Abstract

Outer membrane proteins are structurally distinct from those that reside in the inner membrane and play important roles in bacterial pathogenicity and human metabolism. X-ray crystallography studies on > 40 different outer membrane proteins have revealed that the transmembrane portion of these proteins can be constructed from either β-sheets or less commonly from α-helices. The most common architecture is the β-barrel, which can be formed from either a single anti-parallel sheet, fused at both ends to form a barrel or from multiple peptide chains. Outer membrane proteins exhibit considerable rigidity and stability, making their study through x-ray crystallography particularly tractable. As the number of structures of outer membrane proteins increases a more rational approach to their crystallisation can be made. Herein we analyse the crystallisation data from 53 outer membrane proteins and compare the results to those obtained for inner membrane proteins. A targeted sparse matrix screen for outer membrane protein crystallisation is presented based on the present analysis.

Keywords: Outer Membrane Proteins, Protein Crystallisation, Membrane protein crystallisation, Screen design

Introduction

Outer membrane proteins make up a small but specialised class of membrane proteins, and are located exclusively in the outer membrane (OM) of gram-negative prokaryotes, mitochondria and chloroplasts [1]. In gram-negative bacteria the OM acts as the barrier to the environment and the membrane proteins present are responsible for the uptake of nutrients and defence against external attack. Indeed, the latter function is particularly important for human health, as many of the OM proteins of gram-negative bacteria are actively being investigated as possible vaccine candidates [2, 3]. The mitochondrial OM harbours four integral proteins, which although derived from a bacterial origin have evolved to adapt to the environment within the eukaryotic cell. For example, the voltage dependent anion channel, VDAC, though related to a bacterial porin has acquired additional structural elements that facilitate protein-protein interactions [4].

The first atomic resolution structure of an OM protein, a Porin from Rhodobacter capsulatus, revealed a β-barrel motif arranged as a trimer around a central three-fold axis [5, 6]. Until the recent structural elucidation of outer membrane proteins that contained α-helices in the trans-membrane portion of the protein [7, 8], it was generally believed that all outer membrane proteins consisted of the now canonical β-barrel motif. The β-barrel fold is constructed from beta-pleated sheets that are fused at either end to form barrels of varying sizes and functions [1]. The β-barrel is a particularly stable fold [9] due in large part to the arrangement of the amino acid residues, each strand being linked to the two adjacent strands by a series of main chain hydrogen bonds. It is also capable of forming very tight trimers [10]. In some cases these proteins are responsible for the structural integrity of the OM itself [11].

X-ray crystallography has been the most successful technique for determining the structures of membrane proteins. However, membrane proteins present a number of unique challenges for crystallography [12]. Initial successes in membrane protein X-ray crystallography were made with the bacterial OM proteins, due in large part to their inherent stability [13-15]. The unusually stable conformation of the β-barrel allows some of these proteins to be heterologously over expressed as inclusion bodies within Escherichia coli (E. coli) and subsequently refolded to their native state [16]. Although not all β-barrel membrane proteins can be produced and purified in this way, this stability has undoubtedly contributed to the success in crystallising this class of membrane protein.

Membrane-spanning regions must orientate within the membrane to expose non-polar side chains to the interior of the lipid bi-layer and orientate the polar side chains to the interior of the protein [17]. This raises the interesting question of whether, from a crystallisation standpoint, membrane proteins favour certain conditions for forming regular three-dimensional crystals, regardless of secondary structure and stability. In the present study the crystallisation conditions for 53 detergent solubilised OM proteins, crystallised using the vapour diffusion technique, have been analysed. These results have been compared to a similar analysis on IM proteins to discover both the differences and similarities in the crystallisation conditions. A more fundamental understanding of these conditions should enable a more informed approach to crystallising OM proteins. In addition, we present a targeted sparse matrix crystallisation screen, MemPlus™ for OM proteins to facilitate this aim.

