Gaston Labat recognized that scientific knowledge was a key to successful regional anesthesia. He emphasized anatomic preparation, stating “A thorough knowledge of descriptive and topographic anatomy…is a condition which anyone desirous of attempting the study of regional anesthesia should fulfill.”1 During his career, which constituted the first four decades of the previous century, anatomic science was not only the core topic for a regional anesthetist's study, but was essentially all the science there was relevant to the topic. Since this is no longer the case, this review offers observations on the anatomy and function of the primary sensory neuron (PSN), the most important cell in regional anesthesia.

Where the primary sensory neuron is

In order to convey sensory information from the periphery to the CNS, PSNs span from their receptive fields to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This length, which in some cases reaches more than 1.5m, makes them the largest cells in the body. Not only does this provide multiple opportunities for anesthetization along their course, but it also exposes them to injury. Their design is pseudounipolar, meaning that a single axon emerges from the soma (cell body) that divides such that one branch travels to the periphery and the other to the spinal cord. This puts the soma out of the way, off on a sidetrack (the T-branch), which allows the rapid transit of action potentials (APs) that aren't slowed by having to pass through an intervening soma.

Dorsal roots within the subarachnoid space carry the central axons of PSNs. There is a great range of dorsal root diameters.2 Those in the distal cauda equina that innervate the perineum are at greatest risk of local anesthetic toxicity due to their very small diameter, and their passage through the caudal-most dural sac where undiluted hyperbaric local anesthetic may accumulate. The fibers of the dorsal roots are minimally protected from needles inserted during spinal anesthesia, since the pia covering them is insubstantial. Nonetheless, nerve root damage from needle trauma or local anesthetic toxicity at the point of spinal anesthetic injection is essentially unknown. This is probably due to the mobility of the roots, allowing them to slide away from needles. Furthermore, the very porous nature of the pia that surrounds the fibers of the roots permits the ready dissipation of local anesthetic after a chance injection into a root, so that toxic concentrations are not trapped in the immediate vicinity of the PSN fibers.

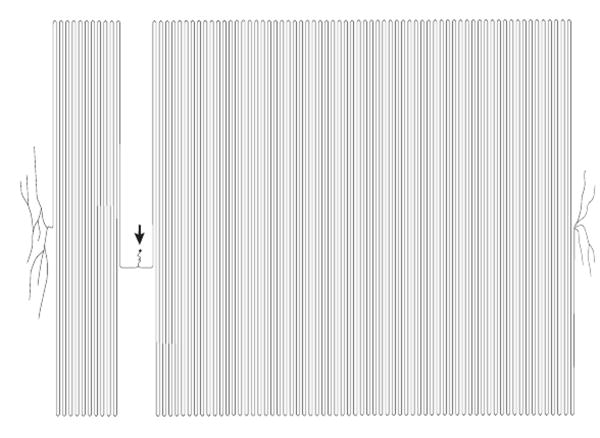

The peripheral nerves of the trunk and limbs originate as the spinal nerves, which receive the peripheral branch of the PSNs. Immediately outside of the intervertebral foramen, a miniature plexus rearranges motor and sensory fascicles into the posterior and anterior primary rami of the spinal nerve at each level (Fig. 1).3 The small diameter of these fascicles provides a site for highly efficient local anesthetic action in the perivertebral space, for instance after a selective spinal nerve injection or epidural anesthesia.

Figure 1.

