LH and HH; main effect of training, *P < 0.01, †P < 0.001. Elbow flexor CSA before and after training (C) in LH and HH; main effect of training, †P < 0.001. Elbow flexor CSA as a function of distance from the elbow joint line before and after training (D) in LH and HH; main effect of training, †P < 0.001. There were no interactions (training × condition) for either fiber or whole muscle CSA (type I, P = 66; type II, P = 0.55; CSA, P = 0.27). Values are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we were able to effectively manipulate endogenous hormone concentrations so that, during the acute postexercise time period when amino acids were readily available for protein synthesis, one arm was repeatedly exposed to marked increases in GH, IGF-1, as well as total and free testosterone concentration. The contralateral arm was exposed to only basal levels of these hormones. Despite vast differences in hormone availability in the immediate postexercise period, we found no differences in the increases in strength or hypertrophy in muscle exercised under low or high hormone conditions after 15 wk of resistance training. These findings are in agreement with our hypothesis and previous work showing that exercise-induced hormone elevations do not stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis (36) and are not necessary for hypertrophy (37). Thus our data (36 and present observations), when viewed collectively, lead us to conclude that local mechanisms are of far greater relevance in regulating muscle protein accretion occurring with resistance training and that acute changes in hormones, such as GH, IGF-1, and testosterone, do not predict or in any way reflect a capacity for hypertrophy.

We found no additional strength improvements in the arm trained under the HH condition, which is in contrast to a study (10) that is commonly cited (e.g., 14, 18–20, 30, 31) to support the thesis that exercise-induced increases in hormone availability enhance training adaptations. However, the finding of greater isometric strength gains due to physiological hormone elevations in the previous study (10) may have been related to differences in baseline strength between different groups training with either low or high hormone concentrations. In the present study there was no difference between arms in any of our measures of strength before or after training. Moreover, in agreement with our data, Hansen and co-workers (10) reported no effect of exercise-induced rises in hormone levels on dynamic strength gains with training. Since our study was a within-subject design, we can expect that a portion of the increase in strength was due to cross-education effects, i.e., increased strength in the limb that is contralateral to the training limb, which is ∼7% of initial strength in the elbow flexors (5). Additionally, any contribution to increased strength due to cross-education would have likely benefited both arms similarly and is a reflection of increased motorneuron output rather than muscular adaptations (6).

In addition to measuring changes in strength, we quantified whole muscle and fiber CSA to determine if exercise-induced elevations in circulating hormones enhances muscle hypertrophy with resistance training. We found no effect of elevated hormones on the degree of muscle hypertrophy measured by either MRI or histochemical staining with 15 wk of training. Instead, our data showed virtually identical increases in both muscle fiber and whole muscle CSA regardless of hormonal condition. These findings agree with the notion that local and not systemic factors are responsible for initiating signaling responses in type I and II fibers in response to resistance exercise (34).

By strictly supervising each session of a progressive training program, we successfully maintained divergent hormone profiles in the acute recovery period after exercise. That is, LH and HH elicited low and high hormone (and lactate) responses, respectively, at both the beginning and through to the end of training. The mechanisms that drive increases in exercise-induced hormones, as well as the biological relevance of exercise-induced hormones, are unclear but are more likely related to metabolic stress and/or fuel mobilization rather than muscle anabolism. It is important to note that the transient physiological increase in hormone availability that can occur after resistance exercise is in contrast to the continued marked elevation that is observed with pharmacological administration, which can have an effect on overall muscle mass depending on the hormone. For example, supraphysiological doses of testosterone are clearly potently anabolic to skeletal muscle (3) whereas GH supplementation has little effect on the exercise-induced increase in muscle mass (39). Furthermore, there is evidence that a minimal basal level of testosterone is required to support strength and hypertrophy gains, which are otherwise attenuated (20). Therefore, the hormone-sensitive processes that underpin muscle anabolism at hypo- and supraphysiological hormone levels are not being activated appreciably by exercise-induced increases in hormone availability or at least do not result in any measurable enhancement of strength or hypertrophy.

In our view, resistance exercise provides an intrinsic stimulus to the working muscle, which drives hypertrophy, and whereas physiological systemic hormone concentrations may be permissive for the hypertrophic process, exercise-induced elevations do not enhance or in any way predict hypertrophy. Resistance exercise results in the phosphorylation of critically important signaling pathway proteins that are correlated with the extent of muscle hypertrophy in rodents (2) as well as humans (35). These data (2, 35) suggest that local mechanisms within the muscle are of paramount importance in determining muscle hypertrophy. Clearly further research is required to clarify how these mechanisms, possibly in concert with local growth factors (1), combine with other mechanical signals to stimulate muscle protein synthesis and facilitate muscle protein accretion. Ultimately, muscle hypertrophy is specific to the trained muscle group, and strength adaptations are specific to the characteristics of the training regime (29); our data suggest that these adaptations are dissociated from acute exercise-induced hormonal rises.

