Abstract

Background

Behavioral disinhibition (externalizing/impulsivity) and behavioral inhibition (internalizing/anxiety) may contribute to the development of alcohol abuse and dependence. But tests of person-by-environment interactions in predicting alcohol use disorders are needed. This study examined the extent to which interactions between behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition and family management during adolescence predict alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence at age 27.

Methods

This study used longitudinal data from a community sample of 808 men and women interviewed from age 10 to 27 in the Seattle Social Development Project. Zero-order correlations followed by a series of nested regressions examined the relationships between individual characteristics (behavioral disinhibition and behavioral inhibition/anxiety) and environment (good versus poor family management practices during adolescence) in predicting alcohol abuse and dependence criterion counts at age 27.

Results

Behavioral disinhibition and poor family management predicted increased likelihood of both alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence at age 27. Behavioral inhibition/anxiety was unrelated to both outcomes. Youths high in behavioral disinhibition were at increased risk for later alcohol abuse and dependence only in consistently poorly managed family environments. In consistently well-managed families, high levels of behavioral disinhibition did not increase risk for later alcohol abuse or dependence.

Conclusions

Behavioral disinhibition increases risk for alcohol abuse and dependence in early adulthood only for individuals who experience poor family management during adolescence. Interventions seeking to reduce environmental risks by strengthening consistent positive family management practices may prevent later alcohol abuse and dependence among individuals at risk due to behavioral disinhibition.

Keywords: alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition, anxiety, family management, person-environment interaction, longitudinal

1.0 Introduction

In reviews of research in clinical, community and twin samples, behavioral disinhibition has consistently been shown to predict problem alcohol use and alcohol abuse and dependence from early childhood onwards (Chassin et al., 2004; McGue et al., 1997; Sher et al., 2000; Hill et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2001; Hawkins et al., 1992; Kandel, 1978; Zucker, 2008). Behavioral disinhibition has been defined as the inability to inhibit socially undesirable or restricted actions (Iacono et al., 2008), or similarly, the inability or unwillingness or failure to inhibit behavioral impulses even in the face of negative consequences (Sher and Trull, 1994). The concept is related to the constellation of individual difference characteristics predictive of alcoholism suggested by Cloninger (1988; 1987) that includes high novelty seeking, low harm avoidance, and high reward dependence. A review of research findings testing the strength of Cloninger’s tridimensional theory in predicting substance use disorders found most consistent support for novelty seeking, some support for harm avoidance and inconsistent support for reward dependence (Howard et al., 1997).

In addition to behavioral disinhibition, some researchers have emphasized the importance of internalizing symptoms in the etiology of alcohol use disorder, suggesting, for example that individuals high in anxiety, depression or with poor reactions to stress might be attempting to medicate their symptoms with alcohol, thus leading to alcohol problems (Clark and Sayette, 1993; Swendsen et al., 2000; Khantzian and Albanese, 2008). Findings linking anxiety, depression and stress to problem alcohol use, however, have been less consistent than those for behavioral disinhibition. Several researchers have found associations between anxiety and depression and alcohol dependence cross-sectionally (Gratzer et al., 2004; Hasin and Nunes, 1997; McGue et al., 1997; Weitzman, 2004; Slutske et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2000). Guo et al. (2001) found that internalizing behavior at age 10 predicted an alcohol abuse and dependence composite at age 21, however, Sher et al. (2000) found that anxiety/harm avoidance in late adolescence did not predict abuse or dependence prospectively across a 7-year period in adulthood. Recent reviews of the literature note that evidence for the role of an internalizing pathway in the prediction of alcohol abuse and dependence remains inconsistent (NIAAA, 2004/2005; Zucker, 2006; Zucker, 2008), but that there have been too few longitudinal investigations to draw final conclusions (Schuckit and Hesselbrock, 2004).

The constructs of behavioral disinhibition and anxiety/harm avoidance are similar, respectively, to the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) and the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) proposed by Gray (1987a). The BAS is seen as sensitive reward and is thought to regulate desire-related motivation, while the BIS is viewed as sensitive punishment and frustration, and is hypothesized to promote avoidance behavior and feelings of anxiety (Gray, 1987b; Corr, 2004; Knyazev, 2004). These two concepts of BAS and BIS provide the framework for organizing individual difference characteristics in the present study. As with behavioral disinhibition, previous work has consistently shown measures of BAS to be related to alcohol and other drug problems (e.g., Zisserson and Palfai, 2007; O’Connor and Colder, 2005; Jorm et al., 1999). As with internalizing symptoms, however, the findings on measures of BIS have been mixed, with some studies finding a relationship to alcohol problems (Loxton and Dawe, 2001; Kimbrel et al., 2007), while other studies do not (Kambouropoulos and Staiger, 2007; Johnson et al., 2003; Franken et al., 2006).

