Abstract

Aging and DNA polymerase β deficiency (β-pol+/−) interact to accelerate the development of malignant lymphomas and adenocarcinoma and increase tumor bearing load in mice. Folate deficiency (FD) has been shown to induce DNA damage repaired via the base excision repair (BER) pathway. We anticipated that FD and BER deficiency would interact to accelerate aberrant crypt foci (ACF) formation and tumor development in β-pol haploinsufficient animals. FD resulted in a significant increase in ACF formation in wild type (WT) animals exposed to 1,2-dimethylhydrazine, a known colon and liver carcinogen; however, FD reduced development of ACF in β-pol haploinsufficient mice. Prolonged feeding of the FD diet resulted in advanced ACF formation and liver tumors in wild type mice. However, FD attenuated onset and progression of ACF and prevented liver tumorigenesis in β-pol haploinsufficient mice, i.e. FD provided protection against tumorigenesis in a BER-deficient environment in all tissues where 1,2-dimethylhydrazine exerts its damage. Here we show a distinct down-regulation in DNA repair pathways, e.g. BER, nucleotide excision repair, and mismatch repair, and decline in cell proliferation, as well as an up-regulation in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, proapoptotic genes, and apoptosis in colons of FD β-pol haploinsufficient mice.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cancer/Colon, DNA/Damage, DNA/Repair, Gene/Knockout, Gene/Regulation, Metabolism/Folate, Vitamins and Cofactors

Introduction

Folate deficiency is an important public health concern because of the role folate plays in the development of many different health problems, including neural tube defects, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer disease, and cancer, specifically colon cancer. It has been proposed that the carcinogenic properties of folate deficiency may be related to a decrease in DNA methylation, perhaps as a function of reduced S-adenosylmethionine levels, an increase in the uracil content of DNA, or an increase in oxidative stress by alterations in thiol switches. Folate deficiency has also been shown to increase (in cells, animal models, and humans) levels of single strand breaks (1–5), micronucleus formation (6, 7), chromosomal aberration (8, 9), and mutation frequency (10, 11), all potentially downstream effects of high levels of uracil in DNA and oxidative damage to DNA.

The DNA repair pathway for removal of uracil and oxidized bases is the base excision repair (BER)2 pathway. The BER pathway is believed to repair small, non-helix-distorting lesions in the DNA. It has been estimated to be responsible for the repair of as many as one million nucleotides per cell per day (12), stressing its importance in the maintenance of genomic stability. It has been suggested that BER has evolved in response to in vivo exposure of DNA to reactive oxygen species and endogenous alkylation, and that this pathway suppresses spontaneous mutagenesis (13). In the initial elucidation of the BER pathway the following steps were involved: (i) removal of the damaged base by a DNA glycosylase; (ii) incision of the phosphate backbone by an endonuclease; (iii) synthesis of new DNA by a polymerase; (iv) excision of the deoxyribose phosphate moiety; and (v) ligation. This remains the predominant BER pathway and is clearly the pathway for repair of uracil. DNA polymerase β (β-pol) performs the polymerization steps in the predominant short patch BER pathway and appears to perform the rate-limiting step, by virtue of its deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity (14). In the process of uracil removal and repair of oxidized bases, a transient formation of a DNA single strand break occurs.

Our laboratory has shown that haploinsufficiency in β-pol would result in persistence of the DNA single stand breaks, where this persistence could result in DNA double strand breaks and chromosomal aberration (15). In addition, these animals exhibit an accumulation of spontaneously arising single strand breaks and chromosomal aberrations with age. Furthermore, in response to alkylating and oxidizing agents, an even greater accumulation of single strand breaks and chromosomal aberrations, as well as an increase in mutation frequency, are observed in these mice (15). Moreover, β-pol haploinsufficient mice display an acceleration of normal, age-related tumors, e.g. lymphomas, developing alongside an increased susceptibility to epithelial tumors, e.g. adenocarcinomas, which do not typically occur at a high incidence in C57BL/6 mice (16).

Based on the striking similarities between DNA damage induced by folate deficiency and that induced by a reduction in BER capacity, we suggest a strong association between BER and folate. We have reported previously that folate deficiency overwhelms the capacity of BER through the inhibition of up-regulation of β-pol (17). It is feasible that the inability to induce β-pol when folate is deficient results in a functional BER deficiency, providing a logical explanation for the phenotype induced by folate deficiency. Although a tight correlation between DNA damage and cancer exists, it is necessary to evaluate preneoplastic lesions and tumors arising in response to the interaction between β-pol loss and folate deficiency. The purpose of this study is to determine whether β-pol haploinsufficiency accelerates the development and/or aggressiveness of these lesions in colon and liver in response to the carcinogen, 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH). This study has important human health implications, as polymorphisms within the human population may render individuals haploinsufficient for β-pol and increase cancer risk by reducing their DNA damage tolerance.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Experiments were performed in young 4 to 6-month-old C57BL/6-specific pathogen-free male mice and mice heterozygous for the DNA polymerase β gene (β-pol+/−) (16). All practices performed on animals were in agreement with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Mice heterozygous for the DNA polymerase β gene (β-pol+/−) were created in Rajewsky's laboratory (18) by deletion of the promoter and the first exon of the β-pol gene. Homozygous deletion of β-pol results in embryonic lethality, but the heterozygous mice survive and seem to be normal and are fertile; there is no retardation in food intake, weight gain, or growth rate. All mice were backcrossed into C57BL/6 for at least 20 generations. The genotype of the mice was determined by Southern blot analysis as described by Cabelof et al. (15). The Wayne State University Animal Investigation Committee approved the animal protocol. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle and given water ad libitum.

Diets and Carcinogenic Treatment

After acclimation for 7 days, wild type (WT) and β-pol+/− mice were randomly assigned to two dietary groups: a folate-adequate (FA) or folate-deficient (FD) AIN93G-purified isoenergetic diet (Dyets, Inc., Lehigh Valley, PA) as described previously (17). The FA group received a folate-adequate diet containing 2 mg/kg of folic acid. The FD group received a folate-deficient diet containing 0 mg/kg of folic acid. Diets were stored at −20 °C. 1% succinyl sulfathiazole was added to all diets. One week after commencement of food ingestion, randomly selected mice from both FA and FD were injected intraperitoneally with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine HCl (DMH, 30 mg/kg body weight) in 10 mmol/liter of NaHCO3 (Fisher Scientific) once a week for 6 weeks (Fig. 2A). Both food intake and body weights were checked twice weekly to monitor for signs of toxicity, e.g. weight loss, and the diets continued for 12 weeks.

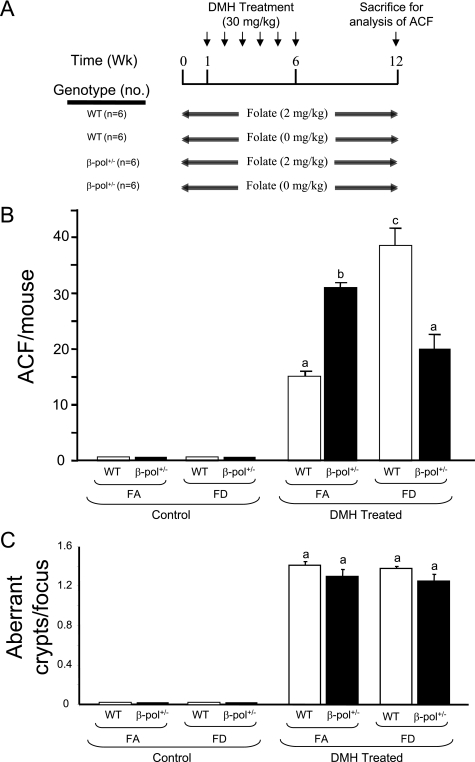

FIGURE 2.