Materials and Methods

A database was built by collating the crystallisation information from all of the available unique β-barrel membrane protein structures in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) (β-MP-database.xls, Supplementary material). Only conditions from proteins crystallised using the vapour diffusion technique were recorded in the database, as this technique is the most commonly used method of screening. It should be noted that dialysis has also proved to be a successful method of crystallisation for this class of membrane protein. This task was greatly facilitated by the Membrane Protein Data Bank (MPDB) (www.mpdb.ul.ie) [18] and the “Membrane Proteins of Known 3D Structure” Web site from the Stephen White laboratory at UC Irvine (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html).

Crystallisation conditions were then divided into the different components, precipitant, buffer, pH, salt(s), additives and detergents along with their respective concentrations. Chemicals were considered additives if their concentration was less than 20 mM, for example, zinc sulphate at 5 mM was counted as an additive and not as a salt. The crystallisation conditions were then analysed by constructing a series of stacked bar charts showing the number of successful crystallisations for each MP family against the individual chemicals for each component of the crystallisation experiments.

The MemPlus™ screen was designed by selecting 48 crystallisation conditions from the currently available unique β-barrel membrane protein structures in the PDB (β-MP-database.xls, Supplementary material); please note that the conditions in the MemPlus™ screen do not replicate the β-MP-database, but serve to provide the broadest range of successful OM protein crystallisation conditions to date. The conditions were chosen to be as non-redundant as possible to avoid unnecessary overlap. The concentrations of the precipitants were increased by 10 %, such that 20 % PEG would become 22 %, to promote nucleation and the formation of crystals. The MemPlus™ screen is currently commercially available through Molecular Dimensions Ltd.

Results and Discussion

Rational detergent selection for OM protein crystallisation

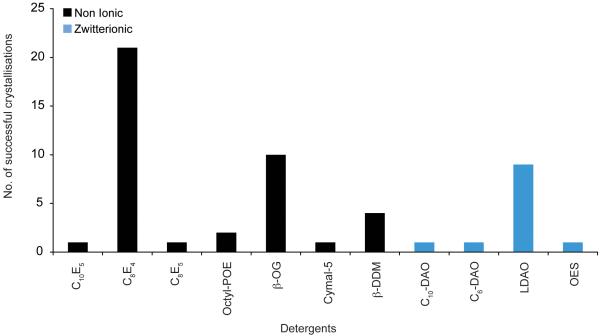

The successful crystallisation of membrane proteins requires the preparation of stable, monodisperse protein-detergent complexes [12]. A suitable detergent must be found that meets at least these two minimal criteria. A further factor in the choice of detergent lies in the size of the micelle formed. Figure 1 shows the detergents that have been successfully used to crystallise OM proteins to date. The detergents belong to either the non-ionic or the zwitterionic detergent classes. No ionic detergents were reported as being successful. The single best detergent was C8E4, which was used to crystallise 20 of the OM proteins analysed. This was followed by n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG), which was used for 10 structures. LDAO was the most successful of the zwitterionic detergents and was used for 9 of the structures. Zwitterionic detergents, although electrically neutral, carry formal positive and negative charges on different atoms. As such, these detergents are often destabilising, especially for α-helical bundle transporters of the IM [19]. The relative success of this detergent class for OM proteins, accounting for 23 % of the structures analysed, attests to the stability of the β-barrel fold. Porins can also carry a substantial negative charge on their surface, which has been proposed to contribute to the overall negative charge of the OM [20]. It is possible that the formal charges on zwitterionic detergents could act to neutralise these surface charges, which would then enable the proteins to pack into a crystal lattice.

Figure 1.

Detergents. The number of successful detergents used to crystallise OM proteins using vapour diffusion are shown. The detergents have been grouped into non-ionic (black) and zwitterionic (blue) detergent classes.

Three-dimensional protein crystals are held together through non-covalent interactions between the protein molecules [21]. Unfortunately, membrane proteins are most often stable in detergents that form large micelles that cover the hydrophobic, apolar regions of the protein, such as Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM). Such detergents are often problematic for crystallisation, as they tend to envelope the protein and limit the number and strength of the very interactions necessary to form well diffracting crystals.

