Abstract

Objective

This study investigated the effects of ginsenoside Rb1 (Rb1) on injury-induced intimal hyperplasia in ApoE knock out (ApoE −/−) mice. We also examined the value of an ultrasound micro-image system in dynamic monitoring of lumen diameter and flow velocity.

Methods

After guide wire injury of the distal left common carotid artery (CCA), ApoE−/− mice were treated with intraperitoneal infusion of normal saline (NS), Homocysteine (Hcy), ginsenoside Rb1 (Rb1), or Hcy+Rb1 for 4 weeks. Bilateral CCA luminal diameters and flow velocities were measured with an ultrasound micro-image system before surgery and weekly afterwards. Following the final ultrasound, CCAs were harvested and analyzed for intima-medium thickness ratios.

Results

Progressive reduction in luminal diameters and increase in flow velocity of the injured left distal CCA segment were observed using ultrasound micro-imaging system in all groups comparing to the relatively stable left proximal CCA and right CCA. The NS and Hcy groups had significant higher degree of diameter reduction comparing to the Rb1 and Rb1+Hcy groups. The ultrasound findings were consistent with histology analyses at 4 weeks post-op.

Conclusions

The study suggested that Rb1 attenuated the effects of Hcy on injured carotid arteries of ApoE −/− mice. The study also showed that ultrasound micro-image system was a reliable tool in monitoring luminal reduction after injury in murine model. This study establishes a fundamental step of in vivo monitoring the therapeutic effects of agents in a murine model without sacrificing the animals.

Keywords: Atherosclesorosis, Ultrasound, Intimal hyperplasia, Homocysteine, Guidewire injury, Ginsenoside Rb1, Apo E knock out mice, restenosis

Introduction

Restenosis secondary to neointima formation decreases the long-term clinical success of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions.(1, 2) However, molecular mechanisms of intimal hyperplasia (IH) are poorly understood and treatment options are limited. Various animal models have been used to investigate the mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies for intimal hyperplasia. Our previous study has validated a clinical relevant carotid artery injury model with reproducible stenosis in C57/BL mice.(3) Aged apolipoprotein E deficient (ApoE−/−) mice have the tendency of developing atherosclerotic lesions resemble humans. Our early evaluation of ApoE−/− mice showed more aggressive and early IH with marked stenosis shown at four weeks following guide wire injuries.

Rb1, a major constituent of ginseng, has shown a protective role in various vascular injuries due in part to preventing free radical injury and inducing nitric oxide (NO) release.(4–7) We demonstrated that Rb1 blocked homocysteine (Hcy)-induced endothelial vasomotor dysfunction and free-radical production in porcine coronary arterial rings and endothelium cells.(8, 9) In this study, we investigated the in vivo effects of Rb1 and Hcy on intimal hyperplasia in ApoE −/− mice. In addition to traditional histomorphology assessment of stenosis, we also utilized a dynamic ultrasound micro-imaging system, Vevo 770 (VisualSonics), in monitoring the progression of intimal hyperplasia. The Vevo 770 high-frequency ultrasound micro-imaging system equipped with a 40MHz probe offers a spatial resolution as small as 30 microns. The system potentially allows longitudinal study of progression of lesions without sacrificing animals. Both luminal diameters of injured carotid arteries and flow velocities were measured. The sonographic findings at 4 weeks post-op were compared to the histomorphological findings at the end of the study.

Methods

Twelve-week old ApoE−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and fed standard laboratory food with water ad libitum. Mice were acclimated for at least two weeks prior to interventional procedures. All procedures were performed under a standard protocol that has been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stanford University. All protocols follow federal and institutional guidelines for animal welfare. Hcy (DL-homocysteine) and Rb1 (99.7% purity from Panax quinquefolium root) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Stability of Rb1 in vivo

A pilot study was performed to determine the stability of Rb1 in vivo and the consistency of plasma concentration following intraperitoneal infusion. A 28-day mini-osmotic pump (ALZET, Model 2004, Cupertino, CA) filled with 0.35mM of Rb1 was implanted in the peritoneum cavity for continuous intraperitoneal (IP) administration. The concentrations of Rb1 was based on our previous studies(3, 8, 9). The animals were sacrificed at 2, 3, and 4 weeks, and Rb1 concentrations in the pump and plasma were evaluated with lipid chromatography-mass spectrometry and mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to validate consistency and stability of Rb1.