A, experimental design: WT and β-pol+/− mice were fed either a folate-adequate (2 mg/kg, FA) or a folate-deficient (0 mg/kg, FD) diet for 12 weeks. After 1 week of ingestion of the respective diets, mice were injected with 30 mg/kg body weight of DMH for 6 weeks. Six weeks after the final injection, animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. B and C, ACF formation and crypt multiplicity in the colon of β-pol+/− mice consuming a folate-deficient diet. WT and β-pol+/− received either a FA or FD diet and were subjected to either no treatment (control) or intraperitoneal treatment with DMH for 6 weeks at 30 mg/kg body weight (DMH treated). After sacrifice, colons were processed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Colons were analyzed under light microscopy to visualize the number of ACF per mouse colon (ACF/mouse) (B) and the number of crypts per focus (C). Bars with different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. Bars indicate S.E.

Aberrant Colonic Crypt (ACF) Analysis

Animals were anesthetized under CO2 asphyxiation, the abdominal cavity was opened and the colon excised, rinsed with cold phosphate-buffered saline, cut longitudinally, and fixed flat overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The colonic crypts were stained with 2 g/liter of methylene blue in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 min. The number of ACF and aberrant crypts per foci were determined by light microscopy at ×10 magnification in a blinded manner.

Real Time PCR

Total RNAs were isolated from the colon mucosa of mice using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer's protocol. cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using random hexamer primers (Promega, Madison, WI) and purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen). The levels of cDNAs were quantified using a LightCycler real time PCR machine (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). PCR contained 3 μl of purified cDNA, 12.5 μl of qPCR master mix, and 0.5 μmol/liter each of sense and antisense primers (Roche) (Table S1 and supplemental data 1). For all amplifications, PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 30 s, with a melting curve analysis from 60 to 95 °C to confirm specificity. External standards were prepared by amplification of cDNAs for each gene. The amplicons were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector, linearized with appropriate restriction enzyme, and used to prepare external standard curves. The level of each transcript was normalized to Gapdh. Results are expressed as mean values from five animals per experimental group.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using 200 μg of nuclear protein as previously described (19). Upon completion of SDS-PAGE, the region containing the protein(s) of interest was excised and prepared for Western blot analysis, whereas the remaining portion of the gel was stained with GelCode blue stain reagent (Pierce Biotechnology) to ensure equal protein loading. Western analysis was accomplished using affinity purified polyclonal antisera developed against mouse β-pol. As an internal control for protein loading, membranes were reprobed with anti-Lamin B antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The bands were visualized and quantified using a ChemiImagerTM System (AlphaInnotech, San Leandro, CA) after incubation in SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology). Data are expressed as the integrated density value of the band per μg of protein loaded.

Microarray Assays

Total RNAs were isolated from the colon mucosa of mice using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's protocol. RNA samples were quantified with NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE), and the 260/280 ratio in the 2.0–2.2 range was defined as acceptable. A quality check of the total RNA was performed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). One microliter of total RNA sample was applied to a RNA 6000 NanoChip, and the assay was run on the Bioanalyzer to determine whether the 18 S and 28 S ribosomal bands were defined and to ensure no RNA degradation was present. Optimal concentration used to check the RNA quality is 250 ng/μl.

Microarray expression profiling was conducted by the Microarray & Bioinformatics Facility Core at the Wayne State University (Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Detroit, MI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A balanced block experimental design was used: 4 microarrays were completed for each comparison, with each microarray representing 1 randomly selected labeled mucosal sample from each experimental group paired with 1 randomly selected FAWT-labeled mucosal sample, i.e. in total 4 mucosal RNA samples from FDWT co-hybridized with 4 FAWT, 4 FDWT DMH-treated co-hybridized with 4 FAWT, and 4 FD β-pol+/− DMH co-hybridized with 4 FAWT treated, representing 4 microarrays for each experimental comparison. Samples on a given array were oppositely labeled with Alexa 647 and Alexa 555 dyes. The four microarrays for a given group (i.e. WT untreated, WT DMH, or β-pol+/− DMH treated) represent samples from eight separate mice, providing consideration of biological variation. In total, 12 arrays representing 24 mice (8 WT, 8 WT DMH-treated, 8 β-pol+/− DMH-treated) were completed. Dye swaps were used to account for dye bias effects such that of the four arrays in a given phenotype group, two had FD-treated samples labeled with Alexa 647 co-hybridized with control samples labeled with Alexa 555, whereas the other two arrays within the same phenotype group had opposite dye orientations. Microarrays were scanned using the Agilent dual laser DNA microarray scanner model G2565AA, with 10-μm resolution.

Microarray Gene Profile Analysis

Microarray image analysis was performed with Agilent Feature Extraction software, version A.5.1.1. Hierarchal Clustering analysis was performed using GeneSpringGX V10 (Agilent Technologies) software, and the parameters were set for centroid linkage, which calculates the euclidean distance between the respective centroids of two clusters. The false discovery rate for FDWT was 5.1%, 1.7% for FDWT DMH treated, and 0.39% for FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated experimental groups. Heat maps were created by inputting accession numbers of differentially expressed genes at p < 0.001 for FDWT and FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated experimental groups through the DAVID functional annotation. Outputs revealed gene ontologies of differentially expressed genes, which were then compared with created differentially expressed gene lists of DAVID biological processes, such as apoptosis and DNA repair. Data sets were then combined for FDWT and FD β-pol+/− DMH treated to 1 large data set to create heat maps for each biological function. Gene ontology analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology Tree Machine (GOTM) (Bioinformatics, Vanderbilt University), and applying differentially expressed genes as depicted in the heat maps. We chose a single gene set analysis, where GOTM compares the distribution of single gene sets in each GO category to those in an existing reference gene list from the mouse genome, identifying GO categories with statistically significant enriched gene numbers as determined by the hypergeometric test (p < 0.01) (20, 21). Real time quantitative RT-PCR was used to confirm the data obtained for selected genes in DNA repair pathways as described above.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-mediated Nick-end Labeling of Apoptotic Cells in Situ

Colon tissues were dissected, opened longitudinally, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, then cut into 5 μm-thick sections. Sections were put on slides for the in situ terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) (CHEMICON International Inc., Temecula, CA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Cells with positive staining (brown staining) were considered apoptotic cells and the number of apoptotic cells was determined as the percentage per crypt.

5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdUrd) Staining of Proliferating Cells in Situ

Two hours prior to CO2 asphyxiation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with a BrdUrd solution (10 mol/liter, 1 ml/100 g of body weight) (5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine Labeling and Detection Kit II, Roche Diagnostics) to immunostain proliferating cells, following the manufacturer's instructions for paraffin-embedded tissues. Briefly, after CO2 asphyxiation, as mentioned above, colons were excised and fixed in formalin. The tissue was then embedded in paraffin and sections of 3–5 μm were cut longitudinally the full-length of the colon. Tissues were incubated in 10 μmol of anti-BrdUrd monoclonal antibody for 1 h at 37 °C followed by incubation with anti-mouse Ig-alkaline phosphatase. The labeling index was used to quantify cell proliferation, defined as the percentage of BrdUrd-positive cells per crypt.

