Abstract

The multivesicular body (MVB) sorting pathway is required for a number of biological processes, including downregulation of cell-surface proteins and protein sorting into the vacuolar lumen. The function of this pathway requires endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) composed of class E vacuolar protein sorting (Vps) proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, many of which are conserved in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Of these, sst4/vps27 (homologous to VPS27) and sst6 (similar to VPS23) have been identified as suppressors of sterility in ste12Δ (sst), although their functions have not been uncovered to date. In this report, these two sst genes are shown to be required for vacuolar sorting of carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) and an MVB marker, the ubiquitin–GFP–carboxypeptidase S (Ub–GFP–CPS) fusion protein, despite the lack of the ubiquitin E2 variant domain in Sst6p. Disruption mutants of a variety of other class E vps homologues also had defects in sorting of CPY and Ub–GFP–CPS. Sch. pombe has a mammalian AMSH homologue, sst2. Phenotypic analyses suggested that Sst2p is a class E Vps protein. Taken together, these results suggest that sorting into multivesicular bodies is dependent on class E Vps proteins, including Sst2p, in Sch. pombe.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic selections in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have resulted in the isolation of a large number of vps mutants defective in the delivery of proteins to lysosome-like vacuoles. These define more than 60 complementation groups and have been categorized into six classes (A–F) with respect to their morphology, vacuolar protein sorting and acidification defects (Raymond et al., 1992; Banta et al., 1988). Class E vps mutants fail to transport newly synthesized hydrolases efficiently to the vacuole (Raymond et al., 1992; Piper et al., 1995; Rieder et al., 1996). Instead, hydrolases accumulate with endocytosed receptors in an exaggerated perivacuolar class E compartment. In Sac. cerevisiae class E vps mutants, FM4-64 accumulated asymmetrically at the vacuolar membrane either in the form of a crescent-shape on one side of the vacuole or in the form of a small ring-like structure adjacent to the vacuole (Raymond et al., 1992). Electron microscopic analysis revealed the presence of class E compartments consisting of stacks of curved membrane cisternae in class E vps mutants (Rieder et al., 1996; Babst et al., 1997).

The class E vps genes are largely conserved in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and mammalian genomes (Babst, 2005; Winter & Hauser, 2006; Takegawa et al., 2003), and the majority of the proteins encoded are constituents of three separate heteromeric protein complexes called ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II and ESCRT-III (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) (Babst, 2005; Bowers & Stevens, 2005; Winter & Hauser, 2006). These complexes are proposed to be the sorting machinery for endosomal structures called multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs are part of the endosomal system for degradation of transmembrane proteins, and are formed by invagination and budding of vesicles from the limiting membrane of endosomes into the lumen of the compartment. Two types of MVB cargo proteins are found in budding yeast. One group consists of the endocytosed surface proteins that function as transporters (e.g. Gap1p, Fur4p and Ste6p) and receptors (e.g. Ste2p and Ste3p) (Rieder et al., 1996; Soetens et al., 2001; Dupré & Haguenauer-Tsapis, 2001; Krsmanović et al., 2005; Shih et al., 2002). The other is biosynthetic cargo, i.e., vacuolar proteins transported directly from the late Golgi to the anterograde and biosynthetic pathway, such as carboxypeptidase S (CPS), Phm5p, and Sna3p (Odorizzi et al., 1998; Reggiori & Pelham, 2001). In mammalian cells, MVBs are also involved in budding of viruses and in lipid partitioning (Piper & Luzio, 2001).

ESCRT complexes function sequentially in the sorting of transmembrane proteins into the MVB pathway and in the formation of MVB vesicles (reviewed in Babst, 2005; Bowers & Stevens, 2005; Winter & Hauser, 2006). ESCRT-I localization to the MVB membrane depends on its interaction with the Vps27/Hse1 complex, also called ESCRT-0 (Bowers & Stevens, 2005). The Vps27/Hse1 complex is the sorting receptor for ubiquitinated cargo proteins at the MVB. The ESCRT-I complex binds to ubiquitinated cargo and activates ESCRT-II, although this activation mechanism is not yet understood. ESCRT-II in turn initiates the oligomerization of small coiled-coil proteins, resulting in the formation of the ESCRT-III complex, which concentrates MVB cargo (Babst et al., 2002). ESCRT-III recruits the deubiquitinating enzyme Doa4p, which removes ubiquitin (Ub) from the cargo protein prior to sorting into the MVB vesicles (Amerik et al., 2000). After protein sorting is completed, the AAA-type ATPase, Vps4p, binds to ESCRT-III and disassembles ESCRT-III in an ATP-dependent manner (Babst et al., 1997, 1998).

The mammalian Hrs/STAM complex, equivalent to the Vps27/Hse1 complex in budding yeast, binds two deubiquitinating enzymes, the JAMM/MPN+ family member AMSH (associated molecule with the SH3 domain of STAM) and the ubiquitin-specific protease family member UBPY (ubiquitin isopeptidase Y) (McCullough et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 1999; Row et al., 2006). These two deubiquitinating enzymes may share redundant functions: the promotion of MVB cargo recycling by opposing ubiquitin ligase activity, and the deubiquitination of MVB cargo prior to lysosomal degradation. Earlier work demonstrated that AMSH counteracts the E3-ligase through deubiquitination of MVB cargo (McCullough et al., 2004). Recent studies showed that AMSH binds to the ESCRT-III complex in a STAM-independent manner (Agromayor & Martin-Serrano, 2006; Tsang et al., 2006), in support of the suggestion that AMSH might be a counterpart of Doa4p (Agromayor & Martin-Serrano, 2006). The function of UBPY is uncertain. One report concludes that UBPY negatively regulates degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Mizuno et al., 2005), which is downregulated via MVB sorting and lysosomal degradation. Others conclude that UBPY-mediated deubiquitination is essential for EGFR degradation (Row et al., 2006; Alwan & van Leeuwen, 2007). UBPY also catalyses deubiquitination of Eps15, suggesting that it controls the level of ubiquitinated protein required for maintaining the morphology of the endosome (Mizuno et al., 2006).

Recent completion of the Sch. pombe genome sequence revealed that class E Vps proteins were largely conserved in this species (Takegawa et al., 2003). Nonetheless, the MVB pathway in Sch. pombe is still poorly understood. Our previous study identified six genes as suppressors of ste12 (sst genes), including casein kinase II and a calcium transporter (Onishi et al., 2003). Ste12p is a phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PtdIns-3-P) 5-kinase, equivalent to Sac. cerevisiae Fab1p (McEwen et al., 1999). Two class E vps genes are included among the sst genes. sst4/vps27+ is a VPS27 homologue and sst6+ is similar to VPS23 of Sac. cerevisiae. In addition, sst2+ is a homologue of mammalian AMSH.

Here, we describe analyses of common phenotypes in class E mutants in fission yeast. Loss of these proteins resulted in mild defects in maturation of carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) and sorting into MVBs. This is the first report showing that the MVB pathway functions in Sch. pombe and that the roles of class E Vps proteins in MVB sorting are conserved.

METHODS

Strains, media and genetic methods.

Sch. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Standard rich medium (YES) and synthetic minimal medium (MM) for growing Sch. pombe were used as described previously (Moreno et al., 1991). Sch. pombe cells were transformed by the lithium acetate method or by electroporation as described previously (Okazaki et al., 1990; Suga et al., 2000; Suga & Hatakeyama, 2001; Morita & Takegawa, 2004). Standard genetic methods have been described previously (Alfa et al., 1993).

Table 1.

