Abstract

Mallory-Denk bodies (MDBs) are found in the liver of patients with alcoholic and chronic nonalcoholic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Diethyl 1,4-dihydro-2,4,6,-trimethyl-3,5-pyridinedicarboxylate (DDC) is used as a model to induce the formation of MDBs in mouse liver. Previous studies in this laboratory showed that DDC induced epigenetic modifications in DNA and histones. The combination of these modifications changes the phenotype of the MDB forming hepatocytes, as indicated by the marker FAT10. These epigenetic modifications are partially prevented by adding to the diet S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) or betaine, both methyl donors. The expression of three imprinted ncRNA genes was found to change in MDB forming hepatocytes, which is the subject of this report. NcRNA expression was quantitated by Real-Time PCR and RNA FISH in liver sections. Microarray analysis showed that the expression of three ncRNAs was regulated by DDC: up regulation of H19, antisense Igf2r (AIR), and down regulation of GTL2 (also called MEG3). S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) feeding prevented these changes. Betaine, another methyl group donor, prevented only H19 and AIR up regulation induced by DDC, on microarrays. The results of the SAMe and betaine groups were confirmed by Real-Time PCR, except for AIR expression. After 1 month of drug withdrawal, the expression of the three ncRNAs tended toward control levels of expression. Liver tumors that developed also showed up regulation of H19 and AIR. The RNA FISH approach showed that the MDB forming cells’ phenotype changed the level of expression of AIR, H19 and GTL2, compared to the surrounding cells. Furthermore, over expression of H19 and AIR was demonstrated in tumors formed in mice withdrawn for 9 months. The disregulation of ncRNA in MDB forming liver cells has been observed for the first time in drug primed mice associated with liver preneoplastic foci and tumors.

Keywords: MDB: Mallory-Denk Bodies, SAMe: S-Adenosylmethionine, Non-coding RNA: ncRNA, RNA messenger: mRNA, antisense Igf2r: AIR

INTRODUCTION

Mice fed diethyl-1,4-dihydro-2,4,6-trimethyl-3,5-pyridine decarboxylate (DDC) added to a normal mouse diet for 10 weeks, form Mallory-Denk bodies (MDBs) in clusters of hepatocytes (Zatloukal et al., 2007). The MDBs mostly disappear by 1 month of DDC withdrawal (DDC primed hepatocytes). Following 7 days of DDC refeeding MDBs are again formed by scattered groups of hepatocytes (Yuan et al., 1996).

MDBs are found in many liver diseases (Nakanuma and Ohta, 1985; Zatloukal et al., 2007). MDBs are aggresomes of proteins containing p62, cytokeratin (CK8 and 18), Ubb+1 and ubiquitin (Ub) (Zatloukal et al., 2007). However, recent publications showed that DDC induced epigenetic modifications in the liver such as hypomethylation and hyperacetylation of histones were associated with Fat 10 over expression in cells that also formed MDBs (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008a). These changes were prevented by SAMe. These epigenetic modifications induced liver cells to switch their phenotype to form MDBs. Noncoding RNA (ncRNA) expression is regulated by histone modifications and the recruitment of transcription factors on the gene promoters (Barsyte-Lovejoy et al., 2006; Kulshreshtha et al., 2007). NcRNA-mediated gene regulation has its origins in the earliest days of molecular biology, when it was first proposed that sequence-specific ncRNA might interact with promoters to regulate gene expression (Britten and Davidson, 1969; Jacob and Monod, 1961). Forty years later, the understanding of gene regulation, chromosome organization, and epigenetic mechanisms has undergone somewhat of a revolution with the discovery of interference RNA (RNAi). It is now becoming evident that the variety of ncRNA molecules plays an important role in many cellular processes. They are not just mere intermediates in the transfer of genetic information from DNA to proteins. Recent studies have highlighted the role of ncRNAs in a large variety of diseases (Abu-Amero et al., 2008; Benetatos et al., 2008; Cerchia and De Franciscis, 2006; Davis et al., 2004; Reeve, 1996; Sidhu et al., 2003; Szymanski et al., 2005) and have suggested that this class of genes might be used as biomarkers in cancer (Lin et al., 2007; Panzitt et al., 2007). Antisense ncRNAs are often produced from imprinted genes and their expression is usually tissue-specific or limited to certain stages of development (Pauler et al., 2007; Royo et al., 2006).

