Abstract

PURPOSE Numerous primary care practice development efforts, many related to the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), are emerging across the United States with few guides available to inform them. This article presents a relationship-centered practice development approach to understand practice and to aid in fostering practice development to advance key attributes of primary care that include access to first-contact care, comprehensive care, coordination of care, and a personal relationship over time.

METHODS Informed by complexity theory and relational theories of organizational learning, we built on discoveries from the American Academy of Family Physicians’ National Demonstration Project (NDP) and 15 years of research to understand and improve primary care practice.

RESULTS Primary care practices can fruitfully be understood as complex adaptive systems consisting of a core (a practice’s key resources, organizational structure, and functional processes), adaptive reserve (practice features that enhance resilience, such as relationships), and attentiveness to the local environment. The effectiveness of these attributes represents the practice’s internal capability. With adequate motivation, healthy, thriving practices advance along a pathway of slow, continuous developmental change with occasional rapid periods of transformation as they evolve better fits with their environment. Practice development is enhanced through systematically using strategies that involve setting direction and boundaries, implementing sensing systems, focusing on creative tensions, and fostering learning conversations.

CONCLUSIONS Successful practice development begins with changes that strengthen practices’ core, build adaptive reserve, and expand attentiveness to the local environment. Development progresses toward transformation through enhancing primary care attributes.

Keywords: Patient-centered medical home, National Demonstration Project, quality improvement, primary care, relationship centered, complexity theory, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

For more than a century, small, physician-led medical practices were the most common source of primary care throughout the western world.1 The future viability of this cottage industry is now in doubt, and primary care in the United States and elsewhere is seriously weakening.2 Hopeful energy for changing and transforming primary care practices arises from this deteriorating situation.3 Practice development activities are emerging as part of state initiatives, Medicare pilot programs, health system projects, and independent innovations.4–6 The difficulties and resistances challenging this hard work are daunting, with few research-informed approaches available to help guide these critically important initiatives.7–10 In this article, we offer a theory-based, evidence-informed relationship-centered approach for primary care practice development derived from 15 years of research on primary care practice improvement11 and, most recently, from the American Academy of Family Physicians’ National Demonstration Project (NDP). The NDP represents one of the first research trials seeking to implement and assess an intensive whole-system redesign of primary care practice based on the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) construct within independent family medicine practices.

The evaluation of the NDP provides new windows of understanding into the practice change and transformation process.12,13 The relationship-centered practice development approach presented here emerged from our cross-cutting interpretation of the findings from this evaluation. The resulting insights are associated particularly with 6 features of the NDP: (1) exceptionally high motivation for major development; (2) emphasis on whole-practice redesign; (3) intense telescoping of the development process because of the limited 2-year time span; (4) comparison of external facilitation with self-direction; (5) measurement of both patient experience and clinical care; and (6) emergence of transformational development.

The first part of this article starts with a brief overview of the attributes of primary care that enhance value and represent the goals of practice development. We describe several concepts and models for understanding practice development using a relational theory of organizational learning that is based on complexity science. We briefly summarize core concepts and principles from these theories, with references for those who want more detail. We begin building our approach with a model of practice features related to practice development and then expand to a more comprehensive model for understanding change and development. This section ends with a description of the natural history of practice development, both change and transformation, based on evidence from the NDP.14 The second part of the article combines theory, models, and experience from the NDP, and suggests a way for using this relationship-centered practice development approach to plan and implement practice improvement.

UNDERSTANDING PRIMARY CARE PRACTICES WITH INTENT TO ENHANCE VALUE

Value of Primary Care

Health care systems that emphasize and support vigorous primary care have better population health, lower costs, higher quality, and less inequity than other systems.15 This enhanced value emerges from synergy among the following 4 functional attributes:

Easily accessible first contact with the health care system

Comprehensive care for all health-related situations regardless of age or sex

Coordination and integration of care across settings

Personal relationships over time through partnerships in the context of family and community

A major reason for the declining value of health care in the United States relative to other industrialized nations is the serious erosion in the ability of primary care to fulfill these functions.16 Theory supporting primary care and several mechanisms explaining how these attributes create primary care’s value are well defined.17,18 A fundamental principle of primary health care is to focus on improving the health and relationships of the whole person in his or her life context rather than just managing disease.19,20 The decline in the patient-rated measures of the primary care functions seen in the NDP21,22 may relate to the NDP’s emphasis on implementing technological components instead of primary care attributes.13 We therefore suggest the goals for primary care practice development are to optimally enact these 4 attributes of primary care, improve the health of whole people, and foster healing relationships.

