Abstract

Misperceiving a woman’s platonic interest as sexual interest has been implicated in a sexual bargaining process that leads to sexual coercion. This paper provides a comprehensive review of sexual misperception, including gender differences in perception of women’s sexual intent, the relationship between sexual coercion and misperception, and situational factors that increase the risk that sexual misperception will occur. Compared to women, men consistently perceive a greater degree of sexual intent in women’s behavior. However, there is evidence to suggest that this gender effect may be driven largely by a sub-group of men who are particularly prone to perceive sexual intent in women’s behavior, such as sexually coercive men and men who endorse sex-role stereotypes. Situational factors, such as alcohol use by the man or woman, provocative clothing, and dating behaviors (e.g., initiating the date or making eye contact), are all associated with increased estimates of women’s sexual interest. We also critique the current measurement strategies and introduce a model of perception that more closely maps on to important theoretical questions in this area. A clearer understanding of sexual perception errors and the etiology of these errors may serve to guide sexual-assault prevention programs toward more effective strategies.

1. Introduction

Sexual bargaining is a complicated, dynamic social process by which potential partners communicate interest or lack of interest in pursuing a sexual relationship with each other. Given that the sources of communication bridge non-verbal and verbal domains (Fichten, Tagalakis, Judd, Wright, & Amsel, 2001) and often are veiled so as to allow exploration of mutual interest versus non-reciprocity (Henningsen, 2004), it should come as no surprise that the process is vulnerable to errors in social decoding and can be confusing for both actors (Abbey, 1982). Misinterpreting a partner’s sexual intent may lead to a failure to detect and pursue a potentially interested partner, or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, a failure to discontinue pursuit of a partner who has attempted to signal that he or she is not interested in a sexual relationship. Given individual differences in the directness of sexual communication (Byers, Giles, & Price, 1987), it is predictable that errors in sexual-intent decoding occur frequently in populations such as college students, many of whom are actively dating and seeking partners (Abbey, 1987). When misperception of a partner’s sexual communication does occur, the negative outcome generally does not exceed social embarrassment and simply highlights the need to communicate more explicitly (Byers & Lewis, 1988). However, among a sub-group of individuals, sexual misperception may be part of a constellation of individual and situational variables that increase the probability of more socially problematic behavior such as sexual coercion.

One complication in understanding sexual coercion is that very different trajectories may lead to the same negative outcome, sexual violence. The current review constrains the question to sexually coercive behavior, between known partners, that is not premeditated, but likely purposeful in the moment. As recommended by Adams-Curtis and Forbes (2004), sexual coercion is defined here as “any situation in which one party uses verbal or physical means (including administering drugs or alcohol to the other party either with or without her consent) to obtain sexual activity against freely given consent” (p. 99). Note that the definition includes legally defined rape, but also more broadly includes coercion without physical force and sexual activity without penetration. We will focus on male perpetrators, not because women are excluded from the category, but rather because sexually coercive incidents, committed by men against women, are more common (Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987).

Heterosexual misperception can be construed broadly as decoding errors in any element of a sexual bargaining process, from early interest to interpretation of consent. While there has been significant interest in the decoding of consent cues as a potential source of error leading to sexual coercion (Byers, 1988; Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999), the current review is not concerned primarily with men’s perception of women’s sexual consent versus non-consent. Instead, the review focuses on men’s ability to distinguish sexual interest from platonic interest (friendliness), which is a decoding process that likely occurs relatively early in an interaction and may set the stage for later sexual interactions. In order to map the current state of this inquiry, we review gender differences in perception of sexual intent, individual differences related to sexual coercion risk and situational factors influencing sexual misperception.

2. Gender differences in perception of women’s sexual intent

Very early in the study of sexual aggression, investigators speculated that men’s sexually coercive behavior might be linked peripherally to errors in decoding women’s sexual interest (Russell, 1975). Based on interviews with sexually aggressive men, it was suggested that they are hyper-sensitive to cues of sexual interest, including those that were not intended to be perceived as interest (Kanin, 1969). This misperception of the degree to which a woman is interested in pursuing a sexual encounter was thought to lead the man to be frustrated and confused when the woman later unexpectedly turns down his sexual overtures, and, in turn, to motivate the man to react with aggression (Kanin). However, little empirical work was conducted on this hypothesis until Abbey (1982) began to investigate gender differences in the perception of sexual intent. Beginning this review by focusing on gender differences allows us to place perceptual deficits displayed by sexually coercive men in a normative context. By providing a baseline of representative sexual decoding, we will be in a better position to identify those attributes or deficits unique to sexually coercive men. This, in turn, speeds the discovery of the underlying mechanisms and etiology of sexually coercive behavior.

After a personal experience in which a genuine attempt to be friendly was misperceived as a sexual invitation, Abbey (1982) became interested in whether such errors could be related to gender differences in perception of what “counts” as sexual interest rather than platonic friendliness. Perhaps the verbal and non-verbal behaviors that women consider friendliness are categorized quite differently by men. To test this possibility, Abbey measured gender differences in reported perception of sexual intent in a laboratory setting. Two male–female dyads participated in each session. Members of a conversing dyad were instructed to discuss their experiences at college for 5 min, while members of an observing dyad surreptitiously viewed the interaction. All participants rated the degree to which each member of the conversing dyad behaved in a flirtatious, seductive, and promiscuous way. Although men and women viewed the same social interaction, gender differences in the evaluation of the event emerged. Men, whether they were observing or participating in the conversation, were more likely than women to perceive the women in the conversing dyad as more sexually interested in their partners, and rated them higher on the sexuality-related adjectives. Men’s increased perception of sexuality in the situation generalized to their ratings of other men. They also rated the male conversationalists higher on sexuality-related adjectives than women rated them.

The possibility that men and women indeed may have different conceptualizations of women’s sexually interested and friendly behavior sparked a long string of replications and extensions of the research. Abbey and her colleagues consistently found that men, when compared with women, rated female targets as conveying more sexual intent. This was true whether the female targets were depicted in still photographs (Abbey, Cozzarelli, McLaughlin, & Harnish, 1987; Abbey & Melby, 1986), in written vignettes (Abbey & Harnish, 1995), or in a live interaction (Abbey, 1982; Abbey, Zawacki, & McAuslan, 2000). This result may be due to a general tendency for men to perceive the world in sexualized terms, as they also rated male targets as behaving more sexually than the women observers perceived male targets (Abbey; Abbey & Melby; Abbey & Harnish; Abbey, Zawacki, & McAuslan). This systematic perception of sexuality in all targets should be acknowledged, even as we shift focus to consider a subset of this effect, that is men’s perception of women, as it is likely more directly relevant to understanding male-initiated aggression against women.

Outside of the originating laboratory, researchers have continued to find gender differences in perceptions of women’s behavior. Edmonson and Conger (1995) replicated the effect using the same methodology used in the Abbey (1982) paper, as well as in impoverished rating conditions such as audiotapes or photographs of men and women interacting. Similar replications involving live interactions in the laboratory also have provided consistent evidence that men perceive more sexual intent in women’s behavior than women perceive in their own behavior or the behavior of other women (Saal, Johnson, & Weber, 1989; Shea, 1993). In addition, when participants rated written descriptions of behaviors that might occur during a dating encounter (e.g., “the woman touches the man’s arm”), men tended to perceive the female behaviors as indicating more sexual intent than women reported the behaviors indicating when they use them (Haselton & Buss, 2000; Willan & Pollard, 2003).

The effect first demonstrated within the laboratory extends outside of the laboratory. Sixty-seven percent of college women indicated that they have had at least one experience in which an attempt to be friendly was misperceived as a sexual come-on, and 38% indicated that they have had such an experience within the past month (Abbey, 1987; see also Haselton, 2003).

