Abstract

Background:

While previous research has established a link between socioeconomic status (SES) and cancer outcomes, there is still little understanding of the processes that contribute to these outcome disparities.

Objective:

This study aims to describe the ways a family's socioeconomic status (SES) influences their health care behavior after a child is diagnosed with cancer.

Methods:

The sample included five case study families and in-depth interviews with 21 parents. Case study families were interviewed and observed once a month for six months.

Results:

Parents' finances influenced their ability to maintain household expenses, and to pay for health care expenses and household help. Wealth and help from friends and family are important aspects of families' financial statuses. Parents' educational attainment affected their ability to understand diagnosis and treatment options, their confidence and communication with health care professionals, and the utility of their social networks. Parents' occupation influenced their work schedule flexibility, fringe benefits, and their access to and quality of employer-sponsored health insurance.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that three overarching domains of SES (e.g. financial, education and occupation) have important implications for parents' health care navigation. This study underscores the need to use a nuanced set of SES measures (beyond income and education) in future research to enhance our understanding of how SES affects health care navigation, and refine intervention initiatives designed to help reduce health disparities.

Implications for Practice:

Cancer education initiatives should focus on enhancing patient-provider interactions, health communication, accessing health information, and resolving work and financial barriers to cancer care.

Introduction

Research identifying cancer health disparities has become increasingly prominent within the literature on the epidemiologic and social determinants of cancer outcomes.1-4 While the positive association between SES and health outcomes (such as, five-year survival after a cancer diagnosis) is well documented in the cancer literature, researchers continue to strive to understand the complex processes that contribute to this link.5-8 While large population based studies have established a growing body of evidence of an association between SES and health outcomes, many scholars have identified a need to understand what aspects of SES contribute to this observed link on an individual level.6,9 A major focus of this new body of research is to understand more about the processes through which individuals translate resources into health advantage.10-13

This shift in research aims – from attempting to understand the macro association between SES and cancer outcomes, to documenting the processes by which disparities are produced – requires an empirical shift in the way SES is conceptualized and measured in research. SES is often difficult to operationalize in nuanced ways in health-related studies.14 Many previous studies are limited by their measurement of SES, commonly using only income or education as a proxy for SES.14 Research seeking to understand the processes underlying health disparities needs to account for the multi-faceted ways that SES influences individuals' lives. SES represents a range of theoretically important dimensions beyond income and education, including: social networks, social position, job flexibility, neighborhood characteristics, liquid assets (easily accessible money, such as personal savings) and wealth (total value of possessions, real estate holdings, equity in business ventures, personal savings and investments). It may be that it is precisely these dimensions that play important roles in patients' abilities to navigate the health care community after a cancer diagnosis. Yet, researchers still do not have a complete understanding of how individuals translate SES-related resources into health advantage, the barriers to cancer care that low SES presents, and opportunities to target these barriers through intervention initiatives.

Methods

The Case: Pediatric Cancer

Access to quality cancer care is one commonly examined pathway that links SES to health outcomes.5 Yet, an individual's SES is likely to influence their health care experiences beyond access to care, and we have very little understanding of how these processes work. This exploratory research examines the health care navigation of individuals of high and low SES who have access to the same cancer care resources. Of the major cancer sites, pediatric cancer presents a unique opportunity to examine the effect of SES on patterns of health care navigation while reducing the variability in two known SES-related barriers to care that have been identified in previous literature – insurance status and site of care.5

In the study area (New York State), children with cancer from low income families are eligible for Medicaid health insurance benefits that are quickly rendered, and provide coverage that is comparable to most standard health insurance plans. This enables children from low-income families in the study city to receive cancer care in the same hospital settings as children from high-income families. All families in this study had children who were treated for cancer at one of two hospitals in the same city. Due to this unique patterning of care for pediatric cancers, we have the opportunity to examine parents' patterns of navigating the same health care settings after a child is diagnosed with cancer.