List of Sc. pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| WA8 (THP17) | h90leu1 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | Koga et al. (2004) |

| KJ100-7B | h90leu1 ura4-D18 | Dr K. Tanaka (Tokyo University) |

| ARC039 | h−leu1-32 ura4-C190T | Asahi Glass Co. Ltd |

| vps34Δ | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 vps34 : : ura4+ | Takegawa et al. (1995) |

| MTD2 | h+ leu1-32 his2 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 cpy1 : : ura4+ | Tabuchi et al. (1997) |

| sst4Δ | WA8 vps27 : : ura4+ | This study |

| hse1Δ | WA8 hse1 : : LEU2 | This study |

| sst6Δ | WA8 sst6 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps28Δ | WA8 vps28 : : ura4+ | This study |

| dot2Δ | KJ100-7B dot2 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps25Δ | KJ100-7B vps25 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps36Δ | KJ100-7B vps36 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps2Δ | ARC039 vps2 : : LEU2 | This study |

| vps20Δ | WA8 vps20 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps24Δ | WA8 vps24 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps32Δ | WA8 vps32 : : ura4+ | This study |

| vps4Δ | KJ100-7B vps4 : : ura4+ | This study |

| sst2Δ | KJ100-7B sst2Δ : : loxP | This study |

| ubp1Δ | ARC039 ubp1 : : ura4+ | This study |

| ubp4Δ | ARC039 ubp4 : : ura4+ | This study |

| ubp12Δ | ARC039 ubp12 : : ura4+ | This study |

Pulse–chase and immunoblot analyses of the Sch. pombe Cpy1 protein.

Pulse–chase analysis and immunoprecipitation of the vacuolar CPY from Sch. pombe (Cpy1p) were carried out as previously described (Tabuchi et al., 1997). Antibody incubations were performed using rabbit polyclonal antibody against Sch. pombe Cpy1p as described (Tabuchi et al., 1997).

Colony blot assays to detect mislocalized Cpy1p were performed as previously described (Cheng et al., 2002). Briefly, cells were spotted on nitrocellulose membranes and grown for 2 days at 30 °C. After removing cells by washing, the nitrocellulose membranes were subjected to immunodetection of Cpy1p using rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against Sch. pombe Cpy1p (1 : 500 dilution), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antiserum (Amersham Biosciences) and the Amersham ECL system.

Gene disruptions.

The sst4/vps27+ locus (SPAC19A8.05C) was disrupted in the wild-type Sch. pombe strain by replacing an internal sst4/vps27+ gene fragment with the Sch. pombe ura4+ gene. To amplify the DNA fragment carrying the sst4/vps27+ gene from the complementing DNA, the following oligonucleotides were used: sense, 5′-ATACCGAGATGTGCTAAGCTGCCCGC-3′ and antisense, 5′-CAGACATGCATTGTCGATAA-3′. A 2.1 kbp fragment was recovered and ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). An XbaI site within the cloned sst4/vps27+ open reading frame was digested and a 1.6 kbp ura4+ gene was inserted.

To disrupt the sst6+ locus (SPAC11H11.01), the following oligonucleotides were used: sense, 5′-GAAAATGAAGCTCCTCCTGTTATCCCTGC-3′ and antisense, 5′-TCAAACAGCACTTCATACTTAATGTTCTGC-3′. A 1.4 kbp fragment was recovered and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Two HincII sites within the cloned sst6+ open reading frame were digested and the ura4+ gene was inserted. A linearized DNA fragment carrying the disrupted sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ genes was used to transform wild-type haploid WA8 strains, and ura+ transformants were selected. To confirm that one of the sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ genes had been disrupted, ura+ transformants were analysed by Southern blot and PCR to verify correct integration of the deletion constructs.

The sst2+ deletion was generated as follows: 0.6 kbp fragments carrying the promoter and terminator were amplified by PCR and then cloned sequentially into XhoI and HindIII sites (promoter) and EcoRI and BamHI sites (terminator) of pBS loxP-ura4-loxP (Iwaki & Takegawa, 2004), followed by amplification of the disruption cassette and transformation of yeast. ura+ transformants were analysed by PCR and ura4+ was removed by Cre-mediated recombination using pREP41-Cre (Iwaki & Takegawa, 2004).

Plasmid constructions.

pREP41-Ub-GFP-SpCPS was constructed as follows. The 225 bp fragment encoding a single ubiquitin molecule from the ubi4 gene was amplified and cloned into the NdeI and SalI sites of pREP41, and confirmed by sequence analysis. A CPS1 homologue, SPAC24C9.08 (SpCPS), was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pTN54, a derivative of the thiamine-repressible expression vector pREP41 (Nakamura et al., 2001), resulting in plasmid pTN54/SpCPS, which expresses an N-terminal GFP-tagged SpCPS. The GFP–SpCPS fusion was amplified by PCR and cloned into the SalI and BamHI sites of pREP41 containing the ubiquitin sequence, resulting in plasmid pREP41-Ub-GFP-SpCPS. To generate a ura4+ marker plasmid, pREP41-Ub-GFP-SpCPS was digested with PstI and BamHI. A fragment containing the nmt1 promoter and the Ub–GFP–SpCPS ORF was recovered, and then cloned into the corresponding sites of pREP42.

pAU/nmt41-RFP-Ptn1 was constructed as follows: codon usage of RFP (red fluorescent protein) was optimized for Sch. pombe to generate pRFPm1-2 by GENEART. The attenuated nmt1 promoter from pREP41, the RFP ORF from pRFPm1-2 and the ptn1 ORF from genomic DNA were amplified by PCR, digested with XhoI and EcoRI (nmt1 promoter), EcoRI and BamHI (RFP) and BamHI and NotI (ptn1), respectively, and then sequentially cloned into the corresponding sites of pAU-SK.

pAL(map3-GFP), a multicopy plasmid for expression of Map3–GFP, was obtained from Dr C. Shimoda (Morishita et al., 2002).

Vacuole staining.

Vacuolar membranes were labelled with FM4-64 (Vida & Emr, 1995). Cells were grown to exponential phase in YES medium at 30 °C and 500 μl cells was then incubated in medium containing 8 μM FM4-64 for 30 min at 30 °C. The cells were then centrifuged at 13 000 g for 1 min, washed by resuspending in YES to remove free FM4-64 and collected by centrifugation at 13 000 g for 1 min. Cells were then resuspended in YES and incubated for 90 min at 30 °C before microscopic observation. Stained cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope (model BX-60; Olympus).

Internalization assay using FM4-64.

Exponentially growing cells in YES medium were incubated with 16 μM FM4-64 on ice for 30 min to label the plasma membrane. Cells were then washed with ice-cold fresh medium to remove excess dye, and resuspended in ice-cold fresh medium. Cells were then incubated at 30 °C and a small aliquot was withdrawn after adequate incubation for microscopic observation.

Analysis of fluid-phase endocytosis.

Fluid-phase endocytosis was observed microscopically after cells were treated with Lucifer Yellow CH (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining with Lucifer Yellow CH was performed as described previously (Murray & Johnson, 2001). Briefly, 1 ml of exponentially growing cells in YES medium was collected by centrifugation, washed twice with fresh medium and resuspended in 0.5 ml YES medium containing 5 mg ml−1 Lucifer Yellow CH. Cells were incubated at 30 °C for 60 min with shaking and then washed three times with fresh medium. Labelled cells were then subjected to microscopic observation.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Cells were observed with an Olympus BX-60 fluorescence microscope using a U-MGFPHQ filter set (for GFP), U-MWBV filter set (for Lucifer Yellow CH) or U-MIG filter set (for RFP and FM 4-64; all filters Olympus). Images were captured with a SenSys Cooled CCD camera using MetaMorph (Roper Scientific), and were saved as Adobe Photoshop files on a Macintosh G4 computer.