A Relationship-Centered Approach: Theoretical Foundations

A primary care practice consists of the people and places (ie, relationships) where the primary care functions are enacted in pursuit of better health. Our approach to primary care practice development, based on the NDP experiences,14 highlights the importance of relationships. Health as relationship20 is a development goal and is facilitated by healing clinician-patient relationships.23–25 Successful, sustained practice development requires strengthening of both internal relationships within the practice and external relationships with the local community and patients. Conversation is a core tool for development work. We therefore refer to our practice development approach as relationship centered, paralleling the relationship-centered style in clinical care.26–28 This is an approach to the dynamic process of intentional practice development and not an approach for determining quality assessment or better delivery options. Donabedian’s structure, process, and outcome model remains an excellent background framework for this important quality work.29,30 A relationship-centered practice development approach helps make sense of why some practices improve, respond to external and internal changes, and even transform, while others doggedly resist change.

Complexity theory provides a helpful lens for understanding how practices behave over time within their environmental contexts.31–34 From this perspective, primary care practices are complex adaptive systems, and thriving ones are often like an excellent improvisational jazz band.35 Adaptation is the successful ability both to respond to changes in the local environment as well as to intentionally create change in that environment. Self-determination theory36 and its associated relational theory of organizational learning suggest approaches for influencing and shaping the behavior of complex adaptive systems through the identification of emergent patterns of meaning and relating and the strategic use of conversations.27,37 (Please see the Supplemental Appendix at http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/8/suppl_1/s68/DC1 for more details about complexity theory.) Several important principles for influencing practice development ensue from understanding primary care practices as complex adaptive systems. It is valuable to recognize and pay attention to the following when engaged in practice development work:

Cause and effect are rarely simple, direct, or linear.

Any action or decision has multiple consequences that change the environment and influence the actions and decisions of others.

Many consequences are delayed in time and not predictable or immediately knowable.

Novelty, surprise, and unintended consequences are expected.

Purposeful change and development seek improvement, not perfection, and require ongoing reciprocating feedback and learning.

Improvement and development are emergent and arise from competing demands and opportunities.

Variety, diversity, and conflict need to be anticipated and used as important sources of new information and learning.

Maximal efficiency is potentially harmful to practices as it eliminates some necessary redundancy and spare capacity for adaptation.

A Practice-Level Model for Understanding Practice Development

Primary care practices, as complex adaptive systems and as described in the NDP,13,14,21,22 are conceptualized as having a core, an adaptive reserve, and an attentiveness to the local environment. These features are outlined in part in Table 1▶ and described below.

Table 1.

Elements of Practice Core and Adaptive Reserve

| Feature | Element |

|---|---|

| Core | |

| Resources | Material |

| Human | |

| Organizational structure | Leadership, compensation, reward, and accountability systems |

| Management model | |

| Functional processes | Clinical care |

| Operations | |

| Finance | |

| Adaptive reserve | Action and reflection cycles |

| Facilitative leadership | |

| Learning culture | |

| Improvisational ability | |

| Stories of change | |

| Sensemaking | |

| Relationships and communication | |

Core

The core consists of resources, organizational structure, and functional processes. The resources fall into 2 categories: material and human. Material resources include money, facilities, and space, including workplace design, equipment, and technology infrastructure (eg, computers, Internet access, telemedicine). Human resources include the number of personnel and their skills.

The organizational structure (ie, leadership, compensation, reward, and accountability systems) is guided by a management model (eg, organizational chart, decision allocation). The dominant management model in primary care practice from the 19th century into the early 1980s was a simple “front” and “back” framework separating the business and clinical aspects of practice.38 This dual hierarchy placed the autonomous physician leader as the ultimate authority. The rapid growth of larger group and system-owned practices, beginning in the 1970s and modeled on industrial organizational design, recreated the dual hierarchy as a dual organization with a stronger practice manager role.39 In the United States, managed care and the subsequent consolidation of health care organizations accelerated this trend over the last 2 decades. Converting this dual structure into an aligned management model is essential for effective practice development.14

We differentiate 3 functional processes or internal models of the practice core. Clinical care includes both care processes and protocols in the practice, and clinical methods and styles (eg, biomedical, patient centered).40,41 Practices also have operations processes related to supplies, support, staffing, measurement, and information distribution. Finally, they have finance processes concerned with the practice business model (eg, direct practice, traditional insurance, management fees, supplemental services) including budgeting and the revenue cycle.

The adequacy of a practice’s core is a measure of its robustness, where robustness is the ability to maintain a given state under force or in differing conditions.42 A robust primary care practice is one wherein resources, management model, and functional processes are adequate to meet ordinary variations in economic conditions, community expectations, and regulatory requirements. A strong core ensures that a practice maintains a consistent performance, the ability to deliver reliable primary care, despite common fluctuations in external conditions. Figure 1▶ depicts a model of the practice core.

Figure 1.

Relationship-centered practice core model.