Study Design

This study used well-established qualitative techniques to gather rich and in-depth data on families' patterns of health care navigation.15 It combines ethnographic case studies of five families in which a child was currently undergoing active treatment for cancer, with in-depth interviews with an additional thirteen parents of pediatric cancer patients. A qualitative design is appropriate due to the exploratory nature of this study. SES affects individuals' lives in complex ways that are often beyond the level of conscious decision-making. Due to this, the relationship between a person's SES and their behavior may be difficult for them to articulate. A qualitative study design that combines longitudinal observation with in-depth interviews allows us to describe these complex processes as they naturally occur, rather than asking participants to reflect upon them using hypothetical situations. Written informed consent was obtained from all case study and in-depth interview participants for this IRB approved study. The interviewer reviewed the informed consent with each participant, and offered time for participants to read the full consent document and consider participation before consenting to the interview. The consent form obtained permission to include respondent's views and experiences in the study. The informed consent also assured respondents that every effort would be made to protect their confidentiality. Due to this, all information that could link specific patients, clinicians, and hospitals to these data have been removed. Real names have been replaced by pseudonyms, and some non-consequential details of families have been modified or omitted. All individuals present during observations were asked for their verbal consent at the beginning of each observation.

Ethnographic Case Study Methodology

Ethnographic case studies provide an opportunity for researchers to observe families in their normal daily routines while also building rapport between researchers and respondents, making respondents more comfortable revealing personal and sensitive information.16 The ethnographic method emphasizes a holistic orientation to collecting data. A core dimension of ethnography is to provide a complete and nuanced understanding of an individual's experience, as well as the context in which those experiences occur. In a pure ethnography, the research design and goals are constantly evolving as data is collected, analyzed, new research questions emerge, and the researchers modify data collection strategies. This study had specific research goals, and due to this, the design was established before entering the field. Therefore, it combines a case study methodology guided by an ethnographic approach with in-depth interviews. The case study approach allows a small number of families (cases) to be examined in-depth over a period of time. Participant observations, which were a central form of data collection for the case studies in this research, involve the researcher participating in activities along side the respondents as a means of collecting data on these experiences. In this study, those activities ranged from watching a television program with a family in their home, sitting with a parent and child in the chemo infusion clinic, and accompanying a family to an appointment to enroll in social services. Observations were guided by widely-used qualitative observation practices, and the researcher paid particular attention to the physical layout of the environment or place, range of people involved, sets of related activities that occurred, the physical things that were present, single actions people undertook, activities that people carried out, the sequencing of events that occured, things that people were trying to accomplish, and the emotions that were felt and expressed.17 Because these observations are all filtered through the point of view of the researcher, ethnography emphasizes the process of reflexivity in which the researcher continuously reflects on their potential biases and personal experiences, and attempts to incorporate this self-awareness into their reporting and analysis of observation data. Ethnographic research is inductive, which means that codes, themes and theories emerge from the data, rather than the study being designed to test a predetermined set of hypotheses.

Case Study Data Collection

For the first part of the study, five socioeconomically diverse families were selected from the patient pool at a local home care nursing agency. The medical social worker approached parents in each family, introduced the research to parents, and asked their permission to forward their information to researchers. All families who were initially approached agreed to participate in the study. The families were then contacted, and an appointment was scheduled to interview and observe them in their homes (Table 1). Families' participation in the research began with an in-depth semi-structured interview with parents. When two parents in a family were available to participate, each parent was interviewed separately. Interview times ranged from thirty-five minutes to two hours, but typically lasted just under an hour. All interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriptionist. The parents were then asked to allow the researcher to stay with them in their homes and observe their family. During periods of observation, the researcher made efforts to be as unobtrusive as possible, attempting to fade into the background of the setting. This was typically possible since most families were used to having outsiders in their daily lives due to their child's cancer care. The researcher took jotted notes to assist recall of events, and observations were audio-recorded when possible. One researcher, who had experience and training in qualitative data collection, conducted all interviews and observations. The researcher collecting the data did not know any of the participants prior to the study. The researcher had no clinical training or experience, and made it clear to respondents that they were not familiar with many practices in the health care community. This enhanced the researcher's ability to ask naive questions, and allowed the respondents to explain seemingly mundane aspects of their child's medical care. Each family was followed-up once a month for six months. At weeks 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 the research team contacted each family and scheduled a follow up interview and observation. At each follow-up, parents were re-interviewed to capture events that had occurred during the past weeks. The families were then observed for three to four hours. Follow up observation locations varied due to differences in family routines and the child's treatment plans; however, each family was observed in their homes, and while at a hospital clinic, or while their child was admitted to the hospital. After each observation, the researcher immediately dictated notes into a tape recorder, and later wrote in-depth field notes. Field notes were added to transcripts to form the data file for each family.16 All audio files were transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriptionist. The researcher who conducted all interviews and observations then carefully reviewed each transcript while listening to the audio recording to check for accuracy. The total case study data set consists of thirty in-depth interviews with parents and over ninety hours of observations.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Five Case Study Families

