Abstract

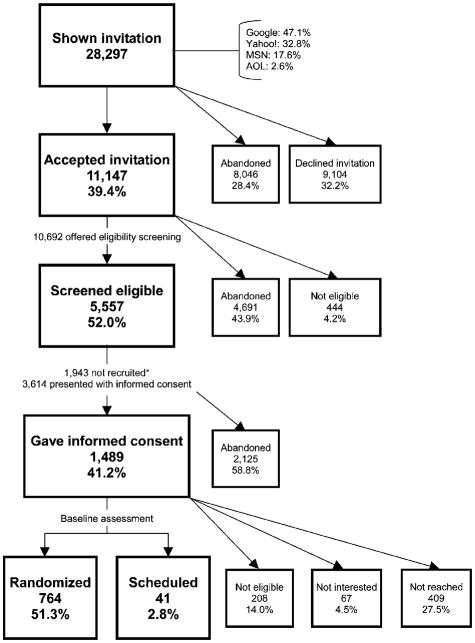

The Internet can deliver smoking cessation interventions to large numbers of smokers. Little is known about the feasibility, reach, or efficacy of Internet cessation interventions. Virtually no data exist on who enrolls in cessation programs or on differences between those who complete enrollment and those who do not. This paper reports recruitment and enrollment findings for the first 764 participants in an ongoing randomized controlled trial that tested the efficacy of a widely disseminated Internet smoking cessation service (www.QuitNet.com) alone and in conjunction with telephone counseling. Study participants were recruited through Internet search engines using an active user sampling protocol. During the first 16 weeks of the study, 28,297 individuals were invited. Of those, 11,147 accepted the invitation, 5,557 screened eligible, 3,614 were recruited, 1,489 provided online informed consent, and 764 were confirmed eligible and enrolled. Of those who were at least curious about a cessation trial (n=11,147), 6.9% enrolled. Of those who were eligible and recruited (n=3,614), 21.1% enrolled. Depending on the denominator selected, results suggest that 7% to 21% of smokers interested in cessation will enroll into a research trial. Internet recruitment provides unique challenges and opportunities for managing sample recruitment, analyzing subsamples to determine generalizability, and understanding the characteristics of individuals who participate in online research.

Background

The Internet holds great promise as a method to reach and treat smokers. The number of smokers seeking information online exceeds 8 million in the United States (Fox, 2005). There have been several studies of Internet-based smoking cessation treatment (Etter & Perneger, 2001; Feil, Noell, Lichtenstein, Boles, & McKay, 2003; Koo & Skinner, 2005; Stoddard et al., 2005; Strecher, Shiffman, & West, 2005). In addition to establishing the effectiveness of online cessation treatments, researchers also need to document the feasibility of online recruitment, and determine whether participants reached, recruited, and enrolled in a study via the Internet differ from other participant groups.

Several methods for recruiting smokers into Internet trials have been described (Lenert & Skoczen, 2002; Cobb, Graham, Stoddard, & Rabius, 2005b), including direct email and posts to online newsgroups, chat rooms, or Web sites. These methods have yielded widely variable response rates depending on the population sampled, the recruitment methodology, and the denominators selected and reported (Feil et al., 2003; Koo & Skinner, 2005; Stoddard et al., 2005; Strecher et al., 2005). This variability highlights an important methodological consideration in conducting Internet research: To estimate the reach of a recruitment approach and the generalizability of results, it is important to document the target population, the number exposed to recruitment, the number who respond, the number eligible, and the number who actually participate (Abrams et al., 1996; Dzewaltowski, Glasgow, Klesges, Estabrooks, & Brock, 2004). In the majority of Internet studies cited above, these data are not reported or not clear. This information also is important if researchers are to understand the characteristics of smokers and the barriers they may encounter when responding to research opportunities on the Internet.

One mechanism for online recruitment, “active user interception sampling,” intercepts Internet users while they surf the Internet and replaces the expected page with a study invitation (Kaczmirek & Neubarth, 2005). In contrast to the methods reported in other Internet studies, this approach recruits Internet users in accordance with the links they select, and only invites individuals who navigate through the invitation page. This approach has two distinct advantages: (a) Internet users may be more likely to respond to the intercept page than to reactive recruitment methods; and (b) tracking mechanisms make it possible to determine the number of individuals exposed to the study invitation, allowing for accurate calculation of reach parameters at each step of the recruitment process. This method was employed in the present study.