Koob and colleagues have proposed a neurobiological allostatic model of drug and alcohol dependence consistent with the BAS/BIS framework where onset and escalation are primarily a function of impulse control disorders associated with pleasure, while dependence is more of a compulsive disorder associated with anxiety and stress (Koob et al., 2004; Koob and Le Moal, 2001; Koob and Le Moal, 2008; Le Moal and Koob, 2007). Based on this model, it is reasonable to hypothesize that behavioral disinhibition would be associated with both alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, while individual differences in inhibition/anxiety would be associated with alcohol dependence. Koob and colleagues note, however, that individual differences in sensitivity to disinhibition and trait anxiety are likely to interact with environmental experience in determining vulnerability to dependence (Koob and Le Moal, 2008). This person-environment hypothesis has not been tested.

Further evidence supporting the roles of behavioral disinhibition and inhibition/anxiety comes from studies of molecular genetics. Polymorphisms in genes involved in regulating the dopamine system have been related to both behavioral disinhibition and alcohol problems (Limosin et al., 2003; Blum et al., 1990; Hopfer et al., 2005; Vanyukov et al., 1998). Genes involved in regulating the serotonergic and GABAergic systems have been related to behavioral disinhibition, anxiety and depression, and alcohol problems (Dick et al., 2006; Edenberg et al., 2004; Dick et al., 2004; Eley et al., 2004; Hill et al., 2002; Otani et al., 2005), and results from one molecular genetic study indicate that anxiety mediates the influence of GABRA2 on alcoholism (Enoch et al., 2006). These findings support the idea that behavioral disinhibition and behavioral inhibition/anxiety may serve as individual difference pathways for genetic influence on alcohol abuse and dependence (Gottesman and Gould, 2003).

Researchers examining the role of genetic and individual differences on alcohol abuse and dependence have emphasized that these influences must be examined in the context of their interaction with the environment (Kreek et al., 2005; Moffitt, 2005; Neiderhiser, 2001; Reiss and Neiderhiser, 2000; Rutter et al., 2006). Significant environmental predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence have been found in the family, peer group, school and neighborhood domains (for a review see Hawkins et al., 1992). Of these, socialization processes in the family may be particularly important in the development of alcohol abuse and dependence (Clark, 2004; NIAAA, 2004/2005; Dishion and Kavanagh, 2003). Specifically, proactive family management practices, including parental monitoring, rules, and norms guiding adolescents’ social activities have been linked repeatedly to later alcohol problems, abuse and dependence (Guo et al., 2001; Hawkins et al., 1992; Clark et al., 1998; Fothergill and Ensminger, 2006; Ledoux et al., 2002).

Though often cited as an important area of research, few studies testing person × environment interaction models of problem drinking development have been published (NIAAA, 2004/2005; Zucker, 2008). In a study of college freshmen, Grekin & Sher (2006) found that both behavioral undercontrol and environmental alcohol risk (membership in a Greek organization vs. not) predicted alcohol dependence symptoms, and that their interaction was significant such that the risk associated with behavioral undercontrol was exacerbated by those at greater environmental risk. Similarly, in a study of sibling data from a large family study of alcoholism, Grucza and colleagues (2006) found that novelty seeking and family alcohol risk (parental alcohol dependence) predicted adult alcohol dependence, and that their interaction was also significant such that the risk associated with high novelty seeking was magnified in families with parental alcohol dependence. Both of these studies show that the impact of dispositional risk for alcohol dependence can be exacerbated in the presence of environmental risk.

Environmental factors buffering the impact of individual risk for alcohol use disorders have not been well identified. In addition to the main effects of proactive family management discussed above, good family management practices during adolescence may interact with behavioral disinhibition and behavioral inhibition/anxiety. Moffitt and colleagues have hypothesized that children high in neurobehavioral risk (e.g., high behavioral disinhibition or high anxiety or depression) and who are raised in poorly managed, dysfunctional families are much more likely to follow a course of early onset, life-course persistent problems (Moffitt, 1993; Raine et al., 2005). Moffitt and colleagues suggest a mechanism of evocative person-environment correlation such that a child high in behavioral disinhibition provokes family conflict and is more difficult to manage. Yet, some parents may be able to successfully implement consistent monitoring, rules and guidelines and appropriate rewards and costs for child behavior. Youths at constitutional risk for alcohol problems, either because of high behavioral disinhibition or because of high trait anxiety, but who are raised in well-managed families should be at reduced risk for life course persistent problems. Thus the effects of behavioral disinhibition or behavioral inhibition on development may depend, in part, on whether or not the child is raised in a consistently well-managed family. These hypotheses have not been tested for alcohol abuse and dependence.

Study Research Questions

Using a community-based longitudinal design, the current study examined person-environment interactions in the prediction of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence at age 27. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions. (1) Do early adolescent behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition/anxiety, and good family management predict alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood at age 27? (2) Does good family management during adolescence moderate and, specifically, reduce the effects of behavioral disinhibition (2a) and behavioral inhibition/anxiety (2b) on alcohol abuse and dependence at age 27? And, (3) are the direct and moderated effects of behavioral inhibition/anxiety more predictive of alcohol dependence than of alcohol abuse (following Koob and colleagues, as discussed above)?