| Family 1 | Family 2 | Family 3 | Family 4 | Family 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Marital Status |

Married | Married | Married | Divorced | Never Married |

|

Parent Recruited to Study |

Mother and Father |

Mother; father declined to participate due to work schedule constraints |

Mother and Father |

Mother and Father |

Mother; father does not maintain an ongoing relationship with children |

|

Number of Children |

2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

|

SES Variables |

|||||

| Education | Both mother and father have advanced degrees |

Both mother and father have advanced degrees |

Father has college degree; Mother has associates degree |

Both mother and father have high school degrees |

Mother has not completed high school; Father's education unknown |

|

Household Income |

> $34,500 | > $34,500 | > $34,500 | < $34,500 in each household |

Completely supported by public assistance |

|

Occupational Status |

Mother has never worked outside of home; Father has high SES occupation |

Father has high SES occupation; Mother had high SES occupation prior to leaving the workforce to care for child with cancer |

Father has high SES occupation; Mother had low SES occupation prior to leaving the workforce to care for child with cancer |

Both mother and father have low SES occupations |

Mother had low SES occupation prior to leaving the workforce to care for child with cancer |

|

Home Ownership |

Own home | Own home | Own home | Both mother and father rent homes |

Mother and children live in government subsidized housing |

Exact income levels and occupations have been removed to protect respondent confidentiality.

One-Time In-depth Interviews

To ensure that the experiences of the five case study families were not idiosyncratic to these particular families, one-time in-depth interviews were conducted with additional families who had a child who had been diagnosed with cancer. The sampling strategy was modified for the one-time in-depth interview portion of the study. Some respondents were identified through the same home care nursing agency as the case study families. To capture a larger group of families of pediatric cancer patients, flyers were also distributed in mailings of local pediatric cancer charities. Respondents contacted the research team by telephone or email after seeing the recruitment flyers. The sample for the in-depth interview portion of the research was a convenience sample. One parent from each family was recruited for the one time in-depth interviews. The total in-depth interview sample consisted of three fathers and ten mothers. One family identified as Hispanic, and all others were white.

Interviews followed a discussion guide used for the first interview with each case study family, and the discussion guide was also modified before the one-time in-depth interview portion of the study to capture themes that had emerged through the ethnographic case studies. The discussion guide consisted of open-ended questions. Questions were designed to serve as broad topic prompts to encourage respondents to talk about different aspects of their experiences caring for a child with cancer (for example communicating with health care professionals and balancing work and their child's care). Interviews were semi-structured, so the questions on the discussion guide served as starting points, and the interviewer asked follow-up questions to capture each respondent's unique experiences. The semi-structured interviews allowed each respondent to discuss their experiences, while also ensuring that all interviews covered the same set of topics of research interest. Interviews were conducted until data saturation occurred (each new interview replicated themes already revealed in previous data collected).16 After thirteen interviews, data analysis revealed that the later interviews repeated themes that had emerged in previous interviews, and failed to produce new themes surrounding SES and health care navigation. After each interview, the researcher wrote in-depth field notes, which documented their communication with the respondent before the interview, a description of where the interview took place, their interactions with the respondent, and any non-verbal communication that occurred throughout the interview.