Adaptive Reserve

Even the most robust trees are blown over by extraordinary winds unless they are also resilient or able to bend under force.43 We are in such turbulent times3 and, as we observed in the NDP,21 a strong practice core is not adequate for the needed responses. We name those features in primary care practice that enhance resilience the adaptive reserve. The adaptive reserve is often in the background, as if in reserve, during stable times; however, during times of dramatic change, it facilitates adaptation and development. The features of adaptive reserve include action and reflection cycles in the practice,44 facilitative leadership,45 a learning culture,46 the ability to improvise,47 a repository of helpful stories about change in the practice,48 and effective relationships and communication.49 Sensemaking,50 teamwork, and a more positive work environment are emergent properties that arise when the adaptive reserve features are present and operating well. Figure 2▶ depicts a model of the practice adaptive reserve, including elucidation of the 7 relationship characteristics that are particularly important for practice resilience.49

Figure 2.

Relationship-centered practice adaptive reserve model.

Relationship Characteristics

Mindfulness = Openness to new ideas and different perspectives; continuous creation of new categories.

Respectful Interaction = Honest, tactful, and mutually valuing interchange where each person brings meaning and value to the other.

Heedful Interrelating = Interaction where individuals are especially sensitive to the way their role and others fit into the larger group and its goals.

Channel Effectiveness = Appropriate use and mix of rich (eg, face-to-face) and lean (eg, e-mail) communications where rich channels are used when messages are highly ambiguous, complicated, or emotionally charged and lean channels are used when messages are clear, simple, and emotionally neutral.

Mix of Social and Task Relatedness = Social relatedness includes non–work-related conversations and activities that are often based on friendships and family, whereas task relatedness consists of work-related conversations and activities.

Diversity = Differences in mental models and in age, sex, and ethnicity.

Trust = Belief that you can depend on the other and the associated willingness to be vulnerable to another.

Attentiveness to the Local Environment

The practice characteristic that consistently differentiated the most resilient practices in the NDP was attentiveness to the local environment. Resilient practices in the NDP were engaged with their local hospital systems, local employers, several community agencies, and public events.14 The staff and practitioners often lived near their practices and were deeply connected to the community. News of what was happening was openly shared, and opportunities for how to influence or respond to local conditions, or both, were often explored. All of these external relationships were sources for learning and developing in these practices.

A primary care practice’s core, adaptive reserve, and attentiveness to the local environment represent the practice’s internal capability. An effective core is a necessity for every primary care practice. Building effective adaptive reserve is also essential during times of dramatic change or when undertaking major practice redesign, as was the case in the NDP.14,21 Given the current beleaguered status of primary care and the need for substantial improvement if primary care practices are to successfully implement their goals, now is an important time to work on improving adaptive reserve features.

A Comprehensive Model for Practice Development

Primary care practices, like many organizations, demonstrate remarkable resistance to improvement efforts even when they have adequate internal capability.51,52 The Practice Change and Development (PCD) model, illustrated in Figure 3▶, identifies 4 interacting domains that describe how development evolves over time.53 The upper half (boxes 1 and 2) of this figure represents the practice. Box 2 (upper right) is the practice’s internal capability—the core, adaptive reserve, and attentiveness to the local environment. Box 1 (upper left) signifies the motivational forces or available energy within the practice for whatever change or developmental improvement is intended. In our past research53–58 and in the NDP,14,21 sustainable practice improvement required the motivational support and engagement of formal leadership, both physician and management, and any informal leaders among other clinicians and staff.

Figure 3.

Practice Change and Development model.

The lower boxes in Figure 3▶ represent the practice’s external environment. Box 3 (lower left) consists of outside motivators for desired improvements or developments. These motivators include supportive health policy, facilitators or consultants, patient input, or a health system. Box 4 (lower right) refers to available options for change and improvement. The arrows in the figure signify the interactions among the 4 boxes that shape the success or failure of the particular development efforts over time and represent the opportunities for relational learning. The PCD model suggests that thriving and ongoing, adaptive practice development optimizes internal and external motivation, enhances internal capability, expands awareness of options, and ensures ongoing interaction across these areas.

Complexity theory and the PCD model suggest that resistance to change occurs when planned interventions do not fit with the internal models and simple rules of a self-organized complex adaptive system. Resistance usually means the desired intervention makes little sense relative to major aspects of the existing system. Overcoming that resistance requires motivated engagement of the leadership team and change in multiple parts of the core at the same time, so that these areas (eg, work-place design, information distribution, measurement, and reward systems) reinforce the intended behavior change.59,60 The 5 case summaries in the qualitative report on the NDP all depict these processes.14 Gathering external support may also be necessary.

A Natural History of Practice Development

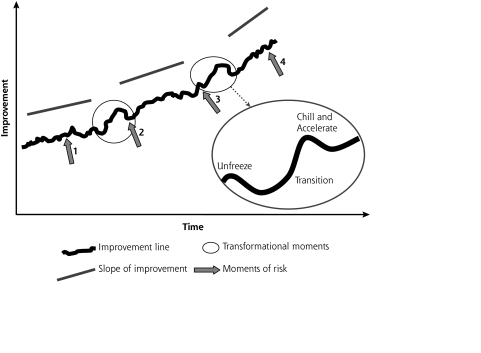

The qualitative analysis of the NDP data revealed multiple pathways for change and possible transformation. Figure 4▶ illustrates a composite optimal pathway based on the courses of improvement shown by the more successful practices in the NDP.14

Figure 4.