It is important to note that some of these investigations confounded the effect of gender with the effect of self versus other ratings. When a man’s ratings of a woman’s behavior are compared to the woman’s ratings of her own behavior, the comparison includes two variables. The raters differ not only by gender, but also by whether they are judging themselves or someone else. That is, if a man perceives more sexual intent in a woman’s behavior than she perceives in herself, the effect may be due to gender (men see more sexuality in events than women), or it may be due to a decreased tendency to label oneself as sexually provocative (an individual rating herself may be inclined to attribute warmth to situational task demands while a rater judging someone else may explain behavior by appealing to internal attributions such as sexual interest; Jones & Nisbett, 1971). Some investigators tentatively have accepted the “premise that individuals have the best access to their own thoughts and feelings” (Edmonson & Conger, 1995, p. 180), or have stated that men’s accuracy can be assessed directly by comparing a woman’s self-reported sexual intentions to “the man’s perceptions to determine if he correctly estimated her level of sexual interest” (Abbey et al., 2005; p. 150). However, it also can be suggested that women’s self-reports are clouded by biases and self-protection that may complicate the assessment of gender effects (Haselton & Buss, 2000).

To separate the layer of self-other distinctions from the primary gender effect, most investigators have used methodologies that require male and female participants to rate external interactions rather than an interaction in which they are a participant. In one study, participants rating a male–female couple depicted in a photograph did not perceive female sexual interest differently as a function of observer gender (Cahoon & Edmonds, 1989). However, when evaluating short descriptions of dating behaviors, men tended to perceive female behavior as indicating sexual intent to a greater extent than women rated the same female behavior, but only when the dating behaviors were relatively inexplicit (Fisher & Walters, 2003; Kowalski, 1993). For example, men perceived more sexual intent in women’s behavior than women perceived when “a woman meets a man for coffee.” However, when the behavior was more intimate, such as agreeing to go home with a man, men and women perceived an equal degree of sexual intent in the woman’s behavior (Fisher & Walters, 2003). Most investigators have reported that men perceive a greater degree of sexual intent in the behavior of a female character in written or videotaped dating vignettes than women perceive in the character’s behavior (Botswick & Delucia, 1992; DeSouza, Pierce, Zanelli, & Hutz, 1992; Lenton & Bryan, 2005; Koukounas & Letch, 2001; Muehlenhard, 1988; Regan, 1997; Shotland & Craig, 1988; Vrij & Kirby, 2002). Interestingly, men continue to perceive more sexual intent than do women when judging the female characters’ behavior, even outside of dating interactions, when there are clear cues that the conversation is professional in nature. For example, compared to women, men perceive more sexual intent in depictions of a female student asking a male professor for a paper extension, a female professor responding to a male student’s request for a paper extension, and a training videotape of a male manager training a new female cashier (Johnson, Stockdale, & Saal, 1991; Saal et al., 1989). It should be noted that results have been mixed, with some investigators reporting that men and women perceived similar levels of sexual intent in female characters (Quackenbush), and others reporting mixed results (Sigal, Gibbs, Adams, & Derfler, 1988), or only a trend in the correct direction (Leigh, Aramburu, & Norris, 1992).

Of the 25 papers cited to support the claim that men perceive more sexual interest than women perceive in women’s displays, only 11 reported an estimated effect size or provided the descriptive statistics necessary to calculate an effect size. Among these 11, the effect size of the gender difference ranged from small (d=0.11) to large (d=1.13; Cohen, 1977). Across the investigations, the mean effect size was moderate (d=0.63), suggesting that this gender difference is relatively robust and should be visible in sample sizes as small as 90 (split equally between genders). Note that among the three investigations failing to replicate the effect, the sample size for one study was below this threshold (Quackenbush, 1987). The remaining failures appear to have had adequate sample sizes (Cahoon & Edmonds, 1989; Sigal et al., 1988-study one). To understand the variation in effect sizes across studies, it may be of interest to consider plausible moderators in a more formal meta-analysis after a sufficient number of studies have been conducted.

3. Measurement issues

The measurement strategies common in investigations of gender differences in perception of sexual intent are often directly translated into investigations of sexual coercion. For this reason, we can anticipate that any methodological problems inherent in gender difference investigations of sexual perception may also be present in the sexual coercion literature. Thus, by providing a critical review of study design, we may foresee the challenges facing sexual coercion investigators. Two primary methodological problems confuse the theoretical interpretation of gender differences in sexual perception. First, the difficulty in accessing a gold standard for correct perception confuses interpretation of observed differences in perception, and second, the source or etiology of observed differences has rarely been investigated. A Signal Detection Theory (SDT; Green & Swets, 1966) approach can be used to address these problems, both in the gender difference literature as well as within later applications to the subset of sexually coercive men.

When discussing differences in degree between men’s and women’s perceptions of a female target’s sexual interest, it is difficult to measure the target’s “true” degree of sexual interest. Gender differences in the perception of women’s sexual intent may be due to men over-perceiving sexual interest, or alternatively, to women under-perceiving sexual interest. The most common assumption is that men are prone to perceive sexual intent where it does not actually exist, perhaps due to over-sexualized social norms or social learning (Abbey, 1982), to script-based interpretations of dating situations (Geiger, Fischer, & Eshet, 2004; Lenton & Bryan, 2005), to evolutionary pressure to be biased to perceive sexual intent wherever it may exist in order to maximize mating opportunities (Haselton & Buss, 2000) or to learning situations in which misperception is reinforced. The available literature has been cited as a demonstration that “men do indeed over estimate women’s sexual interest” (Haselton & Nettle, 2006, p. 57; italics added). This type of explanation presumes that women’s perception of the sexual intent of other women is the gold standard by which to measure interest, and therefore, that over-perception by men relative to women actually indicates misperception by men. However, as Shotland and Craig (1988) noted, “the effectiveness of any communication depends both on what is sent and on what is received…. It is difficult to say whether men or women are more correct because there is no objectively correct criterion on which a direct test of this question can be based” (p. 71). Clearly, there is no reason to exclude prematurely the possibility that women are prone to under-perceive sexual intent in other women. Heterosexual women certainly would have less experience in recognizing and less motivation to recognize the subtle cues another woman may use to signal availability, and hence, may be more likely to miss signals of interest that heterosexual men are tuned precisely to perceive.

Quite apart from questions about the appropriate gold standard, and perhaps more important, is the inability of current measurement strategies to distinguish between multiple theoretical models that may account for participant task performance. Two distinct theoretical explanations for observed individual differences have been espoused (Treat, McFall, Viken, & Kruschke, 2001). A sensitivity explanation for gender differences argues that men are not able to distinguish among subtle affective cues. A bias explanation argues that compared to women, men require fewer impelling cues prior to labeling a behavior sexual interest, that is, their threshold for labeling a woman as sexually interested is lower. Abbey’s (1982) summary of the available literature concluded that men are insensitive to women’s cues. This insensitivity explanation of observed gender differences assumes that women can accurately discriminate among other women’s affective states, whereas men have considerable difficulty discriminating. This explanation predicts that in some instances, men will mistake friendliness for sexual interest, and in other instances, they will mistake sexual interest for friendliness. Others, such as Koukounas and Letch (2001), argue that both men and women are equally capable of discriminating the same cues, but men are biased to perceive sexual interest, that is, they have a lower decisional threshold for labeling a behavior as sexual interest. Despite the distinction in the process theoretically assumed to lead to gender differences, both camps have generally used men’s and women’s average ratings of sexual interest as support. Unfortunately, the comparison of mean differences between men and women’s ratings of an interaction, or the accuracy of an observer’s decoding compared to the actor’s self-report, cannot identify the source of the discrepancy. By relying on mean difference comparisons, we are unable to distinguish between an insensitivity explanation and a bias explanation of gender differences (see McFall & Treat, 1999).