Data Analysis

Once interviews were transcribed, a data file consisting of the field notes and interview transcript for each interview was created. Each interview transcript and accompanying notes were read several times by the researcher and a research assistant. The qualitative software program Atlas.ti was used to code each interview.18 Codes were used to identify portions of interview or observation data that captured information surrounding topics pertinent to the research questions. Two members of the research team coded each data file. Meetings were held to review and share coded data, and inter-coder reliability was assessed. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed and resolved.

Following well-established measurement of SES in previous qualitative research,19 families were classified according to four dimensions of SES: income, home ownership, education, and occupational status (Table 2). Table 3 reveals the sample characteristics across these dimensions of SES. Data analysis began with each member of the research team carefully reading all transcripts and field notes in their entirety. Careful attention was paid to themes that emerged from the data. Data analysis was approached inductively, and the identification of themes, the meanings and experience of themes for different groups of respondents, and the relationship between codes and themes were all allowed to emerge from the data. During data analysis researchers made notes about how codes, themes, and relationships were identified, and the researcher's reflections on the data as it was analyzed. These notes served as an important tool in identifying overarching patterns in the data, and linking data findings to theory development.

Table 2.

Conceptualization of SES

| High SES | Low SES | |

|---|---|---|

| Income | > $34,499 annually | < $34,500 annually |

| Education | Bachelors degree or more | Less than bachelors degree |

| Occupational Status |

Has managerial authority, draws upon complex skills |

Does not have managerial authority, or draw upon complex skills; unemployed |

| Home Ownership |

Owns home | Does not own home |

Table 3.

Percentages of Total Sample of Families on Four Dimensions: Income, Home Ownership, Education and Occupational Status (N in parenthesis)

| High SES | Low SES | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 56% | 44% | 100% |

| (High >$ 34,500) | (10) | (8) | (18) |

|

| |||

| Home Ownership | 67% | 33% | 100% |

| (High = Owns Home) | (12) | (6) | (18) |

|

| |||

| Education | 67% | 33% | 100% |

| (High = Bachelor's Degree or more) | (12) | (6) | (18) |

|

| |||

| Occupational Status | 50% | 50% | 100% |

| (High = At least one parent has job which draws upon complex, education derived skills, or managerial authority) | (9) | (9) | (18) |

Results

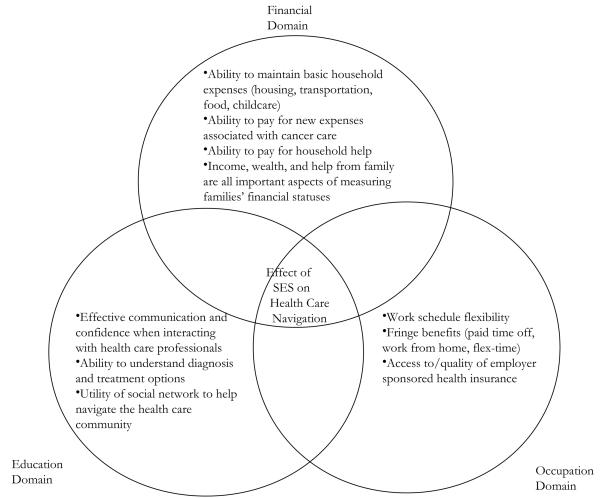

Findings suggest that the SES construct represents numerous different variables that influence individuals' health seeking behavior. Three overarching domains of SES that influence the patterns of health care navigation of parents of pediatric cancer patients emerged from the analysis of data: the financial domain, the education domain, and the occupation domain (Figure 1). The following section describes the specific ways that each SES dimension influenced respondents' health care navigation.

Figure 1.