One of the first tasks in developing a strategy for crystallising a membrane protein is therefore to screen different detergents for their ability to not only solubilise and keep the protein in a stable, monodisperse state but must also be suitable for growing well ordered, well diffracting crystals. The β-barrel fold of OM proteins can clearly tolerate small micelle detergents. Both C8E4 and OG have relatively high CMC values, 0.25 and 0.53 % respectively and form small micelles with aggregation numbers between 27-100. The data presented here would suggest that, without any prior knowledge of the behaviour of the OM protein in different detergents, C8E4, OG and LDAO would be good detergents for an initial crystallisation screen. In comparison, DDM, one of the most successful detergents for crystallising α-helical bundle membrane proteins [22], was much less successful in this study. Interestingly, DDM was successful for the OM proteins that have α-helical transmembrane domains, Wza, the translocon for capsular polysaccharides [7] and Porin B from Corynebacterium glutamicum [8].

Choice of precipitant and optimised screening concentrations

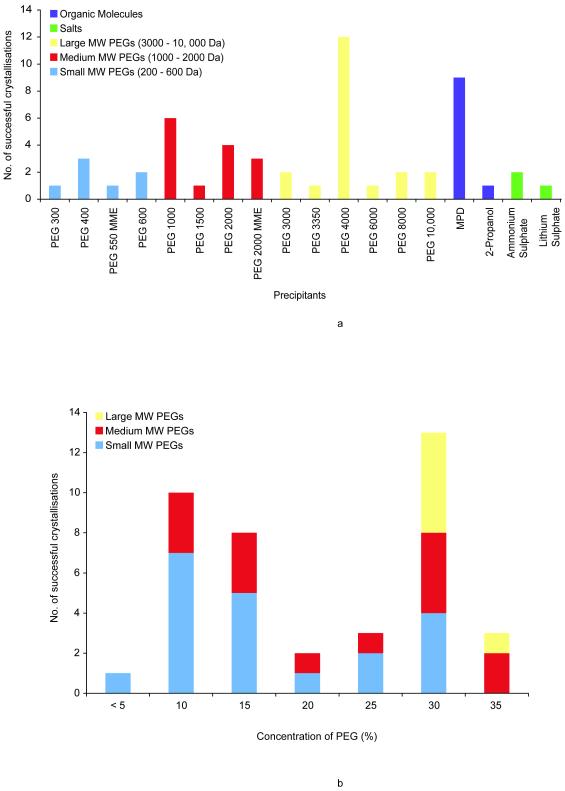

Precipitant choice is a critical parameter for a successful protein crystallisation screen [23, 24]. Figure 2A shows the types of different precipitants that have been used for OM proteins. The precipitants have been grouped into low, medium and high molecular weight polyethylene glycols (PEGs), salts and organic molecules. The most successful precipitants were the PEGs, with PEG 4000 accounting for most structures, 12 in total. The next most successful precipitant was the organic molecule 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), which was used for 9 structures. Salts have not been particularly useful, accounting for only 3 for the structures in the database.

Figure 2.

(A) Precipitants. The different precipitants used to crystallise OM proteins using vapour diffusion are shown. The precipitants have been grouped into organic molecules (purple), salts (green). The polyethylene glycols have been further subdivided by size into small MW (blue), medium MW (red) and large MW (yellow).

(B) Concentration of PEGs. The concentrations of the polyethylene glycols in the OM protein database are shown for each of the MW size groups.

A clear difference in the crystallisation behaviour between OM and IM proteins can be seen in the relatively poor success of the low MW PEGs, which were found to be particularly successful for IM proteins [22]. The high number of OM proteins that were crystallised with MPD is another significant difference. Organic solvents, such as MPD and alcohols bind to the hydrophobic portions of proteins and for this reason, are often destabilising. Their success for OM proteins can be attributed again to the stability of the β-barrel fold. The success of the large MW PEGs, in particular PEG 4000, is less obviously explained. Porins often form either dimers or trimers in the OM and quite a few have large soluble domains that extend into the periplasm and couple to components in the IM, such TolC [25] and VceC [26]. These proteins, in a similar manner to the respiratory complexes of the α-helical bundle IM proteins [22], may behave more like soluble proteins in a crystallisation experiment, where the large MW PEGs were found to be the most successful precipitants [23, 24, 27].