Developmental pathway of change and transformation.

The jagged upward-trending line represents the everyday, ongoing work of continuous improvement in a robust practice that values learning. The jaggedness, like a fetal heart tracing, represents healthy beat-to-beat (day-to-day, week-to-week) variability. The NDP practice e-mail streams illustrated this weekly unevenness whereby, on any given day, an e-mail characterized things as getting a little worse, but then described improvement several days later. This is the change of effective continuous improvement activities. None of these changes, by themselves, alters the fundamental patterns of meaning and relating in the practice. Practice development is often slow and barely detectable. But it also occurs in sudden bursts.

The 2 circles on the irregular line in Figure 4▶ mark discontinuities along the pathway. These are moments of more dramatic transformation in which the underlying assumptions of the practice change.61 For example, Practice B in the NDP14 was slowly improving, working on small changes in its adaptive reserve, until the realization of real teamwork and role changes emerged near the end of the study and dramatic transformation began. After such episodes, the slope of improvement increases as depicted by the straight lines above the jagged one. This is a practice that recognizes opportunities for whole-practice redesign. We borrow Kurt Lewin’s simple 3-stage model for describing transformation—Unfreeze, Transition, and Refreeze62—but reframe the last stage and call it Chill and Accelerate. In a practice that is continually learning and improving, the idea of refreezing is too static. As shown in the NDP, it is important to chill or slow down after a major transformation and assess all of the many repercussions before accelerating development.63

The 4 arrows in Figure 4▶ point to areas of high risk, where the pathway of development could flatten and even decline with inadequate attention. Arrow 1 can be anywhere along the line except at transformation moments. It points to the daily, disciplined work of continuous improvement of the practice core, which also includes preparing for the catalytic opportunities for transformation by enhancing adaptive reserve. Without consciously making time for reflection and sensemaking, it is easy to get sleepy and sloppy when caught up in doing the often hectic work of primary care. Arrow 2 directs our attention to the end of transformational work and the risk of refreezing. It is important to address the many new issues that emerge with transformation, but not to let the challenges stop the overall pathway of continual development. Arrow 3 points to the initiation point of transformation, where a risk is to miss it or not generate the necessary motivation and negotiate acceptance from critical colleagues. Such missed opportunity was a key factor in why a few practices in the NDP made less change than most others. The high risk of change fatigue63 is indicated by arrow 4. Such high risk is especially common in practices that have experienced several redesign efforts as well as ongoing development.

PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTING PRIMARY CARE PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT

This section outlines an approach to planning and implementing primary care practice development. It is not about project management or how to implement a specific performance improvement such as promoting guideline adherence or increasing preventive services screening. It is about ongoing whole-practice redesign that may include individual projects but really emphasizes development and coevolution with larger systems, patients, and communities in pursuit of better enactment of the core primary care functions. This approach is grounded in what we observed in the more successful NDP practice development efforts.14 We purposefully refer to the approach as primary care practice development to accentuate its longitudinal aspect and the inclusion of both change and transformation as goals (Figure 4▶). This overall development approach consists of the following 4 strategies:

Setting direction and boundaries

Implementing sensing or feedback systems

Focusing on creative tensions or important differences in feedback

Fostering multiple conversations to promote learning

These strategies are simultaneous and not sequential.64 They all require understanding the role of conversation and sensemaking in practice development and interventions.65,66

Complexity theory reminds us that all interventions have both planned and unexpected aspects.67,68 An intervention involves the development content as well as the tactics for implementation. Relational theory of organizational learning reminds us that enacting the intervention requires the giving of instructions and the exchange of information. These are planned activities, but we know that unanticipated surprises and resistances emerge during any intervention.54 We consider conversation to be a critical collaborative process for mediating the planned and the unforeseen. Like the music of an improvisational jazz group, the conversation itself is spontaneous and unplanned, but the staging of who and where and agenda can be deliberate. It is within conversations that meaning and sense are cocreated and learned.

Setting Direction and Boundaries

Setting direction and boundaries is the design phase.69 Practice vision and mission are foundational aspects of setting direction and answer the questions, Why are we here as a practice? and What makes us important and meaningful? These questions tap into personal sources of meaning for practice members that are vital for motivating development.25 In the NDP, that vision included becoming a PCMH. Facilitated practices often focused on implementing the NDP model’s PCMH components and demonstrated great improvement in that area, whereas many self-directed practices maintained their emphasis on the patient and a few were better able to maintain the patient-rated measure of PCMH.22 The setting of direction involves specifying the boundaries of action, clarifying roles and expectations, and identifying where attention is directed, what is meaningful and important. As noted earlier, we believe the functional attributes of primary care and health are the heart of the matter.70 Practice vision needs to motivate key practice personnel. The following are some guidelines and examples of related questions for successful direction setting:

Clarify priorities: Whose needs come first, patient or physician? Is the electronic medical record (EMR) more for billing or clinical information?