RESULTS

The sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ genes encode homologues of Sac. cerevisiae class E Vps proteins

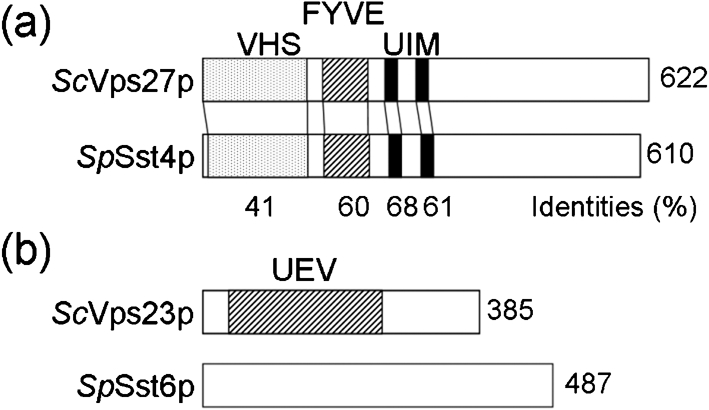

In a previous study, sst4 and sst6 were identified as vps27/SPAC19A8.05c and SPAC11H11.01, respectively (Onishi et al., 2003). The sst4/vps27+ gene was found to be homologous to the Sac. cerevisiae VPS gene, VPS27, and sst6+ was similar to VPS23. Overall, Sac. cerevisiae Vps27p and Sch. pombe Sst4/Vps27p are similar in size (622 and 610 aa, respectively) and share approximately 50 % amino acid sequence similarity (Fig. 1a). In addition, both Vps27p and Sst4/Vps27p have similar predicted domain structures, having VHS (Vps27p, Hrs, and STAM), FYVE and UIM (ubiquitin-interacting motif) domains. The VHS domain was originally identified in a database screen of sequences in signal transduction proteins (Lohi et al., 2002). The VHS domain of Vps27p appears to play a role in Hse1p-associated endocytosis of a selected set of receptor molecules (Shih et al., 2002; Bilodeau et al., 2002). The FYVE domain of Sac. cerevisiae Vps27p has been shown to bind to liposomes that contain PtdIns-3-P, but not to liposomes that contain other phosphoinositides, indicating that the FYVE domain of Vps27p specifically binds to PtdIns-3-P in vitro (Burd & Emr, 1998). The UIM domain was determined based on sequences identified in the subunit of the 26S proteasome that interacts with polyubiquitin (Young et al., 1998).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ genes. (a) Domain structures of the Sch. pombe Sst4/Vps27 (SpSst4p) and Sac. cerevisiae Vps27 (ScVps27p) proteins. The shaded, hatched and closed boxes indicate the VHS, FYVE and UIM domains, respectively. (b) Domain structures of the Sch. pombe Sst6 (SpSst6p) and Sac. cerevisiae Vps23 (ScVps23p) proteins. ScVps23p possesses a UEV domain (hatched), similar to the catalytic domain of the E2 UBC enzyme, but SpSst6p has no domains defined by the SMART or Pfam databases.

Although the amino acid sequence of Sst6 revealed a relatively low overall level of similarity with Sac. cerevisiae Vps23p, the 60 C-terminal amino acids are conserved with mammalian TSG101 (Babst et al., 2000; Bishop & Woodman, 2001). The ubiquitin E2 variant (UEV) domains reside in the N-terminal regions of Vps23p and TSG101, and share homology with the catalytic domain of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (UBC). However, Vps23p and TSG101 are unlikely to catalyse ubiquitination because both proteins have substitutions for the cysteine residue that forms a reversible covalent bond with ubiquitin in E2 enzymes (Babst et al., 2000). Interestingly, the Sst6 protein does not contain a UEV domain (Fig. 1b).

Disruption of sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ results in moderate vacuolar protein sorting defects

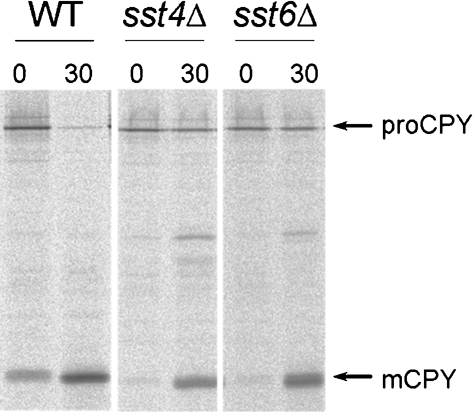

To determine whether the sst4/vps27+ and sst6+ genes are required for vacuolar protein trafficking in Sch. pombe, sst4/vps27 and sst6 null mutants were constructed in a wild-type (WA8) background. We have previously reported the isolation and characterization of a vacuolar marker protein, a carboxypeptidase from Sch. pombe (Cpy1p) (Tabuchi et al., 1997). To determine whether Sch. pombe Sst4/Vps27p and Sst6p are required for vacuolar protein transport, the sorting of Cpy1p in the sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants was analysed by pulse–chase experiments. During synthesis, Cpy1p undergoes a characteristic modification, a change in its apparent molecular mass. After the 15 min pulse period, the endoplasmic reticulum- and Golgi-specific precursor form (proCPY) and a small amount of the vacuole-specific mature form (mCPY) were labelled in wild-type cells, and after the 30 min chase, all Cpy1p was transported to the vacuole and matured, indicating that Cpy1p was properly delivered to the vacuole (Fig. 2). The sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ null mutants showed a sorting defect for Cpy1p. After the 30 min chase, approximately 30 % of the proCPY was still detected, while most of the remaining Cpy1p was processed to the mature form in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells, indicating that it had been transported to a compartment containing active vacuolar hydrolases (Fig. 2). Colony blot assay indicated that a fraction of CPY was secreted into the medium in these mutants (Fig. 7a). These results indicate that the Sst4/Vps27 and Sst6 proteins are required for efficient delivery of Cpy1p to the vacuole in Sch. pombe.

Fig. 2.

Processing of SpCPY in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells. Wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) and sst6Δ cells were pulse-labelled with Express-35S (NEN) for 15 min at 30 °C, and chased for 30 min. The immunoprecipitates were separated on an SDS polyacrylamide gel (10 %). Autoradiograms of the fixed dried gels are shown. The positions of proCPY (110 kDa) and mature CPY (mCPY, 32 kDa) are indicated.

Fig. 7.

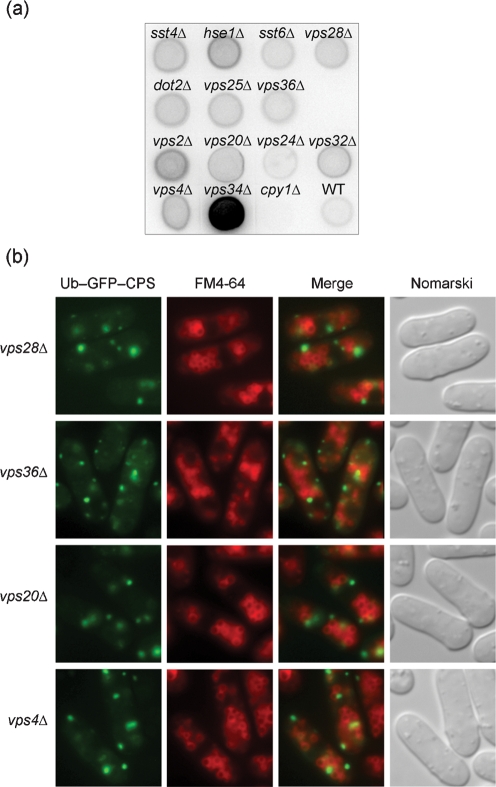

Phenotypic analyses of various class E mutants. (a) Secretion of CPY was determined using a colony blot assay. The membranes were subjected to immunoblotting with rabbit anti-CPY. Wild-type (WT), vps34Δ (positive control) and MTD2 (cpy1Δ, negative control) are included for comparison. (b) Localization of Ub–GFP–SpCPS was compared with vacuolar staining of FM4-64. Cells were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 6(a). vps28Δ, vps36Δ and vps20Δ are representative of ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II and ESCRT-III, respectively. All other mutants exhibited the same patterns of fluorescence.