The Theoretical Importance of Finances, Education and Occupation for Understanding the Link between SES and Health Care Navigation

Financial Domain

The volatile nature of parental income and the important buffering effect of wealth

Findings suggest that there are two major elements of a family's financial status – income and wealth – that have implications for their patterns of health care navigation. One of the most common themes that emerged from qualitative data analysis was the importance of household finances in fostering opportunities, or leading to barriers, for parents' patterns of health care navigation after a pediatric cancer diagnosis. Every parent who had a household income below the mean for the study city (less than $34,500 annually) discussed financial difficulties associated with their child's care. These obstacles included an inability to afford expenses related to housing, transportation, food bills, health insurance co-payments, and childcare. One low-income mother explains, “I was literally coming out of [the hospital] garage at night, freezing temperatures, and my car wouldn't open or it wouldn't start.” Analysis of field notes shows that low income parents spent a large proportion of observed interactions with the medical social worker, nurses, and physicians discussing solutions to financial obstacles, while financial issues were only discussed with a medical professional once in an observed interaction between a high income parents and the medical social worker.

Household income often changed significantly throughout the period of cancer treatment for respondents in this sample, making accurate reporting of income-related figures difficult for parents. One mother whose experience was representative of many other parents explains, “I was making over $40,000 a year, but when she was diagnosed I quit my job, so then my income was nothing.” Wealth measures, such as, home ownership, car ownership, and family savings acted as buffers to families' loss of income throughout their child's treatment. One low-income mother who did not own her home explains, “[my son] was getting Social Security Insurance, and I had just moved into government subsidized housing because I wasn't getting income.” Other families who had more wealth were able to stay in their homes, maintain their car ownership, or use savings to support periods of reduced income.

Financial help from friends and family: an important component of household finances

Another prominent finance-related theme that emerged from the interview transcripts was access to financial help from friends and family. Several parents reported receiving significant financial support from friends and family throughout their child's care. One high-income mother who owned a home in a wealthy neighborhood described, “People in this new neighborhood that we've never even met before were sending us checks… [My husband] came home one day with a tree, and on this tree they had tied gift certificates, gift cards for gas, for food…just hundreds and hundreds of dollars…he has [coworkers] that just randomly will give us a hundred bucks.” Another low-income family received help from family that allowed them to stay in their home after both parents lost their jobs,

[We asked my parents] for help paying for new tires. When we moved here, we still had our other house and we were trying to sell it, and the area we had bought in had experienced a real downslide with real estate, and…we ended up signing the house back to the bank. So we just walked away with nothing…And my parents said ‘well, just stay in the house and when you can afford it you can get a mortgage,’ and we still at this point don't have a mortgage but we're paying my mom rent to cover the expenses of the house, the taxes and the insurance and everything and she's counting that as down payment money.

This financial assistance received from friends and family helped some families maintain their other financial commitments while their income was highly volatile throughout their child's treatment.

Education Domain

Differences in communication between parents and health care professionals

Several themes emerged when the interview transcripts were separated by parental education level. One common theme was a link between parents' educational attainment and their perceptions of effective communication with medical professionals. One mother with a high school degree describes, “I started learning the hard way to start keeping more detailed notes on everything. I had been sort of encouraged not to…by doctors. They said ‘Oh you don't need to write everything down.’ And then other people…said ‘Take notes.’ And you kind of learn as you go…I started to learn to question things.” Parents with a high school degree or less often referenced this theme of learning by ‘trial and error’. Parents with a college degree or more often discussed being equipped to communicate effectively with physicians, and understand their child's diagnosis and treatment options. One mother with an M.B.A. explains,

Well, both my husband and I have the benefit of being science majors. He is…biochemistry, and I was biology…so the terminology and those things are not foreign to us. So, I will tell you, that going through this and meeting the people we meet…we are at a huge advantage, not to brag, but we're smart and we're educated and we know how to research this stuff and so it just, really when you're in our position, you have to do that. You can't put all your eggs in the doctor's basket and expect them…to just tell you what to do and you're gonna do what they say, you have to do your homework and you have to reach out to other places…I credit most of that to my husband though, he is extremely analytical and very organized and very detailed and very assertive without being aggressive, so he asks the tough questions.

A theme that emerged among parents with a high school degree or less was having difficulty reporting medical events that happened at home when health care professionals were collecting a medical history. These parents also reported having diffucalty understanding their child's diagnosis and treatment options. One mother with a GED describes,

I learned more from talking to parents and the nurses than I did from anybody else. The doctors they are like ‘this is what it is, do you have any questions?’ And as you have questions they give you the most generic answer there is…The nurses would say, ‘You might want to go with [this treatment option],’ but without saying why…And I guess I really wasn't listening…So that is something I have learned though all of this, to be a much better listener.