Tumor Analysis

All animals were sacrificed at 40 weeks after the last dose of DMH, by asphyxiation with carbon dioxide, and all organs and tissues were examined for grossly visible lesions. Liver and colon tissues, including gross abnormalities, were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, trimmed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to a thickness of 5–6 μm, stained with H&E, and examined microscopically. Preparation of slides for histopathology evaluation was performed by pathologists at the Department of Pathology, Wayne State University.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance between means was determined using analysis of variance, followed by the Fisher's least significant difference test where appropriate (22). p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Induction of ACF Formation in DNA Polymerase β Haploinsufficient Mice in Response to DMH

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of BER deficiency on colon carcinogenesis in an animal model. In the first series of experiments, we determined the impact of β-pol heterozygosity on the development and progression of ACF in DNA polymerase β heterozygous knock-out mice of C57BL/6 background, characterized previously by our laboratory (15). We have previously observed a deficiency in β-pol gene expression in various tissues of β-pol+/− mice (brain, liver, spleen, and testes) with a concurrent decline in BER capacity (15). As shown in Fig. 1A, in this study we have confirmed a similar decline in expression of the β-pol gene in the colon mucosa of the β-pol+/− mice suggesting a parallel decline in BER activity in the colon of these mice.

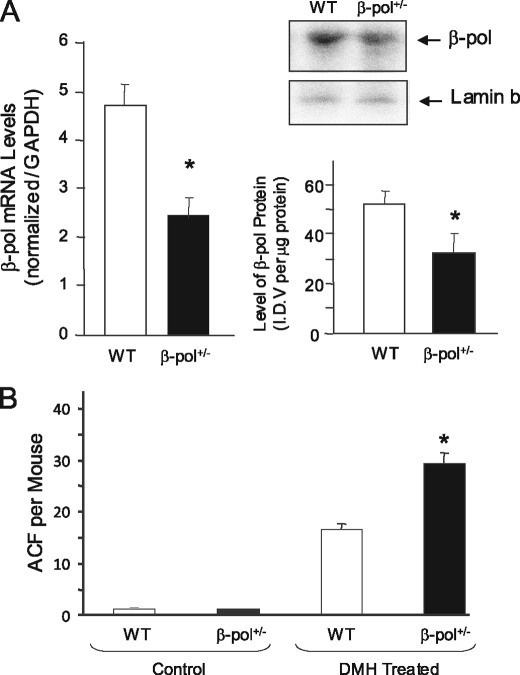

FIGURE 1.

Impact of β-pol heterozygosity on expression of β-pol in colon mucosa and ACF formation in colon of mice treated with DMH. A, analysis of β-pol expression, mRNA, and protein levels in mucosa from wild type and β-pol haploinsufficient mice. Expression of the β-pol gene was determined using a real time PCR technique and the level was normalized based on Gapdh expression. The protein level was quantified using Western blot analysis and normalized based on the Lamin b protein level. B, WT mice and β-pol haploinsufficient mice received either no treatment (controls) or intraperitoneal treatment with DMH for 6 weeks at 30 mg/kg body weight (DMH treated). Colons were processed after CO2 asphyxiation of mice as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Colons were analyzed under light microscopy to visualize the number of ACF per mouse colon (ACF/mouse). Bars, S.E., *, p < 0.01.

It is well established that carcinogen-induced ACF are early indicators of initiation of colon cancer in animal models (24–26). In this study, we utilized DMH, an established colon and liver carcinogen. It is proposed that DMH converts to the active metabolites azoxymethane and methylazoxy methanol in the liver, which are then transported to the colon via blood and bile (27). DMH in these tissues extends its damage to DNA by induction of alkylation damage (O6-MeG and N7-MeG) as well as oxidative damage. We have previously demonstrated that the β-pol+/− mouse is not sensitive to the O6-MeG lesion (removed by direct reversal), but is sensitive to the N7-MeG lesion processed by the BER pathway (28). Additionally, we have observed an increased accumulation of DNA single strand breaks in the β-pol+/− mouse in response to oxidative stress, as compared with its wild type counterpart (15). Thus, we postulated that β-pol haploinsufficiency may predispose animals to increased colon carcinogenicity and induce development of ACF in response to DMH. At the outset of the current study, mice were injected with 30 mg/kg body weight of DMH for 6 weeks to induce ACF. Six weeks after the final injection, the mice were sacrificed and the level of ACF in the colon was determined. As shown in Fig. 1B, wild type and β-pol haploinsufficient-untreated mice did not display any ACF in their colon. Thus, β-pol haploinsufficiency and subsequent deficiency in BER capacity is not enough to induce ACF in mice, suggesting that β-pol is a low penetrance gene, requiring a high penetrance environmental insult, e.g. DMH or nutritional deficiency, for the damage to accumulate. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1B, β-pol+/− DMH-treated mice exhibited a significantly higher level of ACF formation (67% higher) as compared with wild type counterparts (15.4 ± 1.8 versus 29.7 ± 1.4, for wild type and β-pol+/− mice, respectively, p < 0.01). These findings indicate that β-pol haploinsufficient mice are more sensitive to DMH, i.e. β-pol+/− animals show an inability to respond to oxidative stress and alkylation damage as compared with their wild type littermates. Interestingly, no significant differences in ACF size and aberrant crypts per focus were observed in these animals. Having confirmed these findings, we were interested in the effect of folate deficiency in a BER-deficient environment on the response to DMH.

Impact of Folate Deficiency and β-pol Haploinsufficiency on ACF Formation in Colon