The present study is part of an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT) that tests the efficacy of an Internet smoking cessation Web site (www.QuitNet.com) and proactive telephone counseling. Recruitment leverages QuitNet’s top-ranked position on major search engines to recruit Internet users seeking smoking cessation assistance. We describe the recruitment process of the first 764 participants in this study to demonstrate the feasibility of Internet recruitment and to highlight methodological issues.

Method

Recruitment

Internet users from the United States were recruited based on use of the terms quit(ting) smoking or stop(ping) smoking in a major search engine query (AOL, MSN, Yahoo, Google) and no known prior visit to QuitNet (no cookie detected). When a user clicked on a link to QuitNet in the results of a search engine query, an intercept page appeared inviting them to participate in a study to test how well Internet and telephone treatment helped people to quit. If they accepted, they were asked 10 questions (age, smoking rate, age of first puff, time to first cigarette after waking, number of quit attempts in past year, gender, race, education, zip code, and prior use of QuitNet). Three questions determined preliminary eligibility (aged ≥18, ≥5 cigarettes/day, no prior QuitNet use); remaining questions were used to characterize the largest possible denominator of potential study participants.

The recruitment software allowed investigators to control the rate of enrollment to manage research staff workload relative to fluctuations in recruitment volume and to ensure attainment of race and gender recruitment goals. When volume was high, a proportion (e.g., 1 of every 3) of eligible users was recruited. Those not recruited, as well as ineligible participants, were directed to the QuitNet home page.

If eligible, participants were asked to provide online informed consent, their name, and telephone number. Within 48 hr, a research assistant confirmed eligibility and consent, administered a baseline telephone assessment, and randomized the participant to study condition. All available recruitment process information was logged in real-time to a relational database (Microsoft SQL Server 2000; Microsoft 2000).

Results

Recruitment

Consistent with the CONSORT guidelines (Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001), Figure 1 shows the denominator at each step of recruitment. During the first 7 months of the study, 28,297 individuals were invited: 47.1% were referred from Google, 32.8% through Yahoo!, 17.6% through MSN (17.6%), and 2.6% through AOL. The most common search term was quit smoking (50.6%), followed by stop smoking (20.9%), and quitting smoking (16%). Adjusted for local time, the majority (60.3%) of individuals were recruited during work hours (9 A.M. to 5 P.M.).

Figure 1.

Preliminary recruitment data (March 8, 2005 to October 24, 2005).

Of the 28,297 invited to participate, 39.4% (11,147) accepted, 32.2% declined, and 28.4% abandoned (closed their browser). Of the 11,147 who accepted, 10,692 (96%) proceeded to the eligibility screening page and 455 (4%) abandoned. Of those who reached the eligibility screening page, 52.0% (5,557) were eligible, 4.2% (444) were ineligible, and 43.9% abandoned. Individuals were determined ineligible for one or more of the following reasons: Under age 18 (347); prior use of QuitNet (262); and smoking <5 cigarettes per day (252), with 20 of those already quit. Although 5,557 individuals were eligible, 1,943 were told the study was not currently recruiting and were redirected to QuitNet. Thus, 3,614 individuals were asked to provide online informed consent; 41.2% (1,489) consented and 58.8% (2,125) abandoned.

Of the 1,489 people who provided online consent, 51.3% (764) were confirmed eligible, completed the baseline assessment, and were randomized to treatment; 27.5% were unreachable; 4.5% were no longer interested in participating; 14.0% (208) were ineligible; and 2.8% were scheduled for the baseline phone assessment, although they were not yet enrolled at the time of this report. Of the 208 ineligible, 181 (87%) had already quit smoking.

Calculating reach estimates

Reach estimates vary depending on the denominator selected: 2.7% of all Internet users seeking cessation information (28,297); 6.9% of those who demonstrated preliminary interest in the study (11,147); 13.7% of those who were eligible to participate (5,557); 21.1% of those eligible and recruited (3,614); and 51.3% of those consented (1,489).

Randomized vs. others

Randomized participants were older, more likely to be female, and less likely to be White than those eligible and recruited (Table 1). Demographic differences were primarily related to investigator control of the recruitment process. Differences were also noted in smoking variables, such that the final sample smoked at a higher rate, was more likely to smoke within 30 min of waking, had made more quit attempts in the previous year, and began smoking at an earlier age (all p values <.01). There were no differences between subgroups on education or time of recruitment.

