Abstract

The adult heart contains reservoirs of progenitor cells that express embryonic and stem cell-related antigens. While these antigenically-purified cells are promising candidates for autologous cell therapy, clinical application is hampered by their limited abundance and tedious isolation methods. Methods that involve an intermediate cardiosphere-forming step have proven successful and are being tested clinically, but it is unclear whether the cardiosphere step is necessary. Accordingly, we investigated the molecular profile and functional benefit of cells that spontaneously emigrate from cardiac tissue in primary culture. Adult Wistar-Kyoto rat hearts were minced, digested and cultured as separate anatomical regions. Loosely-adherent cells that surround the plated tissue were harvested weekly for a total of five harvests. Genetic lineage tracing demonstrated that a small proportion of the direct outgrowth from cardiac samples originates from myocardial cells. This outgrowth contains sub-populations of cells expressing embryonic (SSEA-1) and stem cell-related antigens (c-Kit, abcg2) that varied with time in culture but not with the cardiac chamber of origin. This direct outgrowth, and its expanded progeny, underwent marked in vitro angiogenic/cardiogenic differentiation and cytokine secretion (IGF-1, VGEF). In vivo effects included long-term functional benefits as gauged by MRI following cell injection in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Outgrowth cells afforded equivalent functional benefits to cardiosphere-derived cells, which require more processing steps to manufacture. These results provide the basis for a simplified and efficient process to generate autologous cardiac progenitor cells (and mesenchymal supporting cells) to augment clinically-relevant approaches for myocardial repair.

Keywords: cell therapy, myocardial infarction, cardiac regeneration, angiogenesis, ventricular remodelling

1.0 Introduction

Historically, the post-natal heart has been viewed as an organ incapable of regeneration. This conclusion was based upon early evidence that cardiogenesis is completed soon after birth.[1, 2] However, this dogma has been challenged by evidence that cardiomyocyte replacement occurs throughout adulthood [3, 4] and by recognition of the existence of adult heart progenitor cells expressing embryonic (SSEA-1) and/or stem cell-related (abcg2, c-Kit, isl-1, sca-1) antigens.[5, 6] Furthermore, several studies have shown that isolated and purified populations of these cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) are capable of differentiating into cardiac tissue and improving function after a myocardial injury.[5, 6]

With a view to providing patient-specific therapy, efficient and rapid methods for CPC isolation are highly desirable. Neural stem cells can be expanded from tissue as self-assembling spherical aggregates (“neurospheres”).[7] This technology was applied to the heart to produce spherical progenitor-rich aggregates of cardiac cells, termed cardiospheres.[8, 9] Our group advanced this method towards clinical translation by the expansion of cells from human endomyocardial biopsies with an intermediate cardiosphere-forming step to generate cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs).[10, 11] The rationale for this cardiosphere formation step was to enrich in “stemness”, but it is unknown whether this step is actually required. Other groups have employed techniques based on allowing cells to proliferate from the initial sample of cardiac tissue, with positive candidate cell selection (e.g., SSEA-1+, c-Kit+, sca-1+) prior to further ex vivo proliferation of these defined subpopulations.[6, 12, 13] As with cardiospheres, these initially homogenous sub-populations have been shown to contain clonogenic and multipotent cells capable of self-renewal.

This study investigates the ultimate simplification of these culture techniques by focusing on the primary product, that is, the initial cellular outgrowth from cardiac samples without recourse to antigenic sub-selection or cardiosphere expansion. This approach is attractive as it would improve production efficiency, limit prospects of culture-acquired phenotypic drift and, as has been demonstrated in mesenchymal stem cells, the risk of cancerous transformation.[14] Accordingly, we profile the regional and temporal patterns of growth, differentiation and gene expression of CPCs cultured directly from myocardial tissue. Additionally, we provide translational relevance by examining the capacity for functional differentiation and post MI functional improvement as compared to those expanded as CDCs.

2.0 Materials and methods

2.1 Cell Culture

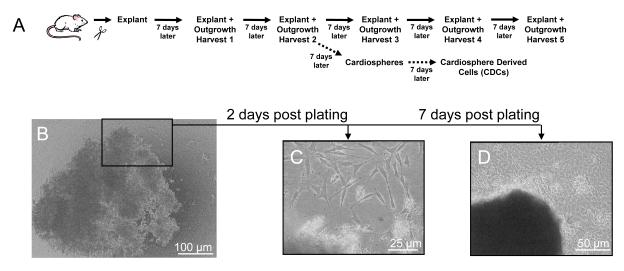

Cardiac progenitor cells were cultured from the hearts of adult male Wistar-Kyoto rats (WK; 3.0±0.4 months old) as previously described.[10] In brief, hearts were excised from heparinized rats (1000 U IV) and underwent retrograde perfusion with heparinized PBS to minimize thrombus formation. The heart was then dissected into five different regions (atria, LV-free wall, RV-free wall, septum apex, septum base) and each region was separately cut into fragments less than 1 mm3, washed and partially digested with collagenase (1 mg/ml). These tissue fragments (termed cardiac explants; Fig. 1a and 1b) were cultured on fibronectin (20 μg/ml) coated dishes in cardiac explant media (CEM; Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium, 20% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mmol/l L-glutamine, and 0.1 mmol/l 2-mercaptoethanol). During the first week of growth, a layer of fibroblast-like cells emerge from the cardiac explant (Fig. 1c) above which loosely-adherent cells later become suspended (Fig. 1d). The cells surrounding the explant (termed cardiac outgrowth) were harvested using mild enzymatic digestion (0.05% trypsin). Cardiac outgrowth could be harvested up to four more times from the same specimen (Fig. 1a). For experiments utilizing CDCs, cardiac outgrowth was seeded at 2×104 cells/ml on poly-D-lysine coated dishes in cardiosphere growing media (CGM; 35% IMDM/65% DMEM-Ham’s F-12, 2% B27, 0.1 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 ng/ml EGF, 20 ng/ml bFGF, 40 nmol/L Cardiotrophin-1, 40 nmol/L thrombin, 100 U/ml pen-strep, 2 mmol/l L-glutamine). Cells that remained adherent to the poly-D-lysine coated dishes were discarded, while detached cardiospheres were plated on fibronectin coated flasks and expanded as monolayers to generate CDCs. Single cells were counted under phase microscopy to track cell growth for each specimen and region.

Figure 1. Specimen processing for cardiac outgrowth, cardiosphere and cardiosphere derived cell (CDC) expansion.