In summary, transient resistance exercise-induced increases in endogenous purportedly anabolic hormones do not enhance muscle strength or hypertrophy following 15 wk of resistance training. Instead, our data are consistent with the notion that local mechanisms are of primary relevance in producing gains in muscle strength and hypertrophy with resistance training. These findings, combined with our previous work (36, 37), provide multiple lines of evidence that exercise-induced elevations of purportedly anabolic hormones are not necessary for, and do not enhance, muscle anabolism in young men. Our data indicate that exercise-induced changes in concentrations of systemic hormones do not reflect the underlying processes of muscle protein accretion and cannot be used as a proxy marker of muscle hypertrophy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada grant to S. M. Phillips. D. W. D. West, J. E. Tang, A. W. Staples, and D. R. Moore are Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canada Graduate Scholarship Award recipients, and all authors acknowledge those sources of support during the conduct of this research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Todd Prior and Tracy Rerecich for technical assistance and our participants for their time and effort. We are grateful to Gianni Parise and Warren Foster for use of equipment for muscle fiber analysis and to Dean Inglis and Jonathan Adachi for assistance with MRI.

We thank Protient for the generous donation of whey protein isolate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams GR. Autocrine/paracrine IGF-I and skeletal muscle adaptation. J Appl Physiol 93: 1159–1167, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baar K, Esser K. Phosphorylation of p70(S6k) correlates with increased skeletal muscle mass following resistance exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C120–C127, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, Callegari C, Clevenger B, Phillips J, Bunnell TJ, Tricker R, Shirazi A, Casaburi R. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. N Engl J Med 335: 1–7, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buresh R, Berg K, French J. The effect of resistive exercise rest interval on hormonal response, strength, and hypertrophy with training. J Strength Cond Res 23: 62–71, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carroll TJ, Herbert RD, Munn J, Lee M, Gandevia SC. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: evidence and possible mechanisms. J Appl Physiol 101: 1514–1522, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carroll TJ, Herbert RD, Munn J, Lee M, Gandevia SC. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: evidence and possible mechanisms. J Appl Physiol 101: 1514–1522, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol 37: 247–248, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gotshalk LA, Loebel CC, Nindl BC, Putukian M, Sebastianelli WJ, Newton RU, Hakkinen K, Kraemer WJ. Hormonal responses of multiset versus single-set heavy-resistance exercise protocols. Can J Appl Physiol 22: 244–255, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hakkinen K, Pakarinen A. Acute hormonal responses to two different fatiguing heavy-resistance protocols in male athletes. J Appl Physiol 74: 882–887, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen S, Kvorning T, Kjaer M, Sjogaard G. The effect of short-term strength training on human skeletal muscle: the importance of physiologically elevated hormone levels. Scand J Med Sci Sports 11: 347–354, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hartman JW, Tang JE, Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, Lawrence RL, Fullerton AV, Phillips SM. Consumption of fat-free fluid milk after resistance exercise promotes greater lean mass accretion than does consumption of soy or carbohydrate in young, novice, male weightlifters. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 373–381, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hubal MJ, Gordish-Dressman H, Thompson PD, Price TB, Hoffman EP, Angelopoulos TJ, Gordon PM, Moyna NM, Pescatello LS, Visich PS, Zoeller RF, Seip RL, Clarkson PM. Variability in muscle size and strength gain after unilateral resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37: 964–972, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim PL, Staron RS, Phillips SM. Fasted-state skeletal muscle protein synthesis after resistance exercise is altered with training. J Physiol 568: 283–290, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kraemer WJ. Endocrine responses to resistance exercise. In: Essentials of Strength and Conditioning , edited by Baechle TR, Earle RW. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000, p. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, Dudley GA, Dooly C, Feigenbaum MS, Fleck SJ, Franklin B, Fry AC, Hoffman JR, Newton RU, Potteiger J, Stone MH, Ratamess NA, Triplett-McBride T. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34: 364–380, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kraemer WJ, Fry AC, Warren BJ, Stone MH, Fleck SJ, Kearney JT, Conroy BP, Maresh CM, Weseman CA, Triplett NT. Acute hormonal responses in elite junior weightlifters. Int J Sports Med 13: 103–109, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kraemer WJ, Marchitelli L, Gordon SE, Harman E, Dziados JE, Mello R, Frykman P, McCurry D, Fleck SJ. Hormonal and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercise protocols. J Appl Physiol 69: 1442–1450, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kraemer WJ, Nindl BC, Marx JO, Gotshalk LA, Bush JA, Welsch JR, Volek JS, Spiering BA, Maresh CM, Mastro AM, Hymer WC. Chronic resistance training in women potentiates growth hormone in vivo bioactivity: characterization of molecular mass variants. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E1177–E1187, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Med 35: 339–361, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kvorning T, Andersen M, Brixen K, Madsen K. Suppression of endogenous testosterone production attenuates the response to strength training: a randomized, placebo-controlled, and blinded intervention study. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E1325–E1332, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ly LP, Handelsman DJ. Empirical estimation of free testosterone from testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin immunoassays. Eur J Endocrinol 152: 471–478, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacDougall JD, Gibala MJ, Tarnopolsky MA, Macdonald JR, Interisano SA, Yarasheski KE. The time course for elevated muscle protein synthesis following heavy resistance exercise. Can J Appl Physiol 20: 480–486, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mauras N. Growth hormone and sex steroids. Interactions in puberty. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 30: 529–544, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCall GE, Byrnes WC, Fleck SJ, Dickinson A, Kraemer WJ. Acute and chronic hormonal responses to resistance training designed to promote muscle hypertrophy. Can J Appl Physiol 24: 96–107, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore DR, Tang JE, Burd NA, Rerecich T, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Differential stimulation of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein synthesis with protein ingestion at rest and after resistance exercise. J Physiol 587: 897–904, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phillips SM, Tipton KD, Aarsland A, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR. Mixed muscle protein synthesis and breakdown after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 273: E99–E107, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch TK, Housch TJ, Kibler WB, Kraemer WJ, Triplett NT. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41: 687–708, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ratamess NA, Kraemer WJ, Volek JS, Maresh CM, Vanheest JL, Sharman MJ, Rubin MR, French DN, Vescovi JD, Silvestre R, Hatfield DL, Fleck SJ, Deschenes MR. Androgen receptor content following heavy resistance exercise in men. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 93: 35–42, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sale DG. Neural adaptation to resistance training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 20: S135–S145, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spiering BA, Kraemer WJ, Anderson JM, Armstrong LE, Nindl BC, Volek JS, Maresh CM. Resistance exercise biology: manipulation of resistance exercise programme variables determines the responses of cellular and molecular signalling pathways. Sports Med 38: 527–540, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spiering BA, Kraemer WJ, Vingren JL, Ratamess NA, Anderson JM, Armstrong LE, Nindl BC, Volek JS, Hakkinen K, Maresh CM. Elevated endogenous testosterone concentrations potentiate muscle androgen receptor responses to resistance exercise. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 114: 195–199, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stewart BG, Tarnopolsky MA, Hicks AL, McCartney N, Mahoney DJ, Staron RS, Phillips SM. Treadmill training-induced adaptations in muscle phenotype in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve 30: 61–68, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang JE, Manolakos JJ, Kujbida GW, Lysecki PJ, Moore DR, Phillips SM. Minimal whey protein with carbohydrate stimulates muscle protein synthesis following resistance exercise in trained young men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 32: 1132–1138, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tannerstedt J, Apro W, Blomstrand E. Maximal lengthening contractions induce different signaling responses in the type I and type II fibers of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 106: 1412–1418, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Terzis G, Georgiadis G, Stratakos G, Vogiatzis I, Kavouras S, Manta P, Mascher H, Blomstrand E. Resistance exercise-induced increase in muscle mass correlates with p70S6 kinase phosphorylation in human subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 102: 145–152, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. West DW, Kujbida GW, Moore D, Atherton PJ, Burd NA, Padzik JP, Delisio M, Tang JE, Parise G, Rennie MJ, Baker SK, Phillips SM. Resistance exercise-induced increases in putative anabolic hormones do not enhance muscle protein synthesis or intracellular signalling in young men. J Physiol 587: 5239–5247, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, Grant EJ, Correia CE, Phillips SM. Hypertrophy with unilateral resistance exercise occurs without increases in endogenous anabolic hormone concentration. Eur J Appl Physiol 98: 546–555, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, Macdonald MJ, Macdonald JR, Armstrong D, Phillips SM. Consumption of fluid skim milk promotes greater muscle protein accretion after resistance exercise than does consumption of an isonitrogenous and isoenergetic soy-protein beverage. Am J Clin Nutr 85: 1031–1040, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yarasheski KE, Campbell JA, Smith K, Rennie MJ, Holloszy JO, Bier DM. Effect of growth hormone and resistance exercise on muscle growth in young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 262: E261–E267, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]