Figure 2B shows the concentration ranges of the PEGs. The large MW PEGs were the most successful precipitant group, accounting for 37 % of the structures. However, the concentrations used varied from < 5 % to 30 % w/v, with no clearly defined optimum concentration. This was true of the medium MW PEGs as well. Where the small MW PEGs were successful, the concentrations varied between 30-35 % v/v, a similar concentration range for IM proteins.

Successful buffers, salts and pH ranges

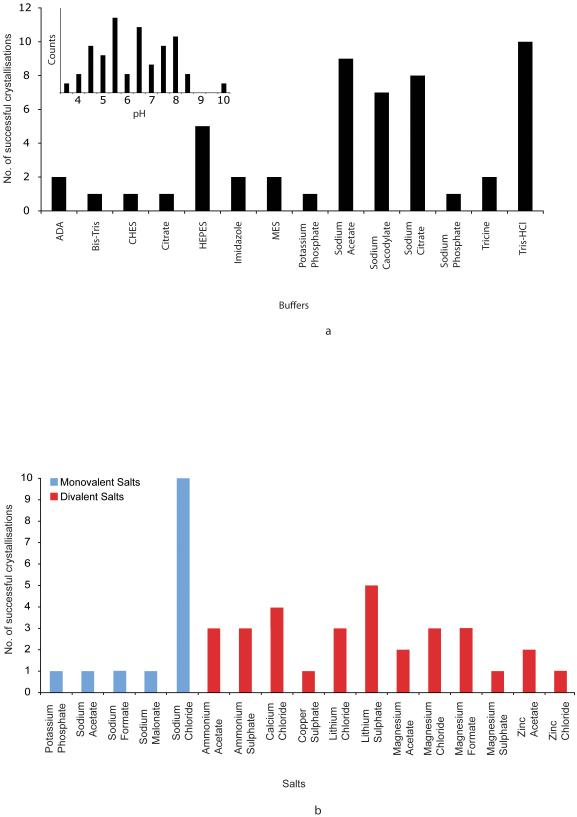

Many variables control and influence the formation of protein crystals and principle among these are the buffers, pH ranges and salts used. Figure 3a shows the different buffers that were used for OM protein crystallisation and the pH covered. The pH ranges from 3.5 to 10 with more than 60 % of the crystals growing at pH values < 7. pH values between 5.5 and 6.5 were the most common followed by 7.5 to 8.0. The buffering chemicals used reflect these values, with the most common buffers being Sodium Acetate, Sodium Citrate and Sodium Cacodylate, which cover pH values from 3.0 to 7.4. Tris-HCl was the most used buffer for pH ranges from 7.4 to 8.5.

Figure 3.

(A) Buffers and pH. The different buffers present in the OM protein database are shown. Inset, the pH distribution of the crystallisation conditions is given, divided into 0.5 pH units.

(B) Salts. The different salts used in the crystallisation conditions are shown. These have been divided into monovalent (blue) and divalent (red) groups.

Figure 3b displays the range of different salts found in the database. 13 out of the 54 conditions contained no salt and of the remaining conditions that did, 14 were monovalent and 31 were divalent salts. Divalent salts were therefore more than twice as successful as monovalent ones, although none stands out as a clear favourite. Of the conditions that contained a monovalent salt, Sodium Chloride was the most common, accounting for 10 out of the 14 conditions. Our results suggest that screening a range of salts is advantageous for OM protein crystallisation, but that divalent salts could be favoured.

Additive screening

Protein crystallisation is an unpredictable event that can be influenced by a myriad of different variables. This is especially true when it comes to the influence of additional small molecules, chemicals, detergents and salts that are collectively known as ‘additives’. In this context ‘additives’ are often considered as chemicals that, although not normally necessary for crystal formation, nevertheless improve the quality, size or number of crystals formed. The analysis of additives presented here is based on the final, published crystallisation conditions; as such it is unknown if these additives were necessary for crystal formation or for crystal improvement. However, it is now well established that small molecule additives can have a profound impact on membrane protein crystallisation [28-30] and this analysis can be used as a guide for selecting a rational additive screening strategy.