(A) Schematic depiction of the steps involved from tissue harvest and through serial collection of cardiac outgrowth from the plated tissue (referred to as the explant). (B) Example tissue explant immediately following plating. (C) Magnified view of the same tissue explant 2 days later and (D) loosely-adherent cells 7 days after plating.

WK rat dermal fibroblasts served as a negative live-cell control and were cultured as described.[15] Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were used in co-culture experiments and were cultured as described.[16, 17]

The colorimeric WST-8 assay (Cell counting kit 8, Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. Gaithersburg, MD) was used to track CDC, outgrowth and dermal fibroblast proliferation. Population doubling was calculated with first colorimetric assay as the starting population [# of population doublings = log2(cell number)]. Doubling time was calculated as the difference between the time(t) and cell counts(N) of the starting population(1) and the final population after two weeks in culture(2) [Doubling time = (t2-t1)log2/(logN2-logN1)].[18]

2.2 Genetic cell fate mapping with bi-transgenic MerCreMer-Z/EG mouse cardiomyocytes

Bi-transgenic MerCreMer-Z/EG mice were produced by crossbreeding cardiomyocyte-specific MerCreMer mice [19] and Z/EG mice [20] (Jackson Laboratory) as described previously.[21] The Z/EG reporter mouse carries cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer/chicken b-actin promoter driving floxed b-galactosidase and multiple stop codons, followed by eGFP. Animal genotype was verified by standard PCR on tail genomic DNA using the following primers: MerCreMer forward: 5′-ATACCGGAGATCATGCAAGC-3′; MerCreMer backward: 5′- AGGTGGACCTGATCATGGAG-3′; and ZEG forward: 5′- ACGGCAAGCTGACCCTGAAG-3′; ZEG backward: 5′- AAGATGGTGCGCTCCTGGAC-3′; internal control forward : 5′- CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3′; and internal control backward: 5′- GGATGATGCTAGAATTTCCACCTAC-3′. Double heterozygous bi-transgenic MerCreMer-Z/EG mice were used for the myocyte lineage tracing experiments after induction of Cre recombination for GFP labeling exclusively in cardiomyocytes by 4-OH-Tamoxifen treatment.[21] Tamoxifen-treated bi-transgenic mice were used at the age of 6-10 week and we did not see significant difference in their capability of cell outgrowth. Bi-transgenic hearts underwent the same cell culture as WK rats on 2-well chamber slides with immunostaining and microscopy performed 1 week after plating.

2.3 PCR Analysis

Screening for markers of CPC or cardiac identity was performed using RT PCR. One million outgrowth cells were pooled from 4 to 6 separate cultures at the same harvest time point and anatomical region. RNA was extracted treated with DNase and cDNA was synthesized. Gene-specific primers were designed were chosen using GeneRunner (v 3.05; sequences available on request).

2.4 Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry experiments were performed using a benchtop flow cytometer (LSRII; BD Biosciences, San Jose, Ca). Monoclonal antibodies were labelled with fluorophores using commercial kits as required (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The following monoclonal antibodies and conjugated fluorochromes were used with corresponding isotype controls: AA4 (BD Pharmigen, San Jose, Ca), abcg2-a488 (sc-25822, Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, Ca), CD3 (MCA772FB, AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), CD11b (MCA275FB, AbD Serotec), CD31 (sc-28188, Santa Cruz Biotech), CD45 (MCA340FB, AbD Serotec), CD133 (sc-30220, Santa Cruz Biotech), c-Kit-a647 (sc-168, Santa Cruz Biotech), isl-1 (sc-30200, Santa Cruz Biotech), Ox-62 (MCA1029G, AbD Serotec), sca-1 (AF1226, RD Systems, Mn) and SSEA-1-PE (sc-21702, Santa Cruz Biotech). A minimum of 60,000 events were collected. Fluorescent compensation was performed using single labelled controls. The percentage of positive cells was defined as the percent of the population falling above the 99th percentile of an isotype-matched antibody control cell population. All measures were performed using Flow-Jo (v. 7.2.2 Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

2.5 Vector Production and Cell Transduction

The lentiviral viral vectors (pRRLsin18.cPPT.LacZ.WPRE and pRRLsin18.cPPT.NCX1.luc.WPRE) were prepared as described.[10, 22] Briefly, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with a four plasmid vector system using lipofectamine 2000. Twenty four and forty eight hours later, the vector suspension was collected and concentrated using Centricon Plus-70 filter columns (100.000 MWCO; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Vector titers were determined using serial vector dilutions in 293T cells or enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA)-based assays (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) for the LacZ and NCX1-luc vectors, respectively. Based on transgene expression, transduction efficiencies of 80-90% were achieved after 12 hours of incubation with the LacZ and NCX1-luc vectors in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml) at MOI of 20 or 35, respectively.

2.6 Immunohistochemistry, Immunostaining and Microscopy

For cell labelling, explants were cultured directly on fibronectin coated glass coverslides and when stromal outgrowth had surrounded the explant, the coverslip was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained in the whole mount. For tissue labelling, rat hearts were excised, frozen and sectioned in 10μm slices. Secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa fluorochromes were used. For light microscopy, tissue sections from all rats were stained with Masson’s trichrome. Tissue viability within the infarct zone was calculated from Masson’s trichrome–stained sections by tracing the infarct borders manually and then using ImageJ software to calculate the percent of viable myocardium within the overall infarcted area (number of red pixels divided by total number of pixels). Six sections were analyzed per animal and averaged.

2.7 In-vitro differentiation

2.7.1 Cardiogenic differentiation

NRVMs were processed and plated in NRVM media (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep) at densities of 125,000 cells/cm2 on fibronectin coated 24 well co-culture plates (3470, 6.5 mm diameter, 0.4 μm pore size; Corning Transwell, Corning, NY). NRVMs for direct co-culture were plated on the well surface whereas NRVMs for indirect co-culture were plated into the co-culture mesh basket. Twenty four hours later, CDCs, cardiac outgrowth and dermal fibroblasts were transduced with the NCX1-luc vector in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene and plated onto fibronectin coated plasticware. Sixteen hours later, the cells were harvested and replated in cardiogenic media at densities of 20,000 cells/cm2 either in direct or indirect contact with NRVMs. Cardiogenic media consisted of DMEM-LG, 40% MCDB-201, 0.75% dimethylsulfoxide, 0.1% 10 mmol/l L-ascorbic acid, 0.01% ITS liquid media supplement, 0.01% linoleic acid-albumin, 0.01% Pen-Strep, 0.0002% 0.25 mmol/l dexamethasone, 0.001% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse fibroblast growth factor 8b, 100 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor 4, 10 ng/ml recombinant human protein rhDKK-1 and 10 ng/ml recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2.[6]