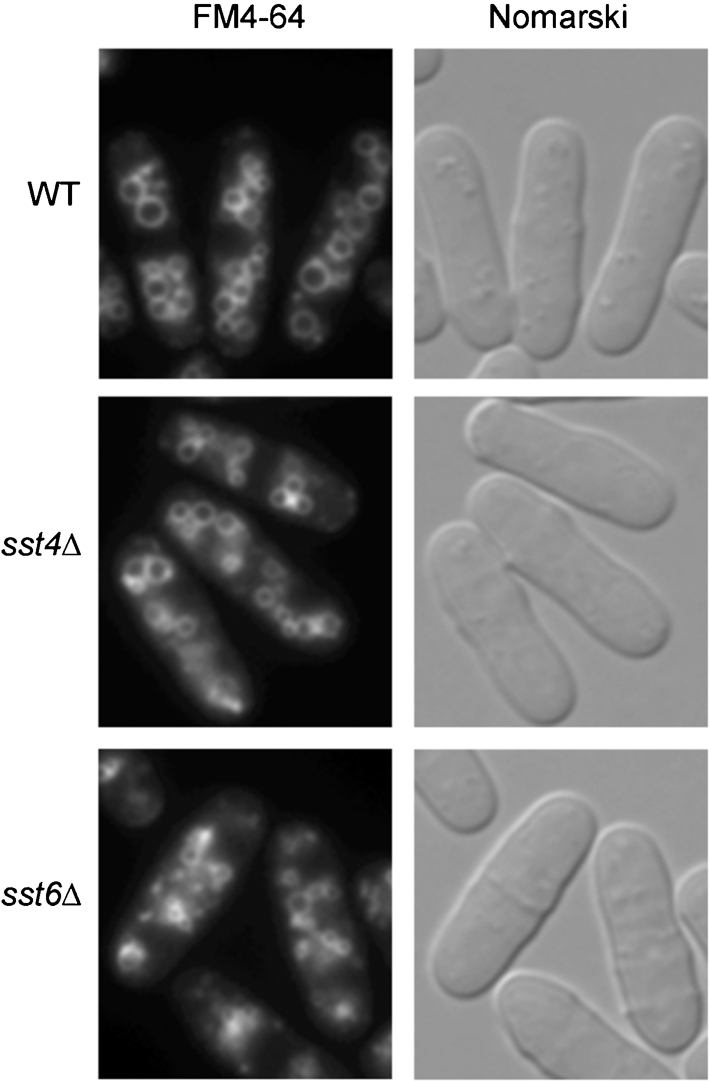

Vacuolar morphology and endocytosis in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ

Sac. cerevisiae class E vps mutants accumulate FM4-64 in the vacuolar membrane and class E compartment adjacent to the vacuole (Raymond et al., 1992; Vida & Emr, 1995), and are defective in endocytosis (Piper et al., 1995). Staining with FM4-64 revealed that vacuoles in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ were mostly similar in size to wild-type, but that some of them were smaller (Fig. 3). They were nearly normal compared to those found in ypt7Δ, which has fragmented vacuoles because of the lack of vacuolar fusion (Iwaki et al., 2004). Structures corresponding to class E compartment were indistinguishable, because of the size and number of vacuoles. However, transmission electron microscopy revealed that class E vps mutants accumulated aberrant membranous structures (Supplementary Fig. S1, available with the online version of this paper).

Fig. 3.

Vacuolar morphology in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants. Vacuoles of wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) and sst6Δ cells were stained with FM4-64.

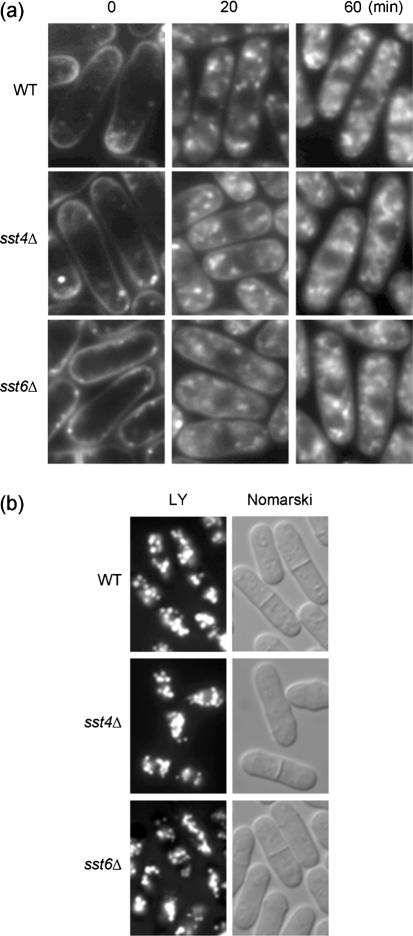

To examine the effect of the loss of Sst4/Vps27p and Sst6p on the endocytic pathway, sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells were labelled with FM4-64 on ice, followed by incubation at 30 °C. This fluorescent dye initially stains the plasma membrane and is then internalized and delivered to the vacuolar membrane in a time-, energy- and temperature-dependent manner (Vida & Emr, 1995). After labelling of wild-type, sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells with FM4-64 for 30 min on ice, the dye stained the plasma membrane and septa, and several punctate patches were observed near the plasma membrane (Fig. 4a). Following incubation at 30 °C, the FM4-64 dye was gradually transported out of the peripheral membranes, and the patches were then observed to be distributed in the cytoplasm. After incubation at 30 °C for 20 min, FM4-64 predominantly labelled the prevacuolar compartments. Staining of the plasma membrane was not detected in wild-type cells. In sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells, we observed pronounced staining of the plasma membranes and prevacuolar compartments (Fig. 4a). After a 60 min chase at 30 °C, FM4-64 was transported in part to the vacuolar membrane, such that the staining patterns of the sstΔ mutants could not be distinguished from those observed in wild-type. These results demonstrate that the FM4-64 dye was slowly internalized in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells.

Fig. 4.

Analyses of endocytosis. (a) Time-course of FM4-64 internalization via the endocytic pathway. Living wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) or sst6Δ cells were labelled with 16 μM FM4-64 on ice for 30 min and then incubated at 30 °C for the indicated periods. (b) Accumulation of Lucifer Yellow CH. Wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) or sst6Δ cells were incubated for 60 min at 30 °C in YES medium containing 5 mg ml−1 Lucifer Yellow CH (LY). Cells were then washed and observed by fluorescence microscopy.

To determine whether sstΔ cells are also defective fluid-phase endocytosis, accumulation of Lucifer Yellow CH was observed. Wild-type, sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells were incubated in Lucifer Yellow CH for 1 h at 30 °C. Vacuolar accumulation of Lucifer Yellow CH was observed in wild-type as expected, but also in the sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that Sst proteins are not essential for fluid-phase endocytosis in Sch. pombe. Vacuoles containing Lucifer Yellow CH in sstΔ cells were similar to those in wild-type, supporting the view that these mutants have nearly normal vacuoles.