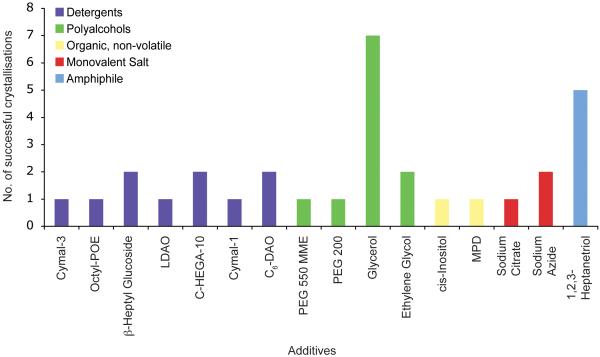

Figure 4 shows the range of additives used for OM protein crystallisation. A total of 16 different chemicals were noted as being used as additives. The most numerous are the detergents with seven, followed by the polyalcohols with four. The remainder consisted of organic molecules and monovalent salts with two each and amphiphiles with one. Additional detergents are often used to reduce the size of the micelle to aid in crystal packing, but may also help to stabilise the membrane protein through specific interactions, perhaps substituting for lipids that were lost during purification [26].

Figure 4.

Additives. The different additives used in the crystallisation conditions are shown. These have been divided into five groups, detergents (purple), polyalcohols (green), organic molecules, non-volatile (yellow), monovalent salts (red) and amphiphiles (blue).

The most common additive was the polyalcohol glycerol. It is unclear if glycerol was used as an additive to help crystallisation or to aid as a cryoprotectant. The high solvent content often found in membrane protein crystals makes transferring them into a cryoprotectant solution potentially harmful. The addition of glycerol to the crystal growth condition can often help with this problem. The next most successful additive was the amphiphile 1,2,3-heptanetriol. Amphiphiles have been used successfully in membrane protein crystallisation to manipulate the size of the detergent micelle [28, 31]. The high number of successes seen with OM proteins suggests that screening a range of different amphiphiles could be advantageous.

The MemPlus™ Screen

There are now a number of structural genomics pipelines being built around membrane proteins [19, 32, 33]. Whilst many of these are concerned with the α-helical bundle type membrane proteins a strong case can be made for revisiting the membrane proteins in the OM of gram-negative bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. To make these pipelines more streamlined and successful, a more rational approach should be taken when screening membrane proteins for possible crystallisation potential. We believe adopting the highly successful approach taken with soluble proteins and mining the currently available structural database for successful crystallisation conditions best serves this aim. In addition to MemGold™ [22], a targeted sparse matrix screen for α-helical bundle type IM proteins, we have developed MemPlus™ (Table 1) a 48 condition targeted screen for OM proteins. This screen currently represents the most up-to-date screen for proteins that reside in the OM.

Table 1.

MemPlus™. A targeted sparse matrix outer membrane protein crystallisation screen

| Salt | Buffer | pH | Precipitant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 0.1 M Sodium Acetate | 5.0 | 30 % v/v PEG 300 |