Seven days after lentiviral transduction and NRVM co-culture, the cardiac differentiation of CDCs, outgrowth and dermal fibroblasts within the co-culture system was assessed by in-vitro bioluminescence imaging. For in-vitro imaging, the NRVM transwell inserts were removed and D-Luciferin (Gold Biotechnology, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was added to the wells before placing the 24 well plate into the IVIS 200 Xenogen Imaging System (Xenogen Corporation, Alameda, CA). For visualization purposes, the luminescent image (exposure time 1 min; high sensitivity) was overlaid onto the photographic image. The signal intensity is represented by radiance (p/s/cm2/sr) and is encoded by pseudocolors on the luminescent image. Following in-vitro imaging, the cells were harvested and underwent confirmatory bioluminescence imaging or real time PCR for markers of the lentiviral transcript. As previously described, the in-vitro luciferase assay involves homogenizing the cells in lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) followed by centrifugation and luminometry of the supernatant in the presence of Luciferin.[23] Activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU) normalized to the real time PCR abundance of the lentiviral transcript.

2.7.2 Angiogenic differentiation

Angiogenic potential was assessed by plating CDCs and cardiac outgrowth in a 96-well plate endothelial tube formation assay (ECM625, Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Dermal fibroblasts and HUVECs (Lonza, Walkerville, Md) served as negative and positive controls, respectively. For analysis, CDCs, outgrowth and dermal fibroblasts were plated at 10,000 cells/well and imaged 4 hours post plating. As per manufacturer’s instructions, HUVECs were plated at 20,000 cells/well and imaged at 18 hours post plating. Tube formation was analyzed by manually measuring the total tube length within 6 well random fields for each sample (6 samples/cell type) at 10× magnification under phase microscopy.[24] Image J (1.38×, NIH) with the Neuron J plug-in was used to delineate the number of linear tubules identified and the cumulative tubule length.

2.8 ELISA

Cytokine secretion by CDCs and outgrowth was measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay using commercially available kits (RD Systems and Institute of Immunology, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, one million CDCs and cardiac outgrowth cells were plated on fibronectin coated T25 flasks in low FBS media (CEM with 2% FBS) for 48 hours. Conditioned media was then collected, filtered and stored at −80°C for later analysis. Supernatants were screened for HGF, IGF-1, PDGF, SDF-1 and VEGF using an ELISA system. All immunosorbent measures were normalized to media volume and protein content (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Ca).

2.9 Myocardial infarction, cell injection, and functional evaluation

Myocardial infarctions were created by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery of 8-9 week old WK rats, as previously described.[25] Cardiac outgrowth from the second harvest of explants (n=6 WK rats) was used in these studies. After harvest, outgrowth was transduced with lentiviral vector encoding LacZ for long term histological tracking. Following transduction, a portion of this outgrowth was transitioned to CDCs and used for subsequent in vivo cell injection after the first passage. Animals were injected with either 50 μl of PBS (n=6), or 50 μl of PBS containing 106 CDCs (n=8), outgrowth cells (n=8), or dermal fibroblasts (n=6) at two sites bordering the myocardial infarct (apex and LV free wall).

All rats underwent MRI before surgery (baseline) then 3 and 6 weeks after surgery. MRI assessment was done using a 9.4T Bruker horizontal bore spectrometer. Rats were anaesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane. High-resolution segmented MRI FLASH images were obtained to quantify left ventricular function (field of view: 64 × 64 mm; 2D matrix: 256 × 128; Echo time: 1.6 ms; Repetition Time: 10 ms; flip angle: 20). A set of multislice short-axis images (slice thickness 2 mm without gap between slices) for end-systole and end-diastole were acquired. Left ventricular end diastolic (LVEDV) and end systolic volumes (LVESV) were manually traced using the NIH ImageJ software (version 1.38×). Total LV volumes were calculated as the sum of all slice volumes. The left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated by the equation (LVEDV-LVESV)/LVEDV×100%). Regional improvement within the central scar was assessed by measuring left-ventricle wall thickening using averages obtained from the four most apical slices for each heart. Wall thickening was calculated as the relative difference in LV wall thickness in end-systole and end-diastole and expressed as a percentage of end-diastolic thickness.

Invasive hemodynamic measurements were performed 6 weeks after cell transplantation or saline injection. Under general anesthesia (isoflurane 1.5%), a 2 cm incision was made in the right neck, the right common carotid artery was dissected, and a pressure catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted. The catheter was advanced into the left ventricle, and pressure was recorded after an initial stabilization period with Acqknowledge (v 3.8.1, London, Ontario, Canada). After recording was completed, the catheter was removed and the heart was harvested for histological analysis. Hemodynamic tracings were analyzed for maximum dP/dt (+dP/dt), minimum dP/dt (−dP/dt) and left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP). To account for variations in preload and afterload, the maximal contractile element velocity (VPM; maximum value of (dP/dt)/P) was calculated.[26]

All functional evaluations were conducted and analyzed by investigators blinded to the animal’s treatment group.

2.10 Statistical analysis

All data is presented as mean ± SEM. To determine if differences existed within groups, data was analyzed by a one-way ANOVA; if such differences existed, Bonferroni’s corrected t-test was used to determine the group(s) with the difference(s) (G-B Stat software). A final value of P≤0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All probability values reported are 2-sided.

3.0 Results

3.1 Therapeutically-relevant quantities of cells can be grown from adult heart tissue

Initial growth of cells from explants was robust (Harvest 1: 1.2×107 cells/harvest) with production modestly reduced with prolonged time in primary culture (Harvest 5: 8.0×106 cells/harvest). A cumulative yield of 50±10 million cells was reproducibly achieved after a total of 35 days in culture from 548±90 mg of myocardial tissue. When the quantity of harvested cells was normalized to the amount of starting tissue, culture yield from the atria markedly exceeded other regions throughout the entire culture period. This difference is highlighted when contrasting the normalized cumulative atria culture yield (5.9×108 cells/g) to the culture yield of the second most prolific region (base of the septum; 1.9×108 cells/g; p<0.05). Following harvest and plating in cardiac explant media, the time required for a population of cardiac outgrowth cells to double was no different from CDCs and dermal fibroblast (cardiac outgrowth 118±3h, CDCs 115±5h and dermal fibroblasts 117±1h; n=8, p=ns).