2.1. Guide wire injury

Mice were anesthetized for all surgeries and ultrasound examinations with inhalation of isoflurane. Guide wire injury techniques have been described in our previous study.(3) Briefly, Bilateral carotid arteries were exposed through a midline incision. After the left proximal common carotid artery (CCA) and the internal carotid artery (ICA) with microclamps (S&T model B1 and B2, Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, respectively) were controlled, a rigid 0.010″ guide wire was introduced to the mid CCA through an external carotid artery (ECA) arteriotomy. A total of ten passes were made to ensure adequate denudation on the mid and distal CCA. Subsequently, the ECA was ligated and microclamps were released to reestablish in-line flow from CCA to ICA. During the procedure, the right carotid artery was isolated but not injured, and was used as the un-injured control. After hemostasis was achieved, the skin was closed with a 4-0 nylon suture. Subsequently, the animals were randomly divided into four treatment groups (n=7 per group): vehicle control (normal saline), homocysteine (Hcy, 14.5 mM), Rb1 (0.35 mM), or combined Hcy (14.5 mM) and Rb1 (0.35 mM) (Hcy+Rb1). A 28-day mini-osmotic pump (ALZET, Model 2004, Cupertino, CA) filled with 250 μl of different solution was implanted in the peritoneum cavity for continuous IP administration. The doses and concentrations of Hcy or Rb1 were determined based on our previous studies(3, 8, 9).

2.2. Ultrasound evaluations

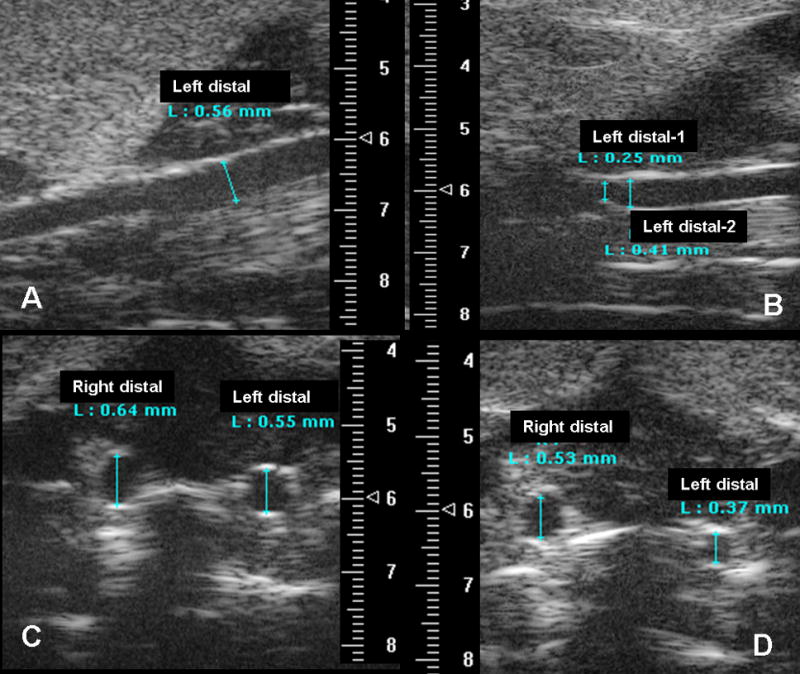

All mice underwent carotid evaluations using a VisualSonics Vevo 770 high-resolution ultrasound micro-image system with a 40 MHz probe focusing at 4.5mm depth before surgeries (baseline) and weekly afterwards. The examiners were blinded on the treatment groups to avoid potential operator bias. Diameters of bilateral CCA were measured at distal and proximal CCAs in both longitudinal and transverse views (Figure 1). We only used measurements obtained through transverse views to ensure that the maximal diameter was recorded. Flow velocities of distal and proximal CCAs were measured at a consistent angle each time. The left proximal CCA was a negative control as only the mid and the distal left CCAs were denuded by a guide wire while endothelium of the proximal CCA remained intact. Following the last ultrasound study at four weeks post-injury, the mice were sacrificed and bilateral CCAs were harvest for histology analyses. The degrees of stenoses and flow velocity were normalized with baseline CCA diameter and expressed as percentage of baseline.

Figure 1.