The three ncRNAs studied here were GTL2, AIR and H19 and were identified by microarray analysis performed on livers where MDBs had formed (Oliva et al., 2008b).GTL2 (also called MEG3) is a ncRNA imprinted gene located within a one Mb imprinted domain on murine distal chromosome 12 (Kato et al., 2007). It functions as a tumor suppressor (Zhao et al., 2005). An intergenic differentially methylated region (DMR) (Hiura et al., 2007) controls the expression of GTL2. The disregulation of the GLT2-DLK1 cluster is linked to tumorgenesis (Astuti et al., 2005; Declercq et al., 2005; Fukuzawa et al., 2005; Kawakami et al., 2006; Yin et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2005). GTL2 is down regulated in Wilm’s tumor, pituitary tumors and up regulated salivary gland tumors (Astuti et al., 2005; Declercq et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005). This GTL2-DLK1 cluster is rich in imprinted miRNAs (Williams et al., 2007) and their expression also could be linked with tumor formation (Saito et al., 2006). Some of the miRNAs are also linked with tumorgenesis e.g: mir-127 (Saito et al., 2006) and mir-136 (Yu et al., 2006). Antisense Igf2r ncRNA (AIR), a polyadenylated transcript, regulates genomic imprinting of a cluster of autosomal genes on mouse chromosome 17, in the imprinted Igf2R cluster (Braidotti et al., 2004). Targeted manipulations in mice have shown that the expression of 108 kb long AIR ncRNA exerts a silencing effect in cis on three protein-coding genes Igf2r, Slc22a2 and Slc22a3, spread over 300 kb (Sleutels et al., 2002). It is not known if the silencing of AIR ncRNA is through RNA itself or at the localization of its promoter in the second intron of IGF2R (Sleutels et al., 2002). H19 is a ncRNA, 2.3Kb, which is maternally expressed (it belongs to an imprinted cluster) (Gabory et al., 2006), and controls the expression of IGF2 (paternally expressed). H19 is over expressed during embryogenesis, and shut off in most tissues after birth. H19 plays a role in tumorgenesis as an inducer of tumors and is up regulated in different types of cells (Matouk et al., 2007). It is essential for human tumor growth (Matouk et al., 2007).

Microarray analysis showed that the expression of H19 and AIR were increased by DDC refeeding and GTL2 was decreased by DDC refeeding. These changes are partially prevented by SAMe feeding (Oliva et al., 2008b). Betaine, another methyl donor, partially prevented the H19 and AIR expression induced by DDC refeeding (Oliva et al., 2008b). Real-Time PCR confirmed these results. Previous studies in which DDC was fed and withdrawn for 8 to 15 months (drug primed mouse model) led to the formation of preneoplastic liver cell foci and tumors in the liver (Nan et al., 2006a; Oliva et al., 2008a; Roomi et al., 2006). Besides the up regulation of tumor markers (AFP, GSTmu2, FAT10) (Nan et al., 2006a; Oliva et al., 2008a; Roomi et al., 2006), the disregulation of the expression of these three ncRNAs possibly participated in the formation of the tumors. By RNA-FISH, the cellular expression of these AIR and H19 ncRNAs was changed after DDC refeeding. H19 and AIR were down regulated in the cells forming MDBs, compared with the surrounding cells, and up regulated in the liver tumors, which formed. Real-Time PCR on liver tumors showed an increased expression of AIR and H19 ncRNA. H19 is over expressed in human tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma such as the HepG2 cell line, (Sohda et al., 1998) which has been confirmed by us (unpublished results). GTL2 is down regulated in different tumors (Astuti et al., 2005; Fukuzawa et al., 2005; Kawakami et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2005). The purpose of the present study is to document the disregulation of ncRNAs induced by DDC, which is associated with MDB and tumor formation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

One-month-old C3H male mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, San Diego, CA) were fed DDC (0.1% diethyl 1,4-dihydro-2, 4, 6-trimethyl-3, 5-pyridinedicarboxylate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 10 weeks to induce MDB formation in vivo. They were then withdrawn from the drug for 1 month (n=4). These mice were then refed DDC with or without S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), 4g/kg body wt/day by gavage (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 7 days, or with and without betaine (2% in the drinking water) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The tumors formed after 9 months of drug withdrawal. All mice were treated in a humane manner as approved by the Animal Care Committee at Harbor-UCLA Laboratory BioMedical Research Institute according to the Guidelines of the National Academy of Science. RNA was extracted from some livers for microarrays and Quantitative RT-PCR. Portions of each liver were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. In addition, samples from each liver were fixed in 10% zinc buffered formalin for 4 hours and then stored in 80% alcohol. They were embedded in paraffin for light and immunofluorescent microscopy.

Immunofluorescent staining

The cover slips and liver biopsy sections were stained with rabbit anti-ubiquitin polyclonal antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Binding of the antibody was detected with Texas-Red labeled and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson, West Grove, PA). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. The slides were examined using a Nikon-400 fluorescent microscope with a triple color band cube to detect simultaneously FITC, Texas Red and DAPI staining. Confocal microscopy was perfomed using a Keika fluorescent microscope.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay

Total liver RNAs were extracted with Trizol Plus RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Synthesis of cDNAs was performed with 5 μg total RNA, and 50 ng random hexamer primers using SuperSriptIII RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR primers were designed with the assistance of the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primers used for H19, AIR, GTL2, AFP and Gankyrin were:

| H19 | NR_001592 | Forward | AATGGTGCTACCCAGCTCAT |

| NR_001592 | Reverse | TCAGAACGAGACGGACTTAAAGAA | |

| AIR | NR_002853 | Forward | TGAGACAGGTGAAACGTCTGATG |

| NR_002853 | Reverse | GGTGTGGTGGTGTAAGTCTGTAATCT | |

| GTL2 | NR_003633 | Forward | GGACTTCACGCACAACACGTT |

| NR_003633 | Reverse | GTCCCACGCAGGATTCCA | |

| AFP | NM_007423 | Forward | ACGAAAATGAGTTTGGGATAGCTT |

| NM_007423 | Reverse | GCATAGCTACCATCACCTTTACCC | |

| Gankyrin | NM_016883 | Forward | GCTGGCCATACAGAAATTGTTGA |

| NM_016883 | Reverse | ACCAACCTGCGTCATCTTTATCA |

Sense and anti-sense: Quantitative PCR was achieved by using the SYBR Green JumpStart™ Tag ReadyMix (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The thermal cycling consists of an initial step at 50°C for 2 min, followed by a denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Single PCR product was confirmed with the heat dissociation protocol at the end of the PCR cycles. Quantitative values were obtained from the threshold PCR cycle number (Ct) at which point the increase in signal associated with an exponential growth for PCR product starts to be detected. The target mRNA abundance in each sample was normalized to its 18S level as ΔCt = Cttarget gene – Ct18S. For each target gene, the highest ΔCt was assigned as ΔCtmax.

Amplification and cloning of H19 and AIR probes

The probes for AIR and H19 were amplified by using the Taq Platinum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The conditions of the PCR are: 94°C 5mn, 94°C 1mn, 57°C 1mn, 72°C 1mn (40 cycles), 72°C 5mn. The PCR product is separated in 1% Agarose gel using the NucleoSpin Extract II (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA). The purified PCR products are cloned in the pGMET vectors, overnight at 16°C, following the instructions of the company (Promega, Madison, WI). JM109 bacteria are transformed with the ligation product (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Positive clones are selected with EcoRI digestion. All the clones are sequenced. Sequence of the primers used to amplify the probe:

Hybridization in situ of RNA (RNA FISH)

The slides were placed for 10mn in Xylene, 10mn in 1:1 Xylene/EtOH and finally 10mn in 100% EtOH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). They are washed in PBS and placed in digestion buffer (PBS+SDS 0.05%+Proteinase K 10μg/ml) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), at room temperaturefor 10 mn. They are then fixed in cold fresh-made 4% paraformaldehyde, at 4°C, 10 mn. They are washed in PBS and placed in 0.1M PBS/Tween20 0.1%, for 30 mn. They are then placed in the prehybridization buffer (1:1 Formamide/5 xSSC) for 2h at 65°C. The probe is made using a Fluorescein High-Prime, following the instruction of the company (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The probe is incubated with the slides at 65°C, 16h. The slides are washed in 2X SSC, for 30mn at RT, 1h at 65°C in 2X SSC, 1 h at 65°C with 0.2X SSC, 10mn at PBS/Tween20 65°C and 10mn with PBS/Tween20 at room temperature.

Microarray data

Previous microarray data published (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008b; Oliva et al., 2008c) were analysed to look for the presence of ncRNA values.

Statistical Analysis and Microarray Analysis

P values were determined by ANOVA and student-Newman-Keuls for multiple group comparisons (Sigma-Stat software, San Francisco, CA). Microarrays were analyzed using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test comparison analysis to derive biologically significant results from the raw probe cell intensities on expression arrays. For comparison analysis, each probe set on the experiment array was compared with its counterpart on the control array to calculate the change in P value that was used to generate the difference call of increase (I; P<0.04), marginal increase (MI; P<0.04 to P<0.06), decrease (D; P>0.997), marginal decrease (MD; P>0.992 to P>0.997), or no change (NC: P>0.06 to P<0.997). Comparison analysis was used to generate a signal log ratio for each probe prior to the experimental array to the corresponding probe pair on the control array. This strategy cancels out differences resulting from different probe finding coefficients. Signal log ratio was computed by using a one-step Tukey’s biweight method by taking a mean of the log ratio of probe pair intensities across the two arrays.

Results

Two independent microarray analyses showed a variation in the expression of a few ncRNAs in the mouse liver primed by DDC refeeding (Li et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008b; Oliva et al., 2008c). In the first experiment, using SAMe as a methyl donor, the expression of seven ncRNAs on 1667 genes was changed by DDC refeeding. In the second experiment, with betaine as the methyl donor, the expression of only four ncRNAs of 5050 genes was changed by DDC refeeding. Among them, three were in common and interesting: H19, AIR and GTL2 (Table 1). The microarray analysis showed an increase in the expression of H19 and AIR by DDC, and this was prevented by SAMe and betaine. Their expression almost recovered after one month of drug withdrawal (Table 1). GTL2 was down regulated by DDC and this was not prevented by SAMe and betaine. However, the expression of GTL2 partially recovered after one month of drug withdrawal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variation in the expression of ncRNA, in microarray analysis. Two independent experiments. (ND : No difference) N=3

| DDC Refed vs Contro | DDC Refed+SAMe vs DDC | 1Wd vs C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | 11.88 | −6.06 | ND |