| 2 | 0.2 M Calcium Chloride | 0.1 M HEPES | 7.0 | 15 % v/v PEG 400 |

| 3 | 1.65 M Ammonium Sulphate |

0.1 M Tris HCl | 8.0 | 2 % v/v PEG 400 |

| 4 | 1.5 M Sodium Formate | 0.05 M Sodium Cacodylate |

5.5 | 30 % v/v PEG 400 |

| 5 | 0.2 M Calcium Chloride | 0.05 M Glycine | 9.0 | 30 % v/v PEG 400 |

| 6 | None | 0.05 M Sodium Acetate | 4.3 | 33 % v/v PEG 550 MME |

| 7 | 0.2 M Potassium Chloride/0.01 M Calcium Chloride |

0.02 M Tris HCl | 7.5 | 30 % v/v PEG 600 |

| 8 | 1.0 M Lithium Sulphate | 0.1 M HEPES | 7.5 | 20 % v/v PEG 600 |

| 9 | 0.3 M Lithium Chloride | 0.02 M Tris | 6.8 | 35 % v/v PEG 600 |

| 10 | None | 0.06 M HEPES/0.04 M Tris HCl |

7.0 | 28 % w/v PEG 1000 |

| 11 | 0.35 M Sodium Chloride | 0.1 M Tricine | 8.0 | 31 % w/v PEG 1000 |

| 12 | 0.2 M Lithium Sulphate | 0.1 M Sodium Citrate | 4.0 | 9 % w/v PEG 1000 |

| 13 | 0.35 M Sodium Chloride | 0.0125 M MOPS | 7.0 | 28 % w/v PEG 1000 |

| 14 | None | 0.02 M Tris | 7.5 | 33 % w/v PEG 1500 |

| 15 | 0.1 M Sodium Chloride | 0.1 M EPPS | 8.0 | 33 % w/v PEG 1500 |

| 16 | None | 0.1 M Sodium Cacodylate | 6.5 | 12 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 17 | None | 0.1 M Sodium Cacodylate | 6.5 | 12.5 % w/v PEG 2000 MME |

| 18 | None | 0.02 M Tris | 7.5 | 12.5 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 19 | 0.4 M Sodium Chloride/0.025 M Magnesium Chloride |

0.02 M Tris | 7.5 | 12.5 % w/v PEG 2000 MME |

| 20 | 0.2 M Ammonium Phosphate |

0.05 M PIPES | 7.0 | 20 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 21 | 0.5 M Sodium Chloride | 0.025 M Tris HCl | 8.0 | 28 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 22 | 0.5 M Magnesium Chloride |

0.05 M Tris | 8.5 | 15 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 23 | 0.3 M Magnesium Chloride |

0.1 M Bicine | 9.0 | 28 % w/v PEG 2000 |

| 24 | 0.1 M Lithium Sulphate | 0.1 M ADA | 6.6 | 13 % w/v PEG 3000 |

| 25 | 0.01 M Calcium Acetate | 0.1 M Tris HCl | 8.5 | 3 % w/v PEG 3000 |

| 26 | 0.2 M Magnesium Actetate | 0.1 M MES | 6.0 | 10 % w/v PEG 3350 |

| 27 | 0.2 M Magnesium Acetate | 0.05 M Sodium Cacodylate |

6.5 | 11 % w/v PEG 3350 |

| 28 | 0.2 M Magnesium Acetate | 0.1 M Bis Tris | 6.5 | 11 % w/v PEG 3350 |

| 29 | 0.1 M Lithium Chloride/0.025 M Magnesium Chloride |

0.01 M Tris HCl | 7.5 | 14 % w/v PEG 4000 |

| 30 | 0.2 M Ammonium Sulphate |

0.1 M CHES | 10.0 | 14 % w/v PEG 4000 |

| 31 | 0.15 M Potassium Sodium Tartrate |

0.05 M ADA | 6.6 | 20 % w/v PEG 4000 |

| 32 | 0.7 M Sodium Chloride | 0.14 M Sodium Phosphate | 7.0 | 25 % w/v PEG 4000 |