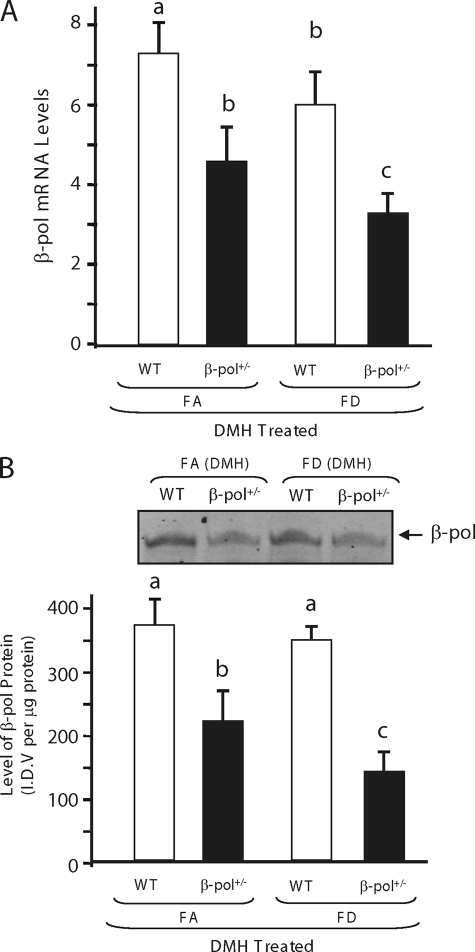

Folate deficiency has been suggested to impact on the S-adenosylmethionine/S-adenosyl homocysteine ratio (28), increase uracil incorporation into DNA (a substrate for BER pathway), and induce oxidative stress in animals. Subsequently, to elicit the role of folate deficiency on ACF formation in wild type and β-pol+/− animals, animals were fed either a FA (2 mg/kg of folic acid) or FD (0 mg/kg of folic acid) diet as outlined in Fig. 2A. To induce severe folate deficiency, 1% succinyl sulfathiazole was added to the diet deficient in folic acid to prevent synthesis of folic acid in the gut by bacteria. The animals' food intake and body weight were monitored weekly. Folate deficiency for 8 weeks did not affect body weight, whereas it reduced the plasma folate level by 90% as determined by a SimulTRAC-SNB radioassay kit for vitamin B12 (57Co) and folate (125I) per the manufacturer's protocol (ICN Diagnostics, Orangeburg, NY) as described previously (17). In addition, under these conditions we observed an approximate 40% decrease in colon folate concentration when folate was deficient, a finding similar to those of others (29). After 1 week on each diet, respectively, the wild type and β-pol+/− mice were injected with DMH once per week for 6 weeks (Fig. 2A). Six weeks after the final injection, DMH-treated and control mice were sacrificed and the levels of ACF in colons were determined. Interestingly, no ACF were observed in control mice fed a folate-adequate and/or folate-deficient diet. Thus, β-pol haploinsufficiency in conjunction with folate deficiency was not enough to induce ACF formation in untreated mice. However, DMH-induced ACF were observed in all DMH-treated animals. As observed by other laboratories (30, 31), folate deficiency resulted in a significant increase in ACF formation in wild type animals treated with DMH as compared with the FA counterpart (15.4 ± 1.8 versus 37.6 ± 5.2, for FA and FD mice, respectively, p < 0.01), i.e. folate deficiency predisposes mice to increased colon carcinogenesis in response to DMH. As shown in Fig. 2B, DMH-induced ACF were confirmed and significantly higher in FA β-pol+/− mice as compared with their wild type littermates. Based on these findings and in view of the fact that FD resulted in further decline in β-pol expression (Fig. 3A) and protein levels (Fig. 3B) in colon mucosa, we anticipated that β-pol haploinsufficient mice would display a dramatic development of ACF when folate is deficient. However, we observed a significant reduction in the formation of ACF in β-pol+/− mice when compared with their wild type counterparts in a folate-deficient environment (50% reduction; 37.6 ± 5.2 versus 18.3 ± 4.1, for wild type and β-pol+/− mice fed a folate-deficient diet, respectively, p < 0.01, Fig. 2B). It has been proposed that the size of the aberrant crypt per focus and the number of aberrant crypts per focus could be a more appropriate indicator of colon tumorigenesis. As shown in Fig. 2C, no significant differences in the number of aberrant crypts per focus were observed in all experimental groups treated with DMH. These data indicate that β-pol haploinsufficiency attenuates carcinogen-induced ACF development when folate is deficient.

FIGURE 3.

Impact of folate deficiency and DMH treatment on expression of β-pol in colon mucosa of β-pol+/− mice. A, analysis of β-pol mRNA levels in mucosa of wild type and β-pol haploinsufficient mice treated with DMH. Expression of the β-pol gene was determined using a real time PCR technique and the level was normalized based on Gapdh expression as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, analysis of β-pol protein levels in mucosa of wild type and β-pol haploinsufficient mice treated with DMH. The protein level was quantified using a Western blot analysis. Bars with different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.01. Bars indicate S.E.

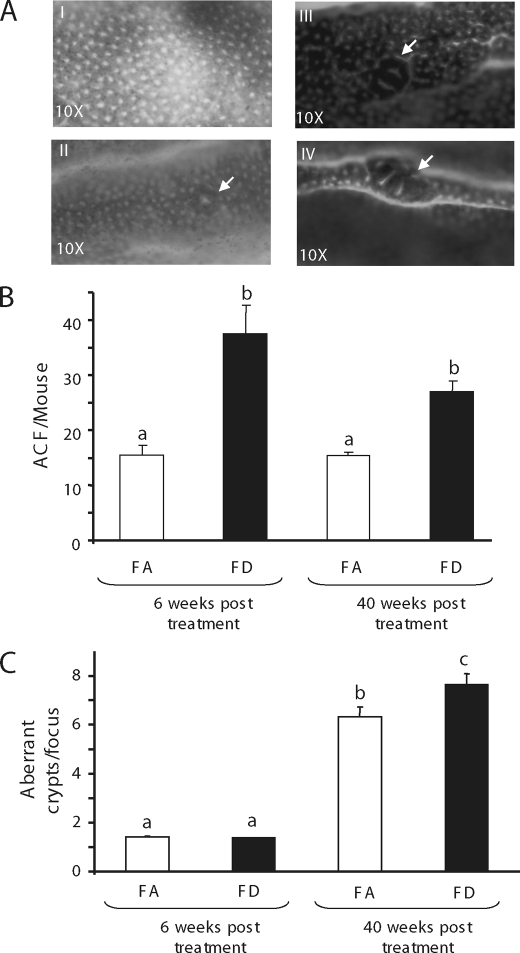

To determine whether prolonged folate deficiency increases ACF progression or results in ACF regression, wild type mice were maintained on their specific diets for 40 weeks post-DMH treatment. After sacrifice, colons were macroscopically examined for the development of ACF and the number of aberrant crypts per focus (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, as has been reported elsewhere, there was a lack of further increase in aberrant crypt focus numbers, but rather a regression of ACF as well as a further development to larger ACF with increased aberrant crypts per focus in these mice. Although we observed no significant change in crypt multiplicity at 6 weeks post-treatment for any group studied, the number of crypts per focus significantly increased in FD mice as compared with their FA counterparts after 40 weeks in wild type mice (7.63 ± 0.4 versus 6.33 ± 0.4, for FD and FA mice, respectively, p < 0.05). Moreover, ACF in FD mice displayed a well defined elevation above the surrounding mucosa compared with its FA counterpart, which appeared flat (Fig. 4A, panel IV). Thus based on the notion that the size of ACF and the number of aberrant crypts per focus are better indicators of tumor formation, folate deficiency does not only increase the number of ACF in response to DMH early on, but its adverse impact persists resulting in further development of aberrant foci and formation of microscopic adenoma, whereas this phenomenon could be hampered where β-pol is deficient. Accordingly, it was important to evaluate the experimental groups for tumor analysis. Determining tumor incidents in these mice is important as these data potentially shed light on the impact of BER deficiency on colon tumors in a folate-deficient environment, and determine potential continuity between ACF formation and development and metastasis of tumors.

FIGURE 4.

Impact of long term feeding on ACF formation and crypt multiplicity. Comparison of ACF formation and crypt multiplicity in mice fed either a FA or FD diet at 6 weeks versus 40 weeks post-DMH treatment. Panel A, I, normal colonic crypts; II, ACF formation in FD environment 6 weeks post-DMH; III, ACF formation in mice fed FA diet 40 weeks post DMH; and IV, number of ACF of mice fed a FD diet 40 weeks post-DMH treatment. Arrows depict the area of aberrant crypt formation. Panel B, relative number of ACF/mouse in mice fed either a FA or FD diet 6 or 40 weeks post-DMH treatment, respectively. Panel C, number of aberrant crypts per focus in mice fed either a FA or FD diet 6 or 40 weeks post-DMH treatment, respectively. Bars with different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. Bars indicate S.E.