Sequential cryomicrotome sections of the adult human intervertebral foramen between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae, demonstrating the structure of the proximal spinal nerve. The specimen was injected with orange ink by an epidural approach prior to freezing and sectioning. The orange dot (arrowhead) is an ink-filled drill hole used for guiding alignment. Medial is left in the image, anterior is up; the scale bar is common to all panels. A. At the level of the pedicle, the ventral root (vr) and dorsal root (dr) have diverged from the thecal sac in a common dural sleeve and are apposed to the medial aspect of the pedicle. The ventral primary rami (vpr) of the next rostral level are seen entering the substance of the psoas muscle. B. Somewhat more caudal, at the level of the intervertebral foramen, the ventral root and dorsal root ganglion (drg) are well outside the spinal canal, where injectate has followed. A ramus communicans (rc) is traveling posteriorly from the paravertebral sympathetic chain (off the anterior edge of the image). C. At a more caudal level, even with the rostral margin of the intervertebral disc, the dorsal root ganglion has split into fascicles that merge with similar components from the ventral root and ramus communicans to form a small plexus, composing the initial fascicles of the spinal nerve (snf). D. At a somewhat more caudal level, even with the rostral end of the intervertebral foramen, the fascicles merge into the ventral and dorsal primary rami of the spinal nerve (vpr, dpr).

The dorsal root ganglion (DRG), which is interposed between the dorsal root and the spinal nerve, is a very special organ that resides in a very dangerous place. One hazard is its proximity to the zygapophyseal (facet) joints, as well as to the intervertebral disc (Fig. 2). Arthritis of the former and herniation of material from the latter are the most common cause of radiculopathy (Fig 3). A further hazard is iatrogenic. The DRG is often punctured by needles during selective spinal nerve blocks (foraminal injections), and anesthetic or steroid solutions are commonly injected within it.4 However, this seems to be extraordinarily well tolerated, with rare evidence of damage. The cervical level is a very important exception to the innocuous nature of intra-ganglionic injection, due to the very short path length from the DRG to the spinal cord (Fig. 4), where arrival of injected material may produce disastrous cord damage.

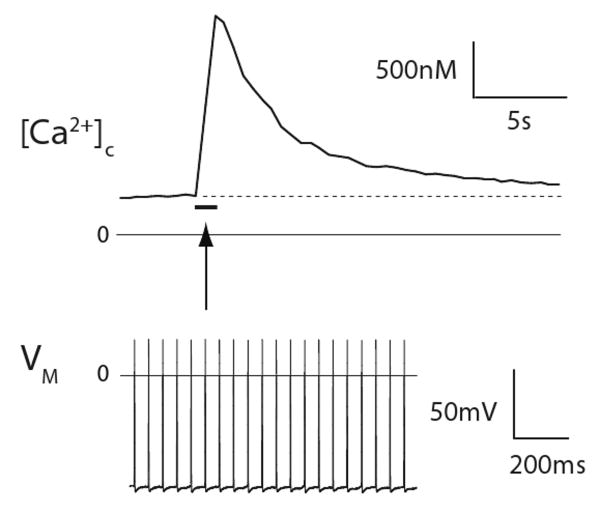

Figure 2.

Digital reconstruction of human cryomicrotome axial images (using Skandha, copyright by the Department of Biologic Structures, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington), demonstrating the normal anatomy of the spinal canal and intervertebral foramen. A. Looking caudally from the plane of the 3rd lumbar vertebral pedicles, the medial apertures of the left L3/4 and L4/5 are apparent where they branch off from the vertebral canal. Bone is white/blue, fat is red, ligamentum flavum is yellow, the venous system is dark blue, and the disc and posterior longitudinal ligament are brown. Empty spaces would be occupied by the thecal sac in the spinal canal and the nerve root sleeve in the intervertebral foramen. Abundant fat is present in the “axilla” area between the main dural sac and the diverging nerve root sleeve. B. A more oblique view of the same digitized specimen, with the fat removed to show the structures that may impinge on nerve tissue. The dorsal root ganglion and ventral root (shown in dotted orange outline) are in the rostral end of the foramen clear of the disc, but may be compressed if loss of disc height decreases the rostro-caudal dimension of the foramen. The most common location of disc herniation is parasagittal (arrow), which most often affects the nerve roots that are heading for their exit at the next lower foramen.