A reoccurring theme in interviews with parents with a high school degree or less was feeling more comfortable communicating with nurses and other parents than with physicians.

The role of social networks in health care navigation

Another theme that emerged from the data analysis was differences in the utility of families' social networks to help them navigate the medical community. All respondents with a college degree or more discussed having some person in their immediate social network who was in a position to help them access additional information, or connect with second opinions. One father with an MD explained, “We got good recommendations…My sister-in-law's fiancé is a pediatrician in [large city in the Northeast US]. He got me in touch with someone from [hospital in New York City] who said ‘By all means bring [your son] out, I will do a second work up on him.” Other high education parents discussed having connections to librarians, physicians, or university professors who helped them access and understand medical literature or connect with second opinions. Most parents with a high school degree or less did not discuss having these ties to the academic or medical community. These parents discussed getting their information “from other parents,” “nurses,” and internet sources, such as “web MD.”

Occupation Domain

Work schedule flexibility and access to other fringe benefits

The most common theme that emerged from analysis of the respondents' description of their occupation was the importance of work schedule flexibility for dictating parents' ability to manage their child's care. Parents discussed the role of their work schedule and flexibility in relation to scheduling appointments for doctors visits and medical procedures, being available to speak with doctors on the telephone, conducting medical research, and balancing work, their child's care, and their other parenting responsibilities. One mother who worked as a bank teller explained, “I had a full time job before [her] diagnosis. People at work were horrible. [They] said if they gave me time off they would have to do it for everyone.” The implications of work schedule flexibility impacted parents who had jobs that were categorized as both high SES occupations and low SES occupations, and this was a reoccurring theme in interviews with parents from both SES high and low SES groups. One mother explains,

The unfortunate part about my husband's situation is that he's a teacher, so unlike me, who I'm at my desk in front of a computer all day long with time to do this stuff, he doesn't have that time or that luxury. In fact, he is waiting for [a second opinion] to call him today at school and he is like ‘If they don't call me during one of my breaks I'm not going to be able to talk to them’ and [with my job] I can stop the presses and talk whenever I need to, but because he is the one that is sort of in the driver's seat with all this, I feel bad that…he is in that situation and he doesn't have the luxury to really have the time that he needs with those people.

Parents who had flexible work schedules discussed reduced burden associated with maintaining employment throughout their child's care. One mother who is in management at a technology firm describes her experience,

I was very lucky. I didn't work Fridays to begin with…which was worked out when I went on maternity leave with my first [child]…So these chemos that happened on Friday weren't taking me away from work…When [patient] started treatment I asked to have another day, to have one day to work from home…I would really be doing work from home but I would be getting other things done, the laundry, the grocery shopping, keeping up with things so that when the weekend came, we could have some quality family time together, and I wouldn't be cleaning the house or doing this or that…they didn't cut my pay to do that…if she had an MRI that [fell] on a Monday, when my day from home was Tuesday, I would just switch them…my job worked with me so that when I needed the time off I could take it, I was very rarely ever docked for anything related to [my daughter's] situation.

Within the interview transcripts and field notes, parents often referenced schedule related fringe benefits (work from home, paid time off, and flextime) in discussions of their ability to comply with their child's treatment protocols, balance work and their child's care, and the stress associated with maintaining other household responsibilities.

Access to employer sponsored health insurance

Parent's occupation determined their access to, and the benefits included in, employer-sponsored health insurance plans. Parents who did not have access to health insurance through their employer often spent a large amount of their time in the weeks after their child's diagnosis on public health insurance enrollment. One mother explains,

[My husband] was in a situation where he was going through periods of layoff with his employer, and we knew that it was only a matter of time and they were going to close. And at that point I had only been working part time, as soon as [my daughter] was diagnosed, I just quit working. So we were worried about finances, but they helped us apply for Child Health Plus and Family Health Plus when [my husband] actually lost his job and lost his insurance.