Analysis of Pathology in β-pol Haploinsufficiency and Wild Type Counterparts in Response to Folate Deficiency and DMH Treatment

Having established the DMH induction of ACF in the colon of β-pol+/− mice and their wild type counterparts fed a FA and/or FD diet, we studied the impact of folate deficiency and DMH treatment on tumor formation in these animals, based on the known impact of DMH on colon and liver tissues. In this study, we followed animals for 40 weeks after the last DMH treatment to determine the incidence of tumor formation as outlined in Fig. 5A. Analysis of formalin-fixed and methylene blue-stained colons provided evidence of advanced ACF in the colon of wild type FD (Fig. 4, panel IV) mice treated with DMH as compared with FA mice (Fig. 4, panel III). In other words, whereas a more defined elevation above the surrounding mucosa was observed in ACF of FD fed mice, the FA mice displayed less developed ACF. Upon dissection of animals, we perceived gross changes in the pathology of the liver in FDWT DMH-treated mice (50% tumor formation) and FADMH-treated β-pol+/− (100% tumor formation). As shown in Fig. 5B, panels II and III, the architecture of the liver tissue in the FDWT and β-pol+/− fed a FA diet demonstrated an atypical morphology depicting progression of tumors. In contrast, there were no visible changes in the liver for wild type mice consuming a FA diet and β-pol+/− animals fed a FD diet. Taken together, FDWT and β-pol+/− fed a FA diet with DMH treatment show more developed ACF and tumor formation than FAWT DMH-treated and FD β-pol+/− animals. This is suggestive, yet again, of haploinsufficiency conferring protection when exposed to oxidative/alkylation stress induced by DMH treatment in a folate-deficient environment. Based on these data, it is inviting to suggest that β-pol haploinsufficiency in combination with folate deficiency might impact on cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to DMH, thus impacting on ACF development and consequent tumor formation. Accordingly, we wanted to determine the impact of β-pol haploinsufficiency and folate deficiency on gene expression in mucosal tissue of the colon.

FIGURE 5.

Impact of β-pol+/− and folate deficiency on induction of tumors in DMH-treated mice. A, feeding study was conducted as depicted in Fig. 2. The mice were sacrificed 40 weeks after the last treatment by CO2 asphyxiation and incidence of tumor progression was assessed. B, exemplary H&E micrographs showing tumor formation in liver sections from: (I) WT FA; (II) WT FD; (III) FA β-pol+/−; and (IV) FD β-pol+/− mice treated with DMH. The % value represents the percent of mice with visible liver tumor formation. All wild type animals fed the FD diet showed liver tumors through H&E analysis.

Effects of Folate Deficiency on Gene Expression in Colon Mucosal Cells

Having seen a difference in colon pathology, as aforementioned, we wanted to determine differential expression of genes in colon tissues of β-pol+/− mice subjected to DMH in a folate-deficient environment. To ascertain possible mechanisms of reduced ACF and tumor formation, we decided to conduct microarray analyses on FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated and FDWT DMH-treated colon mucosa, relative to FAWT. As depicted in the scatter plots of differentially expressed genes, there was a marked difference in expression of many genes in DMH-treated β-pol haploinsufficient mice subject to a folate-deficient environment (4621 up- regulated, 5757 down-regulated in FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated versus 528 up-regulated, 557 down-regulated in FD WT mice) (Fig. 6A). In other words, β-pol haploinsufficiency and DMH treatment resulted in more extensive differential expression of genes as compared with wild type untreated mice. To authenticate the outcome of microarray analysis, we performed quantitative RT-PCR using FullVelocityTM SYBR® Green qRT-PCR reagents (Stratagene) on select genes depicted as differentially expressed through microarray analysis. The selected gene products studied included Ung, N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase, β-pol, XRCC1, Ligase 3, and RAD51li. qRT-PCR results for the 6 genes selected were consistent with microarray data. All were significantly down-regulated in the FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated mice (p < 0.01) (supplemental Table S4). Having confirmed the validity of microarray findings, we wanted to identify the inter-relationships that existed between the abundance of differentially expressed genes.

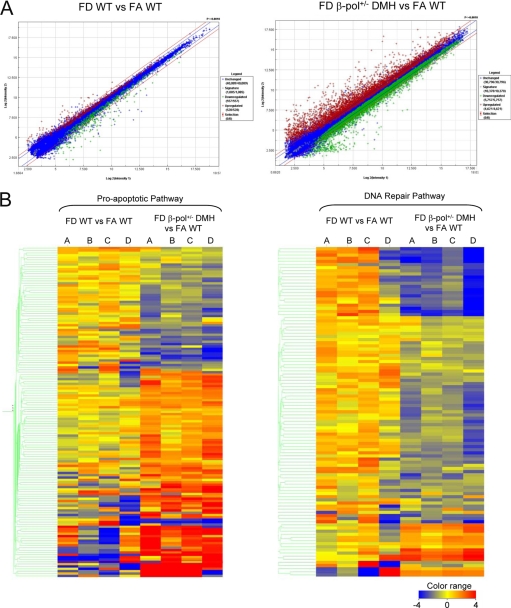

FIGURE 6.

Scatter plot of differentially expressed genes and heat map representation of microarray data for proapoptotic and DNA repair of differentially expressed genes. A, scatter plot of differentially expressed genes from colon mucosa from FD β-pol+/− relative to FA β-pol+/− tissues and WT FD relative to WT FA tissues included in the Agilent Whole Mouse Genome oligonucleotide microarray containing probes for over 41,000 well characterized genes. B, hierarchal clustering analysis was performed using GeneSpringGX V10 (Agilent Technologies) software, and the parameters were set for centroid linkage that calculates the euclidean distance between the respective centroids of two clusters. A heat map in quadruple (A–D) for each condition represents proapoptotic and DNA repair genes.

Based on our assessment of a possible role of DNA repair and apoptosis we used the DAVID biological function to determine the changes in individual gene expressions related to these two pathways. Once identified, we generated a series of hierarchal clustered heat maps based on the intensity of gene expression from raw data files (Fig. 6B). Hierarchal clustering assisted in exploring the relationships that exist among the statistical data identified in the microarray analysis. Here we show that upon conducting a clustered analysis, all the data demonstrate a thrust toward a reduction in DNA repair and an up-regulation in apoptotic related gene activity in the FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated mucosal tissue. In contrast, WT-untreated counterparts had a propensity toward either no difference in or slight up-regulation in DNA repair and a down-regulation in proapoptotic gene expression. Furthermore, FDWT DMH-treated groups showed either no difference or an up-regulation in DNA repair capacity and an up-regulation in apoptosis.

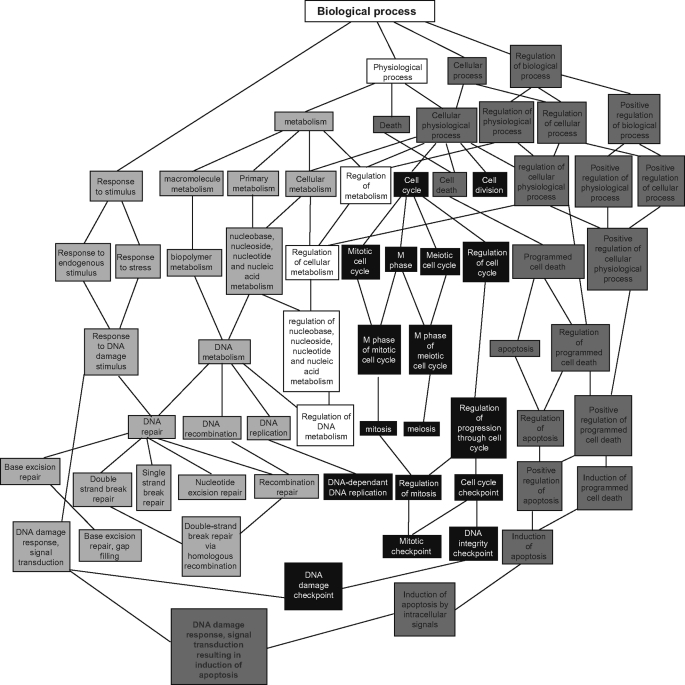

To further characterize the differences in gene expression, we input differentially expressed genes, from the raw data files, into directed acyclic graphs view of Gene ontology to acquire clusters of statistically (p < 0.01) enriched differentially expressed genes according to their gene ontology. In this analysis, all gene names from raw data files were input into GOTM without reference to significance or intensity levels. Here, again, even with limited data input, we confirmed enrichment in DNA repair response (Fig. 7, light gray boxes) and apoptotic activity (dark gray boxes) in DMH-treated FD β-pol+/−. As shown in Fig. 7, the ontology groups were enriched at the program cell death and apoptosis, as well as in BER, nucleotide excision repair, and recombination repair, all converging on DNA damage response, signal transduction, and induction of apoptosis.