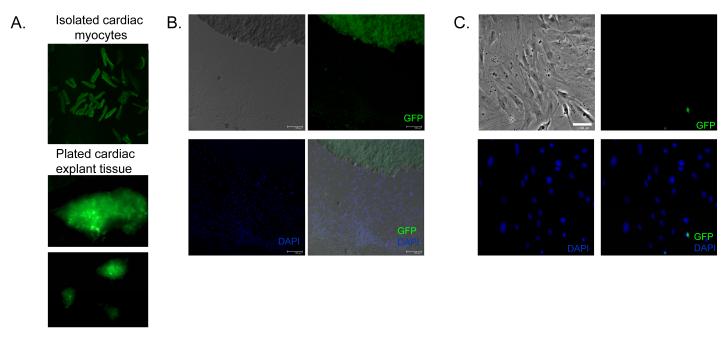

The origin of cardiac outgrowth cells is still unclear. To investigate this, we analyzed day 7 outgrowth from double heterozygous Mer-Cre-Mer-ZEG reporter mice. Only cells which are myocytes (or once were myocytes) are labelled with GFP+.[21] Using this model, we have found that, before and immediately following digestion, cells within the cardiac explant robustly express GFP (Fig. 2a). This finding indicates that many of the myocytes within the explant tissue survive to be plated on fibronectin-coated dishware. After one week in culture, only a small proportion of the outgrowth adherent to the dishes expresses GFP (6.9±0.9% in 5 random fields sampled from 6 separate cultures). Cells expressing GFP represented a greater proportion of the adherent outgrowth surrounding the plated tissue (14.5±4.3%; Fig. 2b) with reduced contribution farther from the tissue (6.5±2.5% ≥2 microscopic fields from the tissue; Fig. 2c). Five days post-plating, the number of GFP+ cells in outgrowth is negligible[9]; the data here show that only a small fraction of the direct outgrowth from myocardial biopsies arises from cells that were once myocytes by genetic lineage tracing; the majority likely arises from direct proliferation of resident cardiac stem and/or mesenchymal cell(s). Interestingly, the plated explant tissue no longer strongly expresses GFP, hinting that many of the myocytes within the explant have likely undergone apoptosis in culture.

Figure 2. Contribution of cardiomyocytes to the direct outgrowth from myocardial samples.

(A) Fluorescent imaging of cardiac myocytes and plated explant tissue (one hour after collagenase digestion) from transgenic mice with cardiomycytes expressing GFP under the control of myosin heavy chain driven tamoxifen-regulated Cre recombinase. (B) Indirect immunofluorescent staining of plated cardiac explant and outgrowth adjacent to the explant (within 1 microscopic field) after 1 week in culture. (C) Indirect immunofluorescent staining of cardiac outgrowth distal from the plated explant (> 2 microscopic fields) after 1 week in culture.

3.2 Cells grown directly from adult heart tissue possess genetic and surface markers of CPCs

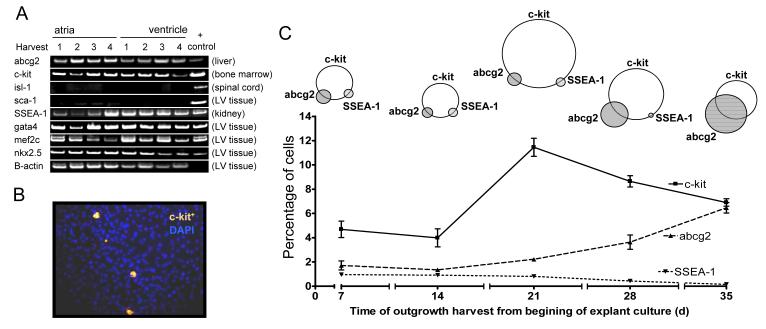

Reverse transcriptase PCR was used to screen collections of cardiac outgrowth pooled from different regions for markers of cardiac progenitor cells (abcg2, c-Kit, isl-1, sca-1, SSEA-1) and early cardiac lineage (GATA-4, MEF-2C, Nkx2.5). As shown in Fig. 3a, abcg2, c-Kit and SSEA-1 are present and persistent in the cardiac outgrowth. While sca-1 could be readily identified in the ventricle, it was not found within pooled samples of cardiac outgrowth. Isl-1 was not found the native heart or cardiac outgrowth despite being present in control spinal cord samples. Markers of early cardiac lineage (GATA-4, MEF-2C, Nkx2.5) were found in both cardiac outgrowth and samples of cardiac tissue. As shown in Fig. 3b, regions from which loosely-adherent cells emerge also stained positive for c-Kit alone or in combination with SSEA-1. Flow cytometry demonstrated two distinct sub-populations of CPCs defined by the presence of c-Kit co-expressing either abcg2 or SSEA-1. As shown in Fig. 3c, the proportion of c-Kit+ cells falling above the 99th percentile of the control peaked following the first two harvests (harvest 3: 12±1%) and then gradually declined with time in culture. The proportion of cells expressing markers of embryonic origin (SSEA-1) was small and peaked in the first harvest (1.0±0.1%) such that this sub-population was virtually undetectable by the final harvest. In contrast, the proportion of cells expressing markers of side population (abcg2+) cells increased with progressive time in culture (Harvest 5: 7±1%). The Venn diagrams graphically represent the relative co-segregation of these markers with representative dot plots provided in the data supplement (Figure S1). When the CPC sub-populations were analyzed based upon the region of plated tissue, there was no difference in the proportion c-Kit+, abcg2+ or SSEA-1+ cells (data not shown).

Figure 3. Molecular characterization of explant-derived cardiac outgrowth.

(A) Screening results of pooled regional collections of cardiac outgrowth cells using RT PCR for markers of cardiac progenitors (abcg2, c-Kit, sca-1, isl-1), embryonic stem cells (SSEA-1) and early cardiomyocyte markers (gata-4, MEF2C and nkx2.5) (n=3 to 5 culture samples pooled for 106 cells per group). (B) Indirect immunofluorescence staining for c-Kit of the first harvest cardiac outgrowth surrounding a section of plated atrial explant. (C) Flow cytometry of the temporal profile of serial collections of explant derived cardiac outgrowth for c-Kit and other antigenically distinct sub-populations (n=6 per group).