| 33 | 0.15 M Zinc Acetate/0.05 M Zinc Chloride |

0.05 M Tris | 7.5 | 13 % w/v PEG 6000 |

| 34 | 0.2 M Ammonium Chloride |

0.15 M Tricine | 8.0 | 15 % w/v PEG 6000 |

| 35 | None | 0.025 M Potassium Phosphate |

5.1 | 13 % w/v PEG 8000 |

| 36 | 0.15 M Zinc Acetate | 0.08 M Sodium Cacodylate |

6.5 | 15 % w/v PEG 8000 |

| 37 | 0.1 M Magnesium Acetate | 0.1 M PIPES | 6.8 | 30 % w/v PEG 8000 |

| 38 | 1.4 M Ammonium Sulphate/0.1 M Ammonium Acetate |

None | 4.5 | 4 % v/v 2-propanol |

| 39 | 0.5 M Sodium Acetate | 0.05 M Tris HCl/0.1 M Imidazole |

8.0 | 25 % v/v MPD |

| 40 | 0.001 M Calcium Chloride | 0.1 M Bis Tris | 6.0 | 27 % v/v MPD |

| 41 | 0.2 M Ammonium Acetate | 0.1 M Sodium Citrate | 5.5 | 30 % v/v MPD |

| 42 | 0.2 M Calcium Chloride | None | 30 % v/v 2-propanol | |

| 43 | 1.3 M Ammonium Sulphate |

0.1 M Tris HCl | 8.5 | None |

| 44 | 0.5 M Sodium Chloride | 0.1 M Sodium Citrate | 4.5 | 28 % v/v MPD |

| 45 | 0.2 M Sodium Chloride | 0.1 M HEPES | 7.0 | 35 % v/v MPD |

| 46 | 0.3 M Calcium Chloride | 0.1 M PIPES | 6.5 | None |

| 47 | 0.1 M Ammonium Sulphate |

0.1 M Glycine | 3.8 | 25 % v/v TEG |

| 48 | 0.15 M Magnesium Chloride |

0.05 M EPPS | 8.0 | 14 % v/v MPEG |

Supplementary Material

Description of Supplementary material: A copy of the database used for the analysis in Excel format: beta-MP-database.xls

Acknowldegements

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Membrane Protein Structure Initiative consortium (www.mpsi.ac.uk). The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Wellcome Trust funded Membrane Protein Laboratory at the Diamond Light Source Ltd.

Abbreviations

- ADA

N-(2-Acetamido)iminodiacetic Acid

- Bicine

N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine

- Bis Tris

Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-tris(hydroxymethyl)methane

- CHES

2-(N-Cyclohexylamino)ethane sulfonic Acid

- EPPS

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-propanesulfonic acid

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MME

Monomethylether

- MPD

2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol

- MPEG

methoxy polyethylene glycol

- MOPS

3-{N-morpholino] propanesulfonic acid

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PIPES

Piperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid

- TEG

triethylene-glycol

- Tricine

N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]glycine

- Tris

2-Amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- Tri HCl

2-Amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol, hydrochloride

- cis-Inostitol

cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-cyclohexanehexol

- Octyl-POE

Octyl-Polyoxyethylene

- Cymal-1

Cyclohexyl-methyl--D-maltoside

- Cymal-5

5-Cyclohexyl-1-pentyl-D-maltoside

- LDAO

Lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide

- OES

N-Octyl-2-Hydroxyethylsulfoxide

- C8E4

Octyl tetraethylene glycol ether

- C8E5

Octyl pentaethylene glycol ether

- C10-DAO

Decyl dimethyl amino N-oxide

- C6-DAO

Hexyl dimethyl amino N-oxide

- C10E5

Decyl pentaethylene glycol ether

- PDB

Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org)