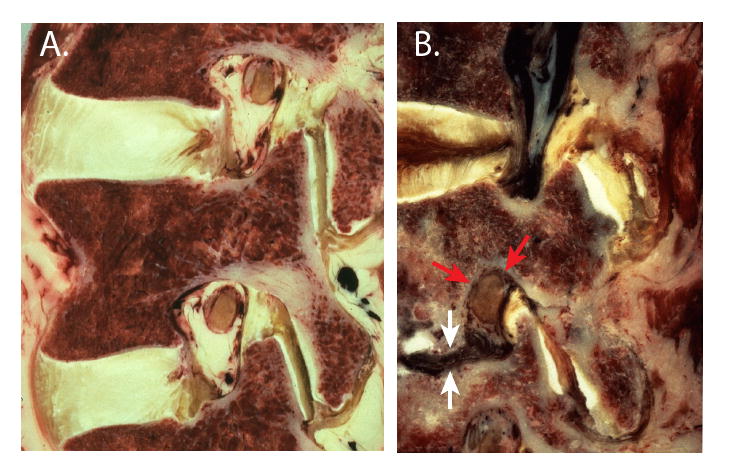

Figure 3.

Anatomy of the intervertebral foramen in human paramedian sagittal cryomicrotome sections. A. The L3/4 and L4/5 foramina in a normal specimen are the shape of an inverted teardrop. At this lateral plane, the dorsal root ganglion is apposed to the pedicle and the ligamentum flavum. B. Disc collapse (white arrows) results in compression of the dorsal root ganglion (red arrows) through the combined effects of entry of extruded disc material (dark) into the inferior portion of the foramen, rostro-caudal shortening of the foramen, and buckling of the ligamentum flavum forward against the ganglion.

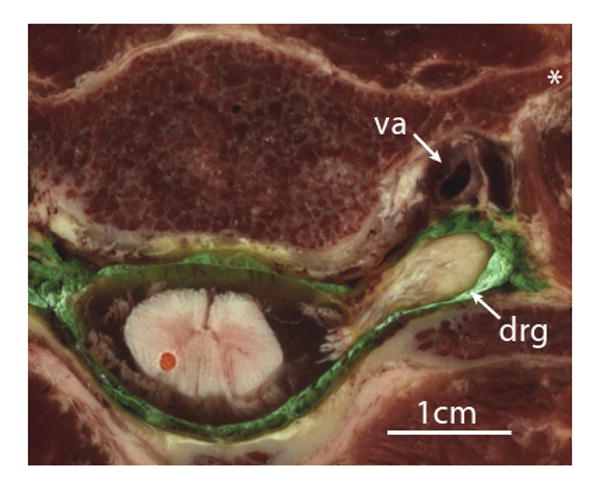

Figure 4.

Axial cryomicrotome section through the C5/6 intervertebral foramen in a human specimen injected with green ink by an epidural approach prior to freezing and sectioning. The dorsal root ganglion (drg) lies outside the intervertebral foramen, posterior to the vertebral artery (va). The apparent discontinuity of the roots with the spinal cord is due to their sloping course that takes them out of the plane of the image. Injection into the ganglion would readily convey even a small volume of injected solution into the cord. Also shown is the anterior tubercle of the transverse process (*).

A fascinating feature of the DRG is its lack of the barriers that elsewhere in the central and peripheral nervous system constrain entry of substances from the circulation (Fig. 5). A teleological explanation for this has proved elusive. The few areas of the CNS that share this feature serve a sensing function, such as the area postrema in the brain that controls vomiting, but a purpose for exposing PSN somata to signaling mediators in the circulation is unknown.5 The myalgias and arthralgias that accompany systemic infection may, however, be a manifestation of the action of circulating inflammatory mediators upon the PSNs. Another consequence of the lack of a blood-DRG barrier is deposition of intravenous therapeutic drugs such as anti-neoplastic drugs (e.g. cisplatin, paclitaxel) and anti-retroviral agents, which thereby produce treatment-limiting peripheral neuropathy that is selective for sensory neurons in the DRG.6