Fortunately, a system of parsing sensitivity differences from decisional processes or bias, which exists independently of presumptions of gold standards and relies instead on relative differences, has been long available in cognitive psychology. Treat et al. (2001) have argued that the system provides a measurement model that matches the theoretical needs of the field (also Lipton, McDonel, & McFall, 1987; McFall, 1990; McFall & Treat, 1999). Drawing on a long history of cognitive science approaches to simple perception, they argue that differences in perception of sexual intent can be viewed from two perspectives, both conducive to understanding and investigating within a Signal Detection Theory (SDT) framework (Green & Swets, 1966).1 First, these differences may be attributed to men’s relative insensitivity to women’s sexual intent cues. That is, compared to women, men may find the task of discriminating cues indicative of sexual interest from cues indicative of platonic interest to be a genuinely more difficult task than women find it to be, and thus, are likely to make more identification errors in both directions. Although not necessarily couched in the same terms, some researchers have suggested that the above gender effect may be due to insensitivity on the part of male observers. For example, Abbey (1982) has noted that the available literature suggests that “males are unable to distinguish females’ friendly behavior from their seductive behavior” and that “it is difficult to distinguish friendly cues from sexual cues. Many verbal and non-verbal behaviors such as smiling, agreeing with someone, making eye contact, and touching are used to convey both platonic friendliness and sexual attraction” (Abbey & Harnish, 1995, p. 298). Relative sensitivity differences between men and women map on to ideas of errors due to an inability to discriminate between categories of behavior.

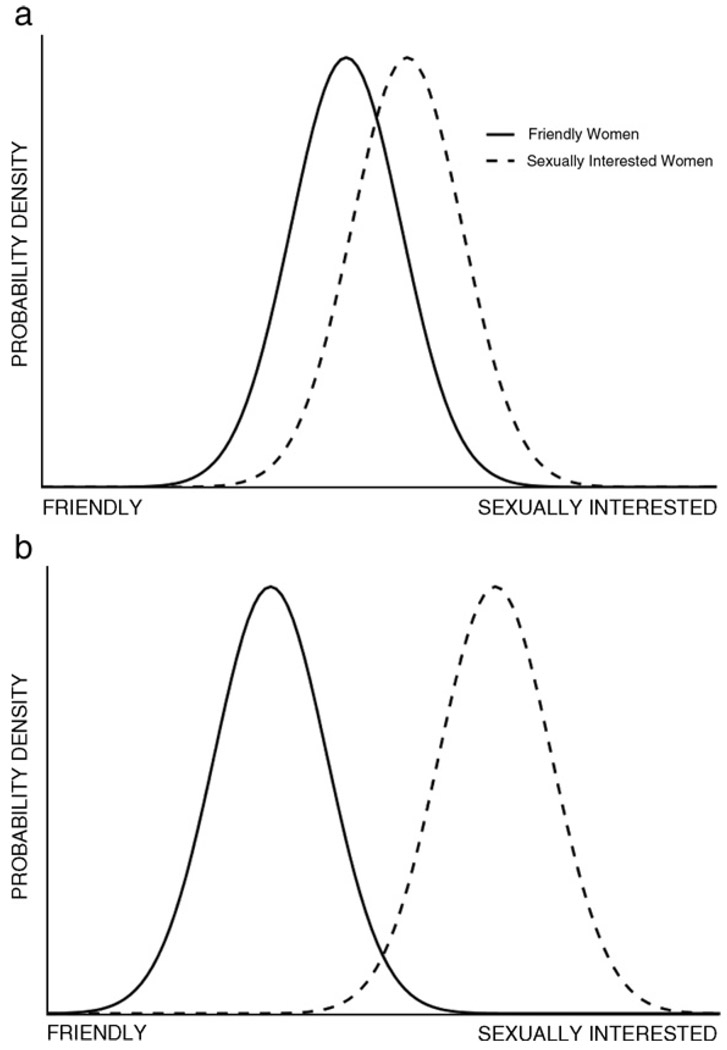

Fig. 1 illustrates an SDT explanation for the perceptual process that leads to error due to insensitivity. Imagine that men perceive women’s positive affective cues along a continuum ranging from pure platonic interest to obvious sexual interest. Cues that are perceived at the ends of the continuum are seen clearly as friendliness or sexual interest, while cues perceived near the midpoint of the continuum are perceived to be more ambiguous. The distribution on the right side of the figure represents perception of all women’s sexual interest, with the average strength of signaling or the mean of the distribution shifted toward sexual interest. The distribution on the left side represents perception of all women’s platonic interest or friendliness, with the mean of the distribution shifted toward friendliness. Notice that the two distributions overlap. Some women on the extreme right tail of the friendliness distribution emit platonic interest cues that are perceived as sexual interest. Similarly, some women in the extreme left tail of the sexual interest distribution exhibit sexual interest cues that are perceived as friendliness. An individual’s sensitivity to the distinction between friendliness and sexual interest is represented by how close the means of the two perceptual distributions are to one other. Distributions such as those in Fig. 1a are quite close, with significant overlap, and thus, there is considerable confusion between the categories. In contrast, the distributions in Fig. 1b are quite far apart, with limited overlap, so that most points along the continuum clearly fall into one or the other distribution. An individual whose perceptual distributions of friendliness and sexual interest are characterized by Fig. 1a will be less sensitive to the distinction between the two categories than an individual whose perceptual distributions are characterized by Fig. 1b. A sensitivity explanation for gender differences in sexual perception essentially argues that Fig. 1a represents men’s perception of the distinction between friendliness and sexual interest, and Fig. 1b represents women’s perception.

Fig. 1.

Normal probability distributions representing perception of friendliness and sexual interest. Panel a depicts the perceptual distributions of an individual who is relatively insensitive to the difference between friendliness and sexual interest. Panel b depicts the perceptual distributions of a more sensitive individual.

Relative insensitivity to differences between friendliness and sexual interest cues on the part of men, as compared to women, is not always embraced as a probable explanation. After demonstrating that men rate video clips designed to indicate sexual interest higher in sexual interest than men rate video clips designed to indicate friendliness, Shotland and Craig (1988) conclude that “males could distinguish between sexually interested and friendly behavior. Therefore it is not logical to infer that the gender differences result from males’ inability to decode female cues adequately” (p. 71). While this result certainly supports the claim that men are not categorically insensitive to differences in women’s behavioral cues, it in no way rules out the possibility that men may be less sensitive than women to sexual interest cues. If examples of friendliness and sexual interest are sampled from the extremes of the continuum, then the cues will be particularly discriminable and null findings may be attributable to a ceiling effect. If examples of friendliness and sexual interest are sampled from a uniform distribution, then measurement of perceptual sensitivity on a continuous scale is possible. As previously noted, gender differences are particularly notable when cues are perceived to be ambiguous (Fisher & Walters, 2003; Kowalski, 1993), rather than distinct, as is the case here. Thus, differences in relative sensitivity to affect cues continue to be a viable explanation for gender differences in the perception of sexual intent.

Alternatively, gender differences may be due to differences in the thresholds for labeling sexual interest; in Signal Detection terms, this would be a decision criterion or bias difference (Green & Swets, 1966; Haselton & Buss, 2000; McFall & Treat, 1999; Treat et al., 2001). Men and women may process and encode the same behavioral cues, but men may require less evidence of sexual interest before being willing to label the behavior as indicating sexual interest, whereas women may require more evidence before making the same decision. This difference in decisional processes also has been used to describe the gender differences in perception of sexual intent (Bondurant & Donat, 1999; Saal, et al., 1989; Shotland & Craig, 1988). For example, Koukounas and Letch (2001) argue that “it is possible that men have lower perception thresholds for sexual-information processing — that is, they may require less sociosexual information than women before they label a situation as sexual” (p. 452).