Representative longitudinal and transverse diameter measurement of distal CCA prior to (A, C) and 4 weeks after injury (B, D) in normal saline treated ApoE −/− mouse. Numbers on the scales marked 1mm and the diameters were measured electronically using the software provided by the system. The average depth of carotid arteries from the skin was 6mm. L: diameter length; Left distal-1 in panel B correlated to the location of significant intimal hyerplasia

2.3. Histomorphometry analysis

Bilateral CCAs were harvested using a standard protocol that has been established in our research laboratory.(3) Animals were euthanized with CO2 and perfused with normal saline, followed by 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.0) for 10 minutes at a constant pressure of 100 mmHg. The CCAs on both sides were isolated and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for an additional 48 hours before going through paraffin embedding. Serial tissue sections (5 μm) were obtained, starting at the bifurcation. Three sections (50 μm apart) at the site of maximal luminal reduction were analyzed. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H-E). Areas within lumen, internal and external elastic laminae were measured by planimetry of digitized images obtained by a bright-field microscope (Infinity 1, Meiji) with the use of ImageJ software (NIH). To calculate IMT for each vessel cross-section, the linear distance between internal elastic lamina and external elastic lamina was measured independently in four places, each at 90° apart and averaged. The average of the 4 measurements at 4 quadrants was recorded and the ratio of intima-to-media thickness was normalized using the contralateral uninjured right CCA (normalized IMT).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Data from the different groups were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test (two-tails, Minitab). In addition, analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to analyze data of flow velocity and luminal diameter. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistics are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

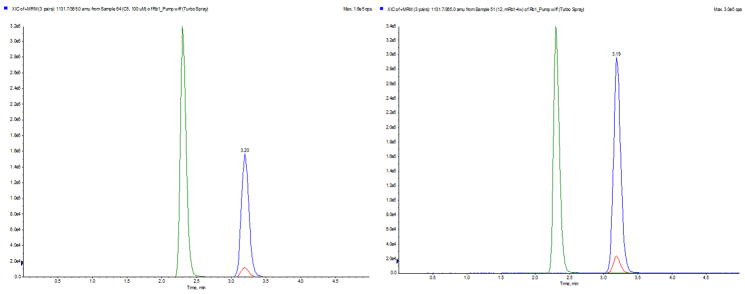

The stability of Rb1 within abdominal cavities of mice was confirmed using LC-MS/MS. We demonstrated the same molecular composition of Rb1 within the osmotic pumps four weeks after implantations comparing to that at the time of implantations (Figure 2). The plasma concentrations of Rb1 in the Rb1-treated group were also consistent between the week 2 to week 4 at a mean of 1.72±0.21 μM comparing to <0.1 μM in the control animals.

Figure 2.

LC-MS/MS analysis of osmopump content before implantation into mice (Left) and after four weeks being implanted in a mice peritoneal cavity (Right). Internal standard, stevioside with a retention time of 2.35 min was the green peak. MRM chromatogram confirmed stable Rb1.