| Air | 2.07 | −2.89 | ND |

| GTL2 | −8.88 | 5.28 | −2.27 |

| IGF2as | −6.36 | ND | ND |

| Snora65 | 2.19 | ND | 1.93 |

| Snhg3 | 3.36 | 1.93 | 2.6 |

| Snord22 | 1.7 | ND | 1.7 |

| DDC Refed vs Control | DDC Refed+Betaine vs DDC | 1Wd vs C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | 54.19 | −9 | ND |

| Air | 7.84 | −3.78 | ND |

| GTL2 | −5.31 | ND | −2.17 |

| Snhg8 | −2.5 | ND | ND |

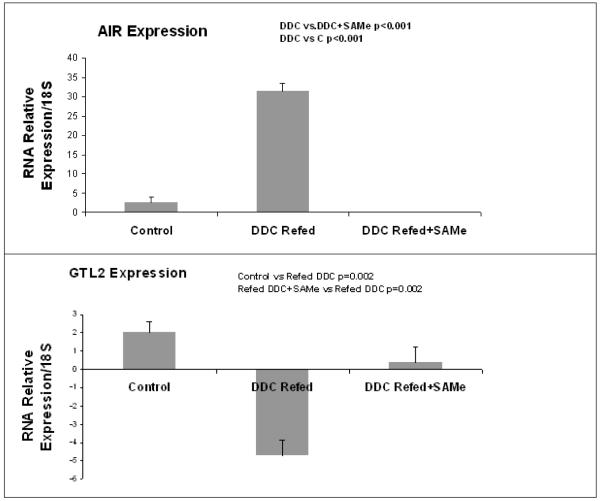

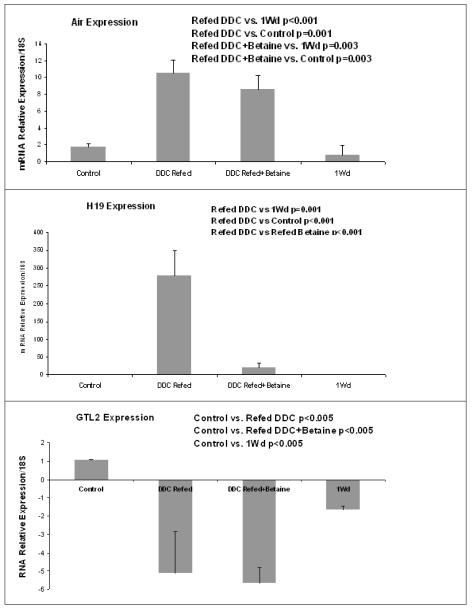

Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the results of microarrays. DDC induced the expression of H19 (60 and 30 times respectively for the SAMe group) and AIR ncRNA (10 and 250 in the betaine group).The expression of GTL2 was reduced (5 times in the SAMe and betaine group). SAMe prevented the DDC disregulation of the three ncRNAs (Fig 1). Betaine prevented the disregulation of H19 induced by DDC but not for the two other genes (Fig 2).

Figure 1.

Real-Time PCR analysis of the expression of H19, AIR and GTL2 ncRNA. Refeeding DDC induced the expression of H19 and AIR. This was completely prevented by SAMe. The ncRNA of H19 and AIR were undetectable in the DDC+SAMe treatment group. In contrast, refeeding DDC decreased the expression of GTL2 and this was prevented by SAMe. (Mean ±, SEM, N=3)

Figure 2.

Real-Time PCR analysis of the expression of H19, AIR and GTL2 ncRNA. Refeeding DDC induced the expression of H19 and AIR, which was partially or completely prevented by betaine treatment. In contrast, refeeding DDC decreased the expression of GTL2.This was partially prevented by SAMe treatment. (Mean ±, SEM, N=3)

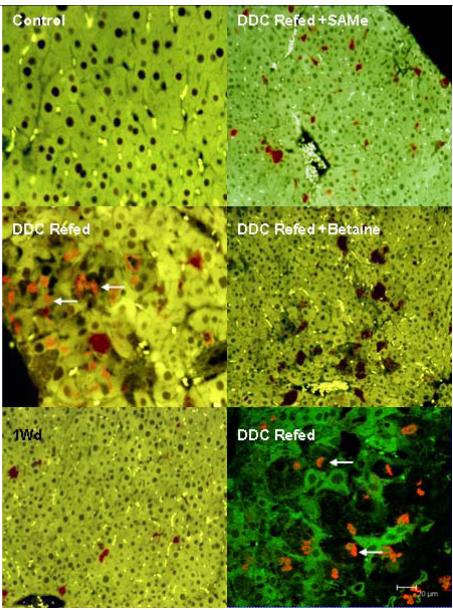

By RNA-FISH, AIR expression was homogenous in the control liver as well as for refed DDC+SAMe (Fig 3). However, with DDC refeeding, this expression was heterogeneous in the liver. AIR expression was decreased in the cells forming MDBs, compare to the surrounding cells (Fig 3). SAMe and one month drug withdrawal (Fig 3) restored completely the expression of AIR ncRNA and the formation of MDBs. As expected, betaine partially prevented the formation of MDBs and restored partially the expression of AIR ncRNA. The confocal microscopy showed clearly the formation of MDBs in cells expressing less AIR RNA. The same results were found with H19 (Fig 4). GTL2 was decreased in MDB positive cells after refeeding DDC. However SAMe and betaine failed to prevent this change (data not shown), which did not correlate with the PCR and microarray data.