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

The sample consists of participants in the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) who were followed from ages 10 to 27. The sample of 808 youths and their parents, originally recruited from 18 elementary schools in urban Seattle in 1985, includes near equal numbers of males and females (50%) and is ethnically diverse: 47% Caucasian; 26% African-American; 22% Asian-American; and 5% Native American. Fifty-two percent experienced poverty in childhood, as measured by eligibility for the federal school lunch program at ages 10–13. At age 27, 754 (93.3% of the sample) were interviewed. Detailed summaries of the SSDP sample and study methods can be found in earlier papers (Hawkins et al., 2005; Hill et al., 2005; Hill et al., 2000). All procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington. All participants provided informed consent prior to being included in the study.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol Dependence

Alcohol abuse and dependence at age 27 were assessed through computer-assisted, face-to-face interviews using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DISC, Robins et al., 1998). An Alcohol Abuse Criterion Index was computed at age 27 as the number of DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) met for alcohol abuse disorders summed and coded 0–4. An Alcohol Dependence Criterion Index was computed as the number of DSM-IV criteria met for alcohol dependence disorders, summed and coded 0–7. Research by Hasin et al. (2006) suggests that criterion count measures provide more information than diagnoses per se in etiological analyses. Criterion index measures were somewhat skewed (2.57 and 2.60, respectively), and were log transformed for regressions (resulting skews, 1.90 and 1.54, respectively).

2.2.2 Behavioral Disinhibition

Behavioral disinhibition was assessed through a 5-item scale asking SSDP respondents at ages 14 and 15 “How many times have you done the following things?” Done what feels good, no matter what?; Gone to a wild, out-of-control party?; Upset or annoyed adults just for the fun of it?; Done something dangerous because someone dared you to do it?; Done crazy things even if they are a little dangerous? Response options ranged from 1 = “never” to 6 = “once a week or more.” Since behavioral disinhibition is considered to be a relatively stable individual difference characteristic (Iacono et al., 2008; McGue et al., 1999; O’Connor and Colder, 2005; Young et al., 2000), and its average annual cross-age stability in the present data from age 14 to 18 was high (r =.75, p < .001), scales consisting of the mean of these standardized items were created at the earliest ages available (ages 14 and 15; Cronbach’s alpha = .78 and .80, respectively), and averaged to reflect mean early adolescent (age 14–15) behavioral disinhibition.

2.2.3 Behavioral Inhibition or Anxiety

Behavioral inhibition/trait anxiety was assessed through a 6-item scale drawn from the Child Behavior Checklist-Self Report (Lengua et al., 2001; Achenbach et al., 2001). Items included: I worry a lot; I am nervous or tense; I am too fearful or anxious; I am self-conscious or easily embarrassed; I feel that I am overly anxious to please others; I am afraid of making mistakes. Response options ranged from 1 = “not true” to 3 = “often true”. As with behavioral disinhibition, the annual cross-age stability in behavioral inhibition from age 14 to 18 was high (r=.72, p<.001), so items were standardized and averaged across ages 14 and 15 (Cronbach’s alpha = .74 and .77, respectively) to reflect mean early adolescent behavioral inhibition.

2.2.4 Family Management

Measures of parents’ family management practices were developed from youths’ reports at ages 11–14. At each age, youths responded to 6 items. They were asked: When you are away from home, do your parents know where you are and who you are with?; When you misbehave, do your parents take time to calmly discuss what you have done wrong?; The rules in my family are clear; My parents praise me for my school achievements; My parents notice when I am doing a good job and let me know about it; My parents put me down (reversed). Responses were scored on a 4-point scale (NO!, no, yes, YES!); scores for each indicator were standardized and combined at each age. Standardized scale reliabilities range from .66 to .71. Composite scales at each age were dichotomized using a median split to characterize high and low levels of good family management.

For the present study, we focused the analyses on youths in consistently well-managed or consistently poorly-managed families in the transition to adolescence. In a prior paper examining family management during this developmental period (Herrenkohl et al., 2006), we employed growth mixture models (Muthén and Muthén, 2000; Nagin and Tremblay, 2001) implemented through a customized SAS macro (Jones et al., 2001) of these scales from 11–14 to identify family management trajectory groups. A three-group solution provided the most efficient balance between parsimony and fit: consistently well-managed families (43%), consistently poorly managed families (43%) and improving family management (14%). The average probabilities for assignment of individuals to groups were .98, .93 and .88 for well-managed, poorly managed and improving family management respectively, indicating very low classification error in each case. For the present paper examining person × environment interactions, youths in consistently well managed (coded as 1) and consistently poorly managed families (coded as 0) were selected for analyses, representing 86% of the total sample.

2.2.5 Control Variables

Ethnicity, gender and poverty were included as sociodemographic control variables in analyses. Ethnicity and gender were self-reported by respondents. Analyses focused on the three main ethnic groups in the sample that had sufficient numbers for comparison: African Americans, Asian Americans and Caucasian Americans. Childhood poverty (age 10–13) was assessed through a measure of family eligibility for the federal school lunch program when children were in the fifth, sixth, or seventh grades. Since early onset drinking has also been shown to be a predictor of adult alcohol use disorder (Guo et al., 2001; Hawkins et al., 1997; Hingson et al., 2006), past-month drinking at age 12 was included as a control variable, and was assessed through youth self-report to the question How many times have you drunk beer, wine, wine coolers, whiskey, gin, or other liquor in the past month? (response options: 1 = “never” to 4 = “more than four times”). Eighteen percent of the sample reported some level of alcohol use in the past month at age 12.