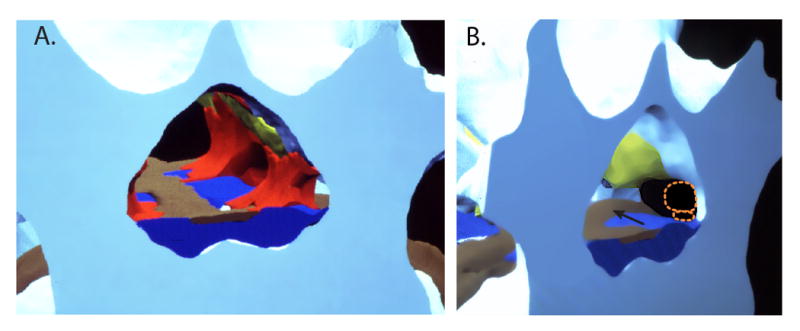

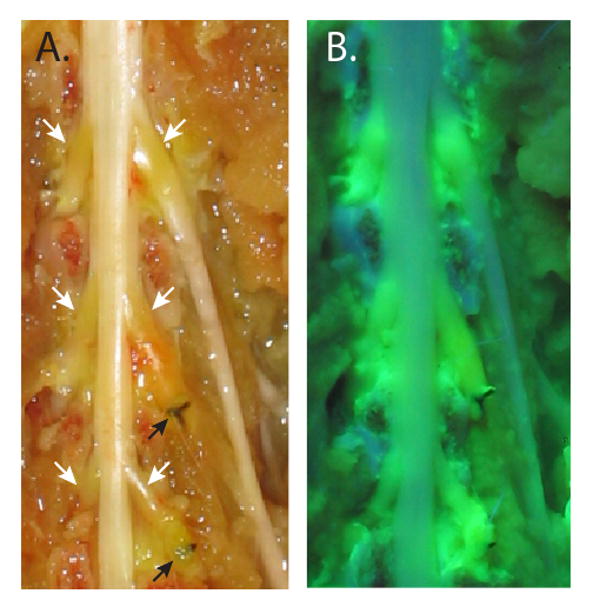

Figure 5.

The dorsal aspect of the rat dural sac and spinal nerves, exposed by the removal of the vertebral arches, following intravenous injection of fluorescein. A. Normal illumination shows fluorescein accumulation (orange discoloration) in the areas of the dorsal root ganglia (white arrows) but not in normal nerves and cord. Ligatures on the L5 and L6 spinal nerves (black arrows) are from prior surgical preparation of the spinal nerve ligation neuropathic pain model. B. Ultraviolet illumination shows extravasated fluorescein within the dorsal root ganglia, and in spinal nerve segments just proximal to the ligatures, but not in other neural tissue.

The DRG likewise lacks a protective surrounding capsular membrane,7 unlike the perineurium that defines the peripheral nerve fascicles and regulates their internal milieu. The high permeability of the DRG capsule means that this organ is preferentially imbued with agents injected into the epidural space or intervertebral foramen. This fortuitous property may underlie the efficacy of injected steroids when used for treating neuropathic pain, which may directly address pain pathogenesis attributable to inflammatory mediators released by activated DRG glial cells. Furthermore, the ready entry of local anesthetics into the DRG may account for the segmental nature of epidural anesthesia. The permeable nature of the DRG membrane may also explain the relative tolerance of this site to intraneuronal local anesthetic injection,4 since toxic concentrations of local anesthetic are not trapped within the DRG. The very high density of blood capillaries8 may additionally explain the relative hardiness of the DRG compared to the easily damaged CNS and peripheral nerves.

The very talented sensory neuron soma

The DRG is the site where the PSN somata reside, comprising a population of perhaps 15,000 neurons per DRG at segmental levels where the major plexuses innervate the limbs. Because of the very great length of the PSN axons and the relatively small size of their somata (20-50μm diameter), it can be calculated that only about 0.2% of the cytoplasm of a PSN is located in the soma, whereas 99.8% is found in the axon (Fig. 6).4 Since proteins and even mitochondria are manufactured in the soma, the metabolic demands upon them are very high, and the great distances required for axoplasmic transport to supply the distant axons predisposes these fibers the earliest to damage by metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus.