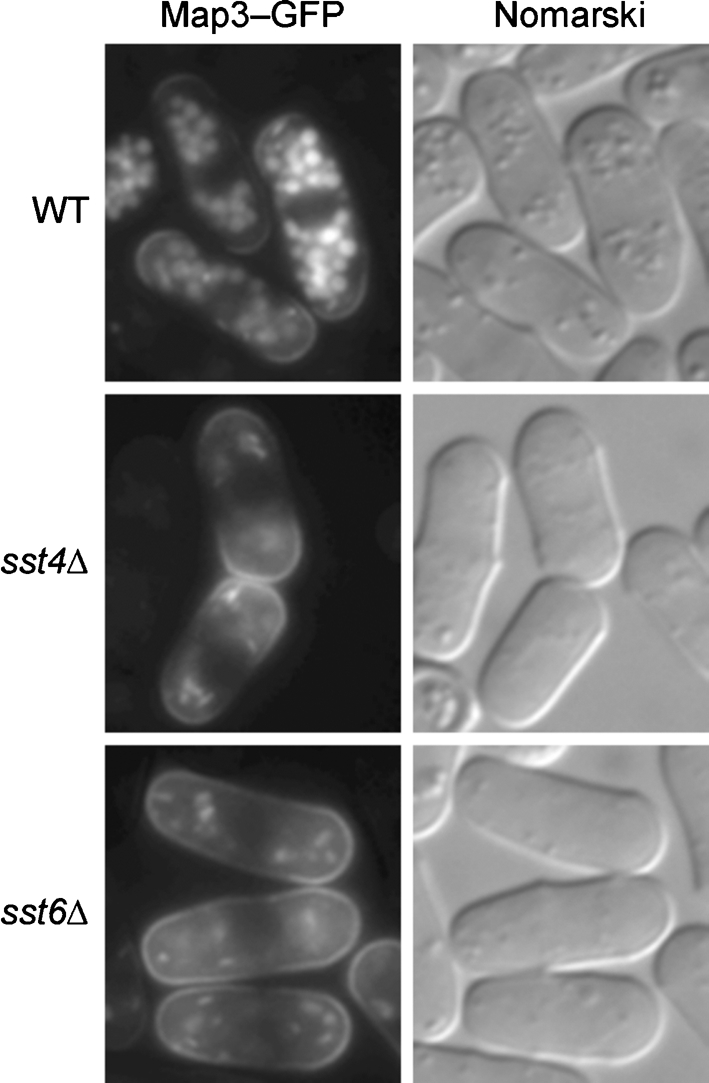

Map3p is the mating pheromone M-factor receptor expressed in h+ strains. The internalization of Map3–GFP occurs in homothallic cells that do not undergo successful conjugation when subjected to nitrogen starvation (Hirota et al., 2001). Map3–GFP was expressed under the control of the map3 promoter on a multicopy plasmid, resulting in overexpression. Wild-type homothallic cells overexpressing Map3–GFP formed aggregates even when not starved for nitrogen (data not shown), probably because of the increased mating efficiency. Map3–GFP was found in the vacuoles and partly on the cell surface of unconjugated wild-type cells (Fig. 5), suggesting that Map3–GFP was internalized and degraded. Map3–GFP-overexpressing sst4/vps27Δ or sst6Δ cells did not form aggregates, and Map3–GFP localized mostly on the cell surface (Fig. 5). This observation suggests that internalization of plasma membrane proteins might be inhibited in these mutants.

Fig. 5.

Localization of Map3–GFP in homothallic cells. Cells containing pAL(map3-GFP) were grown in 5 ml MM medium without Leu for 20 h, and then observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Sst4/Vps27p and Sst6p are required for MVB sorting

CPS is one of the most studied MVB cargo proteins, and the Ub–GFP–CPS fusion protein has been used as a marker for MVB sorting in Sac. cerevisiae (Katzmann et al., 2004). To test the important question of whether the MVB is found in Sch. pombe and whether Sst4/Vps27p and Sst6p play significant roles in MVB sorting, we searched the Sch. pombe genome database for a CPS homologue. One CPS homologue, SPAC24C9.08 (SpCPS) was found and, therefore, GFP–SpCPS was constructed and expressed, because GFP–CPS is also known as a good indicator of the MVB in Sac. cerevisiae (Odorizzi et al., 1998). Ubiquitin chains are added to lysine residues, and K8 of the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain is known to be ubiquitinated in Sac. cerevisiae CPS (Katzmann et al., 2001). SpCPS has four lysine residues in the putative N-terminal cytoplasmic domain, K16, K19, K32 and K33. Ubiquitin chains may be added to one or more of these residues. However, GFP–SpCPS was not effectively sorted into vacuoles even in wild-type. It is possible that GFP may inhibit ubiquitination of SpCPS or interfere with normal interaction with Sst4/Vps27p.

In an attempt to identify an MVB marker protein, SPBC713.07c was found to be a homologue of Sac. cerevisiae Phm5p (Supplementary Fig. S2a, available with the online version of this paper), which is also transported into vacuoles via the MVB pathway (Reggiori & Pelham, 2001). A GFP–SPBC713.07c fusion protein was expressed in wild-type cells, but the fusion protein was not localized in the vacuoles (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

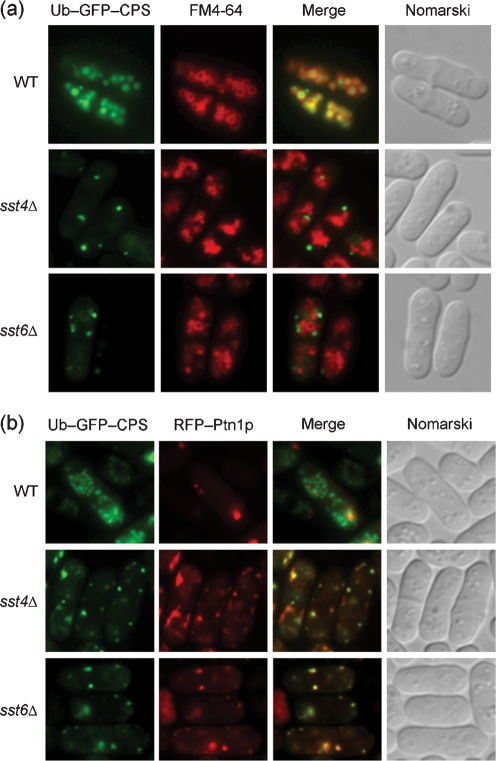

Therefore, a single ubiquitin molecule was fused to the N-terminus of GFP–SpCPS, and Ub–GFP–SpCPS was expressed in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants (Fig. 6a). Wild-type cells expressing Ub–GFP–SpCPS exhibited a vacuolar pattern of fluorescence corresponding to the staining pattern of FM4-64, indicating that it was sorted into MVB vesicles and transported to the vacuoles. Ub–GFP–SpCPS exhibited punctate fluorescence and separated from vacuoles in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Localization of Ub–GFP–SpCPS in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells. (a) Sorting of Ub–GFP–SpCPS into vacuoles is inhibited in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ. Cells containing pREP41-Ub-GFP-SpCPS were grown in MM medium without Leu and thiamine for 20 h, after which vacuoles were labelled with FM4-64. Wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) and sst6Δ cells are shown. (b) Ub–GFP–SpCPS is trapped in endosomes in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ cells. Cells expressing Ub–GFP–SpCPS and RFP–Ptn1p were grown in MM medium without Leu, Ura and thiamine for 20 h. Wild-type (WT), sst4/vps27Δ (sst4Δ) and sst6Δ cells are shown.

PtdIns 3,4,5-triphosphate 3-phosphatase, Ptn1p, is reported to accumulate on the endosome (Mitra et al., 2004). To clarify localization of Ub–GFP–SpCPS, RFP (red fluorescent protein) was fused to the N-terminus of Ptn1p and co-expressed under an attenuated nmt1 promoter. In wild-type cells, these two proteins showed distinct patterns of fluorescence (Fig. 6b). Most of the fluorescent dots of Ub–GFP–SpCPS merged with RFP–Ptn1p in sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants (Fig. 6b), suggesting that it localizes primarily to endosomes, and that sorting into MVB is inhibited.

Mutations in putative class E vps genes also cause MVB sorting defects

Since VPS23 and VPS27 are classified as class E vps genes in Sac. cerevisiae (Raymond et al., 1992), the Sch. pombe homologues were deleted and the resultant mutants tested for defects in CPY maturation and MVB sorting. Disruptants of putative class E vps genes, consisting of ESCRT machinery, were constructed (Table 2). While VPS37 homologues were not found in the fission yeast genome, a VPS22 homologue, dot2+, has been reported to be a homologue of the human transcription factor EAP30, which negatively regulates meiotic spindle pole body maturation (Jin et al., 2005). Disruption of all of these vps genes resulted in mild defects in CPY maturation (data not shown), and missorting of a fraction of CPY into the medium (Fig. 7a), as observed for the sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants. A disruption mutant of cpy1 encoding CPY, cpy1Δ, was used as a negative control (Tabuchi et al., 1997). vps34Δ was used as positive control secreting strong levels of CPY (Cheng et al., 2002). Localization analysis of Ub–GFP–SpCPS was also undertaken for these mutants (Fig. 7b). None was found able to sort Ub–GFP–SpCPS into vacuoles, suggesting that these genes are required for sorting into the MVB.

Table 2.