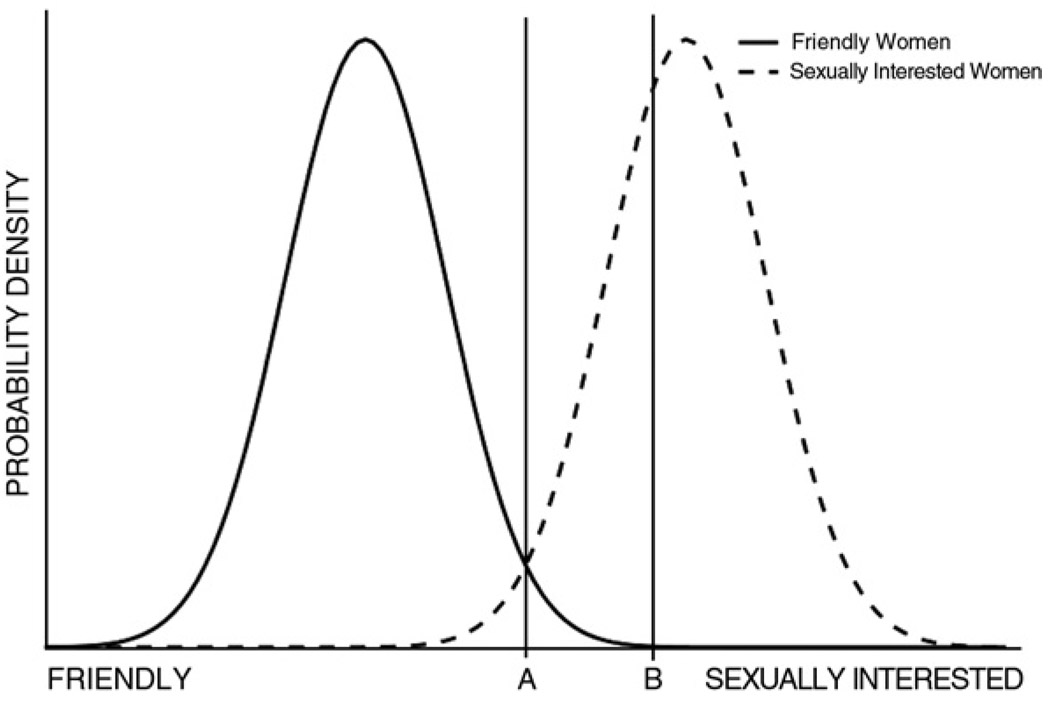

Fig. 2 illustrates an SDT explanation of gender differences due to bias. Assume that men and women’s sensitivity is identical. For example, both men and women might perceive the friendliness and sexual interest categories as overlapping slightly. Their ratings of women’s sexual interest still may differ if their decisional criteria for labeling sexual interest vary. An individual with the task of deciding whether a woman is displaying sexual interest will switch from labeling behavior friendliness to labeling behavior as sexual interest at some point on the continuum. An individual who switches at point A, as labeled in Fig. 2, will perceive women displaying affect that ranges from extremely friendly up to point A on the continuum to be friendly women (i.e., they belong to the friendly distribution). Similarly, women displaying affect above point A will be perceived as sexually interested women. If the two distributions overlap, some mistakes will be inevitable; notice that the extreme tail of the friendly distribution falls above point A and those friendly women will be incorrectly categorized as sexually interested. In addition, a small portion of the extreme tail of the sexually interested distribution falls below point A and will be mistakenly labeled friendly. Now imagine that a second person switches from labeling behavior friendly to sexual interest at a different point along the continuum. This second person is much more conservative and changes his or her decision at point B, which is shifted toward the sexual interest end of the continuum. This person needs women to display more convincing sexual interest before he or she perceives the woman as belonging to the sexually interested distribution. Notice that this person’s decisional threshold lies above most of the friendly distribution (i.e., very few friendly women will be mistakenly called sexually interested). However, the shift also means that a much larger proportion of the sexual interest distribution falls below the decisional threshold. This person will make many more mistakes in which he or she calls sexually interested women friendly. Now imagine that point A is the decisional threshold of a man, and point B is the decisional threshold of a woman. The difference in decisional thresholds would result in the man reporting more sexual interest in ambiguous situations, and the woman reporting less sexual interest in ambiguous situations. If the behavior falls above the male threshold, but below the female threshold, men and women will disagree about the appropriate interpretation.

Fig. 2.

Normal probability distributions representing perception of friendliness and sexual interest. Decision criterion points are depicted to illustrate decisional bias. Point ‘A’ represents a liberal criterion; point ‘B’ represents a conservative criterion.

It should be noted that SDT is a performance model. To obtain SDT parameter estimates, it is necessary for participants to complete a task in which they classify the affect of actors across multiple trials. This creates a measure of optimal performance that is minimally vulnerable to participants’ faking or lying about good performance (McFall, 1990). In order to estimate an individual’s sensitivity and bias, the individual must view numerous visual stimuli or vignettes and indicate whether platonic or sexual interest was communicated. This allows the investigator to obtain a stable estimate of the proportion of hits (correctly identifying a sexually interested woman) and false alarms (erroneously identifying a friendly woman as sexually interested), which then can be used to calculate estimates of each individual’s sensitivity to the distinction between friendliness and sexual interest, as well as his or her decisional threshold or bias (see Macmillan & Creelman, 2004). As opposed to many arenas in clinical and social psychology which have relied heavily on self-report measures to assess the construct of interest, many investigators in sexual misperception already have required participants to provide a judgment of sexual interest in a real situation or in a photograph. To move from comparing mean ratings between men and women to establishing reliable estimates of an individual’s sensitivity and bias within the task, we need only to increase the number of trials in which participants provide a decision about sexual interest versus friendliness and then utilize analytical techniques that distinguish between error due to perceptual insensitivity and error due to differences in decisional thresholds.

While it is clear that reliable gender differences in the perception of women’s sexual interest exist, it remains unclear whether this difference is attributable to gender differences in perceptual sensitivity or to variance in decisional bias. Future research that makes use of SDT or an alternative model may be able to do a better job of delineating the source of disagreement between men and women. In addition, just as distinguishing the source of error may help to organize thinking about gender differences, it also may prove to be a useful framework from which to approach sexual perception as it relates to sexual aggression.

4. Individual differences in sexual perception

Despite consistent framing of differences in sexual perception as due to gender differences, some research suggests that the majority of men and women tend to agree on the meaning of sexual communication (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999) and that only a sub-group of men may be driving the gender effect. That is, men’s tendency to perceive more sexual intent than women may be moderated by individual differences in attitudes and behavioral history. Many of the individual differences that predict sexual misperception are closely related to sexual coercion risk. For example, men who generally reject sex-role stereotypes and perceive sexual relationships as mutual do not differ from women in their perception of sexual intent communicated via mundane dating behaviors such as eye contact (Kowalski, 1993). Only men who strongly endorse sex-role stereotypes and perceive sexual relationships as exploitive and manipulative perceive more sexual intent than women. Another study found evidence that men who endorse rape-supportive attitudes, such as victim blaming, perceived more female sexual intent (in vignettes) than women, whereas men who rejected rape-supportive attitudes did not differ significantly from women (Abbey & Harnish, 1995). Thus, the extreme group of men, not all men, may be responsible for the gender effect. Fisher and Walters (2003) defined a similar group of “macho” men who scored above the male median on measures of traditional and callous attitudes toward women. These “macho” men perceived more sexual intent in female vignette characters than men who rejected these attitudes. However, not all research evidence has been consistent with this claim, Vrij and Kirby (2002) reported that both male gender and endorsement of rape-supportive attitudes predicted perception of women’s sexual intent, but that gender differences in rape-supportive attitudes did not fully account for the gender effects. Quackenbush (1987) failed to find that gender role (sex-typed versus androgynous or undifferentiated) moderated the gender effect, but the sample sizes were so small as to make detection of all but a large effect unlikely.

Evidence that some men may be more prone to sexual misperception than others is provided by correlational studies that examined the association between men’s perception of women’s sexual intent and negative attitudes toward women. For example, acceptance of rape-supportive attitudes correlated positively with perception of sexual intent in women’s dating behaviors (Bondurant & Donat, 1999). Men’s degree of hostility toward women and their acceptance of rape-supportive attitudes accounted for 19% of the variance in perception of sexual intent (Willand & Pollard, 2003); alternatively, the combination of stronger traditional attitudes toward women, hypermasculinity and low social desirability accounted for 18% of the variance in men’s perception of women’s sexual intent (Fisher & Walters, 2003).

As noted above, performance-based evaluations of sexual perception allow the parsing of sensitivity from bias explanations for individual differences in perception of sexual intent. In one such study, it was found that decreased accuracy among men who accept rape-supportive attitudes was due in part to men’s relative insensitivity to women’s affect, which leads them to have difficulty discriminating sexual intent from other affect categories (Farris, Viken, Treat, & McFall, 2006). Decisional processes also played a role in predicting the degree to which men endorsed rape myths; however, insensitivity was more clearly and reliably linked to sexual coercion risk and history. High-risk men’s decisions about sexual interest were influenced substantially by less-relevant cues such as women’s clothing styles. Men who more strongly endorsed rape myths were more likely to be swayed by provocative clothing and assume that provocatively dressed women were also sexually interested. Similarly, a performance-based investigation relying on a separate model to understand men’s perceptual processing of women, found that men who pay relatively less attention to women’s affective cues than to their clothing exposure were also less sensitive to women’s negative, non-interest cues in a sexual vignette (Treat et al., 2001).