2.3 Statistical Analysis Plan

Preliminary analyses included univariate descriptives and zero-order correlations. To examine the primary research hypotheses regarding the interactive effects of person and environmental variables on alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence criteria at age 27, a series of nested regressions were also conducted. To compute the interaction terms, behavioral disinhibition and behavioral inhibition were each centered on their group mean (to reduce correlation between the interaction and main effects terms) and multiplied times the family management measure (0/1). At each step, model R2’s were calculated, as well as significance of the change in R2 following Cohen and Cohen (1983). As described above, the analysis sample for all analyses consisted of Caucasian, African American and Asian American youths from consistently well-managed and consistently poorly managed families, representing 86% of the total sample, n=640. To deal with missing data (5.05% missingness overall), all analyses were conducted in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2007) using full information maximum likelihood.

A portion of the sample was exposed to a multicomponent preventive intervention in the elementary grades, consisting of teacher training, parenting classes, and social competence training for children (Hawkins et al., 1999). While differences in prevalences and means have been observed between the intervention and control groups on variables (Hawkins et al., 1999; Hawkins et al., 2005) prior analyses have shown few differences in the covariance structures of the groups (Catalano and Hawkins, 1996; Hill et al., 2005; McCarty et al., in press). Analyses for this report were based on the full sample after examining possible differences in the relationships between predictor and outcomes, comparing the control group and the intervention conditions combined. A model constraining the covariances among the variables in the analysis to be equal across intervention and control groups fit the data well (NFI: .997; CFI: 1.000), thereby supporting a single-group analysis.

3.0 Results

3.1 Descriptive Results and Zero-Order Correlations

At age 27, 20.2% of the analysis sample met criterion for alcohol abuse and 8.2% met criterion for alcohol dependence at age 27. Prevalences, means, standard deviations and bivariate Pearson Correlations for model variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations between model variables (n=640).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 African Americana | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 2 Asian Americana | −0.325*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 3 Poverty - Ages 10–13 | 0.311*** | 0.170*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4 Gender (Male) | 0.013 | 0.048 | −0.032 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5 Past-month Drinking Age 12 | −0.027 | −0.145** | −0.019 | 0.122** | 1.000 | |||||

| 6 Behavioral Disinhibition Age 14–15 | 0.127*** | −0.266*** | −0.028 | 0.226*** | 0.321*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 7 Behavioral Inhibition - Age 14–15 | −0.071+ | 0.069+ | 0.079* | −0.158*** | −0.061 | 0.015 | 1.000 | |||

| 8 Family Management - Age 11–14 | 0.111** | −0.131*** | −0.069+ | −0.112** | −0.092* | −0.132*** | −0.193*** | 1.000 | ||

| 9 Alcohol Abuse - Age 27 | −0.077+ | −0.021 | −0.061 | 0.224*** | 0.133** | 0.153*** | −0.037 | −0.083* | 1.000 | |

| 10 Alcohol Dependence - Age 27 | −0.087* | 0.004 | −0.085* | 0.262*** | 0.122* | 0.146*** | −0.022 | −0.089* | 0.729*** | 1.000 |

| Prevalence/Mean | 28.3% | 21.1% | 50.9% | 51.0% | 1.290 | 1.973 | 1.667 | 49.7% | 0.173 | 0.295 |

| SD | - | - | - | - | 0.681 | 0.893 | 0.840 | - | 0.362 | 0.516 |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .10;

vs. Caucasian

Addressing research question 1, the correlations in Table 1 show that adolescent behavioral disinhibition and consistently good family management in adolescence are significantly related to alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms at age 27, while behavioral inhibition/anxiety is related to neither outcome. Among the control variables, African Americans are less likely than Caucasians to report age 27 alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms, youths in poverty are less likely to report later alcohol dependence symptoms, males are more likely to report both alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms than females, and past-month drinking at age 12 is significantly related to both more alcohol abuse symptoms and more alcohol dependence symptoms at age 27. Note also, though not explicitly hypothesized, that Table 1 provides evidence of person-environment correlation as well: persons in poorly managed families tend to be higher in behavioral disinhibition and higher in behavioral inhibition. This finding does not compromise examination of person-environment interaction, because when main effects are correlated, their correlation is partialled out of the interaction contribution (Cohen and Cohen, 1983).