Generate a sense of urgency: Why is this so important? What must be done to meet this deadline?

Distribute leadership and control: How can I help? What do we need?

Build vision into the budget: Does the money match the purpose?

Build vision into the schedule: Does the use of time match what is important?

Take a developmental perspective: What relationships do we need to develop now to be more effective over time?

Setting direction in complex adaptive systems is an open and ongoing process. There is no final destination other than optimal implementation of the primary care functions.

One of the important tasks in boundary setting is to establish the range of variation that fosters development in the desired direction. This boundary work applies to all parts of practice life. What are the minimum and maximum number of hours of work per day or week that enable optimal performance for clinicians and staff? What are the upper and lower limits of number of patients seen per hour that ensure optimal care? What high or low blood pressure levels should activate special attention? What low revenue number should trigger corrective action, and what high revenue number should initiate exploration of how the practice might care for more underinsured? These are typical questions in boundary setting. Maintaining the boundaries requires ongoing assessment and feedback.

Implementing Sensing Systems

A practice’s resilience is tightly coupled with its ability to learn and use that learning to adjust. Optimal learning by a practice requires feedback about itself and its environment. That feedback depends on having suitable sensing systems in place. Feedback is in the form of stories, metrics, visuals, interviews, observations, records, and surveys. The purposes of feedback are to let a practice know how well it is doing given the direction and boundaries set and what is happening in the environment related to direction and boundaries. Sensing systems also alert a practice when it is getting outside its desired boundaries.

An example of a sensing system is an assessment of finances at least monthly and the other core features twice a year. Yearly review is probably adequate for monitoring adaptive reserve, motivation, and outcomes. It is also important to regularly collect and share stories and information about what is happening in the community, local health systems, and larger policy landscape. This is a great way in which to invite patients into the process. Every practice must adjust their sensing to what is more helpful and feasible for them. Holding regular meetings and collecting and reviewing all of these measures may initially seem overwhelming to many already beleaguered US clinicians, especially in the private practice world. Our past research50,71–73 and the NDP experience14 convince us that dedicating this time and discipline both is possible and more than compensates for the extra time. Monitoring personal health and development is also important, especially during times of transformation or times at which there is a high risk of change fatigue.

Focusing on Creative Tensions

“Celebrate the abundance within troubles” was a mantra for thriving primary care practices in the NDP.13,14 When energized by vision, practices celebrated often and had faith in their ability to enact the vision. These practices got excited when their sensing systems indicated trouble because that identified areas of emerging opportunities for development and creativity. Examples of such trouble included problems with access to well-child care, communication breakdowns, staff distress, documentation concerns, inadequate diabetes care, an influenza pandemic, physician resistance to team care, and declining revenues. These were creative tensions, touch points for practice development.

A strong adaptive reserve greatly assists this work of focusing on creative tensions.21,63 The current situation—in which most practices have a dual hierarchy management model, an authoritative leadership style, an absence of psychological safety, few meetings, limited diversity of ideas, and suppression of difficult issues and emotions—impedes the learning, good sensemaking, and improvisation necessary for successful and sustainable improvement. The following are some guidelines and examples of related questions for focusing on creative tensions:

Encourage diversity: Who else needs to be here?

Explore contradictions: How else might we think of this? Why are we doing this when we want to do that?

Hunt for troubles in the environment: What is happening in the community (or local health system) that can help us? What innovations are out there?

Think about power laws: Where is the 20% of effort that accounts for 80% of output?

Look for ripples: How does that new scheduling process affect charting?

Fostering Learning Conversations

Setting direction and boundaries, implementing sensing systems, focusing on creative tensions, and implementing the many interventions that emerge are all activities that rely on the effectiveness of fostering learning conversations. Conversations generate motivation and power the building of capability. The genius of conversations is that they are constructible and spontaneous, formal and informal.65,74 An aligned management model, facilitative leadership, effective work space, good teamwork, strong relationship characteristics, feelings of safety, time for reflection, and high motivation all help to ensure appropriate spontaneous and informal conversations. This section focuses on the planning and creation of formal conversations. The arrows of the PCD model (Figure 3▶) represent the cross-cutting work of the many different coevolving conversations. Table 2▶ summarizes a typology of formal conversations.75–84

Table 2.