In addition to differences in access to employer-sponsored health insurance coverage, the quality of health insurance varied widely. One father who is a bank manager explains, “[Our] insurance covered everything. [We had] no co-pays, nothing like that.” Another mother who works in education describes the benefits her health insurance offers,

[Our insurance paid for] play therapy, music therapy…a social worker…they allowed us to reimburse our mileage to and from the hospital, parking…we went to see a counselor to help us manage the stress in our lives…we saw him twice a week but they reimbursed us to go see him. They reimbursed a babysitter for us…up to ten dollars an hour for up to six hours a week…they also paid for my husband and I to get a one hour massage every month…I think overall just felt like we've had very little out of pocket expense for what we've had to deal with.

Parents often referenced themes surrounding the quality of their health insurance when discussing the financial stress associated with their child's illness.

Discussion

Health related research often uses income or education as a proxy for SES. However, these findings suggest that a more nuanced conceptualization and measurement will enhance our understanding of how SES affects health care navigation, and help refine intervention initiatives designed to help reduce health disparities. Three major domains of SES were identified during data analysis, and seven themes emerged that link these SES domains to health care navigation. These findings show that income can be highly variable throughout cancer treatment. Due to this, it may be difficult to obtain an accurate approximation of respondents' income depending on when data is collected. Among the respondents in this sample, a very different financial picture would be painted if income data was collected at the point of diagnosis, during treatment, or after active treatment was complete. These findings also suggest that income alone does not provide a complete representation of families' economic means. Family wealth and help from friends and family reduced the financial strain associated with treatment and parental loss of income for some families. These finance related pathways are not captured by income measures on questionnaires. Future research that seeks to understand the relationship between finances, health seeking behavior, and health outcomes should include measures of wealth and access to financial help from friends and family in order to gain an accurate understanding of patients' financial means. These findings also suggest that the financial domain was the SES construct that was most sensitive to change after a cancer diagnosis. Due to this, future research should attempt to include measures that capture the volatile nature of patient's finances after a childhood cancer diagnosis.

Education is also a commonly used proxy for SES in health research. Due to changes in work status after their child's diagnosis, parents' educational attainment did not always correlate with their financial means. Due to this, future research should focus on identifying which aspects of SES is of empirical importance, such as access to finance-related resources, or the skills, knowledge, and status associated with levels of educational attainment, and make measurement decisions appropriately.

Characteristics of individuals' occupations are not commonly used in health related research, however these data suggest that they present important opportunities and barriers that may mold patients' patterns of health care navigation. The most common occupation-related theme that emerged in these findings was the role of work schedule flexibility. This obstacle to accessing the health care community was a characteristic discussed by parents with jobs defined as both high and low SES. Results reveal that work characteristics present important opportunities or barriers for patients, and should be included in research on health care navigation.

Strengths and Limitations

In this study, the qualitative findings present a nuanced and in-depth view of the ways that SES affects the health care experiences that is difficult to capture in quantitative research. However, several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting these findings. First, all respondents were recruited from one home care nursing agency and were patients at one of two hospitals in the same city in New York State. Therefore, their experiences may not represent the experiences of individuals who live in different parts of the country, who may have access to different types of health care assistance, or who receive their care in different health care settings. Also, due to the small sample size the generalizaiblity of the results cannot be assessed. Future research should examine these seven themes with a larger, more diverse sample.

Conclusions

This study sought to understand the processes through which individuals translate socioeconomic resources into health advantage, and the findings have implications for clinical practice and future research. This study underscores the need to use a nuanced set of SES measures in future research (beyond income and education) to enhance our understanding of the processes that contribute to disparate health outcomes.

This research highlights the complexities of health disparities, revealing that even when individuals of high and low SES have access to the same health care resources, they may use these resources in different ways. These different patterns of health care navigation may play an important role in the pathways that link SES and cancer outcomes. Many initiatives aimed at reducing socioeconomic health disparities focus on increasing access to care and access to health insurance. However, these families' experiences illustrate the need for interventions to be integrated into clinical practice to address issues beyond health care access.