ESCRT complexes and deubiquitinating enzyme homologues in Sch. pombe

| Complex | Homologue* | Sch. pombe | E-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vps27/Hse1 | VPS27 | sst4/vps27+/SPAC19A8.05 | 7.8e–61 |

| HSE1 | hse1+/SPBC1734.08 | 6.3e–59 | |

| ESCRT-I | VPS23/STP22 | sst6+/SPAC11H11.01 | 2.5e–07 |

| VPS28 | vps28+/SPAC1B3.07 | 1.3e–35 | |

| VPS37 | --- | ||

| ESCRT-II | VPS22/SNF8 | dot2+/SPBC651.05c | 2.3e–36 |

| VPS25 | vps25+/SPBC4B4.06 | 6.3e–16 | |

| VPS36 | vps36+/SPBC3B9.09 | 2.5e–27 | |

| ESCRT-III | VPS2/DID4 | vps2+/SPAC4F8.01 | 2.2e–49 |

| VPS20 | vps20+/SPBC215.14c | 1.3e–19 | |

| VPS24 | vps24+/SPAC9E9.14 | 1.1e–27 | |

| VPS32/SNF7 | vps32+/SPBC215.14 | 2.3e–38 | |

| Vps4 | VPS4 | vps4+/SPAC2G11.06 | 2.1e–145 |

| Deubiquitinating enzyme | hAMSH | sst2+/SPAC19B12.10 | 2.7e–56 |

| DOA4 | ubp1+/SPCC16A11.12c | 3.9e–50 | |

| ubp4+/SPBC18H10.08c | 2.6e–49 | ||

| ubp12+/SPCC1494.05 | 2.7e–56 |

*Sac. cerevisiae homologues are indicated with the exception of human AMSH (hAMSH).

†The fission yeast proteins were identified by screening the Sch. pombe genome database for new homologues of the known Sac. cerevisiae proteins using the blast program for sequence alignments (http://www.genedb.org/genedb/pombe/blast.jsp). Probability scores are shown as E-values. For Sst2p, the human AMSH protein sequence was used as a query.

sst2+ is a class E vps gene in fission yeast

While recent studies found that a deubiquitinating enzyme, AMSH, is also essential for the MVB pathway in mammals (McCullough et al., 2004; Agromayor & Martin-Serrano, 2006), it was not found in Sac. cerevisiae, which has a different deubiquitinating enzyme, Doa4p (Amerik et al., 2000). Sch. pombe has an AMSH homologue, previously identified as sst2+(Onishi et al., 2003). Apparent PXXP motifs, required for interaction with STAM (Tanaka et al., 1999), were not found in Sst2p, although these proteins share 31 % identity.

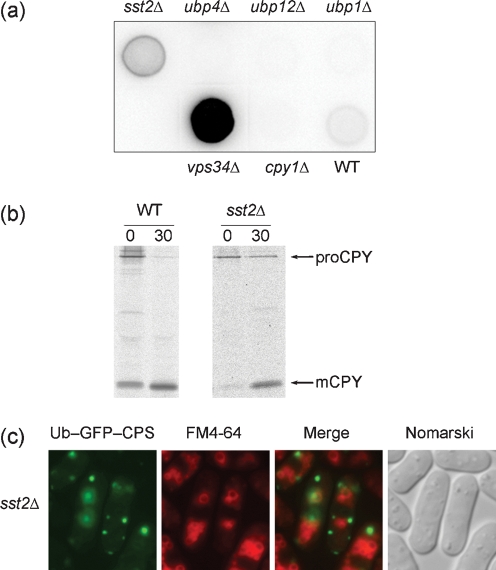

The Sac. cerevisiae doa4 mutant was found capable of normal CPY delivery to vacuoles (Amerik et al., 2000), but exhibited aberrant sorting into the MVB (Reggiori & Pelham, 2001), indicating a contribution to the MVB pathway. While ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases in Sch. pombe share sequence similarity with one another, three proteins exhibited relatively high homology with Doa4p: Ubp1p/SPCC16A11.12c, Ubp4p/SPBC18H10.08c and Ubp12p/SPCC1494.05 (Table 2). Ubp4p has been annotated as a Doa4p homologue in the genome database. Disruption mutants of these four genes encoding putative deubiquitinating enzymes were constructed. While the sst2Δ mutant was able to secrete CPY (Fig. 8a), it exhibited defects in CPY maturation (Fig. 8b) and impaired sorting into the MVB (Fig. 8c). CPY secretion and mislocalization of Ub–GFP–SpCPS were not detected in the ubp1Δ, ubp4Δ, or ubp12Δ mutants (Fig. 8a), indicating that disruption of these ubp genes did not result in a class E phenotype. However, a contribution of Ubp proteins to MVB sorting cannot be ruled out, because a ubiquitin-fused marker protein is normally transported into vacuoles in a Sac. cerevisiae doa4Δ mutant (Reggiori & Pelham, 2001).

Fig. 8.

Characterization of sst2+. (a) Secretion of CPY was determined using a colony blot assay as described in the legend to Fig. 4(a). Wild-type (WT), vps34Δ and MTD2 (cpy1Δ) are included for comparison. (b) Processing of SpCPY in the sst2Δ mutant. sst2Δ cells were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The positions of proCPY (110 kDa) and mature CPY (mCPY, 32 kDa) are indicated. (c) Localization of Ub–GFP–SpCPS in the sst2Δ mutant. Cells were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 6(a).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that sorting defects in the sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ Sch. pombe mutants are relatively modest; 30 % or less of CPY was not processed to the mature form (Fig. 2). The modest sorting defect, together with the delay of transport of FM4-64 to the vacuolar membranes (Fig. 4), suggests that sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ mutants are not completely defective in vacuolar transport, but rather exhibit a kinetic defect in transport out of the prevacuolar endosome-like compartments. Functional conservation of these proteins was expected from homology to budding yeast homologues. In agreement with this idea, a biosynthetic MVB cargo, Ub–GFP–SpCPS, was trapped in the endosomes in these mutants (Fig. 6). Transmission electron microscopy revealed that class E vps mutants accumulated aberrant membranous structures (Supplementary Fig. S1, available with the online version of this article), although we have not confirmed that these compartments correspond to Sac. cerevisiae class E compartments.

The Sch. pombe Sst4/Vps27 protein contains a UIM domain, similar to Sac. cerevisiae Vps27p (Fig. 1a). It was recently shown that the UIM domain of Sac. cerevisiae Vps27p binds to mono-ubiquitin through Ile44 of ubiquitin (Shih et al., 2002). Cell-surface transmembrane proteins such as G-protein-coupled receptors and transporters in Sac. cerevisiae are modified with ubiquitin in response to ligand binding. Ubiquitination serves to trigger rapid internalization and degradation of these proteins in the vacuole (Hicke, 1999). Several transmembrane proteins, including CPS and Phm5p, which are delivered from the Golgi to the endosome, are also ubiquitinated in Sac. cerevisiae (Reggiori & Pelham, 2001). The UIM domain of Sst4/Vps27p seems to be required for efficient sorting of cargo from both the biosynthetic and the endocytic pathways destined for delivery to the vacuole in Sch. pombe. In contrast to the Sst4/Vps27 protein, the Sch. pombe Sst6 protein lacks the UEV domain, which in Sac. cerevisiae Vps23p and in mammalian TSG101 has been shown to bind ubiquitin (Babst et al., 2000; Katzmann et al., 2001). The UEV domain of Vps23p is required for ESCRT-I to bind ubiquitin in vitro (Katzmann et al., 2001). Our results show that Sch. pombe Sst6p is required for the vacuolar protein sorting pathway and for MVB sorting. Therefore, the UEV domain is not essential for Sst6p function. Further analysis will be required to determine whether Sst6p forms a larger protein complex and whether Sst6p can bind to ubiquitin in the absence of the UEV domain.