Figure 6.

A representation of the proportionate sizes of the primary sensory neuron that would innervate the foot of an adult human, showing the soma (arrow) and central and peripheral axons (left and right). The sizes are scaled to a 50μm soma diameter, 5μm axonal diameter, and axon lengths of 30cm and 120cm. (Based on ref. 5, by permission.)

In order for their nerve endings to respond to the various environmental stimuli that trigger peripheral sensation, the PSN somata produce a wide variety of the peptide receptors sensitive to mechanical deformation, chemical signals, heat and cold. Likewise, the machinery and neurotransmitters for synaptic communication at the central terminals in the CNS must also be provided. These critical elements are transported to their peripheral and central targets, but a residue remains in the somatic cytoplasm and membrane, allowing assessment of their function in individual neuronal somata. Examination of PSN somata has been the core research model that has explained sensory neuron function on a cellular and molecular level, including sensory transduction, patterns of excitability, and expression of neurotransmitters and receptors. Among the neurons of each DRG, there exist a high degree of specialization, consisting of neuronal subgroups that are categorized by sensory modality (heat, cold, mechanical, chemical), sensory intensity (responsiveness to low intensity stimuli versus those that require noxious, high intensity stimulation to initiate firing), conduction velocity (rapidly conducting myelinated fibers versus axons that are bare and slow), and neurotransmitter release (only amino-acid neurotransmitters versus peptidergic neurons that also release pain-mediating transmitters such as substance P). Thus, in contrast to the concept of a few decades ago, PSNs are a highly diverse population with specialized sensory roles.

Although they are functionally exposed to the body's general internal milieu without a selective barrier, the PSN somata are nonetheless coddled by a layer of support cells, the satellite glial cells (Fig. 7). Together, 8 or so of these epithelial-like cells completely encircle the neuronal soma, insulating it electrically from adjacent neurons and regulating the neuron's microenvironment. These glia are not inert elements however, since they communicate chemically with the neuron with which they form a functional unit.9 Following injury or inflammation of a peripheral nerve, its DRG shows dramatic proliferation of the satellite glial cells, with thickened layers encircling the DRG somata.10 Production of cytokines by these activated glial cells is an important contributor to the chronic pain that follows peripheral nerve injury.

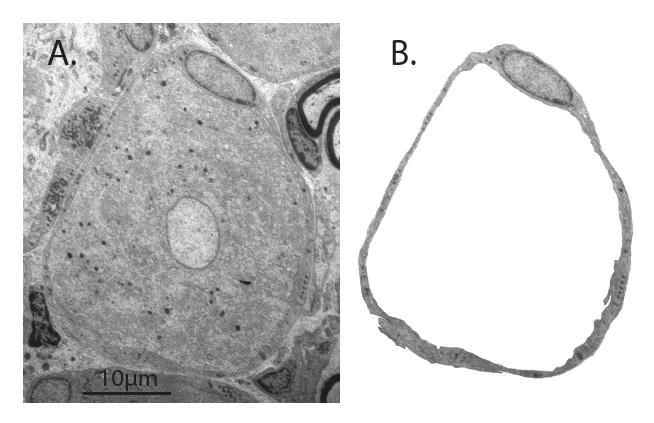

Figure 7.

Electron microscopy image of rat dorsal root ganglion. A. The center of the image shows the soma of a sensory neuron of the small-dark category. B. An envelope of satellite glial cells, including the nucleus of one, surrounds the neuronal soma (removed from the image).

What the primary sensory neuron does

The principal role of the PSN is to conduct APs from the sensory receptive field to central terminals for neurotransmission in the CNS, whereby sensations are generated. There is growing recognition, however, that AP traffic may go in the reverse direction as well. These impulses release peptides that result in vascular leakage and sensitization of other sensory fibers. This process, known as neurogenic inflammation, may contribute to the generation conditions as diverse as asthma, fibromyalgia, eczema, and migraine.