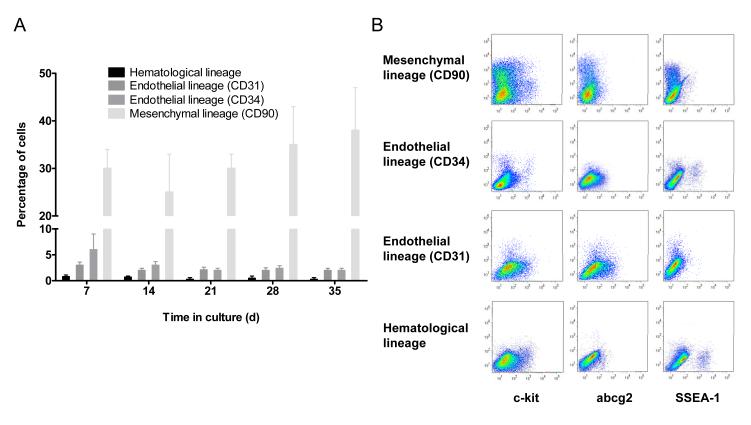

3.3 Direct outgrowth from cardiac samples contain sub-populations resembling endothelial and mesenchymal cells

As with studies examining human CDCs,[10] cardiac outgrowth contains significant sub-populations that phenotypically resemble mesenchymal or fibroblast cells (CD90+ Harvest 1: 30±4%, Fig. 4a). This sub-population remained constant throughout the time in culture. Cardiac outgrowth also contains small sub-populations with markers of endothelium (CD31+ +7 days in culture: 3.2±1.2%; CD34+ +7days in culture: 3.1±2.9%) and tended to decline with progressive time in culture (CD34+ +35 days in culture 2.4±0.3%, CD31+ +35 days in culture 2.2±0.5%; p=ns). Fig. 4b demonstrates minimal co-segregation between markers of CPC and the mesenchymal, endothelial and haematological lineage. Serial collections of cardiac outgrowth were negative for markers of other CPC populations (sca-1, isl-1), hematological origin (lin) and mast cell lineage (AA4+).

Figure 4. Flow cytometryic analysis of cardiac outgrowth cellular lineage.

(A) Proportion of cells detected by flow cytometry at each serial harvest expressing markers of endothelial (CD31, CD34), haematological (CD3, CD11b, CD45 and Ox-1) and mesenchymal (CD90) lineage (n=6 per group). (B) Flow cytometry dot plots demonstrating co-segregation of CPC (abcg2, c-Kit and SSEA-1) with lineage markers.

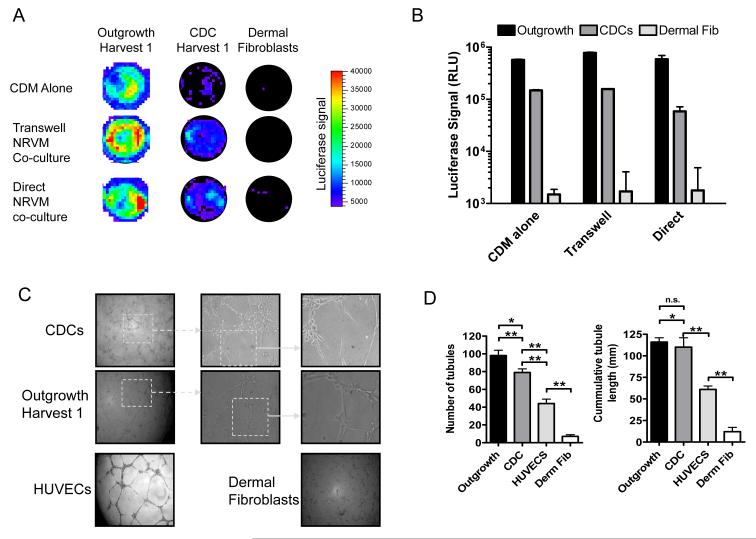

3.4 Direct outgrowth from cardiac samples differentiate into a cardiac phenotype

The propensity of cardiac outgrowth, CDCs and dermal fibroblasts to differentiate into myocardium were assessed using bioluminescent imaging of NCX1-driven luciferase expression following culture in conditions known to favour cardiac differentiation.[6, 23] As shown in Fig. 5a, in vitro bioluminescent imaging shows that NCX1 expression is markedly elevated in cardiac outgrowth as compared to both CDC and dermal fibroblasts. Also manifest is the salutary effect of direct and indirect NRVM co-culture. Fig 5b contrasts the luciferase activity of transduced cell lysates and confirms that cardiac outgrowth differentiates to a greater extent into myocardial precursors than CDCs (p<0.05, n=6). Cardiac outgrowth grown in basal differentiation media failed to manifest the NCX1 cardiac phenotype while proliferation in CDM media was similar between the three cell types assayed (data not shown). Although NRVM co-culture may imperfectly model true cardiomyogenicity,[27] this in vitro assay provides an expedient technique to extend prior work[6, 9, 10, 12, 13] and to compare directly the ability of outgrowth and derived progeny to differentiate into cardiomyocytes.

Figure 5. In vitro differentiation of cardiac outgrowth and CDCs.

(A) Representative bioluminescence images of cardiac outgrowth, CDCs and dermal fibroblast cells transduced with NCX1-luc and cultured in cardiomyocyte differentiation media (CDM) alone, in trans-well co-culture separated from NRVMs or directly in co-culture with NRVMs. (B) Group bioluminescence data from cardiac outgrowth, CDCs and dermal fibroblasts (n=6 per group). (C) Representative images of matrigel mediated tube formation for cardiac outgrowth, CDCs, HUVEC and dermal fibroblasts. (D) Analysis of tube formation (number of tubes and cumulative tube length) for cardiac outgrowth, CDCs, HUVEC and dermal fibroblasts (n=6 per group).

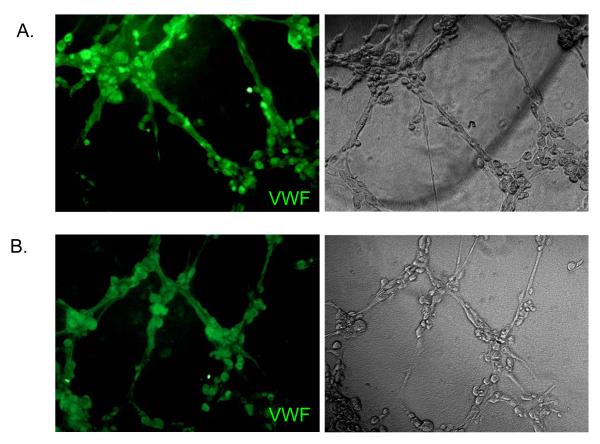

3.5 Direct outgrowth from cardiac samples forms tubules in an endothelial matrigel assay

To investigate the angiogenic capacity of cardiac outgrowth, we measured tubule network formation in a matrigel assay. Within 4 hours of plating on the gel substrate, cardiac outgrowth and CDCs formed tube-like networks akin to those made by HUVECs (Fig. 5c). As an indicator of in vitro angiogenesis, we quantified the number and cumulative length of tubes at the time of maximal tubule formation. As shown in Figure 5d, the cardiac outgrowth and CDC networks are characterized by multiple tubules of equivalent cumulative length. Thus, cardiac outgrowth and CDCs have a capacity to self-organize into vessel-like structures in vitro when subjected to endothelial differentiation conditions. Interestingly, both CDCs and cardiac outgrowth form robust tubular networks more rapidly than do HUVECs (4 vs. 18 hours, respectively) suggesting that these cells are markedly angiogenic. Analysis of the tubules formed by cardiac outgrowth and CDCs demonstrated endothelial markers (i.e., vWF) reminiscent of tubules formed using HUVECs (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Portions of the tubule structures formed by cardiac outgrowth and CDCs demonstrate endothelial markers.