Specifically, these findings have implications for enhancing patient-provider interactions. A theme among low SES parents was difficulty reporting medical history, communicating with physicians about their child's medical care, and understanding treatment protocols. High and low SES parents also used their time with health care professionals very differently. Interactions between high SES parents, nurses, and physicians were often dominated by discussion of their child's care and treatment strategies while low SES parents often spent their time with health care professionals discussing enrolling in public health insurance programs, resolving financial problems, or conflicts between their child's care and their other work and family commitments. These differences in patterns of communication may be an important process in the SES-health outcome link, and an opportunity for intervention initiatives aimed to reduce socioeconomic health disparities. Low SES parents may benefit from an advocate who helps to bridge the divide between parents and health care professionals. Several low SES parents discussed feeling more comfortable interacting with nurses than with their child's physicians. Due to this, cancer nurses may be particularly well positioned to serve in this role. Cancer nurses should have informal conversations with parents to teach them how to effectively communicate about their child's care.

Intervention initiatives aimed at educating clinicians about these different styles of communication, and strategies to effectively communicate with parents of diverse education, literacy, and self-expression skill levels may be another strategy to translate findings into clinical practice. Cancer survivorship has gained significant attention in recent years, and many institutions have begun to offer increased support services to their patients from the point of diagnosis on. These survivorship-oriented programs may be an ideal forum for integrating material on effective health communication, resources and information available to cancer patients, and strategies to overcome financial and work-related obstacles to cancer care. Alternatively, a standard social work assessment should include questions about patient's ability to effectively communicate with their physicians, access the information they need, balance work and their cancer care, and their concerns about finances. Asking patients these questions would enhance clinicians' abilities to tailor treatment protocols to individual patient needs, and contribute to the development of educational materials and programs aimed to reduce SES cancer disparities. Future areas for research include examining patterns of health care navigation with an ethnically and racially diverse sample and targeted intervention studies designed to help both clinicians and patients overcome SES-based barriers to quality care.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Farrell, Debra Street, Robert Wagmiller, Martin Brecher, Michael Zevon, Deborah Erwin, Jean Ford and the anonymous reviewers for their extensive and helpful feedback throughout this project.

Grant Support: The Mark Diamond Research Grant, the University at Buffalo, supported this research and the National Institute of Health grant number R25CA114101.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The author has no financial disclosures to report.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chu KC, Miller BA, Springfield SA. Measures of racial/ethnic health disparities in cancer mortality rates and the influence of socioeconomic status. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;10:1092–1104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linabery AM, Ross JA. Childhood and adolescent cancer survival in the US by race and ethnicity for the diagnostic period 1975-1999. Cancer. 2008;113:2575–2596. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompshon TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113:2910–2918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang M, Burau KD, Fang S, Wang H, Du XL. Ethnic Variations in Diagnosis, Treatment, socioeconomic status, and survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2008;113:3231–3241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawley OW, Berger MZ. Cancer and disparities in health: perspectives on health statistics and research questions. Cancer. 2008;7S:1744–1754. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Ann Rev Pub Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brookfield KF, Cheung MC, Lucci J, Fleming LE, Koniaris LG. Disparities in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: a problem of access to care. Cancer. 2009;115:166–178. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer. 2008;113:582–591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alder NE, Ostrove JE. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don't. Annals N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutfey K, Freese J. Toward some fundamentals of fundamental causality: socioeconomic status and health in the routine clinic visit for diabetes. Am J Soc. 2005;110:1326–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG, Phelan JC. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, Gantz ML. Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: on the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Quart. 1998;76:375–402. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. Fundamental causes of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya C, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Press; Thousand Oaks, Calif: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Sage Press; Thousand Oaks, Calif: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative Research Methodologies: ethnography. BMJ. 2008;337:a1020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitzman EA, Miles MB. Computer Programs for Qualitative Data Analysis: A Software Sourcebook. Sage Press; Thousand Oaks, Calif: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lareau A. Invisible inequality: social class and childrearing in black families and white families. Am Soc Rev. 2002;67:747–776. [Google Scholar]