Abstract

Purpose of Review

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among young people in the U.S. and represents a significant public health problem worldwide. This review focuses on recent developments in our understanding of the epidemiology and risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior.

Recent Findings

The suicide rate among children and adolescents in the U.S. has increased dramatically in recent years and has been accompanied by substantial changes in the leading methods of youth suicide, especially among young girls. Much work is currently underway to elucidate the relationships between psychopathology, substance use, child abuse, bullying, internet use, and youth suicidal behavior. Recent evidence also suggests sex-specific and moderating roles of gender in influencing risk for suicide and suicidal behavior.

Summary

Empirical research into the causal mechanisms underlying youth suicide and suicidal behavior is needed to inform early identification and prevention efforts.

Keywords: suicide, adolescents, youth, risk factors, epidemiology, attempted suicide

Introduction

This review focuses on recent developments in our understanding of the epidemiology and established and emerging risk factors of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Specifically, we conducted a PubMed search for all English-language articles published between January 2007 and May 2009 using combinations of the index terms suicide, suicide attempt, suicidal, adolescent, child*, epidemiology, and risk factors. For detailed discussions of the epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior and guidance for the management of suicidal adolescents, please see the following reviews [1-3]. The definitions of suicide and suicidal behavior developed by O'Carroll [4] and adopted by the Institute of Medicine [5] were used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of Suicidal Ideation, Communications, and Behaviora

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Suicidal Ideation | Thoughts of harming or killing oneself. |

| Suicidal Communications | Direct or indirect expressions of suicidal ideation or of intent to harm or kill self, expressed verbally or through writing, artwork, or other means. |

| Suicidal Threats | A special case of suicidal communications, used with intent to change the behavior of other people. |

| Suicide Attempt | A non-fatal, self-inflicted destructive act with the explicit or inferred intent to die. |

| Suicide | Fatal self-inflicted destructive act with explicit or inferred intent to die. |

| Suicidality | All suicide-related behaviors and thoughts including completing or attempting suicide, suicidal ideation or communications. |

O'Carroll et al. [4]

Descriptive Epidemiology of Youth Suicide and Suicidal Behavior

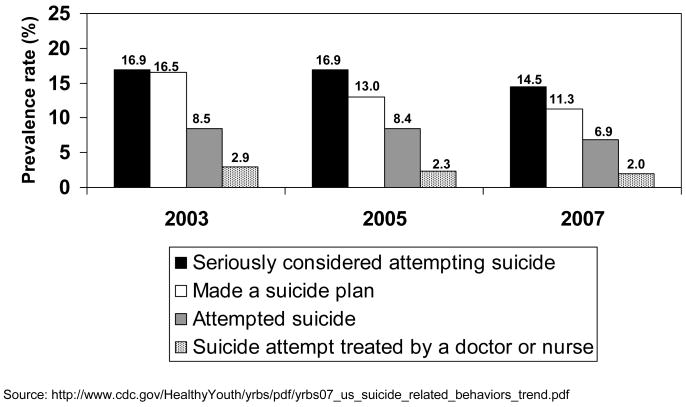

The prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in youth is high, with 14.5% of the 9th to 12th grade students in the U.S. in 2007 reporting suicidal ideation and 6.9% reporting at least one suicide attempt during the previous year (see Figure 1) [6, 7]. In 2006, the latest year for which data are available, the age-adjusted suicide rate among youth aged 10-19 years in the U.S. was 4.16 per 100,000 persons, making suicide the 3rd leading cause of death in this age group [8].

Figure 1.

Trends in the Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation, Plan, and Suicide Attempt: National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 2003-2007