FIGURE 7.

Directed acyclic graph view of gene ontology analysis of colonic mucosal tissue in FD β-pol+/−versus FA WT. Light gray boxes indicate enrichment of expression of genes related to DNA repair. Dark gray boxes indicate enrichment of expression of genes related to apoptosis.

Analyzing expression data with DAVID biological processes highlighted several genes related to apoptosis and DNA repair activity (supplemental Tables S2–S5). Interestingly, we observed a distinct decline in overall DNA repair activity, including but not exclusive to BER (Ung, Apex, and β-pol), mismatch repair (Msh2 and Msh3), and nucleotide excision repair (Ercc2 and Xpc). In contrast, there was an enhanced expression of several proapoptotic genes, including genes involved in intrinsic/extrinsic apoptotic pathways (Casp4 and Casp8), tumor necrosis factor signaling (Tnfsf12 and Tnfrsf26), as well as Gas1 and Trp63. All of these data suggest enhanced programmed cell death, based on enhanced apoptotic activity, forgoing DNA repair, or lack of response of DNA repair pathways to cellular damage, increasing the sensitivity of apoptotic related pathways. Interestingly, the differential expression of genes in the WT FD DMH-treated colonic mucosa was either not differentially expressed or up-regulated for DNA repair, with the exception of β-pol and up-regulated in apoptosis, apart from a down-regulation in Casp3. In addition, FD WT colonic mucosa were either not differentially expressed or for the most part, slightly up-regulated for DNA repair and showed reduction in apoptotic activity suggesting that in addition to folate deficiency, a compromised BER pathway is required to trigger apoptosis in DMH-treated mice. In view of these findings, we wanted to further confirm these results through a series of immunohistological experiments.

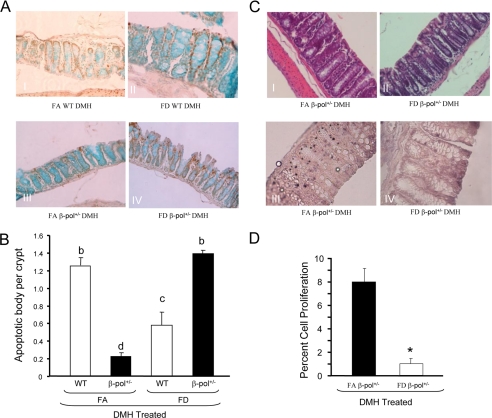

Evaluation of Apoptotic and Proliferative Activity in Colonic Mucosal Cells

Having determined the impact of β-pol haploinsufficiency on colon and liver tissue, we wanted to establish why BER insufficiency attenuates development of lesions in the face of deleterious surroundings of DMH-induced carcinogenesis and folate deficiency. We, therefore, conducted both apoptotic and proliferative assays because maintenance of mucosal integrity is reliant on the regulation of these two entities, i.e. development of ACF may arise if this integrity becomes compromised. To determine apoptotic activity in our experimental groups, we measured apoptosis in the colon using the TUNEL assay. First, folate deficiency increased apoptotic bodies in wild type animals (data not shown). Interestingly, folate deficiency induced a greater level of apoptotic activity in β-pol haploinsufficient mice as compared with wild type counterparts (Fig. 8A, panel IV). This confers with our previous data showing a significant increase in Casp3 activity in the liver of 2-nitropropane-treated FD BER-deficient mice as compared with FA counterparts, as measured by the Enzchek Casp3 Assay (19). Herein, we show a significant increase (20%) in Casp3 activity in FD β-pol+/− DMH-treated animals relative to FAWT DMH treatment (data not shown). These findings are indicative of increased apoptotic activity when dietary folate is deficient and BER is compromised. In addition, we ascertained a 35% increase in DNA single strand breaks in FD β-pol+/− with DMH treatment using DNA single strand breaks assay in comparison to FAWT DMH-treated mice using a Fast Micromethod DNA Single Strand Break assay (data not shown). Next, to characterize the effect of β-pol heterozygosity and folate deficiency on cell proliferation in response to DMH treatment, we examined the proliferative activity of colon tissues by examining BrdUrd incorporation. As shown in Fig. 8C, panel III, FA β-pol+/− mice showed significantly more proliferation (BrdUrd incorporation) as compared with FD β-pol+/− mice. Thus, the TUNEL and BrdUrd assays confirmed the differential expression observed in microarray analysis, suggesting that folate deficiency provides protection against tumorigenesis in DMH-treated β-pol+/− mice by altering the balance between DNA repair and apoptotic pathway favoring apoptosis.

FIGURE 8.

Impact of β-pol+/− and folate deficiency on apoptotic activity and induction of proliferation in colonocytes. A, representative photomicrographs showing TUNEL-positive staining in cells (brown) of colonic mucosa. I, WT FA; II, WT FD; III, FA β-pol+/−; and IV, FD β-pol+/− mice treated with DMH. B, tally of the TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells. WT and β-pol+/− were fed either a FA or FD diet and subjected to DMH treatment. Colon tissue was processed, TUNEL assay conducted, and the percent of apoptotic cells calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Means without a common letter differ, p < 0.01. Bars indicate S.E. C, representative photomicrographs showing H&E of colonic mucosa. I, FA β-pol+/−; and II, FD β-pol+/− mice treated with DMH. Representative micrographs showing BrdUrd staining (brown) of colonic mucosa. III, FA β-pol+/−; and IV, FD β-pol+/− mice treated with DMH. Proliferation analysis for β-pol haploinsufficient mice were treated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Briefly, 2 h prior to sacrifice mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdUrd (2.16 mg/kg body weight). Colon segments were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. BrdUrd incorporation was detected by immunostaining as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, enumeration of positive proliferation. Percent cell proliferation was conducted as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” Asterisk (*) indicates differences at p < 0.01. Bars indicate S.E.

DISCUSSION

In this study we examined the impact of BER deficiency on colon carcinogenesis in a mouse model. BER processes endogenous damage; as such, our interest has been in developing model systems to test the processing of endogenous damage and determine the impact of BER deficiency on tumorigenesis in vivo, specifically in the colon. First we display a significant decline in β-pol expression in the colon of the knock-out mice as compared with their wild type littermates, suggesting a BER deficiency in the colon of these mice. In addition, the β-pol+/− mice treated with DMH show a significant increase in ACF formation relative to wild type, substantiating the need for an intact BER process. We confirm that the β-pol heterozygous mice are predisposed to preneoplastic lesions and cancer development, primarily by reducing tolerance to DNA damage in response to the DNA damaging agent, DMH. As such, these manipulations gave rise to an animal model of colon carcinogenesis for future study.