Figure 3.

RNA FISH on AIR ncRNA: Control x40; DDC Refed x40; 1 month withdrawal x20; DDC Refed +SAMe x20; DDC Refed +Betaine x20; DDC Refed Confocal picture. The expression of AIR is changed in the liver of a mouse, refed with DDC. SAMe prevented MDBs formation and the disregulation of AIR expression. In the confocal merged photo, cells forming MDBs express less AIR RNA. White arrows indicate MDB stained red with ubiquitin antibody and Texas Red.

Figure 4.

RNA FISH for H19 ncRNA. Control x20; DDC Refed x20; 1 month withdrawal x20; DDC Refed +SAMe x20; DDC Refed +Betaine x20; DDC Refed Confocal picture. The expression of H19 is changed in mouse liver refed DDC. SAMe prevents MDB formation and the disregulation of H19 expression. In the confocal picture, cells forming MDBs express less H19 RNA. White arrows indicate MDB which stained red with ubiquitin antibody and Texas Red.

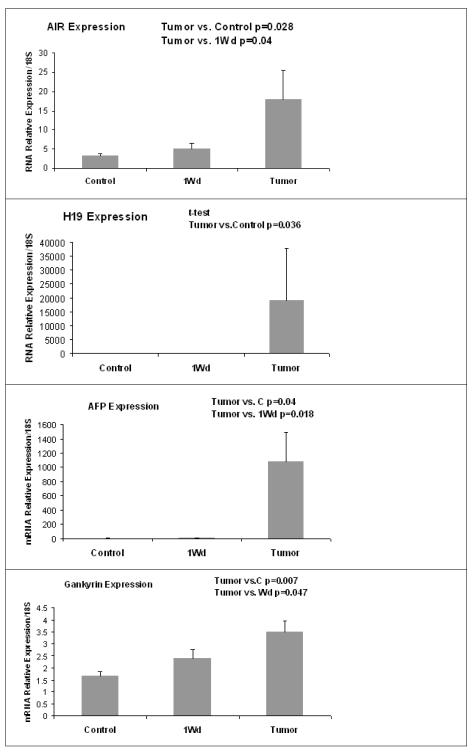

In addition, Real-Time PCR was done on RNA extracted from tumors formed after 9 months of drug withdrawal (Fig 5). H19 and AIR had a low level of expression in the control and 9 months withdrawal liver, but an increase in their expression was observed in liver tumors (Fig 5). AFP and Gankyrin expression, two HCC markers, were increased in the tumors (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis by Real-Time PCR, the expression of H19 and AIR ncRNA in liver tumors. AFP and Gankyrin, 2 tumors markers were analysed too. ncRNA expression of H19 and AIR was increased in the liver tumoral as like the tumors markers AFP and Gankyrin. (Mean ±, SEM, N=6,3,3)

DISCUSSION

MDB formation is associated with ALD, NASH, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2005; French, 2000; Nakanuma and Ohta, 1985; Riley et al., 2002; Zatloukal et al., 2007). MDB formation is also associated with progressive liver injury and higher mortality rates in alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhotic patients (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2005; Chedid et al., 1991; Orrego et al., 1983; Zatloukal et al., 2007). Thus, MDB formation is an important component of liver disease. MDBs are composed of keratins, chaperones, and proteins from proteasome degradation such as ubiquitin, p62 and Ubb+1 (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2004; Cadrin et al., 1992; McPhaul et al., 2002). This formation is controlled by phosphoproteins (Nan et al., 2006b). A factor that is common to all these proteins is that mRNA codes them. To date there have been no publications which have referred to a variation of ncRNA expression induced by DDC and the ncRNAs possible link to MDB formation.

In previous studies, DDC induced epigenetic modification of DNA and histones in the liver such as hypotrimethylation of H3K4 and H3K9, hyperacetylation of H3K9 and hypomethylation of DNA in cells forming MDBs (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008a). The acetylation of H3K9 impedes the methylation of the same residue, which can impede or disturb the methylation of DNA (Jackson et al., 2002; Soppe et al., 2002; Tariq et al., 2003). A global acetylation of H3K9 and a decrease of trimethylation of H3K9 lead to a global increase of gene expression. Trimethylation of H3K9 and deacetylation leads to gene silencing, because H3K9me3 acts as a binding site for the heterochromatin-forming protein HP1 (Lachner et al., 2001). In the drug-primed mouse model, H3K9me3 is decreased and H3K9 acetylation is increased when the drug is refed and a large number of changes in gene expression are observed (Li et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008a). DNA methylation is dependent on prior histone methylation (Fuks et al., 2003a; Fuks et al., 2003b; Jackson et al., 2002; Tamaru and Selker, 2001). Histone alterations can influence long-term effects on gene expression patterns by influencing chromatin structure throughout the cell cycle and from one cell generation to the next (Ringrose and Paro, 2004).