Addressing research question 2, whether good family management practices during adolescence buffer the effects of behavioral disinhibition (Q2a) and behavioral inhibition (Q2b) on alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood, zero-order correlations were calculated within consistently well-managed and consistently poorly managed family groups. Results in Table 2 show that in consistently poorly managed families (below the diagonal) behavioral disinhibition significantly predicts age 27 alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. In consistently well-managed families behavioral disinhibition is unrelated to later alcohol abuse and dependence. However, as with the full sample analyses, behavioral inhibition is unrelated to either alcohol abuse or dependence in both poorly managed and well-managed families. Thus, good family management does appear to interact with behavioral disinhibition, but not behavioral inhibition/anxiety in the longitudinal prediction of alcohol abuse and dependence. In addition, these analyses do not support the idea (question 3) that behavioral inhibition/anxiety is a better predictor of alcohol dependence than of alcohol abuse.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between person variables and alcohol abuse and dependence in poorly managed families (below the diagonal) and in well-managed families (above the diagonal).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Behavioral Disinhibition - Age 14–15 | 1.000 | 0.095 | 0.032 | 0.060 |

| 2 Behavioral Inhibition - Age 14–15 | −0.105+ | 1.000 | −0.067 | −0.061 |

| 3 Alcohol Abuse - Age 27 | 0.224*** | −0.043 | 1.000 | 0.661*** |

| 4 Alcohol Dependence - Age 27 | 0.192*** | −0.021 | 0.775*** | 1.000 |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .10

3.2 Sequential Nested Regression Models

Analyses next sought to determine if adolescent person and environment characteristics predict adult alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms once sociodemographic factors are controlled, and sought to examine whether the relationship between person variables and later alcohol problems depends upon family environment through a nested sequence of linear regression models.

Age 27 Alcohol Abuse

Table 3 presents the results of 3 nested regression models testing the study hypotheses. Sociodemographic control measures of ethnicity, poverty, gender and early drinking (age 12) are included in Model 1. This model shows that ethnicity (African American vs. Caucasian), gender, and early drinking each uniquely predict age 27 alcohol abuse. Model 2 then examines the main effects of the individual difference and family environment measures on later alcohol abuse, controlling for the measures in Model 1. Results show that only behavioral disinhibition still marginally predicts alcohol abuse at age 27 (β = +0.086, p < .06). Behavioral inhibition still does not predict later alcohol abuse, and the main effect relationship for family management seen in the zero-order correlations is no longer significant. Sensitivity analyses including each control variable separately indicated the drop to nonsignificance for family management came primarily from the inclusion of early drinking and somewhat from the inclusion of behavioral disinhibition (not tabled). Model 3 then examines the contribution of person × environment interactions in the prediction of age 27 abuse symptoms. Results show that the interaction between behavioral disinhibition and family management significantly predicts alcohol abuse (β = −0.250, p < .012), with ethnicity, poverty, gender, early drinking, and the main effects of behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition and family management in the model. Although no main effect of behavioral inhibition on alcohol abuse or dependence was found, its interaction with family management was examined in the event its effects were revealed through interaction with environment. However, this hypothesis was not supported. The effects of behavioral inhibition on later alcohol abuse and dependence are unaffected by good/poor family management.

Table 3.

Multivariate linear regression analyses predicting alcohol abuse at age 27.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| 1 African Americana | −0.082 | 0.074 | −0.087 | 0.060 | −0.083 | 0.072 |

| 2 Asian Americana | −0.038 | 0.405 | −0.026 | 0.566 | −0.019 | 0.684 |

| 3 Poverty - Ages 10–13 | −0.019 | 0.661 | −0.021 | 0.628 | −0.029 | 0.512 |

| 4 Male | 0.214 | 0.001 | 0.190 | 0.001 | 0.194 | 0.001 |

| 5 Past-month Drinking Age 12 | 0.103 | 0.032 | 0.071 | 0.164 | 0.066 | 0.193 |

| 7 Behavioral Disinhibition (BDI) - Age 14–15 | 0.086 | 0.060 | 0.177 | 0.002 | ||

| 8 Behavioral Inhibition/Anxiety (BI/A) - Age 14–15 | −0.015 | 0.723 | 0.010 | 0.859 | ||

| 6 Family Management Age – 11–14 | −0.042 | 0.311 | 0.244 | 0.227 | ||

| 9 BDI × Family Management | −0.250 | 0.012 | ||||

| 10 BI/A × Family Management | −0.060 | 0.732 | ||||

| R2 | 7.0% | 0.001 b | 7.7% | 0.165 b | 8.6% | 0.038 b |

= vs. Caucasian;

= Significance of change in R2.

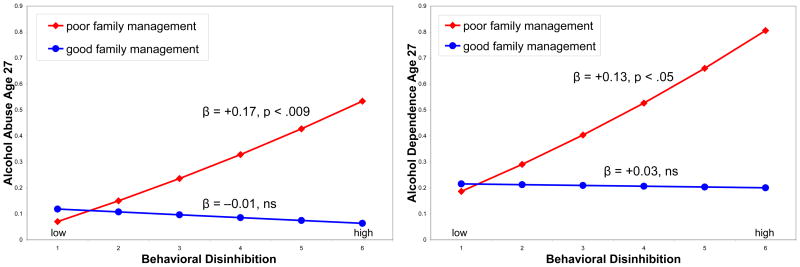

Regression models that included ethnicity, poverty, gender, early drinking, and the main effects of behavioral disinhibition, and behavioral inhibition were conducted separately within the two family management groups in predicting age 27 alcohol abuse. Results showed that behavioral disinhibition significantly predicts age 27 alcohol abuse within poorly managed families (β = +0.17, p < .009) but is unrelated to later alcohol abuse in well-managed families (β = −0.01, ns). Figure 1 (left panel) illustrates the person × environment interaction predicting alcohol abuse at age 27. Predicted lines for age 27 alcohol abuse criteria (untransformed) are plotted for the effect of behavioral disinhibition in consistently poorly managed families and in consistently well-managed families, with all other model variables included at their mean values. The figure shows that behavioral disinhibition positively predicts age 27 alcohol abuse within poorly managed families but not within well-managed families.