Typology of Practice Development Conversations

| Type of Conversation | Examples |

|---|---|

| Project | Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles |

| Project management | |

| Capability building | |

| Skill building | Learning collaborative workshops |

| Coaching | |

| System building | Reflection-action process (RAP) teams75 |

| Appreciative inquiry76,77 | |

| Dialogue78 | |

| Fireproofing | Crucial conversations79 |

| Mindfulness meditation80 | |

| Whole system | |

| Possibility | World Café81 |

| Future Search82 | |

| Action | Kaizen events83 |

| Open Space84 | |

Project Conversations

Project conversations relate to specific interventions currently under way in a practice. These conversations can be about large projects such as putting into operation an EMR or an open-access scheduling system, or implementing smaller ones such as a diabetes disease registry or practice Web site. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles and project management are especially useful for organizing these conversations if they are preceded by discussions that tie in to personal sources of meaning for what the PDSA cycles should be about.76

Capability-Building Conversations

Capability-building conversations focus on improving the effectiveness of the practice core, multiple domains of the adaptive reserve, and attentiveness to the local environment. Some of these conversations spotlight specific instrumental skills, such as leadership development, budgeting, EMR use, and patient self-management tools. These are skill-building conversations that involve the use of learning collaboratives with other practices or specific coaching from an outside source.

System-building conversations accentuate the process skills that facilitate the health of the practice as a complex adaptive system. These conversations are usually related to building the adaptive reserve and include reflection, relationships, communication, and conflict management. The creation of reflection-action process (RAP) teams,75 the use of dialogue as a communication strategy,78 and appreciative inquiry77 are all examples of system-building conversations.

The emotional challenges of change and change fatigue are a few of the reasons for also facilitating what we call fireproofing conversations.85 These conversations assist practice members in learning how to manage stress, engage in difficult conversations, and recognize signs of strain. Mindfulness meditation80,86 and the tools of crucial conversation79 are examples.

Whole-System Conversations

Because of the importance of matching motivations, vision, and relationships to how time is spent, it is useful for primary care practices to periodically stage whole-system conversations.10,87 These conversations offer an opportunity for everyone in the practice and even its key health care system stakeholders, patients, and community partners to check in, review the current direction and boundaries, and imagine what else is possible.88 Examples of conversational formats include World Café81 and Future Search,82 both highly successful conversational strategies for stimulating imagination and focusing collective vision.

Action conversations put emphasis on helping whole systems connect different aspects of practice in better ways to get the work done. Kaizen events83 and Open Space84 are both potent examples. One action conversation that is ready for everyday use and was a powerful development force in the NDP is the huddle.89 This 5- to 15-minute conversation at the start of a clinical session generates action plans for that day and provides opportunity for practicing and reinforcing the many learned skills from other conversations.

Sequence of Activities

The 4 strategies just presented are not sequential, but the relationship-centered approach to practice development does imply a particular sequence of activities for deploying the strategies. Begin with strengthening the core. This step includes improving documentation and coding (in the United States); systemizing the clinical record; enhancing the management model; developing care protocols, financial systems, and operations’ policies; and creating an information system plan. Then build the adaptive reserve by establishing regular meetings and action and reflection cycles wherein specific metrics and reports are reviewed. The third step is to actively explore the local environment for opportunity to better achieve primary care’s key attributes. Check out local health care systems, retail clinics, community agencies, and specialist connections. These first 3 steps ensure a strong foundation for taking the next, potentially more transforming step of dramatically enhancing the primary care attributes. Consider hiring more staff for care coordination and unloading clinician work. Improve and expand access. Implement an EMR, Web portal, and health system linkages, and begin true population health activities.90

CONCLUSION

Health care in the United States of America is broken.91 The primary care functions that are a foundation for repairing the system are devalued and collapsing.92 Yet, hopeful examples of primary care excellence send flickers of light from many small places across our vast fragmented health care geography. In the NDP, we witnessed both small rural primary care practices and large urban and suburban group practices making changes toward better serving the primary care functions. It is important, but not enough. Many of the necessary developments for achieving effective primary care will not be possible in the United States without substantial reform of the delivery system. We have provided an approach only for practice-level work. Health policy must also change.93

Primary care practice is presently and problematically conceptualized as the people and places where disease management, customer service, and productivity are optimized to deliver commodities of health care.94 Many are surprised that this approach is not working. We propose that a primary care practice consists of the people and places (relationships) where the primary care functions of access to first-contact care, comprehensive care, coordination of care, and personal relationship over time are optimized. It is where best available evidence is contextualized within coevolving and emergent healing relationships and applied to an identified population, community, or both.23 Better primary care practices are local, robust, and resilient teams of agents who coevolve, interdependently, with their local environments, learn from their mistakes, change their assumptions when necessary, and work with patients pragmatically, using appropriate science and knowledge to care for the health of their patients, their communities, and the population. What emerges from this healing landscape is better health at lower cost with greater equity.95 The relationship-centered practice development approach shows a way.

Acknowledgments

The NDP was designed and implemented by TransforMED, LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AAFP. We are indebted to the participants in the NPD and to TransforMED for their tireless work. We are deeply thankful for the extraordinary qualitative data support by Elizabeth Stewart. For important intellectual nourishment over the past decade, we are grateful to Reuben McDaniel, Jr, Holly Lanham, and Brian Stello.