The changes in expression levels and epigenetic alterations affecting the ncRNAs, which accompany malignant processes, strongly support the functional role of ncRNAs. DNA hypomethylation, as a consequence of imprinting, can disregulate the expression of genes controlled by DNA imprinting. Among these genes, DNA imprinting controls the expression of ncRNA (Royo et al., 2006). Interestingly, hypomethylation of DNA was only observed in cells forming MDBs, not in the surrounding normal cells (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008a). This, however, cannot explain global up regulation of AIR and H19 induced by DDC refeeding and the down regulation of GTL2. Only global DNA methylation changes could explain the disregulation of the expression of these 3 ncRNAs (Astuti et al., 2005; Haruta et al., 2008; Honda et al., 2008; Ward and Dutton, 1998). The change in the DNA methylation pattern affects the expression of imprinted genes, among them the three ncRNA studied here, ie.: H19, AIR and GTL2. Since the discovery of ncRNAs (Lee et al., 1993), it has been shown that they are involved in gene silencing, transcription, RNA splicing, editing, translation, DNA imprinting, DNA demethylation, chromatin structure dynamics, RNA interface and cancers (Bartel, 2004; Mattick and Makunin, 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). The expression of ncRNA is controlled by DNA methylation, histone modifications (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Vu et al., 2004) and transcription factors (Seidl et al., 2006).

Real-Time PCR indicated a global increase of the expression of AIR and H19 in liver. The expression of GTL2 was decreased. As showed in previous studies, the disregulation of gene expression, epigenetic modifications and MDB formation induced by DDC are all prevented by SAMe feeding (Bardag-Gorce et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Oliva et al., 2008a). The same result occurs with these three ncRNAs when SAMe treatment is given. However, betaine, causing fewer effects, didn’t prevent AIR and GTL2 disregulation. DDC refeeding induced the formation of MDBs, in FAT10 positive cells (Oliva et al., 2008a). However, the cell specific expression of these ncRNAs is unknown. By the RNA-FISH approach, the cell specific expression of H19 and AIR was analyzed. The expression of these two ncRNAs was decreased in cells forming MDBs. This was in contradiction with the Real-Time PCR results (Fig 1 and 2). However, the RNA-FISH technique made it possible to observe the expression of the ncRNAs in individual liver cells. A decrease of ncRNA expression was observed in MDB forming cells and an increase in their expression was seen in the surrounding normal liver cells.

Epigenetic modifications of the genome increased chromosomal instability and later, led to the formation of tumors (Suijkerbuijk and Kops, 2008). Hypermethylation of the promoter of tumor suppressor genes (Paluszczak and Baer-Dubowska, 2006), hypomethylation of oncogenes (Wilson et al., 2007) and a global hypomethylation of DNA (Esteller, 2006; Feinberg et al., 2002; Fraga and Esteller, 2005; Gaudet et al., 2003; Paluszczak and Baer-Dubowska, 2006) are usually observed in tumors. Hypomethylation of DNA was also observed in cells forming MDBs (Oliva et al., 2008a). The hypomethylation observed in these cells could be the first step leading to the formation of tumors (preneoplastic change) (Oliva et al., 2008a). The cells forming MDBs also over express FAT10 protein (Oliva et al., 2008a). The increase of PCNA in positive nuclei in FAT10 positive cells indicates that FAT10 positive cells have a growth advantage similar to tumor cells (Qin and Tang, 2002; Roomi et al., 2006). FAT10 over expression reduces the cell cycle time (Ren et al., 2006). DDC induced the formation of tumors, after 8-15 months withdrawal from DDC (Nan et al., 2006a; Oliva et al., 2008a). DDC induced the expression of tumor markers such as AFP, FAT10 and GSTmu2, and continued to over express FAT10 proteins after months of withdrawal (Nan et al., 2006a; Oliva et al., 2008a). In the tumors formed after nine months of withdrawal, there was an increase of two hepatocellular carcinoma markers. They were AFP and Gankyrin. FAT10 mRNA was still over expressed in these tumors (data not shown). The tumors that formed have the phenotype of HCC (Debruyne and Delanghe, 2008; Fu et al., 2002). Furthermore, the disregulation of the expression of H19, GTL2 and AIR (possibly the result of a change of the imprinting pattern) could initiate tumor formation, especially the antisense RNAs (Lavorgna et al., 2004). However, it could be difficult to analyze the pattern of the DNA methylation in these specifics cells, in vivo. There are many clinical examples studied where disregulation of ncRNA expression and disease processes were found together (Eddy, 2001; McManus, 2003; Szymanski et al., 2005). For instance, H19 is induced by DDC refeeding and H19 acts as an oncogene, promoting tumorgenesis (Matouk et al., 2007). Curcumin, used to block the proliferation of tumor cells by an unknown mechanism (Anand et al., 2008), decreases the expression of H19 transcripts in human tumor cell lines (Novak Kujundzic et al., 2008).