Figure 1.

Interactions between behavioral disinhibition and family management in adolescence predicting alcohol abuse (left panel) and dependence (right panel) criteria at age 27.

Age 27 Alcohol Dependence

Table 4 presents the results of three nested regression models testing the hypotheses regarding the prediction of age 27 alcohol dependence. As with alcohol abuse, first, sociodemographic control measures of ethnicity, poverty, gender and early drinking (age 12) are included in Model 1. This model shows that gender and age 12 drinking each uniquely predict age 27 alcohol dependence. Model 2 then examines the main effects of the individual difference and family environment measures on later alcohol dependence criteria, controlling for the sociodemographic and early drinking measures in Model 1. As with alcohol abuse, results show that only behavioral disinhibition still marginally predicts alcohol dependence at age 27 (β = +0.076, p < .09). Family management is no longer significant once ethnicity, poverty, gender and early drinking are controlled, with the drop to nonsignificance coming primarily from the inclusion of early drinking and somewhat from the inclusion of behavioral disinhibition (not tabled). Model 3 then examines the contribution of person × environment interactions in the prediction of age 27 dependence criteria. Results show a significant interaction between behavioral disinhibition and family management predicting alcohol dependence (β = −0.186 p < .012), with ethnicity, poverty, gender, early drinking, and the main effects of behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition and family management in the model. In contrast, neither behavioral inhibition as a main effect nor in its interaction with family management significantly predicts age 27 alcohol dependence.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression analyses predicting alcohol dependence at age 27.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| 1 African Americana | −0.073 | 0.109 | −0.075 | 0.100 | −0.072 | 0.116 |

| 2 Asian Americana | −0.006 | 0.894 | −0.002 | 0.958 | 0.009 | 0.847 |

| 3 Poverty - Ages 10–13 | −0.050 | 0.250 | −0.054 | 0.218 | −0.060 | 0.167 |

| 4 Male | 0.253 | 0.001 | 0.234 | 0.001 | 0.236 | 0.001 |

| 5 Past-month Drinking Age 12 | 0.097 | 0.044 | 0.064 | 0.208 | 0.059 | 0.246 |

| 5 Behavioral Disinhibition (BDI) - Age 14–15 | 0.076 | 0.092 | 0.146 | 0.011 | ||

| 6 Behavioral Inhibition/Anxiety (BI/A) - Age 14–15 | 0.008 | 0.837 | 0.040 | 0.480 | ||

| 7 Family Management - Age 11–14 | −0.041 | 0.327 | 0.231 | 0.250 | ||

| 8 BDI × Family Management | −0.186 | 0.060 | ||||

| 9 BI/A × Family Management | −0.104 | 0.553 | ||||

| R2 | 8.9% | 0.001 b | 9.5% | 0.861 b | 10.0 % | 0.035 b |

= vs. Caucasian;

= Significance of change in R2.

Regression models including ethnicity, poverty, gender, early drinking, and the main effects of behavioral disinhibition and behavioral inhibition were conducted within the two family management groups. These analyses found that behavioral disinhibition significantly predicts age 27 alcohol dependence within poorly managed families (β = +0.13, p < .05), but is unrelated to later alcohol dependence in well-managed families (β = +0.03, ns). Figure 1 (right panel) illustrates the person × environment interaction predicting alcohol dependence at age 27.

4. Discussion

Prior studies have found behavioral disinhibition to be predictive of adult alcohol abuse and dependence, and the present study replicates those findings. However, this study finds that the effects of behavioral disinhibition in adolescence on alcohol abuse and dependence criteria at age 27 depend on the quality of family management during adolescence. Youths high in behavioral disinhibition are at increased risk for later alcohol abuse and dependence if they are in consistently poorly managed family environments during adolescence. However, in consistently well-managed families, higher levels of behavioral disinhibition do not increase risk for later alcohol abuse and dependence in this sample.

Prior research has produced inconsistent results regarding the longitudinal relationship between behavioral inhibition and later alcohol problems. The present study finds no evidence that behavioral inhibition/anxiety in adolescence predicts adult alcohol abuse or dependence.

Family management practices at ages 11–14 predict both alcohol abuse and dependence at age 27. However, these relationships are reduced to nonsignificance once drinking at age 12 is included in analyses. The zero-order correlations in Table 1 show that good family management is associated with both less early drinking and less behavioral disinhibition in this sample. Using the method of growth mixture modeling to identify environmental trajectories from age 11–14 suggested that by age 11, most (86%) of the families were already in either stable high (43%) or stable low (43%) family management trajectories. It is possible that good family management reduced the likelihood of early drinking, which has been shown to be predictive of alcohol use disorder in adulthood. These findings also support early preventive intervention efforts to develop good family management practices before the transition to adolescence.