We also found that other class E Vps proteins are required for maturation of CPY and sorting into MVBs (Fig. 7), indicating that the roles of class E Vps proteins are conserved in fission yeast. However, there are differences between fission yeast and budding yeast. Sch. pombe has an AMSH homologue, Sst2p, which is not found in Sac. cerevisiae. Lack of Sst2p resulted in a phenotype similar to that exhibited by the sst4/vps27Δ mutant and by other class E mutants (Fig. 8), suggesting that Sst2p may be a component of the ESCRT complex. Sst2p might play a crucial role for endosomal function, such as regulation of MVB sorting through deubiquitination of ubiquitinated ESCRT proteins. Mammalian Hrs and STAM are ubiquitinated proteins (Katz et al., 2002; Polo et al., 2002), raising the possibility that Sst4/Vps27p and Hse1p might be ubiquitinated and then become substrates for Sst2p. blast searches using Sch. pombe Ubp proteins as the query sequence indicated that Ubp4p is the most plausible candidate of a Doa4p homologue in Sch. pombe, as annotated by the genome database. It remains to be elucidated whether Ubp4p contributes to the deubiquitination of MVB cargo and the regulation of endosomal functions through protein deubiquitination on the endosomes. In addition, homologues of Vps37p could not be found in the fission yeast genome by blast searches (Takegawa et al., 2003). While recent experimental interaction studies have identified the human orthologues of VPS37 (Bache et al., 2004; Eastman et al., 2005), the low levels of sequence identity were not sufficient to identify these homologues based on sequence alone. If Sch. pombe possesses a molecule with a function similar to that of Vps37p, its amino acid sequence will differ significantly from that of the Sac. cerevisiae and human Vps37ps.

As of this writing, there are few reports on the internalization and ubiquitination of cell-surface transmembrane proteins in Sch. pombe. One candidate molecule for an MVB cargo is the M-factor receptor Map3p. However, it has been already shown that internalization of Map3p is independent of ubiquitin (Hirota et al., 2001). Our results indicate that sst4/vps27Δ and sst6Δ exhibit impaired internalization of Map3–GFP prior to MVB sorting (Fig. 4). Interestingly, depletion of ESCRT-II did not influence endocytosis of a mammalian EGFR (Bowers et al., 2006). Our results show that sorting of biosynthetic MVB cargo is dependent on ESCRT-II in fission yeast, while it remains to be determined whether the endocytic MVB pathway depends on ESCRT-II or not. In order to address this question, it is essential to identify endocytic MVB marker proteins. We are currently examining the roles of ubiquitination with respect to the process of internalization of cell-surface transmembrane proteins in Sch. pombe. Future analyses are likely to provide important insights into the molecular details of MVB formation as well as ubiquitin-dependent protein trafficking in Sch. pombe cells.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs Masayuki Yamamoto, Taro Nakamura and Chikashi Shimoda for providing Sch. pombe strains and plasmids, and Naotaka Tanaka for critically reading the manuscript. This work was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, and the Project for Development of a Technological Infrastructure for Industrial Bioprocesses on R&D of New Industrial Science and Technology Frontiers by the Ministry of Economy, Trade & Industry (METI), as supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