As noted above, many of the attitudinal correlates of perception of a greater degree of sexual intent in women’s behavior and communication are associated in turn with sexual coercion. Endorsement of rape-supportive attitudes, traditional and hostile attitudes toward women, and hypermasculinity are all more common among men with histories of perpetrating sexual coercion (Hall, Teten, DeGarmo, Sue, & Stephens, 2005; Hersh & Gray-Little, 1998; Koss & Dinero, 1988; Meuhlenhard & Linton, 1987). Thus, it is not unexpected that men who report a history of sexual coercion perceive more sexual intent in women’s behavior than men without a history of sexual violence. Compared to non-coercive men, sexually coercive college men self-report more incidents in which they mistakenly thought a woman was sexually attracted to them, only to find out later that she was only trying to be friendly (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Abbey et al., 1998; Abbey, McAuslan, Zawacki, Clinton, & Buck, 2001; Abbey et al., 2002). They are also more likely than non-coercive men to believe that a woman with whom they are interacting is behaving in a sexually expressive manner (Shea, 1993). External observers who coded the same interactions were unable to distinguish any difference in the women’s behavior. Sexually coercive men perceive more sexual intent in women’s dating behaviors (e.g., eye contact, playing romantic music) than non-coercive men, but they do not differ in the degree to which they perceive sexual intent in overtly sexual acts, such as a woman removing her blouse or touching her partner’s genitals (Bondurant & Donat, 1999). A ceiling effect may explain non-significant group differences in this case. Sexual coercion history combined with rape-supportive attitudes accounted for 25% of the variance in perception of women’s sexual intent (Bondurant & Donat). Performance-based measures of men’s ability to identify women’s dating-relevant affect revealed that sexually coercive men were relatively insensitive to women’s affect (e.g., friendliness versus sexual interest), but only when they made the decision quickly (Farris et al., 2006).

Other investigators have reported mixed results—in some situations sexually coercive men perceived women to be more seductive than non-coercive men, but in other dating situations the effect was absent or in the opposite direction (Malamuth & Brown, 1994). Others have failed to replicate the effect altogether, whether participants were rating videotaped dating clips (Koralewski & Conger, 1992) or a confederate trained to interact with participants (Abbey, Zawacki, & Buck, 2005). Koralewski and Conger concede that the failure to replicate may be due to small sample sizes, but argue that the small absolute differences between groups indicate a small effect size that has limited clinical significance. While they are correct in noting that the effect sizes associated with relevant individual differences in sexual coercion history may be small, small effects are not necessarily clinically insignificant. In multi-determined phenomenon such as sexual aggression, reliable but small effects may be crucial in understanding the convergence of situational, attitudinal, and personality factors that ultimately result in sexually coercive behavior (Bernat, Calhoun, & Stolp, 1998).

In sum, individual differences in attitudes and beliefs that have been associated with sexual coercion, as well as a direct history of perpetrating sexual coercion, are associated with an increased tendency to perceive sexual intent in women’s behaviors. A performance-based analysis of high-risk men’s social perception suggests that these differences may be due to an insensitivity to the distinction between sexual interest and other affect categories (Farris et al., 2006). If replicated, this preview into the process that leads to inaccuracy may have important intervention implications. It suggests that it may be important to provide training to high-risk men to increase the discriminability of categories such as platonic and sexual interest. Other work has suggested that high-risk men’s decisions may be particularly prone to interference from salient but less-relevant dimensions, such as physical exposure (Treat et al., 2001), and thus, these men may need additional practice in attending to the most relevant dimension. There is some evidence that the gender differences in perception of women’s sexual intent are driven, at least in part, by extreme levels of positive sexual-intent perception among sexually coercive men and men at risk for perpetrating sexual coercion. Given that the evidence seems to support the idea that the sub-group of men most inclined to perceive women’s behaviors as sexually motivated are the same men who are at risk for sexually assaulting women, it becomes particularly important to understand how sexual perception is relevant to their behavior.

5. Situational factors

Even those individuals most prone to sexual coercion are not likely to be aggressive in all situations. The behavior of interest is likely to be quite rare among dating and sexual experiences. For this reason, if sexual misperception is an important predictor of sexual coercion risk, it becomes important to understand more precisely the situations in which sexual misperception is more likely, and those situations in which misperception is less likely, as these situational cues may have implications for prevention efforts. While most of the research examining situational predictors of sexual misperception has not focused on the effect among sexually coercive men in particular, it may be that those factors relevant to misperception in the general population have the strongest effect among sexually coercive men. In any case, as it is clear that sexual misperception is a risk factor for sexual coercion, any factor that increases or decreases the probability of sexual misperception deserves attention. The situational variables that have received the most attention to date are clothing style, dating variables, alcohol use, and attractiveness.

5.1. Clothing style

Evidence suggests that provocative clothing is associated with declining sensitivity to women’s affective cues (Farris et al., 2006). Of interest here, college men become less able to distinguish friendliness from other affective cues when a woman is dressed provocatively; however, their ability to effectively decode sexual interest improves. Thus, while they are less likely to incorrectly categorize a woman who is signaling sexual interest, they are more likely to incorrectly categorize a woman who meant to signal only friendliness (Farris et al.). Contrary to previous speculation, in this study men were generally biased to assume that women’s positive affect cues indicated friendliness rather than sexual interest, but men became more apt to categorize a woman as sexually interested when she was dressed provocatively. Errors in judging sexual interest did not increase with provocative clothing, only errors in judging friendliness (i.e., men were most at risk for misperceiving the intent of women who were attempting to signal platonic interest while dressed provocatively).

In studies that have included both men and women, provocative clothing is associated with increased estimates of women’s sexual intent (Abbey et al., 1987; Cahoon & Edmonds, 1989; Koukounas & Letch, 2001). Interestingly, this effect does not seem to vary as a function of gender. Women were just as prone as men to increasing their estimates of women’s sexual intent when clothing was provocative (Abbey et al.; Cahoon & Edmonds). When asked directly via questionnaire whether clothing style signals sexual intent, most women denied that this is the case. Men were significantly more likely than women to indicate that they believed that clothing choice is used by women to signal sexual intent (Haworth-Hoeppner, 1998). These men will be wrong about this assessment more often than not, as only a small minority of college women (4.3%) indicate that they use provocative clothing as a cue to indicate sexual interest (Perper & Weis, 1987).

As it is possible that clothing style, while less diagnostic of sexual intent than other cues, may be somewhat related to sexual intent, it is important to ensure in experimental tasks that the target set does not contain such a relationship. Treat et al. (2001) developed a stimulus set of women depicted in newsstand magazines and catalogues that were carefully selected in order to span a range along an affect dimension and a physical exposure dimension without introducing a real correlation between the two. Nonetheless, male participants provided ratings that indicated an illusory correlation between physical exposure and target sensuality and sexual arousal.

5.2. Dating variables

Many behaviors associated with dating are perceived as indicators of women’s sexual intent. Of course, if a woman intends for her decision to accompany her date to his apartment to be read as an interest in a sexual encounter, then a man’s interpretation of that cue as sexual intent is not likely to lead to negative outcomes. However, if she genuinely was seeking a quieter place to talk, a reliance on this dating behavior to predict sexual intent will increase the likelihood of an inaccurate interpretation of her behavior. A variety of dating behaviors are associated with an increased perception of women’s sexual intent — some of which seem relatively tangential to intent. Both men and women perceive a female character as more interested in sex if she is initiates the date (Botswick & Delucia, 1992; Muehlenhard, 1988) or is depicted as paying for the dating expenses (as opposed to allowing her date to pay; Botswick & Delucia). Alternatively, conflicting evidence suggests that women are perceived as more sexually disinhibited if the man is depicted as paying for the date (George, Cue, Lopez, Crowe, & Norris, 1995; Muehlenhard). Accompanying a date back to his apartment or dorm room is seen as a signal of sexual intent by both men and women (DeSouza et al., 1992; Muehlenhard). Behaviors such as eye contact, touch, and physical closeness also increase men and women’s judgments of women’s sexual interest (Koukounas & Letch, 2001; but see also Abbey & Melby, 1986). When a woman initiates a date or allows her partner to pay, her behavior is more likely to be judged as indicating sexual interest, and unfortunately, is also associated with an increased willingness to indicate that raping the woman would be justified (Meuhlenhard; Muehlenhard, Friedman, & Thomas, 1985).