Indirect immunofluorescence of the tubule structures formed by cardiac outgrowth (A) and CDCs (B) stained positive for Von Willebrands Factor.

3.6 Direct outgrowth from cardiac samples secretes cardioprotective and angiogenic cytokines

To explore the potential of cardiac outgrowth to secrete cytokines with cardioprotective, mitogenic and pro-angiogenic effects, conditioned media was screened using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the presence of HGF, IGF-1, PDGF, SDF-1 and VEGF. Cardiac outgrowth and CDCs secreted VEGF to an equivalent degree (1.8±0.2 vs. 2.0±0.3 pg/μg of protein lysate, p=ns). In contrast, the growth-stimulant IGF-1 was greater in cardiac outgrowth than CDCs (0.7±0.1 vs. 0.3±0.1 pg/μg of protein lysate, p<0.01). HGF and PDGF were not detected while SDF-1 was variably expressed to a minor degree in both cardiac outgrowth and CDCs (range 0-0.06 pg/μg).

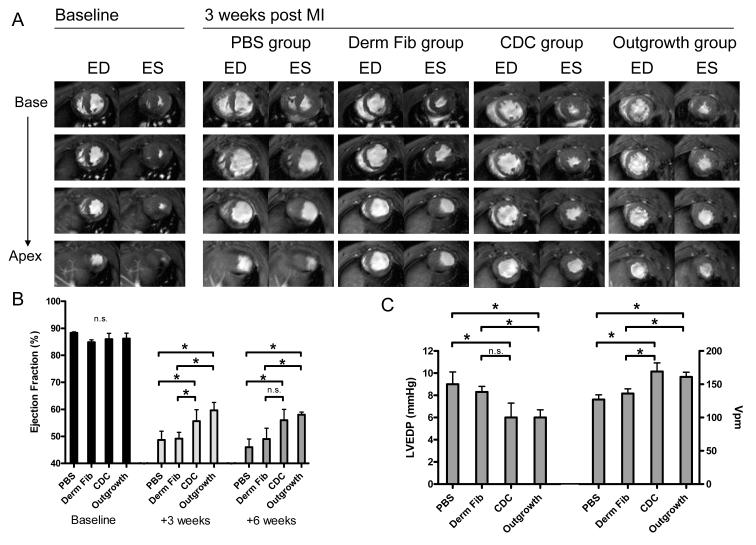

3.7 Injection of direct outgrowth from cardiac samples and expanded progeny improves ventricular function after LAD ligation

As shown in Fig. 7a, hearts treated with cardiac outgrowth and CDCs exhibited reduced ventricular dilation and greater systolic thickening 3 weeks after myocardial infarction. Fig. 7b illustrates this observation as animals injected with cardiac outgrowth or CDCs had a greater ejection fraction at 3 weeks (58±2% and 56±4%, respectively) than animals injected with dermal fibroblasts or PBS (49±4% and 46±3%, respectively). This difference in ejection fraction was maintained at the 6 week follow-up imaging. Left ventricular thickening in the central infarct region measured 3 weeks post myocardial infarction tended to be greater in the cardiac outgrowth and CDC groups (38±7% and 30±9%, respectively) than the dermal fibroblast and placebo groups (21±8% and 24±10%, respectively), but the differences did not attain significance. As shown in Fig. 7c, animals injected with cardiac outgrowth or CDCs had lower left ventricular end diastolic pressure (6.0±0.7 and 6.1±1.3 mm Hg, respectively) and greater maximal contractile element velocity (169±13 and 161±7 s−1, respectively) as compared to animals treated with dermal fibroblast or PBS.

Figure 7. Functional effects of cardiac outgrowth and CDCs on post MI ventricular function.

(A) Representative short axis cardiac MRI views at baseline and 3 weeks post MI. Images are displayed from base to apex (top to bottom) at end diastole (ED) and end systole (ES) for each study group. (B) Effect of PBS, dermal fibroblasts (Derm Fib), CDCs and cardiac outgrowth upon left ventricular ejection fraction at 3 and 6 weeks by MRI imaging (n=6-8 per group). (C) Effect of PBS, dermal fibroblasts, CDCs and cardiac outgrowth upon myocardial hemodynamics (left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and contractility (instantaneous pressure Vpm)) at 6 weeks (n=4-6 per group). Differences between groups were not statistically significant (n.s.). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

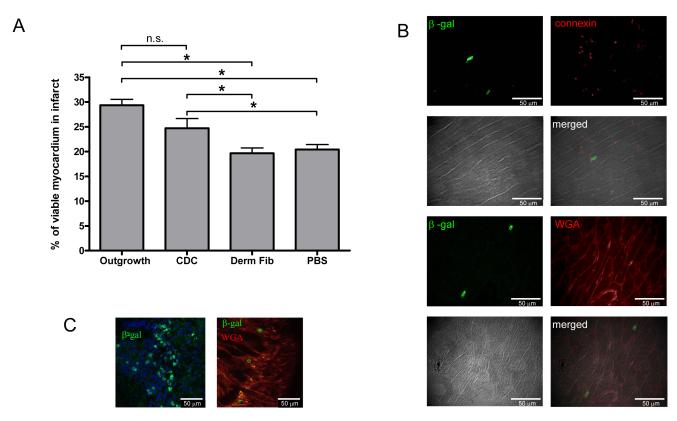

3.8 Treatment with the direct outgrowth from cardiac samples limits infarct size

To quantify the ability of injected cells to regenerate heart muscle within the infarcted region, sections were stained with Masson’s trichome to differentiate between viable tissue (red) and fibrous tissue (blue). The overall infarct area, as defined by the boundaries of the scarred area, did not differ between treatment and placebo groups (cardiac outgrowth 27±4%, CDCs 26±6%, dermal fibroblasts 27±4% and PBS 20±8%, p=ns). Nevertheless, there was a greater amount of viable tissue within the infarct regions in both the cardiac outgrowth and CDC groups as compared to the dermal fibroblasts and placebo groups (Fig. 8a).