Abbreviations

AMSH, associated molecule with the SH3 domain of STAM

CPS, carboxypeptidase S

CPY, carboxypeptidase Y

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor

ESCRT, endosomal sorting complex required for transport

GFP, green fluorescent protein

MVB, multivesicular body

PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol

RFP, red fluorescent protein

sst, suppressors of sterility in ste12

Ub, ubiquitin

UBC, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes

UBPY, ubiquitin isopeptidase Y

UEV, ubiquitin E2 variant

UIM, ubiquitin-interacting motif

VHS, Vps27p, Hrs and STAM

Vps, vacuolar protein sorting

Footnotes

Supplementary methods, electron micrographs and fusion protein figures are available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Agromayor, M. & Martin-Serrano, J. (2006). Interaction of AMSH with ESCRT-III and deubiquitination of endosomal cargo. J Biol Chem 281, 23083–23091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfa, C., Fantes, P., Hyams, J., McLeod, M. & Warbrick, E. (1993). Experiments with Fission Yeast: a Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- Alwan, H. A. J. & van Leeuwen, J. E. M. (2007). UBPY-mediated EGFR deubiquitination promotes EGFR degradation. J Biol Chem 282, 1658–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerik, A. Y., Nowak, J., Swaminathan, S. & Hochstrasser, M. (2000). The Doa4 deubiquitinating enzyme is functionally linked to the vacuolar protein-sorting and endocytic pathways. Mol Biol Cell 11, 3365–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst, M. (2005). A protein's final ESCRT. Traffic 6, 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst, M., Sato, T. K., Banta, L. M. & Emr, S. D. (1997). Endosomal transport function in yeast requires a novel AAA-type ATPase, Vps4p. EMBO J 16, 1820–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst, M., Wendland, B., Estepa, E. J. & Emr, S. D. (1998). The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J 17, 2982–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst, M., Odorizzi, G., Estepa, E. J. & Emr, S. D. (2000). Mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) and the yeast homologue, Vps23p, both function in late endosomal trafficking. Traffic 1, 248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst, M., Katzmann, D. J., Estepa-Sabal, E. J., Meerloo, T. & Emr, S. D. (2002). ESCRT-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for MVB sorting. Dev Cell 3, 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache, K. G., Slagsvold, T., Cabezas, A., Rosendal, K. R., Raiborg, C. & Stenmark, H. (2004). The growth-regulatory protein HCRP1/hVps37A is a subunit of mammalian ESCRT-I and mediates receptor down-regulation. Mol Biol Cell 15, 4337–4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta, L. M., Robinson, J. S., Klionsky, D. J. & Emr, S. D. (1988). Organelle assembly in yeast: characterization of yeast mutants defective in vacuolar biogenesis and protein sorting. J Cell Biol 107, 1369–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau, P. S., Urbanowski, J. L., Winistorfer, S. C. & Piper, R. C. (2002). The Vps27p-Hse1p complex binds ubiquitin and mediates endosomal protein sorting. Nat Cell Biol 4, 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, N. & Woodman, P. (2001). TSG101/mammalian VPS23 and mammalian VPS28 interact directly and are recruited to VPS4-induced endosomes. J Biol Chem 276, 11735–11742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, K. & Stevens, T. H. (2005). Protein transport from the late Golgi to the vacuole in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1744, 438–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, K., Piper, S. C., Edeling, M. A., Gray, S. R., Owen, D. J., Lehner, P. J. & Luzio, J. P. (2006). Degradation of endocytosed epidermal growth factor and virally ubiquitinated major histocompatibility complex class I is independent of mammalian ESCRT II. J Biol Chem 281, 5094–5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd, C. G. & Emr, S. D. (1998). Phosphatidylinositol (3)-phosphate signaling mediated by specific binding to RING FYVE domains. Mol Cell 2, 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H., Sugiura, R., Wu, W., Fujita, M., Lu, Y., Sio, S. O., Kawai, R., Takegawa, K., Shuntoh, H. & Kuno, T. (2002). Role of the Rab GTP-binding protein Ypt3 in the fission yeast exocytic pathway, and its connection to calcineurin function. Mol Biol Cell 13, 2963–2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupré, S. & Haguenauer-Tsapis, R. (2001). Deubiquitination in the endocytic pathway of yeast plasma membrane proteins: crucial role of Doa4p ubiquitin isopeptidase. Mol Cell Biol 21, 4482–4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, S. W., Martin-Serrano, J., Chung, W., Zang, T. & Bieniasz, P. D. (2005). Identification of human VPS37C, a component of endosomal sorting complex required for transport-I important for viral budding. J Biol Chem 280, 628–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke, L. (1999). Gettin' down with ubiquitin: turning off cell-surface receptors, transporters and channels. Trends Cell Biol 9, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, K., Tanaka, K., Watanabe, Y. & Yamamoto, M. (2001). Functional analysis of the C-terminal cytoplasmic region of the M-factor receptor in fission yeast. Genes Cells 6, 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki, T. & Takegawa, K. (2004). A set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene disruption in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68, 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki, T., Tanaka, N., Takagi, H., Giga-Hama, Y. & Takegawa, K. (2004). Characterization of end4+, a gene required for endocytosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 21, 867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., Mancuso, J. J., Cronembold, D. & Cande, W. Z. (2005). The fission yeast homolog of the human transcription factor EAP30 blocks meiotic spindle pole body amplification. Dev Cell 9, 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M., Shtiegman, K., Tal-Or, P., Yakir, L., Mosesson, Y., Harari, D., Machluf, Y., Asao, H., Jovin, T. & other authors (2002). Ligand-independent degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor involves receptor ubiquitylation and Hgs, an adaptor whose ubiquitin-interacting motif targets ubiquitylation by Nedd4. Traffic 3, 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann, D. J., Babst, M. & Emr, S. D. (2001). Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 106, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann, D. J., Sarkar, S., Chu, T., Audhya, A. & Emr, S. D. (2004). Multivesicular body sorting: ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 is required for the modification and sorting of carboxypeptidase S. Mol Biol Cell 15, 468–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga, T., Onishi, M., Nakamura, Y., Hirata, A., Nakamura, T., Shimoda, C., Iwaki, T., Takegawa, K. & Fukui, Y. (2004). Sorting nexin homologues are targets of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in sporulation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells 9, 561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krsmanović, T., Pawelec, A., Sydor, T. & Kölling, R. (2005). Control of Ste6 recycling by ubiquitination in the early endocytic pathway in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 16, 2809–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohi, O., Poussu, A., Mao, Y., Quiocho, F. & Lehto, V.-P. (2002). VHS domain – a longshoreman of vesicle lines. FEBS Lett 513, 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, J., Clague, M. J. & Urbé, S. (2004). AMSH is an endosome-associated ubiquitin isopeptidase. J Cell Biol 166, 487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, R. K., Dove, S. K., Cooke, F. T., Painter, G. F., Holmes, A. B., Shisheva, A., Ohya, Y., Parker, P. J. & Michell, R. H. (1999). Complementation analysis in PrdInsP kinase-deficient yeast mutants demonstrates that Schizosaccharomyces pombe and murine Fab1p homologues are phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinases. J Biol Chem 274, 33905–33912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, P., Zhang, Y., Rameh, L. E., Ivshina, M. P., McCollum, D., Nunnari, J. J., Hendricks, G. M., Kerr, M. L., Field, S. J. & other authors (2004). A novel phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)P3 pathway in fission yeast. J Cell Biol 166, 205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, E., Iura, T., Mukai, A., Yoshimori, T., Kitamura, N. & Komada, M. (2005). Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor down-regulation by UBPY-mediated deubiquitination at endosomes. Mol Biol Cell 16, 5163–5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, E., Kobayashi, K., Yamamoto, A., Kitamura, N. & Komada, M. (2006). A deubiquitinating enzyme UBPY regulates the level of protein ubiquitination on endosomes. Traffic 7, 1017–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., Klar, A. & Nurse, P. (1991). Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol 194, 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, M., Morimoto, F., Kitamura, K., Koga, T., Fukui, Y., Maekawa, H., Yamashita, I. & Shimoda, C. (2002). Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase is required for the cellular response to nutritional starvation and mating pheromone signals in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells 7, 199–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, T. & Takegawa, K. (2004). A simple and efficient procedure for transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 21, 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. M. & Johnson, D. I. (2001). The Cdc42p GTPase and its regulators of Nrf1p and Scd1p are involved in endocytic trafficking in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem 276, 3004–3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T., Nakamura-Kubo, M., Hirata, A. & Shimoda, C. (2001). The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spo3+ gene is required for assembly of the forespore membrane and genetically interacts with psy1+-encoding syntaxin-like protein. Mol Biol Cell 12, 3955–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi, G., Babst, M. & Emr, S. D. (1998). Fab1p PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase function essential for protein sorting in the multivesicular body. Cell 95, 847–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, K., Okazaki, N., Kume, K., Jinno, S., Tanaka, K. & Okayama, H. (1990). High-frequency transformation method and library transducing vectors for cloning mammalian cDNAs by trans-complementation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res 18, 6485–6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, M., Nakamura, Y., Koga, T., Takegawa, K. & Fukui, Y. (2003). Isolation of suppressor mutants of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase deficient cells in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67, 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, R. C. & Luzio, J. P. (2001). Late endosomes: sorting and partitioning in multivesicular bodies. Traffic 2, 612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, R. C., Cooper, A. A., Yang, H. & Stevens, T. H. (1995). VPS27 controls vacuolar and endocytic traffic through a prevacuolar compartment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 131, 603–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo, S., Sigismund, S., Faretta, M., Guidi, M., Capua, M. R., Bossi, G., Chen, H., De Camilli, P. & Di Fiore, P. P. (2002). A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature 416, 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C. K., Howald-Stevenson, I., Vater, C. A. & Stevens, T. H. (1992). Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol Biol Cell 3, 1389–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori, F. & Pelham, H. R. B. (2001). Sorting of proteins into multivesicular bodies: ubiquitin-dependent and -independent targeting. EMBO J 20, 5176–5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, S. E., Banta, L. M., Kohrer, K., McCaffery, J. M. & Emr, S. D. (1996). Multilamellar endosome-like compartment accumulates in the yeast vps28 vacuolar protein sorting mutant. Mol Biol Cell 7, 985–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Row, P. E., Prior, I. A., McCullough, J., Clague, M. J. & Urbé, S. (2006). The ubiquitin isopeptidase UBPY regulates endosomal ubiquitin dynamics and is essential for receptor down-regulation. J Biol Chem 281, 12618–12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, S. C., Katzmann, D. J., Schnell, J. D., Sutanto, M., Emr, S. D. & Hicke, L. (2002). Epsins and Vps27p/Hrs contain ubiquitin-binding domains that function in receptor endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 4, 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetens, O., De Craene, J.-O. & André, B. (2001). Ubiquitin is required for sorting to the vacuole of the yeast general amino acid permease, Gap1. J Biol Chem 276, 43949–43957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga, M. & Hatakeyama, T. (2001). High efficiency transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe pretreated with thiol compounds by electroporation. Yeast 18, 1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga, M., Isobe, M. & Hatakeyama, T. (2000). Cryopreservation of competent intact yeast cells for efficient electroporation. Yeast 16, 889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi, M., Iwaihara, O., Ohtani, Y., Ohuchi, N., Sakurai, J., Morita, T., Iwahara, S. & Takegawa, K. (1997). Vacuolar protein sorting in fission yeast: cloning, biosynthesis, transport, and processing of carboxypeptidase Y from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Bacteriol 179, 4179–4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegawa, K., DeWald, D. B. & Emr, S. D. (1995). Schizosaccharomyces pombe Vps34p, a phosphatidylinositol-specific PI 3-kinase essential for normal cell growth and vacuole morphology. J Cell Sci 108, 3745–3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegawa, K., Iwaki, T., Fujita, Y., Morita, T., Hosomi, A. & Tanaka, N. (2003). Vesicle-mediated protein transport pathways to the vacuole in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell Struct Funct 28, 399–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N., Kaneko, K., Asao, H., Kasai, H., Endo, Y., Fujita, T., Takeshita, T. & Sugamura, K. (1999). Possible involvement of a novel STAM-associated molecule ‘AMSH’ in intracellular signal transduction mediated by cytokines. J Biol Chem 274, 19129–19135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, H. T. H., Connell, J. W., Brown, S. E., Thompson, A., Reid, E. & Sanderson, C. M. (2006). A systematic analysis of human CHMP protein interactions: additional MIT domain-containing proteins bind to multiple components of the human ESCRT III complex. Genomics 88, 333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida, T. A. & Emr, S. D. (1995). A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Biol 128, 779–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, V. & Hauser, M.-T. (2006). Exploring the ESCRTing machinery in eukaryotes. Trends Plant Sci 11, 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, P., Deveraux, Q., Beal, R. E., Pickart, C. M. & Rechsteiner, M. (1998). Characterization of two polyubiquitin binding sites in the 26 S protease subunit 5a. J Biol Chem 273, 5461–5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]