Although the mechanism by which folate deficiency increases cancer risk is not clear, folate deficiency has been shown to induce damage repaired via the BER pathway (17). Branda et al. (10) have demonstrated that folate-deficient animals are less able to repair DNA damage induced by alkylating agents. For example, N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea was found to be more mutagenic within the context of folate deficiency. Interestingly, folate deficiency did not enhance the mutagenic effect of cyclophosphamide, suggesting a lack of sensitivity to lesions repaired by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Duthie et al. (4) have further shown that human colon epithelial cells grown in the absence of folate are poorly able to repair damages induced by methyl methanesulfonate and hydrogen peroxide. Growth in a low folate medium has also been shown to impair the excision repair capacity of colonocytes (32). More oxidative damage, which is repaired by BER, accumulates in response to amyloid β-peptide in neuronal cells depleted of folate (33). Based on our previous findings and these aforementioned studies, we were interested in determining what impact folate deficiency would have on a BER-deficient model. In this study, we confirm that a folate-deficient diet heightens the reduced DNA damage response when mice are subjected to a carcinogenic environment resultant in an increased in the number of ACF. We also show an increased incidence of microscopic adenoma and liver tumor formation in wild type mice upon DMH treatment when folate is deficient. These data indicate, in conjunction with our previous studies (17), that the pathway responsible for repairing these damages may be ineffective when folate is limiting. Based on the above findings, it is inviting to suggest that folate deficiency mimics BER deficiency perhaps by overwhelming the capacity of BER through inhibition of its rate-determining enzyme, DNA polymerase β.

Herein, folate deficiency in β-pol haploinsufficient mice demonstrated reduced development of ACF. In addition, prolonged feeding of the folate-deficient diet resulted in advanced ACF formation, microscopic adenoma, and liver tumors in wild type mice, whereas β-pol haploinsufficiency attenuated onset and progression of ACF to microscopic adenoma and prevented liver tumorgenesis. These findings are interesting because folate deficiency appears to provide protection against tumorigenesis in a BER-deficient environment in all tissues where DMH exerts its damage. Microarray data show (classification by gene ontology) a distinct down-regulation in DNA repair capacity including, but not restricted to BER, nucleotide excision repair, and mismatch repair, in FD β-pol+/− with DMH treatment.

Observing the lack of response of FD β-pol+/− in DNA repair, we studied the expression of apoptotic genes on our microarrays to determine whether cell death may be responsible for eliminating cells that had extensive damage thus reducing the level of ACF and tumor formation. Notably, there was an up-regulation of 75 differentially expressed genes related to apoptotic activity. There was an up-regulation in intrinsic/extrinsic apoptotic, and tumor necrosis factor signaling, as well as cell cycle arrest in β-pol haploinsufficient mice. Based on the results obtained through microarray and TUNEL analysis, we would suggest that colon cells in DMH-treated β-pol haploinsufficient mice in a folate-deficient environment would prefer to undergo cell death, rather than attempt repair. Interestingly, a distinct up-regulation in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase expression in FD DMH-treated β-pol haploinsufficient colonic mucosa is observed. In addition to mediating BER by recruiting BER intermediates like β-pol, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases are the key regulators of cell survival and death (34). Huang et al. (35) in their study utilizing Bax+/−Bak−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts, show depletion in ATP secondary to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation, which in turn inhibits Frap1, a mediator of cellular response to DNA damage. We suggest that down-regulation in expression of key enzymes in the BER pathway renders available poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases futile and are thus cleaved by Casp3 triggering apoptosis. Interestingly, whereas FDWT DMH-treated animals show a significant decline in the level of Casp3, a key “executioner” of apoptosis (36), it is up-regulated in β-pol haploinsufficiency. These findings provide further evidence of defense by BER deficiency in the multistep process of colon/liver cancer, when folate is deficient.

Our proposal that β-pol deficiency in a folate-deficient environment results in increased accumulation of DNA repair intermediates opting for cell death versus survival, reducing the onset and progression of preneoplastic lesions, is in agreement with findings by others. Ochs et al. (37) demonstrated that BER deficiency results in the accumulation of repair intermediates, along with increased DSB in β-pol null fibroblasts exposed to the alkylating agent, methyl methanesulfonate. Accumulation of DNA damage in these cells resulted in decline in Bcl-2 and increased apoptotic activity. Taverna et al. (38) have also shown that BER inhibition by methoxyamine increases cytotoxicity of the methylating agent temozolomide through persistence in AP sites, increasing DSB and apoptosis in HCT 116 colon cancer cell lines. Likewise, Rinne et al. (39) showed that overexpression of N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase in breast cancer cell lines and the exposure of these cell lines to alkylating agents significantly increased their sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic temozolomide. Sensitivity is further increased through co-administration of the BER inhibitor methoxyamine making cells unable to complete repair initiated by the glycosylase, and resulting in an increase in the number of AP sites and single strand DNA-binding proteins. Fishel et al. (40) have shown that overexpression of N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase, in addition to inhibition of the BER pathway via methoxyamine, dramatically increases the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to the DNA methylating agent temozolomide via an increase in apoptotic activity. In other words, inhibition of the BER pathway by methoxyamine downstream of glycosylase resulted in an accumulation of DNA repair intermediates, and increased DNA DSBs, triggering apoptosis. Furthermore, Trivedi et al. (41) showed that elevated N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase expression in addition to β-pol knockdown would result in increased sensitivity of human breast cancer cells to temozolomide. Additionally, they also (41) showed that overexpression of β-pol with mutation in its polymerase site, although maintaining its deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity, resulted in restoration of resistance to temozolomide in β-pol knockdown human breast cancer cell lines. The in vitro studies outlined above utilize specific glycosylases for the creation and persistence of abasic sites, whereas methoxyamine potentiates the cytotoxicity of temozolomide through its binding to abasic sites, hampering BER, resulting in accumulation of repair intermediates and ultimately, DNA DSBs. These conditions generate a perfect environment for apoptosis to take place. We find the results of these studies intriguing, for the aforementioned were conducted within cell lines, whereas our in vivo data demonstrate protection against actual onset and progression of tumors, via similar mechanisms.

In line with our findings, Lawrance et al. (42) showed that folate deficiency in mthfr-deficient Apcmin/+ mice results in elevation of the dUTP/dTTP ratio in DNA, increasing apoptotic activity with a reduction in adenoma formation in colon tissue. Interestingly, Apc has been shown to interact with β-pol (43). Furthermore, haploinsufficiency in the reduced-folate carrier gene (Rfc+/−), which creates a folate deficiency phenotype, resulted in decreased adenomas and tumor load in Apcmin/+ mice. In addition, Branda et al. (44) showed that folate deficiency reduced mutation frequency in 3-methyladenine glycosylase null mice exposed to methyl methanesulfonate. The aforementioned demonstrate much the same as our investigation in that modulating BER repair, through β-pol and exposure to folate deficiency, results in reduced repair activity while influencing apoptosis. Additional research conducted by Duthie et al. (45) demonstrated that NCM460 immortalized cells in folate-deficient medium exposed to hydrogen peroxide exhibit increased apoptotic activity, as well as decreased proliferation. Furthermore, Crott et al. (46) showed an inverse correlation between expression of genes involved in the cell cycle checkpoint and medium folate levels (25 to 100 nm) in NCM460, HCEC, and NCM356 cell lines derived from human colon, irrespective of oxidative stress. These studies, much like our own, have significantly reduced levels of folate, rather than a complete folate depletion. In our experiments, despite use of a folate-deficient diet and use of succinyl sulfathiazole, an 80–90% reduction in serum folate levels is observed relative to folate-adequate diets. It is at this reduced level that we see protective effects. This study has great therapeutic importance and human relevance as recent findings indicate BER inhibitors in combination with the DNA methylating agent temozolomide function as an effective chemopreventive agent in colon cancer (23). In addition, these findings have relevant translational implications, because variants/polymorphisms in BER have been associated with increased cancer risk, and an alteration in micronutrients could potentially provide protection under the right conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Richard Caldwell from the Journal of the American College of Nutrition for critical review of the manuscript. Microarray data analysis was supported by the Microarray and Bioinformatics Facility Core, Wayne State University, supported by National Institutes of Health NIEHS Center Grant P30 ES06639.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA121298 (to A. R. H.). This work was also supported by American Institute for Cancer Research Grant 03A061 (to A. R. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S5 and Excel data.