By the RNA-FISH approach, H19 expression was reduced in the cells forming MDBs. The locus DLK1/GTL2 is linked to human tumorgenesis. The hypermethylation of the differentially methylated regions (DMR) of the GTL2 gene is associated with a decrease in the expression of GTL2 that may contribute to the formation of tumors (Astuti et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005). Indeed, GTL2 expression is also down regulated in renal tumors (Astuti et al., 2005; Kawakami et al., 2006), but up regulated in salivary gland tumors (Declercq et al., 2005). No data are available for AIR expression and HCC because human AIR ncRNA was only identified recently (Yotova et al., 2008).

From the point of view of tumor prevention, SAMe as a methyl donor could be effective by methylating histones to silence genes activated by hypomethylation. It will be interesting to see whether or not SAMe feeding during drug withdrawal will decrease the frequency and the number of tumors and will decrease their size. In reference to the changes in ncRNA expression observed in liver tumors reported here, ncRNAs are used to determine metastasis profiling signatures (Barbarotto and Calin, 2008; Barbarotto et al., 2008).

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr K.Serth and Dr A.Gossler for the GTL2 clone gift. The study was supported by NIH/NIAAA grants 8116 and the Alcohol Center Grant on Liver and Pancreas P50-011999, including the morphology core.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abu-Amero S, et al. The genetic aetiology of Silver-Russell syndrome. J Med Genet. 2008;45:193–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.053017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, et al. Curcumin and cancer: an “old-age” disease with an “age-old” solution. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:133–64. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti D, et al. Epigenetic alteration at the DLK1-GTL2 imprinted domain in human neoplasia: analysis of neuroblastoma, phaeochromocytoma and Wilms’ tumour. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1574–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarotto E, Calin GA. Potential therapeutic applications of miRNA-based technology in hematological malignancies. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2040–50. doi: 10.2174/138161208785294627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarotto E, et al. Differential effects of chemotherapeutic drugs versus the MDM-2 antagonist nutlin-3 on cell cycle progression and induction of apoptosis in SKW6.4 lymphoblastoid B-cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:595–605. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, et al. Mallory body formation is associated with epigenetic phenotypic change in hepatocytes in vivo. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, et al. Modifications in P62 occur due to proteasome inhibition in alcoholic liver disease. Life Sci. 2005;77:2594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate Mallory Denk body formation in the livers of drug-primed mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;84:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, et al. The proteasome inhibitor, PS-341, causes cytokeratin aggresome formation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2004;76:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsyte-Lovejoy D, et al. The c-Myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5330–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetatos L, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the MEG3 (DLK1/MEG3) imprinted gene in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:171–5. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.n.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti G, et al. The Air noncoding RNA: an imprinted cis-silencing transcript. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004;69:55–66. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten RJ, Davidson EH. Gene regulation for higher cells: a theory. Science. 1969;165:349–57. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3891.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadrin M, et al. Cytokeratin of apparent high molecular weight in livers from griseofulvin-fed mice. J Hepatol. 1992;14:226–31. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90162-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerchia L, De Franciscis V. Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Medicine. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:73104. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/73104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chedid A, et al. Prognostic factors in alcoholic liver disease. VA Cooperative Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, et al. Ectopic expression of DLK1 protein in skeletal muscle of padumnal heterozygotes causes the callipyge phenotype. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1858–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne EN, Delanghe JR. Diagnosing and monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma with alpha-fetoprotein: new aspects and applications. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;395:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq J, et al. Salivary gland tumors in transgenic mice with targeted PLAG1 proto-oncogene overexpression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4544–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. Non-coding RNA genes and the modern RNA world. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:919–29. doi: 10.1038/35103511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Epigenetics provides a new generation of oncogenes and tumour-suppressor genes. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:179–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, et al. DNA methylation and genomic imprinting: insights from cancer into epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:389–98. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga MF, Esteller M. Towards the human cancer epigenome: a first draft of histone modifications. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1377–81. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SW. Mechanisms of alcoholic liver injury. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:327–32. doi: 10.1155/2000/801735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XY, et al. Overexpression of p28/gankyrin in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:638–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i4.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, et al. The DNA methyltransferases associate with HP1 and the SUV39H1 histone methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003a;31:2305–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, et al. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:4035–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa R, et al. Imprinting, expression, and localisation of DLK1 in Wilms tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:145–50. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.021717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabory A, et al. The H19 gene: regulation and function of a non-coding RNA. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:188–93. doi: 10.1159/000090831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet F, et al. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300:489–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1083558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M, et al. Duplication of paternal IGF2 or loss of maternal IGF2 imprinting occurs in half of Wilms tumors with various structural WT1 abnormalities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:712–27. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiura H, et al. DNA methylation imprints on the IG-DMR of the Dlk1-Gtl2 domain in mouse male germline. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1255–60. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S, et al. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 correlates with hypermethylation of the H19 differentially methylated region in hepatoblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1891–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JP, et al. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature. 2002;416:556–60. doi: 10.1038/nature731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F, Monod J. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:318–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, et al. Role of the Dnmt3 family in de novo methylation of imprinted and repetitive sequences during male germ cell development in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2272–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T, et al. Imprinted DLK1 is a putative tumor suppressor gene and inactivated by epimutation at the region upstream of GTL2 in human renal cell carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:821–30. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulshreshtha R, et al. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1859–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner M, et al. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116–20. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavorgna G, et al. In search of antisense. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, et al. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. S-adenosylmethionine prevents Mallory Denk body formation in drug-primed mice by inhibiting the epigenetic memory. Hepatology. 2008;47:613–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.22029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, et al. A large noncoding RNA is a marker for murine hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:851–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matouk IJ, et al. The H19 non-coding RNA is essential for human tumor growth. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS, Makunin IV. Non-coding RNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 1):R17–29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT. MicroRNAs and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13:253–8. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(03)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhaul LW, et al. Molecular misreading of the ubiquitin B gene and hepatic mallory body formation. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1878–85. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanuma Y, Ohta G. Is mallory body formation a preneoplastic change? A study of 181 cases of liver bearing hepatocellular carcinoma and 82 cases of cirrhosis. Cancer. 1985;55:2400–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850515)55:10<2400::aid-cncr2820551017>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan L, et al. Mallory body forming cells express the preneoplastic hepatocyte phenotype. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006a;80:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan L, et al. Mallory body (cytokeratin aggresomes) formation is prevented in vitro by p38 inhibitor. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006b;80:228–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujundzic R. Novak, et al. Curcumin downregulates H19 gene transcription in tumor cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1781–92. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J, et al. Fat10 is an epigenetic marker for liver preneoplasia in a drug-primed mouse model of tumorigenesis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008a;84:102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J, et al. DDC regulates the expression of non-coding RNA which is prevented by feeding SAMe and betaine. The American Society of Cell Biology. 2008b [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J, et al. Betaine Prevents Mallorry-Denk Body Formation in Drug-Primed Mice by Epigenetic Mechanisms. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008c doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.11.002. [Accepted] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrego H, et al. Assessment of prognostic factors in alcoholic liver disease: toward a global quantitative expression of severity. Hepatology. 1983;3:896–905. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluszczak J, Baer-Dubowska W. Epigenetic diagnostics of cancer--the application of DNA methylation markers. J Appl Genet. 2006;47:365–75. doi: 10.1007/BF03194647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzitt K, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauler FM, et al. Silencing by imprinted noncoding RNAs: is transcription the answer? Trends Genet. 2007;23:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin LX, Tang ZY. The prognostic molecular markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:385–92. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve AE. Role of genomic imprinting in Wilms’ tumour and overgrowth disorders. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:470–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199611)27:5<470::AID-MPO14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, et al. FAT10 plays a role in the regulation of chromosomal stability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11413–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley NE, et al. The Mallory body as an aggresome: in vitro studies. Exp Mol Pathol. 2002;72:17–23. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roomi MW, et al. Preneoplastic liver cell foci expansion induced by thioacetamide toxicity in drug-primed mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;81:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H, et al. Small non-coding RNAs and genomic imprinting. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:99–108. doi: 10.1159/000090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, et al. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:435–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl CI, et al. The imprinted Air ncRNA is an atypical RNAPII transcript that evades splicing and escapes nuclear export. EMBO J. 2006;25:3565–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu S, et al. Clinical and molecular aspects of adrenocortical tumourigenesis. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:727–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels F, et al. The non-coding Air RNA is required for silencing autosomal imprinted genes. Nature. 2002;415:810–3. doi: 10.1038/415810a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohda T, et al. In situ detection of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF2) and H19 gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:49–53. doi: 10.1007/s100380050036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soppe WJ, et al. DNA methylation controls histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and heterochromatin assembly in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2002;21:6549–59. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk SJ, Kops GJ. Preventing aneuploidy: the contribution of mitotic checkpoint proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1786:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski M, et al. A new frontier for molecular medicine: noncoding RNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1756:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H, Selker EU. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2001;414:277–83. doi: 10.1038/35104508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq M, et al. Erasure of CpG methylation in Arabidopsis alters patterns of histone H3 methylation in heterochromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8823–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, et al. Promoter-restricted histone code, not the differentially methylated DNA regions or antisense transcripts, marks the imprinting status of IGF2R in human and mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2233–45. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Dutton JR. Regulation of the Wilms’ tumour suppressor (WT1) gene by an antisense RNA: a link with genomic imprinting? J Pathol. 1998;185:342–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199808)185:4<342::AID-PATH136>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AE, et al. Maternally imprinted microRNAs are differentially expressed during mouse and human lung development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:572–80. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AS, et al. DNA hypomethylation and human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:138–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, et al. Imprinting status of DLK1 gene in brain tumors and lymphomas. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:1011–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotova IY, et al. Identification of the human homolog of the imprinted mouse Air non-coding RNA. Genomics. 2008;92:464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, et al. Human microRNA clusters: genomic organization and expression profile in leukemia cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan QX, et al. Mallory body induction in drug-primed mouse liver. Hepatology. 1996;24:603–12. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatloukal K, et al. From Mallory to Mallory-Denk bodies: what, how and why? Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2033–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, et al. MicroRNAs in tumorigenesis: a primer. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:728–38. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, et al. Hypermethylation of the promoter region is associated with the loss of MEG3 gene expression in human pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2179–86. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]