Conflict of interest: The authors’ funding partially supports their time devoted to the evaluation, but they have no financial stake in the outcome. The authors’ agreement with the funders gives them complete independence in conducting the evaluation and allows them to publish the findings without prior review by the funders. The authors have full access to and control of study data. The funders had no role in writing or submitting the manuscript.

Disclaimer: Drs Stange and Nutting, who are editors of the Annals, were not involved in the editorial evaluation of or decision to publish this article.

Funding support: The independent evaluation of the National Demonstration Project (NDP) practices was supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and The Commonwealth Fund. The Commonwealth Fund is a national, private foundation based in New York City that supports independent research on health care issues and makes grants to improve health care practice and policy.

Publication of the journal supplement is supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Foundation, the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation, and The Commonwealth Fund.

Dr Stange’s time was supported in part by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society.

Disclaimer: The views presented here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers, or staff.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meads G. Primary Care in the Twenty-first Century. Seattle, WA: Radcliffe; 2006.

- 2.Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(9):861–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stange KC, Ferrer RL, Miller WL. Making sense of health care transformation as adaptive-renewal cycles. Ann Fam Med. 2010;7(6): 484–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;30 1(19):2038–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. http://www.pcpcc.net/node/14. Accessed Jun 13, 2009.

- 6.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. 2009 PCPCC Pilot Guide. http://pcpcc.net/pilot-guide. Accessed Oct 30, 2009.

- 7.Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Evidence-based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(1):138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidorov JE. The patient-centered medical home for chronic illness: is it ready for prime time? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;27(5):1231–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas P, McDonnell J, McCulloch J, While A, Bosanquet N, Ferlie E. Increasing capacity for innovation in large bureaucratic primary care organizations: a whole system participatory action research project. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):312–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas P. Integrating Primary Care: Leading, Managing, Facilitating. Oxford, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing, Ltd; 2006.

- 11.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15 year developmental program of research. Med Care. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.TransforMED. National Demonstration Project. http://www.transformed.com/ndp.cfm. Accessed Jun 13, 2009.

- 13.Stewart EE, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stange KC, Miller WL, Jaén CR. Implementing the patient-centered medical home: observation and description of the National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):s21–s32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Journey to the patient-centered medical home: a qualitative analysis of the experiences of practices in the National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):s45–s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starfield B, Shi LY, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandy LG, Bodenheimer T, Pawlson LG, Starfield B. The political economy of U.S. primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4): 1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- 18.Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- 19.Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine M, Peters JW. The Nature of Health: How America Lost, and Can Regain a Basic Human Value. Oxford, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical Publishing; 2007.

- 21.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1): s33–s44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):s57–s67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Miller WL, Stange KC, Crabtree BF. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egnew TR. The meaning of healing: transcending suffering. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egnew TR. Suffering, meaning, and healing: challenges of contemporary medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):170–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tresolini CP, Pew-Fetzer Task Force on Psychosocial Education. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care: Report of the Pew-Fetzer Task Force on Advancing Psychosocial Education. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Commission; 1994.

- 27.Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care: complex responsive processes of relating. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S40–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safran DG, Miller WL, Beckman H. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care: theory, evidence, and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S9–S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1996. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tollen L. Physician Organization in Relation to Quality and Efficiency of Care: A Synthesis of Recent Literature. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2008. Publication 1121.

- 31.Plsek PE, Lindberg C, Zimmerman B. Edgeware: Insights from Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders. Irving, CA: VHA; 1998.

- 32.Sweeney K, Griffiths F. Complexity and Healthcare: An Introduction. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002.

- 33.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel RR Jr, Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benner A. Organizational Survival in the New World: The Intelligent Complex Adaptive System. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2004.

- 35.Miller WL, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, Stange KC. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):872–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stacey R. Complex Responsive Process in Organizations: Learning and Knowledge Creation. London, England: Routledge; 2001.

- 38.Stein HF. The money taboo in American medicine. Med Anthropol. 1983;7(4):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crabtree BF, McDaniel RR, Nutting PA, Lanham HJ, Looney JA, Miller WL. Closing the physician-staff divide: a step toward creating the medical home. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15(4):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart M, Weston WW, Brown JB, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995.

- 41.Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Relationships between physician practice style, patient satisfaction, and attributes of primary care. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(10):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Read DW. Some observations on resilience and robustness in human systems. Cybern Syst. 2005;36(8):773–802. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamel G, Välikangas L. The quest for resilience. Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81(9):52–63, 131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weick K. Making Sense of the Organization. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers, Ltd; 2001.

- 45.Wilson PH. The Facilitative Way: Leadership That Makes a Difference. Shawnee Mission, KS: Team Tech, Inc; 2003.

- 46.Senge P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday; 1990.

- 47.Barrett F. Creativity and improvisation in jazz and organizations: implications for organizational learning. In: Kamoche KN, Cunha MPE, eds. Organizational Improvisation. London, England: Routledge; 1998.