Figure 8. Histological evaluation of the myocardial infarct for evidence of viable myocardium and genetically-labelled cell engraftment.

(A) Quantification of the amount of viable tissue within the infarct region (n=6 per group). (B) Immunohistochemistry of cardiac outgrowth cells genetically labelled with LacZ at the MI border. Beta-galactosidase positive cells in this region were elongated and “adult-like” as indicated by WGA plasma membrane staining and connexin expression at the borders and poles of the cells. (C) In contrast, cardiac outgrowth cells expressing beta-galactosidase within the central scar region were spherical and surrounded by fibrous tissue.

3.9 Cells injected into the infarct border zone differentiate into myocardial tissue

When infarct sections were examined for cells genetically labelled with nuclear targeted beta-galactosidase, cardiac outgrowth and CDCs were typically found as collections of cells at the border or the endocardial aspect of the infarct. These cells were elongated and expressed connexin at the borders of cells with enhanced detection at the intercalated disk of elongated cells (Fig. 8b). Typically within the infarct region itself, cardiac outgrowth and CDCs were found as discrete clusters of spherical cells surrounded by fibrous tissue (Fig. 8c). Rare clusters of spherical labelled cells could be found within myocardium remote from the infarct site, reflecting a migratory capacity for transplanted outgrowth and CDCs.

4.0 Discussion

This study demonstrates that cells grown directly from cardiac tissue possess a broad array of complementary sub-populations with the capacity to improve myocardial function after infarction. While previous work has provided a more limited characterization of cardiac outgrowth-derived cells following sub-selection or prolonged expansion,[6, 8, 10, 12, 13] this study focuses upon the common starting point of these protocols. As such, we provide direct evidence for functional improvements while avoiding confounders such as experimental selection biases or culture-acquired phenotypic drift.

We observed that a mesenchymal layer emerged from cultured cardiac tissue along with discrete groupings of CPCs. When comparing anatomical regions, we noted that outgrowth from sections of atrial tissue tended to grow faster and provided more cells at each harvest. These findings mirror the experience with neural stem cells where region-dependent cell growth kinetics have been reported.[28] Another possible explanation for our observation is that stem cell niches prominent in the atrial myocardium provide for enhanced growth from these myocardial sections.[29] Our results, however, do not support this explanation as other “niche rich” regions did not demonstrate similar capacity to generate enhanced quantities of cardiac outgrowth.

We found that cardiac outgrowth provides an aggregate of different CPCs and endothelial progenitor cell sub-populations. In a manner similar to neurospheres, we have shown that the sub-populations within cardiac outgrowth vary temporally with cells of embryonic-like origin (i.e., SSEA-1) predominating at the outset and cells with angiogenic markers proliferating towards the end of the culture period. The reason underlying this temporal growth dynamic is unknown but may involve serial depletion of slowly-replicating embryological-like precursors[6] with gradual increasing proliferation of hypoxia driven precursors.[30]

The origin of adult cardiac stem cells remains an area of considerable interest. One study has postulated that the c-Kit+ marker may represent proliferation of cardiac mast cells rather than genuine CPCs.[31] Indeed, mast cells have been extensively documented in the heart with estimates ranging between 1 and 5 cells/mm2.[32] Fortunately, the monoclonal antibody MAb AA4 recognizes two derivatives of the ganglioside GD1b that are unique to the surface of rat mast cells.[33] In our study, flow cytometry of cardiac outgrowth failed to demonstrate double-labelling of c-Kit+ CPCs with AA4 defined mast cells and refute the notion that c-Kit+ CPCs are mast cells. Our analysis of the spontaneous outgrowth from myocardial lineage labelled animals would further suggest these cells do not represent de-differentiated cardiomyocytes. Clearly, further work is required to better define the contribution of other cell populations to this product.

Using in vitro assays, we have shown that both CDCs and direct cardiac outgrowth are capable of differentiation into cardiac and endothelial cell phenotypes. As demonstrated with CDCs, a population of LacZ+ cells within the infarcted regions survives and differentiates into a cardiac phenotype.[10] In theory, these mechanisms may be synergistic with paracrine secretion mediating early survival/salvage of myocardium and/or recruitment of endogenous regeneration.[34-36] Recent work from our lab supports this notion, as long-term engraftment of CDCs is modest with only 5±3% of the injected cells persisting 3 weeks after surgery.[37, 38] While a portion of the transplanted cells do differentiate into endothelial and myocardial lineages, at least half of the improvements in vessel and cardiomyocyte densities are due to indirect effects of transplanted CDCs.[39] While it is interesting to note that both excess levels of the growth-stimulant IGF-1 and greater functional benefits occurred in the cardiac outgrowth group, the relative contribution of these cardioprotective/pro-angiogenic factors and direct differentiation to myocardial functional remains to be shown.

From a practical standpoint, this study provides clear evidence that direct implantation of the cellular outgrowth from cardiac samples improves post-injury myocardial function; further enrichment of “stemness” through the cardiosphere step may be unnecessary. This concept is attractive, as it would improve production efficiency and limit the risks of culture-acquired phenotypic drift or transformation.[14] Direct application of cardiac outgrowth to larger-scale models, or the clinical setting, is limited by a constant output return to the scale of production with the amount of outgrowth collected changing in proportion to the amount of tissue plated. Preclinical studies from our lab suggest that 2-3×107 CDCs infused via a coronary artery provide a safe balance between maximal engraftment and microembolization.[11] Projections from the growth kinetics of our study demonstrate that a typical human atrial appendage specimen (400 mg) would provide 8.0×106 cardiac outgrowth cells after 7 days in culture. This figure contrasts with our CDC experience with 1.7±0.4 million CDCs cultured after 45±7 days from a 21.0±1.9 g human biopsy, although subsequent methodological simplification has increased yields. [9, 10] Thus, if the initial amount of tissue is not severely restricted, direct outgrowth is a feasible strategy to provide early and effective cell therapy. In situations with tissue constraints, further study is warranted to characterize the effects of further expansion and culture-acquired phenotypic changes on functional outcomes.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the spontaneous outgrowth from cardiac samples contain distinct subpopulations of CPCs capable of differentiation, cytokine secretion and post MI functional benefits. These results accelerate and simplify the generation of autologous CPCs, providing new avenues for the direct translation of myocardial repair strategies.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Co-segregation of CPC markers Representative figures of the co-segregation of CPC markers (c-Kit, SSEA-1, abcg2) and the relevant isotype controls at first (A; week 1) and last (B; week 5) harvest from the explant culture.