- BER

- base excision repair

- β-pol

- DNA polymerase β

- FD

- folate deficient

- FA

- folate adequate

- WT

- wild type

- DMH

- 1,2-dimethylhydrazine

- ACF

- aberrant crypt foci

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcription

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling

- BrdUrd

- 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine

- DSB

- double strand break.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duthie S. J., Hawdon A. (1998) FASEB J. 12, 1491–1497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnyk S., Pogribna M., Miller B. J., Basnakian A. G., Pogribny I. P., James S. J. (1999) Cancer Lett. 146, 35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duthie S. J., Grant G., Narayanan S. (2000) Br. J. Cancer 83, 1532–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duthie S. J., Narayanan S., Blum S., Pirie L., Brand G. M. (2000) Nutr. Cancer 37, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y. I., Shirwadkar S., Choi S. W., Puchyr M., Wang Y., Mason J. B. (2000) Gastroenterology 119, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacGregor J. T., Wehr C. M., Hiatt R. A., Peters B., Tucker J. D., Langlois R. G., Jacob R. A., Jensen R. H., Yager J. W., Shigenaga M. K., Frei B., Eynon B. P., Ames B. N. (1997) Mutat. Res. 377, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everson R. B., Wehr C. M., Erexson G. L., MacGregor J. T. (1988) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 80, 525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Libbus B. L., Borman L. S., Ventrone C. H., Branda R. F. (1990) Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 46, 231–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duthie S. J., Narayanan S., Brand G. M., Pirie L., Grant G. (2002) J. Nutr. 132, Suppl. 8, 2444S–2449S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branda R. F., Hacker M., Lafayette A., Nigels E., Sullivan L., Nicklas J. A., O'Neill J. P. (1998) Environ. Mol. Mutagen 32, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branda R. F., Lafayette A. R., O'Neill J. P., Nicklas J. A. (1999) Mutat. Res. 427, 79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmquist G. P. (1998) Mutat. Res. 400, 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindahl T. (2000) Mutat. Res. 462, 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava D. K., Berg B. J., Prasad R., Molina J. T., Beard W. A., Tomkinson A. E., Wilson S. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21203–21209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabelof D. C., Guo Z., Raffoul J. J., Sobol R. W., Wilson S. H., Richardson A., Heydari A. R. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 5799–5807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabelof D. C., Ikeno Y., Nyska A., Busuttil R. A., Anyangwe N., Vijg J., Matherly L. H., Tucker J. D., Wilson S. H., Richardson A., Heydari A. R. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 7460–7465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabelof D. C., Raffoul J. J., Nakamura J., Kapoor D., Abdalla H., Heydari A. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36504–36513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu H., Marth J. D., Orban P. C., Mossmann H., Rajewsky K. (1994) Science 265, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unnikrishnan A., Raffoul J. J., Patel H. V., Prychitko T. M., Anyangwe N., Meira L. B., Friedberg E. C., Cabelof D. C., Heydari A. R. (2009) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 1488–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu H., Cabrera R. M., Wlodarczyk B. J., Bozinov D., Wang D., Schwartz R. J., Finnell R. H. (2007) BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B., Schmoyer D., Kirov S., Snoddy J. (2004) BMC Bioinformatics 5, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokal R. R., Rohlf F. J. (1981) Biometry, pp. 169–176, W. H. Freeman and Co., New York [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miknyoczki S., Chang H., Grobelny J., Pritchard S., Worrell C., McGann N., Ator M., Husten J., Deibold J., Hudkins R., Zulli A., Parchment R., Ruggeri B. (2007) Mol. Cancer Ther. 6, 2290–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bird R. P. (1995) Cancer Lett. 93, 55–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLellan E. A., Medline A., Bird R. P. (1991) Cancer Res. 51, 5270–5274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenoglio-Preiser C. M., Noffsinger A. (1999) Toxicol. Pathol. 27, 632–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.No H., Kwon H., Park Y., Cheon C., Park J., Park T., Aruoma O., Sung M. (2007) Nutr. Res. 27, 659–664 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y. I., Christman J. K., Fleet J. C., Cravo M. L., Salomon R. N., Smith D., Ordovas J., Selhub J., Mason J. B. (1995) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 1083–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapkin R. S., Kamen B. A., Callaway E. S., Davidson L. A., George N. I., Wang N., Lupton J. R., Finnell R. H. (2009) J. Nutr. Biochem. 20, 649–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cravo M. L., Mason J. B., Dayal Y., Hutchinson M., Smith D., Selhub J., Rosenberg I. H. (1992) Cancer Res. 52, 5002–5006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y. I., Salomon R. N., Graeme-Cook F., Choi S. W., Smith D. E., Dallal G. E., Mason J. B. (1996) Gut 39, 732–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi S. W., Kim Y. I., Weitzel J. N., Mason J. B. (1998) Gut 43, 93–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruman I. I., Kumaravel T. S., Lohani A., Pedersen W. A., Cutler R. G., Kruman Y., Haughey N., Lee J., Evans M., Mattson M. P. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 1752–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peralta-Leal A., Rodríguez-Vargas J. M., Aguilar-Quesada R., Rodríguez M. I., Linares J. L., de Almodóvar M. R., Oliver F. J. (2009) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Q., Wu Y. T., Tan H. L., Ong C. N., Shen H. M. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 264–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson Q. P., Goode D. R., West D. C., Ramsey K. N., Lee J. J., Hergenrother P. J. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 388, 144–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochs K., Lips J., Profittlich S., Kaina B. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 1524–1530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taverna P., Liu L., Hwang H. S., Hanson A. J., Kinsella T. J., Gerson S. L. (2001) Mutat. Res. 485, 269–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rinne M., Caldwell D., Kelley M. R. (2004) Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 955–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fishel M. L., He Y., Smith M. L., Kelley M. R. (2007) Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trivedi R. N., Wang X. H., Jelezcova E., Goellner E. M., Tang J. B., Sobol R. W. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 505–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrance A. K., Deng L., Rozen R. (2009) Gut 58, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaiswal A. S., Narayan S. (2008) Cancer Lett. 271, 272–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Branda R. F., O'Neill J. P., Brooks E. M., Powden C., Naud S. J., Nicklas J. A. (2007) Mutat. Res. 615, 12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duthie S. J., Mavrommatis Y., Rucklidge G., Reid M., Duncan G., Moyer M. P., Pirie L. P., Bestwick C. S. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 3254–3266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crott J. W., Liu Z., Keyes M. K., Choi S. W., Jang H., Moyer M. P., Mason J. B. (2008) J. Nutr. Biochem. 19, 328–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.