In humans, evaluation of afferent PSN function is relatively straightforward, since the subject can report the intensity and nature of the sensation associated with various stimuli. In animal subjects, however, this becomes a fundamental problem. For instance, pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience…”11 So how can we query a rat whose foot we heat or poke? The standard approach is to identify the threshold intensity that elicits a withdrawal reaction, and then equate a decreased threshold with pain. There are numerous uncertainties with this assumption, however,12,13 and validation is only occasionally pursued. For this reason, as well as the inevitable various differences between species, it is safest to consider pain research in animals as a means to generate hypotheses, not to test them.

The cellular event that serves the SFN's core responsibility of conveying sensory information is the generation of an AP at the its peripheral end in response to a stimulus, and its propagation along the length of the axon to the central terminal. This is conceptually simple: “Sensory neurons are designed to speak only when spoken to and to do what they are told” (Robert LaMotte PhD, Department of Anesthesiology, Yale). But this statement belies the complex challenge faced by a cell that must maintain its membrane in a state of excitability that is tuned to be neither insufficiently excitable, whereby sensation fails, nor excessively excitable, whereby inappropriate sensations are experienced in the absence of relevant stimuli. It is easy to disrupt this balance, as a large variety of diseases show. The main motive for understanding the function of the PSN is to prevent or correct these imbalances.

Firing APs requires an excitable membrane equipped with channels that can conduct selected ionic currents in a sequence that is dictated by the transmembrane potential and time. The AP is initiated by an inward Na+ current that promptly turns itself off (inactivates), but not until the resulting depolarization triggers inward Ca2+ current, as well as the outward K+ current that repolarizes the membrane to terminate the AP. Voltage-gated Ca2+ fluxes are particularly important since Ca2+ ions not only carry a depolarizing charge, but additionally act as second messenger. The elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ regulates all the critical neuronal functions, including development, excitability, neurotransmitter release, gene expression, and apoptosis (programmed cell death).

The importance of sensory neuron calcium

Flow of Ca2+ through the sensory neuron membrane can best be studied using dissociated somata and the electrophysiological technique of patch-clamp recording. This shows that injury of the peripheral axon is followed by loss of inward Ca2+ current,14,15 which is contrary to what might be expected from the intrathecal use of Ca2+ channel blockers for analgesia. However, the analgesic effect of Ca2+ channel blockers administered into the CNS is due to interruption of neurotransmitter release in the dorsal horn. At peripheral sites, such as in DRG somata, loss of Ca2+ influx has the predominant effect of limiting outward K+ current, due to the dependence of an important subset of K+ channels upon Ca2+ for activation. These Ca2+-activated K+ currents generate the afterhyperpolarization that follows the AP, which is the brake that restrains repetitive firing. Thus, loss of Ca2+ influx leads to hyperexcitability of the PSN.16 A further Ca2+ dependent PSN process is the natural filtering of high frequency traffic that happens where the peripheral and central axons meet at the T-branch, due to the process of impedance mismatch.17 Injury-related loss of Ca2+ current permits higher frequency bursts to pass this point and travel on to the CNS. Many injury-related processes other than Ca2+ current loss can disrupt neuronal behavior and initiate ectopic activity or hypersensitivity to stimulation. However, the Ca2+ regulation of excitability overlays these other processes and modulates the firing patterns of the injury-induced activity regardless of the initiating factors.