5.3. Alcohol

In 30% of sexually coercive incidents and 59% of attempted or completed rapes, alcohol use by the man, woman, or both partners is reported Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McAuslan, 1996a; see also, George & Stoner, 2000). However, alcohol consumption also is linked with consensual sexual activity (Prince & Bernard, 1998). The relationship between alcohol and sexual coercion may be mediated by a separate underlying mechanism. One reasonable hypothesis is that alcohol increases the risk of sexual misperception, which, in turn, may increase the risk of sexual aggression.

Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McAuslan (1996b) proposed a model of sexual aggression that included just such a pathway. Their hypothesis was supported by a structural equation model, which demonstrated that usual alcohol consumption among college men increases the reported frequency of misperception of a women’s sexual intent, which in turn, predicts the number of sexual assaults perpetrated (Abbey et al., 1998). The complete model also included dating and sexual experiences, rape-supportive beliefs, and alcohol expectancies. The model explained 28% of the variance in the number of sexual assaults reported by college men.

Given that ‘usual alcohol consumption’ does not necessarily imply that sexual misperception occurs concurrently with alcohol use episodes–perhaps those who use alcohol are more likely to misperceive sexual intent even during periods of sobriety–a follow-up study employed an event-level analysis of dates that involved sexual aggression versus dates that were just “bad” (Abbey et al., 2001). Men who had perpetrated sexual aggression reported more alcohol use on occasions when they misperceived a woman’s attempt to be friendly as a sexual come-on. They were also more likely to report sexual misperception on dates that involved sexual aggression than on dates that were bad, but did not end in sexual violence, suggesting that there may be an event-level relationship between alcohol intoxication, sexual misperception, and sexual aggression.

Of course, experimental manipulations would provide the most convincing evidence that acute alcohol intoxication influences sexual perception. Across multiple investigations, results typically have supported this conclusion. Men who consume a moderate alcohol dose in a laboratory setting perceive a female confederate as behaving in a more sexualized manner and recall relatively more of her positive cues than her negative cues, as compared to men who consume a placebo dose or a known nonalcoholic beverage (Abbey et al., 2005). Alcohol-intoxicated men also perceived an unacquainted woman as more disinhibited and sexual (Abbey, Zawacki, & McAuslan, 2000). Non-intoxicated men distinguished women who behaved in an attentive manner from women who were inattentive (as categorized by external coders), and they believed the attentive women were more sexually attracted to them. In contrast, intoxicated men made no such distinction (Abbey et al., 2000). Their ratings of the woman’s sexual attraction did not depend on her attentiveness, suggesting that alcohol may have reduced attention to important behavioral differences (Abbey et al., 2000).

There are at least two major points at which alcohol may influence men’s sexual perception. The first, as discussed above, is the influence of men’s alcohol use on their perception of women. The second is the influence of women’s drinking on others’ perception of their sexuality. In general, when women are portrayed drinking alcohol they are rated as more sexually interested, sexually disinhibited, and possessing greater sexual initiative than women who are portrayed drinking a nonalcoholic beverage (Corcoran & Thomas, 1991; DeSouza et al., 1992; Garcia & Kushnier, 1987; George, Gournic, & McAfee, 1988). These ratings of sexuality increase linearly as the alcohol dose increases (George et al., 1997). The effect has also been demonstrated in a laboratory setting in which male participants interacted with unacquainted women (George, Stoner, Norris, Lopez, & Lehman, 2000). The effect is not a simple one, however. For example, Abbey and Harnish (1995) reported that ratings of a woman’s sexuality were highest when she was drinking along with her male date, but ratings of her sexuality were lowest when she was drinking alone while her date abstained (see also Leigh et al., 1992). Others have reported that only men with strong expectancies that alcohol will increase sexuality and disinhibition perceive drinking women as being more sexually available than non-drinking women (George et al., 1995). Men who generally reject the notion that alcohol increases sexuality are unlikely to change their perception of women’s sexuality when women drink versus abstain (George et al.). Finally, Leigh and Aramburu (1996) found no evidence for such a relationship. A female character’s alcohol use did not influence men’s ratings of her perceived willingness to engage in sex.

The influence of alcohol use has been one of the most frequently studied factors in the study of increased risk for sexual misperception. The study of alcohol’s influence on heterosocial perception ranges from survey research to alcohol use manipulations in the laboratory. Abbey and Harnish (1995) provide a narrative summary of the relationship between alcohol, misperception, and sexual aggression:

The finding that alcohol consumption is perceived as a sexual cue, suggests that alcohol increases the likelihood that a woman’s platonic friendliness will be misperceived by a male companion as a sign of sexual interest. The cognitive impairments associated with alcohol consumption can, in turn, make it difficult for a woman to rectify misperceptions and to effectively resist unwanted sexual advances. Consequently, alcohol makes it more probable that misperceptions will become sexual assaults, either because a man mistakenly believed that his female companion really wanted to have sex or because he felt that she led him on to the point that force was justifiable (Goodchilds & Zellman, 1984; Muehlenhard, 1988) (p. 310).

5.4. Attractiveness

Given the expanse of literature outlining the influence of attractiveness on social perception (Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991), we might expect that individuals will perceive an association between a woman’s attractiveness and her degree of sexual interest or intent. Alternatively, if sexual intent is considered a negative attribute, then perhaps the relationship would be reversed. Unfortunately, this has not been a well-studied area of investigation. However, one compelling and well-designed study deserves particular attention (Maner et al., 2005). After viewing a romantic video clip or a frightening video clip, participants rated the emotions portrayed by individuals in a series of photographs. Although all the faces depicted a neutral facial expression, participants were instructed to determine the underlying emotional state of the person pictured in the image and rate the degree to which the person was sexually aroused, happy, angry or frightened when the picture was taken. Results were quite specific to condition. Caucasian male participants who were primed with a romantic video clip saw more sexual arousal in Caucasian, attractive, female faces than males in the control condition. Note also that participants perceived more sexual arousal in same-race, attractive, women; the result did not generalize to male faces, unattractive faces, or non-Caucasian faces. In addition, only men primed with romantic cues perceived greater sexual arousal in neutral faces, and this was not due to a general increase in perception of positive affect, as perception of happiness did not increase. Both female and male participants who were primed with a frightening video clip did not see more sexual arousal in the faces than participants in the control condition. In addition to highlighting the specificity of perception of sexual arousal, Maner et al.’s (2005) work also suggests that target attractiveness may play an important role in understanding when men are most likely to overestimate the degree of a woman’s sexual intent.

5.5. Summary

Evidence assembled to date suggests that several situational factors may increase the risk that men will misperceive women’s sexual intent. Clothing styles that are more revealing or provocative, dating behaviors such as returning to an apartment after a date, alcohol use either by the perceiver or the perceived, and women’s attractiveness all seem to increase sexual misperception. We can speculate that these factors are at least as relevant to the prediction of sexually coercive men’s social perception as they are for non-coercive men. However, future research outlining the specific nature of situational predictors of sexual misperception among sexually coercive men will be important in specifying the best intervention targets. The relationship between context and misperception may well be moderated by individual differences in risk for sexual aggression. Finally, in order to effectively guide intervention targets, it will be important to know if situational contexts influence sexual perception by shifting decision criteria or by reducing sensitivity.