Table 1.

Comparison of randomized sample to denominators of interest on preliminary screening data.

| Variable | Randomized (n=764) |

All others consented (n=725) |

All others recruited (n=2,850) |

All others eligible (n=4,793) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/percent | SD | Mean/percent | SD | Mean/percent | SD | Mean/percent | SD | |

| Age | 35.12 | 10.31 | 32.59*** | 10.18 | 33.59*** | 10.53 | 33.98** | 10.54 |

| Gender (% female) | 60.5 | 57.9 | 50.0*** | 57.7 | ||||

| Education (highest grade completed) | ||||||||

| Grade 1–8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | ||||

| Grade 9–11 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.3 | ||||

| Grade 12 or GED | 19.8 | 19.6 | 21.6 | 21.4 | ||||

| College 1–3 years | 48.4 | 46.1 | 44.1 | 44.7 | ||||

| College 4 years or more | 29.2 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 30.1 | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 86.4 | 85.5 | 85.2** | 91.0*** | ||||

| Black | 7.5 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 3.4 | ||||

| Asian | 3.7 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 3.7 | ||||

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.0 | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | ||||

| Time of recruitment | ||||||||

| Early morning (6 A.M.–9 a.m.) | 11.4% | 9.0% | 9.5% | 9.5% | ||||

| Work hours (9 a.m.–5 p.m.) | 60.2% | 58.9% | 59.6% | 58.9% | ||||

| Early evening (5 p.m.–9 p.m.) | 16.4% | 17.9% | 18.8% | 18.8% | ||||

| Overnight (9 p.m.–6 a.m.) | 12.0% | 14.2% | 12.0% | 12.8% | ||||

| Daily smoking rate | 21.10 | 10.09 | 20.30 | 9.86 | 19.76*** | 9.56 | 20.00** | 9.48 |

| Time to first cigarette | ||||||||

| Within 5 min | 38.1 | 37.5 | 35.1*** | 35.3** | ||||

| 6–30 min | 39.8 | 36.0 | 36.8 | 36.8 | ||||

| 31–60 min | 14.8 | 15.6 | 15.9 | 16.5 | ||||

| After 60 min | 7.3 | 10.9 | 12.1 | 11.4 | ||||

| No. quit attempts past year | 2.88 | 5.94 | 2.16** | 4.69 | 2.42 | 6.18 | 2.39* | 5.97 |

| Age at first puff | 14.48 | 3.51 | 14.80 | 3.57 | 14.96*** | 3.71 | 14.87** | 3.69 |

Note. Comparison group for all t-test and chi-squared analyses is randomized (n=764). All others consented=1,489 minus 764=725. All others recruited=3,614 minus 764=2,850. All others eligible=5,557 minus 764=4,793.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Randomized sample

The majority of study participants were female (60.5%), White (86.4%), and college educated (48.4%). The mean age was 35.6 years (SD=10.25). Most participants (88.2%) were planning to quit in the next 30 days (Preparation). On average, participants smoked 20.29 cigarettes per day (SD=9.91), had their first puff at age 14 (SD=3.55), and became daily smokers at age 17 (SD=3.4). Participants made an average of 2.86 quit attempts in the past year (SD=4.83) and reported higher levels of desire to quit (M=9.02, SD=1.43) than confidence (M=6.16, SD=2.25). Average score on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) was 5.04 (SD=2.36), with 44% of participants scoring 6 or above, indicating a high level of nicotine dependence (Fagerström, Kunze, Schoberberger, et al., 1996). Participants were generally Internet savvy, with 74.6% having used the Internet for at least 5 years, 74.3% using the Internet several times a day, and 83.2% with broadband (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants randomized to treatment.

| Variable | Randomized (N=764) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean/percent | SD | |