References

- [1].Schulz GE. Transmembrane beta-barrel proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2003;63:47–70. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(03)63003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Larbig M, Mansouri E, Freihorst J, Tummler B, Kohler G, Domdey H, Knapp B, Hungerer KD, Hundt E, Gabelsberger J, von Specht BU. Safety and immunogenicity of an intranasal Pseudomonas aeruginosa hybrid outer membrane protein F-I vaccine in human volunteers. Vaccine. 2001;19:2291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hamid N, Jain SK. Characterization of an outer membrane protein of Salmonella that confers protection against typhoid. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/CVI.00093-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zeth K, Meins T, Vonrhein C. Approaching the structure of human VDAC1, a key molecule in mitochondrial cross-talk. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9144-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Weiss MS, Abele U, Weckesser J, Welte W, Schiltz E, Schulz GE. Molecular architecture and electrostatic properties of a bacterial porin. Science. 1991;254:1627–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1721242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Weiss MS, Kreusch A, Schiltz E, Nestel U, Welte W, Weckesser J, Schulz GE. The structure of porin from Rhodobacter capsulatus at 1.8 A resolution. FEBS Lett. 1991;280:379–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dong C, Beis K, Nesper J, Brunkan-Lamontagne AL, Clarke BR, Whitfield C, Naismith JH. Wza the translocon for E. coli capsular polysaccharides defines a new class of membrane protein. Nature. 2006;444:226–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ziegler K, Benz R, Schulz GE. A putative alpha-helical porin from Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Koebnik R. Structural and functional roles of the surface-exposed loops of the beta-barrel membrane protein OmpA from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3688–94. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3688-3694.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moraes TF, Bains M, Hancock RE, Strynadka NC. An arginine ladder in OprP mediates phosphate-specific transfer across the outer membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:85–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sonntag I, Schwarz H, Hirota Y, Henning U. Cell envelope and shape of Escherichia coli: multiple mutants missing the outer membrane lipoprotein and other major outer membrane proteins. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:280–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.1.280-285.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Iwata S, Tsigelny IF. Methods and Results in Crystallization of Membrane Proteins. 2003. p. 355. IUL Biotechnology Series. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Phale PS, Philippsen A, Kiefhaber T, Koebnik R, Phale VP, Schirmer T, Rosenbusch JP. Stability of trimeric OmpF porin: the contributions of the latching loop L2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15663–70. doi: 10.1021/bi981215c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rosenbusch JP. Characterization of the major envelope protein from Escherichia coli. Regular arrangement on the peptidoglycan and unusual dodecyl sulfate binding. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:8019–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schindler M, Rosenbusch JP. Structural transitions of porin, a transmembrane protein. FEBS Lett. 1984;173:85–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bannwarth M, Schulz GE. The expression of outer membrane proteins for crystallization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00711-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].von Heijne G. Membrane-protein topology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:909–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Raman P, Cherezov V, Caffrey M. The Membrane Protein Data Bank. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:36–51. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Newstead S, Kim H, von Heijne G, Iwata S, Drew D. High-throughput fluorescent-based optimization of eukaryotic membrane protein overexpression and purification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13936–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704546104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Swanson J, Dorward D, Lubke L, Kao D. Porin polypeptide contributes to surface charge of gonococci. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3541–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3541-3548.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Branden CI, Tooze B. Introduction to Protein Structure. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Newstead S, Ferrandon S, Iwata S. Rationalizing alpha-helical membrane protein crystallization. Protein Sci. 2008;17:466–72. doi: 10.1110/ps.073263108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kimber MS, Vallee F, Houston S, Necakov A, Skarina T, Evdokimova E, Beasley S, Christendat D, Savchenko A, Arrowsmith CH, Vedadi M, Gerstein M, Edwards AM. Data mining crystallization databases: knowledge-based approaches to optimize protein crystal screens. Proteins. 2003;51:562–8. doi: 10.1002/prot.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Page R, Stevens RC. Crystallization data mining in structural genomics: using positive and negative results to optimize protein crystallization screens. Methods. 2004;34:373–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Koronakis V, Sharff A, Koronakis E, Luisi B, Hughes C. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature. 2000;405:914–9. doi: 10.1038/35016007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Federici L, Du D, Walas F, Matsumura H, Fernandez-Recio J, McKeegan KS, Borges-Walmsley MI, Luisi BF, Walmsley AR. The crystal structure of the outer membrane protein VceC from the bacterial pathogen Vibrio cholerae at 1.8 A resolution. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15307–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wooh JW, Kidd RD, Martin JL, Kobe B. Comparison of three commercial sparse-matrix crystallization screens. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:769–72. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903002919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Michel H. Three-dimensional crystals of a membrane protein complex. The photosynthetic reaction centre from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. J Mol Biol. 1982;158:567–72. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schertler GF, Bartunik HD, Michel H, Oesterhelt D. Orthorhombic crystal form of bacteriorhodopsin nucleated on benzamidine diffracting to 3.6 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:156–64. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sorensen TL, Olesen C, Jensen AM, Moller JV, Nissen P. Crystals of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:704–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Timmins PA, Hauk J, Wacker T, Welte W. The influence of heptane-1,2,3-triol on the size and shape of LDAO micelles. Implications for the crystallisation of membrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 1991;280:115–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80217-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Drew D, Lerch M, Kunji E, Slotboom DJ, de Gier JW. Optimization of membrane protein overexpression and purification using GFP fusions. Nat Methods. 2006;3:303–13. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0406-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Drew D, Newstead S, Sonoda Y, Kim H, von Heijne G, Iwata S. GFP-based optimization scheme for the overexpression and purification of eukaryotic membrane proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:784–98. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Supplementary material: A copy of the database used for the analysis in Excel format: beta-MP-database.xls