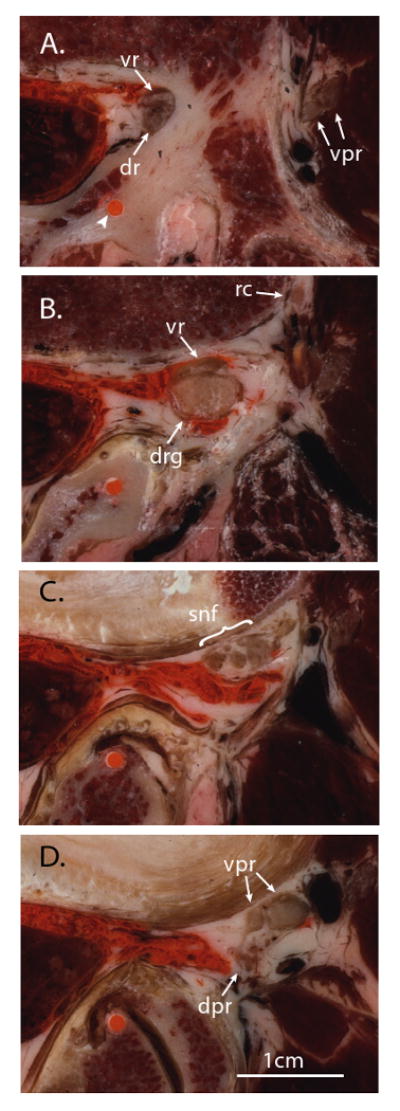

Calcium entry through the membrane is just the beginning of the Ca2+ signaling story. The Ca2+ that enters produces a period of elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration that is termed the Ca2+ transient. Even single or brief series of APs result in the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ that remains elevated for many seconds to minutes, compared to the few millisecond duration of an AP (Fig. 8). This integrative function can be considered a form of memory, by which the PSN alters its function on the basis of its immediately preceding experience.

Figure 8.

Primary sensory neuron memory, in the form of a sustained cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) signal. A 1 second train of 20 action potentials, each lasting approximately 1 millisecond (shown in the lower panel, and represented by the bar in the upper panel), produces a prolonged, 5-fold elevation of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ level (upper panel). Recordings were made simultaneously from a neuronal soma in an intact dorsal root ganglion, activated by action potentials conducted from axonal stimulation in the attached dorsal root. Dotted line in the upper panel represents resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ level. VM, transmembrane potential.

Like other cell types, PSNs sequester Ca2+ in stores residing inside intracellular organelles, predominantly the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This provides a means to buffer high Ca2+ levels by sequestration into the ER when cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels are high. The stored Ca2+ can also be released to amplify the Ca2+ transient initiated by Ca2+ entry from outside the neuron. The channels that release Ca2+ from the stores (the ryanodine receptors) are sensitive to cytoplasmic Ca2+, such that Ca2+ entry into the cell also triggers release of the stored Ca2+, which constitutes the phenomenon called Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). Injury of the peripheral axon depletes the Ca2+ stores, both by decreasing the size of the ER and by decreasing the concentration of Ca2+ within the ER.18,19 This has the effect of limiting the stored Ca2+ available for release during neuronal activation. Since the Ca2+ released by CICR is particularly important in activating K+ channels, the result is exacerbation of neuronal hyperexcitability.18 Depletion of Ca2+ within the ER also impedes proper folding of newly minted proteins, which inhibits overall protein synthesis.

Calcium stores may be released under pathological situations. For instance, mutations in the ryanodine receptor isoform expressed in skeletal muscle underlies malignant hyperthermia. Local anesthetics are known to activate the ryanodine receptors and release Ca2+.20 It is likely that a critical factor causing damage to neurons in the cauda equina during spinal anesthesia with lidocaine is release of the stored Ca2+ by high lidocaine concentrations due to poor mixing in the CSF.

The primary sensory neuron as a target of therapy

Basic research has produced a deluge of putative pathophysiologic mechanisms to account for PSN dysfunction, especially pain. However, none of this has resulted in a usable new treatment for pain. Ziconotide, also known as SNX-111 and Prialt, might be considered an exception. However, the requirement for continuous intrathecal administration, and the 31% incidence of severe complications even with brief treatment,21 make this a problematic therapy. A major impediment to treating PSN disease with systemic or CNS-applied drugs is that correcting the underactivity or overactivity of the misbehaving PSN neurons is impossible without affecting the same channels that play necessary roles in healthy neurons. This is a result of the limited set of molecular machinery that neurons have to perform their various functions. It will be unlikely that ablation of the activity of any channel or receptor, no matter how specific the blocker, will have an acceptable benefit versus side effect profile when given systemically or throughout the central nervous system, such as with intrathecal delivery.