This study has limitations. Some of predictor variables, including behavioral disinhibition, behavioral inhibition and family management are included at the same time period. While it is possible that environment (family management) affects the observed individual characteristic of disinhibition, research suggests that behavioral disinhibition is highly heritable (A2 = 0.84), and is not influenced significantly by shared environmental factors (Iacono et al., 2008; Young et al., 2000). Second, data are derived from self-reports during face-to-face interviews. While self-report measures carry potential for bias due to socially desirable responding, much has been learned through self-reported information related to substance use (Richter and Johnson, 2001). Validation studies suggest that self-reports of substance use in the past year or the past month are accurate (Harrison, 1997). Steps to reduce response bias in this study include interviews conducted in a private location, the use of coded response showcards, and two-decade long relationships of trust established with study participants. Strengths of the study include prospective (rather than retrospective) longitudinal assessment of predictors and outcomes and use of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule to determine indicators of diagnosable disorders.

The present findings showing that behavioral disinhibition has effects on later indicators of alcohol abuse and dependence in poorly managed families, but not in well-managed families, suggest that studies seeking to examine the role of genetic factors in the development of alcohol abuse and dependence should consider environmental factors as moderators of these effects. It is necessary to investigate the moderating effects of environmental factors such as family management practices in order to accurately understand the contribution of individual genetic factors to alcohol abuse and dependence.

The present findings are consistent with findings reported by Grekin & Sher (2006) and Grucza and colleagues (2006) that the effects of behavioral disinhibition were exacerbated by an alcohol risk environment. In both studies, however, behavioral disinhibition predicted increased risk of alcohol dependence even among those not in alcohol risk environments. The present study finds that in consistently well-managed families during adolescence, there is no relationship between a child’s behavioral disinhibition and later alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms. This suggests that if parents of dispositionally undercontrolled adolescents practice good family management during adolescence, they can reduce the likelihood that these adolescents will develop alcohol problems in adulthood. Even in the presence of individual risk for alcohol problems, interventions focused on strengthening the family environment during adolescence may have important preventive effects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Ratings of relations between DSM-IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6–18, TRF, and YSR. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Noble EP, Sheridan PJ, Montgomery A, Ritchie T, Jagadeeswaran P, Nogami H, Briggs AH, Cohn JB. Allelic association of human dopamine D2 receptor gene in alcoholism. JAMA. 1990;263:2055–2060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, Sayette M. Anxiety and the development of alcoholism. American Journal of Addiction. 1993;2:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB. The natural history of adolescent alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2004;99:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Neighbors BD, Lesnick LA, Lynch KG, Donovan JE. Family functioning and adolescent alcohol use disorders. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. Reinforcement sensitivity theory and personality. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2004;28:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Bierut L, Hinrichs A, Fox L, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Hesselbrock V, Schuckit M, Almasy L, Tischfield J, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Nurnberger J, Jr, Xuei X, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T. The role of GABRA2 in risk for conduct disorder and alcohol and drug dependence across developmental stages. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:577–590. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, Goate A, Kuperman S, Schuckit M, Crowe R, Smith TL, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Foroud T. Association of GABRG3 with alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:4–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000108645.54345.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, Tian H, Almasy L, Bauer LO, Crowe RR, Goate A, Hesselbrock V, Jones K, Kwon J, Li TK, Nurnberger JI, Jr, O’Connor SJ, Reich T, Rice J, Schuckit MA, Porjesz B, Foroud T, Begleiter H. Variations in GABRA2, encoding the alpha 2 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:705–714. doi: 10.1086/383283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley TC, Sugden K, Corsico A, Gregory AM, Sham P, McGuffin P, Plomin R, Craig IW. Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:908–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch M-A, Schwartz L, Albaugh B, Virkkunen M, Goldman D. Dimensional anxiety mediates linkage of GABRA2 haplotypes with alcoholism. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2006;141B:599–607. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of drug and alcohol problems: A longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken IHA, Muris TP, Georgieva I. Gray’s model of personality and addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, Gould TD. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:636–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzer D, Levitan RD, Sheldon T, Toneatto T, Rector NA, Goering P. Lifetime rates of alcoholism in adults with anxiety, depression or co-morbid depression/anxiety: a community survey of Ontario. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;79:209–15. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commentary. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987a;21:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1987b. [Google Scholar]