Data from 7

Age and Gender

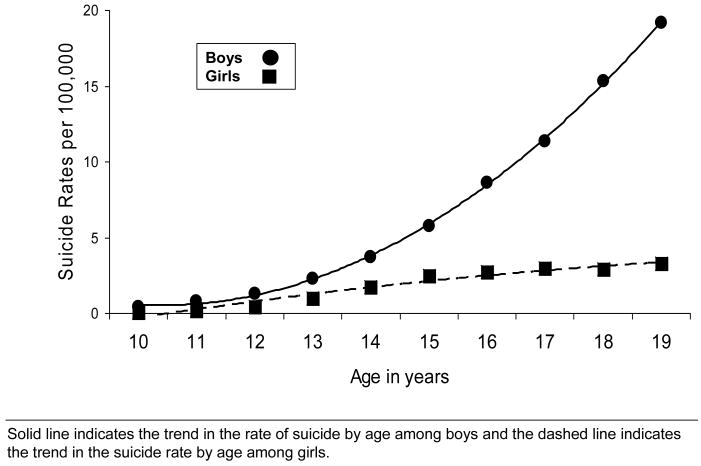

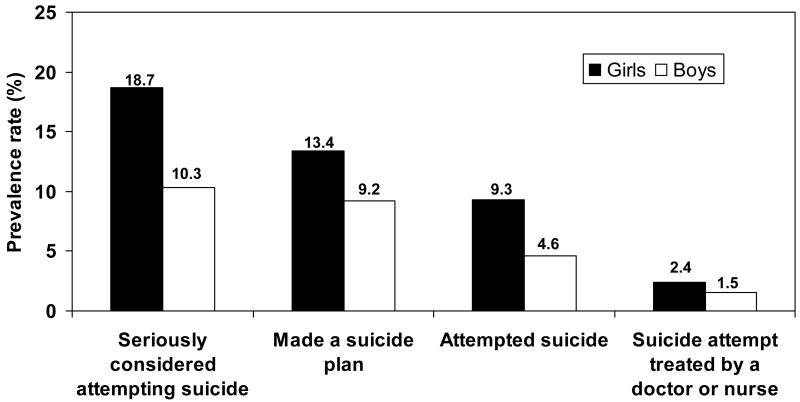

It is well established that rates of suicide and suicide-related behaviors increase with age and a gender paradox exists with regard to youth suicidal behavior: i.e., while suicide rates are higher among boys than girls, girls have higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide (see Figures 2 and 3 [6, 8]; for discussion of possible underlying reasons for age and sex differences see [9-14]).

Figure 2.

Suicide Rates by Age for Youths Aged 10-19 Years in the United States, 2000-2006 [8]

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation, Plan, and Suicide Attempt by Gender: National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 2007 [6]

Race and Ethnicity

In the U.S., rates of attempted and completed suicide are highest among Native Americans [15-17]; White youth traditionally have had higher suicide rates than non-whites, but the gap has been decreasing due to an increase in suicide among African American males [18, 19]. Compared with non-Hispanic youth, Hispanic youth in the U.S. show higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide [6], but are not disproportionately represented among suicide completers [20]. Acculturation may play a role in explaining the higher rate of attempted suicide among Hispanic adolescents, particularly young Latinas [21], although recent evidence suggests that the perceived quality of mother-daughter relations may be more predictive of adolescent suicide attempt [22].

Joe et al. [23••] recently conducted the first nationally representative study on the prevalence and psychiatric correlates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among African American and Caribbean black adolescents in the U.S. Consistent with previous studies, data from the National Survey of American Life showed that having a psychiatric disorder, especially an anxiety disorder, and living in the Northeast (compared to the South and West) were strongly associated with attempted suicide and suicidal ideation.

Using data from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey, Borges and colleagues [24•] reported the first representative estimates of the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation (11.5%), plan (3.9%), and attempted suicide (3.1%) in 12- to 17-year-olds in metropolitan Mexico City. As in previous studies, the presence of one or more mental disorders was closely linked to suicide ideation, plan, and attempt. Among youth with a history of suicidal ideation, only dysthymia was consistently related with making a suicide plan and attempted suicide.

Methods of Suicide

Firearms have traditionally been the leading suicide method among U.S. youth, followed by hanging/suffocation, and self-poisoning [1]. Case-control studies reveal that firearms are much more likely to be in the homes of suicide completers than controls and that if a gun is in the home, it is highly likely to be used as the method of suicide [25]. Restriction of access to lethal methods (e.g., more restrictive legislation regarding firearms, barriers on bridges) reduces suicide rates by those methods [26].

Recently, the CDC indicated that substantial changes have occurred in suicide methods of young people in the U.S., most notably among young females [27]. From 2003 to 2004, suicide rates by hanging/suffocation among females aged 10-14 and 15-19 increased 119% (from 0.31 to 0.68 per 100,000 persons) and 44% (from 1.24 to 1.78), respectively. Reasons for the change in suicide methods among U.S. youth are unclear.