5.0 Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIH (U54 HL081028 and R01 HL083109) and Dr Davis is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Clinician Scientist Award). In terms of competing interests, Dr Eduardo Marbán holds equity in a private company (Capricor Inc.) that licenses techniques used to manufacture cardiac stem cells. Dr Rachel Ruckdeschel Smith is presently employed by Capricor Inc. Capricor provided no support for this study. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6.0 References

- [1].Agah R, Kirshenbaum LA, Abdellatif M, Truong LD, Chakraborty S, Michael LH, et al. Adenoviral delivery of E2F-1 directs cell cycle reentry and p53-independent apoptosis in postmitotic adult myocardium in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2722–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chien KR, Olson EN. Converging pathways and principles in heart development and disease: CV@CSH. Cell. 2002;110:153–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anversa P, Kajstura J. Ventricular myocytes are not terminally differentiated in the adult mammalian heart. Circ Res. 1998;83:1–14. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beltrami AP, Urbanek K, Kajstura J, Yan SM, Finato N, Bussani R, et al. Evidence that human cardiac myocytes divide after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1750–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Brechtken J, Grindle S, Goh SK, Nelson W, et al. The adult human heart as a source for stem cells: repair strategies with embryonic-like progenitor cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(Suppl 1):S27–S39. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911–21. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Davis DR, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Cheng K, Terrovitis J, Malliaras K, et al. Validation of the cardiosphere method to culture cardiac progenitor cells from myocardial tissue. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, et al. Regenerative Potential of Cardiosphere-Derived Cells Expanded From Percutaneous Endomyocardial Biopsy Specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Johnston PV, Sasano T, Mills K, Evers R, Lee ST, Smith RR, et al. Engraftment, differentiation, and functional benefits of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells in porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;120:1075–83. 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, et al. Human cardiac stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tang YL, Shen L, Qian K, Phillips MI. A novel two-step procedure to expand cardiac Sca-1+ cells clonally. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:877–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rubio D, Garcia-Castro J, Martin MC, de la FR, Cigudosa JC, Lloyd AC, et al. Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3035–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Takashima A. Establishment of Fibroblast Cultures. Current Protocols in Cell Biology. 1998;2:2.1.1–2.1.12. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0201s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kizana E, Chang CY, Cingolani E, Ramirez-Correa GA, Sekar RB, Abraham MR, et al. Gene transfer of connexin43 mutants attenuates coupling in cardiomyocytes: novel basis for modulation of cardiac conduction by gene therapy. Circ Res. 2007;100:1597–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cingolani E, Correa GA Ramirez, Kizana E, Murata M, Cho HC, Marban E. Gene therapy to inhibit the calcium channel beta subunit: physiological consequences and pathophysiological effects in models of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2007;101:166–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cristofalo VJ, Charpentier R, Phillips PD. Serial propagation of human fibroblasts. In: Celis J, editor. Cell biology: A laboratory handbook. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. pp. 321–6. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–5. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, Nagy A, Lobe CG. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated excision. Genesis. 2000;28:147–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, et al. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med. 2007;13:970–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Barth AS, Kizana E, Smith RR, Terrovitis J, Dong P, Leppo MK, et al. Lentiviral Vectors Bearing the Cardiac Promoter of the Na(+)-Ca(2+) Exchanger Report Cardiogenic Differentiation in Stem Cells. Mol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stull LB, Leppo MK, Szweda L, Gao WD, Marban E. Chronic treatment with allopurinol boosts survival and cardiac contractility in murine postischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95:1005–11. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148635.73331.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grossman W, Brooks H, Meister S, Sherman H, Dexter L. New technique for determining instantaneous myocardial force-velocity relations in the intact heart. Circ Res. 1971;28:290–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lagostena L, Avitabile D, De FE, Orlandi A, Grassi F, Iachininoto MG, et al. Electrophysiological properties of mouse bone marrow c-kit+ cells co-cultured onto neonatal cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:482–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Horiguchi S, Takahashi J, Kishi Y, Morizane A, Okamoto Y, Koyanagi M, et al. Neural precursor cells derived from human embryonic brain retain regional specificity. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:817–24. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Urbanek K, Cesselli D, Rota M, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Hosoda T, et al. Stem cell niches in the adult mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600635103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Martin CM, Ferdous A, Gallardo T, Humphries C, Sadek H, Caprioli A, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1075–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pouly J, Bruneval P, Mandet C, Proksch S, Peyrard S, Amrein C, et al. Cardiac stem cells in the real world. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:673–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rakusan K, Sarkar K, Turek Z, Wicker P. Mast cells in the rat heart during normal growth and in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1990;66:511–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.2.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guo NH, Her GR, Reinhold VN, Brennan MJ, Siraganian RP, Ginsburg V. Monoclonal antibody AA4, which inhibits binding of IgE to high affinity receptors on rat basophilic leukemia cells, binds to novel alpha-galactosyl derivatives of ganglioside GD1b. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chimenti I, Smith RR, Leppo M, Gerstenblith G, Giacomello A, Messina E, et al. Secretion of pro-survival and pro-angiogenic growth factors in vitro and in vivo by cardiac progenitor cells from human biopsies. Circulation Research. 2007;101(11) [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, Messina E, Giacomello A, Marban E. Abstract 3182: Paracrine Contribution versus Direct Regeneration in Cardiosphere-Derived Cell Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2009;120:S756–S75a. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Smith RR, Chimenti I, Marban E. Unselected human cardiosphere-derived cells are functionally superior to c-kit- or CD90-purified cardiosphere-derived cells. Circulation. 2008;118 [Google Scholar]

- [37].Terrovitis J, Lautamaki R, Bonios M, Fox J, Engles JM, Yu J, et al. Noninvasive quantification and optimization of acute cell retention by in vivo positron emission tomography after intramyocardial cardiac-derived stem cell delivery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1619–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li Z, Lee A, Huang M, Chun H, Chung J, Chu P, et al. Imaging survival and function of transplanted cardiac resident stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, Gerstenblith G, Messina E, Giacomello A, et al. Relative Roles of Direct Regeneration Versus Paracrine Effects of Human Cardiosphere-Derived Cells Transplanted Into Infarcted Mice. Circ Res. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. CIRCRESAHA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Co-segregation of CPC markers Representative figures of the co-segregation of CPC markers (c-Kit, SSEA-1, abcg2) and the relevant isotype controls at first (A; week 1) and last (B; week 5) harvest from the explant culture.