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age (mean) | 35.6 | 10.25 |

| 18–29 | 33.1 | |

| 30–49 | 55.9 | |

| 50–64 | 10.6 | |

| 65 and older | 0.4 | |

| Gender (percent female) | 60.5 | |

| Education (highest grade completed) | ||

| Grade 1–8 | 0.3 | |

| Grade 9–11 | 2.4 | |

| Grade 12 or GED | 19.8 | |

| College 1–3 years | 48.4 | |

| College 4 years or more | 29.2 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 86.4 | |

| Black | 7.5 | |

| Asian | 3.7 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.5 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2.0 | |

| Income | ||

| <US$10,000 | 3.4 | |

| US$10,000–US$20,000 | 8.7 | |

| US$20,000–$30,000 | 16.4 | |

| US$30,000–$40,000 | 17.5 | |

| US$40,000–$50,000 | 13.9 | |

| US$50,000–US$75,000 | 19.4 | |

| US$75,000–$100,000 | 10.3 | |

| >US$100,000 | 10.4 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 41.5 | |

| Cohabitating | 16.0 | |

| Single | 19.0 | |

| Separated | 3.5 | |

| Divorced | 18.7 | |

| Widowed | 1.3 | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 71.3 | |

| Part-time | 9.8 | |

| Unemployed | 4.6 | |

| Homemaker | 5.9 | |

| Retired | 2.1 | |

| Student | 6.3 | |

| Smoking variables | ||

| Age at first puff | 14.08 | 3.55 |

| Age onset of daily smoking | 16.95 | 3.44 |

| Daily smoking rate | 20.29 | 9.91 |

| No. quit attempts past year | 2.86 | 4.83 |

| Baseline stage of change | ||

| Precontemplation | 0.1 | |

| Contemplation | 11.6 | |

| Preparation | 88.2 | |

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence | 5.04 | 2.36 |

| Desire to quit | 9.02 | 1.43 |

| Confidence in quitting | 6.16 | 2.25 |

| Internet use variables | ||

| Duration of Internet use | ||

| Less than 1 year | 2.5 | |

| 1–2 years | 2.1 | |

| 2–5 years | 20.8 | |

| More than 5 years | 74.6 | |

| Frequency of Internet use | ||

| Several times a day | 74.3 | |

| About once a day | 17.0 | |

| 3–5 days per week | 5.9 | |

| 1–2 days per week | 2.1 | |

| Every few weeks or less often | 0.7 | |

| Type of Internet connection | ||

| Dial-up connection | 16.8 | |

| Broadband connection | 83.2 | |

| Health status variables | ||

| Perceived health status | ||

| Excellent | 8.1 | |

| Very good | 37.5 | |

| Good | 36.2 | |

| Fair | 14.4 | |

| Poor | 3.8 | |

| Ever had smoking related illness (percent yes) | 59.1 | |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight | 2.0 | |

| Normal weight | 39.3 | |

| Overweight | 32.0 | |

| Obese | 26.7 | |

| Psychosocial variables | ||

| Any alcohol use (percent yes) | 70.4 | |

| Used more than meant to past year (percent yes) | 61.8 | |

| Wanted or needed to cut down (percent yes) | 27.2 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 6.25 | 3.25 |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale | 9.38 | 5.79 |

Discussion

Preliminary results from this ongoing study demonstrate the feasibility of using an active user-intercept protocol to recruit smokers into a research trial. Linking a study recruitment protocol to highly utilized search engines through active user sampling results in very high initial reach (28,297) to a large sample of smokers looking for cessation assistance. There are significant portions of this initial pool of participants that drop out of the recruitment flow prior to enrollment. Using the broadest population denominator, preliminary results suggest that approximately 2.7% of Internet users looking for online cessation information will enroll in a research trial such as this one. However, this denominator may be overly conservative and not appropriate to estimate reach: It is analogous to counting all newspaper subscribers who read an advertisement for a cessation trial, many of whom will not even call the research center. Other potential denominators to estimate the reach of this recruitment approach to the population of interest are those who indicated some preliminary interest (11,147) and/or those who were eligible (5,557) and recruited (3,614). Reach estimates using these denominators were 6.9%, 13.7%, and 21.1%, respectively. Given that more than 8 million smokers use the Internet to find cessation information each year (Fox, 2005), active user sampling could potentially reach thousands of smokers with the opportunity to participate in a research trial.

The final sample differs from eligible participants on daily smoking rate, time to first cigarette, number of previous quit attempts, and age of first puff, suggesting a sample of heavier, more dependent smokers who may be more motivated to quit smoking. Education level did not appear to influence enrollment. Differences in race and gender were also observed, but may be attributed to investigator control of recruitment. Including a small number of additional questions in online eligibility screening allows for such comparisons and seems to be well accepted by participants. As in other studies of Internet cessation (Etter & Perneger, 2001; Feil et al., 2003; Koo & Skinner, 2005; Stoddard et al., 2005), the majority of our sample is comprised of younger, female, college-educated individuals with substantial Internet experience. The ability to adjust recruitment volume (oversampling or undersampling) based on race and gender has been critical to meeting goals for under-represented minority populations. To date, we have used this feature primarily to control enrollment of White females who comprised 62% of the participants enrolled in the first 3 months. Minority recruitment has proceeded more slowly, with Blacks enrolling at the highest rate among minority groups. Although online recruitment can be used to conduct preliminary eligibility screening and consent, eligibility and consent should be reconfirmed prior to randomization.