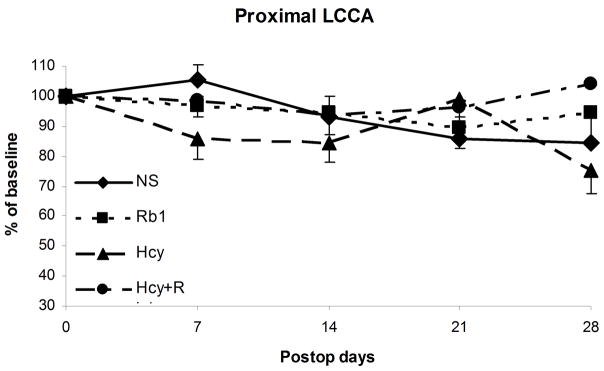

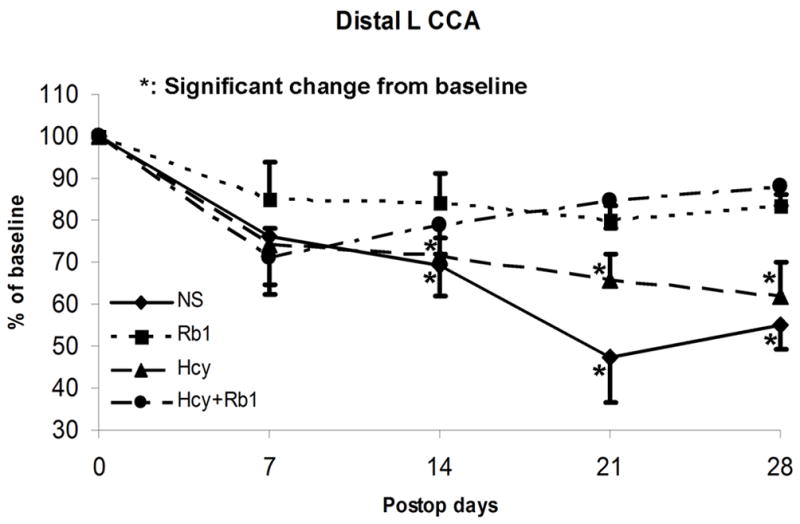

Luminal diameters of both proximal and distal CCAs were measured and compared. The preoperative diameters of left CCAs at baseline were relative consistent among all groups with a mean of 0.56mm (ranging 0.49mm to 0.63mm) (Figure 1). Proximal and distal left CCA diameters were normalized with right proximal and distal CCA respectively. There were no significant change in the normalized luminal diameters at proximal left CCA (uninjured portion) over time among all groups (Figure 3a). However, the distal left CCAs (injured portion) had significant decreases in luminal diameters among all groups at four weeks (P<0.05) (Figure 3b). The NS and Hcy groups had significant higher degree of diameter reductions (55% and 62% of baseline) comparing to the Rb1 and Rb1+Hcy groups (83.5% and 88.1% of baseline, respectively, P<0.03) (Figure 3b). Additionally, NS and Hcy groups showed early and persistent stenosis. Mean luminal diameters of distal CCA in the NS group were 76%, 69.4%, 47.2%, and 55% of the baseline at 7, 14, 21, 28 days post-procedure. Similarly, distal CCA of the Hcy group were also significantly narrowed measuring an average of 74.4%, 71.5%, 65.5%, and 62% of the baseline at each time interval respectively. There is no statistical difference between Hcy and NS groups. The Rb1 group showed significant improvement in luminal diameter (85.1%, 84.3%, 79.9%, and 83.5% of the baseline, respectively) comparing to the NS group (P=0.019) based on ANOVA analyses. Addition of Rb1 to Hcy treatment (Hcy+Rb1 group) significantly decreased the degree of stenosis, which was evident by less mean luminal narrowing (71%, 79%, 84.4%, and 88.1% of baseline, respectively) comparing to the Hcy group (P=0.038).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a: Luminal diameters of proximal left CCA showed no significant change among all groups

Figure 3b: Significant diameter reduction in all groups at four weeks. The Rb1 and Hcy+Rb1 groups had significantly less reduction comparing to the NS and Hcy groups.