Secular Trend in Pediatric Suicide Rates

Following a decade of steady decline, the suicide rate among U.S. youth younger than 20 years of age increased by 18 percent from 2003 to 2004—the largest single year change in the pediatric suicide rate over the past 15 years [28]. Using log-linear regression, Bridge and colleagues estimated the trend in suicide rates from 1996-2003, the expected suicide rates in 2004 and 2005, and then compared the expected number of deaths to the actual number of deaths [29•]. Although the overall suicide rate decreased by 5.3% between 2004 and 2005, observed rates were still significantly greater than expected rates, based on the 1996-2003 trend. Suggested possible contributors to the increase in youth suicides included the influence of internet social networks [30•], increases in suicide among young U.S. troops [31], and higher rates of untreated depression in the wake of recent “black box” warnings on antidepressants—a possible unintended consequence of the medication warnings, required by the FDA in 2004 [32, 33] [34•].

Psychopathology

Numerous risk factors are associated with youth suicide (Table 2). Psychiatric disorder is present in up to 80-90% of adolescent suicide victims and attempters from both community and clinical settings [1]. Both in completed and attempted suicide, the most common psychiatric conditions are mood, anxiety, conduct, and substance abuse (alcohol and drug) disorders. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders, particularly of mood, disruptive, and substance abuse disorders, significantly increases the risk for youth suicide and suicidal behavior [10, 13, 35-38].

Table 2.

Major Risk Factors for Suicide Among Adolescents

|

A recent Finnish longitudinal population-based study found that, among boys, the strongest predictor of completed suicide or making a severe suicide attempt by age 24 years was comorbid conduct and emotional (mostly anxiety) disorders at age 8 years [39••]. One in 20 boys with comorbid conduct and emotional disorders completed suicide or made a serious suicide attempt during adolescence or early adulthood, compared with only one in 250 boys without such problems. Self-reported depression symptoms at age 8 years, however, did not predict suicide outcome. Among females, no predictors of suicide outcome at the age of 8 years were found. A recent prospective cohort study found that anxious-disruptive girls and disruptive boys were more likely than their peers to attempt suicide by early adulthood, suggesting that gender-based differences in risk for suicidal behavior be considered both from a clinical perspective and in future research [40].

The Suicidality/Depression Link

Psychological autopsy studies have shown a substantial link between clinical depression and suicide in adolescence with up to 60% of adolescent suicide victims having a depressive disorder at the time of death [10, 13, 38]. Similarly, between 40-80% of adolescents meet diagnostic criteria for depression at the time of the attempt [36, 41, 42]. Depression is the main predictor of suicidal ideation [36, 43]. In clinically referred samples, up to 85% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) or dysthymia (i.e., chronic, but less severe depression) will have suicidal ideation, 32% will make a suicide attempt sometime during adolescence or young adulthood [44], 20% will make more than one attempt [45], and by young adulthood, 2.5% to 7% will commit suicide [46]. The association of prior suicidal behavior and depression has been shown to increase the risk for a repeated suicide attempt [47, 48] and suicide [10].

Recent studies confirm prior research indicating that suicidal thoughts during adolescence significantly increase the adult risk of psychiatric problems, and are the gateway to attempted suicide, and suicide [49], [50, 51]. These findings suggest that ameliorating suicidal ideation in adolescence offers hope of reducing acute distress and changing the life course of affected individuals.

Fergusson et al. [52] examined the impact of recurrence of major depression in adolescence on outcomes at ages 21-25 years. Using data from a 25-year longitudinal study of a birth cohort of New Zealand, the authors found a dose-response relationship between the number of depressive episodes between 16-21 years of age and adverse adult outcomes, including suicidal ideation and attempted suicide, even after controlling for potential confounders. These findings suggest that early identification and treatment of major depression may reduce the risk of future suicidal behavior.

Alcohol and Drug Use

Substance abuse (alcohol/drug abuse) disorders contribute substantially to risk of suicide, especially in older adolescent males when co-occurring with mood disorder or disruptive disorders [10, 13, 38]. Recently, Aseltine et al. [53•] examined the relationship between heavy episodic drinking (HED) and adolescent suicide attempts. They found that adolescents who were 13 years or younger and who participated in HED were at 2.6 times greater risk of reporting a suicide attempt as compared to those who did not participate in HED. For those youth who were 18 years and older, HED increased their suicide attempt risk by 1.2 times as compared to adolescents of this same age who did not participate in HED. Schilling and colleagues [54] found that drinking while feeling down resulted in a threefold increase in the risk of self-reported suicide attempts.

Family Factors

Family factors, including parental psychopathology, family history of suicidal behavior, family discord, loss of a parent to death or divorce, poor quality of the parent-child relationship, and maltreatment, are associated with an increased risk of adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior [1].