As reported in Cobb, Graham, Bock, Papandonatos, and Abrams (2005a), many individuals turn to the Internet for support within days of their quit. In the present study, individuals were excluded who had not smoked at all in the prior 24 hr. This stringent eligibility criterion was selected since this is one of the first large-scale randomized controlled trials of Internet smoking cessation. As a result, approximately 24% (181 of 764) of potential participants were determined to be ineligible. Since the majority of quit attempts in the United States are unassisted (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002), and since the Internet is a readily available resources for recent quitters, future studies should examine the efficacy of Internet-based cessation programs in preventing relapse.

The Internet raises unique reporting, methodological, and analysis issues. Traditional Web server log files may provide insufficient data to determine actual numbers of individuals reached. To understand barriers to studying enrollment encountered by smokers, and to determine the generalizability of the final sample, Internet smoking cessation trials should obtain and retain information about those not enrolled. This preliminary study must be interpreted cautiously and awaits independent replication. As with most other clinical trials, only a small portion of potential participants enrolled in this study. However, results suggest that Internet-based research using active user-intercept recruitment is feasible. Creative strategies can be used to sample participants, estimate a variety of parameters of reach (denominators), and measure aspects of potential selection bias that are implicit in all traditional clinical trials but often cannot readily be estimated (e.g., those who read a newspaper advertisement for a study but never respond).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (5R01CA104836-02). We acknowledge and thank Lan Jiang, M.S., Crystal Davis, MPH, and Pearl Zakroysky, B.A. for their assistance on this project.

Contributor Information

Amanda L. Graham, Brown Medical School, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Providence, Rhode Island

Beth C. Bock, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, Brown Medical School/The Miriam Hospital, Providence

Nathan K. Cobb, Massachusetts General Hospital, Pulmonary and Critical Care Unit, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Raymond Niaura, Brown Medical School/Butler Hospital, Providence, RI, USA

David B. Abrams, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

References

- Abrams DB, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer W. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: A combined stepped-care and matching model. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18:290–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02895291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Graham AL, Bock B, Papandonatos G, Abrams DB. Initial evaluation of a ‘real-world’ Internet smoking cessation system. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005a;7:207–216. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Graham AL, Stoddard J, Rabius V. Evaluation of Internet based cessation programs—Part I. Proceedings of the National Conference on Tobacco or Health; Chicago, IL. 2005b. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Brock E. RE-AIM: Evidence-based standards and a Web resource to improve translation of research into practice. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:75–80. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Perneger TV. A comparison of cigarette smokers recruited through the Internet or by mail. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:521–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO, Kunze M, Schoberberger R, Breslau N, Hughes JR, Hurt RD, Puska P, Ramstrom L, Zatonski W. Nicotine dependence versus smoking pervalence: comparison among countries and categories of smokers. Tobacco Control. 1996;5(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil EG, Noell J, Lichtenstein E, Boles SM, McKay HG. Evaluation of an Internet-based smoking cessation program: Lessons learned from a pilot study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:189–194. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000073694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. Health Information Online. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addictions. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmirek L, Neubarth W. Improving Web based Intercept surveys: A framework for the active user sampling. Proceedings of The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) 60th Annual Conference; West Palm Beach, FL. 2005. Apr 28, Retrieved from: http://www.websm.org/main/baza/baza.php?bid=3361&avtor=619. [Google Scholar]

- Koo M, Skinner H. Challenges of Internet recruitment: A case study with disappointing results. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7:e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenert L, Skoczen S. The Internet as a research tool: Worth the price of admission? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:251–256. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2404_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG for the CONSORT Group. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard JL, Delucchi KL, Muñoz RF, Collins NM, Pérez Stable EJ, Augustson E, Lenert LL. Smoking cessation research via the Internet: A feasibility study. Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10:27–41. doi: 10.1080/10810730590904562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Randomized controlled trial of a Web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program as a supplement to nicotine patch therapy. Addiction. 2005;100:682–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]