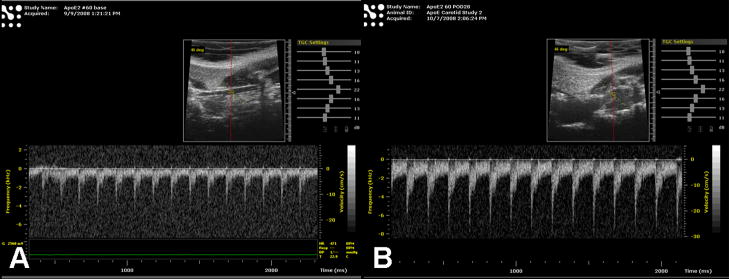

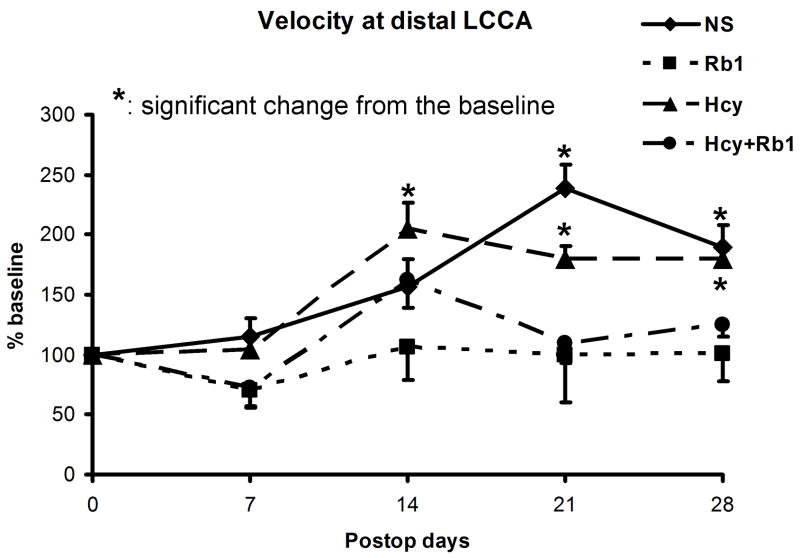

Flow velocities at injured distal left CCAs were measured and normalized with preoperative baseline velocity (Figure 4a). The NS groups showed significant increase in flow velocity at 21 and 28 days (239.2% and 189.2% of baseline respectively, P<0.05) and the Hcy group showed more aggressive early increase in velocity comparing to the baseline (p<0.01) (Figure 4b). No significant velocity change was observed in either the Rb1 group or the Hcy+Rb1 groups at each time points comparing to baseline. The Rb1+Hcy group had significant less velocity increase at 14 and 28 days comparing to the Hcy group (P<0.01). Additionally, the Rb1 group was significantly protected from velocity increase comparing to the NS and Hcy group (P=0.03 and 0.02, respectively).

Figure 4.

Figure 4a: Representative velocity measurement of left distal CCA prior to (A) and 4 weeks after injury (B) in normal saline treated ApoE −/− mouse.

Figure 4b: Significant flow velocity increases shown in the NS and Hcy groups, but not in the Rb1 and Rb1+Hcy groups

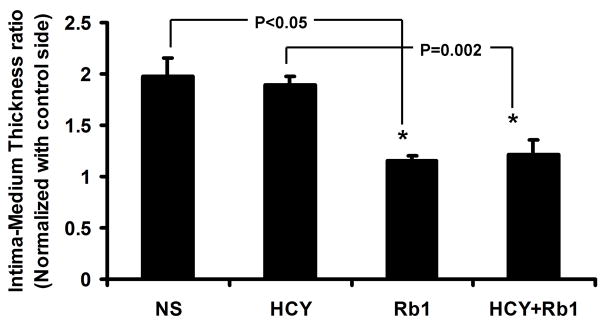

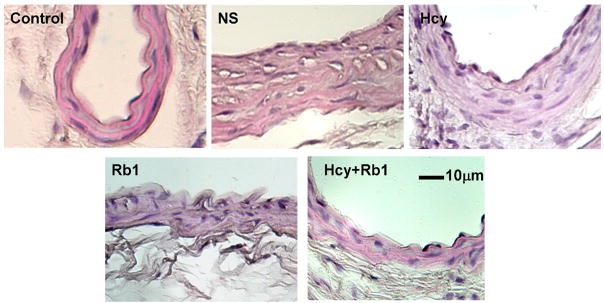

After four weeks of survival period, the animals were sacrificed and bilateral CCAs were harvest for histology analysis immediately following ultrasound evaluations. IMT of the injured left CCA was normalized with the uninjured right CCA. The NS group has similar normalized IMT comparing to the Hcy Group (1.98 and 1.89, respectively). The Rb1 group had significant reduction in normalized IMT comparing to the NS Group (1.15 vs. 1.98, P<0.05) (Figure 5a and 5b). Importantly, the Rb1+Hcy group had significantly decreased normalized IMT comparing to the Hcy group (1.21 vs. 1.89, P=0.002).

Figure 5.

Figure 5a: Significant decreases in normalized IMT in the Rb1 and Hcy+Rb1 groups comparing to the NS and Hcy Groups

Figure 5b: Representative H&E stain of cross-sections of injured CCA at the area of maximal diameter reduction. Bar = 10 μM

4. Discussion

The Vevo 770 ultrasound system is a new generation of high-resolution micro-imaging system that has recently been validated for assessing mouse carotid artery in vivo.(10) Using our previously validated murine model, we demonstrated that ginsenoside Rb1 attenuated Hcy-exacerbated intimal hyperplasia after guide wire injury in ApoE−/− mice. This study, for the first time, also demonstrated that Vevo770 micro-imaging system with a 40MHz transducer can be used to monitor therapeutic effect of Rb1 in ApoE−/− mice. Longitudinal sonographic evaluation allows us to identify progression of intimal hyperplasia and potentially investigate the mechanisms of each stage of lesion formation without sacrificing animals.