6. Linking sexual misperception and sexual coercion

Misperception of women’s sexual intent certainly will not cause men to behave in a sexually coercive or aggressive way in all cases. Yet, it is also clear that the two variables do covary to some extent. Several plausible interpretations of the relationship have been posited. First, it is possible to argue that the two have no real relationship at all, and instead, that a relationship is constructed after an assault in order that a perpetrator may absolve himself of guilt (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999). “Miscommunication” becomes a post-hoc excuse for the behavior after the assault has occurred, which creates a spurious relationship unreflective of real-time processes. This dismissal of misperception certainly could explain studies that report an association between self-reported sexual misperception and self-reported sexual coercion. The participant may see misinterpretation of women’s sexual intent or consent as a more flattering interpretation of his behavior and be happy to endorse the construct. However, if the relationship is indeed spurious, then the relationship should emerge only in studies that rely on self-report and not in those research programs that rely on performances measures of sexual perception. That is, if men are processing sexual intent accurately, and if self-reported inaccuracy is merely self-protective, then direct performance measures of men’s sexual perception should be unrelated to sexual aggression history. This is not the case. When men are required to make rapid, repeated judgments of women’s sexual intent as displayed in photographs, performance deficits are linked to sexual coercion risk and history (Farris et al., 2006). While it is certainly the case that sexually aggressive men may rely on misperception to exculpate their guilt for their behavior, the evidence currently supports the possibility that there is also a real relationship between men’s ability to decode women’s sexual interest and the likelihood of sexual coercion.

If we do not dismiss the relationship between sexual misperception and sexual coercion, there seem to be at least three plausible narratives linking the two. First, coercive men’s judgments about women’s sexual consent may be significantly influenced by a context involving prior misperceived sexual interest. Research suggests that women attempting to signal non-consent to a valued relationship partner often use non-consent cues laced with ambiguity such as physical avoidance and with verbal cues such as “I’m not in the mood right now” (McCormick, 1979). If a man is making a judgment about consent without prior reason to believe his partner is sexually interested, he may be quite likely to decode non-consent accurately from these ambiguous cues and discontinue sexual advances (e.g., men decoding consent from questionnaires in the non-sexualized environment of the laboratory decode ambiguous non-consent cues quite accurately (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999). However, consider the situation faced by an inaccurate male partner who mistakenly has decoded sexual interest earlier in the interaction. Based on mistaken information about his partner’s interest, he may be more likely to interpret the same ambiguous non-consent cues as token resistance and continue making sexual advances despite his partner’s non-consent, believing that the true internal motivation of his partner is to pursue a sexual encounter. These men may believe that the sexual coercion that they perpetrate is seduction. In sum, the context of (mis)perceived sexual interest may influence gravely the crucially important step of decoding sexual consent, which in turn may lead to the perpetration of sexual violence.

Alternatively, sexually coercive men may decode women’s non-consent accurately, but the prior context of misperceived sexual interest may make it more likely that they nonetheless choose to aggress against their partner. In this case, prior misperception of sexual interest may increase the expectation that a partner will respond to sexual advances with consent. When a sexually coercive man instead receives (and accurately decodes) non-consent cues from his partner, this unexpected outcome may seem arbitrary and hostile. Given that he believed that her behavior indicated interest, the new information that she will not consent to a sexual encounter may be interpreted as a deliberately antagonistic choice. In fact, many sexually coercive men do endorse a similar interpretation of the events leading to their violence, reporting that their partner “led them on” prior to the assault (Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987). In this second interpretation of the link between sexual misperception and sexual violence, the context of early misperception of sexual intent serves to change the interpretation of the motives behind non-consent. Without the early misperception, non-consent will be interpreted as consistent with the woman’s prior behavior and may be more likely to be honored, but given misperception, her behavior may seem inconsistent. Of course, even in this situation, while many men may respond with frustration, most will not subsequently choose aggression. However, a sub-group of men, who are predisposed to react to frustration with aggression due to other individual-difference variables (Berkowitz, 1989), may choose to aggress against the object of their frustration, in this case, their partner. Given that the context of the frustration is sexual, it should be expected that the form of aggression also will be sexual.

Finally, the association between sexual misperception and sexual coercion may be quite simple. Men who are heterosocially skilled may be accurate in decoding both women’s interest cues as well as women’s consent cues. Similarly, men who are generally heterosocially unskilled may have skills deficits that cut across decoding of interest as well as consent. That is, it may be that skill in decoding early interest is not independent of skill in decoding later consent. The two may covary, and thus, create a relationship secondary to an underlying general skills deficit.

Sexual aggression is a multi-determined phenomenon, with many paths leading to the same behavior. As such, the suggestions posited above as plausible explanations for the relationship between sexual misperception and aggression are not mutually exclusive from other pathways to the behavior. For many sexually aggressive men, sexual misperception may be entirely irrelevant to perpetration (e.g., among men who commit premeditated offenses). And among those men for whom it is relevant, it may be related in different ways. That is, the context of early sexual misperception may cause dismissal of non-consent as merely token resistance for some men; while for other sexually aggressive men, sexual misperception may not interfere with accurate decoding of consent, but nonetheless creates a context in which non-consent is viewed as purposely inciting frustration, and thus, justifying violence.

7. Clinical implications

Sexual coercion prevention efforts may take two primary forms — targeted intervention with high-risk men or blanket approaches covering entire populations. Large programs designed to target all men have been popular on college campuses. Early sexual aggression theories classified all men as potential perpetrators (McKinnon, 1987), and some have indicated that the rate of sexual coercion among college students calls for universal prevention efforts (Abbey et al., 2005). This framework has been largely responsible for the implementation of sexual-assault prevention programs for college students, which typically consist of short lecture or videotaped programs lasting less than 2 h (Lonsway, 1996; Yeater & O’Donohue, 1999). These programs have provided encouraging evidence suggesting that their efforts reduce sexual coercion correlates such as acceptance of rape myths (Davis & Liddell, 2002; Heppner, Humphrey, Hillenbrand-Gunn, & DeBord, 1995). These gains largely disappear within months of the intervention, however (Breaklin & Ford, 2001; Davis & Liddell; Heppner et al.). Moreover, the few studies that have examined actual perpetration rates have found no differences in rates between populations that received the intervention and those who did not (Foubert, 2000; Heppner, Nelville, Smith, Kivlignhan, & Gershuny, 1999). Furthermore, conflicting evidence suggests that the short-term gains previously reported may be attributed primarily to low-risk men (Gilbert, Heesacker, & Gannon, 1991). Although O’Donohue, Yeater, and Fanetti (2003) found that high-risk men responded favorably to a prevention program, a Stephens and George (2004) intervention study found that those men whose attitudes and prior perpetration history indicated the highest risk for future perpetration were unresponsive to the intervention. In sum, prevention efforts with men have been disappointing to date (Yeater & O’Donohue, 1999).

In the future, it will be important to increase efforts in the basic-science sector to further the understanding of the etiology of sexual coercion in order to better direct the form of intervention. The evidence supporting the link between sexual misperception and sexual coercion points to one marker of risk and potential pathway to negative behavior. By pursuing this direction in order to more fully understand processing mechanisms leading to the observed perceptual errors, we may develop the necessary knowledge to direct the form of prevention more precisely. For example, theoretical interpretations of dissimilar perception of sexual interest by non-coercive and coercive men have included both differences in sensitivity between the groups, perhaps reflecting a genuine inability to discriminate friendliness from sexual interest, as well as differences in decisional thresholds between the groups, such that coercive men require fewer impelling cues before assuming a woman is signaling sexual interest. By employing performance-based, cognitive modeling techniques, Farris et al. (2006) provided early evidence that sexually coercive men may have a skills deficit in reading women’s affective cues (i.e., an insensitivity to important distinctions between affect categories). This type of evidence may help to direct prevention programs to focus on skill building within the realm of affect recognition, rather than increasing the decisional boundary for identifying sexual interest. Allowing basic science to catch up with prevention program design may provide program developers with the data necessary to pinpoint the mechanisms supporting and leading to sexually coercive behavior, and therefore, provide a better hope of developing an effective prevention program.