- 48.Brown JS, Denning S, Groh K, Prusak L. Storytelling in Organizations: Why Storytelling Is Transforming 21st Century Organizations and Management. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005.

- 49.Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. How improving practice relationships among clinicians and nonclinicians can improve quality in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(9):457–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weick K. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995.

- 51.Greco PJ, Eisenberg JM. Changing physicians’ practices. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1271–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Attwood M, Pedler M, Pritchard S, Wilkinson D. Leading Change: A Guide to Whole Systems Working. Bristol, United Kingdom: The Policy Press; 2003.

- 53.Cohen D, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49(3):155–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruhe MC, Weyer SM, Zronek S, Wilkinson A, Wilkinson PS, Stange KC. Facilitating practice change: lessons from the STEP-UP clinical trial. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC. Understanding practice from the ground up. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):881–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crabtree BF, McDaniel RR, Nutting PA, Lanham HJ, Looney AJ, Miller WL. Closing the physician-staff divide: a step toward creating the medical home. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15(4):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruhe MC, Carter C, Litaker D, Stange KC. A systematic approach to practice assessment and quality improvement intervention tailoring. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(4):268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Litaker D, Ruhe M, Weyer S, Stange KC. Association of intervention outcomes with practice capacity for change: subgroup analysis from a group randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2008;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shea GP. Leading change. In: Rovin S, ed. Medicine and Business: Bridging the Gap. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2001: 33–52.

- 60.Litaker D, Ruhe M, Flocke S. Making sense of primary care practices’ capacity for change. Transl Res. 2008;152(5):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Argyris C, Schön D. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1995.

- 62.Lewin K. Frontiers in group dynamics. Hum Relat. 1947;1(1):5–41. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaén CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first National Demonstration Project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olson EE, Eoyang GH. Facilitating Organization Change: Lessons From Complexity Science. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Pfeiffer; 2001.

- 65.Jordan ME, Lanham HJ, Crabtree BF, et al. The role of conversation in health care interventions: enabling sensemaking and learning. Implement Sci. 2009;4:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perkins D. King Arthur’s Round Table: How Collaborative Conversations Create Smart Organizations. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003.

- 67.Crabtree BF. Primary care practices are full of surprises! Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28(3):279–283; discussion 289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF, Etz RS, et al. Fidelity versus flexibility: translating evidence-based research into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5 Suppl):S381–S389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bevan H, Robert G, Bate P, Maher L, Wells J. Using a design approach to assist large-scale organizational change: “10 high impact changes” to improve the national health service in England. J Appl Behav Sci. 2007;43(1):135–152. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Stange KC, Nutting PA, Jaén CR. A survivor‘s guide for primary care physicians. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):E1–E7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Solberg LI, Hroscikoski MC, Sperl-Hillen JM, Harper PG, Crabtree BF. Transforming medical care: case study of an exemplary, small medical group. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tallia AF, Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF. 7 characteristics of successful work relationships. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13(1):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller WL. Common space: creating a collaborative research conversation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Addison RB, Gilchrist VJ, Kuzel A, eds. Exploring Collaborative Research in Primary Care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994:265–288.

- 75.Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Stange KC. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2005;31(8):438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carter CA, Ruhe MC, Weyer SM, Litaker D, Fry RE, Stange KC. An appreciative inquiry approach to practice improvement and transformative change in health care settings. Qual Manag Health Care. 2007;16(3):194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cooperrider DL, Whitney D, Stavros JM. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2008.

- 78.Bohm D. On Dialogue. London, England: Routledge; 2000.

- 79.Patterson K, Grenny J, McMillan R, Switzler A, Covey SR. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When the Stakes Are High. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

- 80.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282(9):833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown J. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2005.

- 82.Weisbord MR, Janoff S. Future Search: An Action Guide to Finding Common Ground in Organizations and Communities. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 1995.

- 83.Tapping D, Tapping S, Williams J. The Lean Pocket Handbook for Kaizen Events: Any Industry—Any Time. Chelsea, MI: MCS Media, Inc; 2007.

- 84.Owen H. Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 1997.

- 85.Shields K. In the Tiger’s Mouth: An Empowerment Guide for Social Action. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers; 1994.

- 86.Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (I): technical competence, evidence-based medicine and relationship-centered care. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomas P, McDonnell J, McCulloch J, Ferlie E. Facilitating Learning and Innovation in Primary Care Organizations. London, UK: Brent NHS, Primary Care Trust; 2002:1–26.

- 88.Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

- 89.Stewart EE, Johnson BC. Huddles: improve office efficiency in mere minutes. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(6):27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuzel AJ. Ten steps to a patient-centered medical home. Fam Pract Manage. 2009;16(6):18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- 92.Miller S. Endangered species. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1171–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Jaén CR, Stewart EE. After the National Demonstration project: implications and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):s80–s90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation. Ann Fam Med. 2009; 7(2):100–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Healing landscapes: patients, relationships, and creating optimal healing places. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(Suppl1):S41–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]