Family Constellation

Increasing duration of exposure to a single-parent household before the age of 16 years was significantly associated with higher rates of anxiety disorder between the ages of 21-25 years. Duration of exposure, however, was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation or attempted suicide [55].

Family History of Suicide Attempt

There is strong and convergent evidence that suicidal behavior is familial, and perhaps, genetic, and that the liability to suicidal behavior is transmitted in families independently of psychiatric disorder [56]. A recent prospective study of early-onset suicidal behavior found a higher relative risk (RR=4.4) of incident suicide attempts in offspring of parents with mood disorders who made suicide attempts, compared with offspring of parents with mood disorders who had not made attempts [57]. Offspring mood disorder and impulsive aggression and parental history of sexual abuse were independent predictors of incident suicide attempts.

Sexual and Physical Abuse

Exposure to child sexual abuse and child physical abuse leads to a significant increase in the occurrence of a variety of poor mental health outcomes, including suicidal ideation and behavior, experienced between ages 16-25, [58]. The authors found that exposure to child sexual abuse had a more deleterious effect on mental health outcomes than exposure to only child physical abuse. In another study, approximately 50% and 33% of suicide attempts among women and men, respectively, were attributable to the experience of childhood adversity (physical abuse, sexual abuse, witnessed domestic violence) [59•], indicating that even a small reduction in these childhood experiences could have a dramatic effect on reducing the prevalence of suicide attempts in the general population.

When a child experiences both child abuse and parental divorce versus only parental divorce, there is a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of a suicide attempt later in life [60]. This association, however, was attenuated after controlling for parental psychopathology.

Brezo et al. [61] conducted a longitudinal cohort study to determine the relationship between childhood abuse and later suicide attempts. Non-abused children were less likely to have non-fatal suicide behaviors as compared to those who experienced abuse. Sexual abuse by an immediate family member, repeated sexual abuse incidents, and greater severity of abuse conferred an increased risk of suicide attempts.

Salzinger and colleagues [62] followed two sets of urban school children over a period of 4 years (time 1: average age 10. 5 years, n=100 abused and 100 non-abused; time 2: average age 16.5 years, n=78 abused and 75 non-abused). They found that preadolescent physical abuse was an independent predictor of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide; only internalizing behaviors mediated the robust relationship between physical abuse and suicidal ideation.

Change of Residence

Adolescents aged 11-17 years who frequently moved during childhood were more likely to make suicide attempts during adolescence, and the more often they had moved, the more elevated their risk, even after controlling for potential confounders at birth and during upbringing [63••]. There was a dose-response relationship between number of moves and risk of attempted suicide: youth who had moved three to five times were 2.3 times as likely to have attempted suicide compared with those who had never changed residences, while those who had moved more than 10 times were 3.3 times as likely to attempt suicide, controlling for birth order, birthplace, and paternal and maternal factors. Controlling for additional child and parent factors attenuated these specific associations. Analyses of suicide completers revealed a similar association between change of residence and suicide.

Sexual Orientation

Youth who report same-sex sexual orientation are at greater risk than their peers to have attempted suicide, and this risk persists even after controlling for other suicide risk factors, including alcohol abuse, depression, family history of suicide attempts, and prior victimization [64]. A recent study of family response to an adolescent “coming out process” reported that family rejection or negative family reaction to an adolescent who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual was associated with 8-fold greater likelihood of attempted suicide compared to adolescents who experienced minimal or no family rejection [65].

Bullying

Klomek and colleagues [66•] found that boys who were both bullies and victims of bullying had a higher likelihood of suicidal behavior as compared with those who did not exhibit bullying behaviors or who were only victims. For the girls, there was a different effect of bullying; girls who were victims of bullying were more likely to exhibit suicidal behaviors as compared to those who were neither bullies nor victims. Barker et al. [67] examined the developmental trajectories of bullying and victimization during adolescence on delinquency and self-harm in late adolescence. For both boys and girls, those in the bully-victim trajectory showed significantly higher levels of self-harm than their same-sex counterparts in all of the other trajectories. The girls in the bully-victim trajectory had higher rates of self harm than their male counterparts.

Advances in technology have helped to create a new form of bullying: cyber bullying. Cyber-bullying can occur through emails, texting on cell phones, and posts on internet social sites (e.g., Facebook, MySpace, Twitter) and can be perpetrated by other adolescents or adults, as has been recently reported [68]. At this time, research on cyber-bullying and suicide has not been published.