Intimal hyperplasia impairs the long-term clinical success of peripheral arterial interventions and accounts for majority of delayed procedure failures. Genetically modified mice are commonly used for studying intimal hyperplasia in vivo. Multiple murine models have been proposed to investigate this challenging dilemma in cardiovascular interventions(11) (12–14). Among them, guide wire injury model closely mimics clinical scenarios by maintaining in-line flow following mechanical injury, but it is particularly technical challenging. We modified the carotid guide wire injury techniques and validated consistent result of inducing intimal hyperplasia in C57/BL mice, a parent strain of ApoE−/− mice.(3) ApoE−/− mice develop arterial lesions that increase with age and progress to atherosclerotic plaques that resemble human diseases. Our initial evaluation demonstrated that Apo E−/− mice, unlike their parent strain C57/BL mice, developed more aggressive and early intimal hyperplasia at four weeks following guide wire injury (data not shown). Four-week survival interval was therefore chosen as the end point. Consistent with our initial observation, the control (NS) group developed similar aggressive intimal hyperplasia as the Hcy group, which was reflected by elevations in Doppler velocities and reductions in luminal diameters at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, and was confirmed by histological analyses at 28 days. It is possible that dysfunction of lipid metabolism in ApoE−/− mice led to exacerbated intimal hyperplasia even in the control (NS) group. Importantly, both Rb1 and Rb1+Hcy group showed no significant change comparing to the baseline. This study validated our previous in vitro findings and confirmed that Rb1 could attenuate intimal hyperplasia in vivo. Interestingly, figure 3b showed that Hcy, Hcy+Rb1, and NS groups had similar diameter reductions (74%, 71%, and 76%, respectively), while Rb1 had slightly less diameter reduction (85%) at Day 7 comparing to post-op Day 0 (100%). The differences among groups Hcy, Hcy+Rb1, and NS were minimal (<5%) and none of the values at Day 7 reached statistically significant. However, figure 4b showed that NS and Hcy groups had higher flow velocities (114% and 104% of Day 0) than Hcy+Rb1 and Rb1 groups (both at 72% of Day 0) at Day 7, which suggested slightly smaller diameters in the NS and Hcy groups. The values did not reach statistical significance either. We believe that these observed minor discrepancies at Day 7 were likely due to measurement variations and sample size. The early changes of vessel diameter and flow velocity at Day 7 were not significant to account for the effects of Rb1, Hcy, or the combination of Hcy+Rb1.

Ultrasound micro-imaging system has been used widely in characterizing aortic aneurysms in murine models.(15–20) However, their utilization in evaluating murine carotid arteries is limited due in part to inadequate special resolution. Recently, Ni and colleagues reported reliable assessment of carotid plaque morphology in ApoE−/− using a new generation ultrasound micro-imaging system, Vevo 770 equipped with a 55 MHz prob.(10) The authors demonstrated that cross-sectional histopathlogy data was consistent with micro-ultrasonography at eight weeks after initial injury. Unlike their study of evaluating morphological details of the plaques, we used the same micro-imaging system to assess the progression of intimal hyperplasia over a period of four weeks. At this early stage of investigation, measuring IMTs of murine carotid arteries following guide wire injuries could not be achieved accurately. Therefore, we decided to use more reproducible and reliable measurements of vessel diameters and flow velocities. The measurements were obtained by an independent operator who had extensive experiences in the ultrasound micro-imaging system and was blinded on the treatment groups. We demonstrated progressively elevated flow velocities and decreased luminal diameters in the injured vessels among all groups over a four-week treatment period, particularly in the Hcy and NS groups. We also showed no significant change over time in the uninjured vessels among all groups. The extents of restenoses measured by the vessel diameter and flow velocity were consistent with histological analyses of IMT at 28 days. This study suggested that ultrasound micro-image system could be used reliably by an experienced operator in monitoring the progression of intimal hyperplasia in murine carotid arteries. Flow velocity and vessel diameter are complimentary and should be used conjunctively to achieve a reliable result. By imaging the entire artery, the ultrasound micro-imaging system can also locate the area of lesions and help to reduce the amount of labor-intensive histomorphology analyses. Importantly, this study establishes a fundamental step for in vivo monitoring the therapeutic effects of agents on intimal hyperplasia in a murine model without sacrificing the animals.