- Grekin E, Sher KJ. Alcohol dependence symptoms among college freshmen: Prevalence, stability, and person–environment interactions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:329–338. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza R, Cloninger C, Bucholz K, Constantino J, Schuckit M, Dick D, Bierut L. Novelty Seeking as a Moderator of Familial Risk for Alcohol Dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2006;30:1176–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:754–762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L. The validity of self-reported drug use in survey research: An overview and critique of research methods. In: Harrison L, Hughes A, editors. NIDA Research Monograph: Vol. 167. Validity of self-reported drug use: Improving the accuracy of survey estimates. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1997. pp. 17–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Nunes E. Cormorbidity of alcohol, drug and psychiatric disorders: epidemiology. In: Kranzler H, Rounsaville B, editors. Dual diagnosis and treatment: Substance abuse and comorbid medical and psychiatric disorders. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A categorical or dimensional phenotype. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:226–234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance-abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott RD, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:280–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Chung I-J, Nagin DS. Developmental trajectories of family management and risk for violent behavior in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EM, Stoltenberg SF, Bullard KH, Li S, Zucker RA, Burmeister M. Antisocial alcoholism and serotonin-related polymorphisms: Association tests. Psychiatric Genetics. 2002;12:143–153. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, White HR, Chung I-J, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:892–901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–46. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer CJ, Timberlake D, Haberstick BC, Lessem JM, Ehringer MA, Smolen A, Hewitt JK. Genetic influences on quantity of alcohol consumed by adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Kivlahan D, Walker RD. Cloninger’s tridimensional theory of personality and psychopathology: Applications to substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:48–66. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono W, Malone S, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Turner RJ, Iwata N. BIS/BAS levels and psychiatric disorder: An epidemiological study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Korten AE, Rodgers B. Using the BIS/BAS scales to measure behavioral inhibition and behavioral activation—factor structure, validity and norms in a large community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kambouropoulos N, Staiger PK. Personality, behavioural and affective characteristics of hazardous drinkers. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Convergence in prospective longitudinal surveys of drug use in normal populations. In: Kandel DB, editor. Longitudinal research on drug use: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Hemisphere-Wiley; Washington, DC: 1978. pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, Albanese MJ. Understanding addiction as self medication: Finding hope behind the pain. Rowman & Littlefield; Lanham, MD US: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Nelson-Gray RO, Mitchell JT. Reinforcement sensitivity and maternal style as predictors of psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:1139–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev GG. Behavioural activation as predictor of substance use: mediating and moderating role of attitudes and social relationships. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, Boutrel B, Chen SA, Kenny PJ, Markou A, O’Dell LE, Parsons LH, Sanna PP. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;27:739–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, La Forge KS. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moal M, Koob GF. Drug addiction: Pathways to the disease and pathophysiological perspectives. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;17:377–393. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux S, Miller P, Choquet M, Plant M. Family structure, parent-child relationships, and alcohol and other drug use among teenagers in France and the United Kingdom. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2002;37:52–60. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA, Friedrich WN, Fisher J. Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children’s symptomatology: Expert ratings and confirmatory factor analyses of the CBCL. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:683–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limosin F, Loze JY, Dubertret C, Gouya L, Ades J, Rouillon F, Gorwood P. Impulsiveness as the intermediate link between the dopamine receptor D2 gene and alcohol dependence. Psychiatric Genetics. 2003;13:127–129. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000066963.66429.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton NJ, Dawe S. Alcohol abuse and dysfunctional eating in adolescent girls: The influence of individual differences in sensitivity to reward and punishment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:455–462. doi: 10.1002/eat.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Kosterman R, Mason WA, McCauley E, Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl TI, Lengua L. Longitudinal associations among obesity, alcohol use disorders, and depression in young adulthood. General Hospital Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.013. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: II. Alcoholism versus drug use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:394–404. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Taylor J, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: I. Effects of gender and alcoholism subtype. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behaviors: evidence from behavioral-genetic research. Adv Genet. 2005;55:41–104. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)55003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus: statistical analysis with latent variables: user’s guide. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based method. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM. Understanding the roles of genome and envirome: methods in genetic epidemiology. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;40:s12–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. Psychosocial processes and mechanisms of risk and protection. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28:143–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RM, Colder CR. Predicting alcohol patterns in first-year college students through motivational systems and reasons for drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:10–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani K, Ujike H, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Katsu T, Nomura A, Uchida N, Hamamura T, Fujiwara Y, Kuroda S. The GABA type A receptor alpha5 subunit gene is associated with bipolar 1 disorder. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;381:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Lynam D. Neurocognitive Impairments in boys on the life-course persistent antisocial path. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:38–49. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM. The interplay of genetic influences and social processes in developmental theory: specific mechanisms are coming into view. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:357–74. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Johnson PB. Current methods of assessing substance use: A review of strengths, problems, and developments. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31:809–832. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Washington University, Department of Psychiatry; St. Louis, MO: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:226–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. Alcohol Dependence and Anxiety Disorders: What Is the Relationship? Focus. 2004;2:440–453. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Wood MD. Personality and substance use disorders: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Personality and the genetic risk for alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Willard A, Hromi A. Mood and alcohol consumption: An experience sampling test of the self-medication hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Moss HB, Gioio AE, Hughes HB, Kaplan BB, Tarter RE. An association between a microsatellite polymorphism at the DRD5 gene and the liability to substance abuse: Pilot study. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:75–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1021463722326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:269–77. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Krauter KS, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibition. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;96:684–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisserson RN, Palfai TP. Behavioral Activation System (BAS) sensitivity and reactivity to alcohol cues among hazardous drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2178–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Alcohol use and the alcohol use disorders: A developmental-biopsychosocial systems formulation covering the life course. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 620–656. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: what have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103:100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]