Internet and Adolescent Suicide

The internet can be both detrimental and helpful in relation to suicide. Two studies examined the extent to which information on methods of committing suicide and pro-suicide websites could be found using different search engines [30, 69]. Biddle and colleagues [30•] found that 240 of the 480 suicide sites provided some information on how to commit suicide. Recupero and colleagues [69] reviewed 373 web pages and found 11.0% to contain pro-suicide information, 30.8% to contain both pro- and anti-suicide information, 29.2% to contain anti-suicide information, and 9.1% could not be evaluated. Approximately 20% of the sites that did not contain suicide-specific information had a hyperlink or advertisement for online pharmacies selling medications used for committing suicide.

Conclusion

This review provides an overview of the most recent research on adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior with a specific focus on epidemiological, psychiatric, psychological, and environmental factors. The informed clinician will optimally be able to use these findings to develop a more comprehensive understanding and assessment of adolescent suicide risk factors, which may promote early assessments that lead to targeted interventions, thus reducing future risk of poor mental health outcomes and suicidal behaviors.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3/4):372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer D, Pfeffer C. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:24S–51S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shain BN. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007 Sep;120(3):669–676. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris RW, et al. Beyond the Tower of Babel: a nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26(3):237–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, et al. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008 Jun 6;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [6/19/2009];2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: http://www.cdc.yrbss.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [6/19/2009];Source of data from WISQARS is the National Vital Statistics System from the National Center for Health Statistics. online. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 9.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Youth suicide attempts: a social and demographic profile. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998 Jun;32(3):349–357. doi: 10.3109/00048679809065527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, et al. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;38(12):1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med. 2000 Jan;30(1):23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groholt B, Ekeberg O, Wichstrom L, et al. Suicide among children and younger and older adolescents in Norway: a comparative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998 May;37(5):473–481. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 Dec;53(12):1155–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson RN. National Vital Statistics Reports. 16. Vol. 50. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Deaths: leading causes for 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borowsky IW, Resnick MD, Ireland M, et al. Suicide attempts among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: risk and protective factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Jun;153(6):573–580. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace JD, Calhoun AD, Powell KE, et al. Violence Surveillance Series, No. 2. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 1996. Homicide and Suicide Among Native Americans, 1979-1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joe S, Kaplan MS. Firearm-related suicide among young African-American males. Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Mar;53(3):332–334. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaffer D, Gould M, Hicks RC. Worsening suicide rate in black teenagers. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Dec;151(12):1810–1812. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demetriades D, Murray J, Sinz B, et al. Epidemiology of major trauma and trauma deaths in Los Angeles County. J Am Coll Surg. 1998 Oct;187(4):373–383. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zayas LH, Lester RJ, Cabassa LJ, et al. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005 Apr;75(2):275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zayas LH, Bright CL, Alvarez-Sanchez T, et al. Acculturation, familism and mother-daughter relations among suicidal and non-suicidal adolescent Latinas. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009 Jul;30(3-4):351–369. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23••.Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, et al. 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;48(3):271–282. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first national study on the prevalence and psychiatric correlates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among African American and Caribbean black adolescents in the U.S.

- 24•.Borges G, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, et al. Suicide ideation, plan, and attempt in the Mexican adolescent mental health survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;47(1):41–52. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815896ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study to report representative estimates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among 12-17 year olds in metropolitan Mexico City.

- 25.Brent DA, Bridge JA. Firearms availability and suicide: Evidence, interventions, and future directions. Am Behav Sci. 2003 May;46(9):1192–1210. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005 Oct 26;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubell KM, Kegler SR, Crosby AE, et al. Suicide trends among youths and young adults aged 10-24 years-United States, 1990-2004. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56:905–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton BE, Minino AM, Martin JA, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2005. Pediatrics. 2007;119:345–360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH, et al. Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1025–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed that the spike in suicide rates from 2003 to 2004 among U.S. youth aged 10-19 years was not a single-year anomaly.

- 30•.Biddle L, Donovan J, Hawton K, et al. Suicide and the internet. BMJ. 2008;336:800–802. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39525.442674.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found that searches on Internet sites about suicide are more likely to be pro-suicide than to provide help or support.

- 31.Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise: military, scientists work to stem the tide. JAMA. 2009 Mar 18;301(11):1111, 1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, et al. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:884–891. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al. Spillover Effects on Treatment of Adult Depression in Primary Care After FDA Advisory on Risk of Pediatric Suicidality With SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;164(8):1198–1205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;66(6):633–639. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found that both pharmacological and non-pharmacological depression treatment among youth and adults continued to decline following the FDA's boxed warning on antidepressant medications in 2004.