Similar to clinical ultrasound imaging systems, the accuracy and consistency of the imaging results generated by this system is operator- and learning curve-dependent. Inappropriately utilization of this system can introduce bias and inconsistent results. With the help of an independent operator who has extensive experiences in Vevo 770 ultrasound micro-imaging (GS), we were able to obtain reliable results and observe incremental changes of restenosis in mice carotid arteries following guide wire injuries. To adapt this in vivo imaging modality, additional trainings may be necessary.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21 AT005136-01A1 (W. Zhou).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matter CM, Ma L, von Lukowicz T, Meier P, Lohmann C, Zhang D, Kilic U, Hofmann E, Ha SW, Hersberger M, Hermann DM, Luscher TF. Increased Balloon-Induced Inflammation, Proliferation, and Neointima Formation in Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) Knockout Mice. Stroke. 2006;37:2625–2632. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000241068.50156.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Chiu Wong S, Hong MK, Kovach JA, Leon MB. Arterial Remodeling After Coronary Angioplasty: A Serial Intravascular Ultrasound Study. Circulation. 1996;94:35–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai H, Dong Y, Wang X, Zhou W. Ginsenoside Rb1 Attenuates Homocysteine-Augmented Guidewire Injury-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia in Mice. J Surg Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou W, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen CJ. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of ginseng root for cardiovascular disease. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:RA187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillis CN. Panax ginseng pharmacology: a nitric oxide link? Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X. Cardiovascular protection by ginsenosides and their nitric oxide releasing action. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:728–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott GI, Colligan PB, Ren BH, Ren J. Ginsenosides Rb1 and Re decrease cardiac contraction in adult rat ventricular myocytes: role of nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1159–1165. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohashi R, Yan S, Mu H, Chai H, Yao Q, Lin PH, Chen C. Effects of homocysteine and ginsenoside Rb1 on endothelial proliferation and superoxide anion production. J Surg Res. 2006;133:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou W, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Ginsenoside Rb1 blocks homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni M, Zhang M, Ding SF, Chen WQ, Zhang Y. Micro-ultrasound imaging assessment of carotid plaque characteristics in apolipoprotein-E knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindner V, Fingerle J, Reidy MA. Mouse model of arterial injury. Circ Res. 1993;73:792–796. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Abrahams JM, Smith LM, McVey JH, Lechler RI, Dorling A. Regenerative repair after endoluminal injury in mice with specific antagonism of protease activated receptors on CD34+ vascular progenitors. Blood. 2008;111:4155–4164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shagdarsuren E, Bidzhekov K, Djalali-Talab Y, Liehn EA, Hristov M, Matthijsen RA, Buurman WA, Zernecke A, Weber C. C1-esterase inhibitor protects against neointima formation after arterial injury in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Circulation. 2008;117:70–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.715649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooley BC. Mouse strain differential neointimal response in vein grafts and wire-injured arteries. Circ J. 2007;71:1649–1652. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barisione C, Charnigo R, Howatt DA, Moorleghen JJ, Rateri DL, Daugherty A. Rapid dilation of the abdominal aorta during infusion of angiotensin II detected by noninvasive high-frequency ultrasonography. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujikura K, Luo J, Gamarnik V, Pernot M, Fukumoto R, Tilson MD, 3rd, Konofagou EE. A novel noninvasive technique for pulse-wave imaging and characterization of clinically-significant vascular mechanical properties in vivo. Ultrason Imaging. 2007;29:137–154. doi: 10.1177/016173460702900301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goergen CJ, Johnson BL, Greve JM, Taylor CA, Zarins CK. Increased anterior abdominal aortic wall motion: possible role in aneurysm pathogenesis and design of endovascular devices. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:574–584. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg A, Pakkiri P, Dai E, Lucas A, Fenster A. Measurements of aneurysm morphology determined by 3-d micro-ultrasound imaging as potential quantitative biomarkers in a mouse aneurysm model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knipp BS, Ailawadi G, Sullivan VV, Roelofs KJ, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr Ultrasound measurement of aortic diameters in rodent models of aneurysm disease. J Surg Res. 2003;112:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin-McNulty B, Vincelette J, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Wang YX. Noninvasive measurement of abdominal aortic aneurysms in intact mice by a high-frequency ultrasound imaging system. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]