Anatomic targeting of treatment provides an alternative to wide distribution of therapeutic agents that can address the need for selective action. The DRG is an appealing organ for drug application due to its permeable capsule and its tolerance to injection. Since many PSN diseases are local rather than systemic (e.g. trauma, cancer, zoster, radiculopathy), treatment may be anatomically restricted to a few DRGs. Techniques are not available for sustained infusions at a single DRG. However, molecular therapy is developing rapidly, and gene delivery using viral vectors may allow sustained manipulation of specific signaling pathways in the PSN upon genetic transduction of its soma. Such an approach may provide adequate specificity to capitalize on the new knowledge of PSN function in painful conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by grant NS-42150 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia, May 2, 2009, Phoenix

References

- 1.Labat G. Regional Anesthesia: Its Technic and Clinical Application. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan Q. Size of human lower thoracic and lumbosacral nerve roots. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:37–42. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kostelic J, Haughton VM, Sether L. Proximal lumbar spinal nerves in axial MR imaging, CT, and anatomic sections. Radiology. 1992;183:239–41. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.1.1549679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfirrmann CW, Oberholzer PA, Zanetti M, et al. Selective nerve root blocks for the treatment of sciatica: evaluation of injection site and effectiveness--a study with patients and cadavers. Radiology. 2001;221:704–11. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213001635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devor M. Unexplained peculiarities of the dorsal root ganglion. Pain. 1999 6:S27–35. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters CM, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Jonas BM, et al. Intravenous paclitaxel administration in the rat induces a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by macrophage infiltration and injury to sensory neurons and their supporting cells. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abram SE, Yi J, Fuchs A, Hogan QH. Permeability of injured and intact peripheral nerves and dorsal root ganglia. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:146–53. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimenez-Andrade JM, Herrera MB, Ghilardi JR, Vardanyan M, Melemedjian OK, Mantyh PW. Vascularization of the dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerve of the mouse: implications for chemical-induced peripheral sensory neuropathies. Mol Pain. 2008;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanani M. Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: from form to function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:457–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Znaor L, Lovric S, Hogan Q, Sapunar D. Association of neural inflammation with hyperalgesia following spinal nerve ligation. Croat Med J. 2007;48:35–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merskey H, Albe-Fessard DG, Bonica JJ, et al. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Pain. 1986;6:249–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:476–87. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Bars D, Gozariu M, Cadden SW. Animal models of nociception. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:597–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan QH, McCallum JB, Sarantopoulos C, et al. Painful neuropathy decreases membrane calcium current in mammalian primary afferent neurons. Pain. 2000;86:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCallum JB, Kwok WM, Sapunar D, Fuchs A, Hogan QH. Painful peripheral nerve injury decreases calcium current in axotomized sensory neurons. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:160–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lirk P, Poroli M, Rigaud M, et al. Modulators of calcium influx regulate membrane excitability in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:673–85. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b7a73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luscher C, Streit J, Quadroni R, Luscher HR. Action potential propagation through embryonic dorsal root ganglion cells in culture. I. Influence of the cell morphology on propagation properties. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:622–33. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemes G, Rigaud M, Weyker PD, et al. Depletion of calcium stores in injured sensory neurons: anatomic and functional correlates. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:393–405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae63b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigaud M, Gemes G, Weyker PD, et al. Axotomy depletes intracellular calcium stores in primary sensory neurons. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:381–92. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold MS, Reichling DB, Hampl KF, Drasner K, Levine JD. Lidocaine toxicity in primary afferent neurons from the rat. Journal of Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:413–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staats PS, Yearwood T, Charapata SG, et al. Intrathecal ziconotide in the treatment of refractory pain in patients with cancer or AIDS: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291:63–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]