Not all men are prone to sexual misperception, and among those who are, most will not respond to misperception of sexual intent with aggression against their partners. Combined with some evidence that high-risk men may be less likely to be influenced by prevention programs (Stephens & George, 2004), one implication is that an alternative prevention design would redirect resources from low-risk men to efforts to understand and effectively intervene with high-risk men. The thread connecting misperception of sexual intent and sexual aggression provides one marker of risk that may serve to identify those men for whom intervention is most critical. Once identified, one element of a comprehensive prevention program might focus on decreasing the risk of sexual aggression by reducing the incidence of sexual misperception, or in the event that sexual misperception does occur, by breaking the link between sexual misperception and aggression.

To do so, one approach would introduce didactic material designed to modify problematic decisional criteria or enhance sensitivity into current presentations provided by existing prevention programs. Given the developed infrastructure for these efforts, this would be a relatively simple and low-cost alternative. Thousands of college men already are served by these programs, and information regarding the risk of sexual misperception could be easily integrated into existing psychoeducational formats. It is perhaps more reasonable to expect that these formats would have the potential to shift men’s decisional criterion for sexual interest, rather than to enhance their sensitivity to sexual interest. If basic research suggests that the overuse of the sexual interest category is due to a liberal threshold for labeling sexual interest, the relative payoff structure for correctly detecting sexual interest versus incorrectly assuming that a woman is sexually interested when she intended to convey only friendliness (a false alarm) may need to be shifted. A liberal threshold reflects a preference for mistakes that are false alarms (mistakenly calling a friendly woman sexually interested) over misses (failing to detect a woman who is sexually interested). An intervention may consist of urging a man to shift his criterion by placing greater value on false alarms than misses. If false alarms increase the risk of sexual aggression and associated social and legal consequences, then it may be possible to retrain high-risk men to trade detection of some sexually interested women for safety from false detections. In may also be possible to do so within the lecture or video formats currently favored in sexual-assault prevention programs. However, we should be concerned that high-risk men do not seem to respond to these formats (Stephens & George, 2004), and that potential legal consequences may not serve as a deterrent to risk-taking individuals high in sensation seeking (Zuckerman, 1994). Alternatively, if errors in detecting sexual interest are not due to decisional processes (bias), and instead reflect genuine insensitivity to women’s affect cues (a skills deficit), then it seems unlikely that telling an unskilled individual to become more skilled will be effective. In this case, it may be necessary to provide perceptual training, in which participants repeatedly make judgments about women’s affect and receive immediate feedback about accuracy. This type of non-verbally mediated strategy could be developed either to re-shape decision boundaries or to enhance sensitivity, depending on person-specific deficits.

Individualized treatment offers the advantage of personalized assessment of accuracy in decoding sexual interest. Many men may be unaware that their perception of women’s sexual intent is inaccurate, and thus, may not identify with educational messages about misperception. Instead, performance-based measurement and modification of men’s accuracy in judging women’s sexual intent would be a preferred tool for individualized assessment and intervention with high-risk men. Access to normative performance on similar tasks would allow clinicians to compare the performance of an individual to the performance of his peers. Non-judgmental review of discovered deficits relative to peers may function similarly to the motivational interviewing approaches that have been employed so successfully with other problem behaviors, such as alcohol use problems (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). For example, among alcohol users, review of drinking behavior relative to population norms has proved to be an effective tool in motivating and creating change. Likewise, providing a standard of men’s normative performance in decoding women’s affect (and interference from non-relevant factors such as clothing style) may allow high-risk men to contrast their performance and behavior against population norms, instead of the more skewed feedback they may receive from deviant peer groups.

The form that retraining of sexual misperception would take depends largely on uninvestigated questions regarding the type of perception errors that lead to the inaccurate categorization of a woman’s intent. For example, if men’s over-utilization of a sexual interest category reflects insensitivity to the distinction between women’s platonic and sexual interest cues, then repeated training with accurate feedback may be an intervention possibility to pursue. Roughly speaking, this might consist of repeated trials in which an image of a same-aged female peer is presented, judgments of sexual interest or friendliness are scored incorrect or correct based on normative peer consensus, and performance is retrained to meet a criterion. Alternatively, if overuse of the sexual interest category is due to a liberal threshold for labeling sexual interest, the relative payoff structure for correct detections of sexual interest versus false alarms may need to be shifted, as discussed above. That is, the cost of falsely labeling a friendly woman as sexually interested could be quite high, either by emphasizing legal/social repercussions or by implementing direct costs through a monetary or point reward system in the retraining program. Whether directed retraining of social perception will reduce sexual misperception, and whether reduced sexual misperception will impact the real target of sexual coercion, remains largely speculative. Nonetheless, the available literature indicates that sexual misperception is a sensible intervention target. Future research will need to provide the evidence as to whether a sensible target is indeed a malleable and effective target, and whether it provides added utility as an additional component to a comprehensive intervention program.

8. Conclusion

Men’s perception of women’s sexual interest has been well-investigated both within the context of gender differences, as well as within an individual-differences context as related to sexual aggression. It appears safe to conclude that men are likely to perceive a female target to be displaying more sexual interest than women will perceive in her display, and that some situational factors will increase further estimates of sexual interest. The evidence indicates that some, if not most, of the gender difference can be attributed to a sub-group of men high in risk factors for sexual coercion. Indeed, sexually coercive men perceive more sexual interest in female targets than non-aggressive men, and this misperception of intent may provide the context in which to situate later decisions to aggress against a dating partner.

These conclusions do not represent a finale to a research literature. Rather they provide only a preliminary foundation on which to build. Currently, little is known about the origin of errors in sexual perception. If errors are due to evolutionary pressure, as some have suggested (Haselton & Buss, 2000), perceptual processes may prove resistant to intervention. Alternatively, if social processes or individual learning histories are responsible for misperception and sexual coercion, intervention and prevention strategies may employ behavioral and cognitive intervention designed to replace or change early learning. In either case, changing sexual perception, and more importantly, sexually coercive behavior depends in part on the individual’s motivation to change. Future research investigating questions of origin, motivation to change, and response to intervention may exert a direct and important influence on applied prevention strategies.

Returning to the primary findings regarding sexual misperception, the conclusions specified have been built upon a measurement strategy that involves comparing group means, which unfortunately does not allow important theoretical questions regarding the source of the errors to be answered. Although we can be relatively confident that men and women differ in their perception of sexual interest, and that sexually coercive and non-coercive men also differ, we are unable currently to be sure of the source of these discrepancies. Whether it lies within the realm of insensitivity to affect category distinctions or represents decisional bias is largely unexplored. In the future, it may be important to focus on forms of measurement and research designs that can begin to explicate this question. For example, shifting to performance-based perception measures and asking participants to complete the large number of trials necessary to establish reliable estimates of skill would carry the advantage of allowing access to the computational models of simple perception developed by cognitive scientists. Perhaps by moving away from describing observed differences between coercive and non-coercive men, and toward a description of underlying processes, we will better understand the precise form of perceptual errors that lead to sexual misperception, which in turn will allow a more studied approach to intervention development. By creating the basic-science foundation to sexual aggression etiology, applied efforts may meet with more success. Understanding errors in sexual perception ultimately may play an important role in reducing the incidence of sexual aggression.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32-MH17146) and the National Institute of Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (F31-AA016055).

SDT has several competing models that also can differentiate error due to insensitivity from error due to decisional bias. These alternative models include Choice Theory (Luce, 1959; 1963), regression approaches (DeCarlo, 1998), and General Recognition Theory (Ashby & Townsend, 1986; Kadlec & Townsend, 1992); the latter provides a generalization of SDT that can be applied to tasks that involve identifying stimuli that differ on more than one dimension.

References

- Abbey A. Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females’ friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;42:830–838. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A. Misperceptions of friendly behavior as sexual interest: A survey of naturally occurring incidents. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1987;11:173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Cozzarelli C, McLaughlin K, Harnish RJ. The effects of clothing on dyad sex composition on perceptions of sexual intent: Do women and men evaluate these cues differently? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17:108–126. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Harnish RJ. Perception of sexual intent. The role of gender, alcohol consumption, and rape supportive attitudes. Sex Roles. 1995;32:297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAusland P. A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perception of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]