- 35.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 1996;3:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998 Sep;37(9):915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renaud J, Brent DA, Birmaher B, et al. Suicide in adolescents with disruptive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Jul;38(7):846–851. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafii M, Steltz-Lenarsky J, Derrick AM, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders in the post-mortem diagnosis of completed suicide in children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 1988 Nov-Dec;15(3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39••.Sourander A, Klomek AB, Niemela S, et al. Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts: findings from the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;66(4):398–406. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found that one in 20 boys with comorbid conduct and emotional disorders completed suicide or made a serious suicide attempt during adolescence or early adulthood, compared with only one in 250 boys without such problems. No predictors of suicide outcome were found among girls.

- 40.Brezo J, Barker ED, Paris J, et al. Childhood trajectories of anxiousness and disruptiveness as predictors of suicide attempts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Nov;162(11):1015–1021. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Psychiatric illness in a New Zealand sample of young people making serious suicide attempts. N Z Med J. 1998 Feb 27;111(1060):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Reboussin BA, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses of previous suicide attempters, first-time attempters, and repeat attempters on an adolescent inpatient psychiatry unit. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998 Sep;37(9):924–932. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Silverman AB, et al. Early psychosocial risks for adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995 May;34(5):599–611. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovacs M, Goldston D, Gatsonis C. Suicidal behaviors and childhood-onset depressive disorders: a longitudinal investigation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993 Jan;32(1):8–20. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrington R, Bredenkamp D, Groothues C, et al. Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent depression. III. Links with suicidal behaviours. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994 Oct;35(7):1309–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrington R, Fudge H, Rutter M, et al. Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent depression. II. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990 May;47(5):465–473. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfeffer CR, Klerman GL, Hurt SW, et al. Suicidal children grow up: rates and psychosocial risk factors for suicide attempts during follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993 Jan;32(1):106–113. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Wartella ME, et al. Adolescent psychiatric inpatients' risk of suicide attempt at 6-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993 Jan;32(1):95–105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinherz HZ, Tanner JL, Berger SR, et al. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;163(7):1226–1232. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, van der Ende J, et al. Long-term associations of childhood suicide ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Nov;46(11):1473–1481. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318149e66f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kerr DC. Replicated prediction of men's suicide attempt history from parent reports in late childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;47(7):834–835. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817395e4. author reply 835-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;191:335–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53•.Aseltine RH, Jr, Schilling EA, James A, et al. Age variability in the association between heavy episodic drinking and adolescent suicide attempts: findings from a large-scale, school-based screening program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;48(3):262–270. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bce8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found age-dependent risks of adolescent suicide attempt associated with heavy episodic drinking.

- 54.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Jr, Glanovsky JL, et al. Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Apr;44(4):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;64(9):1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Semin Med Gen) 2005;133C:13–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melhem NM, Brent DA, Ziegler M, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicidal behavior: familial and individual antecedents of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;164(9):1364–1370. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2008 Jun;32(6):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59•.Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, et al. Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. Am J Public Health. 2008 May;98(5):946–952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found that a large percentage of suicide attempts among men and women was attributable to childhood adversity.

- 60.Afifi TO, Boman J, Fleisher W, et al. The relationship between child abuse, parental divorce, and lifetime mental disorders and suicidality in a nationally representative adult sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2009 Mar;33(3):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brezo J, Paris J, Vitaro F, et al. Predicting suicide attempts in young adults with histories of childhood abuse. Br J Psychiatry. 2008 Aug;193(2):134–139. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salzinger S, Rosario M, Feldman RS, et al. Adolescent suicidal behavior: associations with preadolescent physical abuse and selected risk and protective factors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Jul;46(7):859–866. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63••.Qin P, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Frequent change of residence and risk of attempted and completed suicide among children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;66(6):628–632. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found that frequent changes of residence were associated with increased risks of attempted and completed suicide among children and adolescents.

- 64.Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2001 Aug;91(8):1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66•.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemela S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;48(3):254–261. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examined the relationship between bullying, victimization, and suicidal behavior for preadolescent boys and girls.

- 67.Barker ED, Arseneault L, Brendgen M, et al. Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: relations to delinquency and self-harm. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Sep;47(9):1030–1038. doi: 10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eec98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steinhauer J. The New York Times; [6/21/2009]. Verdict in MySpace Suicide Case. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/27/us/27myspace.html. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Recupero PR, Harms SE, Noble JM. Googling suicide: surfing for suicide information on the Internet. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Jun;69(6):878–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]